Fort Norfolk (Norfolk, Virginia)

Fort Norfolk is a historic fort and national historic district located at Norfolk, Virginia. With the original buildings having been built between 1795 and 1809, the fort encloses 11 buildings: main gate, guardhouse, officers' quarters, powder magazine, and carpenter's shop. Fort Norfolk is the last remaining fortification of President George Washington's 18th century harbor defenses, later termed the first system of US fortifications. It has served as the district office for the U.S. Army Engineer District, Norfolk since 1923.[5]

| Fort Norfolk | |

|---|---|

Plan of Fort Norfolk in 1860 | |

| Type | Star fort |

| Site information | |

| Owner | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers |

| Open to the public | Yes |

Fort Norfolk | |

| |

| Location | 803 Front St., Norfolk, Virginia |

| Coordinates | 36°51′24″N 76°18′24″W |

| Area | 4 acres (1.6 ha) |

| Built | 1794[1] |

| NRHP reference No. | 76002225[2] |

| VLR No. | 122-0007 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | October 29, 1976 |

| Designated VLR | December 16, 1975[3] |

| Condition | intact and occupied |

| Site history | |

| Built | 1775 (temporary battery) 1794–1795 (earthwork fort) 1807–1809 (masonry fort) |

| Built by | United States Army Corps of Engineers |

| In use | 1795–present |

| Materials | Stone, brick, earth |

| Battles/wars | American Revolution War of 1812 American Civil War |

It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1976,[2] and became a Virginia Landmark in 2013.[3] Now it is preserved as a historic fort and is open to the public during the summer.[6]

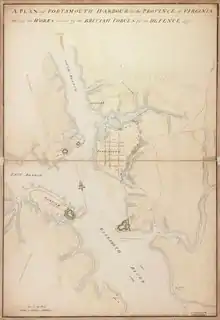

American Revolution

Although private property at the time, the site of Fort Norfolk was first fortified by citizens of Norfolk during the American Revolutionary War in order provide harbor defense.[5] The fort is located at a point where the Elizabeth River narrows and was used in conjunction with Fort Nelson on the opposite bank of the river in Portsmouth. This was done with the aim of providing a crossfire on any ships attempting to bombard and/or conduct an amphibious assault on Norfolk, Portsmouth, or the Gosport Navy Yard. Ultimately this failed as these positions were too weak to prevent a naval bombardment on Norfolk, later known as the Burning of Norfolk, by Lord Dunmore on January 1, 1776. At the time, Norfolk had been largely abandoned by its mostly pro-British Tory population. Patriot Whig forces made some effort to repel British landing parties, but did nothing to put out the fires and looted abandoned Tory properties.[7]

Construction

In 1794 Congress authorized President George Washington to build defensive fortifications along what they determined the "Maritime Frontier" in order to defend American harbors. This was later termed the first system of US fortifications.[8] By 1795, construction was largely complete on Fort Norfolk.[9] It was originally built with earthen walls and utilized either wooden or brick supports. The northern, eastern, and southern facing sides are designed after a Vauban style star fort. The western side resembles a half moon shape and is called a semicircular bastion.[10] This was an experimental design and the purpose was to maximize the number of cannon overlooking the river. While the design of a semicircular bastion is vulnerable to a land assault, this section of the fort is on the eastern bank of the Elizabeth River; therefore, it was not susceptible to a land assault. In 1797, records showed that Fort Norfolk had only a small caretaker garrison. In 1798 the fort was garrisoned with one company due to the start of the Quasi-War with France. In 1795 Captain Richard S. Blackburn's company was being formed, and by 1799 the company garrisoned both Fort Norfolk and Fort Nelson.[11]

War of 1812

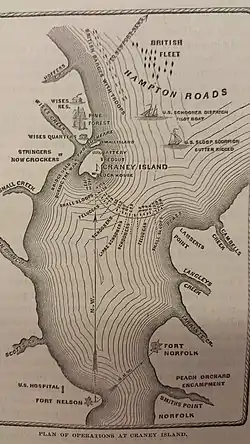

In 1807–1809 the fort was completely rebuilt with masonry, with a capacity of 30 guns and barracks for two companies, as part of the second system of US fortifications.[1][12][13] The defensive sea wall was reinforced to reach 12 feet high and 20 feet thick. The eastern and northern inland-facing sides continued to mimic a star fort. A ravelin was added on the east side of the fort to further reinforce the fort in preparation of a land assault. Additionally, this provided needed protection to the Officers' Quarters building, (used as the Shell House during the Civil War) which also served as the center part the eastern perimeter wall. The fort's armament included nine 18-pounder cannons with large quantities of gunpowder, shot, and shell. Although Fort Norfolk itself never saw conflict, it was in operation during the War of 1812. An elongated chain was stretched from Fort Norfolk to Fort Nelson in order to prevent the British Fleet from attacking Gosport Navy Yard, Norfolk, and/or Portsmouth. During the War of 1812, soldiers stationed at Fort Norfolk were sent to reinforce the defense at Craney Island and took part in the Battle of Craney Island.[5] Although the British were repulsed in that battle and did not enter Norfolk, they proceeded up Chesapeake Bay to burn Washington, D.C. and unsuccessfully attack Baltimore, as there were no forts guarding the mouth of the bay at the time.

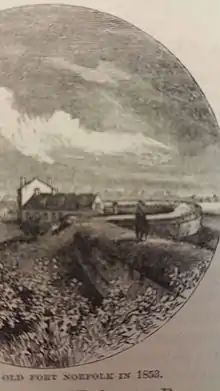

By the 1830s, the construction of Fort Monroe closed the entrance of Chesapeake Bay to potential enemies and made Fort Norfolk obsolete. Located outside of what were then the city limits, the fort remained standing but it was ungarrisoned. In 1853 local historian William S. Forrest described the fort as "long neglected, and is fast falling into ruins".[5]

Civil War

Prior to the American Civil War, in 1849–1856 a naval powder magazine was added and used to assemble, store, and load munitions for ships built or repaired at what was then the Gosport Navy Yard, now known as Norfolk Naval Shipyard.[14] Later, steps were taken to defend Norfolk from seceding armies. Fort Norfolk was again operational and a garrison company was assigned there.

When Virginia seceded in 1861, the Union Army was forced to abandon both Norfolk and Fort Norfolk. The Confederate Army occupied Norfolk and Portsmouth; therefore, occupying both the fort and the Gosport Shipyard. Fort Norfolk was then used by the Confederate Army to defend the shipyard. The fort's newly added powder magazine also supplied Confederate ships attempting to break the Union blockade on Hampton Roads. The most famous of these encounters was the Battle of Hampton Roads between the ironclads USS Monitor and CSS Virginia (often referred to as the Merrimac(k) because it was previously the USS Merrimack).

The Union Army reoccupied Fort Norfolk in May 1862 after General John E. Wool landed at Willoughby and marched on the city of Norfolk.[5] This caused the Confederates to evacuate both the fort and the city, resulting in Norfolk's surrender. For the remainder of the Civil War, under Union occupation, Fort Norfolk was used to imprison captured Confederate blockade runners.

Army Corps of Engineers

The Army Corps of Engineers occupied Fort Norfolk in 1923 and used the fort as offices to plan engineering works for the east coast.[5] During World War II, the fort continued to be used as offices for the Army Corps of Engineers, existing brick structures were renovated, and an additional structure for office use was built. In 1983, a new Army Corps of Engineers building was constructed next to Fort Norfolk, but they still retain offices in the fort. However, in collaboration with the Army Corps of Engineers, the Norfolk Historical Society began making restorations and giving tours of the fort in 1991.[6]

Timeline

- 1776 Commonwealth of Virginia establishes Fort Norfolk

- 1794 Congress authorizes President George Washington to construct a number of forts to protect U.S. harbors, including Fort Norfolk.

- 1810 Brick perimeter walls and most structures were built.

- 1813 22 June, Soldiers take part in the battle of Craney Island.

- 1834 Construction of Fort Monroe is completed and government abandons Fort Norfolk.

- 1850 U.S. Navy converts fort into ammunition depot.

- 1856 The large magazine is completed.

- 1861 Confederate General Taliaferro takes command of the fort and sets up a battery as the Civil War is declared.

- 1862 General Wool landed at Willoughby after the Confederate evacuation of Norfolk. Union army occupies Fort Norfolk and uses it as a federal prison.

- 1863 Returned to U.S. Navy for ammunition storage.

- 1880 Navy vacates the fort.

- 1921 Army Corps of Engineers occupies the fort.

- 1983 Army Corps of Engineers moves to new building.

- 1992 Fort Norfolk opens to the public.

(Dates for timeline found at Norfolk Historical Society, 1992 pamphlet on Fort Norfolk (archive link))

References

- Fort Norfolk at American Forts Network

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- "Virginia Landmarks Register". Virginia Department of Historic Resources. Retrieved 19 March 2013.

- Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 668.

- Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission Staff (December 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Fort Norfolk" (PDF). Virginia Department of Historic Resources. and Accompanying photo

- Fort Norfolk at U.S. Army Engineer District, Norfolk website

- Russell, David Lee (2000). The American Revolution in the Southern colonies. Jefferson, NC: McFarland. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-7864-0783-5. OCLC 248087936.

- Wade 2011, pp. 10–15, 59.

- Wade 2011, p. 28.

- Lewis, Emanuel Raymond (1979). Seacoast Fortifications of the United States. Annapolis: Leeward Publications. pp. 26, 28. ISBN 978-0-929521-11-4.

- Wade, Arthur P. (2011). Artillerists and Engineers: The Beginnings of American Seacoast Fortifications, 1794–1815. CDSG Press. pp. 28, 42, 45, 58. ISBN 978-0-9748167-2-2.

- Fort Norfolk at FortWiki.com

- Wade 2011, pp. 238, 245.

- Roberts, Robert B. (1988). Encyclopedia of Historic Forts: The Military, Pioneer, and Trading Posts of the United States. New York: Macmillan. p. 819. ISBN 0-02-926880-X.

External links

- Fort Norfolk at U.S. Army Engineer District, Norfolk website

- Norfolk Historical Society’s webpage on Fort Norfolk

- Norfolk Historical Society’s Virtual Tour

- Youtube link - Fort Norfolk, From Humble Beginnings

- Youtube link - French Influence On Forts Of The American Revolution

- American Forts Network, lists US, Canadian, some Latin American, and US overseas forts

- FortWiki, lists most US and Canadian forts