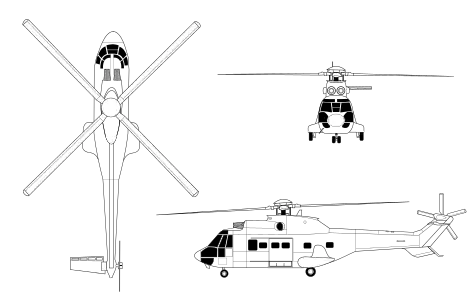

Eurocopter AS332 Super Puma

The Airbus Helicopters H215 (formerly Eurocopter AS332 Super Puma) is a four-bladed, twin-engine, medium-size utility helicopter developed and marketed originally by Aérospatiale, later by Eurocopter and currently by Airbus Helicopters. It is a re-engined and more voluminous version of the original Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma. First flying in 1978, the Super Puma succeeded the SA 330 Puma as the main production model of the type in 1980. Since 1990, Super Pumas in military service have been marketed under the AS532 Cougar designation. In civilian service, a next generation successor to the AS 332 was introduced in 2004, the further-enlarged Eurocopter EC225 Super Puma.

| AS332 Super Puma H215 | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| AS332M1 Super Puma of the Swiss Air Force | |

| Role | Medium utility helicopter |

| National origin | France |

| Manufacturer | Aérospatiale Eurocopter Airbus Helicopters |

| First flight | 13 September 1978 |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | French Air and Space Force CHC Helicopter Babcock Mission Critical Services Offshore Spanish Air Force |

| Produced | 1978–present |

| Number built | 1,000 (Sep 2019)[1] |

| Developed from | Aérospatiale SA 330 Puma |

| Variants | Eurocopter AS532 Cougar |

| Developed into | Eurocopter EC225 Super Puma |

Development

Origins

In 1974, Aérospatiale commenced development of a new medium transport helicopter based on its SA 330 Puma. The project was publicly announced at the 1975 Paris Air Show. While the new design maintained a similar generator layout to the preceding AS 330, it was powered by two of the new and more powerful Turbomeca Makila turboshaft engines, which drove a four-bladed main rotor which made use of composite materials. A great level of attention was paid to making the new model better withstand damage. A more robust fuselage structure was adopted along with a new crashworthy undercarriage, the rotor blades are also able to withstand a level of battle damage, as are the other key mechanical systems across the rotorcraft.[2]

External distinguishing features from the SA 330 include a ventral fin underneath the tail boom and a more streamlined nose.[3] From the onset, the new rotorcraft was planned to be available with two fuselage lengths; these were a short fuselage version that offered a similar capacity to the SA 330 while providing superior performance under "hot and high" conditions, and a stretched version which allowed for more internal cargo or passengers to be carried in circumstances where aircraft weight was less critical.[4]

A pre-production prototype, the SA 331, modified from a SA 330 airframe with Makila engines and a new gearbox flew on 5 September 1977.[5] The first prototype of the full Super Puma made its maiden flight on 13 September 1978, being followed by a further five prototypes.[6] Flight testing revealed that in comparison with the SA 330 Puma, the AS 330 Super Puma had a higher cruise speed and range, in part due to the Makila engine having a greater power output and a 17% reduction in fuel consumption per mile. The Super Puma also demonstrated far superior flight stabilisation tendencies and was less reliant on automated corrective systems.[7] The development of the military and civil variants was carried out in parallel, including the certification process.[8] In 1981 the first civil Super Puma was delivered.[9]

Production and improvements

In 1980, the AS 332 Super Puma had replaced the older SA 330 Puma as Aerospatiale's primary utility helicopter.[10] The AS 332 Super Puma proved to be highly popular. Between July 1981 and April 1987 there was an average production rate of three helicopters per month being built for customers, both military and civil.[11] Indonesian Aerospace (IPTN) has also manufactured both the SA 330 and AS 332 under license from Aerospatiale for domestic and some overseas customers.[12] By 2005 various models of Super Puma had been in operation with customers across 38 nations for a wide variety of purposes.[12] In total, 565 Super Pumas (including military-orientated Cougars) had been delivered or were on order at this point as well.[13]

The success of the AS 332 Super Puma led to the pursuit of extended development programs to produce further advanced models. Features included lengthened rotor blades, more powerful engines and gearboxes, increases in takeoff weight, and modernised avionics.[11] A wide variety of specialised Super Puma variants followed the basic transport model into use, including dedicated Search and rescue (SAR) and Anti-submarine warfare (ASW) versions. Military Super Pumas have been marketed as the AS532 Cougar since 1990. As a fallback option to the NHIndustries NH90, a Mark III Super Puma was also considered for development.[11]

In February 2012, Eurocopter offered a lower cost basic Super Puma configuration in order to better compete with the Russian-built Mil Mi-17.[14] Starlite Aviation became the launch customer for this new variant, designated AS 332 C1e.[15] In November 2015, Airbus Helicopters announced that manufacturing activity of the AS 332 Super Puma, which was redesignated as the H215 at that point, would be transferred to a new purpose-built final assembly facility in Brasov, Romania.[16] This move is aimed to cut production time and cost by simplifying production to a single baseline configuration that shall then be customised to meet the needs of both civil and military customers.[17]

Design

The AS332 Super Puma is powered by a pair of Turbomeca Makila 1A1 turboshaft engines which drive the rotorcraft's four-bladed main rotor and five-bladed tail rotor as well two separate hydraulic systems and a pair of electrical alternators. Fuel is housed in six internal fuel tanks, additional auxiliary and external tanks can be equipped for extended flight endurance. For safety, the fuel tanks use a crashworthy plumbing design and fire detection and suppression systems are installed in the engine bay. The monocoque tail boom is fitted with tail rotor strike protection, the forward portion of the boom accommodated a luggage compartment. The retractable tricycle landing gear is designed for high energy absorption qualities.[18]

The main cabin of the Super Puma, which is accessed via two sliding plug doors, used a reconfigurable floor arrangement, various passenger seating or cargo configurations can be adopted, including specialised configurations for medical operators. According to Airbus Helicopters, in addition to the two pilots, the short-fuselage AS332 can accommodate up to 15 passengers while the stretched-fuselage AS332 increases this to 20 passengers in a comfortable configuration.[19] Soundproof upholstery is installed, as is separately-adjustable heating and ventilation systems. Along with the doors, 12 windows around the main cabin area are jettisonable for emergency exits. The lower fuselage can also be fitted with flotation gear. A hatch in the floor to access the cargo sling pole is present in the cabin, as is individual stowage space for airborne equipment.[18]

The flight control system of the Super Puma uses a total of 4 dual-body servo units for pitch control of the cyclic, collective, and tail rotor. A duplex digital autopilot is also incorporated. The cockpit is equipped with dual flight controls. Principle instrumentation consists of four multifunction liquid crystal displays along with two display and autopilot control panels; for redundancy, a single Integrated Standby Instrument System (ISIS) and Vehicle Monitoring System (VMS) are also fitted.[18] According to Airbus Helicopters, the avionics installed upon later variants has ensured a high level of operational safety.[20] Third party firms have offered various upgrades for the Super Puma, these have included integrated flight management systems, global positioning systems (GPS) receivers, a digital map display, flight data recorders, an anti-collision warning system, Night Vision Goggles-compatibility, and multiple radios.[21][22][23]

A navalised variant of the Super Puma has also been manufactured for performing anti-submarine warfare and anti-surface warfare missions. In such a configuration, the Super Puma is modified with additional corrosion protection, a folding tail rotor boom, a deck-landing guidance system, sonar equipment, and the nose-mounted Omera search radar. For the anti-surface role, it can be armed with a pair of Exocet anti-ship missiles.[24]

Operational history

VH-34 is the Brazilian Air Force's designation for the helicopter used to transport the President of Brazil. Two modified Super Pumas were used as the main presidential helicopters, having been configured to carry up to fifteen passengers and three crew members. The VH-34 model was progressively supplemented and later replaced by the VH-36, the later EC725.[25][26] Various French presidents, such as François Mitterrand, have used military Super Pumas as an official transport during diplomatic missions.[27] In 2008, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown was flown in a Super Puma during a tour of Iraq.[28]

In August 1983, the French government created a new reactionary taskforce, the Force d'Action Rapide, to support France's allies as well as to contribute to France's overseas engagements in Africa and the Middle East; up to 30 Super Pumas were assigned to the taskforce.[29] In June 1994, France staged a military intervention in the ongoing Rwandan genocide, dispatching a military task force to neighboring Zaire; Super Pumas provided the bulk of the task force's rotary lift capability, transporting French troops and equipment during their advance into Rwanda.[30]

By 2015, 187 Super Pumas had been reportedly ordered by military customers; amongst others, the orders included 29 for Argentina, 30 for Spain, 33 for Indonesia, 22 for Singapore and 12 for Greece.[31]

During the 1980s, the French Army were interested in mounting an airborne battlefield surveillance radar upon the Super Puma. The first prototype Orchidée was assembled at Aerospatiale's Marignane factory and began testing in late 1988; the French Army intended to procure 20 aircraft to equip two squadrons. Orchidée was described as having a pulse-Doppler radar mounted on the fuselage's underside, being capable of 360-degree scanning to detect low flying helicopters and ground vehicles at ranges of up to 150 km; gathered data was to be relayed in real time to mobile ground stations via a single-channel data link for processing and analysis before being transmitted to battlefield commanders. The system was said to be capable of all-weather operation, and would feature protection against counteracting hostile electronic countermeasures.[32] However, development was aborted in mid-1990 during post-Cold War defence spending reductions.[33]

Various nations deployed Super Pumas to the Afghan theatre during the War in Afghanistan.[34][35] Between 2005 and 2011, Spanish Super Pumas were the sole type providing combat search and rescue (CSAR) and MEDEVAC cover in Afghanistan's western regions, the last of these were withdrawn in November 2013.[36]

In late 1990s, the Hellenic Air Force (HAF) issued a request for acquiring more modern and capable SAR helicopters [37] in order to replace its ageing fleet of Agusta Bell AB-205 SAR helicopters, which were in use since 1975. The need for an all-weather, day and night, long range SAR helicopter for operations throughout the Athens FIR came up after the Imia/Kardak incident of 1996, and the growing tension between Greece and Turkey over territorial water disputes on the Aegean Sea. The Greek government, signed a deal with Eurocopter in 1998 [38] for purchasing initially 4 AS-332 C1 Super Pumas.[39] H.A.F. acquired 2 more Super Pumas for air support operations of the Athens 2004 Olympic Games and 6 more helicopters followed up in the period 2007–2011 for the new CSAR role of the 384 SAR/CSAR Sq. All HAF helicopters are of the C1 version, including a 4-axis auto pilot, a NADIR type1000 navigation and mission management computer, FLIR turrets, an RBR1500B search radar, an engine anti-icing system, a hydraulic and an electrical hoist, a SPECTROLAB SX-16 searchlight, engine exhaust gas deflectors, a Bertin loudspeaker and 6 stretcher interior configuration for MEDEVAC missions.[40]

In 1990, Nigeria made a deal with Aerospatiale to exchange several of their Pumas for larger Super Pumas.[41] In November 2009, an additional five used Super Pumas were acquired from France for peacekeeping and surveillance operations in the Niger Delta.[42] In 2015, it was reported that a number of weaponised Super Pumas had been procured by the Nigerian Air Force for anti-insurgency operations against Boko Haram.[43]

The Super Puma has reportedly proven to be well-suited to off-shore operations for the North Sea oil industry, where the type has been used to ferry personnel and equipment to and from oil platforms. One of the biggest civil operators of the Super Puma is Bristow Helicopters, who had a fleet of at least 30 Super Pumas in 2005;[12] CHC Helicopters is another large civil operator, having possessed a fleet of 56 Super Pumas in 2014.[44] During the 1990s, Iran procured at least seven Indonesian-built Super Pumas for civil offshore oil exploration missions.[45][46]

In 2014, Airbus Helicopters, the manufacturer of the type, declared that the Super Puma/Cougar family had accumulated a total of 890 delivered rotorcraft to customers across 56 nations.[20]

In November 2017, Romania announced its intention to buy up to 16 aircraft, planning a down-payment of 30% towards the first four aircraft later that year.[47]

Variants

.jpg.webp)

- SA 331 – Initial prototype, based on SA 330 airframe, first flew on 5 September 1977.[6]

- AS 332A – Commercial pre-production version.

- AS 332B – Military version.

- AS 332B1 – First military version.

- AS 332C – Production civil version.[9]

- AS 332C1 – Search and rescue version, equipped with a search radar and six stretchers.[9]

- AS 332F – Military anti-submarine and anti-ship version.

- AS 332F1 – Naval version.

- AS 332L – Civil version with more powerful engines, a lengthened fuselage, a larger cabin space and a larger fuel tank.[9]

- AS 332L1 – Stretched civil version, with a long fuselage and an airline interior.[9]

- AS 332L2 Super Puma Mk 2 – Civil transport version, fitted with Spheriflex rotor head and EFIS.[9]

- AS 332M – Military version of the AS 332L.

- AS 332M1 – Stretched military version.

- NAS 332 – Licensed version built by IPTN, now Indonesian Aerospace (PT. Dirgantara Indonesia).

- VH-34 – Brazilian Air Force designation for the two VIP configured Super Pumas

Operators

Civilian

.jpg.webp)

- Serbian Police (3 on order)[58][59]

.jpg.webp)

Military

.jpg.webp)

- Ministry of Defense[66]

.jpg.webp)

Former operators

Notable accidents and incidents

- 16 July 1988 – an AS332 L operated by Helikopter Service AS ditched in the North Sea due to heavy vibrations caused by the loss of a metal strip from one of the main rotor blades. All passengers and crew survived.[79]

- 14 March 1992 – G-TIGH lost control and crashed into the North Sea near East Shetland Basin. 11 of the 17 passengers and crew died.[80]

- 19 January 1995 – G-TIGK operated by Bristow Helicopters ditched in the North Sea. There were no fatalities; the aircraft, however, was lost.

- 18 January 1996 – LN-OBP, an AS332 L1 operated by Helikopter Service AS, ditched in the North Sea some 200 kilometers south-west of Egersund. All passengers and crew survived and the helicopter was still floating 3 days later.[79]

- 18 March 1996 – LN-OMC, an AS332 operated by Airlift from Svalbard Airport crashed at Wijdefjorden. There were no fatalities

- 8 September 1997 – LN-OPG, an AS332 L1 operated by Helikopter Service AS, suffered a catastrophic main gearbox failure and crashed en route from Brønnøysund to the Norne oil field, killing all 12 aboard.[81] Eurocopter accepted some but not all of the AAIB/N recommendations.[82]

- 11 August 2000 - Kaskasapakte, Sweden. A Swedish Air Force AS332M1 (10404 / H94) crash into the mountainside during initial approach to perform hoisting operations during a mountain rescue mission. All 3 crewmembers are killed. The cause of the accident was not fully detirmned, but difficult visual conditions is believed to have caused the crew to lose judgement of distance to the mountain side. [83]

- 18 November 2003 - Rörö, Sweden. A Swedish Air Force AS332M1 (10409 / H99) crash into the sea during a night-time hoist exercise near Rörö in Gothenburg’s archipelago. The task was to conduct a number of hoist cycles to the rescue ship "Märta Collin". On approach the aircraft suddenly hit the water at high velocity, killing six crew members. Only one crew member, a conscript rescue swimmer, survived with minor injuries. The cause of the accident was not fully determined, but was believed to have been the result of incorrect flight attitude awareness in bad weather. "Aviation Safety Network".

- 21 November 2006 – A Eurocopter AS332 L2 search and rescue helicopter ditched in the North Sea. The aircraft was equipped with two automatic inflatable life rafts, but both failed to inflate. The Dutch Safety Board afterwards issued a warning.[84]

- 1 April 2009 – A Bond Offshore Helicopters AS332L2 with 16 people on board crashed into the North Sea 13 miles (21 km) off Crimond on the Aberdeenshire coast; there were no survivors.[85] The AAIB's initial report found that the crash was caused by a "catastrophic failure" in the aircraft's main rotor gearbox epicyclic module.[86]

- 11 November 2011 – XC-UHP AS332-L Super Puma of Mexico's General Coordination of the Presidential Air Transport Unit crashed in the Amecameca region south of Mexico City. Mexico's Secretary of the Interior Francisco Blake Mora died in this accident along with seven other crew and passengers.[87]

- 21 March 2013 – During a readiness exercise, a German Federal Police (Bundespolizei) Eurocopter EC155 collided with a Super Puma on the ground while landing in whiteout conditions in the Olympic Stadium in Berlin, Germany, destroying both aircraft, killing one of the pilots and injuring numerous bystanders. The whiteout was caused by snow on the ground being stirred up by the helicopter downdraft.[88]

- 23 August 2013 – A Super Puma L2 helicopter G-WNSB experienced a (so far unexplained) loss of air speed on a low approach and ditched into the North Sea two miles west of Sumburgh Airport at about 18:20 BST. The aircraft experienced a hard impact and overturned shortly after hitting the water. However, its armed flotation system deployed and the aircraft stayed afloat. Four passengers were killed, while both crew and a further 12 passengers were rescued, most with injuries. To date, the AAIB stated it was not caused by mechanical failure. A court has ordered the CV/FDR be released to the UK CAA for analysis on behalf of the Crown Office.[89][90][91][92]

- 28 September 2016 - Saint Gothard Pass region, Switzerland, A Swiss Air Force Super Puma struck a landline 50m after taking off, both pilots were killed and the loadmaster sustained undisclosed injuries but survived. The helicopter was a total loss as it burned out completely. After a lengthy investigation the pilots were found to not have been at fault.

Specifications (AS332 L1)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 1993–94[93]

General characteristics

- Crew: 2

- Capacity: 24 passengers plus attendant / 4,490 kg (9,899 lb)

- Length: 16.79 m (55 ft 1 in) fuselage

- 18.7 m (61 ft) rotor turning

- Height: 4.97 m (16 ft 4 in)

- Empty weight: 4,660 kg (10,274 lb)

- Max takeoff weight: 9,150 kg (20,172 lb)

- Powerplant: 2 × Turbomeca Makila 1A1 turboshaft, 1,376 kW (1,845 hp) each

- Main rotor diameter: 16.2 m (53 ft 2 in)

- Main rotor area: 206.12 m2 (2,218.7 sq ft)

- Blade section: root: NACA 13112; tip: NACA 13106[94]

Performance

- Cruise speed: 277 km/h (172 mph, 150 kn) max,

- 247 km/h (153 mph; 133 kn) econ.

- Never exceed speed: 327 km/h (203 mph, 177 kn)

- Range: 851 km (529 mi, 460 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 5,180 m (16,990 ft)

- Rate of climb: 7.4 m/s (1,460 ft/min)

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

Related lists

References

- Citations

- Dominic Perry (7 September 2019). "Airbus delivers 1,000th Super Puma helicopter". Flightglobal.

- Jackson 1984, pp. 7–10.

- Lake 2002, p.82.

- Jackson 1984, p. 11.

- Jackson 1984, p.10.

- Lake 2002, p. 85.

- Lambert 1979, pp. 437, 439.

- Lambert 1979, p. 437.

- Endres and Gething 2005, p. 272.

- McGowen 2005, p. 194.

- Sedbon, Gary. "Aerospatiale develops Super Puma II." Flight International, 18 April 1987. p. 12.

- McGowen 2005, p. 195.

- Endres and Gething 2005, p. 487.

- Pyadushkin, Maxim and Robert Wall. "Mil Mi-171, Super Puma To Do Battle." Aviation Week, 13 February 2012.

- Noyé, Régis. "Starlite: Launch Customer for the New AS 332 C1e Super Puma." Airbus Helicopters, May 2013.

- "Romania to host production of new, robust, and cost-effective H215 heavy helicopter." Airbus Helicopters, 17 November 2015.

- Perry, Dominic. "Airbus Helicopters to revive Romanian aircraft manufacturing." Flight International, 17 November 2015.

- "AS332 L1e Technical Data – 2015." Airbus Helicopters, 2015.

- "Civil Range." Airbus Helicopters, 2015.

- "AS332 C1e." Airbus Helicopters, 2014.

- Morris, John. "RUAG Aviation Shows Super Puma Upgrade." Aviation Week, 11 September 2012.

- Osborne, Tony. "Adding On Capabilities For Combat Helicopters In Europe." Aviation Week, 25 March 2013.

- "CHC's Heli-One Group Awarded Swedish Military Super Puma Upgrade Contract." CHC Helicopters, 30 March 2006.

- "Military Aircraft of the World." Flight International, 1 August 1987. p. 24.

- "VH-34 Super Puma." Archived 28 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Brazilian Air Force. Retrieved 26 January 2009.

- "Helicóptero de Dilma apresenta problema no motor." EPC, 2 November 2013.

- Ripley 2010, p. 11.

- Watt, Nicholas. "Brown sets out plan for UK pull-out from Iraq." The Guardian, 20 July 2008.

- Chipman 1985, pp. 19–20.

- Charbonneau 2008, pp. 140–141.

- ARG. "Eurocopter Puma / Cougar Medium Transport Helicopter - Military-Today.com". www.military-today.com.

- Sedbon, Gilbert. "France develops Battlefield Radar." Flight International, 18 June 1988. p. 17.

- "French end development of Orchidee radar." Aviation Week & Space Technology, 133(13), 24 September 1990. p. 22.

- "Swedish Helicopter Wing prepares for operations in Afghanistan ." Shephard Media, 12 June 2010.

- "Spanish helicopters attacked by Afghan insurgents during rescue mission." ABC News, 12 July 2008.

- Cherisey, Erwan de. "HELISAF: Spanish SAR in Afghanistan." Air Forces Monthly, February 2014. No. 311. pp. 36–40.

- airforce-technology.com

- Defence-aerospace.com, Dec. 21, 2000

- helis.com

- Force, Hellenic Air. "AS 332C1 Super Puma - Hellenic Air Force".

- African Defence Journal, Issues 113–124, 1990. p. 12.

- "Nigeria buys oil security, peacekeeping ’copters." Reuters, 26 November 2009.

- Ejiofor, Clement. "NAF Use Weaponised Helicopters Against Boko Haram." Naija, May 2015.

- "CHC Helicopter Fiscal 2014 Fourth Quarter." CHC Helicopter, 10 July 2014. p. 28.

- Hunter 2010, p. 138.

- "IPTN pushes Super Puma sales to Iran." Flight International, 16 November 1993.

- Adamowski, Jarosław (3 November 2017). "Romania to buy H215 helos from Airbus-IAR consortium". Defense News. Warsaw, Poland. Archived from the original on 4 November 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- Eurocopter Press Release – Azerbaijan Airlines Orders 6 Helicopters From Eurocopter Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- "Azerbaijan Airlines AS332". Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "A Satisfied Eurocopter Customer". eurocopter.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "German Federal Police order Frasca helicopter FTDs". helihub.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Eurocopter and COHC Sign Contract for Two AS 332 L1 Super Pumas". eurocopter.com. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "CHC Helicopters fleet". chc.ca. Archived from the original on 13 February 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "GFS fleet". Government of Hong Kong. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "World's Air Forces 2004 pg. 63". Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Japan Coast Guard to boost its fleet". aviationnews.eu. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Thompson, Paul Fire/Disaster Prevention J-HangarSpace Retrieved February 27, 2017

- Bozinovski, Igor (18 March 2019). "Serbia to acquire H215 helicopters". FlightGlobal. Belgrade. Archived from the original on 18 March 2019. Retrieved 18 March 2019.

- "Serbia and Airbus Helicopters expand partnership". Airbus (Press release). 26 June 2019. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- "Bond fleet". bondaviationgroup.com. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Bristow Helicopter Fleet". bristowgroup.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "CHC Scotia". chc.ca. Retrieved 24 August 2013.

- "Sheriff's New Super Puma Rescue Helicopters". lacounty.gov. Archived from the original on 5 October 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "World Air Forces 2019". Flightglobal Insight. 2019. Retrieved 5 January 2019.

- "Eurocopter will supply two more AS332 L1 Super Puma helicopters to the Finnish Border Guard". aviationnews.eu. Archived from the original on 11 March 2013. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- Kirtzkhalia, N. (7 September 2015). "Georgian President strongly against sale of Super Puma helicopters by Defence Ministry". Trend. Retrieved 22 June 2015.

- "Moroccan Royal Gendarmerie recognized". helihub.com. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "World's Air Forces 2004", Flight International, 166 (4960), p. 49, 16–22 November 2004, retrieved 12 March 2013 – via Flightglobal Archive

- "TJ-AAR aerospatiale AS332L Super Puma C/N 2119". Helis.com. 13 June 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- World's Air Forces 2004, 166, 16–22 November 2004, p. 51, retrieved 12 March 2013 – via Flightglobal Archive

- World's Air Forces 2004, 166, 16–22 November 2004, p. 52, retrieved 12 March 2013 – via Flightglobal Archive

- "aerospatiale AS332L Super Puma C/N 2108". Helis.com. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "World's Air Forces 2004", Flight International, 166 (4960), p. 68, 16–22 November 2004, retrieved 12 March 2013 – via Flightglobal Archive

- "Swedish military retires last Super Puma". helihub.com. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "World's Air Forces 2004", Flight International, 166 (4960), p. 89, 16–22 November 2004, retrieved 12 March 2013 – via Flightglobal Archive

- "AS332L2 Super Puma in Royal Thai Air Force". Helis.com. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "World's Air Forces 2004", Flight International, 166 (4960), p. 90, retrieved 12 March 2013 – via Flightglobal Archive

- "5V-TAH G-BWZX LN-OLE aerospatiale AS332L Super Puma C/N 2120". Helis.com. Retrieved 2 August 2016.

- "Helikotertragedien: Tidligere helikopterulykker i Nordsjøen" [The helicopter tragedy: Previous helicopter accidents in the North Sea] (in Norwegian). Dagbladet. 8 September 1997. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- "Report on the accident to AS 332L Super Puma, G-Tigh near in Comorant 'A' Platform, East Shetland Basin, on 14 March 1992" (PDF). Air Accidents Investigation Branch. 26 April 1993. Retrieved 13 July 2018.

- "Report on the air accident 8 September 1997 in the Norwegian Sea approx. 100 nm west north west of Brønnøysund, involving Eurocopter AS 332L1 Super Puma, LN-OPG, operated by Helikopter Service AS" (PDF). Air Accident Investigation Board, Norway. November 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- "Comments on the conclusion & recommendations on the draft of the final report." Archived 8 October 2006 at the Wayback Machine May 2001.

- "All you need to know about helicopters in Sweden - Nordic Rotors". www.nordicrotors.com. Retrieved 5 February 2021.

- "Emergency landing in sea, AS322L2 Search and rescue helicopter, North…". 22 February 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2013.

- "Call for grounding of helicopters." BBC News, 11 April 2009.

- "Initial Report – Super Puma accident" Archived 13 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine London: Air Accidents Investigation Branch, 10 April 2009.

- "Muere Blake Mora en desplome de helicóptero". Noticieros Televisa. 11 November 2011.

- "Wie es zu dem tödlichen Hubschrauber-Absturz kam." Berliner Morgenpost, 21 March 2013.

- "Shetland helicopter crash: four people confirmed dead by police". The Guardian. 23 August 2013.

- "Super Puma stuck on platform overnight amid safety fears" STV news, 13 September 2013.

- "Scottish Court Orders Release of Helicopter CVFDR".

- "Pilots 'failed to spot reduced air speed'". BBC News, 18 October 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- Lambert 1993, pp. 148–149.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- Bibliography

- Charbonneau, Bruno. France and the New Imperialism: Security Policy in Sub-Saharan Africa. Ashgate Publishing, 2008. ISBN 0-75469-078-4.

- Chipman, John. French Military Policy and African Security, Routledge, 1985. ISBN 1-13470-553-0.

- Endres, Günter G. and Michael J. Gething. Jane's Aircraft Recognition Guide. HarperCollins UK, 2005. ISBN 0-00718-332-1.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces Directory". Flight International, Vol. 182, No. 5370, 11–17 December 2012. pp. 40–64. ISSN 0015-3710.

- Hunter, Shireen. Iran's Foreign Policy in the Post-soviet Era: Resisting the New International Order. ABC-CLIO, 2010. ISBN 0-31338-194-1.

- Jackson, Paul. "Super Puma". Air International, January 1984, Vol. 26 No. 1. ISSN 0306-5634. pp. 7–12, 33–35.

- Lake, Jon. "Variant File: Super Puma and Cougar: AS 332, AS 532 and EC 725". International Air Power Journal, Volume 3, Winter 2001/2002. Norwalk, Ct, USA:AIRtime Publishing, 2002. ISSN 1473-9917, ISBN 1-880588-36-6. pp. 80–93.

- Lambert, Mark. "Super Puma: Cat with More Muscle." Flight International, 11 August 1979. pp. 437–439.

- Lambert, Mark (editor). Janes's All The World's Aircraft 1993–94. Coulsdon, UK:Jane's Data Division, 1993. ISBN 0-7106-1066-1.

- McGowen, Stanley S. Helicopters: An Illustrated History Of Their Impact. ABC-CLIO, 2005. ISBN 1-85109-468-7.

- Ripley, Tim. Conflict in the Balkans 1991–2000. Osprey Publishing, 2010. ISBN 1-84176-290-3.