Garibaldi Provincial Park

Garibaldi Provincial Park, also called Garibaldi Park, is a wilderness park located on the coastal mainland of British Columbia, Canada, located 70 kilometres (43.5 mi) north of Vancouver. It was established in 1920 and named a Class A Provincial Park of British Columbia in 1927. The park is a popular destination for outdoor recreation, with over 30,000 overnight campers and over 106,000 day users in the 2017/2018 season.[2]

| Garibaldi Provincial Park | |

|---|---|

IUCN category II (national park)[1] | |

Garibaldi Lake and the Battleship Islands | |

_location_map.svg.png.webp) | |

| Location | British Columbia, Canada |

| Nearest city | Squamish & Whistler, British Columbia |

| Coordinates | 49°55′N 122°45′W |

| Area | 1,950 km2 (750 sq mi) |

| Established | April 29, 1920 |

| Governing body | BC Parks |

Garibaldi Park spans an area of over 1,950 square kilometres (753 sq mi), encompassing a majority of the Garibaldi Range mountains. The western side of the park is highly trafficked by the public due to the nearby Sea to Sky Highway providing access to destinations such as Elfin Lakes, Garibaldi Lake, The Black Tusk, Cheakamus Lake, and Wedgemount Lake. The eastern wilderness of the park is harder to access and therefore much more remote than its western counterpart. To the south, Garibaldi Park connects with Golden Ears Provincial Park and Pinecone Burke Provincial Park, while its northern sections stretch past Whistler and end just south of the village of Pemberton.

History

Indigenous people

Prior to the arrival of Europeans in the area, Mount Garibaldi was referred to by the Squamish people as Nch'kay, meaning "Dirty Place" or "Grimy One" in reference to the muddy water of the Cheekye River.[3] The mountain was an important cultural landmark for the Squamish, with its surrounding area being used for hunting, foraging, and the collection of obsidian.[4] In Squamish mythology, Nch'kay was the peak to which the people tied their canoes to avoid being swept away by the Great Flood.[3]

Another culturally significant peak within the park is The Black Tusk, which was known to the Squamish people as t'ak't'ak mu'yin tl'a in7in'a'xe7en. The name translates to "Landing Place of the Thunderbird", as the peak was said to have been crushed into its present shape by the talons of the in7in'a'xe7en, or Thunderbird. To the Lil'wat people, the same peak was known as Q'elqámtensa ti Skenknápa, or "Place Where the Thunder Rests".[5]

.jpg.webp)

Later history

Garibaldi Provincial Park received its modern name from Mount Garibaldi, which was itself named after Giuseppe Garibaldi by Captain George Henry Richards during a survey of Howe Sound in 1860.[6]

In 1907, the first ascent of Mount Garibaldi was completed by Vancouver mountaineers A. Dalton, W. Dalton, A. King, T. Pattison, J. J. Trorey, and G. Warren. The views from the peaks inspired the establishment of summer climbing camps at Garibaldi Lake, which included among their ranks many members of the newly-formed British Columbia Mountaineering Club.[7] The first of these camps resulted in the naming and first ascent of The Black Tusk, by a party led by William J. Gray in 1912.[5] The interest sparked by the camps eventually led to the park being legislated as a park reserve in 1920, and designated as a Class A Provincial park in 1927.[6]

In 1967, the southern section of Garibaldi Provincial park was split off as Golden Ears Provincial Park, which juts southward between the basins of Pitt Lake and the Stave River into the Municipality of Maple Ridge.[8]

Geology

Geological features

The park's landscape consists of many steep rugged mountains, coastal forests, and alpine lakes. Much of this landscape was shaped by quaternary continental and alpine glaciation, as well as volcanic activity such as the eruption of Mount Garibaldi some 13,000 years ago.[9]

.jpg.webp)

There are over 150 glaciers in the park, including the Garibaldi Névé and Mamquam icefields.[10] The highest peak in Garibaldi Park is Wedge Mountain, at an elevation of 2,891 metres (9,485 ft).[11] It also includes volcanic features such as an andesite tuya known as The Table, a cinder cone known as the Opal Cone, and the stratovolcanoes Mount Garibaldi and The Black Tusk, which are part of the Garibaldi Volcanic Belt.

There are a number of alpine lakes in the park, including Garibaldi Lake, Cheakamus Lake, Mamquam Lake, Elfin Lakes, and many other smaller lakes. The park is also the origin of the Pitt River, a tributary of the Fraser River.[12]

The Barrier

Garibaldi Lake is retained by a lava dam known as The Barrier. Sometime in the fall or winter of 1855–56, part of this dam gave away, which resulted in a 25,000,000 cubic meter landslide that devastated the area below.[13] The instability of the barrier was brought to public attention in the 1970s, eventually leading to the area below The Barrier being declared unsafe for habitation in 1981. The village of Garibaldi was evacuated as a result of this.

Today, the land immediately below The Barrier is referred to as the Barrier Civil Defence Zone by BC Parks. The area around it is denoted by signage warning hikers not to camp, stop, or linger within the hazard zone.[14]

Glacial recession

In 2007, a study on glacial recession in Garibaldi Park was conducted by the Department of Earth Sciences at Simon Fraser University. This study determined that, by 2005, glacier coverage in the park had decreased to 49% of what it was in the early 18th century. The study attributed this decrease to the trend of global temperature change in the 20th century.[15]

A similar study in 2013 by the same authors reinforced that the park's glaciers, along with others in western Canada, are at the smallest they have been in several thousand years.[16]

Ecology

Flora

Garibaldi's vegetation is altitudinally zoned. The lower slopes of the park, between 1,000 and 1,700 metres (3,300 and 5,600 ft) above sea level, are dominated by dense forests of douglas-fir, western red cedar and western-hemlock. Forests of mountain hemlock, yellow cedar, alpine fir, and white bark pine are present in the higher elevations, and these eventually give way to parkland featuring the characteristically stunted trees of subalpine climates.[9][17]

Much of the park resides in the alpine and subalpine zones, and the park's alpine meadows are carpeted by many species of alpine plants, including heather, western anemone, lupine, arnica, Indian paintbrush, and avalanche lily. The park's flowers are typically most prominent in August.[18]

Fauna

Wildlife thrives in Garibaldi Park, including mammals such as grizzly and black bears, mountain goat, deer, marmot, and pika. A number of birds are present in the park, including golden eagle, bald eagle, blue jay, whiskey jack, and ptarmigan.[17]

As part of the park's 1990 management plan, an assessment was done on the park's mountain goat population in the Spearhead area,[19] which at the time numbered from 50 to 70 individuals.[20] The goal, supported by the provincial conservation framework of BC, was to maintain healthy, viable populations of the animal, thus preventing it from entering "at risk" status. Monitoring flights in March 2012 and March 2013 determined this population was "relatively stable and healthy",[20] but as this was limited to the Spearhead area, no determination of the status of mountain goats throughout the park was made.

Recreational use

Garibaldi Provincial Park is an outdoor recreation destination, featuring many kilometres of hiking trails, campgrounds, and winter camping facilities. In 2016, the park was receiving enough traffic to prompt the province to require advance online bookings for all overnight stays. Prior to this change, campers wishing to stay overnight could register on the day of their arrival in the park. This made Garibaldi Park the third BC provincial park to implement this requirement (the others being Bowron Lake Provincial Park and Berg Lake in Mount Robson Provincial Park).[21]

While the most popular activities in the park are hiking and backcountry camping, other activities include fishing, swimming, canoeing/kayaking, rock climbing, mountaineering, mountain biking, and backcountry skiing.[6] All of the access points, and most of the man-made facilities, are located on the west side of the park, while the eastern wilderness of the park is more remote and less frequented by humans.[22]

Access points

The park has five main access points, all accessed from the Sea to Sky Highway. Each connects to a specific region of the park, though it is possible to access multiple regions from some access points by following the park's interconnected trails.[23]

- Diamond Head is the southernmost entrance. It provides hiking and skiing access to the area south of Mount Garibaldi, including Mamquam Lake, Red Heather Meadows, and Elfin Lakes.

- The Black Tusk/Garibaldi Lake entrance is located roughly half way between Squamish and Whistler, and can be used to reach Garibaldi Lake via a steep trail with many switchbacks. The Garibaldi Lake and Taylor Meadows campgrounds can be reached using this trail. This entrance also provides access to The Black Tusk and Panorama Ridge, and connects to Cheakamus Lake through a trail to the north.

- Cheakamus Lake is an entrance located just south of Whistler, providing access to Cheakamus Lake, and connecting to other trails further south in the park.

- Singing Pass is accessed from the community of Whistler. This entrance follows Fitzsimmons Creek, between the Whistler and Blackcomb mountains, to the Singing Pass area. An alpine route also connects to Singing Pass from the top of whistler.

- Wedgemount Lake is the northernmost entrance to the park. It is reached via a deactivated forest service road, providing access to Wedgemount Lake.

Camping

Garibaldi Park has both walk-in and wilderness camping, as well as some shelters. All walk-in campgrounds must be reserved before use, while wilderness camping (i.e. camping in areas other than designated tent pads) is only allowed in the Garibaldi Wilderness Camping Area,[24] which is away from the more trafficked areas of the park and carries some wilderness-specific rules and guidelines.[25] A total of 11 walk-in campgrounds exist in the park, albeit one campground, Red Heather Meadows, is only open during the winter season.[6] The walk-in campgrounds have anywhere from 6 sites at the Singing Creek campground, to 50 sites at the Garibaldi Lake Campground.

There are four overnight-use shelters in the park:

- Elfin Lakes Shelter is located at Elfin Lakes and is reservable year round. This shelter can house 33 people and contains propane burners, which are supplied with propane by BC Parks.

- Russet Lake Hut was originally built in 1968, and is also known as the Himmelsbach Hut.[26] This small cabin at Russet Lake is used as a cooking shelter and bear cache, and sleeps 6. Plans are in place to replace the Russel Lake Hut as part of the Spearhead Huts project.[27]

- Wedgemount Lake Hut was built at Wedgemount Lake in 1970,[28] and is a basic hut mostly intended to be used as an emergency shelter.

- Burton Hut, also known as the Sphinx Hut, is located across from the Garibaldi Lake campground at the base of Sphinx Glacier and can house 10–15 people. It was built by the University of British Columbia's Varsity Outdoors Club in 1969.[29]

Hiking

The park features over 90 kilometres (56 mi) of park-maintained trails,[6] accessible year-round, although winter hiking requires use of snowshoes or skis. Some of the common routes include:

- Garibaldi Lake Trail, which takes hikers to Garibaldi Lake and the corresponding campground.

- Panorama Ridge Trail, which ends at a spectacular viewpoint overlooking Garibaldi Lake.

- The Black Tusk Trail, with trailheads at Garibaldi and Cheakamus Lake. This trail reaches the base of The Black Tusk, with an optional perilous scramble leading to the top of the peak.

- Elfin Lakes Trail, which leads to the lakes and is most commonly visited in the summer. This trail also provides access to the Opal Cone and Mamquam Lake.

- Wedgemount Lake Trail, a steep hike leading to Wedgemount Lake.

Other activities

- Winter sports are a common use of the park during the snowy months. Most of the park can be accessed in the winter by ski touring, and the Diamond Head area is particularly popular in the winter months.

- Fishing is allowed with a permit at Garibaldi, Cheakamus, and Mamquam lakes.

- Canoeing and kayaking is allowed at Cheakamus Lake only.

- Swimming is permitted at Elfin Lakes (in designated areas), Garibaldi, Cheakamus, Russet, and Wedgemount lakes, although there are no lifeguards on duty. Being glacier fed, the lakes are very cold year-round.

- Rock climbing is possible at various granite walls around the park, and can be found using local climbing guidebooks. Climbing the Black Tusk is generally not recommended due to loose, unstable rock.

- Cycling, although prohibited in most of the park, is allowed on parts of the Elfin Lakes trail and Cheakamus Lake trail.

- Mountaineering is one of the oldest outdoor sports practised at the park, ever since the first summit of Mount Garibaldi. Many of the park's peaks have been summitted and provide ample opportunity for mountaineering and alpinism.

References

- "Protected Planet | Garibaldi Park". Protected Planet. Retrieved 2020-10-16.

- "BC Parks 2017/18 Statistics Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-07-16. Retrieved 2020-07-16.

- "BC Geographical Names". apps.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-05-30. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- Reimer/Yumks, Rudy. "Squamish Nation Cognitive Landscapes" (PDF). McMaster University: 5, 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-03-16. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- "BC Geographical Names". apps.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- Environment, Ministry of. "Garibaldi Provincial Park - BC Parks". www.env.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- "BCMC - Club History". bcmc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-06-05. Retrieved 2019-06-05.

- "Golden Ears Park". BC Geographical Names.

- Osborn, Gerald D.; Clague, John J.; Menounos, Brian; Koch, Johannes (2004-09-01). "Environmental Change in Garibaldi Provincial Park, Southern Coast Mountains, British Columbia". Geoscience Canada. 31 (3). ISSN 1911-4850. Archived from the original on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- "Garibaldi Provincial Park - Canadian Glacier Inventory Project". web.archive.org. 2018-06-04. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- "Wedge Mountain". bivouac.com. 2019-05-30. Archived from the original on 2019-05-30. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

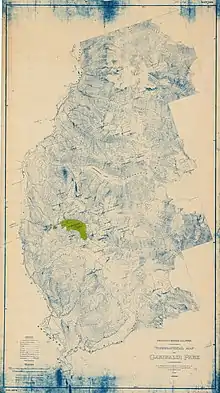

- "Topographical map of Garibaldi Park". City of Vancouver Archives. 1928. Archived from the original on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- Moore, D. P.; Mathews, W. H. (July 1978). "The Rubble Creek landslide, southwestern British Columbia". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 15 (7): 1039–1052. doi:10.1139/e78-112. ISSN 0008-4077.

- Environment, Ministry of. "Ministry of Environment - Garibaldi". www.env.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-05-12. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Koch, Johannes; Menounos, Brian; Clague, John J. (3 December 2008). "Glacier change in Garibaldi Provincial Park, southern Coast Mountains, British Columbia, since the Little Ice Age". Global and Planetary Change. 66 (3–4): 161–178. doi:10.1016/j.gloplacha.2008.11.006. Archived from the original on 2019-05-31.

- Koch, Johannes; Clague, John J; Osborn, Gerald (2014-07-11). "Alpine glaciers and permanent ice and snow patches in western Canada approach their smallest sizes since the mid-Holocene, consistent with global trends". The Holocene. 24 (12): 1639–1648. doi:10.1177/0959683614551214.

- "Garibaldi Provincial Park". www.spacesfornature.org. Archived from the original on 2019-05-03. Retrieved 2019-05-30.

- "PARKS.GaribaldiPDF" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. 2019-05-30. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-30.

- "Garibaldi Provincial Park Master Plan" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. September 1990. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- "Garibaldi Park - Management Plan Amendment for the Spearhead Area" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. February 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-03-03. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- "Garibaldi Provincial Park reservations now required for backcountry campers". CBC News. 2016-06-22. Archived from the original on 2019-01-17. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- "Garibaldi_Provincial_Park_2008" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. 2019-05-31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "Park Map" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. June 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-06-03. Retrieved 2019-06-03.

- "map-wilderness-camping-garibaldi" (PDF). eng.gov.bc.ca. 2019-05-31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-05-31.

- Environment, Ministry of. "Visiting Parks - BC Parks - Province of British Columbia". www.env.gov.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 2019-05-18. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "Russet Lake Hut". Bivouac. 2019-05-31. Archived from the original on 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "FAQ's – Spearhead Huts Project". Archived from the original on 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- "The Wedge Hut at Wedgemount Lake". whistlerhiatus.com. Archived from the original on 2019-05-31. Retrieved 2019-05-31.

- Burton, Roland (1969). "Sphinx hut" (PDF). VOCJ. 12: 47–51.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Garibaldi Provincial Park. |

- BCParks - Garibaldi page

- - UN database entry

- - History of Park and Area - Virtual Museum of Canada

- - Garibaldi Park 2020 - History of Park and Mapping

.jpg.webp)