Budget of the European Union

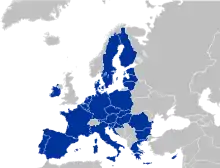

The European Union has a budget to finance policies carried out at European level (such as agriculture, regional development, space, trans-European networks, research and innovation, health, education and culture, migration, border protection and humanitarian aid).

| Submitted by | European Commission |

|---|---|

| Submitted to | Economic and Financial Affairs Council |

| Parliament | European Parliament |

| Total revenue | €148.2 billion |

| Total expenditures | €148.2 billion |

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the European Union |

|

|

The European Union budget is primarily an investment budget. Representing around 2% of all EU public spending, it aims to complement national budgets. Its purpose is to implement the priorities that all EU members have agreed upon. It provides European added-value by supporting actions which, in line with the principle of subsidiarity and proportionality, can be more effective than actions taken at national, regional or local level.

The EU has agreed on a budget of €165.8 billion for the year 2019,[1] representing around 1% of the EU-28's gross national income (GNI). The EU has a long-term budget of €1,082.5 billion for the period 2014–2020, representing 1.02% of the EU-28's GNI.[2] The long-term budget, also called the Multiannual Financial Framework, is a long-term spending plan, allowing the EU to plan and invest in long-term projects.

Initially, the EU budget used to fund mainly agriculture. In the 1980s and 1990s, Member States and the European Parliament broadened the scope of EU competences through changes in the Union's founding Treaties. Recognising the need to support the new single market, they increased the resources available under the Structural Funds to support economic, social and territorial cohesion. In parallel, the EU enhanced its role in areas such as transport, space, health, education and culture, consumer protection, environment, research, justice cooperation and foreign policy.

Since 2000, the EU budget has been adjusted to the arrival of 13 new Member States with diverse socioeconomic situations and by successive EU strategies to support jobs and growth and enhanced actions for the younger generation through the Youth Employment Initiative and Erasmus+. In 2015, it has set up the European Fund for Strategic Investments (EFSI), “so called Juncker plan” allowing to reinforce investments in the EU.

With regard to migration, it finances actions to provide emergency assistance to the frontline Member States, protect the external borders and contributes to reducing migratory pressures by directly assisting the countries and communities hosting refugees, as well as by addressing the root causes of migration in the wider regions of origin.

The EU budget finances the EU's external action, which seeks to promote democracy, peace, solidarity, stability and poverty reduction, by investing in its neighbourhood. It has also accompanied the growing role of the Union in the international arena, as a leader in the fight against climate change and as the largest donor of humanitarian and development aid in the world.[3]

The largest share of the EU budget (around 70% for the period 2014-2020) goes to agriculture and regional development. During the period 2014–2020, the share of EU spending on farming is set at 39%. In 1985, 70% was spent on farming. Farming's relatively large share of the EU budget is due to the fact that it is the only policy funded almost entirely from the common budget. This means that EU spending replaces national expenditure to a large extent.

The second share of EU spending goes to regional development (34% for the period 2014-2020). EU funding for regional and social development is an important source for key investment projects. In some EU countries that have otherwise limited means, European funding finances up to 80% of public investment.[4] However, EU regional spending does not just help poorer regions. It invests in every EU country, supporting the economy of the EU as a whole.

6% of the EU budget goes for the administration of all the European Institutions, including staff salaries, pensions, buildings, information technology, training programmes, translation, and the running of the European School system for the provision of education for the children of EU staff.

Adoption and management

Budget setting procedure

The EU budget is proposed annually by the European Commission. The proposed annual budget is then reviewed and negotiated by the Council of the European Union (which represents Member States' governments) and the European Parliament (which represents EU citizens). In order for the budget to be adopted, consensus of the majority of Member States is required and final endorsement by the European Parliament.[5]

The annual budget must remain within ceilings determined in advance by the Multiannual Financial Framework, laid down for a (five to) seven-year period. The Multiannual Financial Framework is a long-term spending plan, allowing the EU to plan and invest in long-term projects. It is proposed by the European Commission, and adopted by the council (requiring the unanimous approval of every Member State) with the assent of the European Parliament.

The budget for a year is determined in advance, but final calculations of payments required from each Member State are not completed until after the budget year is over, and information about the final revenue and expenditure is available, and correction mechanisms have been applied.

Audit and discharge

The commission is responsible for implementing the EU budget in cooperation with Member States in line with the principles of sound financial management, i.e. funds shall be spent in an effective, efficient and economic manner. A control framework has been set up to provide reasonable assurance that EU funds are paid in accordance with the relevant rules, and that measures are taken to prevent, detect and correct errors. In addition, a performance framework has been developed for the EU budget, increasing the focus on achieving results.

The Commission reports on how it has implemented the budget in various ways, most importantly by publishing the Integrated Financial Reporting Package, which consists of the annual accounts, the Annual Management and Performance Report, and other accountability reports.[6]

The annual discharge procedure allows the European Parliament and the council to hold the Commission politically accountable for the implementation of the EU budget. The European Parliament decides, after a recommendation by the council, on whether or not to provide its final approval, known as 'granting discharge', to the way the Commission implemented the EU budget in a given year. When granted, it leads to the formal closure of the accounts of the institution for a given year.

When deciding whether to grant, postpone or refuse the discharge, the Parliament takes into consideration the Integrated Financial Reporting Package prepared by the Commission along with the European Court of Auditors' Annual Report on how the budget has been spent and any relevant Special Reports from the Court. More particularly, every year the European Court of Auditors,[7] which is the European Union's independent external auditor, examines the reliability of accounts, whether all revenue has been received and all expenditure incurred in a lawful and regular manner, and whether the financial management has been sound.

The European Court of Auditors has signed off the European Union accounts every year since 2007. In October 2018, the European Court of Auditors gave the EU annual accounts a clean bill of health[8] for the 11th year in a row, finding them true and fair. The Court has given, for a second year in a row, a qualified opinion on the 2017 payments. The report thus shows further improvements in terms of compliance and performance, and confirms that the commission is on the right path. While a clean opinion means that the figures are true and fair, a qualified opinion means that there are minor issues still to be fixed. If Member States or final beneficiaries are found to spend EU money incorrectly, the Commission takes corrective measures. In 2017, the Commission recovered €2.8 billion, equal to 2.1% of the payments to the EU budget. Therefore, the actual amount at risk is below the 2% threshold, once corrections and recoveries have been taken into account.2% of any public budget is very high however hence the qualification.

Future long-term budget[9]

On 2 May 2018, the European Commission presented its proposal for 2021-2027 multiannual financial framework “A modern budget for a Union that protects, empowers and defends”[9] to the European Parliament, the council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions.

The Commission proposed to increase the funding for research, youth, climate action, migration and borders, security and external actions.

It calls for a modern, simple and flexible budget.

Modern: The Commission proposes to further cut red tape for beneficiaries and managing authorities by making rules more coherent on the basis of a single rulebook.

Simple: The structure of the budget will be clearer and more closely aligned with the Union's priorities. The Commission proposes to reduce the number of programmes by more than a third (from 58 currently to 37 in the future), bringing funding sources together and radically streamlining the use of financial instruments.

Flexible: The commission's proposal includes increased flexibility within and between programmes, to better manage crisis, tackle unforeseen events, and respond to emergencies in areas such as security and migration.

Revenue

Sources of income

Pie chart showing EU revenue sources (2017)[10]

The EU obtains its revenue from four main sources:

- Traditional own resources, comprising customs duties on imports from outside the EU and sugar levies;

- VAT-based resources, comprising a percentage (0.3% except Germany, Netherlands and Sweden that apply 0.15%) of Member State's standardised value added tax (VAT) base;

- GNI-based resources, comprising a percentage (around 0.7%) of each member state's gross national income (GNI); and

- Other revenue, including taxes from EU staff salaries, bank interest, fines and contributions from third countries.

Traditional own resources[10]

Traditional own resources are taxes raised on behalf of the EU as a whole, principally import duties on goods brought into the EU. These are collected by the Member States and passed on to the EU. Member States are allowed to keep a proportion of the duty to cover administration (20%). The European Commission operates a system of inspections to control the collection of these duties in Member States and thus ensure compliance with the European Union rules.

In 2017, the EU's revenue from customs duties was €20,325 million (14.6% of its total revenue). A production charge paid by sugar producers brought in revenue of €134 million. The total revenue from TORs (customs duties and sugar levies) was €20,459 million (14.7% of the EU's total revenue).

Countries are liable to make good any loss of revenue due to their own administrative failure.

VAT-based own resources[11]

The VAT-based own resource is a source of EU revenue based on the proportion of VAT levied in each member country. VAT rates and exemptions vary in different countries, so a formula is used to create the so-called “harmonised VAT base”, upon which the EU charge is levied. The starting point for calculations is the total VAT raised in a country. This is then adjusted using a weighted average rate of VAT rates applying in that country, producing the intermediate tax base. Further adjustments are made where there is a derogation from the VAT directive allowing certain goods to be exempt. The tax base is capped, such that it may not be greater than 50% of a Member State's gross national income (GNI). In 2017, eight Member States saw their VAT contribution reduced thanks to this 50% cap (Estonia, Croatia, Cyprus, Luxembourg, Malta, Poland, Portugal and Slovenia).

Member countries generally pay 0.3% of their harmonised VAT base into the budget, but there are some exceptions. The rate for Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden is 0.15% for the 2014-2020 period, while Austria also had a reduced rate in the 2007-2013 period.

The EU's total revenue from the VAT own resource was 16,947 million euros (12.2% of total revenue) in 2017.

Member States are required to send a statement of VAT revenues to the EU before July after the end of the budget year. The EU examines the submission for accuracy, including inspection visits by officials from the Directorate-General for Budget and Eurostat, who report back to the country concerned.

The country has a legal obligation to respond to any issues raised in the report, and discussions continue until both sides are satisfied, or the matter may be referred to the European Court of Justice for a final ruling. The Advisory Committee on Own Resources (ACOR), which has representatives from each Member State, gives its opinion where Member States have asked for authorisations to leave certain calculations out of account or to use approximate estimates. The ACOR also receives and discusses the inspection results. In 2018, 15 inspections were reported by inspectors to the ACOR. It is anticipated that 12 countries will be visited in 2019.

GNI-based own resources[10]

National contributions from the Member States are the largest source of the EU budget and are calculated based on gross national income. The Gross National Income (GNI)-based resource is an ‘additional’ resource that provides the revenue required to cover expenditure in excess of the amount financed by traditional own resources, VAT-based contributions and other revenue in any year.

The GNI-based resource ensures that the general budget of the Union is always initially balanced.

The GNI call rate is determined by the additional revenue needed to finance the budgeted expenditure not covered by the other resources (VAT-based payments, traditional own resources and other revenue). Thus a uniform call rate is applied to the GNI of each of the Member States.

Due to this covering mechanism the rate to be applied to the Member States’ gross national income varies from one financial year to another.

Nowadays this resource represents the largest source of revenue of the EU Budget (generally around 70% of the total financing). In 2017, due to the higher than usual other revenues and surplus from the previous year the rate of call of GNI was 0.5162548% and the total amount of the GNI resource levied was €78,620 million (representing 56.6% of total revenue). In 2017, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden benefited from an annual gross reduction in their GNI-based contribution (of respectively €130 million, €695 million and €185 million — all amounts are expressed in 2011 prices).

The total amount of own resources that may be collected for the EU Budget from Member States in any given year is limited with reference to Member States' GNI. Currently, the total amount of own resources allocated to the Union to cover annual appropriations for payments cannot exceed 1.20% of the sum of all the Member States' GNI.

The GNI for own resource purposes[12] is calculated by National Statistical Institutes according to European law governing the sources and methods to compile GNI and the transmission of GNI data and related methodological information to the commission (Eurostat). Basic information must be provided by the countries concerned to Eurostat before 22 September in the year following the budget year concerned.

Eurostat carries out information visits to the National Statistical Institutes forming part of the European Statistical System. Based on assessment reports by Eurostat, the Directorate-General for Budget of the Commission may notify to the Permanent Representative of the Member State concerned required corrections and improvements in the form of reservations on the Member State's GNI data. Payments are made monthly by Member States to the commission. Own resources payments are made monthly. Custom duties are made available by Member States after their collection. Payments of VAT- and GNI-based resources are based upon the budget estimates made for that year, subject to later correction.

Other revenue[10]

Other revenue accounted for 12.4% of EU revenue in 2017. This includes tax and other deductions from EU staff remunerations, contributions from non-EU countries to certain programmes (e.g. relating to research), interest on late payments and fines, and other diverse items.

As the balance from the previous year's budget is usually positive in comparison to the budget estimates, there is usually a surplus at the end of the year. This positive difference is returned to the Member States in the form of reduced contributions the following year.

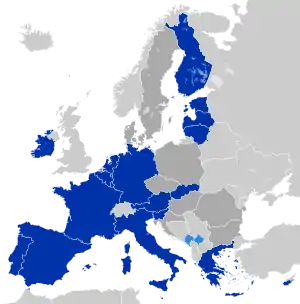

Correction mechanisms

The EU budget has a number of correction mechanisms designed to re-balance excessive contributions by certain member states:[13]

- The UK rebate, which reimburses the UK by 66% of the difference between its contributions to the budget and the expenditures received by the UK. This rebate is not paid to the UK, it is deducted from the amount the UK is due to pay. The effect of this rebate is to increase contributions required from all other member states, to make up the loss from the overall budget. Austria, Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden all have their contributions to make up for the UK rebate capped to 25% of their base contributions.

- Lump-sum payments to reduce annual GNI contributions for Austria, Denmark, the Netherlands and Sweden in the 2014-2020 budget (€60 million, €130 million, €695 million and €185 million respectively). (Austria's reduction expired in 2016.)

- A reduced VAT call rate of 0.15% (versus the regular rate of 0.30%) for Germany, the Netherlands and Sweden in the 2014-2020 budget.

The United Kingdom withdrawal from the European Union has led the EU to reconsider its funding mechanisms, with the rebates likely to change.[14] European Commissioner for Budget and Human Resources Günther Oettinger has stated that "I want to propose a budget framework that does not only do without the mother of all rebates [the U.K.’s] but without all of its children as well".[15]

Expenditure

Proportional outgoings

Approximately 94% of the EU budget funds programmes and projects both within member states and outside the EU.[16] Less than 7% of the budget is used for administrative costs, and less than 3% is spent on EU civil servants' salaries.[17]

2014–2020

2014 EU expenditure in millions of euros (total: 142,496 million)

For the period 2014–2020, the EU budget is used for six main categories of expenditure[18]

- Growth (aimed at enhancing competitiveness for growth and jobs and economic, social and territorial cohesion)

- Natural resources (covering the common agricultural and common fisheries policies, and rural and environmental measures)

- Security and citizenship (covering justice, border protection, immigration and asylum, public health, consumer protection and culture)

- Foreign policy (including development assistance or humanitarian aid outside the EU)

- Administration (covering all the European institutions, pensions and the European School system)

- Compensations (temporary payments to Croatia)

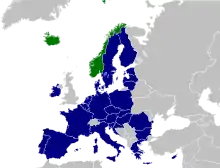

Funding by member states

Net receipts or contributions vary over time, and there are various ways of calculating net contributions to the EU budget, depending, for instance, on whether countries' administrative expenditure is included. Also, one can use either absolute figures, the proportion of gross national income (GNI), or per capita amounts. Different countries may tend to favour different methods, to present their country in a more favourable light.

EU-27 contributions (2007–13)

Note: in this budget period, "EU 27" meant the 27 member states prior to the accession of Croatia.

| Member state | Total national contributions[19] (€ millions) |

Share of total EU contributions[19] (%) |

Average net contributions[20] (€ millions) |

Average net contributions[20] (% of GNI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16,921 | 2.50 | 733 | 0.24 | |

| 22,949 | 3.16 | 1,303 | 0.35 | |

| 2,294 | 0.32 | -873 | -2.33 | |

| 1,077 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | |

| 8,995 | 1.24 | -1,931 | -1.32 | |

| 15,246 | 2.10 | 853 | 0.34 | |

| 1,001 | 0.14 | -515 | -3.3 | |

| 11,995 | 1.65 | 464 | 0.24 | |

| 128,839 | 17.76 | 5,914 | 0.29 | |

| 144,350 | 19.90 | 9,507 | 0.35 | |

| 14,454 | 1.99 | -4,706 | -2.23 | |

| 5,860 | 0.81 | -2,977 | -3.14 | |

| 9,205 | 1.27 | -474 | -0.32 | |

| 98,475 | 13.57 | 4,356 | 0.27 | |

| 1,323 | 0.18 | -651 | -3.07 | |

| 1,907 | 0.26 | -1,269 | -4.22 | |

| 1,900 | 0.26 | 75 | 0.28 | |

| 0,392 | 0.05 | -0,49 | -0.75 | |

| 27,397 | 3.78 | 2,073 | 0.33 | |

| 22,249 | 3.07 | -8,508 | -2.42 | |

| 10,812 | 1.49 | -3,196 | -1.89 | |

| 8,019 | 1.11 | -1,820 | -1.38 | |

| 4,016 | 0.55 | -1,040 | -1.56 | |

| 2,303 | 0.32 | -337 | -0.94 | |

| 66,343 | 9.15 | -3,114 | -0.29 | |

| 19,464 | 2.68 | 1,318 | 0.32 | |

| 77,655 | 10.70 | 4,872 | 0.25 |

EU-28 contributions (2014)

| Member state |

Member state contribution[22] (€ mil) |

Total member state contributions incl. TOR[23] (€ mil) |

Total EU expenditure in member state (€ mil) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3,660.2 | 5,232.7 | 7,044.3 | |

| 403.9 | 460.5 | 2,255.4 | |

| 1,308.8 | 1,506.7 | 4,377.2 | |

| 2,213.4 | 2,507.6 | 1,511.7 | |

| 25,815.9 | 29,143.0 | 11,484.5 | |

| 178.2 | 200.4 | 667.6 | |

| 1,425.1 | 1,650.6 | 1,563.1 | |

| 1,826.6 | 1,949.8 | 7,095.0 | |

| 9,978.1 | 11,111.0 | 11,538.5 | |

| 19,573.6 | 20,967.7 | 13,479.1 | |

| 387.2 | 429.8 | 584.3 | |

| 14,368.2 | 15,888.6 | 10,695.2 | |

| 142.8 | 160.6 | 272.9 | |

| 244.1 | 270.0 | 1,062.2 | |

| 320.4 | 384.7 | 1,885.9 | |

| 232.1 | 246.2 | 1,713.9 | |

| 890.3 | 995.8 | 6,620.2 | |

| 65.7 | 76.1 | 254.9 | |

| 6,391.0 | 8,372.7 | 2,014.4 | |

| 2,690.9 | 2,869.5 | 1,572.6 | |

| 3,526.5 | 3,954.6 | 17,436.1 | |

| 1,636.9 | 1,747.9 | 4,943.0 | |

| 1,353.1 | 1,458.9 | 5,943.9 | |

| 326.8 | 385.0 | 1,142.5 | |

| 625.1 | 720.2 | 1,668.8 | |

| 1,777.2 | 1,904.1 | 1,061.9 | |

| 3,828.2 | 4,294.3 | 1,691.0 | |

| 11,341.6 | 14,072.3 | 6,984.7 |

See also

References

- The EU Budget for 2019: growth, solidarity and security in Europe and beyond - provisional agreement reached. European Commission press release. 5 December 2018. https://europa.eu/!bX78Ht

- © European Union, Integrated Financial Reporting Package Overview, Financial year 2017. 2018. https://europa.eu/!hK34QQ

- © European Union, Reflection paper on the future of EU finances, 2017. https://europa.eu/!XF36Tq

- https://cohesiondata.ec.europa.eu/Other/-of-cohesion-policy-funding-in-public-investment-p/7bw6-2dw3

- How is the EU budget prepared? European Commission website. https://europa.eu/!mR67Gv

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/about-european-commission/eu-budget/library/publications/integrated-financial-reporting-package_en

- https://www.eca.europa.eu/en/Pages/ecadefault.aspx

- http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_IP-18-5984_en.htm

- EU budget for the future, European Commission website, https://europa.eu/!tk76Vk

- © European Union, Revenue section, EU Budget 2017 Financial Report, 2018. https://europa.eu/!hy73fY

- © European Union, Revenue section, EU Budget 2017 Financial Report, 2018. https://europa.eu/!hy73fY https://europa.eu/!hy73fY

- "Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- "The EU's own resources". Europa. European Commission. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "Brexit Fallout Could End Rebates for All EU States, Denmark Says". Bloomberg. 20 September 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- DELCKER, JANOSCH (6 January 2017). "Oettinger wants to scrap all rebates in post-Brexit EU budget". Retrieved 24 September 2017.

- "FAQ 6. Where does the money go?". Europa. Europa. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "FAQ 7. How much goes on administration?". Europa. Europa. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/financial-framework-proposed-european-commission_en

- Cipriani, Gabriele (2014). Financing the EU Budget (PDF). Centre for European Policy Studies. ISBN 978-1-78348-330-3. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "EU expenditure and revenue 2007-2013". Europa. European Commission. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- http://ec.europa.eu/budget/library/biblio/documents/2014/Internet%20tables%202000-2014.xls

- VAT own contributions plus GNI own contributions minus (UK rebate; lump sum payments to Netherlands and Sweden; JHA adjustment for Denmark, Ireland, UK). See citation 29 for breakdown

- See 'traditional own resources'

External links

- OpenSpending Project's "Where Does the EU's Money Go? – A Guide to the Data"

- Multi-annual Financial Framework 2014–2020 EU Commission website on the long-term budget proposals

- The European Parliament's Budget Focus Information about the 2011 Budget

- European Commission > Financial Programming and Budget

- Interview with EP Budget discharge rapporteur, European Parliament website (12 November 2008)

- Europe plans vast contingency fund, racing to contain crisis

- Iain Begg: An EU Tax: Overdue Reform or Federalist Fantasy?, Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, February 2011, PDF 140 KB