Gadabuursi

The Gadabuursi (Somali: Gadabuursi, Arabic: غادابوورسي), also known as Samaroon (Arabic: قبيلة سَمَرُون), is a Somali clan, a sub-division of the Dir clan family.[1]

غادابورسي سمرون | |

|---|---|

The Tomb of Sheikh Samaroon | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Somali | |

| Religion | |

| Islam (Sunni, Sufism) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Issa, Surre, Biimaal, Gurgura, Bursuuk, other Dir clans, Isaaq, Hawiye and other Somali clans. Saho people(Gadafur) |

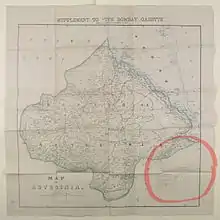

The Gadabuursi are geographically spread out across three countries: Ethiopia, Somaliland and Djibouti. Among all of the Gadabuursi inhabited regions of the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia is the country where the majority of the clan reside. In Ethiopia, the Gadabuursi are mainly found in the Somali Region, but they also inhabit the Harar, Oromia and Afar regions.[2][3][4]

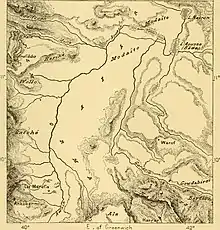

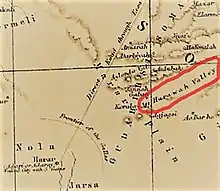

In Somaliland, the Gadabuursi are the predominant clan of the Awdal Region.[5][6] They are mainly found in cities and towns such as Borama, Baki, Lughaya, Zeila, Dilla, Jarahorato, Amud, Abasa, Fiqi Aadan, Quljeed, Boon and Harirad.[7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15] In Ethiopia, the Gadabuursi are the predominant clan of the Awbare district in the Fafan Zone, the Dembel district in the Sitti Zone and the Harrawa Valley.[16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23] They are mainly found in cities and towns such as Awbare, Awbube, Sheder, Lefe Isa, Derwernache, Gogti, Jaare, Heregel, Arabi and Dembel.[16][24][18][25][26][27]

The etymology of the name Gadabuursi, as described by writer Ferrand in Ethnographic Survey of Africa refers to Gada meaning people and Bur meaning mountain, hence Gadabuursi is believed to mean people of the mountains.[28][29]

Overview

As a Dir sub-clan, the Gadabuursi have immediate lineal ties with the Issa, the Surre (Abdalle and Qubeys), the Biimaal (who the Gaadsen also belong to), the Bajimal, the Bursuk, the Madigan Dir, the Gurgura, the Garre (the Quranyow sub-clan to be precise as they claim descent from Dir), Gurre, Gariire, other Dir sub-clans and they have lineal ties with the Hawiye (Irir), Hawadle, Ajuraan, Degoodi, Gaalje'el clan groups, who share the same ancestor Samaale.[30][31][32][33][34][35][36] The patriarch Samaale arrived in Somaliland from Yemen during the 9th century and subsequently founded the eponymous Samaale clan.[37] Dir traces descent from Irir the son of Samaale, who in turn traces his genealogical traditions to Arabian Quraysh Banu Hashim origins through Aqiil the son of Abu Talib ibn Abd al-Muttalib, who was cousin of the Prophet Muhammed.[38][39][40][41][42][43]

Most Gadabuursi members are descendants of Sheikh Samaroon. However, Samaroon does not necessarily mean Gadabuursi, but rather represents only a sub-clan of the Gadabuursi clan family.

The Gadabuursi in particular, is the only clan with a longstanding institution of Sultan. The Gadabuursi use the title Ugaas which means sultan and/or king. Ughaz or Ugas.[44][45]

Based on research done by the Eritrean author 'Abdulkader Saleh Mohammad' in his book 'The Saho of Eritrea, the Saho people (Gadafur) is said to have Somali origins from the Gadabuursi.[46]

Distribution

The Gadabuursi are mainly found in northwestern Somalia and are the predominant clan of the Awdal region.[5][47][48]

Federico Battera (2005) states about the Awdal Region:

"Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans."[49]

A UN Report published by Canada: Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (1999), states concerning Awdal:

"The Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs."[50]

Marleen Renders and Ulf Terlinden (2010) both state that the Gadabuursi almost exclusively inhabit the Awdal Region:

Awdal in western Somaliland is situated between Djibouti, Ethiopia and the Issaq-populated mainland of Somaliland. It is primarily inhabited by the three sub-clans of the Gadabursi clan, whose traditional institutions survived the colonial period, Somali statehood and the war in good shape, remaining functionally intact and highly relevant to public security.[51]

The Gadabuursi also partially inhabit the neighboring region of Woqooyi Galbeed, and reside in many cities within that province.[52][53] The Gadabuursi are the second largest clan by population in Somaliland.[54] Within Somalia, they are known to be the 5th largest clan.[55]

The Gadabuursi are also found in Djibouti, where they form one of the major clan groups.[56] Within Djibouti they have historically lived in 2 of the 7 major neighborhoods in Djibouti (Quarter 4 and 5).[57]

However the majority of the Gadabuursi inhabit the Somali Region of Ethiopia.[53][58][59]

Federico Battera (2005) states:

But most of the Gadabuursi inhabit the Somali Region of Ethiopia (the so-called region five) where their paramount king, (the Ugaas) resides...[60] In present day Awdal, most of the prominent elders have their main venues in the capital city of the region, Borama. However, the paramount king of the Gadabuursi, the Ugaas, has his main venue in Ethiopia.[61]

In the Somali Region of Ethiopia, the Gadabuursi exclusively inhabit both the Awbare district in the Fafan Zone and the Dembel district in the Sitti Zone.[62][63] The Gadabuursi also exclusively inhabit the Harrawa Valley which is considered to be traditional Gadabuursi territory.[20][21][22][16][64][15]

The Department of Sociology and Social Administration, Addis Ababa University, Vol. 1 (1994), describes the Awbare district as being predominantly Gadabuursi. The journal states:

Different aid groups were also set up to help communities cope in the predominantly Gadabursi district of Aw Bare.[17]

Filipo Ambrosio (1994) describes the Awbare district as being predominantly Gadabuursi whilst highlighting the neutral role that they played in mediating peace between the Geri and Jarso:

The Gadabursi, who dominate the adjacent Awbare district north of Jijiga and bordering with the Awdal Region of Somaliland, have opened the already existing camps of Derwanache and Teferi Ber to these two communities.[18]

Filipo Ambrosio (1994) highlights how the Geri and Jarso both sought refuge on adjacent Gadabuursi clan territory after a series of conflicts broke out between the two communities in the early 1990s:

Jarso and Geri then sought refuge on 'neutral' adjacent Gadabursi territory in Heregel, Jarre and Lefeisa.[25]

The Research-inspired Policy and Practice Learning in Ethiopia and the Nile region (2010) states that the Dembel district is predominantly Gadabuursi:

Mainly Somali Gurgura, Gadabursi and Hawiye groups, who inhabit Erer, Dambal and Meiso districts respectively.[65]

Richard Francis Burton (1856) describes the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabuursi country, as within sight of Harar:

In front, backed by the dark hills of Harar, lay the Harawwah valley.[15]

Captain H.G.C Swayne R.E. (1895) describes the Harrawa Valley as traditional Gadabuursi territory:

On 5 September we descended into the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabursi country, and back on to the high ban again at Sarír, four days later. We then marched along the base of the Harar Highlands, reaching Sala Asseleh on 13 September. We had experienced heavy thunder-storms with deluges of rain daily, and had found the whole country deserted.[21]

Captain H.G.C Swayne R.E. (1895) describes the Harrawa Valley as occupying an important strategic position in the Gadabuursi country:

The position of the Samawé ruins would favour a supposition that some power holding Harar, and having its northern boundary along the hills which wall in the southern side of the Harrawa valley, had built the fort to command the Gáwa Pass, which is one of the great routes from the Gadabursi country up on to the Marar Prairie.[22]

Richard Francis Burton describes the Gadabuursi and Geri Somali clans as extending to within sight of Harar.[66] The Gadabuursi, along with the Geri, Issa and Karanle Hawiye represent the most native and indigenous Somali tribes in Harar.[67][68][69]

The Gadabuursi inhabit the Gursum woreda where they are the majority and the Jijiga woreda where they make up a large part of the Fafan Zone. They partially inhabit Ayesha, Shinile, Erer and Afdem woreda's.[70][71][72]

The Gadabuursi also reside along the northeastern fringe of the chartered city-state of Dire Dawa, which borders the Dembel district, but also in the city itself.[63][73] The Gadabuursi are the second largest sub-clan within the borders of the Somali Region of Ethiopia based on the Ethiopian population census.[74] The 2014 Summary and Statistical report of the Population and Housing Census of the Federal Republic of Ethiopia has shown that Awbare is the most populated district in the Somali Region of Ethiopia.[74]

The Gadabuursi of Ethiopia have also expressed a desire to combine the clan's traditional territories to form a new region-state called Harawo State.[75]

Saho people

The Saho (sometimes called Soho) are an ethnic inhabiting the Horn of Africa.[76] They are principally concentrated in Eritrea, with some also living in adjacent parts of Ethiopia. They speak Saho, (which is related to Somali) as a mother tongue.[77]

Among the Saho there is a saintly clan, the Gadafur. When it comes to customary law of the Saho, the Gadafur, who are considered part of the holy families, act as religious leaders and political mediators of the Minifere tribes. The Gadafur have a high status and are highly privileged and respected among the Saho. It is said that the Gadafur are originally from the tribe of Gadabuursi[78]

History

Medieval Age

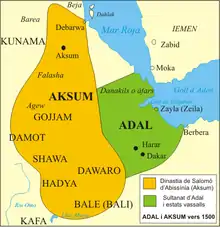

"I.M. Lewis gives an invaluable reference to an Arabic Manuscript on the history of to the Gadabuursi Somal. "This Chronicle opens", Lewis tells us, 'with an account of the wars of Imam 'Ali Si’id (1392), from whom the Gadabuursi today trace their descent, and who is described as the only Muslim leader fighting on the western flank in the armies of Se’ad ad-Din, ruler of Zeila.' Se’ad ad-Din was the joint founder of the Kingdom of Adal along with his brother Haqedin II." So not only did the Gadabuursi clan contribute to the Adal Wars, Conquest of Abyssinia, but their predecessors were also fighting wars way before the establishment of the Adal Sultanate.[79] The descendants praise and sing his hymns and make their pilgrimages to his local shrine at Tukali to commemorate their ancestor. The largest portion of the Gadabursi reside in the borders of Ethiopia. It is said that at Waraf, a location near Hardo Galle a great battle took place between the Gadabuursi and infidels (Galla) in the 14th century according to traditional Gadabursi history[80][81]

The Gadabursi Kingdom was established more than 600 years ago, and consisted of a King (Ugaas) and many elders.

Hundreds of elders used to work in four sections consisting of 25 elders each:

- Social committee

- Defense – policing authorities consisting of horsemen (referred to as fardoolay), foot soldiers and spear-men, but also askaris or soldiers equipped with poison arrows.[82]

- Economy and collection of taxes

- Justice committee

The chairmen of the four sections were called Afarta Dhadhaar, and were selected according to talent and personal abilities.

A constitution, Xeer Gadabursi, had been developed, which divided every case as to whether it was new or had precedents (ugub or curad).

The Gadabursi King and the elders opposed the arrival of the British at the turn of the twentieth century, but they ended up signing an agreement with them. Later, as a disagreement between the two parties both arose and intensified, the British installed some people against the Ugaas in hopes of overthrowing him. This would eventually bring about the collapse of the kingdom.

'The Law of the King and the 100 Men "Heerka Boqorka iyo Boqolka Nin"'

"When a new Ugaas or Ughaz was appointed amongst the Gadabuursi, a hundred elders, representatives of all the lineages of the clan, assembled to form a parliament to promulgate new heer agreements, and to decide what legislation they wished to retain from the reign of the previous Ugaas or King. The compensation rates for delicts committed within the clan were revised if necessary, and a corpus of Gadabuursi law, as it were, placed on the statutes for the duration of the new Ugaas's rule.

This was called 'the law of the King and the 100 men' (heerka boqorka iyo boqolka nin).[83]

The Gadabuursi Ugaas used to host equestrian games for 100 men in the Harrawa (Harar) Valley, a valley in the Somali region of Ethiopia, situated North-East from Harar. As quoted:

Here, probably to commemorate the westward progress of the tribe, the Gadabuursi Ugaz or King has the white canvass turban bound about his brows, and hence rides forth to witness the equestrian games in the Harawwah Valley.[15]

Traditional Gadabuursi installation ceremony

Here are accounts of a traditional Gadabuursi installation ceremony by accounts of Sheikh 'Abdurahman Sh. Nur in "A Pastoral Democracy", by I'M Lewis.[84]

The pastoral Somali have few large ceremonies and little ritual. for its interest, therefore I reproduce here a summary of a very full account of traditional Gadabuursi installation ceremony given me by Sheikh 'Abdurahman Sheikh Nur, the present governor kadi of Borama, God bless his soul. Clansmen gather for the ceremony in well wooded and watered place. There is singing and dancing, then stock are slaughtered for feasting and sacrifice. The stars are carefully watched to determine a propitious time and then future Ughaz is chosen by divination. Candidates must be sons or brothers of the former Ughaz and the issue of woman who has been only married once. She should not be a woman who has been divorced or a widow. Early on a monday morning a man of the Rer Nur (the laandeer of the Gadabuursi) plucks a flower or leaf and throws it upon the Ughaz. Everyone else then follows his example. The man who starts the 'aleemasaar acclamation must be a man rich in livestock, with four wives and many sons. Men of the Mahad Muuse lineage then brings four vessels of milk. One contains camels' milk, one cows' milk, one sheep's milk and the last goats' milk. These are offered to the Ughaz who selects one and drinks a little from it. If he drinks the camels' milk, camels will be blessed and prosper, if he drinks the goats' milk, goats will prosper, and so on. After this, a large four-year-old ram is slaughtered in front of him. His hair is cut by a man of the Gadabuursi and he casts off his old clothes and dons new clothes as Ughaz. A man of Rer Yunis puts a white turban round his head and his old clothes are carried off by men of the Jibra'iin. The Ughaz then mounts his best horse and rides to a well called bugay, near garis, towards the coast. The well contains deliciously fresh water. Above the well are white pebbles and on these he sits. He is washed by a brother or other close kinsman as he sits on top of the stones. Then he returns to the assembled people and is again acclaimed and crowned with leaves. dancing and feasting recommence. The Ughaz makes a speech in which he blesses his people and asks god to grant peace, abundant milk and rain- all symbols of peace and prosperity (nabad iyo 'aano). If rain falls after this, people will know that his reign will be prosperous. That the ceremony is customarily performed during the karan rainy season makes this all more likely. The Ughaz is given a new house with entirely new effects and furnishings and a bride is sought for him. She must be of good family, and the child of a woman who has had only one husband. Her bride-wealth is paid by all the Gadabuursi collectively, as they thus ensure for themselves successors to the title. Rifles or other fire-arms are not included in the bride-wealth. Everything connected with accession must be peaceful and propitious

Ethiopia

According to a Max Planck research paper, one branch of the Ughaz family (Reer Ugaas) on the borders of Ethiopia rose to the rank of Dejazmach (ደጃዝማች ) or 'Commander of the Gate' .[85] A military title meaning commander of the central body of a traditional Ethiopian armed force composed of a vanguard, main body, left and right wings and a rear body.[4]

Djibouti

The Gadabuursi are the pioneers of the name Cote Francaise des Somali or the French Somali coast. Haji Dideh, the Sultan of Zeila and prosperous merchant coined the name to the French. He also built the first mosque in Djibouti.[86][87][88] Before the French aligned with the Issa's the Gadabuursi were also the first Senator of the country and first Somalis head of state to lead the territory compromising Djibouti today. Djama Ali Moussa a sailor pursued his political aspirations and managed to become the first Somali democratically elected head of state.[89][90]

Ambassadorial Brothers

The Ambassadorial Brothers were 3 brothers from a prominent family in the Horn of Africa.

It consisted of :

who were all descendants of Sheikh Hassan Nuriye and part of the Rer Ughaz, Makahil section of Gadabuursi.

Sheikhs Hassan Nuriye in turn was a descendant of Mohamed Gele Ughaz Roble I (The First). He was a famous sheikh in Somalia, Ethiopia and Djibouti, especially in Ethiopia concentrated around Dire Dawa and Harar.

Eventually he returned to Awbarre, his hometown and died there. He is buried in the town of Awbarre next to Sheikh Awbarre. His sons came to be known as the ambassadorial brothers. The first prominent Somali or even African family to have 3 individuals who are directly related to each other as brothers serving as ambassadors for 3 different neighboring countries.[91][92][93]

| Sheikh Hassan Nuriye | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mohamed | Ismail | Aden | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mohamed Osman Omar, The road to zero: Somalia's self-destruction

Balwo and Heello: Modern Somali Music

Somali modern music began with the balwo style, pioneered by Abdi Sinimo, who rose to fame in the early 1940s.[94][95][96] Abdi's innovation and passion for music revolutionized Somali music forever.[97] Its lyrical contents often deal with love, affection and passion. The Balwo genre was a forerunner to the Heello genre. Abdi Sinimo hailed from the North Western Regions of Somalia and Djibouti, more precisely the Rer Nur section of the Gadabuursi.[98][99][100] Modern sung Somali Poetry was introduced in the Heelo genre which is a form of Somali sung poetry. The Balwo name changed to Heello because of religious reasons. The earliest composers began their songs with Balwooy, Balwooy hoy Balwooy... but because of the negative connotation added to Balwo and the word implicating calamity in Arabic the Balwo was changed to Heello and thus the first bars of songs began with Heelloy, Heellelloy.[101]

See also:

Rooble Afdeeb (Roble Afdeb)

Roble Afdeb was a famous Somali warrior and poet from the North Western part of Somalia and Djibouti. Known to have pillaged and raided many Issa settlements. The poet and warrior is a legend in Somali history and he is highly renown for his bravery and gained fame not through anti-colonialism or Islamic devotion, but clan rivalry.

For more about Rooble Afdeeb visit the following:

Cali Bucul (Ali Bu'ul)

Ali Bu'ul was a famous Somali military leader and poet from the Western Somali regions, today within the borders of the Somali region of Ethiopia, known for his short lined poems (geeraar), compared to the long lines of gabay. Geeraar are traditionally recited on top of horse during times of battle and war. Many of the most well known ones came from his tongue and are still known today. He is also known to have battled the Somali religious leader in poetry named Mahamed Abdullah Hassan and coined the word Guulwade. Some of his famous works are Gammaan waa magac guud ( Horse is a general term), Guulside (Victory-Bearer) and Amaan Faras (In Praise of My Horse). His poems were also written in the Gadabuursi script. An extract of a geeraar Amaan Faras featured in the image below to illustrate Ali Bu'uls work written in the script.[102][103][104][105]

For more about Ali Bu'ul visit the following:

_Poem.jpg.webp)

The image below translates as:[106]

From the seaside of Bulahar, to the corner of the Almis mountain, and Harawe of the pools, Hargeisa of the Gob trees, My horse reaches all that in one afternoon, Is it not like a scuddling cloud? From it's pen, A huge roar is heard, Is it not like a lion leading a pride? In the open plains It makes the camels kneel down, Is it not like an exper camel-rustler? It's mane and tail has white tufts on the top, Is it not as beautiful as a galool tree abloom?

— Ali Bu'ul (Cali Bucul), In Praise of My Horse

Geography

Many travelers have visited the Gadabuursi country and described it in many ways. One of such travelers is Alfred Pease in the late 19th century he described the Gadabuursi country to be the most beautiful out of all Somali areas he visited:

No part of Somaliland that I have visited is more beautiful than this tract of country, watered by an almost perennial stream, now lined with great trees festooned with the armo creeper, now with the high green elephant grass or luxuriant jungles, and guarded by woody and rocky mountains on the left hand and on the right. Between the Tug or Wady and these hills the, country had a park-like appearance, with its open glades and grassy plains. But the new and varied vegetation of Africa was not the only object delightful to the eye: countless varieties of birds, hawks, buzzards, Batteleur and larger eagles, vultures, dobie birds, golden orioles, parrots, paroquets, the exquisite Somali starlings, doves of all sorts and sizes, small and great honey-birds, hoopoes, jays, green pigeons, great flocks of Guinea fowl, partridges, sand grouse, were ever to be seen on every hand, and, while the bush teemed with Waller's gazelle and dik-diks, the plains with Scemmerring's antelope, with a sprinkling of oryx, our road up the Tug was constantly crossed by the tracks of lions, elephants, leopards, the ubiquitous hvsena, and other wild beasts.

Gadabuursi Ughazate

The royal family of the Gadabuursi, the Ugasate, evolved from and is a successor kingdom to the Sultanate of Harar and Adal Sultanate.[107] The first Ugaas of this break away and successor kingdom, Ali Makail Dera (Cali Makayl-Dheere) was the son of the progenitor of the Makayl-Dheere.[108] The matrilineal founder who established the Kingdom was Lady Khadija Sheikh Abba Yonis Hasan, from the Geri Koombe clan of the Darod clan.[109][110]

The Gadabuursi give their King the title of Ughaz.[111] It's an authentic Somali term for King or Sultan. The Gadabuursi in particular is the only clan with a longstanding tradition of having a Sultan.[44]

The first Ughaz of the Gadabuursi was Ughaz Ali Makail Dera (Cali Makayl-Dheere), who is the progenitor of the Reer Ugaas subclan to which the royal lineage belongs.

Ughaz Ali Makail Dera (Cali Makayl-Dheere) based on an Arabic manuscript on the Gadabuursi is said to be born in 1575 in Dobo, an area north of the present town of Borama in western Somaliland. He is recorded as having inflicted a heavy defeat on Galla forces at Nabadid.

Ughaz Nur I (the first) is said to have married the daughter of King Aale Boore after his defeat. Her name was Faaye Aale Boore. Ughaz Nur the first and Faaye Aale Boore gave birth Shirdoon, he was the 7th in line after Ughaz Hiraab. Aale Boore was a famous Oromo king, the victory of the former on the latter, marked a historical turning point in concluding the Oromo predominance.

Also the Gadabuursi managed to kill the next Oromo King after Aale Boore during the reign of Ughaz Roble I (Ugaas Rooble Ugaas Samatar), the first . It is said that during his reign the Gadabuursi tribe reached great influence and tremendous height in the region, having managed to defeat the reigning Galla/Oromo King at that time, whose name was Nuuno struck a blow to the Galla's their morale, their much loved king being killed. He was defeated by Geedi Bahdoon, also known as Geedi Malable. He struck a spear right through the King while he was in front of a tree, the spear pierced inside the tree making it not able for the King to escape or remove the spear. After he died he was buried in an area that's now called Qabri Nuuno near Sheedheer. In the picture already shared titled 'An old map featuring the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabuursi country, north of Harar' one can read Gabri Nono, which is the anglicized version of the Somali Qabri Nuuno.[112][108]

Ughaz Roble I died in 1848 and was buried in an area called Dhehror (Dhexroor) . It has become the custom for Somalis after Ughaz Roble I that whenever an Ughaz gets inaugurated and it rains, he should be named Ughaz Roble, which translates to the one with rain or rainmaker.

Ughaz Nur II (the second) was born in Zayla in the year 1835 and crowned in Bagi in 1848.[113] He established strong links with the Egyptian Khedive and Abdallah II ibn Ali of Harrar, during his reign the Western powers were vying for power in the Horn of Africa. He was also a great and famous poet. He was the type to speak words which would never be forgotten once they entered people's ears. He has created many poems and saying of which really explain the politics and knowledge of that time. How through patience and clever dealing one could be able to entrap one's enemy. He also used to say that whenever he heard a poem he would never forget it. His work was and is still taught in Somali Poetry classes (Suugaan: Fasalka Koobaad) among other Somali poets.[114][115]

For more about Ughaz Nur II visit the following:

For more about Ughaz 'Elmi Warfaa, visit the following:

.png.webp)

| Name | Reign

From |

Reign

Till |

Born | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ughaz Ali Makail Dera | 1607 | 1639 | 1575[112] |

| 2 | Ughaz Abdi I Ughaz Ali Makail Dera | 1639 | 1664 | |

| 3 | Ughaz Husein Ughaz Abdi Ughaz Ali | 1664 | 1665 | |

| 4 | Ughaz Abdillah Ughaz Abdi Ughaz Ali | 1665 | 1698 | |

| 5 | Ughaz Nur I Ughaz Abdi Ughaz Ali | 1698 | 1733 | |

| 6 | Ughaz Hirab Ughaz Nur Ughaz Abdi | 1733 | 1750 | |

| 7 | Ughaz Shirdon Ughaz Nur Ughaz Abdi | 1750 | 1772 | |

| 8 | Ughaz Samatar Ughaz Shirdon Ughaz Nur | 1772 | 1812 | |

| 9 | Ughaz Guleid Ughaz Samatar Ughaz Shirdon | 1812 | 1817 | |

| 10 | Ughaz Roble I Ughaz Samatar Ughaz Shirdon | 1817 | 1848 | |

| 11 | Ughaz Nur II Ughaz Roble Ughaz Samatar | 1848 | 1888 | 1828 |

| 12 | Ughaz Roble II Ughaz Nur Ughaz Roble | 1888 | 1898 | |

| 13 | Ughaz Olmi-Warfa "Olmi-Dheire" Ughaz Roble Ughaz Samatar | 1898 | 1938 | 1835[116] |

| 14 | Ughaz Abdi II Ughaz Roble Ughaz Nur | 1938 | 1948 | |

| 15 | Ughaz Dodi Ughaz Abdi Ughaz Roble | 1948 | 1952 | |

| 16 | Ughaz Roble III Ughaz Dodi Ughaz Roble | 1952 | 1977 | |

| 17 | Ughaz Jama Muhumed Ughaz Olmi-Warfa | 1960 | 1985 | |

| 18 | Ughaz Abdirashid Ughaz Roble Ughaz Dodi | 1985 | -[117] |

Currently Abdirashid is the Ughaz of the Gadabuursi.

Y-DNA

DNA analysis of Dir clan members inhabiting Djibouti found that all of the individuals belonged to the Y-DNA T1 paternal haplogroup.[118] All genetic analysis carried out on Gadabuursi male clan members have so far shown that they exclusively belong to the T1 paternal haplogroup.[119][120][121] A notable member of the T1 haplogroup is also the third US president, Thomas Jefferson.[122]

Clan tree

The Gadabursi clan according to many sources are divided into 2 divisions, the Habar Makadur and Habar 'Affan.

The Habar Makadur and Habar 'Affan, both historically united under a common Sultan or Ughaz.[30][123][124]

- Gadabursi

- Habar Makadur (Makadoor)

- Makahil

- 'Eli

- 'Iye

- 'Abdalle (Bahabar 'Abdalle)

- Hassan (Bahabar Hassan)

- Muse

- Makail Dera (Makayl-Dheere)

- Afgudud (Gibril Muse)

- Habr Sanayo

- Younis (Reer Yoonis)

- 'Ali Younis

- Jibril Younis (Jibriil Yoonis)

- Adan Younis (Aadan Yoonis)

- Nur Younis (Reer Nuur)

- Mahad 'Ase

- Bahabar Abokor

- Bahabar Muse

- Habr Musa

- Bahabar Aden

- Bababar 'Eli

- Reer Mohamed

- Abrahim (Abrayn)

- Habar 'Affan

- Jibrain

- Ali Ganun

- Gobe

- Habar Yusif

- Reer issa

- Hebjire

- Reer Zuber

- Dhega Wayne

- Makayl

- Musa

- Musafin

- Hassan Sá'ad

- Farole

- Reer Hamud

- Musa

- Makahil

- Habar Makadur (Makadoor)

The following listing is taken from the World Bank's Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics from 2005 and the United Kingdom's Home Office publication, Somalia Assessment 2001.[125][126]

Notable figures

- Aden Sh. Hassan, prominent Somali diplomat and ambassador of Djibouti, part of the 3 ambassadorial brothers of the Horn of Africa.

- Mohamed Sh. Hassan, prominent Somali diplomat and ambassador of Somalia, part of the 3 ambassadorial brothers of the Horn of Africa.

- Ismail Sh. Hassan, prominent Somali diplomat and ambassador of Ethiopia, part of the 3 ambassadorial brothers of the Horn of Africa.

- Ali Bu'ul, famous Somali poet from the 19th century, known for his geeraar's (short styled Somali poems recited during battles and wars)

- Roble Afdeb, famous legendary Somali warrior and poet, remembered for his bravery and clan-rivalry.

- Mohamed Farah Abdullahi (Hansharo), leader of Somali Democratic Alliance (f. 1989)

- Aden Isaq Ahmed, Minister and Politician of the Somali Republic

- Ahmed Gurey, the Conqueror of Abyssinia, the Imam of Adal Empire.

- Col. Muse Rabile Ghod, a Somali military leader and statesman of the Somali Democratic Republic.

- Yuusuf Talan, General of the Somali National Army.

- Djama Ali Moussa. First Senator of Djibouti or French Somaliland

- Ato Hussein Ismail. Ethiopian long-serving Statesman and first Somali to become a member of the Ethiopian Parliament

- Abdirahman Aw Ali Farah, first Somaliland Vice President, 1993–1997.[127]

- Mawlid Hayir, current Vice-president and minister of education and former governor of Jigjiga zone of the Somali region of Ethiopia.[128][129]

- Haji Ibrahim Nur, minister, merchant and politician of former British Somaliland Protectorate

- Hibo Nuura, Somali singer

- Abdi Hassan Buni, politician, minister of British Somaliland and first deputy prime minister of the Somali Republic.

- Abdi Ismail Samatar, Somali scholar, writer and professor.

- Ahmed Ismail Samatar, Somali writer, professor and former dean of the Institute for Global Citizenship at Macalester College. Editor of Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies

- Abdirahman Beyle, former Foreign Affairs Minister of Somalia an economist[130]

- Abdisalam Omer, Foreign Affairs Minister of Somalia; former Governor of the Central Bank of Somalia[131]

- Sheikh 'Abdurahman Sh. Nur, religious leader, qādi and the inventor of the Borama script.[132]

- Dahir Rayale Kahin, third President of Somaliland

- Ahmed Gerri of the Habar Maqdi(Makadi)/Makadur of the Conquest of Abyssinia[133][134]

- Sultan Dideh, sultan of Zeila, prosperous merchant and built first mosque in Djibouti. He also proposed the name "Cote francaise des Somalis" to the French[56][135][136]

- Yussur Abrar, former governor of the Central Bank of Somalia.[137]

- Ughaz Nur II, 11th Malak(King) of the Gadabursi.[138]

- Ughaz 'Elmi Warfa, 13th Malak(King) of the Gadabursi.

- Ato Shemsedin, Somali Ethiopian Politician, previous Ethiopian ambassador to Djibouti, Kenya, Deputy Minister of Mining and Energy and first Vice Chairman and one of the founders of ESDL[139][140]

- Ayanle Souleiman, Djiboutian athlete

- Hassan Mead, American distance runner, 2016 Olympic Men's 5000m finalist

- Abdirahman Sayli'i, current Vice-president of Somaliland[141]

- Ahmed Mumin Seed, Somaliland Minister of Agriculture

- Abdi Sinimo, a Somali singer and songwriter, noted for having established the balwo genre of Somali music.

- Hassan Sheikh Mumin, author of Shabeel Naagood or (Leopard among the Women)

- Khadija Qalanjo, a popular Somali singer

- Suleiman Ahmed Guleid, President of Amoud University

- Omar Osman Rabeh, Somali scholar, writer, professor, politician and pan-Somalist.

- Barkhad Awale Adan, Somali journalist and director of Radio Hurma

References

- Verdier, Isabelle (31 May 1997). Ethiopia: the top 100 people. Indigo Publications. p. 13. ISBN 9782905760128.

- Dostal, Walter; Kraus, Wolfgang (22 April 2005). Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. I.B.Tauris. p. 296. ISBN 9780857716774.

- "Somalia: The Myth of Clan-Based Statehood". Somalia Watch. 7 December 2002. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Samatar, Abdi I. (2001) "Somali Reconstruction and Local Initiative: Amoud University," Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies: Vol. 1, Article 9, p. 132.

- Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans. The Gadaabursi are concentrated in Awdal.

- Ciabarri, Luca. Dopo lo Stato. Storia e antropologia della ricomposizione sociale nella Somalia settentrionale: Storia e antropologia della ricomposizione sociale nella Somalia settentrionale (in Italian). FrancoAngeli. p. 258.

Baki region, the traditional region of the Gadabursi

- Ambroso, Guido (August 2002). Pastoral society and transnational refugees: population movements in Somaliland and eastern Ethiopia. UNHCR Brussels.

Chart showing the Gadabursi exclusively inhabiting the Baki district

- "An Ecological Assessment of the Coastal Plains of North Western Somalia (Somaliland)" (PDF). 2000. p. 11.

In the centre of the study area are the Gadabursi, who extend from the coastal plains around Lughaye, through the Baki and Borama districts into the Ethiopian highlands west of Jijiga.

- "RUIN AND RENEWAL: THE STORY OF SOMALILAND". 2004.

So too is the boundary of Lughaya district whose predominant (if not exclusive) inhabitants are today Gadabursi.

- ʻArabfaqīh, Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn ʻAbd al-Qādir (1 January 2003). The conquest of Abyssinia: 16th century. Hollywood: Tsehai Publishers & Distributors. ISBN 0-9723172-6-0.

- Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 9781135751753.

The major town of the Rer Mohamoud Nur, Dila.

- Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 9781135751753.

The Gadabuursi Reer Mahammad Nuur, for example, are said to have begun cultivating in 1911 at Jara Horoto to the east of the present town of Borama.

- Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. ISBN 9781135751753.

- Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 136. ISBN 9781135751753.

- "Sociology Ethnology Bulletin of Addis Ababa University". 1994.

Different aid groups were also set up to help communities cope in the predominantly Gadabursi district of Aw Bare.

- "Theoretical and Practical Conflict Rehabilitation in the Somali Region of Ethiopia". 2018–2019. p. 8.

The Gadabursi, who dominate the adjacent Awbare district north of Jijiga and bordering with the Awdal Region of Somaliland, have opened the already existing camps of Derwanache and Teferi Ber to these two communities.

- "Research-inspired Policy and Practice Learning in Ethiopia and the Nile region: Water and livelihoods in a highland to lowland transect in eastern Ethiopia" (PDF). 2010. p. 9.

mainly Somali Gurgura, Gadabursi and Hawiye groups, who inhabit Erer, Dambal and Meiso districts respectively.

- Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

In front, backed by the dark hills of Harar, lay the Harawwah valley. The breadth is about fifteen miles: it runs from south-west to north-east, between the Highlands of the Girhi and the rolling ground of the Gudabirsi Somal, as far, it is said, as the Dankali country. Of old this luxuriant waste belonged to the former tribe; about twelve years ago it was taken from them by the Gudabirsi, who carried off at the same time thirty cows, forty camels, and between three and four hundred sheep and goats.

- Swayne (1895). Seventeen Trips Through Somaliland.

On 5 September we descended into the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabursi country, and back on to the high ban again at Sarír, four days later. We then marched along the base of the Harar Highlands, reaching Sala Asseleh on 13 September. We had experienced heavy thunder-storms with deluges of rain daily, and had found the whole country deserted.

- Swayne (1895). Seventeen Trips Through Somaliland.

The position of the Samawé ruins would favour a supposition that some power holding Harar, and having its northern boundary along the hills which wall in the southern side of the Harrawa valley, had built the fort to command the Gáwa Pass, which is one of the great routes from the Gadabursi country up on to the Marar Prairie.

- Swayne (1895). Seventeen Trips Through Somaliland.

The extreme north-western angle of the Marar Prairie is marked by a hill called Sarir Gerad, and from its base the ground falls abruptly to the north into the Harrawa Valley in the Gadabursi country, and to the west into deep gorges which lead towards Gildessa.

- "Information on the situation of Gadabursi clan members in Gebileh in, north west of Somaliland". 1994.

the Rer Ugas, mostly in Ethiopia around Aw Bare (also called Teferi and West.

- "Theoretical and Practical Conflict Rehabilitation in the Somali Region of Ethiopia". 2018–2019. p. 8.

Jarso and Geri then sought refuge on 'neutral' adjacent Gadabursi territory in Heregel, Jarre and Lefeisa.

- "IL-DUUFKA WEYN EE LALA BEEGSADAY DAD-WEYNAHA GOBOLKA HARAWO". Harawo.org (in Somali). Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- Ali, Zeynab (2016). Cataclysm: Secrets of the Horn of Africa. ISBN 9781524564087.

- Ethnographic Survey of Africa. International African Institute. 1 January 1969. p. 26.

- "Toward a New Country in East Africa". freenation.org. Retrieved 18 August 2016.

Its nickname is Gadabursi, i.e. mountain people.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1998). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. Red Sea Press. p. 25. ISBN 9781569021057.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1998). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. Red Sea Press. ISBN 9781569021057.

At the end of the book "Tribal Distribution of Somali Afar and Saho"

- Verdier, Isabelle (31 May 1997). Ethiopia: the top 100 people. Indigo Publications. p. 13. ISBN 9782905760128.

- Hayward, R. J.; Lewis, I. M. (17 August 2005). Voice and Power. Routledge. p. 242. ISBN 9781135751753.

- The Quranyo section of the Garre claim descent from Dirr, who are born of the Irrir Samal. UNDP Paper in Kenya http://www.undp.org/content/dam/kenya/docs/Amani%20Papers/AP_Volume1_n2_May2010.pdf

- Adam, Hussein Mohamed; Ford, Richard (1 January 1997). Mending rips in the sky: options for Somali communities in the 21st century. Red Sea Press. p. 127. ISBN 9781569020739.

- Ahmed, Ali Jimale (1 January 1995). The Invention of Somalia. The Red Sea Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780932415998.

- Lewis, I. M.; Said Samatar (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Berlin-Hamburg-Münster. pp. 11–13. ISBN 3-8258-3084-5.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 9780852552803.

- Ahmed, Akbar (27 February 2013). The Thistle and the Drone: How America's War on Terror Became a Global War on Tribal Islam. Brookings Institution Press. ISBN 9780815723790.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810866041.

- Ng'ang'a, Wangũhũ (2006). Kenya's ethnic communities: foundation of the nation. Gatũndũ Publishers. ISBN 9789966975706.

- Noyoo, Ndangwa (30 January 2010). Social Policy and Human Development in Zambia. Adonis & Abbey Publishers Ltd. ISBN 9781912234936.

- Lewis, I. M.; Samatar, Said S. (1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783825830847.

- Westermann, Diedrich; Smith, Edwin William; Forde, Cyril Daryll (1 January 2007). Africa. Oxford University Press. p. 230.

- "Kinship and Contract in Somali Politics". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 77 (2): 226–249. 25 April 2007. doi:10.1353/afr.2007.0032. ISSN 1750-0184.

- Mohammad, Abdulkader Saleh (1 January 2013). The Saho of Eritrea: Ethnic Identity and National Consciousness. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643903327.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. p. 110. ISBN 9780852552803.

- Dostal, Walter (2005). Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. p. 296.

- Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

Awdal is mainly inhabited by the Gadabuursi confederation of clans.

- UN (1999) Somaliland: Update to SML26165.E of 14 February 1997 on the situation in Zeila, including who is controlling it, whether there is fighting in the area, and whether refugees are returning. "Gadabuursi clan dominates Awdal region. As a result, regional politics in Awdal is almost synonymous with Gadabuursi internal clan affairs." p. 5.

- Renders, Marleen; Terlinden, Ulf. "Chapter 9: Negotiating Statehood in a Hybrid Political Order: The Case of Somaliland". In Tobias Hagmann; Didier Péclard (eds.). Negotiating Statehood: Dynamics of Power and Domination in Africa (PDF). p. 191. Retrieved 21 January 2012.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. pp. 109. Gadabuursi in the region of Gebile/Gabilay (Woqooyi Galbeed). ISBN 9780852552803.

- Dostal, Walter; Kraus, Wolfgang (22 April 2005). Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. I.B.Tauris. p. 296. ISBN 9780857716774.

- Vries, F. W. T. Penning de (1 January 2005). Bright spots demonstrate community successes in African agriculture. IWMI. p. 67. ISBN 9789290906186.

Gadabursi, the second largest clan in Somalia, was peacefully elected as president.

- Younkins, Edward W. (15 April 2016). Ayn Rand's Atlas Shrugged: A Philosophical and Literary Companion. Routledge. ISBN 9781317176565.

- Rayne, Henry a (8 August 2015). Sun, Sand and Somals; Leaves from the Note-Book of a District Commissioner in British Somalia. BiblioLife. ISBN 9781297569760.

- Imbert-Vier, Simon (2011). Tracer des frontières à Djibouti: des territoires et des hommes aux XIXe et XXe siècles (in French). KARTHALA Editions. ISBN 9782811105068.

- "Somalia: The Myth of Clan-Based Statehood". Somalia Watch. 7 December 2002. Archived from the original on 15 June 2006. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. Walter Dostal, Wolfgang Kraus (ed.). London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". In Walter Dostal; Wolfgang Kraus (eds.). Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- Battera, Federico (2005). "Chapter 9: The Collapse of the State and the Resurgence of Customary Law in Northern Somalia". In Walter Dostal; Wolfgang Kraus (eds.). Shattering Tradition: Custom, Law and the Individual in the Muslim Mediterranean. London: I.B. Taurus. p. 296. ISBN 1-85043-634-7. Retrieved 18 March 2010.

- "IL-DUUFKA WEYN EE LALA BEEGSADAY DAD-WEYNAHA GOBOLKA HARAWO". Harawo.org (in Somali). Archived from the original on 13 March 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- "United Nations Emergencies Unit for Ethiopia, Field Trip to Jijiga (22–29 April, 1994)" (PDF). p. 2. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 December 2010. Retrieved 3 April 2011.

- http://www.fsnau.org/ipc/population-table Population census by UNFP based on Somalia.

- "Research-inspired Policy and Practice Learning in Ethiopia and the Nile region: Water and livelihoods in a highland to lowland transect in eastern Ethiopia" (PDF). 2010. p. 9.

- Burton, Richard (1856). First Footsteps in East Africa (1st ed.). Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

and thence strikes south-westwards among the Gudabirsi and Girhi Somal, who extend within sight of Harar.

- Lewis, I. M. (17 March 2003). A Modern History of the Somali: Nation and State in the Horn of Africa. ISBN 9780821445730.

- Lewis, I. M. (1998). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. p. 100. ISBN 9781569021033.

- The universal geography : earth and its inhabitants (PDF).

- Slikkerveer (28 October 2013). Plural Medical Systems in the Horn of Africa: The Legacy of Sheikh Hippocrates. Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781136143304.

- A report for the BRIDGES Project The Role of Education in Livelihoods in the Somali Region of Ethiopia Elanor Jackson. June 2011 http://fic.tufts.edu/assets/Education-Somali-Ethiopia.pdf "In the Afdem in 1989–91 there was also a clan clash between the Issa and Gedabiersay(Gadabursi)" p. 92

- An HEA Baseline Study By SC‐UK, DPPB and Partners February 2002 Sponsored by USAID/OFDA and ECHO, with additional financial support from SC‐Canada and WFP http://www.dppc.gov.et/livelihoods/somali/Downloadable/Livelihood%20Baselines/LZ%202%20Shinile%20Pastoral.pdf%5B%5D "Shinile Pastoral Livelihood Zone (Shoats, Cattle, Camel) The inhabitants of Shinile Zone are Somali peoples, most of who are from the Issa clan. Other Somali groups, Gurgura, and Gadabursi also occupy the Zone." p. 9

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1998). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press. p. 100. ISBN 9781569021033.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Central Statistical Agency Population of Ethiopia for All Regions At Wereda Level from 2014 p. 21 Somali region Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine

- H arawo State Petition, March 2011 Archived 13 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- "FindArticles.com – CBSi". Retrieved 18 January 2017 – via Find Articles.

- Mohammad, Abdulkader Saleh (1 January 2013). The Saho of Eritrea: Ethnic Identity and National Consciousness. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 162. ISBN 9783643903327.

- Mohammad, Abdulkader Saleh (1 January 2013). The Saho of Eritrea: Ethnic Identity and National Consciousness. LIT Verlag Münster. ISBN 9783643903327.

- Fage, J. D.; Oliver, Roland (1 January 1975). The Cambridge History of Africa. Cambridge University Press. p. 153. ISBN 9780521209816.

- LEWIS, I. M. (1 January 1961). "Notes on the Social Organisation of the ʿĪse Somali". Rassegna di Studi Etiopici. 17: 80. JSTOR 41299496.

- "Gadabuursi Somali subgroup, largely resident in Ethiopia (Samarron) p. 5" http://www1.uni-hamburg.de/EAE/vol2.pdf

- Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain) (1 January 1891). Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society and Monthly Record of Geography. Edward Stanford.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1961). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 207. ISBN 9783825830847.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1999). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. James Currey Publishers. pp. 211, 212. ISBN 9780852552803.

- Feyissa and Hoehne, Dereje, Markus (2007). "Resourcing State Borders and Borderlands in the Horn of Africa" (PDF). Max Planck Institute for Social Anthropology.

- Rayne, Henry a (8 August 2015). Sun, Sand and Somals; Leaves from the Note-Book of a District Commissioner in British Somaliland. BiblioLife. ISBN 9781297569760.

- Farah, Rachad (1 September 2013). Un embajador en el centro de los acontecimientos (in Spanish). Editions L'Harmattan. p. 17. ISBN 9782336321356.

- As indicated in Morin (2005:640) the name of "Cote francaise des Somalis" itself is said to have been proposed by hağği Diideh http://ediss.sub.uni-hamburg.de/volltexte/2011/5127/pdf/Yas_Diss_2010.pdf page 92

- Oberlé (Philippe), Hugot (Pierre) [1985], chapitre 4.

- Subjects of Empires, Citizens of States: Yemenis in Djibouti and Ethiopia

- Africa Analysis: The Fortnightly Bulletin on Financial and Political Trends. Africa Analysis Limited. 1987.

- Legum, Colin (2001). Africa Contemporary Record: Annual Survey and Documents. Africana Publishing Company. ISBN 9780841912212.

- Country Report: Uganda, Ethiopia, Somalia, Djibouti. The Unit. 1988.

- African Language Review, Volume 6. The University of Michigan: F. Cass. 1967. p. 5.

- Andrzejewski, B. W.; Pilaszewicz, S.; Tyloch, W. (21 November 1985). Literatures in African Languages: Theoretical Issues and Sample Surveys. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521256469.

Cabdi Deeqsi, who created a genre of love poetry called Balwo

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. p. 12. ISBN 9780810866041.

- Johnson, John William (1996). Heelloy: Modern Poetry and Songs of the Somali. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-1874209812.

- Mukhtar, Muhammad Haji (25 February 2003). Historical dictionary of Somalia. p. 12. ISBN 9780810866041.

- Mukhtar, Muhammad Haji (2000). Historical dictionary of Djibouti. p. 2. ISBN 9780810838734.

- Johnson, John William (1996). Heelloy: Modern Poetry and Songs of the Somali. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-1-874209-81-2.

- Saeed, John (15 November 1999). Somali. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-8307-8.

- Suugaan: Fasalka labaad (in Somali). Wasaaradda Waxbarashada iyo Barbaarinta. 1977.

Cali Bucul: Amaan Faras

- Suugaan: Fasalka labaad (in Somali). Wasaaradda Waxbarashada iyo Barbaarinta. 1977.

- Aspetti dell'espressione artistica in Somalia: scrittura e letteratura, strumenti musicali, ornamenti della persona, intaglio del legno (in Italian). Università di Roma La Sapienza. 1987.

- Abdullahi, Mohamed Diriye (2001). Culture and Customs of Somalia. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-31333-2.

- "Abtirsi.com: Ugasate of Gadabursi". abtirsi.com. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Nur, Sheikh Abdurahman 1993 "Ilbaxnimadii Adal Iyo Sooyaalkii Soomaaliyeed: The Renaissance of Adal Somali history". 1993.

- Sh. Nur, Sheikh Abdurahman, 2001, The Renaissance of Adal Somali history

- "Abtirsi.com : Khadija Sheikh Abba Yonis". abtirsi.com. Retrieved 30 March 2018.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1961). A Pastoral Democracy: A Study of Pastoralism and Politics Among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa. LIT Verlag Münster. p. 204. ISBN 9783825830847.

- LEWIS, I. M. (1 January 1959). "The Galla in Northern Somaliland". Rassegna di Studi Etiopici. 15: 31. JSTOR 41299539.

- Taariikhtii Ugaas Nuur

- Suugaan: Fasalka koowaad (in Somali). Wasaaradda Waxbarashada iyo Barbaarinta. 1976.

- Nur, Sheikh Abdurahman 1993 "Ilbaxnimadii Adal Iyo Sooyaalkii Soomaaliyeed: The Renaissance of Adal Somali history". 1993.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 9780810866041.

- A list of the Gadabuursi Sultans

- Iacovacci, Giuseppe; et al. (2017). "Forensic data and microvariant sequence characterization of 27 Y-STR loci analyzed in four Eastern African countries". Forensic Science International: Genetics. 27: 123–131. doi:10.1016/j.fsigen.2016.12.015. PMID 28068531. Retrieved 19 January 2018.

- http://i67.tinypic.com/357k806.jpg

- "Family Tree DNA – Somali DNA project". familytreedna.com.

- https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a7/Haplogroup_T-M184_tree.png

- "Could Thomas Jefferson's DNA Trail Reveal Middle-Eastern Origins?".

- Protonotari, Francesco (1 January 1890). Nuova antologia (in Italian). Direzione della Nuova Antologia. p. 343.

- CLANSHIP, CONFLICT AND REFUGEES: AN INTRODUCTION TO SOMALIS IN THE HORN OF AFRICA, Guido Ambroso

- Worldbank, Conflict in Somalia: Drivers and Dynamics, January 2005, Appendix 2, Lineage Charts, p. 55 Figure A-1

- Country Information and Policy Unit, Home Office, Great Britain, Somalia Assessment 2001, Annex B: Somali Clan Structure Archived 16 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine, p. 43

- Abdirahman Aw Ali (Gadabursi) selected to serve as Vice President January–May 1993. p. 9 DEVELOPMENTAL LEADERSHIP PROGRAM Policy and Practice for Developmental Leaders, Elites and Coalitions Political Settlements and State Formation: The Case of Somaliland Sarah Phillips, University of Sydney December 2013 http://publications.dlprog.org/Political%20Settlements%20and%20State%20Formation%20-%20the%20Case%20of%20Somaliland.pdf Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- Report of Ethiopia's high level delegation visit on nutrition and food security to Brazil and WFP Center of Excellence to fight Hunger (PDF). Brasilia, Brazil. p. 27. 20–28 July 2015.

- "Rise of SPDP in Addis gives green light for internal purge". Africa Intelligence. 11 November 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "PM Desalegn picks his candidate to head IGAD". Africa Intelligence. 29 July 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Nominated Ministers and Their Clans". Goobjoog. 28 January 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1958). "The Gadabuursi Somali Script". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 21 (1/3): 134–156. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00063278. JSTOR 610496.

- ʻArabfaqīh, Shihāb al-Dīn Aḥmad ibn ʻAbd al-Qādir (2003). The conquest of Abyssinia: 16th century. The Habar Makadur, underneath the page as a note [I.M. Lewis] by Richard Pankhurst. Tsehai Publishers & Distributors. p. 27. ISBN 9780972317269.

- Lewis, I.M. (1998). Peoples of the Horn of Africa: Somali, Afar and Saho. The Gadabursi. Red Sea Pr; Subsequent edition (August 1998): Red Sea Pr; Subsequent edition (August 1998). p. 25. ISBN 978-1569021040.

There are two main fractions, the Habr Afan and Habr Makadur, formerly united under a common hereditary chief (ogaz).

CS1 maint: location (link) - Farah, Rachad (1 September 2013). Un embajadoren el centro de los acontecimientos (in Spanish). Editions L'Harmattan. p. 17. ISBN 9782336321356.

- As indicated in Morin (2005:640) the name of “Cote francaise des Somalis” itself is said to have been proposed by hağği Diideh (Mahad-Ase clan of Gedebursi. He was Prosperous merchant of Zayla who built the first Mosque in Djibouti Ğami ar-Rahma in 1891) to the French administration in imitation of British Somaliland, p. 92

- "Yussur Abrar (Dir/Gadabursi), who hails from Borama in Somaliland". Africa Intelligence. 8 November 2013. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- Mukhtar, Mohamed Haji (25 February 2003). Historical Dictionary of Somalia. Scarecrow Press. p. 247. ISBN 9780810866041.

- p. 210

- geeskadmin (10 December 2014). "Kenya: Ethiopia Replaced Ambassador Shemsedin Ahmed for security reasons – Geeska Afrika Online". Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- "Somaliland's Guurti Sparks a Crisis | Crisis Group". blog.crisisgroup.org. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 5 August 2018.

- Country Information and Policy Unit, Somalia Assessment 2001, Home Office, Great Britain