Founding fathers of the European Union

The founding fathers of the European Union are 11 men officially recognised as major contributors to European unity and the development of what is now the European Union. All but one (Winston Churchill from the United Kingdom) were from the Inner Six of the European Union.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of the European Union |

|

|

|

Sometimes emphasised are three pioneers of unification: Konrad Adenauer of Germany, Alcide De Gasperi of Italy and Robert Schuman of France.[1]

List

The European Union names 11 people[2] as its founding fathers.[3] These are:

| Picture | Name | Country | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

|

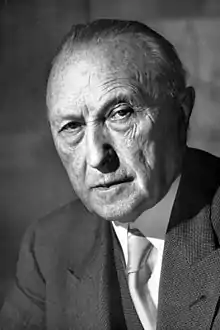

Konrad Adenauer | First chancellor of West Germany, Adenauer attempted to restore relations with France during his term in office between 1949 and 1963. He was instrumental in bringing about the 1963 Élysée Treaty between the two countries. He signed a treaty of friendship with France. | |

.jpg.webp) |

Joseph Bech | As Prime Minister of Luxembourg, Bech was actively involved in the establishment of the Benelux Customs Union and later the European Coal and Steel Community. Played an important role in preparing the 1955 Messina Conference which paved the way for the establishment of the European Economic Community in 1958. | |

.jpg.webp) |

Johan Beyen | Dutch foreign minister and one of the principal architects of the common market after 1955. | |

|

Winston Churchill | British prime minister during World War II, Churchill called for a "United States of Europe", organised democratically, to prevent future wars in Europe. He was a driving force behind the creation of the Council of Europe, a forerunner of the European Union. | |

|

Alcide De Gasperi | Italian prime minister and a skilled mediator, involved in the creation of the Council of Europe and in creating rapprochement between other European states. | |

|

Walter Hallstein | German academic and diplomat who served as the European Commission's first president at the European Economic Community and played a notable role in creating the common market | |

.jpg.webp) |

Sicco Mansholt | A farmer and member of the Dutch Resistance during World War II where he witnessed the Dutch famine of 1944, Mansholt's ideas on the need for European self-sufficiency in food formed the basis of the Common Agricultural Policy. | |

.jpg.webp) |

Jean Monnet | A political and economic advisor, Monnet helped to create the Schuman Declaration of 1950, a milestone Franco-German rapprochement after World War II and the creation of the European Coal and Steel Community, and promoted international industrial cooperation. | |

|

Robert Schuman | As French foreign minister between 1948 and 1952, Schuman was responsible for the 1950 Schuman Declaration (together with Jean Monnet) which agreed to place France and Germany's production of coal and steel under a single international authority, a key milestone towards the European Coal and Steel Community. | |

|

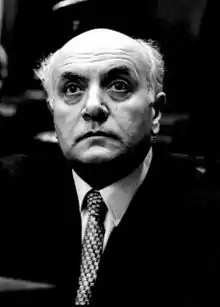

Paul-Henri Spaak | A Belgian prime minister involved in the negotiation of the Benelux Customs Union in 1944 and later appointed to leading roles in the United Nations, NATO, Council of Europe and European Coal and Steel Community in the 1950s and 1960s. He played an important role in creating the 1957 Treaty of Rome which led to the foundation of the European Economic Community. | |

|

Altiero Spinelli | A left-wing and progressivist politician and convinced federalist, Spinelli was involved in the Italian resistance during World War II and instrumental in the 1941 Ventotene Manifesto. He remained an influential federalist and was author of the 1984 Spinelli Plan, beginning a process which would culminate in the Maastricht Treaty and the creation of the European Union. |

Other sources discuss fewer names.[4]

Proposals and Rome

Count Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi (1894–1972) published the Paneuropa manifesto in 1923 which set up the movement of that name. At the start of the 1950s Robert Schuman (1886–1963), based on a plan by Jean Monnet (1888–1979), called for a European Coal and Steel Community in his "Schuman declaration". Monnet went on to become the first President of the High Authority. Schuman later served as President of the European Parliament and became notable for advancing European integration.[5]

Following its creation, the Treaty of Rome established the European Economic Community. Although not all the people who signed the treaty are known as founding fathers, a number are, such as Paul-Henri Spaak (1899–1972), who also worked on the treaty as well as the Benelux union and was the first President of the European Parliament.[5] Other founding fathers who signed the treaty were Konrad Adenauer (1876–1967) of Germany[6] and Joseph Bech (1887–1975) of Luxembourg.[7]

Others

Further men who have been considered founding fathers are: Giuseppe Mazzini (1805-1872) who founded the association "Young Europe" in 1834 with the vision of a united continent;[8] Victor Hugo (1802–1885) who made a speech where he called for United States of Europe in 1849 at the International Peace Congress of Paris; Milan Hodža (1878–1944) who was famous for his attempts to establish a democratic federation of Central European states (book: Federation in central Europe, reflections and reminiscences); Jacques Delors (born 1925), who was a successful Commission President in the 1980s and 90s; Lorenzo Natali (1922–1989); Carlo Azeglio Ciampi (1920-2016); Mário Soares (1924-2017), Portuguese Prime Minister at the time Portugal acceded the EC; and Pierre Werner (1913–2002) a Prime Minister of Luxembourg.[6]

Some have considered American Secretary of State George C. Marshall as an influential force in developing the European Union. His namesake plan to rebuild Europe in the wake of World War II contributed more than $100 billion in today's dollars to the Europeans, helping to feed Europeans, deliver steel to rebuild industries, provide coal to warm homes, and construct dams to help provide power. In doing so, the Marshall Plan encouraged the integration of European powers into the European Coal and Steel Community, the precursor to present-day European Union, by illustrating the effects of economic integration and the need for coordination. The potency of Marshall's plan caused German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt to remark that "[the] United States ought not to forget that the emerging European Union is one of its greatest achievements: it would never have happened without the Marshall Plan."[9]

See also

References

- Lala, R. M. (1 April 2011). In Search of Ethical Leadership. Vision Books. ISBN 9788170949695. Retrieved 17 June 2017 – via Google Books.

- European Commission Directorate-General for Communication, The European Union explained: The founding fathers of the EU, Brussels, 2013.

- "The Founding Fathers of the EU". European Union. Retrieved 2016-11-04.

- Smets, Paul F.; Ryckewaer, Mathieu, eds. (2001). Les pères de l'Europe: 50 ans après : perspectives sur l'engagement européen : actes du Colloque international des 19 et 20 mai 2000, Bruxelles, Palais d'Egmont Bibliothèque de la Fondation Paul-Henri Spaak [The Founding Fathers of Europe: 50 Years on: Perspectives on European Integration: Proceedings of the International Symposium on 19 and 20 May 2000, Brussels, Egmont Palace Library, Paul-Henri Spaak Foundation] (in French). with the support and cooperation of the Paul-Henri Spaak Foundation. Emile Bruylant. ISBN 9782802714439.

Bossuat, G. (2001). Les Fondateurs de l'Europe Unie [The Founders of European Unity] (in French). Belin. ISBN 978-270112962-4. - "Founding Fathers: Europeans Behind the Union - Europe - DW - 23.03.2007". DW.COM. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- "European Audio Visual Service - Founding Fathers". Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- Dumont, Patrick; Hirsh, Mario (2003). "Luxembourg". European Journal of Political Research. 42 (7–8): 1021. doi:10.1111/j.0304-4130.2003.00129.x.

- Mack Smith, Denis (1994). Mazzini. Yale University Press. pp. 11–12.

- "Europe: How The Marshall Plan Took Western Europe From Ruins To Union". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2019-06-20.