Habr Awal

The Habr Awal (Somali: Habar Awal, Arabic: هبر أول, Full Name: Abdirahman Sheikh Ishaaq ibn Ahmad; also known as Zubeyr Awal, or Subeer Awal)[1] is a major Somali sub-clan of the wider Isaaq clan family, and is further divided into several sub-clans of whom the two largest and most prominent are the Sa'ad Musa and Issa Musa sub-clans. Its members form a part of the Habr Magaadle confederation. The Habr Awal traditionally consists of nomadic pastoralists, coastal people, merchants and farmers. They are historically viewed as an affluent clan relative to other Somali clans.[2] The Habr Awal are politically and economically influential in present-day Somaliland, and reside in strategic coastal and fertile lands.[3][4]

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Languages | |

| Somali, Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Sunni) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ayub, Arap, Garhajis, Habr Je'lo and other Isaaq groups |

Distribution

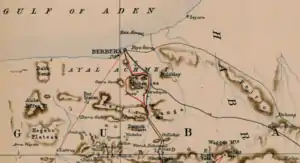

The Habr Awal clan make up the majority in Maroodi Jeex region which is considered the most populous region in Somaliland, forming a majority in the national capital Hargeisa as well as exclusively dominating in the agricultural towns and settlements of Gabiley, Wajaale, Arabsiyo, and Kalabaydh. The Habr Awal are also prevalent in Sahil region, principally in the regional capital and port city of Berbera, and the historic town of Sheikh as well as Daarbuduq. The clan also partially inhabits the northern portion of the capital city of Burao in Togdheer region as well. The Habr Awal also partially inhabit the neighbouring region of Awdal, namely in eastern Lughaya. Outside of Somaliland, the Habr Awal also have large settlements in the Somali region of Ethiopia, specifically in Fafan Zone where they respectively make up the majority in Harshin, Hart Sheik, and Wajaale (Ethiopian Side) towns. They also settle and border Kebri Beyah and Jigjiga in the Fafan Zone. They also have a large settlement in Kenya where they are known as a constituent segment of the Isahakia community.[5] Finally they have a large presence in Djibouti as well, forming a large percentage of the Somali population in Djibouti and within Djibouti they have historically settled in Quartier 3, which is one of the 7 major districts in Djibouti.[6][7][8]

History

Lineage

Sheikh Ishaaq Bin Ahmed was one of the Arabian scholars that crossed the sea from Arabia to the Horn of Africa to spread Islam around 12th to 13th century. He is said to have been descended from Prophet Mohammed's daughter Fatimah. Hence the Sheikh belonged to the Ashraf or Sada, titles given to the descendants of the prophet. He married two local women in Somalia that left him eight sons, one of them being Abdirahman (Awal). The descendants of those eight sons are the what is known as Isaaq clan today.

The grave of Zubeyr Awal, the eponymous ancestor of the Habr Awal subclan of the Isaaq, is located in Jidali in Sanaag which is about 100 km east of the tomb of his grandfather Sheikh Ishaaq Bin Ahmed, the founding father of the Isaaq clan, whose tomb is located in the coastal town of Maydh.

Medieval Period (Conquest of Abbysinia)

Historically the Habr Awal were part of the Adal Sultanate and are mentioned in the renowned "Futuh Al-Habash" for their major contributions in the Abyssinian-Adal war as the Habr Magaadle along with the Garhajis, Arap and Ayub clans against the Abyssinian empire, and also for producing a historical figure known as Ahmad Girri bin Husain who was the righthand partner of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi and a chieftain for the Habr Magaadle forces during the Abyssinian–Adal war.[9]

Pre-colonial era

_(14586268478).jpg.webp)

The Habr Awal have a rich mercantile history largely due to their possession of the major Somali port of Berbera, which was the chief port and settlement of Habr Awal clan during the early modern period.[10] The clan had strong ties to the Emirate of Harar and Emirs would hold Habr Awal merchants in their court with high esteem with Richard Burton noting their influence in Emir Ahmad III ibn Abu Bakr's court and discussions with the Vizier Mohammed.[11]

The Habr Awal as a whole are a rich people, mainly thanks to the trade passing through the port of Berbera which lies in the territory of the Sa’ad Musa.[12]

In this way the tribes occupying the tract of country through which the main caravan or trade routes passed accumulated a good deal of wealth, while those like the Ayal Ahmed, fortunate enough to possess a port so favored by Nature as Berbera, naturally soon became rich.[13]

The Habr Awal merchants had extensive trade relations with Arab and Indian merchants from Arabia and the Indian subcontinent respectively. When these foreign traders arrived in Berbera and Bulhar to conduct trade, there was a mutually beneficial arrangement based on the abban (protection) system between them and the local Reer Yunis Nuh (Ayyal Yunis) and Ahmed Nuh (Ayyal Ahmed) lineages of Sa’ad Musa, Habr Awal:

Before this, and prior to the British settlement at Aden in 1839, the Ayyal Yunis and Ayyal Ahmed lineages of the Habr Awal clan had held Berbera and jointly managed its trade, sharing in the profits on all commercial transactions as ‘protectors’ (abans) of foreign merchants from Arabia and India. When under the stimulus of developments at Aden the port's prosperity markedly increased, the numerically dominant Ayyal Yunis drove out their rival kinsmen and declared themselves commercial masters of Berbera. This led to a feud in which each side sought outside help; the defeated Ayyal Ahmed turned to Haji Shirmarke ‘Ali and his Habr Yunis clansmen for support. With this backing, they were then able to re-establish themselves and to expel the Ayyal Yunis who moved to the small roadstead of Bulhar, some miles to the west of Berbera.[14]

Not only did the Habr Awal host foreign merchants at their ports, they also conducted trade missions on their own vessels to the Arabian ports.[15] The majority of the Somali merchants who frequented Aden and other Southern Arabian ports hailed from the Habr Awal clan. They procured various raw goods from Harar and the interior in exchange for manufactured goods. During their stay, the Habr Awal rented their own houses and hired their own servants, whereas other Somali clans tended to stay with relatives already established across the Gulf.

Merchants. — These are generally members of the Habr Awal tribe. They bring from Harrar and the Galla country, coffee, saffron (bastard), tusks (ivory), and feathers, taking away in return zinc, brass, broad cloth, and piece goods. They remain in Aden for about twenty days at a time during the trading season, which lasts about nine months,' making four trips. During their residence they hire a house, and are accompanied by their own domestics.[16]

In the interior, Habr Awal trade caravans (khafilas) were a frequent sight according to contemporary European accounts of the Somali Peninsula:

On leaving Hargeisa we travelled for many miles through beautiful park-like land, alive with birds and jungle fowl. We met the usual Somali khafilas [trading caravans] of Habr-Awal men, carrying their skins, gums, ghee, and coffee to our port at Bulhar, situated between Berbera and Zeila.[17]

The Somalis from the deep interior, principally those from the Ogaden, also gained most of their resources from the Habr Awal merchants who they called "iidoor", an enviable pejorative meaning merchant or trader, a reference to the mercantile nature of the Habr Awal traders at the time.[18] The coastal Habr Awal (mainly the Reer Ahmed Nuh) regularly acted as brokers/middlemen for the Somali clans of the interior who wished to take their goods to the ports of Berbera and Bulhar:

The custom is for the Ayal Achmet (Berbera tribe) to act as brokers, and too often most of the profits stick to the hands of the middleman. Till lately no Ogadayn ever went to the coast, but entrusted the goods to coast traders.[19]

Berbera Blockade

When a British vessel named the Mary Anne attempted to dock in Berbera's port in 1825 it was attacked and multiple members of the crew were massacred by the Habr Awal. In response the Royal Navy enforced a blockade and some accounts narrate a bombardment of the city.[20] The Qasimi were very active both militarily and economically in the Gulf of Aden and were given to plunder and attack ships as far west as the Mocha on the Red Sea.[21] They had numerous commercial ties with the Somalis, leading vessels from Ras Al Khaimah and the Persian Gulf to regularly attend trade fairs in Berbera and Zeila.[22] Given the reputation of the Qasimis as notorious pirates, the Isaaq Sultan Farah and Haji Ali penned a letter to Sultan bin Saqr Al Qasimi informing him of the situation and requested he join them in their conflict against Britain. However, the Sultan was unable to respond or help relieve the blockade as the Persian Gulf campaign of 1819 had incapacitated his fleet.[23] In 1827 two years later the British extended an offer to relieve the blockade which had halted Berbera's lucrative trade in exchange for a commercial treaty and 15,000 Spanish dollars to be paid by the Habr Awal leaders for the destruction of the ship and loss of life.[24]

British Protectorate Period

The Habr Awal clan came under British Somaliland by signing a protectorate treaty with the British Empire on 14 July 1884. The Habr Awal continued to have a lucrative trading agreement with their foreign contacts, many of whom were also under British rule in their respective nations. The British established the capital of the British Somaliland protectorate at Berbera, but later moved the capital to Hargeisa in 1941.[25]

Garaads and Sultans of the Habr Awal

The Habr Awal have a long tradition of leadership and are led by a Sultan from the Ahmed Abdalla branch - a numerous subclan of Saad Musa that mainly reside in Ethiopia.[26] Historically preferring to use the native term Garaad like the Warsangeli, both clans have since changed the name of the title to Suldaan although the role is identical.[27] Habr Awal Garaads would rally men in times of war and settle large disputes with other clans filling the role as the ultimate peacemaker (nabadoon).[28]The first Garaad Biniin was crowned around a similar time as the first Habr Yunis Sultan Diriiye Ainasha, with both of these large subclans breaking from the tutelage of the Eidagale who are the wider leaders of the Isaaq. Following his death, the Habr Awal did not crown a new Garaad for several years as Biniin's heirs were too young, with Garaad Abdalla being crowned when he came of age. Fighting in the southern limits of Habr Awal territory to protect the clan against its enemies and fighting off raids. In one incident he narrowly avoided a Jidwaaq surprise attack with the Ahmed Abdalla rallying quickly and forcing the raiders to flee.[29]

| Name | Reign

From |

Reign

Till | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Garaad Biniin (first Garaad) | ||

| 2 | Garaad Abdalla Garaad Biniin | ||

| 3 | Garaad Askar Garaad Abdalla | ||

| 4 | Garaad Diriiye Garaad Abdalla | ||

| 5 | Sultan Abdulrahman Garaad Diriiye (adopted Sultan title) | ||

| 6 | Sultan Abdillahi Sultan Abdulrahman | ||

| 7 | Sultan Abdirizaq Sultan Abdillahi | ||

| 8 | Sultan Hassan Sultan Abdillahi |

Garaad Abdalla served for several decades and was received by travelling British officials near the southern limit of the protectorate in 1894 concerning expansion by General Ras Makonen on behalf of Menelik II.[30]Garaad Abdalla alongside many other leaders in British Somaliland such as Sultan Deria Hassan and Sheikh Madar were worried about a devastating raid by the Abyssinian forces aimed at the burgeoning town Hargeisa and its environs. The Garaad was contacted by Makonen just two years later asking him and the Habr Awal to join the Ethiopian Empire but was rebuffed.[31] Garaad Abdalla was approached by the Sultan of Habr Yunis when they had faced a drought, the Habr Yunis requested access to Habr Awal wells to water. Abdalla granted the request but some members of his clan thought he was too generous and helping the Habr Yunis at the expense of the wellbeing of their own stock. Chief amongst these people was his 15 year old Askar. When some of the Habr Yunis party came to water, Askar stepped in between the well and the men barring them access. He was reprimanded for his foolishness and told to step aside and obey his father's wishes. Enraged Askar stabbed the man who reprimanded him and war almost broke out at this action.[32]

A wise Habr Awal bard from Bulhar named Aami stood and recited a gabay[33]

- The words too many have already been spoken about Yunis' foolish words

- But righteous judgement pious to you according to ancient custom, bringing peace and (firmly) like a mountain

- Very close to you lurk people, you enemies, from primeval times their commemorating a feud

- If the time came when you were blinded by the quarrel, you would not respect it

- Without hesitation, they suddenly fell upon you

- All hostile tribes have heard the news of your quarrel

- Like vultures, they all look greedily at your flesh!

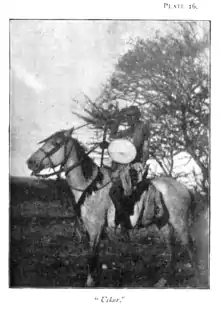

The parties were moved by his words and mediated their dispute. Garaad Abdalla gave the hand of one of his daughters to the poet as a reward for his efforts.[34]Following Abdalla's death, his eldest son Askar succeeded him as Garaad. Askar was a skilled horseman and fought in offensive with the southern sections of the clan against the Dervish who had begun raiding Habr Awal and other clans in the region. Sheikh Madar rallied the northern sections of the Habr Awal who unlike the Ahmed Abdalla and a few others, did reside mainly inside the borders of British Somaliland.[35][36]Following Askaar's death his younger brother Diriiye took the mantle of Garaad and unlike his brother and father was more focused on the concerns of the Habr Awal community as a period of relative peace had set in following the defeat of the Dervishes, decreasing the need for fighting.[37] Diriiye was faced with a parallel challenger to his role as Garaad and the Habr Awal rallied behind him and rebuffed the pretender.[38]

With Diriiye's eventual death, his son Abdulrahman was crowned and the first Habr Awal leader to style himself as 'Sultan' rather than Garaad. Abdulrahman was very much like his father however was much more active in protectorate affairs.[39] When the Eidagale attempted to raid the Issa Musa, a son of the Habr Yunis Sultan joined the raid and when the raiders were pursued he was killed. The Sultan of the Habr Yunis approached Abdulrahman to resolve the dispute and wanted him to compel the Issa Musa to pay mag for the Sultan's son. According to traditional Somali xeer restitution is not paid when one is killed in self defense. So the Issa Musa refused and banged their shields in disproval of Abdulrahman's judgement.[40]

Cismaan Haariyey a poet stood and recited the following geeraar reaffirming his respect but disagreeing with Sultan Abdulrahman. After this the Issa Musa would leave and go on to crown their first Sultan, Sultan Koshin in 1949 marking their independence from their larger Saad Musa brethren.[41]

Ninka Qaaliya joogee |

The man who stands in wealth |

| —Cismaan Haayirey Suldaanow Kuma Caayin[42] |

In the year 1955, Sultan Abdulrahman Deria was a member of a 4 delegation team of politicians and Sultans to London,United Kingdom. Their goal was to petition and pressure the British Government in returning lost treaty territory known as the 'Haud Reserve Area' ceded to Ethiopian Empire during the Anglo Ethiopian treaty of 1954.[43]

In Imperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of Somaliland, 1954-1960, Historian Jama Mohamed writes:

The N.U.F. campaigned for the return of the territories both in Somaliland and abroad. In March 1955, for instance, a delegation consisting of Michael Mariano, Abokor Haji Farah and Abdi Dahir went to Mogadisho to win the support and co-operation of the nationalist groups in Somalia. And in February and May 1955 another delegation consisting of two traditional Sultans (Sultan Abdillahi Sultan Deria, and Sultan Abdulrahman Sultan Deria), and two Western-educated moderate politicians (Michael Mariano, Abdirahman Ali Mohamed Dubeh) visited London and New York. During their tour of London, they formally met and discussed the issue with the Secretary of State for the Colonies, Alan Lennox-Boyd. They told Lennox-Boyd about the 1885 Anglo-Somali treaties. Under the agreements, Michael Mariano stated, the British Government 'undertook never to cede, sell, mortgage or otherwise give for occupation, save to the British Government, any portion of the territory inhabited by them or being under their control'. But now the Somali people 'have heard that their land was being given to Ethiopia under an Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty of 1897'. That treaty, however, was 'in conflict' with the Anglo-Somali treaties 'which took precedence in time' over the 1897 Anglo-Ethiopian Treaty[.] The British Government had 'exceeded its powers when it concluded the 1897 Treaty and ... the 1897 Treaty was not binding on the tribes.' Sultan Abdillahi also added that the 1954 agreement was a 'great shock to the Somali people' since they had not been told about the negotiations, and since the British Government had been administering the area since 1941. The delegates requested, as Sultan Abdulrahman put it, the postponement of the implementation of the agreement to 'grant the delegation time to put up their case' in Parliament and in international organizations.[44]

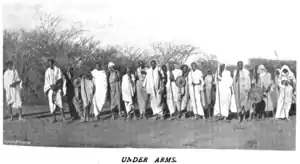

Somali Civil War and the Somali National Movement

The Somali National Movement (SNM) was a 1980s–1990s rebel group. The SNM at 1981 founding in London it elected Ahmed Mohamed Gulaid from the Habr Awal clan as its first chairman, who stated that the group's explicit purpose was to overthrow the Siad Barre military regime.[45] The SNM gathered its main base of support from members of the Isaaq clan, who formed and supported the movement in response to years of systematic discrimination by the Siad Barre government.

Members of the Habr Awal clan made up a significant portion of leaders and soldiers of the SNM. Habr Awal Commanders carried out many successful operations that led to the decisive victory of the group and to the downfall of the Siad Barre regime.

In western Somaliland, this group was prominently represented in the 99 division of the Somali National Movement which was founded in Gabiley with the majority of the divisions troops consisting of militia fighters hailing from the Jibril Abokor section of the Sa'ad Muuse sub-clan of the Habr Awal that dominates the Gabiley region. The 99 division was Commanded by General Mohamed Hasan Abdullahi (Jidhif) of the Jibril Abokor who successfully conquered Awdal region and completely erased the presence of Somali National Army forces within Gabiley and Awdal and forced the local Gadabursi inhabitants of Awdal to pledge loyalty to Somaliland. As commander of the 99 division, General Mohamed Hasan Abdullahi (Jidhif) also established a Somali National Movement military base in Zeila where the SNM occupied the Awdal region for 4 years and successfully defeated attempts by USF militia forces loyal to Djibouti who tried to take advantage of the fall of Siad Barre's Military Junta in 1991 and annex the city of Zeila.[46]

In central Somaliland, Muse Bihi Abdi and his Hussein Abokor section of the Sa'ad Muuse sub-clan of the Habr Awal successfully liberated Hargeisa from the brutal communist regime and played a preeminent role for the SNM where they liberated Hargeisa, and Faraweyne. Simultaneously, the Isse Muuse Division commanded by Colonel Ibrahim Dhagaweyne liberated the strategic port city of Berbera and the historic town of Sheikh. After the establishment of Somaliland in 1991. Habr Awal businessmen funded the most money where they donated millions of dollars to provide SNM fighters with food, supplies and military grade equipment. The Habr Awal commercial cities like Berbera and Wajaale is where gained most of the weapons were imported through from and with the wealthy Habr Awal businessmen the SNM forces were able to gain enough weapons.[47]

The Habr Awal clan played a dominant role with SNM and were one of the respected founders. They also built Somaliland's political institutions from the ground under the consequential rule of Somaliland's 2nd president Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal. During his 9-year tenure as President of Somaliland, Egal managed to disarm local rebel groups, stabilized the northwestern Somaliland region's economy, and established informal trade ties with foreign countries. He also introduced the Somaliland shilling, passport and a newly redesigned flag. In addition, Egal created the Somaliland Armed Forces, the most effective Somali armed forces since the disbandment of the Somali National Army in 1991.[48]

List of prominent Habr Awal SNM Commanders (Mujahids).[49]

- Colonel Abdilahi Askar Barkhad

- Abdikarim Hashi Elmi

- Adan Dhamah

- Adan Shiine

- Ahmed Jama Sabban (Janan Oogo)

- Ahmed Mohamed Gulaid

- Ahmed Dhagah

- Ahmed Ibrahim (Raage Bidaar)

- Ahmed Golhaye

- Ahmed Mohamed Hasan (Ahmed Japan)

- Ali Gurey

- General Ali Hussein Abdi

- Boobe Yusuf Dualeh

- General Hassan Yonis Habane

- Haybe Ahmed Gure (Haybe Laambad)

- Hamud Ibrahim Ismail

- Professor Ibrahim Meygaag Samatar

- Ibrahim Dhagahweyne

- Sheikh Ibrahim Madar

- Mohamed Elmi Samatar Galan

- General Mohamed Hasan Abdullahi (Jidhif)

- Mohamed Hashi Elmi

- Mohamed Hasan (Gacmo Dheere)

- Mahdi Ali Farah

- Colonel Muse Bihi Abdi

- Sheikh Yusuf Ali Sheikh Madar

- Yahya Haji Ibrahim

Clan Tree and Lineage

In the Isaaq clan-family, component clans are divided into two uterine divisions, as shown in the genealogy. The first division is between those lineages descended from sons of Sheikh Ishaaq by a Harari woman – the Habr Habuusheed – and those descended from sons of Sheikh Ishaaq by a Somali woman of the Magaadle sub-clan of the Dir – the Habr Magaadle. Indeed, most of the largest clans of the clan-family are in fact uterine alliances hence the matronymic "Habr" which in archaic Somali means "mother".[50] This is illustrated in the following clan structure.[51] DNA analysis of Habr Awal clan members inhabiting Djibouti found that all of the individuals belonged to the EV32 subclade of the Y-DNA E1b1b paternal haplogroup.[52]

A summarized clan family tree of major Habr Awal subclans is presented below.[53]

- Sheikh Ishaaq Bin Ahmed Al Hashimi (Sheikh Ishaaq)

- Habr Habuusheed

- Ahmed (Tol-Ja’lo)

- Muuse (Habr Jeclo)

- Ibrahiim (Sanbuur)

- Muhammad (‘Ibraan)

- Habr Magaadle

- Ismail (Garhajis)

- Ayub

- Muhammad (Arap)

- Abdirahman (Habr Awal)

- Sa'ad Muuse

- Abdirahman Sa'ad

- Abdalla Sa'ad

- Hassan Sa'ad

- Abdalla Hassan

- Isaaq Sa'ad

- Makahil

- Nux Makahil

- Abokor Makahil

- Cumar Makahil

- Mohammed Makahil

- Hassan Makahil

- Ali Hassan

- Jibril Hassan

- Rooble Hassan

- Osman Hassan

- Mohammed Isaaq (Abbas)

- Isse Isaaq (Ciise Carab)

- Musa (Ase) Isaaq

- Yeesif Isaaq

- Abokor Isaaq

- Ugaadh Abokor (Ugaadhyahan)

- Abdalla Abokor

- Hussein Abokor

- Osman Hussein (Cismaannada)

- Jibril Hussein

- Ismail Jibril

- Nuh Ismail

- Yunis Nuh (Reer Yunis Nuh)

- Shirdoon Yonis (Reer Shirdoon)

- Hoosh Yonis (Reer Hoosh)

- Gadid Yonis (Reer Gadid)

- Mohammed Yonis

- Ahmed Nuh (Reer Ahmed Nuh)

- Yunis Nuh (Reer Yunis Nuh)

- Said Ismail

- Abdalla Said

- Samatar Abdalla (Reer Samatar)

- Abane Abdalla (Reer Abane)

- Ahmed Abdalla (Reer Ahmed Abdalla); The Sultan of Habr Awal's Royal Lineage [54]

- Abdalla Said

- Abdalla Ismail

- Ali Ismail

- Idris Ismail (Bah Gobo)

- Muhumed Ismail (Waran'ad)

- Yonis Ismail (Bah Gobo)

- Yusuf Ismail

- Nuh Ismail

- Ismail Jibril

- Jibril Abokor

- Adan Jibril (Bahaabar Adan)

- Ali Jibril

- Omar Ali

- Abeeb Omar (Baha Omar)

- Abtidon Omar (Baha Omar)

- Adan Omar

- Hussein Qawa Omar (Baha Omar)

- Sahal Omar (Baha Omar)

- Yonis Omar (Dugeh)

- Ismail Omar

- Barre Ismail

- Hareed Barre (Reer Hareed)

- Dalal Ismail (Reer Dalal)

- Geedi Ismail 'Gheedi Shide' (Baha Omar)

- Hoosh Ismail (Baha Omar)

- Higgis Ismail

- Idris Ismail

- Ollow Ismail

- Samatar Ismail

- Qayaad Ismail (Baha Omar)

- Barre Ismail

- Omar Ali

- Hassan Jibril

- Mohamed Jibril (Deriyahan)

- Yonis Jibril (Reer Yonis)

- Urkurag Yonis

- Adan Urkurag

- Omar Adan

- Ali Adan

- Ahmed Adan

- Adan Urkurag

- Urkurag Yonis

- Makahil

- Sa'ad Muuse

- Habr Habuusheed

- Issa Muuse

- Adan Issa

- Jibril Adan

- Mohamoud Jibril

- Hassan Jibril

- Ibrahim Jibril

- Ismail Jibril

- Jibril Adan

- Abokor Issa

- Hassan Abokor

- Balle Hassan (Reer Baale)

- Musa Hassan

- Hassan Abokor

- Idarys Issa

- Mohamed Issa

- Mukhtar Mohamed

- Hassan Mohamed

- Jibril Mohamed

- Omar Jibril

- Abokor Jibril

- Yonis Jibril

- Muuse Jibril

- Ali Muuse

- Sahal Ali (Reer Sahal)

- Wa'ays Ali (Reer Wa'ays)

- Abane Ali (Reer Abane)

- Had Ali (Reer Had)

- Hildid Ali (Reer Hildid)

- Ali Muuse

- Abdirahman Muuse

- Abdulle Muuse

- Abdalle Abdulle (Abdalle Qoyan)

- Hassan Abdulle

- Ahmed Hassan (Dhogori)

- Deriyahan Hassan

- Adan Issa

- Abdi Muuse

- Abdalla Muuse

- Afgab Muuse

- Egalle Muuse

- Eli Muuse

- Omar Muuse

- Issa Muuse

Prominent and Influential figures

The clan has produced some of the most prominent and influential Somali figures in history, who are listed below:

- Sultan Osman Sultan Ali Koshin, the current general sultan of the Issa Musse clans.

- Abdillahi Suldaan Mohammed Timacade, known as "Timacade", a famous poet during the pre- and post-colonial periods

- Abdulrahim Abby Farah, Under-Secretary-General of the United Nations 1979–1990 and Permanent Representative of Somali Republic to the United Nations 1965–1972.

- Abdurrahman Mahmoud Aidiid, He is the current Mayor of Hargeisa, the capital of the Republic of Somaliland.

- Abdishakur Iddin He is the current Mayor of Berbera capital of Sahil, Somaliland Region.

- Abdul Majid Hussein, Economist, Former Permanent Representative of Ethiopia to the United Nations, 2001-2004. Leader of Ethiopian Somali Democratic League (ESDL) party in the Somali Region of Ethiopia from 1995-2001.

- Ahmed Mohamed Gulaid, was one of the founding members of the Somali National Movement and was the first to be elected as the chairman of the organization in October 1981.

- Ahmad Girri bin Husain, Right hand partner of Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi (Ahmed Guray) and a high ranking Adal Sultanate general who lead a large army against the Abyssinian empire.[55]

- Ahmed Hassan Awke, Legendary Somali journalist and broadcaster. He was a veteran of the BBC World Service, the Voice of America, Somaliland National TV, Horn Cable Television, Radio Mogadishu and Universal TV among also being the presidential spokesman of Siad Barre during his Military Junta.[56]

- Ahmed Yusuf Yasin, was the Vice-President of Somaliland from 2002 until 2010. and The Second Chairman of UDUB party.

- Ali Abdi Farah, Former Minister of Communication and Culture in Djibouti

- Ali Feiruz, celebrated Somali musician in Djibouti and Somalia

- Gaarriye (born Mohamed Hashi Dhama), Famous poet who composed one of the best known Somali language poems on the theme of reconciliation, "Hagarlaawe" (The Charitable).

- Hussain Bisad, is one of the tallest men in the world, at 2.32 m (7 ft 7 1⁄2 in). He has the largest hand span of anyone alive.

- Ibrahim Dheere, Considered to be the first Somali billionaire and richest Somali person in the world with an estimated net worth of 1.8 billion US Dollars.[57]

- Ismail Ahmed, owner and CEO of WorldRemit which is one of the fastest growing money transfer company in the world and he's considered 7th most influential man in Britain.[58]

- Muhammad Haji Ibrahim Egal, Legendary Somali politician. First Prime Minister of Somalia: 1960, 1967–1969. President of Somaliland, 1993–2002.

- Mohammed Abdillahi Kahin 'Ogsadey', A Somali business tycoon based in Ethiopia, where he established MAO Harar Horse, the first African corporation to export coffee and amassed a net worth of approximately $3 Billion Ethiopian Birr.[59]

- Mohamed Abdullahi Omaar, former Foreign Minister of Somalia

- Mohamed Hasan Abdullahi, former Chief of Staff of Somaliland Armed Forces

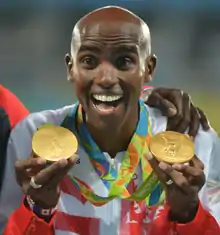

- Mo Farah, British four-time Olympic gold medalist and the most decorated athlete in British athletics history. He's also considered to be the best marathon runner in the world.[60]

- Abdi Haybe Laampad Veteran Somali comedian and one of the best Somali comedian of all time.

- Mohamed Omar Arte, former Deputy Prime Minister of Somalia.

- Muhammad Hawadle Madar, former Prime Minister of Somalia from September 3, 1990 to January 24, 1991.

- Muse Bihi Abdi, former military officer served as Somali Air Force Colonel and since December 2017. Current President Of Somaliland.

- Nuh Ismail Tani, current Chief of Staff of Somaliland Armed Forces

- Rageh Omaar, Somali-British journalist and writer; former BBC world affairs correspondent; moved to a new post at Al Jazeera English in 2006; as of 2017 is with ITV News

- Umar Arteh Ghalib, former Prime Minister of Somalia, 1991–1993; brought Somalia into the Arab League in 1974 during his term as Foreign Minister of Somalia, 1969-1977; former president of UN Security Council; teacher and poet

- Sheikh Madar Ahmed Shirwac, credited with the early growth of Hargeisa[61]

References

- Central Intelligence Agency (2002). "Ethnic Groups". Somalia Summary Map. Perry–Castañeda Library. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- Castagno, Margaret (1975). Historical dictionary of Somalia. ISBN 9780810808300.

- http://www.awdalpress.com/index/one-clan-domination-is-complete-in-somaliland/

- Renders, Marleen (2012-01-20). Consider Somaliland: State-Building with Traditional Leaders and Institutions. ISBN 9789004222540.

- Omaar, Rakiya; Waal, Alexander De; McGrath, Rae; (Organization), African Rights (1993). "Violent deeds live on: landmines in Somalia and Somaliland, p. 63". |

- http://www.unhcr.org/publ/RESEARCH/3d5d0f3a4.pdf/

- Imbert-Vier, Simon (2011). Tracer des frontières à Djibouti: des territoires et des hommes aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 9782811105068.

- Lewis, I. M. (1999). I. M. Lewis, A pastoral Democracy. ISBN 9780852552803.

- "مخطوطات > بهجة الزمان > الصفحة رقم 16". makhtota.ksu.edu.sa. Retrieved 2017-08-24.

- "Piece of Berbera History: Reer Ahmed Nuh Ismail". wordpress.com. 21 August 2015.

- Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 238.

- Ethnographic Survey of Africa, Volume 5. 1969. p. 24.

- British Somaliland, by Ralph Evelyn Drake-Brockman, p. 36

- Lewis, I.M. (1965). The Modern History of Somaliland: from Nation to State. Praeger. p. 35.

- Pankhurst, R. (1965). Journal of Ethiopian Studies Vol. 3, No. 1. Institute of Ethiopian Studies. p. 45.

- Hunter, Frederick (1877). An Account of the British Settlement of Aden in Arabia. Cengage Gale. p. 41.

- 'Twixt sirdar & Menelik: an account of a year's expedition from Zeila to Cairo, p. 18, 1901

- Somali Poetry, Lewis & Adrzejewski, 1964, pp. 111–115

- The Dublin Review, Volume 98. 1886. p. 176.

- Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. 9780226467917. p. 70. ISBN 9780226467917.

- Davies, Charles E. (1997). The Blood-red Arab Flag: An Investigation Into Qasimi Piracy, 1797-1820. University of Exeter Press. p. 167. ISBN 9780859895095.

- Pankhurst, Richard (1965). "The Trade of the Gulf of Aden Ports of Africa in the Early Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 3 (1): 36–81.

- Al Qasimi, Sultan bin Muhammad (1996). رسالة زعماء الصومال إلى الشيخ سلطان بن صقر القاسمي (in Arabic). p. ١٢.

- Laitin, David D. (1977). Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience. 9780226467917. p. 70. ISBN 9780226467917.

- D. J. Latham Brown (1956). "The Ethiopia-Somaliland Frontier Dispute". International and Comparative Law Quarterly. 5 (2): 245–264. doi:10.1093/iclqaj/5.2.245. JSTOR 755848.

- Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 53.

- British and Foreign State Papers. H.M. Stationery Office. 1893.

- Felix, Rosen (1907). Eine deutsche Gesandtschaft in Abessinien (in German). VERLAG VON VEIT & COMP Leipzig. p. 115. ISBN 9780274113415.

- Carlos-Swayne, Harald (1900). Seventeen Trips Through Somaliland and a Visit to Abyssinia. p. 138.

- Mainwaring, H.G (1894). A Soldier's Shikar Trips. Grant Richards Ltd. p. 77.

- Ram, Venkat (2009). Anglo-Ethiopian Relations, 1869 to 1906: A Study of British Policy in Ethiopia. Concept Publishing Company New Delhi. p. 121. ISBN 9788180696244.

- Felix, Rosen (1907). Eine deutsche Gesandtschaft in Abessinien (in German). VERLAG VON VEIT & COMP Leipzig. p. 115. ISBN 9780274113415.

- Felix, Rosen (1907). Eine deutsche Gesandtschaft in Abessinien (in German). VERLAG VON VEIT & COMP Leipzig. p. 115. ISBN 9780274113415.

- Felix, Rosen (1907). Eine deutsche Gesandtschaft in Abessinien (in German). VERLAG VON VEIT & COMP Leipzig. p. 115. ISBN 9780274113415.

- Great Britain, House of Commons (1901). Parliamentary Sessional Papers volume 48. HM Stationery Office. p. 5.

- Great Britain, House of Commons (1901). Parliamentary Sessional Papers volume 48. HM Stationery Office. p. 15.

- Milman, Brock (2013). British Somaliland: An Administrative History, 1920-1960. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 9780415717458.

- Milman, Brock (2013). British Somaliland: An Administrative History, 1920-1960. Routledge. p. 64. ISBN 9780415717458.

- Milman, Brock (2013). British Somaliland: An Administrative History, 1920-1960. Routledge. p. 79. ISBN 9780415717458.

- Orwin, Martin; Axmed, Rashiid (2009). War and Peace: An anthology of Somali literature Suugaanta Nabadda iyo Colaadda. Progressio. p. 206. ISBN 9781852873295.

- Orwin, Martin; Axmed, Rashiid (2009). War and Peace: An anthology of Somali literature Suugaanta Nabadda iyo Colaadda. Progressio. p. 206. ISBN 9781852873295.

- War and Peace: An Anthology of Somali literature, p.86

- Mohamed, Jama (2002). Imperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of Somaliland, 1954-1960. The English Historical Review.

- Mohamed, Jama (2002). Imperial Policies and Nationalism in The Decolonization of Somaliland, 1954-1960. The English Historical Review.

- Helen Chapin Metz, Somalia: a country study, Volume 550, Issues 86-993, (The Division: 1993), p.xxviii.

- Jama, Hassan Ali (2005). Hassan Ali Jama, Who cares about Somalia. ISBN 9783899300758.

- Lewis, I. M. (1983). Nationalism & Self determination in the Horn of Africa. ISBN 9780903729932.

- Glickman, Harvey (1995). Ethnic Conflict and Democritization in Afrcia, p. 217. ISBN 9780918456748.

- Forberg, Ekkehard; Terlinden, Ulf (13 April 1999). Small Arms in Somaliland: Their Role and Diffusion. BITS. ISBN 9783933111012 – via Google Books.

- Lewis, I. M.; Samatar, Said S. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. ISBN 9783825830847.

- I. M. Lewis, A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa, (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p. 157.

- Iacovacci, Giuseppe; et al. (2017). "Forensic data and microvariant sequence characterization of 27 Y-STR loci analyzed in four Eastern African countries". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 27: 123–131. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.12.015. PMID 28068531. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- http://isaaq.webs.com/habrawal.htm

- https://books.google.ca/books?id=Mu0MAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA248&lpg=PA248&dq=the+royal+race+is+the+ayyal&source=bl&ots=fvtY7ZzikW&sig=Nk4RnVjm_ZTcVcZKthn22tFUBKQ&hl=en&sa=X&ved=0ahUKEwi3kKnLsffZAhUCvVkKHWNiAiYQ6AEIJzAA#v=onepage&q=the%20royal%20race%20is%20the%20ayyal&f=false, Sir Richard Francis Burton, First Footsteps in East Africa, Or, An Exploration of Harar, Volume 2, p. 52.

- "مخطوطات > بهجة الزمان > الصفحة رقم 17". makhtota.ksu.edu.sa. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- http://www.somalilandinformer.com/somaliland/somaliland-prominent-somali-journalist-ahmed-hasan-awke-passes-away-in-jigjiga/

- http://www.somalilandinformer.com/somaliland/breaking-ibrahim-dheere-tycoon-passes-away-in-djibouti/

- https://www.worldremit.com/en/about-us/management-team

- "Somali Entrepreneurs". Salaan Media. 15 June 2017. Retrieved 15 Feb 2018.

- "Mo Farah's family cheers him on from Somaliland village". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- Abdurahman., A (2017). Making Sense of Somali History. Adonis and Abbey. p. 80.