Garre

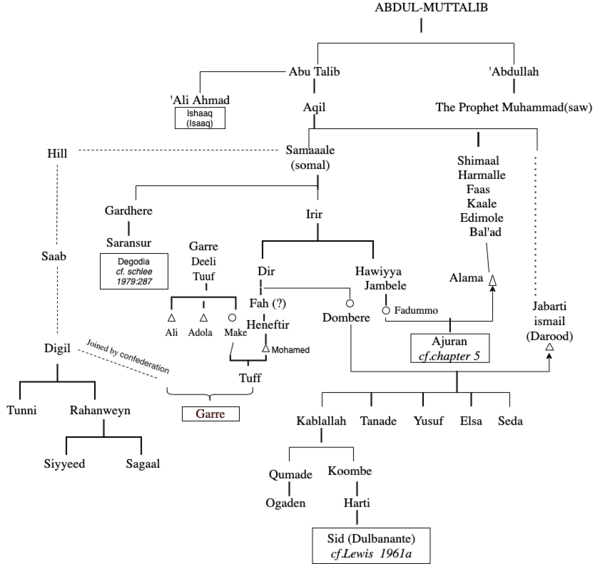

The Garre (Somali : Garre, Arabic: غرِّي ) are a Somali pastoralist clan whose origins are all traced back to Patriarch Samaale who traces the lineage from the Arabian Peninsula through Aqiil Abu Talib.[1][2] The Garre clan are considered to belong to the Digil clan family hence sub-clan of Digil-Rahaweyn clan of Rahaweyn Somali clan but genealogically descend from Garedheere Samaale.[1]

Somali | |

|---|---|

| |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

| Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

History

General introduction

The Garre are of Samaale[2][3] origin being descendants of Samaale[1][2] with one evidence tracing their lineage to Mayle ibn Samale,[4] and the other to Garedheere ibn iSamaale,[1] both sons of Samaale.[5] Garre is divided into two major clans, Garre Tuuf which is associated with 'Pre-Hawiye' group (Gardere - Yakabur - Mayle)[4] while the Quranyow Mohamed have traditional links to the Dir sub-clans of Mohamed Xinfitire. The Garre joined Rahaweyn constituent sub-clans of Digil, forming a part of the Rahaweyn confederation of clans.,[2][6] this was due to the fruit of nomadic life, the necessity of defense, the movement of new territory necessitated by a constant search for pasture and water have resulted over formation of new alliances and later, new clan identities. This show's indeed the Somali saying "tol waa tolane'' ( clan is something joined together) and the structure is not based on blood relationship, that is why you you'll find Garre is closely affiliated with Tunni and Jiido of the Lower Jubba Valley.

The Garre, a section of the Pre-Hawiye Somali or proto-Garre Somali gained control of the area between the Juba and the Tana rivers before the Galla arrived in this area,[7][1] and that in the process the Garre were responsible for pushing Bantu-speaking peoples back to the river Tana. The Garre, Pre-Hawiye group have been the first group to occupy the land between the Jubba and Tana Rivers prior to Oroma. The Arabs, who inhabited the Kismayu coast and islands parrallel to the coast about 1660, and to whom local tombs and ruins are attributed, exterted considerable influence on the formation of the present-day characteristics of the Bajuni were also routed by the Somali Garre whom the Bajuni claims as ancestors- perhaps they were at one time Gerra clients.[8]

Support for such a thesis was mainly based on the fact that the Garre group is the most widely dispersed among the Somali clans.[1]

The Garre are a tribe of Somali origin who entering the country of the East, extended up the right bank of the Dawa as far as Guba Gallgalo. This place is looked on as a tribal headquarter and is the burying place of the chiefs. The Garre adopted the Galla language when they became subject to the Boran Kingdom which at the Zenith of its power extended along the Dawa to within 30 miles of its mouth, and as far south of El Wak. The Garre have recovered their independence but even know some of the wells at the El Wak belong to Boran families living in the highlands.[9]

The scattering of Garre is also supported by the small remnants they supposedly left along the routes they took in their migration. This is soo-called Boon Garre at the Afmadu, other boon Garre at Gelib near the mouth of the River Jubba and still others on the RIver Tana who spoke not the dialect of their Darood dialect neighbours rather the southern Somali dialect[1][10] of the Rahaweyn speech variety because they had lived in Rahaweyn speaking area between the Jubba and Shebelle rivers, and yet other who lived around Baardhere and kept their own original somali like language (Garreh Kofar). As all these re-migrant of different linguistic affiliation now share the same pastures again, a remarkable degree of multilingualism has developed, many individuals herdmen speak all three of these languages (Borana, Garreh Kofar, Rahaweyn)[11] and , in addition often some Standard Somali or Swahili.

The Pre-Hawiye

The Pre-Hawiye, a much-reduced tribal-family, trace descent from an ancestor collateral to Irrir, and are accordingly genealogically anterior to the Hawiya. Their traditions show them to have preceded the Hawiya in the general expansions of the northern Somali towards the south. For these reasons Colluci has coined the term 'Pre-Hawiya' to distinguish them from the Hawiya to whom they are closely related.[1][12]

The family comprises the Gilale, Ormale, Hon, Daule, Hober, Hawadle, and Gerra (or Garre).[13]

The Gilale survive in small groups in the Doi and Afgoi-Geledi valley. The Ormale have traditions of movement from the region of the Badi-Addo. Some are found along the Juba among the WaGosha, but most are Helai clients, The Hon have representatives among the Harien. The Daule occur in small groups in the hill-country between the Shebelle and Juba Rivers. Their traditions, which are typical of the pre-Hawiya, record conquest by the Digil.[13][5] The Hober formerly occupied the present territory of the Hadama near Hodur, whence they were dispersed by the Digil invaders after a series of wars with Rahanwein Sagal, Hadama, Luwai, Gelidle and Jelible. They were finally by the magical powers of the Sheik District as cultivators associated with Shan Dafet tribal clusters.[13][5]

The Hawadle are an important tribe of nomadic pastoralists, living north of the Abgal and along the Shebelle , where the fertile riverine lands are cultivated by their freedmen.[14][5]

The Garre are the most important tribe of the pre-Hawiya family.[14] They occur in four large autonomous groups: on the lower reaches of the Shebelle in Audegle District around Dolo on the upper jubba, between the Webi Gestro and the Webi Mana in contact and to some extent intermixed with the Arussi Galla, and to the south-west between the Ajuran and Degodia Somali and the Boran Galla of the Northern Frontier Province of Kenya.[5][14] The northernmost group adjacent to the Galla Arrusi have acquired some features of Galla culture; Galla and Somali are both spoken. Galla Arussi villages are intermixed with those of the Garre (Gurra) but are kept separate from those of the Somali.[5][14] The Garre of this region have traditions simillar to those of the other groups and consider themselves Somali rather than Galla.[5][14] Garre traditions generally recount movement southwards from the North-west corner of British Somaliland. Many small groups occur as clients among the Galjaal and Rahaweyn. As a whole, the Garre are nomadic pastoralists with large numbers of camels, sheep, goats and where the habitat is suitable, cattle

Rahanweyn

Rahanweyn tribes are aggregates of many diverse clan attached to a small original nucleus of Rahanwein,[15] who form the dominant eponymous clan and provide the skeletal framework in each tribe. In many cases, however, this type of organization, dependent for its structure on a dominant clan, is superseded by a system of territorial groups whose political relations are not expressed genealogically.[15] In the Rahawein family itself there are only three orders of segmentations between the group-name and ancestor Rahawein, and the individual tribes which constitute the family. The Rahaweyn consists no so much of groups that derive from preceding groups in an extensive hierarchy of segmentation, as simply of large collateral coalitions. The name "Rahaweyn" ( "large crowds") is itself suggestive of federation.[15] The Sab, who number about a quarter millions are found in Somalia south of the Hawiya, mainly along the Juba river. They are segmented into three families: The Digil, Rahaweyn and Tunni of which the last two are numerically the most important. The Rahaweyn and Tunni derive from the Digil who although have been superseded in strength still survive as a small independent confederacy.[16] The Garre joined Rahaweyn constituent sub-clans of Digil, forming a part of the Rahaweyn confederation of clans.[2][6]

Dir - Quranyow ("Gorajno")

The Dir family are the oldest Somali stock, have been greatly dispersed and so reduced that only three main tribes survived. These are the Essa, Gadabursi and Bimal. The Esa and Gadabursi are found to the north-west of British Somaliland, with some Esa in the French Somaliland and some Gadabursi in the Abyssinian territory which is the traditional Dir country. In the present day knowledge, it is not possible to say with certainty that the Gadabursi are Dir, but they seem to be, and are always classified as such by the Italian authorities.[19][18]

The most southernly representatives of the Dir family are the Bimal of Somalia who are found in the two regions-one of the Shebelle centred round merca and the other the Juba River and the Tunni of Brava. At Merca, where the administration has encouraged cultivation by constructing irrigation canals, maize, durra, beans, sesame, tobacco and watermelon are grown.[18][20] The Bimal reached their present territory towards the close of the 18th century in thee course of the general movement of the Somali from North to South. Groups which did not succeeded in maintaining their tribal autonomy so successfully as the Bimal in their dispersal from the North, are the Dabrui living among the Bimal of Merca, the Bajumal among the shebelle Negroids, the Gorajno ( Quranyow) with the Garre, the Madaweni among the WaGosha and in the Abyssinia a dn the Madeluk found among the Ogaden, Helai, Shebelle, in Jubaland and at Serenlei and Margherita[18][20]

Demography and Social Organisation

Most Garre are nomadic herdsmen, seasonally migrating with their camels, sheep, and goats. They live in portable huts made of bent saplings covered with animal skins or woven mats. Their collapsible tents can easily be loaded on pack animals and moved with the herds. The wealth of most Garre is in their herds. Although the husband remains the legal owner of the herd, his wife controls part of it.

Garre villages consist of several related families. Their huts are arranged in a circle or semi-circle surrounding the cattle pens. Villages are enclosed by thorn-shrub hedges to provide protection from intruders or wild animals. The men's responsibilities include caring for the herds, making decisions dealing with migration, and trading. The women are in charge of domestic duties, such as preparing the meals, milking the animals, caring for the children, and actually building the home. Like other nomads, the Garre scorn those who work with their hands, considering craftsmen a part of the lower class.

The moving patterns of Garre nomads are dependent upon climate and the availability of grazing land. If water or grazing land becomes scarce, the families pack up their portable huts and move across the desert as a single, extended family unit. The Garre are quite loyal to one another, spreading evenly across the land to make sure that everyone has enough water and pasture for his herds.

Distribution

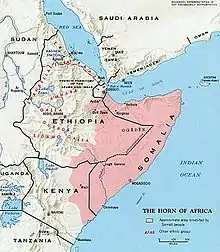

Garre are said mostly to be found In Southern Somalia, on the Lower reaches of the Shabelle River; Afgooye, around Dolo around the upper Jubba; between Webi Gesho and Webi Maana River, Qoroyoley, Merca, and Awdhagle Districts, and Kaxda District & Kofur in Mogadishu, El Wak District in Gedo Jubaland. and in the upper reaches of Dawa River on the borders of Ethiopia and Kenya.[1] This, in turn, is based on the Garre oral traditions( collected at the beginning of the century) that they migrated from the upper reaches of the Jubba River along the west side of the River Afmadu. In Ethiopia, they live in Moyale, Hudet, Mubarak, Qadaduma, Suruba, Raaro, Lehey and Woreda of Dawa zone. In Kenya, the Garre tribe inhabit Mandera County-(The largest population and composition of Garre live in Mandera County, making them the single largest clan in Mandera County),[21] Wajir, North Moyale, as well as part of Isiolo County.

Both the Garre and Ajuran claim to have lived in their present location in Mandera District (formerly Garreh District) and the Northern part of Wajir District before the sixteenth-century expansion of the Oromo, According to tradition Gurreh District was originally inhabited by a Semitic tribe ben-Izraeli before inhabited by Garre tribe.[22] before setting out to prospect for a new country. They travelled down the Juba through Rahaweyn to Kofar (confor) and decided it was a good country.[23]

The Confer (Kofar) country lies beyond Rahanweyn in the coastal area, the principal Gurreh towns or villages being Shan and Musser on the Owdegli i.e. the lower reaches of the Shebelle River where it runs parallel with and close to the sea coast between Mogadishu and Merca. Then when well established and prosperous the Garre penetrated into Rahanweyn and sent trading safaris and settlers further in-land until they reached Lugh and Dolo and re-entered the Gurreh district (today Mandera District] and worked up the Daua district (sic: actually 'river'] again, trading mostly but also making settlements and farms. [22][23]

Garre is divided into four linguistic clusters, which cross-cut other criteria of differentiation like clanship. Some of them speak an Oromo dialect close to the one of the Boran, while some speak Af Rahanweyn and yet others Af Garreh Kofar. The latter two are closely related Somali-like languages but are kept clearly apart by their speakers. There are also Garre who speak Somali proper. Oromo is a different language well beyond the comprehension of speakers of any of these Somali dialects. It belongs to the same lowland branch of the East Cushitic languages as the Somali-type languages, but internal differentiation within this branch is high. The fact that the Garre are also divided between three nation-states (Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia) has nothing to do with this linguistic differentiation since speakers of all four languages are found among the Garre of all three states. The only language which is spoken exclusively by Garre appears to be Af Garreh Kofar, but to the outside observer, it is difficult to distinguish that language from Af Rahanweyn (also called Maymay), which is spoken by hundreds of thousands of non-Garre, namely Somali of the Rahanweyn clan cluster. It does happen that Garre who do not share one of these Cushitic languages are obliged to converse with each other in languages from totally different language families, like Swahili or English which they have acquired at school, an institution frequented by only a minority of them, mostly for short periods.[24] Arabic is also spoken as a secondary or trade language. Like other Somali, the Garre are typically tall and slender with long, oval faces and straight noses. Their skin colour varies from jet black to light brown.

Af-Garre (Garreh Kofar) is spoken in the districts of Baydhaba, Dhiinsor, Buurhakaba and Qoryooley is one of the heterogeneous dialect of Somalia; in fact, some Garreh Kofar dialects ( those in Buurhakaba and Qoryooley) have, for instance, preserved the conjugations with prefixes to date, while others (those of Baydhaba) have already given it up. Also, the typical Digil plural morpheme—to has been replaced in some Gr. dialects (especially in those around Baydhaba) by the common southern Somali morpheme—yaal. Although Reer Amiir are not Garre at all, their idioms belong to this dialectal group.[25]

Garre genealogy and clan structure

The following genealogy has been derived from the work of Professor L.M.Lewis, also taken also from the World Bank's Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics[26] from 2005 and the United Kingdom's Home Office publication, Somalia Assessment 2001,[27] and The Total Somali Clan Genealogy (second edition), African Studies Centre Leiden, Netherlands [28] The tribes of Garre have a well-defined patrilineal genealogical structure,

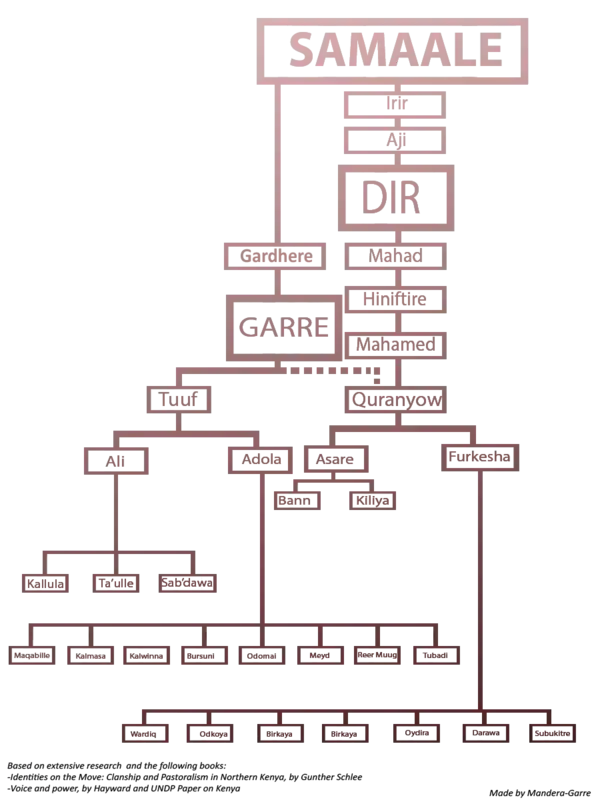

The Garre are divided into the Tuff and Quranyow sub-clans. While the Tuffs are further divided into the Ali and Adola groups, the Quranyow are divided into the Asare and Furkesha.[29][30]

In history, Identities on the Move: Clanship and Pastoralism in Northern Kenya, by Gunther Schlee, Voice and Power, by Hayward and UNDP Paper on Kenya, the Garre are divided into the following clans.[22][29][30] The Garre split in 2 great sub-clans, Tuf and Kuranyo. The Kuranyo are Garre by marriage. Kuranyow who married Tuf's daughter Make, became part of the Garre confederation. The Garre are all associated with the four Dir ancestral progenitors but allied themselves to the Digil Rahanweyn confederacy

The eponymous ancestor of Garre clan:

- 'Abd al Muttalib

- Abu Talib

- Aqil

- Hiil

- Samaale

- Gardhere

- Garre :

- Tuuf

- Ali

- Kalulla

- Ta'ule

- Sabdawa

- Adola

- Maqabille

- Kalmasa

- Kalwina

- Burusuni

- Oldomai

- Meyd

- Reeg Muug

- Tubaadi

- Ali

- Quranyow

- Asare

- Baan

- Kiliya

- Furukesha

- Wardiq

- Odkoya

- Birkaya

- Oydira

- Darawa

- Subukitre

- Asare

- Tuuf

- Garre :

- Gardhere

- Samaale

- Hiil

- Aqil

- Abu Talib

References

- The invention of Somalia. Ahmed, Ali Jimale. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press. 1995. pp. 88–89. ISBN 0-932415-98-9. OCLC 31376757.CS1 maint: others (link)

- The invention of Somalia. Ahmed, Ali Jimale. Lawrenceville, NJ: Red Sea Press. 1995. p. 122. ISBN 0-932415-98-9. OCLC 31376757.CS1 maint: others (link)

- Ahmed, Ali Jimale (1995-01-01). The Invention of Somalia. The Red Sea Press. p. 131. ISBN 9780932415998.

- "The Total Somali Clan Genealogy (second edition)".

- Lewis, I. M. (2017-02-03). Peoples of the Horn of Africa (Somali, Afar and Saho). doi:10.4324/9781315308197. ISBN 9781315308197.

- Worldbank, Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics, January 2005, Appendix 2, Lineage Charts, p.55 Figure A-1

- Turton, E. R. (1975). "Bantu, Galla and Somali Migrations in the Horn of Africa: A Reassessment of the Juba/Tana Area". The Journal of African History. 16 (4): 519–537. doi:10.1017/S0021853700014535. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 180495.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 42–43. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- Ian, Brownie (1979). "African Boundaries". A Legal and Diplomatic Encyclopedia: 783–788. ISBN 9780903983877.

- Mauro Tosco. 2012. The Unity and Diversity of Somali Dialectal Variants. In Nathan Oyori Ogechi and Jane A. Ngala Oduor and Peter Iribemwangi (eds.), The Harmonization and Standardization of Kenyan Languages. Orthography and other aspects, 263-280. Cape Town: The Centre for Advanced Studies of African Society (CASAS).

- "Dynamics and Trends of Conflict in Greater Mandera" (PDF).

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 25–26. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 25–27. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. p. 27. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 34–40. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994) (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 15–18. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 25–27. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- Lewis, I. M. (2017-02-03). Peoples of the Horn of Africa (Somali, Afar and Saho). doi:10.4324/9781315308197. ISBN 9781315308197.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. p. 25. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- I. M., Lewis (1994). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho (Ethnographic Survey of Africa; North Eastern Africa, Part I). Haan Associates; New Edition. pp. 25–26. ISBN 1874209-56-1.

- UNDP paper

- Schlee, Günther (1989-01-01). Identities on the Move: Clanship and Pastoralism in Northern Kenya. Manchester University Press. p. 5. ISBN 9780719030109.

- J.W.K, Pease (1928). An Ethnological Treatise Of The Gurreh Tribe. KNA.

- Schlee, Günther (2010). How Enemies are Made: Towards a Theory of Ethnic and Religious Conflict (NED - New edition, 1 ed.). Berghahn Books. pp. 160–161. ISBN 978-1-84545-779-2. JSTOR j.ctt9qd3d3.

- Andrzej, Zaborski (1986). Map of Somali Dialects In The Somali Democratic Republic. Gemsamtherstellung: HELMUT BUSKE VERLAG HAMBURG. pp. 24–25. ISBN 3871186902.

- Marchal, Roland (2019-03-01), "Motivations and Drivers of Al-Shabaab", War and Peace in Somalia, Oxford University Press, pp. 309–317, doi:10.1093/oso/9780190947910.003.0027, ISBN 978-0-19-094791-0, retrieved 2020-12-29

- "Somalia Assessment" (PDF). Somalia Assessement 2001. 2001.

- Abbink, G.J. (2009). "The Total Somali Clan Genealogy (second edition)".

- Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (2005-08-17). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 9781135751753.

- UNDP paper (Kenya)