Havasu Creek

Havasu Creek is a stream in the U.S. state of Arizona associated with the Havasupai people. It is a tributary to the Colorado River, which it enters in the Grand Canyon.

| Havasu Creek | |

|---|---|

Travertine formations | |

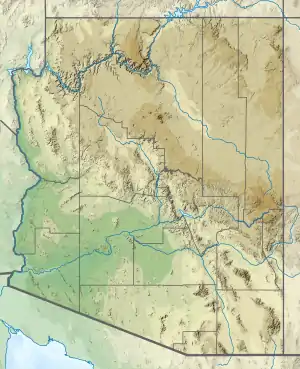

Location of the mouth of Havasu Creek in Arizona | |

| Etymology | ha "water" + vasu "blue-green"[1] |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Arizona |

| County | Coconino |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Havasupai Indian Reservation |

| • location | Havasu Springs |

| • coordinates | 36°13′00″N 112°41′13″W[2] |

| • elevation | 3,260 ft (990 m)[3] |

| Mouth | Colorado River |

• location | Havasu Rapids, Grand Canyon |

• coordinates | 36°18′28″N 112°45′43″W[2] |

• elevation | 2,093 ft (638 m)[2] |

| Discharge | |

| • minimum | 1 cu ft/s (0.028 m3/s) |

Stream course and features

Havasu Creek is the second largest tributary of the Colorado River in Grand Canyon National Park.[4] The drainage basin for Havasu Creek is about 3,000 square miles (7,800 km2). It includes the town of Williams, Arizona, and Grand Canyon Village.[5]

Havasu Creek starts out above the canyon wall as a small trickle of snow run-off and rain water. This water meanders on the plains above the canyon for about 50 miles (80 km) until it enters Cataract Canyon (also known as Havasu Canyon). It then reaches Havasu Springs, where an underground source feeds the creek. This spring can be accessed by heading upstream when the creek is first encountered. Water temperature varies from the low seventies during the warmer half of the year, to the mid-fifties in winter.[6][7] The creek is well known for its blue-green color and distinctive travertine formations. This is due to large amounts of calcium carbonate in the water that formed the limestone that lines the creek and reflects its color so strongly. This also gives the creek an interesting feature, as it is ever-changing. This occurs because any items that fall into the stream mineralize very quickly, causing new formations and changing the flow of the water. This causes the creek to never look the same from one year to another. The creek runs through the village of Supai, and it ultimately flows into the Colorado River.

Navajo Falls

Until the August 2008 flooding, Navajo Falls was the first prominent waterfall in the canyon. They were named after an old Supai chief. It was located 1.25 miles (2 km) from Supai and is accessed from a trail located on the left side (right side when heading upstream) of the main trail. This side trail leads down to the creek, where there is a crude bridge that crosses over the creek. The trail then leads back into the trees, where the main pool and falls were located. The pool was popular for its seclusion and its ease to swimmers. The falls were approximately 70 feet (21 m) tall and consisted of separate sets of water chutes, the main one located on the right side where the water cascaded down the canyon hill. To the left of the main chute there were other smaller ones that were steeper and more vertical. There were a few places that are viable for cliff jumping, although caution was necessary.

In August 2008, Navajo Falls was completely bypassed by a flood. According to The New York Times:

Within 12 hours, several surges of high water roared down the creek, destroying the campground, stranding a Boy Scout troop from New Jersey and setting off a massive mudslide that obliterated Navajo Falls, one of four spectacular canyon waterfalls that attract tourists from around the world.

Despite this early report, the site of the falls still exists; the mudslide simply rerouted Havasu Creek.[9]

Fiftyfoot Falls

This waterfall, also called Upper Navajo Falls, became more prominent in the 2008 flood that bypassed Navajo Falls, and is now the first waterfall in the canyon. The falls are about 50 feet (15 m) tall and fall into a rocky pool.[10][11]

Originally known as Supai Falls, this waterfall has been the most unstable waterfall in Havasu Canyon since 1885, disappearing and reappearing several times. The most recent reappearance was in 1970.[12]

Lower Navajo Falls

This waterfall, also called Rock Falls, was created by the 2008 flood, about .15 miles (0.24 km) below Fiftyfoot Falls. The creek falls about 30 feet (9.1 m) into a swimming hole.[13]

Havasu Falls

Havasu Falls (Havasupai: Havasuw Hagjahgeevma[14]) is the third waterfall in the canyon. It is located at 36°15′18″N 112°41′52″W (1 ½ miles from Supai) and is accessed from a trail on the right side (left side when heading upstream) of the main trail. The side trail leads across a small plateau and drops into the main pool. Havasu is arguably the most famous and most visited of all the falls. The falls consist of one main chute that drops over a 100-foot (30 m) vertical cliff[15] (due to the high mineral content of the water, the falls are ever-changing and sometimes break into two separate chutes of water) into a large pool.

The falls are known for their natural pools, created by mineralization, although most of these pools were damaged and/or destroyed in the early 1990s by large floods that washed through the area. A small man-made dam was constructed to help restore the pools and to preserve what is left. There are many picnic tables on the opposite side of the creek and it is very easy to cross over by following the edges of the pools. It is possible to swim behind the falls and enter a small rock shelter behind it.

Before the flood of 1910, the falls were called "Bridal Veil Falls" because they fell from the entire width of the now-dry travertine cliffs north and south of the present falls.

Mooney Falls

Mooney Falls is the fourth main waterfall in the canyon. It is named after D. W. "James" Mooney, a miner, who in 1882 – according to his companions – decided to mine the area near Havasu Falls for minerals. The group then decided to try Mooney Falls. One of his companions was injured, so James Mooney decided to try to climb up the falls with his companion tied to his back, and subsequently fell to his death. The Falls are located 2.25 miles (3.6 km) from Supai, just past the campgrounds. The trail leads to the top of the falls, where there is a lookout/photograph area that overlooks the 210-foot (64 m) canyon wall that the waterfall cascades over. In order to gain access to the bottom of the falls and its pool, a very rugged and dangerous descent is required. Extreme care and discretion for the following portion is required; it is highly exposed and should not be attempted when the weather and/or conditions are not suitable.

The trail down is located on the left side (looking downstream), up against the canyon wall. The first half of the trail is only moderately difficult until the entrance of a small passageway/cave is reached. At this point the trail becomes very difficult and very precarious. The small passageway is large enough for the average human, and leads to a small opening in which another passageway is entered. At the end of the second passageway the trail becomes a semi-vertical rock climb that is similar to descending a ladder. Strategically placed chains, handholds, and ladders aid in the climb.

Mist from the falls often makes the rock slippery, and the climb is also difficult because of having to pass people going in the opposite direction. The pool is the largest of the three, and some people jump from low cliff ledges into the pool. It is possible for strong swimmers to swim to the left of the falls to the rock wall and then to a small cave that is located just above the water line, approximately 15–20 feet (5 to 6 meters) away from the falls. An island breaks the pool into two streams.

Beaver Falls

Beaver Falls is arguably the fifth set of falls, although many claim that it is not a waterfall, but merely a set of small falls that are located close to each other. The falls are located approximately 6 miles (9.7 km) downstream of Supai, and are the most difficult to access. After the descent to Mooney Falls, a visible trail leads downstream.

About .25 miles (0.40 km) down, a small stream feeds into the creek, over the side of the cliff, effectively creating a place to shower. The trail leads to the right towards the creek, then back towards Mooney Falls to get to this mini-waterfall.

The next 3–4 miles are remote and rugged. The trail is not always easy to follow and requires multiple crossings of the creek. At one point, after a large, oddly out of place palm tree, a rope had been placed for climbing a rock wall in order to further traverse the trail down the canyon. This has now been replaced with a much more navigable ladder.

Farther downstream, a rock chute/slide provides one access to Beaver Falls. Easier access is further along, just before the trail turns north to continue down the canyon. River rafters have beaten a path to the ledges where they jump. Turning upstream from here, it is possible to gradually get to the creek bed and follow it further upstream to the falls. The pools here are small, but still offer good swimming.

Beaver Falls was once much more impressive. It had a height of about fifty feet in one fall, at the junction of Beaver Canyon and Havasu Canyon. The great flood of January 1910 destroyed it, leaving the falls over the limestone ledges as they are today. Rotted cottonwood logs near the aforementioned junction show how high the water rose during that flood.

Other waterfalls

Frequent flooding changes the appearance of some waterfalls and causes others to appear and disappear. Navajo Falls (above) is one such example.

Confluence

The creek flows to the Colorado River from Beaver Falls. There are multiple ways to reach the river, including going back up the chute to the trail and continuing downstream. The 3 miles (4.8 km) hike is long, difficult, and rugged, and it is advisable only for experienced hikers. The creek ends at the confluence, where there are some camping areas. This spot is also popular for river rafters to stop and to head up the canyon.

Flooding

Flooding is common along Havasu Creek. A government report lists 14 "historic floods" from 1899 to 1993.[16] One such flood occurred on August 17, 2008, when the Redlands Dam on Havasu Creek burst after days of heavy rain. The floodwaters' threat to human life led local authorities to evacuate the village. Rescue crews airlifted about 400 people to safety.[17] Navajo Falls was bypassed in the flooding, Fiftyfoot Falls became more prominent, and Lower Navajo Falls was formed.[10][18]

Gallery

Mooney Falls in the morning

Mooney Falls in the morning Navajo Falls before the flood

Navajo Falls before the flood Havasu Falls at night, before 2008 flash flood

Havasu Falls at night, before 2008 flash flood Mooney Falls

Mooney Falls Beaver Falls

Beaver Falls Havasu Falls prior to 2008 flash flood

Havasu Falls prior to 2008 flash flood Oblique air photo of the canyon of Havasu Creek flowing into the Colorado River in the foreground

Oblique air photo of the canyon of Havasu Creek flowing into the Colorado River in the foreground

References

- Griffin-Pierce, Trudy (2013). The Columbia Guide to American Indians of the Southwest. Columbia University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-231-52010-2.

- "Havasu Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. February 8, 1980. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- Source elevation derived from Google Earth search using GNIS source coordinates.

- West; Mead; English; Stuckey (2009-09-01). "Havasu Creek Watershed Scoping Project Final Report": 4. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Havasu Canyon Watershed Rapid Watershed Assessment Report" (PDF). USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service and University of Arizona, Water Resources Research Center. 2010-06-01: S1P2, S2P1. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Trammell, Melissa; Healy, Brian; Smith, Emily Omana; Sponholtz, Pamela (2012). Humpback Chub Translocation to Havasu Creek, Grand Canyon National Park. U.S. National Park Service. p. 19.

- "USGS Current Conditions for USGS 09404115 HAVASU CREEK ABOVE THE MOUTH, NEAR SUPAI, AZ". U.S. Geological Survey. 2019-09-22.

- Havasupai Falls net: Navajo Falls

- "World Waterfall Database - Fiftyfoot Falls". Retrieved 16 September 2019.

- "GNIS Detail - Fiftyfoot Falls". USGS. 2019-09-16.

- Melis, Phillips, Webb and Bills (1996). "When the Blue-Green Waters Turn Red: Historical Flooding in Havasu Creek, Arizona" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. p. 37. Retrieved 24 September 2014.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Havasupai Falls net: Lower Navajo Falls

- Hinton, Leanne (1984). A dictionary of the Havasupai language.

- "Waterfalls of Havasu Canyon". Retrieved 2013-06-12.

- Melis, Phillips, Webb and Bills (1996). "When the Blue-Green Waters Turn Red: Historical Flooding in Havasu Creek, Arizona" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey. pp. 36 (Table 3). Retrieved 24 September 2014.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Reid, Betty; Boehnke, Megan; Leung, Lily (August 17, 2008). "Hundreds Evacuated Near Grand Canyon After Flooding". The Arizona Republic. Retrieved November 29, 2012.

- Fonseca, Felicia; Associated Press (June 2009). "Havasupai Reopen Flooded Site to Visitors". News from Indian Country. Retrieved January 26, 2012.