Green Party (Sweden)

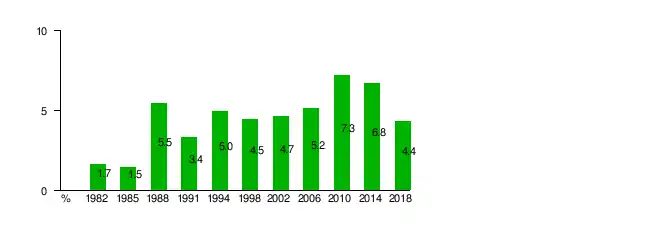

The Green Party (Swedish: Miljöpartiet de gröna, literally "Environmental Party the Greens", commonly referred to in Swedish as "Miljöpartiet" or MP) is a political party in Sweden based on green politics. The party was founded in 1981, emerging out of a sense of discontent with the existing parties' environmental policies, and sparked by the anti-nuclear power movement following the 1980 nuclear power referendum.[9] The party's breakthrough would come in the 1988 general election when they won seats in the Swedish Riksdag for the first time, capturing 5.5 percent of the vote, and becoming the first new party to enter parliament in seventy years.[10] Three years later, they dropped back below the 4 percent threshold, but returned to parliament again in 1994, and since have retained representation there. The party is represented nationally by two spokespeople, always one man and one woman. These roles are currently held by Per Bolund and Isabella Lövin.

Green Party Miljöpartiet de gröna | |

|---|---|

| Abbreviation | MP |

| Leader | Per Bolund Märta Stenevi (spokespersons) |

| Founded | 20 September 1981 |

| Headquarters | Pustegränd 1-3, Stockholm |

| Youth wing | Young Greens |

| Membership (2019) | 10,588[1] |

| Ideology | Green politics[2] |

| Political position | Centre-left[3] |

| European affiliation | European Green Party |

| International affiliation | Global Greens |

| European Parliament group | Greens–European Free Alliance |

| Nordic affiliation | Centre Group |

| Colours | Green |

| Riksdag[4] | 16 / 349 |

| European Parliament[5] | 3 / 21 |

| County councils[6] | 48 / 1,696 |

| Municipal councils[7] | 395 / 12,700 |

| Website | |

| www | |

| Part of a series on |

| Green politics |

|---|

.svg.png.webp) |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1987 | 5,500 | — |

| 1988 | 8,500 | +54.5% |

| 1989 | 8,000 | −5.9% |

| 1990 | 7,600 | −5.0% |

| 1991 | 6,900 | −9.2% |

| 1992 | 6,400 | −7.2% |

| 1993 | 5,300 | −17.2% |

| 1994 | 6,500 | +22.6% |

| 1995 | 5,600 | −13.8% |

| 1996 | 6,950 | +24.1% |

| 1997 | 7,500 | +7.9% |

| 1998 | 7,900 | +5.3% |

| 1999 | 7,285 | −7.8% |

| 2000 | 6,918 | −5.0% |

| 2001 | 6,701 | −3.1% |

| 2002 | 8,011 | +19.5% |

| 2003 | 7,483 | −6.6% |

| 2004 | 7,178 | −4.1% |

| 2005 | 7,249 | +1.0% |

| 2006 | 9,543 | +31.6% |

| 2007 | 9,045 | −5.2% |

| 2008 | 9,111 | +0.7% |

| 2009 | 10,635 | +16.7% |

| 2010 | 15,544 | +46.2% |

| 2011 | 14,648 | −5.8% |

| 2012 | 13,354 | −8.8% |

| 2013 | 13,760 | +3.0% |

| 2014 | 20,214 | +46.9% |

| 2015 | 16,735 | −17.2% |

| 2016 | 13,689 | −18.2% |

| 2017 | 10,719 | −21.7% |

| source[8] | — |

Since 3 October 2014, the Green Party is the minor partner to the Swedish Social Democratic Party in the Löfven Cabinet minority coalition government, the first time in its history that the Greens have entered government.[11]

In the 2018 general election, the Greens received 4.4% of the vote and 16 seats, making the party the smallest in the Riksdag. Despite this, the party was still able to maintain its place in government.

Ideology

Fundamental principles

In their party platform, the Greens describe their ideology as being based on "a solidarity that can be expressed in three ways: solidarity with animals, nature, and the ecological system", "solidarity with coming generations", and "solidarity with all of the world's people". A Green analysis of society is based on a holistic view – everything is connected and interdependent.

The platform then describes these solidarities being expressed in "several fundamental ideas", these being participatory democracy, ecological wisdom, social justice, children's rights, circular economy, global justice, nonviolence, equality and feminism, animal rights, self-reliance and self-administration, freedom, and long-sightedness.[12] The Swedish Green Party has its roots in the environmental, solidarity, women's rights and peace movements.

Climate change and the environment

The Green Party was the first political party in Sweden to raise the issue of climate change. Fighting climate change is a major policy issue for the party. For example, the party's main criticism of The Alliance's 2010 election manifesto was the "entirely astonishing" lack of effort in fighting climate change,[13] and in 2013, the party announced a budget proposal that was dominated by a 49 million kronor "climate package".[14] The party supports a general shift in taxation policy, towards high taxes on environmentally unfriendly or unsustainable products and activities, hoping to thus influence people's behavior towards the more sustainable.

Nuclear power

The anti-nuclear movement was a major factor in the party's creation.[9] The party's party platform reads that "we oppose the construction of new reactors in Sweden, or an increase in the output of existing reactors, and instead want to begin immediately phasing out nuclear power."[12] MP Per Bolund clarified in 2010 that the party "does not propose shutting down nuclear power reactors today, but rather phasing them out as new and renewable electricity is phased in."[15]

European integration

The party was initially opposed to membership in the European Union, and sought a new referendum on the issue. The party's EU-opposition captured them 17 percent of the votes in the 1995 European Parliament election, the first following Sweden’s EU accession.[16] The Greens included withdrawal from the EU in their party platform as recently as 2006.[17]

This policy was abolished in a September 2008 internal party referendum. [18] However, the party remains somewhat Eurosceptic. The section of the party platform on the subject opens by citing how decentralization and making decisions as locally as reasonably possible is a central part of green politics. It continues to state that the Greens "are warm adherents to international cooperation. We want to see Europe as a part of a world of democracies, where people move freely over borders, and where people and countries trade and cooperate with each other."[12]

Leadership and organisation

The Greens, like many other green parties around the world, do not have a party leader in the traditional sense. The party is represented by two spokespeople, always one male and one female. The current spokespersons are Per Bolund and Isabella Lövin.[19] The spokespeople are elected annually by the party congress, up to a maximum of nine consecutive one-year terms.[20]

The party congress, consisting of elected representatives of all of the party's local groups, is the highest decision-making organ in the Green Party. The congress, in addition to the two spokespeople, also fills many other important posts in the party, including a party board (Swedish: partistyrelse), which is the party's highest decision-making authority between party congresses, and the day-to-day operation of the party's national organisation. The congress also elects a party secretary (Swedish: partisekreterare), who is an internal, organisational leader for the party.[20] The current party secretary, initially elected by the 2019 party congress, is Märta Stenevi.

Current status

Currently, the Swedish Green Party has about 10 000 members, and is a popular party foremost among young people and women.

Organisations connected to the Swedish green party:

- The Young Greens of Sweden (Grön ungdom)

- The Green Students of Sweden (Gröna studenter)

- The Green seniors of Sweden (Gröna seniorer)

The Swedish Green party is part of the European Greens.

Criticism

Islamic extremism

The Green Party was hit by a political scandal in April 2016, as images emerged of Green Party housing minister Mehmet Kaplan attending a dinner party alongside leading members of the Turkish far-right extremist group Grey Wolves.[21][22][23][24] Following attention to comments made by Kaplan in 2009 comparing Israel to Nazi Germany, Kaplan resigned as minister, while still defended by the party leadership.[21][25] In 2014 during a seminar Kaplan equalized jihadist who travel to Syria with swedish volouteers who fought on Finland side against the Soviet Union during the Winter War 1939-1940.[26] Kaplan later defended himself as being misunderstood and said he is against "young swedes traveling to the war in Syria".[27] After his resignation, images emerged of Kaplan and other members of the Green Party displaying hand gestures associated with the Muslim Brotherhood.[21][25] Another controversy ensued as a rising Green-Party star, Yasri Khan, refused to shake hands with a female TV reporter.[23][25] Lars Nicander, director of the Centre for Asymmetric Threat Studies at the Swedish Defence University, compared the revelations with how the Soviet Union sought to infiltrate democratic Western parties during the Cold War, alleging that the Green Party similarly may have been "infiltrated by Islamists".[21][28] Yasri Khan was criticised by members within the party. He withdrew his candidacy for the Green Party executive board and also quit his seats on a regional board and city council. Spokesperson Fridolin said: men, especially those wanting to be in Swedish politics, should have no problems shaking a woman's hand. The Green Party's spokespersons also comment the debate saying there's no evidence of Islamists influencing party policies, but underlined the party needs a "reset" with greater focus on environmental issues.

In April 2016, Kamal al Raffi, a Green Party politician from the council of Burlöv Municipality as well as the chairman of the local Syrian community group invited Osama bin Laden's former advisor Salman al-Ouda to hold a lecture to be attended by his and two other community groups. This invitation was controversial in Sweden as Al-Ouda, a muslim salafist, is known for openly antisemitic views and denying the Holocaust. The Green Party politician was suspended for a time by the party leadership.[29][30] During the scandal, the party secretary promised the party will better handle crises in the future.[31]

In May 2016, Green Party co-spokesperson and Environmental Minister Åsa Romson confirmed she would resign from both positions as a result of her leadership during the party crisis, along with controversies of her own, such as referring to the September 11 attacks as the 11 September "olycka" (which can be translated as "accident", or alternatively as "misfortune" which Romson later claimed as her intention) in a television interview.[32][33][34][35]

Romson later explained her comment, and said: "Of course, the attack on New York on 11th September 2001 is one of the biggest attacks, terror-actions and assaults on the peaceful and democratic world we have seen in modern times. I have no other opinion on this matter."

Electoral politics

| Group | Votes (%) |

Avg. result +/− (pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Students | 19 | +9 |

| Members of SACO | 16 | +6 |

| Aged 18–21 | 16 | +6 |

| Aged 22–30 | 16 | +6 |

| First-time voters | 16 | +6 |

| Government employees | 12 | +2 |

| Public sector employees | 12 | +2 |

| Local government employees | 12 | +2 |

| White-collar workers | 11 | +1 |

| Employed persons | 11 | +1 |

| Members of TCO | 11 | +1 |

| Females | 11 | +1 |

| Unemployed | 10 | |

| Private sector employees | 9 | -1 |

| Males | 9 | -1 |

| Aged 31–64 | 9 | -1 |

| Blue-collar workers | 9 | -1 |

| Business owners | 8 | -2 |

| Raised outside Sweden | 7 | -3 |

| Members of LO | 7 | -3 |

| On sick leave | 7 | -3 |

| Aged 65+ | 4 | -6 |

| Farmers | 4 | -6 |

| All groups (total) | 10 | 0 |

It is often believed that the party is situated on the left on a left-right scale due to its co-operation with the Social Democratic Party. The party participated in a political and electoral coalition called the Red-Greens with the Social Democrats and Left Party from October 2008 until the 2010 general election in September 2010, and has vowed to co-operate with the Social Democrats until 2020.[37] In several municipalities, however, the Greens cooperate with liberal and conservative parties, and the party does not define itself as left, nor right. Rather, they place themselves on one end of a scale between sustainability and growth. In an article published in 2009, Maria Wetterstrand, then party co-spokesperson, defined the party as a natural home also for green-minded social liberals and libertarian socialists, by referring to its liberal policy regarding immigration and its support of personal integrity, participation and entrepreneurship, among other issues.[38]

As of 2019, the party is included in government coalition and its prioritized issues are climate change, anti-discrimination and equal rights.

Church politics

The party does not directly participate in elections to the Church of Sweden, but Greens in the Church of Sweden, an independent nominating group, participates in church elections at all levels.

Relationship with other parties

The Green Party has a good relationship with the Social Democrats, and to a lesser extent, with the Left Party. The party does not rule out participation in a government with the minor liberal and centre-right parties in Sweden. The Green Party on first entering the Riksdag, allied with the Conservative Bloc in opposition to the Social Democrats. The Green Party has made clear that its preference among cooperative arrangements with the Conservative Bloc does not include support of a government led by the liberal-conservative Moderate Party. However, historically there have been political deals concluded with the parties forming the centre-right Alliance as an example concerning education. Co-operation with the Moderate Party on the municipal level are relatively frequent.

Electoral results

General elections

| Election year |

Riksdag | County councils | Municipal councils | Ref. | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Votes | Seats won | +/– | Votes | Seats won | +/– | Votes | Seats won | +/– | ||||||||

| # | % | # | % | # | % | |||||||||||

| 1982 | 91,787 | 1.7 (#7) | 0 / 349 |

98,042 | 1.9% | 0 / 1,717 |

91,842 | 1.6% | 129 / 13,500 |

[39] | ||||||

| 1985 | 83,645 | 1.5 (#7) | 0 / 349 |

104,166 | 2.0% | 0 / 1,733 |

142,498 | 2.5% | 237 / 13,520 |

[40] | ||||||

| 1988 | 296,935 | 5.5 (#6) | 20 / 349 |

237,556 | 4,8% | 73 / 1,743 |

302,797 | 5.6% | 693 / 13,564 |

[41] | ||||||

| 1991 | 185,051 | 3.4 (#8) | 0 / 349 |

156,594 | 3.1% | 34 / 1,763 |

199,207 | 3.6% | 389 / 13,526 |

[42] | ||||||

| 1994 | 279,042 | 5.0 (#6) | 18 / 349 |

236,666 | 4.6% | 78 / 1,777 |

298,044 | 5.3% | 616 / 13,550 |

[43] | ||||||

| 1998 | 236,699 | 4.5 (#7) | 16 / 349 |

226,398 | 4.4% | 70 / 1,646 |

252,675 | 4.8% | 559 / 13,388 |

[44][45][46] | ||||||

| 2002 | 246,392 | 4.7 (#7) | 17 / 349 |

204169 | 3.9% | 55 / 1,656 |

227,189 | 4.2% | 443 / 13,274 |

[47] | ||||||

| 2006 | 291,121 | 5.2 (#7) | 19 / 349 |

[48] | ||||||||||||

| 2010 | 437,435 | 7.3 (#3) | 25 / 349 |

398,782 | 6.9% | 103 / 1,662 |

418,961 | 7.1% | 686 / 12,978 |

[49] | ||||||

| 2014 | 408,365 | 6.8 (#4) | 25 / 349 |

|||||||||||||

| 2018 | 285,899 | 4.4 (#8) | 16 / 349 |

|||||||||||||

See also

References

- "Medlemstapp i partierna - bara KD och SD ökar". Svenska Dagbladet. 15 February 2020. Retrieved 22 July 2020.

- Nordsieck, Wolfram (2018). "Sweden". Parties and Elections in Europe. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- Josep M. Colomer (25 July 2008). Political Institutions in Europe. Routledge. p. 261. ISBN 978-1-134-07354-2.

- "2018: Val till riksdagen - Valda" (in Swedish). Valmyndigheten. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Election results for the European Parliament 2019". Valmyndigheten. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "2018: Val till landstingsfullmäktige - Valda" (in Swedish). Valmyndigheten. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "2018: Val till kommunfullmäktige - Valda" (in Swedish). Valmyndigheten. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Historical Membership Numbers". Green Party of Sweden. Retrieved 11 December 2020.

- Ljunggren, Stig-Björn (2010). "Miljöpartiet De Gröna. Från miljömissnöjesparti till grön regeringspartner". Statsvetenskaplig Tidskrift. 112 (2). Retrieved 1 October 2013.

- "Allmänna valen, 1988, Del 1 Riksdagsvalet" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- Sveriges Radio. "Sweden gets a new government". Retrieved 24 February 2015.

- "Party Platform 2013" (PDF). Miljöpartiet de gröna.

- Hernadi, Alexandra (26 August 2010). "Wetterstrand: "Fullständigt häpnadsväckande"". Svenska dagbladet.

- "MP föreslår klimatpaket". Svenska dagbladet. 30 September 2013.

- "Miljöpartiet chattade om kärnkraften". Dagens Nyheter. 26 May 2010.

- Burchell, Jon (1996). "No to the European union (EU): Miljöpartiet's success in the 1995 European parliament elections in Sweden". Environmental Politics. 5 (2): 332–338. doi:10.1080/09644019608414268.

- "Miljöpartiet la fram valmanifest". Dagens Nyheter. 20 April 2006.

- "Mp skippar krav på EU-utträde". Sveriges radio (in Swedish). 6 October 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- Crofts, Maria; Nilsson, Owe (21 May 2011). "Fridolin och Romson nya språkrör". Dagens Nyheter (in Swedish). Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- "Stadgar" [Constitution] (in Swedish). Miljöpartiet de gröna. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Sweden's Green Party hit by religious row". Al Jazeera. 27 April 2016.

- "Housing minister, Turkish extremists dined together". Radio Sweden. 14 April 2016.

- "Swedish cabinet member compared Israel with Nazi-Germany". Svenska Dagbladet. 17 April 2016.

- "Sweden's housing minister Mehmet Kaplan quits after his Nazi comparison to Israel". International Business Times. 18 April 2016.

- "Green Party leaders: We have no plans to resign". The Local. 25 April 2016.

- "Mehmet Kaplan avgår efter kritiken". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- Kaplan, Mehmet (3 October 2014). "Angående Mehmet Kaplans uttalande om svenskar som stred i Finland". Miljöpartiet. Retrieved 13 January 2021.

- "'Green Party may have been infiltrated by Islamists'". The Local. 23 April 2016.

- "Tre olika Malmöföreningar ville lyssna på bin Ladins förra mentor". Sydsvenskan. 28 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- "Efter skandalinbjudan – Miljöpartisten tar time-out". Sveriges Television www.svt.se. 27 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- "MP: Inget tyder på att islamistisk infiltration är reell" (in Swedish). Svenska Dagbladet. 24 April 2016.

- "Swedish deputy premier resigns amid Green Party crisis". Yahoo News/AP. 9 May 2016.

- "Green leader steps down as government minister". The Local. 9 May 2016.

- "Lövin recommended to replace Romson". Radio Sweden. 9 May 2016.

- "Swedish Greens vote in their new co-leaders". The Local. 13 May 2016.

- Holmberg, Sören; Näsman, Per; Wänström, Kent (2010). Riksdagsvalet 2010 Valu (PDF) (Report). Sveriges Television. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 June 2011. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- "Partiledarna litar inte på Lars Ohly". Aftonbladet (in Swedish). 3 October 2008. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- Wetterstrand, Maria (17 November 2009). "Wetterstrand: De gröna ett naturligt hem för socialliberaler". Newsmill (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 21 May 2011.

- "Allmänna valen 1982" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- "Allmänna valen 1985" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- "Allmänna val 1988" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- "Allmänna val 1991" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- "Allmänna val 1994, del 2" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- "Allmänna valen 1998, del 3 Kommunfullmäktige" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- "Allmänna valen, Del 2 Landstingsfullmuaktige" (PDF). Statistics Sweden.

- "Procent- och mandatfördelning riksdagsvalet 1998". Valmyndigheten (Swedish Election Authority). Archived from the original on 18 September 2010. Retrieved 30 September 2013.

- "Val 2002: Slutresultat". Valmyndigheten.

- "Val 2006, Slutresultat". Statistics Sweden.

- "Val 2010, Slutresultat". Statistics Sweden.