Environmental impact of meat production

The environmental impact of meat production varies because of the wide variety of agricultural practices employed around the world. All agricultural practices have been found to have a variety of effects on the environment. Some of the environmental effects that have been associated with meat production are pollution through fossil fuel usage, animal methane, effluent waste, and water and land consumption. Meat is obtained through a variety of methods, including organic farming, free range farming, intensive livestock production, subsistence agriculture, hunting, and fishing.

Meat is considered one of the prime factors contributing to the current sixth mass extinction.[1][2][3][4][5] The 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services found that industrial agriculture and overfishing are the primary drivers of the extinction crisis, with the meat and dairy industries having a substantial impact.[6][7] The 2006 report Livestock's Long Shadow, released by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, states that "the livestock sector is a major stressor on many ecosystems and on the planet as a whole. Globally it is one of the largest sources of greenhouse gases (GHG) and one of the leading causal factors in the loss of biodiversity, and in developed and emerging countries it is perhaps the leading source of water pollution."[8] (In this and much other FAO usage, but not always elsewhere, poultry are included as "livestock".) A 2017 study published in the journal Carbon Balance and Management found animal agriculture's global methane emissions are 11% higher than previous estimates based on data from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.[9] Some fraction of these effects is assignable to non-meat components of the livestock sector such as the wool, egg and dairy industries, and to the livestock used for tillage. Livestock have been estimated to provide power for tillage of as much as half of the world's cropland.[10] A July 2018 study in Science asserts that meat consumption will increase as the result of human population growth and rising individual incomes, which will increase carbon emissions and further reduce biodiversity.[11]

On August 8, 2019, the IPCC released a summary of the 2019 special report which asserted that a shift towards plant-based diets would help to mitigate and adapt to climate change.[12] According to a 2018 study in the journal Nature, a significant reduction in meat consumption will be "essential" to mitigate climate change, especially as the human population increases by a projected 2.3 billion by the middle of the century.[13] In November 2017, 15,364 world scientists signed a Warning to Humanity calling for, among other things, drastically diminishing our per capita consumption of meat.[14] A similar shift to meat-free diets appears also as the only safe option to feed a growing population without further deforestation, and for different yields scenarios.[15]

| Categories | Contribution of farmed animal product [%] |

|---|---|

| Calories | 18 |

| Proteins | 37 |

| Land use | 83 |

| Greenhouse gases | 58 |

| Water pollution | 57 |

| Air pollution | 56 |

| Freshwater withdrawals | 33 |

Consumption and production trends

Changes in demand for meat may change the environmental impact of meat production by influencing how much meat is produced. It has been estimated that global meat consumption may double from 2000 to 2050, mostly as a consequence of increasing world population, but also partly because of increased per capita meat consumption (with much of the per capita consumption increase occurring in the developing world).[17] Global production and consumption of poultry meat have recently been growing at more than 5 percent annually.[17] According to an article written by Dave Roos "industrialized Western nations average more than 220 pounds of meat per person per year, while the poorest African nations average less than 22 pounds per person."[18] Trends vary among livestock sectors. For example, global per capita consumption of pork has increased recently (almost entirely due to changes in consumption within China), while global per capita consumption of ruminant meats has been declining.[17]

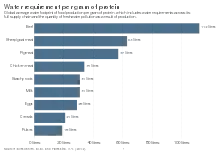

Grazing and land use

| Food Types | Land Use (m2year per 100g protein) |

|---|---|

| Lamb and mutton | 185 |

| Beef | 164 |

| Cheese | 41 |

| Pork | 11 |

| Poultry | 7.1 |

| Eggs | 5.7 |

| Farmed fish | 3.7 |

| Groundnuts | 3.5 |

| Peas | 3.4 |

| Tofu | 2.2 |

In comparison with grazing, intensive livestock production requires large quantities of harvested feed, this overproduction of feed can also hold negative effects. The growing of cereals for feed in turn requires substantial areas of land.

It takes seven pounds of feed to produce a pound of beef (live weight), more than three pounds for a pound of pork, and less than two pounds for a pound of chicken.[20] Assumptions about feed quality are implicit in such generalizations. For example, production of a pound of beef cattle live weight may require between 4 and 5 pounds of feed high in protein and metabolizable energy content, or more than 20 pounds of feed of much lower quality.[21]

About 85 percent of the world’s soybean crop is processed into meal and vegetable oil, and virtually all of that meal is used in animal feed.[22] Approximately six percent of soybeans are used directly as human food, mostly in Asia.[22] In the contiguous United States, 127.4 million acres of crops are grown for animal consumption, compared to the 77.3 million acres of crops grown for human consumption.[23]

Where grain is fed, less feed is required for meat production. This is due not only to the higher concentration of metabolizable energy in grain than in roughages, but also to the higher ratio of net energy of gain to net energy of maintenance where metabolizable energy intake is higher.[21]

Free-range animal production requires land for grazing, which in some places has led to land use change. According to FAO, "Ranching-induced deforestation is one of the main causes of loss of some unique plant and animal species in the tropical rainforests of Central and South America as well as carbon release in the atmosphere."[24]

Raising animals for human consumption accounts for approximately 40% of the total amount of agricultural output in industrialized countries. Grazing occupies 26% of the earth's ice-free terrestrial surface, and feed crop production uses about one third of all arable land.[8] More than one-third of U.S. land is used for pasture, making it the largest land-use type in the contiguous United States.[23]

Land quality decline is sometimes associated with overgrazing, as these animals are removing much needed nutrients from the soil without the land having time to recover. Rangeland health classification reflects soil and site stability, hydrologic function, and biotic integrity.[25] By the end of 2002, the US Bureau of Land Management (BLM) had evaluated rangeland health on 7,437 grazing allotments (i.e., 35 percent of its grazing allotments or 36 percent of the land area contained in its grazing allotments) and found that 16 percent of these failed to meet rangeland health standards due to existing grazing practices or levels of grazing use. This led the BLM to infer that a similar percentage would be obtained when such evaluations were completed.[26] Soil erosion associated with overgrazing is an important issue in many dry regions of the world.[8] On US farmland, much less soil erosion is associated with pastureland used for livestock grazing than with land used for production of crops. Sheet and rill erosion is within estimated soil loss tolerance on 95.1 percent, and wind erosion is within estimated soil loss tolerance on 99.4 percent of US pastureland inventoried by the US Natural Resources Conservation Service.[27]

Environmental effects of grazing can be positive or negative, depending on the quality of management,[28] and grazing can have different effects on different soils[29] and different plant communities.[30] Grazing can sometimes reduce, and other times increase, biodiversity of grassland ecosystems.[31][32] A study comparing virgin grasslands under some grazed and nongrazed management systems in the US indicated somewhat lower soil organic carbon but higher soil nitrogen content with grazing.[33] In contrast, at the High Plains Grasslands Research Station in Wyoming, the top 30 cm of soil contained more organic carbon as well as more nitrogen on grazed pastures than on grasslands where livestock were excluded.[34] Similarly, on previously eroded soil in the Piedmont region of the US, pasture establishment with well-managed grazing of livestock resulted in high rates of both carbon and nitrogen sequestration relative to results obtained where grass was grown without grazing.[35] Such increases in carbon and nitrogen sequestration can help mitigate greenhouse gas emission effects. In some cases, ecosystem productivity may be increased due to grazing effects on nutrient cycling.[36]

The livestock sector is also the primary driver of deforestation in the Amazon, with around 80% of all converted land being used to rear cattle.[37][38] 91% of land deforested since 1970 has been converted to cattle ranching.[39][40]

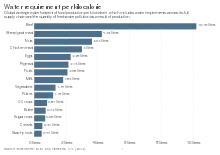

Water use

| Hoekstra & Hung (2003) | Chapagain & Hoekstra (2003) | Zimmer & Renault (2003) | Oki et al. (2003) | Average | |

| Beef | 15,977 | 13,500 | 20,700 | 16,730 | |

| Pork | 5,906 | 4,600 | 5,900 | 5,470 | |

| Cheese | 5,288 | 5,290 | |||

| Poultry | 2,828 | 4,100 | 4,500 | 3,810 | |

| Eggs | 4,657 | 2,700 | 3,200 | 3,520 | |

| Rice | 2,656 | 1,400 | 3,600 | 2,550 | |

| Soybeans | 2,300 | 2,750 | 2,500 | 2,520 | |

| Wheat | 1,150 | 1,160 | 2,000 | 1,440 | |

| Maize | 450 | 710 | 1,900 | 1,020 | |

| Milk | 865 | 790 | 560 | 740 | |

| Potatoes | 160 | 105 | 130 |

Almost one-third of the water used in the western United States goes to crops that feed cattle.[42] This is despite the claim that withdrawn surface water and groundwater used for crop irrigation in the US exceeds that for livestock by about a ratio of 60:1.[43] This excessive use of river water distresses ecosystems and communities, and drives scores of species of fish closer to extinction during times of drought.[44]

Irrigation accounts for about 37 percent of US withdrawn freshwater use, and groundwater provides about 42 percent of US irrigation water.[43] Irrigation water applied in production of livestock feed and forage has been estimated to account for about 9 percent of withdrawn freshwater use in the United States.[45] Groundwater depletion is a concern in some areas because of sustainability issues (and in some cases, land subsidence and/or saltwater intrusion).[46] A particularly important North American example where depletion is occurring involves the High Plains (Ogallala) Aquifer, which underlies about 174,000 square miles in parts of eight states, and supplies 30 percent of the groundwater withdrawn for irrigation in the US.[47] Some irrigated livestock feed production is not hydrologically sustainable in the long run because of aquifer depletion. Rainfed agriculture, which cannot deplete its water source, produces much of the livestock feed in North America. Corn (maize) is of particular interest, accounting for about 91.8 percent of the grain fed to US livestock and poultry in 2010.[48]:table 1–75 About 14 percent of US corn-for grain land is irrigated, accounting for about 17 percent of US corn-for-grain production, and about 13 percent of US irrigation water use,[49][50] but only about 40 percent of US corn grain is fed to US livestock and poultry.[48]:table 1–38

Effects on aquatic ecosystems

| Food Types | Eutrophying Emissions (g PO43-eq per 100g protein) |

|---|---|

| Beef | 301.4 |

| Farmed Fish | 235.1 |

| Farmed Crustaceans | 227.2 |

| Cheese | 98.4 |

| Lamb and Mutton | 97.1 |

| Pork | 76.4 |

| Poultry | 48.7 |

| Eggs | 21.8 |

| Groundnuts | 14.1 |

| Peas | 7.5 |

| Tofu | 6.2 |

In the Western United States, many stream and riparian habitats have been negatively affected by livestock grazing. This has resulted in increased phosphates, nitrates, decreased dissolved oxygen, increased temperature, turbidity, and eutrophication events, and reduced species diversity.[51][52] Livestock management options for riparian protection include salt and mineral placement, limiting seasonal access, use of alternative water sources, provision of "hardened" stream crossings, herding, and fencing.[53][54] In the Eastern United States, a 1997 study found that waste release from pork farms have also been shown to cause large-scale eutrophication of bodies of water, including the Mississippi River and Atlantic Ocean (Palmquist, et al., 1997). In North Carolina, where the study was done, measures have since been taken to reduce the risk of accidental discharges from manure lagoons; also, since then there is evidence of improved environmental management in US hog production.[55] Implementation of manure and wastewater management planning can help assure low risk of problematic discharge into aquatic systems.

Greenhouse gas emissions

| Food Types | Greenhouse Gas Emissions (g CO2-Ceq per g protein) |

|---|---|

| Ruminant Meat | 62 |

| Recirculating Aquaculture | 30 |

| Trawling Fishery | 26 |

| Non-recirculating Aquaculture | 12 |

| Pork | 10 |

| Poultry | 10 |

| Dairy | 9.1 |

| Non-trawling Fishery | 8.6 |

| Eggs | 6.8 |

| Starchy Roots | 1.7 |

| Wheat | 1.2 |

| Maize | 1.2 |

| Legumes | 0.25 |

At a global scale, the FAO has recently estimated that livestock (including poultry) accounts for about 14.5 percent of anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions estimated as 100-year CO2 equivalents.[57] A previous widely cited FAO report using somewhat more comprehensive analysis had estimated 18 percent.[8] Because this emission percentage includes contributions associated with livestock used for the production of draft power, eggs, wool and dairy products, the percentage attributable to meat production alone is significantly lower, as indicated by the report's data. The indirect effects contributing to the percentage include emissions associated with the production of feed consumed by livestock and carbon dioxide emission from deforestation in Central and South America, attributed to livestock production. Using a different sectoral assignment of emissions, the IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) has estimated that agriculture (including not only livestock, but also food crop, biofuel and other production) accounted for about 10 to 12 percent of global anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions (expressed as 100-year carbon dioxide equivalents) in 2005[58] and in 2010.[59]

A PNAS model showed that even if animals were completely removed from US agriculture, US GHG emissions would be decreased by 2.6% (or 28% of agricultural GHG emissions). The authors state this is because of the need to replace animal manures by fertilizers and to replace also other animal coproducts, and because livestock now use human-inedible food and fiber processing byproducts.[60] This study has been criticized,[61][62][63] and cannot be used to answer any question about what impact a dietary shift in the US (which imports a large portion of its animal products) would have globally, as it also does not take into account the effects that this change would have on meat production and deforestation in other countries.[60] One of this further study on the matter[61] has suggested that farmers would reduce their land use of feed crops; currently representing 75% of US land use, and would reduce the use of fertilizer due to the lower land areas and crop yields needed. A transition to a more plant based diet is also projected to improve health, which can lead to reductions in healthcare GHG emissions, currently standing at 8% of US emissions.[64]

In the US, methane emissions associated with ruminant livestock (6.6 Tg CH

4, or 164.5 Tg CO

2e in 2013)[65] are estimated to have declined by about 17 percent from 1980 through 2012.[66] Globally, enteric fermentation (mostly in ruminant livestock) accounts for about 27 percent of anthropogenic methane emissions,[67] and methane accounts for about 32 to 40 percent of agriculture's greenhouse gas emissions (estimated as 100-year carbon dioxide equivalents) as tabulated by the IPCC.[59] Methane has a global warming potential recently estimated as 35 times that of an equivalent mass of carbon dioxide.[67] The magnitude of methane emissions were recently about 330 to 350 Tg per year from all anthropogenic sources, and methane's current effect on global warming is quite small. This is because degradation of methane nearly keeps pace with emissions, resulting in a relatively little increase in atmospheric methane content (average of 6 Tg per year from 2000 through 2009), whereas atmospheric carbon dioxide content has been increasing greatly (average of nearly 15,000 Tg per year from 2000 through 2009).[67]

Mitigation options for reducing methane emission from ruminant enteric fermentation include genetic selection,[68][69] immunization, rumen defaunation, outcompetition of methanogenic archaea with acetogens,[70] introduction of methanotrophic bacteria into the rumen,[71][72] diet modification and grazing management, among others.[73][74][75] The principal mitigation strategies identified for reduction of agricultural nitrous oxide emission are avoiding over-application of nitrogen fertilizers and adopting suitable manure management practices.[76][77] Mitigation strategies for reducing carbon dioxide emissions in the livestock sector include adopting more efficient production practices to reduce agricultural pressure for deforestation (such as in Latin America), reducing fossil fuel consumption, and increasing carbon sequestration in soils.[57] A study conducted by Meat and Livestock Australia, CSIRO and James Cook University discovered that adding the seaweed Asparagopsis taxiformis to the cattle's diet can reduce methane by up to 99%, and reported a 3% seaweed diet resulted in an 80% reduction in methane.[78]

In New Zealand, nearly half of [anthropogenic] greenhouse gas emission is associated with agriculture, which plays a major role in the nation's economy, and a large fraction of this is assignable to the livestock industry.[79] Some fraction of this is assignable to meat production: FAO data indicate that meat accounted for about 7 percent of product tonnage from New Zealand's livestock (including poultry) in 2010.[66] Livestock sources (including enteric fermentation and manure) account for about 3.1 percent of US anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions expressed as carbon dioxide equivalents, according to US EPA figures compiled using UNFCCC methodologies.[80] Among sheep production systems, for example, there are very large differences in both energy use[81] and prolificacy;[82] both factors strongly influence emissions per kg of lamb production.

According to a 2018 study in the journal Nature, a significant reduction in meat consumption will be "essential" to mitigate climate change, especially as the human population increases by a projected 2.3 billion by the middle of the century.[13] A 2019 report in The Lancet recommended that global meat consumption be reduced by 50 percent to mitigate climate change.[83]

On August 8, 2019, the IPCC released a summary of the 2019 special report which said that a shift towards plant-based diets would help to mitigate and adapt to climate change.[84]

Effect of air pollution on human respiratory health

| Food Types | Acidifying Emissions (g SO2eq per 100g protein) |

|---|---|

| Beef | 343.6 |

| Cheese | 165.5 |

| Pork | 142.7 |

| Lamb and Mutton | 139.0 |

| Farmed Crustaceans | 133.1 |

| Poultry | 102.4 |

| Farmed Fish | 65.9 |

| Eggs | 53.7 |

| Groundnuts | 22.6 |

| Peas | 8.5 |

| Tofu | 6.7 |

Meat production is one of the leading causes of greenhouse gas emissions and other particulate matter pollution in the atmosphere. This type of production chain produces copious byproducts; endotoxin, hydrogen sulfide, ammonia, and particulate matter (PM), such as dust, are all released along with the aforementioned methane and CO

2.[85][86] Furthermore, elevated greenhouse gas emissions have been associated with respiratory diseases like asthma, bronchitis, and COPD, as well as increased chances of acquiring pneumonia from bacterial infections.[87]

In addition, exposure to PM10 (particulate matter 10 micrometers in diameter) may produce diseases that impact the upper and proximal airways.[88] Farmers aren’t the only ones at risk for exposure to these harmful byproducts. In fact, concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in proximity to residential areas adversely affect these individuals' respiratory health similarly seen in the farmers.[89] Concentrated hog feeding operations release air pollutants from confinement buildings, manure holding pits, and land application of waste. Air pollutants from these operations have caused acute physical symptoms, such as respiratory illnesses, wheezing, increased breath rate, and irritation of the eyes and nose.[90][91][92] That prolonged exposure to airborne animal particulate, such as swine dust, induces a large influx of inflammatory cells into the airways.[93] Those in close proximity to CAFOs could be exposed to elevated levels of these byproducts, which may lead to poor health and respiratory outcomes.

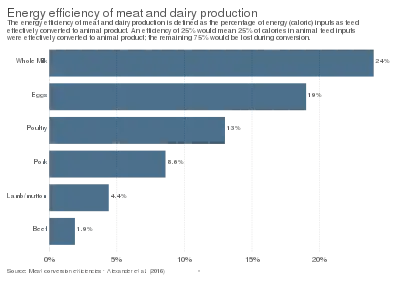

Energy consumption

Data of a USDA study indicate that about 0.9 percent of energy use in the United States is accounted for by raising food-producing livestock and poultry. In this context, energy use includes energy from fossil, nuclear, hydroelectric, biomass, geothermal, technological solar, and wind sources. (It excludes solar energy captured by photosynthesis, used in hay drying, etc.) The estimated energy use in agricultural production includes embodied energy in purchased inputs.[94]

An important aspect of energy use of livestock production is the energy consumption that the animals contribute. Feed Conversion Ratio is an animal's ability to convert feed into meat. The Feed Conversion Ratio (FCR) is calculated by taking the energy, protein, or mass input of the feed divided by the output of meat provided by the animal. A lower FCR corresponds with a smaller requirement of feed per meat out-put, therefore the animal contributes less GHG emissions. Chickens and pigs usually have a lower FCR compared to ruminants.[95]

Intensification and other changes in the livestock industries influence energy use, emissions, and other environmental effects of meat production. For example, in the US beef production system, practices prevailing in 2007 are estimated to have involved 8.6 percent less fossil fuel use, 16 percent less greenhouse gas emissions, 12 percent less water use and 33 percent less land use, per unit mass of beef produced, than in 1977.[96] These figures are based on an analysis taking into account feed production, feedlot practices, forage-based cow-calf operations, backgrounding before cattle enter a feedlot, and production of culled dairy cows.

Animal waste

Water pollution due to animal waste is a common problem in both developed and developing nations.[8] The USA, Canada, India, Greece, Switzerland and several other countries are experiencing major environmental degradation due to water pollution via animal waste.[97]:Table I-1 Concerns about such problems are particularly acute in the case of CAFOs (concentrated animal feeding operations). In the US, a permit for a CAFO requires the implementation of a plan for the management of manure nutrients, contaminants, wastewater, etc., as applicable, to meet requirements under the Clean Water Act.[98] There were about 19,000 CAFOs in the US as of 2008.[99] In fiscal 2014, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) concluded 26 enforcement actions for various violations by CAFOs.[100] Environmental performance of the US livestock industry can be compared with several other industries. The EPA has published 5-year and 1-year data for 32 industries on their ratios of enforcement orders to inspections, a measure of non-compliance with environmental regulations: principally, those under the Clean Water Act and Clean Air Act. For the livestock industry, inspections focused primarily on CAFOs. Of the 31 other industries, 4 (including crop production) had a better 5-year environmental record than the livestock industry, 2 had a similar record, and 25 had a worse record in this respect. For the most recent year of the five-year compilation, livestock production and dry cleaning had the best environmental records of the 32 industries, each with an enforcement order/inspection ratio of 0.01. For crop production, the ratio was 0.02. Of the 32 industries, oil and gas extraction and the livestock industry had the lowest percentages of facilities with violations.[101]

With good management, manure has environmental benefits. Manure deposited on pastures by grazing animals themselves is applied efficiently for maintaining soil fertility. Animal manures are also commonly collected from barns and concentrated feeding areas for efficient re-use of many nutrients in crop production, sometimes after composting. For many areas with high livestock density, manure application substantially replaces the application of synthetic fertilizers on surrounding cropland. Manure was spread as a fertilizer on about 15.8 million acres of US cropland in 2006.[102] Manure is also spread on forage-producing land that is grazed, rather than cropped. Altogether, in 2007, manure was applied on about 22.1 million acres in the United States.[50] Substitution of animal manure for synthetic fertilizer has important implications for energy use and greenhouse gas emissions, considering that between about 43 and 88 MJ (i.e. between about 10 and 21 Mcal) of fossil fuel energy are used per kg of N in the production of synthetic nitrogenous fertilizers.[103]

Manure can also have environmental benefits as a renewable energy source, in digester systems yielding biogas for heating and/or electricity generation. Manure biogas operations can be found in Asia, Europe,[104][105] North America, and elsewhere. The US EPA estimates that as of July 2010, 157 manure digester systems for biogas energy were in operation on commercial-scale US livestock facilities.[106] System cost is substantial, relative to US energy values, which may be a deterrent to more widespread use. Additional factors, such as odor control and carbon credits, may improve benefit to cost ratios.[107]

Effects on wildlife

Grazing (especially overgrazing) may detrimentally affect certain wildlife species, e.g. by altering cover and food supplies. The growing demand for meat is contributing to significant biodiversity loss as it is a significant driver of deforestation and habitat destruction; species-rich habitats, such as significant portions of the Amazon region, are being converted to agriculture for meat production.[110][1][111] World Resource Institute (WRI) website mentions that "30 percent of global forest cover has been cleared, while another 20 percent has been degraded. Most of the rest has been fragmented, leaving only about 15 percent intact."[112] WRI also states that around the world there is "an estimated 1.5 billion hectares (3.7 billion acres) of once-productive croplands and pasturelands—an area nearly the size of Russia—are degraded. Restoring productivity can improve food supplies, water security, and the ability to fight climate change."[113] The 2019 IPBES Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services also concurs that the meat industry plays a significant role in biodiversity loss.[114][115] Around 25% to nearly 40% of global land surface is being used for livestock farming.[114][116]

In North America, various studies have found that grazing sometimes improves habitat for elk,[117] blacktailed prairie dogs,[118] sage grouse,[119] and mule deer.[120][121] A survey of refuge managers on 123 National Wildlife Refuges in the US tallied 86 species of wildlife considered positively affected and 82 considered negatively affected by refuge cattle grazing or haying.[122] The kind of grazing system employed (e.g. rest-rotation, deferred grazing, HILF grazing) is often important in achieving grazing benefits for particular wildlife species.[123]

Effects on antibiotic resistance

Approximately 90% of the total use of antimicrobials in the United States was for non-therapeutic purposes in agricultural production.[124] Livestock production has been associated with increased antibiotic resistance in bacteria,[125] and has been associated with the emergence of microbes which are resistant to multiple antimicrobials (often referred to as superbugs).[126]

Beneficial environmental effects

One environmental benefit of meat production is the conversion of materials that might otherwise be wasted or turned into compost to produce food. A 2018 study found that, "Currently, 70 % of the feedstock used in the Dutch feed industry originates from the food processing industry."[127] Examples of grain-based waste conversion in the United States include feeding livestock the distillers grains (with solubles) remaining from ethanol production. For the marketing year 2009-2010, dried distillers grains used as livestock feed (and residual) in the US was estimated at 25.5 million metric tons.[128] Examples of waste roughages include straw from barley and wheat crops (edible especially to large-ruminant breeding stock when on maintenance diets),[21][129][130] and corn stover.[131][132] Also, small-ruminant flocks in North America (and elsewhere) are sometimes used on fields for removal of various crop residues inedible by humans, converting them to food.

Small ruminants can control of specific invasive or noxious weeds (such as spotted knapweed, tansy ragwort, leafy spurge, yellow starthistle, tall larkspur, etc.) on rangeland.[133] Small ruminants are also useful for vegetation management in forest plantations and for clearing brush on rights-of-way. These represent alternatives to herbicide use.[134]

See also

- Agroecology

- Animal-free agriculture

- Carbon dioxide equivalent tax

- Meat price

- Cultured meat

- Economic vegetarianism

- Factory farming divestment

- Semi-vegetarianism

- Environmental impact of agriculture

- Environmental impact of fishing

- Environmental impact of pig farming

- Environmental veganism

- Environmental vegetarianism

- Ethical eating

- Ethics of eating meat

- Farmageddon (book)

- Meat Atlas

- Food vs. feed

- Human impact on the environment

- Meatless Monday

- Meat tax

- Overpopulation

- Stranded assets in the agriculture and forestry sector

- Sustainable agriculture

- Sustainable diet

References

- Morell, Virginia (2015). "Meat-eaters may speed worldwide species extinction, study warns". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aad1607.

- Machovina, B.; Feeley, K. J.; Ripple, W. J. (2015). "Biodiversity conservation: The key is reducing meat consumption". Science of the Total Environment. 536: 419–431. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.536..419M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.022. PMID 26231772.

- Williams, Mark; Zalasiewicz, Jan; Haff, P. K.; Schwägerl, Christian; Barnosky, Anthony D.; Ellis, Erle C. (2015). "The Anthropocene Biosphere". The Anthropocene Review. 2 (3): 196–219. doi:10.1177/2053019615591020. S2CID 7771527.

- Smithers, Rebecca (5 October 2017). "Vast animal-feed crops to satisfy our meat needs are destroying planet". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- Woodyatt, Amy (May 26, 2020). "Human activity threatens billions of years of evolutionary history, researchers warn". CNN. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- McGrath, Matt (6 May 2019). "Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'". BBC. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

Pushing all this forward, though, are increased demands for food from a growing global population and specifically our growing appetite for meat and fish.

- Watts, Jonathan (6 May 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved 3 July 2019.

Agriculture and fishing are the primary causes of the deterioration. Food production has increased dramatically since the 1970s, which has helped feed a growing global population and generated jobs and economic growth. But this has come at a high cost. The meat industry has a particularly heavy impact. Grazing areas for cattle account for about 25% of the world’s ice-free land and more than 18% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

- Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, Tom; Castel, Vincent; Rosales, Mauricio; de Haan, Cees (2006), Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options (PDF), Rome: FAO

- Wolf, Julie; Asrar, Ghassem R.; West, Tristram O. (September 29, 2017). "Revised methane emissions factors and spatially distributed annual carbon fluxes for global livestock". Carbon Balance and Management. 12 (16): 16. doi:10.1186/s13021-017-0084-y. PMC 5620025. PMID 28959823.

- Bradford, E. (Task Force Chair). 1999. Animal agriculture and global food supply. Task Force Report No. 135. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology. 92 pp.

- Devlin, Hannah (July 19, 2018). "Rising global meat consumption 'will devastate environment'". The Guardian. Retrieved July 21, 2018.

- Schiermeier, Quirin (August 8, 2019). "Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet". Nature. Retrieved August 9, 2019.

- Carrington, Damian (October 10, 2018). "Huge reduction in meat-eating 'essential' to avoid climate breakdown". The Guardian. Retrieved October 16, 2017.

- Ripple WJ, Wolf C, Newsome TM, Galetti M, Alamgir M, Crist E, Mahmoud MI, Laurance WF (13 November 2017). "World Scientists' Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice". BioScience. 67 (12): 1026–1028. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix125.

- Erb KH, Lauk C, Kastner T, Mayer A, Theurl MC, Haberl H (19 April 2016). "Exploring the biophysical option space for feeding the world without deforestation". Nature Communications. 7: 11382. Bibcode:2016NatCo...711382E. doi:10.1038/ncomms11382. PMC 4838894. PMID 27092437.

- Damian Carrington, "Avoiding meat and dairy is ‘single biggest way’ to reduce your impact on Earth ", The Guardian, 31 May 2018 (page visited on 19 August 2018).

- FAO. 2006. World agriculture: towards 2030/2050. Prospects for food, nutrition, agriculture and major commodity groups. Interim report. Global Perspectives Unit, United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization. 71 pp.

- Roos, Dave. "The Juicy History of Humans Eating Meat". HISTORY. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Nemecek, T.; Poore, J. (2018-06-01). "Reducing food's environmental impacts through producers and consumers". Science. 360 (6392): 987–992. Bibcode:2018Sci...360..987P. doi:10.1126/science.aaq0216. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 29853680.

- Adler, Jerry; Lawler, Andrew (June 2012). "How the Chicken Conquered the World". Smithsonian. Retrieved April 19, 2015.

- National Research Council. 2000. Nutrient Requirements of Beef Cattle. National Academy Press.

- "Information About Soya, Soybeans". 2011-10-16. Archived from the original on 2011-10-16. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- Merrill, Dave; Leatherby, Lauren (2018-07-31). "Here's How America Uses Its Land". Bloomberg.com. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- "Cattle ranching is encroaching on forests in Latin America". Fao.org. 2005-06-08. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- National Research Council. 1994. Rangeland Health. New Methods to Classify, Inventory and Monitor Rangelands. Nat. Acad. Press. 182 pp.

- US BLM. 2004. Proposed Revisions to Grazing Regulations for the Public Lands. FES 04-39

- NRCS. 2009. Summary report 2007 national resources inventory. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service. 123 pp.

- Bilotta, G. S.; Brazier, R. E.; Haygarth, P. M. (2007). The impacts of grazing animals on the quality of soils, vegetation and surface waters in intensively managed grasslands. Adv. Agron. Advances in Agronomy. 94. pp. 237–280. doi:10.1016/s0065-2113(06)94006-1. ISBN 9780123741073.

- Greenwood, K. L.; McKenzie, B. M. (2001). "Grazing effects on soil physical properties and the consequences for pastures: a review". Austral. J. Exp. Agr. 41 (8): 1231–1250. doi:10.1071/EA00102.

- Milchunas, D. G.; Lauenroth, W. KI. (1993). "Quantitative effects of grazing on vegetation and soils over a global range of environments". Ecological Monographs. 63 (4): 327–366. doi:10.2307/2937150. JSTOR 2937150.

- Olff, H.; Ritchie, M. E. (1998). "Effects of herbivores on grassland plant diversity" (PDF). Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 13 (7): 261–265. doi:10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01364-0. PMID 21238294.

- Environment Canada. 2013. Amended recovery strategy for the Greater Sage-Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus urophasianus) in Canada. Species at Risk Act, Recovery Strategy Series. 57 pp.

- Bauer, A.; Cole, C. V.; Black, A. L. (1987). "Soil property comparisons in virgin grasslands between grazed and nongrazed management systems". Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 51 (1): 176–182. Bibcode:1987SSASJ..51..176B. doi:10.2136/sssaj1987.03615995005100010037x.

- Manley, J. T.; Schuman, G. E.; Reeder, J. D.; Hart, R. H. (1995). "Rangeland soil carbon and nitrogen responses to grazing". J. Soil Water Cons. 50: 294–298.

- Franzluebbers, A.J.; Stuedemann, J. A. (2010). "Surface soil changes during twelve years of pasture management in the southern Piedmont USA". Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 74 (6): 2131–2141. Bibcode:2010SSASJ..74.2131F. doi:10.2136/sssaj2010.0034.

- De Mazancourt, C.; Loreau, M.; Abbadie, L. (1998). "Grazing optimization and nutrient cycling: when do herbivores enhance plant production?". Ecology. 79 (7): 2242–2252. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[2242:goancw]2.0.co;2. S2CID 52234485.

- Wang, George C. (April 9, 2017). "Go vegan, save the planet". CNN. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- Liotta, Edoardo (August 23, 2019). "Feeling Sad About the Amazon Fires? Stop Eating Meat". Vice. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- Steinfeld, Henning; Gerber, Pierre; Wassenaar, T. D.; Castel, Vincent (2006). Livestock's Long Shadow: Environmental Issues and Options. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. ISBN 978-92-5-105571-7. Retrieved August 19, 2008.

- Margulis, Sergio (2004). Causes of Deforestation of the Brazilian Amazon (PDF). World Bank Working Paper No. 22. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. p. 9. ISBN 0-8213-5691-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2008. Retrieved September 4, 2008.

- "Virtual Water Trade" (PDF). Wasterfootprint.org. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- Richter, Brian D.; Bartak, Dominique; Caldwell, Peter; Davis, Kyle Frankel; Debaere, Peter; Hoekstra, Arjen Y.; Li, Tianshu; Marston, Landon; McManamay, Ryan; Mekonnen, Mesfin M.; Ruddell, Benjamin L. (2020-03-02). "Water scarcity and fish imperilment driven by beef production". Nature Sustainability. 3 (4): 319–328. doi:10.1038/s41893-020-0483-z. ISSN 2398-9629. S2CID 211730442.

- Kenny, J. F. et al. 2009. Estimated use of water in the United States in 2005, US Geological Survey Circular 1344. 52 pp.

- Borunda, Alejandra (March 2, 2020). "How beef eaters in cities are draining rivers in the American West". National Geographic. Retrieved April 27, 2020.

- Zering, K. D., T. J. Centner, D. Meyer, G. L. Newton, J. M. Sweeten and S. Woodruff.2012. Water and land issues associated with animal agriculture: a U.S. perspective. CAST Issue Paper No. 50. Council for Agricultural Science and Technology, Ames, Iowa. 24 pp.

- Konikow, L. W. 2013. Groundwater depletion in the United States (1900-2008). United States Geological Survey. Scientific Investigations Report 2013-5079. 63 pp.

- "HA 730-C High Plains aquifer. Ground Water Atlas of the United States. Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, Utah". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 2018-10-13.

- USDA. 2011. USDA Agricultural Statistics 2011.

- USDA 2010. 2007 Census of agriculture. AC07-SS-1. Farm and ranch irrigation survey (2008). Volume 3, Special Studies. Part 1. (Issued 2009, updated 2010.) 209 pp. + appendices. Tables 1 and 28.

- USDA. 2009. 2007 Census of Agriculture. United States Summary and State Data. Vol. 1. Geographic Area Series. Part 51. AC-07-A-51. 639 pp. + appendices. Table 1.

- Belsky, A. J.; et al. (1999). "Survey of livestock influences on stream and riparian ecosystems in the western United States". J. Soil Water Cons. 54: 419–431.

- Agouridis, C. T.; et al. (2005). "Livestock grazing management impact on streamwater quality: a review" (PDF). J. Am. Water Res. Assoc. 41 (3): 591–606. Bibcode:2005JAWRA..41..591A. doi:10.1111/j.1752-1688.2005.tb03757.x.

- "Pasture, Rangeland, and Grazing Operations - Best Management Practices | Agriculture | US EPA". Epa.gov. 2006-06-28. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- "Grazing management processes and strategies for riparian-wetland areas" (PDF). US Bureau of Land Management. 2006. p. 105.

- Key,N. et al. 2011. Trends and developments in hog manure management, 1998-2009. USDA EIB-81. 33 pp.

- Michael Clark; Tilman, David (November 2014). "Global diets link environmental sustainability and human health". Nature. 515 (7528): 518–522. Bibcode:2014Natur.515..518T. doi:10.1038/nature13959. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 25383533. S2CID 4453972.

- Gerber, P. J., H. Steinfeld, B. Henderson, A. Mottet, C. Opio, J. Dijkman, A. Falcucci and G. Tempio. 2013. Tackling climate change through livestock - a global assessment of emissions and mitigation opportunities. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. 115 pp.

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2007. Climate change 2007, Mitigation of climate change. Fourth Assessment Report

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014. Climate change 2014, Mitigation of climate change. Fifth Assessment Report.

- White, Robin R.; Hall, Mary Beth (Nov 13, 2017). "Nutritional and greenhouse gas impacts of removing animals from US agriculture". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 114 (48): E10301–E10308. doi:10.1073/pnas.1707322114. PMC 5715743. PMID 29133422.

- Van Meerbeek, Koenraad; Svenning, Jens-Christian (Feb 20, 2018). "Causing confusion in the debate about the transition toward a more plant-based diet". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (8): E1701–E1702. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720738115. PMC 5828628. PMID 29440444.

- Springmann, Marco; Clark, Michael; Willett, Walter (Feb 12, 2018). "Without animals, US farmers would reduce feed crop production". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (8): E1703. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720760115. PMC 5828630. PMID 29440446.

- Emery, Isaac (Feb 12, 2018). "Feedlot diet for Americans that results from a misspecified optimization algorithm". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (8): E1704–E1705. doi:10.1073/pnas.1721335115. PMC 5828635. PMID 29440445.

- Mariotti, François (2017). Vegetarian and Plant Based Diets in Health and Disease Prevention. ISBN 978-0-12-803968-7.

- US Environmental Protection Agency. 2015. Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks, 1990-2013. EPA 430-R-15-004.

- FAOSTAT. [Agricultural statistics database] Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome. http://faostat3.fao.org/

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2013. Climate change 2013, The physical science basis. Fifth Assessment Report.

- Bovine genomics project at Genome Canada

- Canada is using genetics to make cows less gassy

- Joblin, K. N. (1999). "Ruminal acetogens and their potential to lower ruminant methane emissions". Australian Journal of Agricultural Research. 50 (8): 1307. doi:10.1071/AR99004.

- The use of direct-fed microbials for mitigation of ruminant methane emissions: a review

- Parmar, N.R.; Nirmal Kumar, J.I.; Joshi, C.G. (2015). "Exploring diet-dependent shifts in methanogen and methanotroph diversity in the rumen of Mehsani buffalo by a metagenomics approach". Frontiers in Life Science. 8 (4): 371–378. doi:10.1080/21553769.2015.1063550. S2CID 89217740.

- Boadi, D (2004). "Mitigation strategies to reduce enteric methane emissions from dairy cows: Update review". Can. J. Anim. Sci. 84 (3): 319–335. doi:10.4141/a03-109.

- Martin, C. et al. 2010. Methane mitigation in ruminants: from microbe to the farm scale. Animal 4 : pp 351-365.

- Eckard, R. J.; et al. (2010). "Options for the abatement of methane and nitrous oxide from ruminant production: A review". Livestock Science. 130 (1–3): 47–56. doi:10.1016/j.livsci.2010.02.010.

- Dalal, R.C.; et al. (2003). "Nitrous oxide emission from Australian agricultural lands and mitigation options: a review". Australian Journal of Soil Research. 41 (2): 165–195. doi:10.1071/sr02064. S2CID 4498983.

- Klein, C. A. M.; Ledgard, S. F. (2005). "Nitrous oxide emissions from New Zealand agriculture – key sources and mitigation strategies". Nutrient Cycling in Agroecosystems. 72: 77–85. doi:10.1007/s10705-004-7357-z. S2CID 42756018.

- "Seaweed-fed cows could solve livestock industry's methane problems". 2017-04-21.

- Voluntary Greenhouse Gas Reporting Feasibility Study. 2. Agricultural sector GHG emissions in NZ. http://maxa.maf.govt.nz/climatechange/slm/vggr/page-01.htm

- US EPA. 2009. Inventory of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions and sinks: 1990-2007. United States Environmental Protection Agency. 410 pp.

- Gee, K. 1980. Cultural energy in sheep production. In: Handbook of Energy Utilization in Agriculture. CRC Press, Boca Raton. pp. 425-430

- USDA. 2010. Agricultural Statistics 2010, Table 7-43.

- Gibbens, Sarah (January 16, 2019). "Eating meat has 'dire' consequences for the planet, says report". National Geographic. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Schiermeier, Quirin (August 8, 2019). "Eat less meat: UN climate change report calls for change to human diet". Nature. Retrieved August 10, 2019.

- Merchant, James A.; Naleway, Allison L.; Svendsen, Erik R.; Kelly, Kevin M.; Burmeister, Leon F.; Stromquist, Ann M.; Taylor, Craig D.; Thorne, Peter S.; Reynolds, Stephen J.; Sanderson, Wayne T.; Chrischilles, Elizabeth A. (2005). "Asthma and Farm Exposures in a Cohort of Rural Iowa Children". Environmental Health Perspectives. 113 (3): 350–356. doi:10.1289/ehp.7240. PMC 1253764. PMID 15743727.

- Borrell, Brendan (December 3, 2018). "In California's Fertile Valley, a Bumper Crop of Air Pollution". Undark. Retrieved 2019-09-27.

- George, Maureen; Bruzzese, Jean-Marie; Matura, Lea Ann (2017). "Climate Change Effects on Respiratory Health: Implications for Nursing". Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 49 (6): 644–652. doi:10.1111/jnu.12330. PMID 28806469.

- Viegas, S.; Faísca, V. M.; Dias, H.; Clérigo, A.; Carolino, E.; Viegas, C. (2013). "Occupational Exposure to Poultry Dust and Effects on the Respiratory System in Workers". Journal of Toxicology and Environmental Health, Part A. 76 (4–5): 230–239. doi:10.1080/15287394.2013.757199. PMID 23514065. S2CID 22558834.

- Radon, Katja; Schulze, Anja; Ehrenstein, Vera; Van Strien, Rob T.; Praml, Georg; Nowak, Dennis (2007). "Environmental Exposure to Confined Animal Feeding Operations and Respiratory Health of Neighboring Residents". Epidemiology. 18 (3): 300–308. doi:10.1097/01.ede.0000259966.62137.84. PMID 17435437. S2CID 15905956.

- Schinasi, Leah; Horton, Rachel Avery; Guidry, Virginia T.; Wing, Steve; Marshall, Stephen W.; Morland, Kimberly B. (2011). "Air Pollution, Lung Function, and Physical Symptoms in Communities Near Concentrated Swine Feeding Operations". Epidemiology. 22 (2): 208–215. doi:10.1097/ede.0b013e3182093c8b. PMC 5800517. PMID 21228696.

- Mirabelli, M. C.; Wing, S.; Marshall, S. W.; Wilcosky, T. C. (2006). "Asthma Symptoms Among Adolescents Who Attend Public Schools That Are Located Near Confined Swine Feeding Operations". Pediatrics. 118 (1): e66–e75. doi:10.1542/peds.2005-2812. PMC 4517575. PMID 16818539.

- Pavilonis, Brian T.; Sanderson, Wayne T.; Merchant, James A. (2013). "Relative exposure to swine animal feeding operations and childhood asthma prevalence in an agricultural cohort". Environmental Research. 122: 74–80. Bibcode:2013ER....122...74P. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2012.12.008. PMC 3980580. PMID 23332647.

- Müller-Suur, C.; Larsson, K.; Malmberg, P.; Larsson, P.H. (1997). "Increased number of activated lymphocytes in human lung following swine dust inhalation". European Respiratory Journal. 10 (2): 376–380. doi:10.1183/09031936.97.10020376. PMID 9042635.

- Canning, P., A. Charles, S. Huang, K. R. Polenske, and A Waters. 2010. Energy use in the U.S. food system. USDA Economic Research Service, ERR-94. 33 pp.

- Röös, Elin; Sundberg, Cecilia; Tidåker, Pernilla; Strid, Ingrid; Hansson, Per-Anders (2013-01-01). "Can carbon footprint serve as an indicator of the environmental impact of meat production?". Ecological Indicators. 24: 573–581. doi:10.1016/j.ecolind.2012.08.004.

- Capper, J. L. (2011). "The environmental impact of beef production in the United States: 1977 compared with 2007". J. Animal Sci. 89 (12): 4249–4261. doi:10.2527/jas.2010-3784. PMID 21803973.

- "Livestock and the Environment".

- the US Code of Federal Regulations 40 CFR 122.42(e)

- United States Environmental Protection Agency. Appendix to EPA ICR 1989.06: Supporting Statement for the Information Collection Request for NPDES and ELG Regulatory Revisions for Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations (Final Rule)

- the US EPA. National Enforcement Initiative: Preventing animal waste from contaminating surface and groundwater. http://www2.epa.gov/enforcement/national-enforcement-initiative-preventing-animal-waste-contaminating-surface-and-ground#progress

- US EPA. 2000. Profile of the agricultural livestock production industry. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Office of Compliance. EPA/310-R-00-002. 156 pp.

- McDonald, J. M. et al. 2009. Manure use for fertilizer and for energy. Report to Congress. USDA, AP-037. 53pp.

- Shapouri, H. et al. 2002. The energy balance of corn ethanol: an update. USDA Agricultural Economic Report 814

- Erneubare Energien in Deutschland - Rückblick und Stand des Innovationsgeschehens. Bundesministerium fűr Umwelt, Naturschutz u. Reaktorsicherheit. http://www.bmu.de/files/pdfs/allgemin/application/pdf/ibee_gesamt_bf.pdf%5B%5D

- Biogas from manure and waste products - Swedish case studies. SBGF; SGC; Gasföreningen. 119 pp. http://www.iea-biogas.net/_download/public-task37/public-member/Swedish_report_08.pdf%5B%5D

- "U.S. Anaerobic Digester" (PDF). Agf.gov.bc.ca. 2014-06-02. Retrieved 2015-03-30.

- NRCS. 2007. An analysis of energy production costs from anaerobic digestion systems on U.S. livestock production facilities. US Natural Resources Conservation Service. Tech. Note 1. 33 pp.

- Damian Carrington, "Humans just 0.01% of all life but have destroyed 83% of wild mammals – study", The Guardian, 21 May 2018 (page visited on 19 August 2018).

- Baillie, Jonathan; Zhang, Ya-Ping (2018). "Space for nature". Science. 361 (6407): 1051. Bibcode:2018Sci...361.1051B. doi:10.1126/science.aau1397. PMID 30213888.

- Hance, Jeremy (October 20, 2015). "How humans are driving the sixth mass extinction". The Guardian. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- Machovina, B.; Feeley, K. J.; Ripple, W. J. (2015). "Biodiversity conservation: The key is reducing meat consumption". Science of the Total Environment. 536: 419–431. Bibcode:2015ScTEn.536..419M. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.07.022. PMID 26231772.

- "Forests". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Suite 800, 10 G. Street NE; Washington; Dc 20002; Fax +1729-7610, USA / Phone +1729-7600 / (2018-05-04). "Tackling Global Challenges". World Resources Institute. Retrieved 2020-01-24.

- Watts, Jonathan (May 6, 2019). "Human society under urgent threat from loss of Earth's natural life". The Guardian. Retrieved May 18, 2019.

- McGrath, Matt (May 6, 2019). "Nature crisis: Humans 'threaten 1m species with extinction'". BBC. Retrieved July 1, 2019.

- Sutter, John D. (December 12, 2016). "How to stop the sixth mass extinction". CNN. Retrieved January 10, 2017.

- Anderson, E. W.; Scherzinger, R. J. (1975). "Improving quality of winter forage for elk by cattle grazing". J. Range MGT. 25 (2): 120–125. doi:10.2307/3897442. hdl:10150/646985. JSTOR 3897442. S2CID 53006161.

- Knowles, C. J. (1986). "Some relationships of black-tailed prairie dogs to livestock grazing". Great Basin Naturalist. 46: 198–203.

- Neel. L.A. 1980. Sage Grouse Response to Grazing Management in Nevada. M.Sc. Thesis. Univ. of Nevada, Reno.

- Jensen, C. H.; et al. (1972). "Guidelines for grazing sheep on rangelands used by big game in winter". J. Range MGT. 25 (5): 346–352. doi:10.2307/3896543. hdl:10150/647438. JSTOR 3896543. S2CID 81449626.

- Smith, M. A.; et al. (1979). "Forage selection by mule deer on winter range grazed by sheep in spring". J. Range MGT. 32 (1): 40–45. doi:10.2307/3897382. hdl:10150/646509. JSTOR 3897382.

- Strassman, B. I. (1987). "Effects of cattle grazing and haying on wildlife conservation at National Wildlife Refuges in the United States" (PDF). Environmental MGT. 11 (1): 35–44. Bibcode:1987EnMan..11...35S. doi:10.1007/bf01867177. hdl:2027.42/48162. S2CID 55282106.

- Holechek, J. L.; et al. (1982). "Manipulation of grazing to improve or maintain wildlife habitat". Wildlife Soc. Bull. 10: 204–210.

- "Hogging It!: Estimates of Antimicrobial Abuse in Livestock". Union of Concerned Scientists. 2001.

- Mathew, A. G.; Cissell, R.; Liamthong, S. (2007). "Antibiotic resistance in bacteria associated with food animals: a United States perspective of livestock production". Foodborne Pathog Dis. 4 (2): 115–133. doi:10.1089/fpd.2006.0066. PMID 17600481. S2CID 17878232.

- "Apocalypse Pig: The Last Antibiotic Begins to Fail". 21 November 2015.

- Elferink, E. V.; et al. (2008). "Feeding livestock food residue and the consequences for the environmental impact of meat". J. Clean. Prod. 16 (12): 1227–1233. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2007.06.008.

- Hoffman, L. and A. Baker. 2010. Market issues and prospects for U.S. distillers' grains supply, use, and price relationships. USDA FDS-10k-01

- Anderson, D. C. (1978). "Use of cereal residues in beef cattle production systems". J. Anim. Sci. 46 (3): 849–861. doi:10.2527/jas1978.463849x.

- Males, J. R. (1987). "Optimizing the utilization of cereal crop residues for beef cattle". J. Anim. Sci. 65 (4): 1124–1130. doi:10.2527/jas1987.6541124x.

- Ward, J. K. (1978). "Utilization of corn and grain sorghum residues in beef cow forage systems". J. Anim. Sci. 46 (3): 831–840. doi:10.2527/jas1978.463831x.

- Klopfenstein, T.; et al. (1987). "Corn residues in beef production systems". J. Anim. Sci. 65 (4): 1139–1148. doi:10.2527/jas1987.6541139x.

- "Livestock Grazing Guidelines for Controlling Noxious weeds in the Western United States" (PDF). University of Nevada. Retrieved 24 April 2019.

- Launchbaugh, K. (ed.) 2006. Targeted Grazing: a natural approach to vegetation management and landscape enhancement. American Sheep Industry. 199 pp.

Further reading

- McMichael AJ, Powles JW, Butler CD, Uauy R (Sep 12, 2007). "Food, livestock production, energy, climate change, and health" (PDF). Lancet. 370 (9594): 1253–63. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61256-2. PMID 17868818. S2CID 9316230. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 3, 2010.

- Baroni L, Cenci L, Tettamanti M, Berati M (Feb 2007). "Evaluating the environmental impact of various dietary patterns combined with different food production systems" (PDF). Eur J Clin Nutr. 61 (2): 279–86. doi:10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602522. PMID 17035955. S2CID 16387344.

- Heitschmidt RK, Vermeire LT, Grings EE (2004). "Is rangeland agriculture sustainable?". Journal of Animal Science. 82 (E–Suppl): E138–146. doi:10.2527/2004.8213_supplE138x (inactive 2021-01-13). PMID 15471792.CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2021 (link)

- Animal Waste and Water Quality: EPA's Response to the Waterkeeper Alliance Court Decision on Regulation of CAFOs Congressional Research Service

- Rob Bailey, Antony Froggatt, Laura Wellesley (December 3, 2014). "Livestock – Climate Change's Forgotten Sector: Global Public Opinion on Meat and Dairy Consumption". Research Paper. Retrieved August 30, 2016.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Gabbatiss, Josh (18 July 2018). "Meat and dairy companies to surpass oil industry as world's biggest polluters, report finds". The Independent.

- Phillips, Dom; Wasley, Andrew; Heal, Alexandra (July 2, 2019). "Revealed: rampant deforestation of Amazon driven by global greed for meat". The Guardian.

- Christensen, Jen (July 17, 2019). "To help save the planet, cut back to a hamburger and a half per week". CNN.