History of Malawi

The History of Malawi covers the area of present-day Malawi. The region was once part of the Maravi Empire. In colonial times, the territory was ruled by the British, under whose control it was known first as British Central Africa and later Nyasaland.[1] It became part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The country achieved full independence, as Malawi, in 1964. After independence, Malawi was ruled as a one-party state under Hastings Banda until 1994.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Malawi |

|

|

|

Prehistory

In 1991 a hominid jawbone was discovered near Uraha village that was between 2.3 and 2.5 million years old.[2] Early humans inhabited the vicinity of Lake Malawi 50,000 to 60,000 years ago. Human remains at a site dated about 8000 BCE showed physical characteristics similar to peoples living today in the Horn of Africa. At another site, dated 1500 BCE, the remains possess features resembling San people. They might be responsible for the rock paintings found south of Lilongwe in Chencherere and Mphunzi. According to Chewa myth, the first people in the area were a race of dwarf archers which they called Akafula or Akaombwe.[3] Bantu-speaking people entered the region during the four first centuries of the "Common Era", bringing use of iron and slash-and-burn agriculture. Later waves of Bantu settlement, between the 13th and 15th centuries, displaced or assimilated the earlier Bantu and pre-Bantu populations.[4]

Maravi Empire

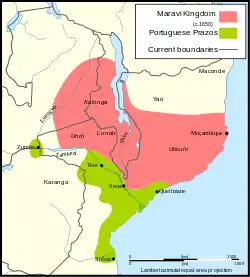

The name Malawi is thought to derive from the word Maravi. The people of the Maravi Empire were iron workers. Maravi is thought to mean "Flames" and may have come from the sight of many kilns lighting up the night sky. A dynasty known as the Maravi Empire was founded by the Amaravi people in the late 15th century. The Amaravi, who eventually became known as the Chewa (a word possibly derived from a term meaning "foreigner"), migrated to Malawi from the region of the modern-day Republic of Congo to escape unrest and disease. The Chewa attacked the Akafula, whom no longer exist.

Eventually encompassing most of modern Malawi, as well as parts of modern-day Mozambique and Zambia, the Maravi Empire began on the southwestern shores of Lake Malawi. The head of the empire during its expansion was the Kalonga (also spelt Karonga). The Kalonga ruled from his headquarters in Mankhamba. Under the leadership of the Kalonga, sub-chiefs were appointed to occupy and subdue new areas. The empire began to decline during the early 18th century when fighting among the sub-chiefs and the burgeoning slave trade weakened the authority of the Maravi Empire.

Trade and invasions

_(14780571234)%252C_white_background.jpg.webp)

Portuguese influence

Initially, the Maravi Empire's economy was largely dependent on agriculture, especially the production of millet and sorghum. It was during the Maravi Empire, sometime during the 16th century, that Europeans first came into contact with the people of Malawi. Under the Maravi Empire, the Chewa had access to the coast of modern-day Mozambique. Through this coastal area, the Chewa traded ivory, iron, and slaves with the Portuguese and Arabs. Trade was enhanced by the common language of Chewa (Nyanja) which was spoken throughout the Maravi Empire.

In 1616 the Portuguese trader Gaspar Bocarro journeyed through what is now Malawi, producing the first European account of the country and its people.[5][6] The Portuguese were also responsible for the introduction of maize to the region. Maize would eventually replace sorghum as the staple of the Malawian diet. Malawian tribes traded slaves with the Portuguese. These slaves were sent mainly to work on Portuguese plantations in Mozambique or to Brazil.

Angoni

The decline of the Maravi Empire resulted from the entrance of two powerful groups into the region of Malawi. In the 19th century, the Angoni or Ngoni people and their chief Zwangendaba arrived from the Natal region of modern-day South Africa. The Angoni were part of a great migration, known as the mfecane, of people fleeing from the head of the Zulu Empire, Shaka Zulu. The Ngoni people settled mostly in what is modern-day central Malawi; particularly Ntcheu and parts of Dedza district. However, some groups proceeded north; entering Tanzania and settling around Lake Victoria. But splinter groups broke off and headed back south; settling in modern-day northern Malawi, particularly Mzimba district, where they mixed with another migrant group coming from across Lake Malawi called the Bawoloka. Clearly, the mfecane had a significant impact on Southern Africa. The Angoni adopted Shaka's military tactics to subdue the lesser tribes, including the Maravi, they found along their way. Staging from rocky areas, the Ngoni impis would raid the Chewa (also called Achewa) and plunder food, oxen and women. Young men were drawn in as new fighting forces while older men were reduced to domestic slaves and/or sold off to Arab slave traders operating from the Lake Malawi region.

Yao

The second group to take power around this time was the Yao. The Yao were also known by a derogatory term Achawa or Machawa, which is a word used by many people in southern Africa. The author of the History of the Yao (Chiikala ChaWayao), Yohanna Abdallah argued that it was the Mang'anja who coined the term Achawa in reference to the Yao because the Mang'anja and later on the Makuwa-Lomwe failed to pronounce the proper name of Yao; Edward Alpers states that the term Achawa might have originated from the Lomwe who knew the Yao as a people who ate their own food (anolya achawa). The Yao were richer and more independent than the Makuwa. They came to Malawi from northern Mozambique to escape either from famine or conflict with the Makuwa people who were jealous of the Yao. The factors which caused the Yao to migrate from Yaoland are complicated and need extensive research. One factor is that the Makuwa attacked the Yao due to jealousy. The Makuwa tribe had become enemies of the Yao because of the wealth the Yao were amassing through trading ivory and later on slaves to Arabs from Zanzibar and the Portuguese after the French had introduced sugar plantations on Réunion Island and Mauritius. It was the French who influenced the Sultan of Zanzibar to procure slaves from the hinterland. In due course the Arabs, who had known the Yao before the Portuguese, asked the Yao to go to the interior and bring slaves rather than bringing ivory. The Yao, upon migrating to Malawi in the 1800s, soon began buying slaves from the Chewa and Ngoni. The Yao are recorded to have also attacked them in order to capture prisoners whom they later sold as slaves. It was through David Livingstone the world learnt that the Yao were great slavers who were capturing the Mang'anja. However, Livingstone saw for the first time the Portuguese from Angola capturing slaves in Botswana in 1852. The people of chief Sebetwane in Botswana were being raided by the Portuguese slavers. This was the period before Livingstone came to Malawi in 1859.

In 1859 Livingstone recorded that he had discovered Lake Malawi. The Yao who were already settled by the lake told him that the mass of water he saw was called Nyasa. Livingstone, who did not know Chiyao, possibly thought that Nyasa was the proper name of the lake. However, the term Nyasa in Chiyao meant the lake in English.

Within two years of the discovery of the Lake Nyasa, Livingstone had to review his plans for colonising Malawi. He used the church to start the process of colonising the land. He brought the Universities Mission to Central Africa (U.M.C.A) under Bishop Frederick Mackenzie in 1861 to Magomero. The Yao had already settled in Magomero before 1860 and the Christian missionaries encountered resistance from them. The Yao of Magomero had embraced Islam before the 1860s. Bishop Mackenzie and Livingstone took sides with the Mang'anja who were non-Muslims. Wars erupted between the Yao and Bishop Mackenzie. Livingstone and Bishop Mackenzie shot the Yao, burnt their houses and fields (see Magomero: The Portrait of an African village). The wars between the Yao and Livingstone at Magomero in 1861 do not appear clearly in the history textbooks of Malawi.

Work at the University of Malawi (UNIMA) for long time has been studies on how to demolish the Yao history (see The Creation of Tribalism in Southern Africa (ed.) Leroy Vail). The Magomero wars in 1861 were the first wars encountered in Malawi between Christian missionaries and Yao Muslims. Livingstone and the U.M.C.A were criticized for attacking the Yao. Instead of preaching the gospel the missionaries engaged in politics at Magomero by siding with the Mang'anja. The Yao were regarded as intruders, invaders, and foreigners by the missionaries. The point is that by the 1860s, a number of Yao people had already embraced Islam and it was difficult for the missionaries to convert them. They had already heard the stories of Jesus through the Quranic interpretations during Siyala preachings and they felt insulted to be regarded as uncivilized. Christian missionaries had a tendency to call Africans infidels if they did not convert to Christianity. In the minds of Christian missionaries, all Africans were uncivilized. They came to Africa to civilize the infidels. The missionaries are said to have brought the three Cs to Malawi i.e. Civilisation, Commerce and Christianity. It was the Mang'anja who had not yet embraced Islam before the arrival of the Christian missionaries. However, Islam appeared among the Mang'anja of the Shire valley in the 1500s when the Arabs were trading with the Phiri. Some Africans had already embraced Islam at that period. However, the presence of Arabs along the Zambezi-Shire dwindled after the Portuguese killed and enslaved a number of Muslims. Muslim slaves were taken to Brazil. This was the end of Islamic influence in the Zambezi-Shire valley. The Portuguese had to follow the Muslims from Tete up to Zimbabwe where they uprooted their presence (see Nyasaland Handbook by S.S. Murray, 1932).

When David Livingstone and Bishop Mackenzie came to Magomero in 1861 they found the Yao and the Mang'anja living side by side. The Yao were already civilised at that period. They were dressed in long robes and kofias (skull caps), and were trading with the Rwozi kingdom in Zimbabwe, with Bisa in the Luangwa valley, with the Lunda of Mwata Kazembe of Zambia, and even going to Congo and the east coast. Kilwa and Unguja (Zanzibar) were the Yao lodestars. The Yao travelled extensively in this part of Africa. The long trade expeditions needed people who knew some geography and arithmetic (masoma ga yisabu) in order to do their business transactions. The Yao had already acquired some skills in reading and writing using the Arabic alphabet, building dhows (yombo) along the lake shore, irrigation (matimbe), growing rice, and founding madrassahs and boarding schools (chiwuwo). The Yao were the first, and for a long while, the only group to use firearms, which they bought from Europeans and Arabs, in conflicts with other tribes. With the use of firearms the Yao in southern Malawi helped to defend the Mang'anja, who were being attacked by the Kololo. The Kololo were a people who came to Malawi from chief Sebetwane of Botswana. They were porters of Livingstone. David Livingstone left them in the Shire valley armed with guns which they used to terrorise and kill the Mang'anja in order to usurp the Mang'anja chieftainships of Chibisa and Tengani. Thanks to the Yao, the Mang'anja were not wiped out from the map of Malawi. The Yao even supplied guns to chief Mwase Kasungu of Kasungu district who was being terrorised by the Ngoni followers of chief M'mbelwa of Mzimba. Mwase's guns helped to defend the Chewa from the Ngoni and from wild animals.

In the course of history the Yao were later on depicted as a people who were enslaving the original inhabitants. In fact the Yao were resisting colonisation of Malawi in the name of spreading Christianity, Civilisation and Commerce. After failing to convert the Yao in Magomero in 1861, the Scottish decided to send another group of missionaries. The Free church of Scotland arrived in Mangochi in 1875. The Scots also sent another group of missionaries to convert the Yao Muslims in Kapeni-Blantyre in 1876. Chief Kapeni gave land to the Established Church of Scotland in Blantyre where they built what is known as H.H.I.

In 1875, Chief Mponda, a Yao Muslim, welcomed the Christians to open a mission in Cape Maclear. For six years the missionaries who settled among the Yao in Mangochi, i.e. the Free Church of Scotland, failed to convert Muslims to Christianity. Bishop Robert Laws decided to leave Mangochi and go further north to Tonga and Tumbuka territories. The Tumbuka and the Tonga were being terrorised by the Ngoni impis of chief M'mbelwa of Mzimba (a Zulu word for the body). A good number of the Tumbuka were the slaves of the Ngoni, whom they called Zowa. The Ngoni had already killed one of the Chikulamayembes (Mkwayira the chief of the Tumbuka) and Mjuma along the Runyina river. With this background, the Free Church of Scotland found fertile ground for the gospel. The Tumbuka and the Tonga were living in fear of the Ngoni. By 1881 the missionaries opened a station at Bandawe which was a center of writing and reading in Nkhata Bay. A school was a church and the church was a school. It was a buffer zone between the Ngoni and the Tonga. It acted as a center of protection from the marauding Ngoni impis. The Tongas for the first time embraced western civilization and they became the first people to be literate through English. Some of the teachers of the Tonga were the Nyanja who had embraced Christianity at Cape Maclear in Mangochi. Later on the missionaries went to the Tumbuka, who were also being enslaved by the powerful Ngonis. Robert Laws opened a mission station in Livingstonia near Rumphi in 1894. The Tumbuka sought refuge among the missionaries and embraced Christianity. They became the second tribe to be the most educated in Malawi. It can be observed that by that period the Yao had completely distanced themselves from Christian education. They were still stuck with eastern influence. They were writing and reading in Arabic. It was a blow to the Yao as Arabic education was not recognized in Malawi from 1860s up to modern times. An educated person from the 1870s up to the 1940s was the one who had an encyclopedic knowledge of the Bible, some arithmetic and English. It was from the 1940s when the government took steps to change the image of education in Malawi. Before 1940, education in Malawi was controlled by the Church.

While the Free Church of Scotland in 1875 went to the Yao Muslims of chief Mponda, the Established Church of Scotland in 1876 also went to the Yao Muslim chief Kapeni of Blantyre. Meanwhile, the White Fathers of the Catholic Church in 1889 sought permission to open a mission station in the territory of Chief Mponda of Mangochi. The Yao had built big towns in Mangochi, and the Mpondas and Makanjila had plenty of food which attracted foreigners. The missionaries aimed to convert the Muslims of Kapeni in Blantyre, and the Mpondas and Makanjila in Mangochi. The Yaos were one of the strongest tribes in Malawi. The second were the Ngoni who used the tactics of Shaka Zulu in their fighting.

The failure to convert the Yao Muslims to Christianity contributed to the appearing of the negative history of the Yao people. The Yao socio-economic contribution to Malawi was not recognised, rather history judged them as great slave traders. H. H. Johnson before he came to Malawi had already planned to uproot the influence of 17 Yao chiefs and 2 Ngoni chiefs. On the list were chiefs such as Jalasi, Mponda, Makanjila, Chikumbu, Mtilamanja, Matipwili of the Yao and Gomani of the Ngoni. Powerful chiefs in southern Africa were to be targeted in order to create the British empire from the Cape to Cairo. This was the dream of Cecil Rhodes. It started in South Africa where Cecil Rhodes's influence through the British crushed the Zulu kingdom, the Pedi, Ndebele of Zimbabwe and the Lozi of Zambia. With funding from Cecil Rhodes, from 1891 Johnson fought with the Yao for five years before they were subdued. Makanjila, Mponda Jalasi were the strongest Yao chiefs who fought the British under H.H. Johnson's command.

The history of the Yao conversion to Islam can be traced through their long expeditions to the east coast especially to Kilwa and Zanzibar. The Yao had begun to be attracted and converted to Islam before the 1840s. Salim bin Abdallah, who is better known as the Jumbe of Nkhotakota, followed in the Yao footsteps in 1840. It was from the Yao and the Nyamwezi he got accurate information about the geography of Malawi. In Nkhotakota Jumbe employed a number of Yao and Bisa. The Bisa had known the Yao through the ivory trade which they had both practised along the Luangwa valley where elephants were abundant. It must be understood that Islam in Malawi can be divided into phases [see the History of Islam in Malawi Before and after Christianity by Valiant Mussa, Blantyre: Fattan, 2005]. The Yao ruling class, particularly chief Makanjila, officially is said to have recommended Islam in 1870 like their Arab trading partners rather than the traditional belief in Mnungu. The Yao were not animist before Islam. They knew that there is one God known as Amanani, Achipinga, or Wakalakatele. They did not worship idols; rather their spiritual place was under an Msolo tree where they asked the assistance of God through amasoka (ancestral spirits). They believed that it was impossible to approach God directly but through Amasoka. As a benefit of their conversion, the Yao employed Swahili and Arab sheikhs from the coast who promoted literacy and founded mosques. Chief Mponda in Mangochi had almost twelve madrassas before the Christian missionaries arrived in 1875. At those madrassas Yao children were taught how to read and write before the Christian missionaries arrived in 1875. The Yao were the first people in Malawi to be literate. They learnt how to read and write through the Arabic alphabet. Their writings were in the Kiswahili language, which became a lingua franca of Malawi from 1870 to the 1960s. In contemporary history the Yao are known as illiterate people because they did not embrace western education which had a condition of one converting to Christianity before going to school. The school was the church and church was a school. In this way the Yao distanced themselves from the school. The most educated people in Malawi were found in Nkhata Bay and Rumphi. These were the two places where the Tonga in 1881 and the Tumbuka in 1894 embraced Christianity out of fear of the powerful Ngoni impis who were terrorizing them (see The Creation of Tribalism in southern Africa (ed.) Leroy Vail). The first people to attend school were the Tumbuka slave children. The Ngoni with their children were suspicious of the penetration of the missionaries in their domain. Today we find few Yaos in government departments, which has forced a large number of them to migrate to South Africa as a source of labour. In Malawi the Yao are farmers, tailors, hawkers, guards, fishermen and working in unskilled manual jobs. From the 1980s the Yao have been sending their children to foreign universities because it has been difficult for them to study at the University of Malawi since 1965. At the present time government departments have employed graduates from University of Zanzibar, the Islamic university of Uganda and International University of Sudan. The Yao believe that they have been deliberately marginalized by the authorities because of their faith. A number of Yao Muslims at one time concealed their Yao or Islamic names in order to pass to secondary school. Mariam was known as Mary; Yusufu was called Joseph; Che Sigele became Jeanet.

Arabs and their Swahili allies

Using their strong partnership with the Yao, the Arab traders set up several trading posts along the shore of Lake Malawi. The Yao expeditions to the east attracted the attention of the Swahili-Arabs. It was from the Yao, the Swahili and Arabs knew the existence and the geography of Lake Malawi. Jumbe (Salim Abdallah) followed the Yao trade route from the eastern side of Lake Malawi up to Nkhotakota. When Jumbe arrived in Nkhotakota in 1840 he found a number of Yao and Bisa well established. Some of those Yao he found in Nkhotakota were already Islamised and he opted to employ them rather than employing non-Muslim Chewa. During the height of his power, Jumbe transported between 5,000 and 20,000 slaves through Nkhotakota annually. From Nkhotakota, the slaves were transported in caravans of no less than 500 slaves to the small island of Kilwa Kisiwani off the coast of modern-day Tanzania. The founding of these various posts effectively shifted the slave trade in Malawi from the Portuguese in Mozambique to the Arabs of Zanzibar.

Although the Yao and the Angoni continually clashed with each other, neither was able to win a decisive victory. However, the Ngoni of Dedza opted to work to work the Yao of Mpondas. The remaining members of the Maravi Empire, however, were nearly wiped out in attacks from both sides. Some Achewa chiefs saved themselves by creating alliances with the Swahili people who were allied with the Arab slave traders.

Lomwe of Malawi

The Lomwe of Malawi are a recent introduction having arrived as late as the 1890s. The Lomwe came from a hill in Mozambique called uLomwe, north of the Zambezi River and south east of Lake Chilwa in Malawi. Theirs was also a story of hunger largely instigated by the Portuguese settlers moving into the neighbourhoods of uLomwe.[7] To escape from ill-treatment, the Lomwe headed north and entered Nyasaland by way of the southern tip of lake Chilwa, settling in the Phalombe and Mulanje areas.

In Mulanje they found the Yao and Mang'anja already settled. The Yao chiefs such as Chikumbu, Mtilamanja, Matipwili, Juma, Chiuta welcomed the Lomwe as their cousins from Mozambique. A large number of Lomwe were given land by the Yao and Mang'anja. Later on the Lomwe got employment on tea estates that various British companies were establishing on the foothills of Mount Mulanje. They gradually spread into Thyolo and Chiradzulu. The Lomwe readily mixed with the local Mang'anja tribes, and there are no reported cases of tribal conflict.

Early European contact

The location of Malawi was known to the Arabs and Swahili of the east coast through the Yao.[8] Later on it was the Portuguese who learnt of the existence of Lake Malawi. After the Portuguese arrival in the area in the 16th century, the next significant Western contact was the arrival of David Livingstone along the shore of Lake Malawi in 1859. Livingstone is said to have heard about the existence of Lake Malawi from a Portuguese in Tete. In 1859 it is recorded that he discovered the mass of water which was called by Yao people as Nyasa in Chiyao. Livingstone was surprised seeing the presence of Islam among the Yao of chief Mponda who had more than twelve madrassas running Islamic lessons, writing and reading Arabic. With this background, Livingstone painted a gloomy picture of the Mang'anja being captured, killed and enslaved by the marauding Yao from Mozambique. In 1861 under Bishop Charles Mackenzie missionaries of the Universities' Mission to Central Africa (U.M.C.A) were sent to open a mission in Magomero where the Yao were already Muslims. The bishop and Livingstone took the side of the Mang'anja in the politics of that area. Wars between the Yao and Bishop Mackenzie were fought. Crops and villages of the Yao were burnt by Livingstone and Bishop Mackenzie. (See Magomero A portrait of an Africa village by Landeg White). The mission was abandoned after the death of Bishop Mackenzie. The U.M.C.A shifted its sphere to Morumbala in Mozambique.

After the failure of the U.M.C.A in Magomero, Scottish Presbyterian churches established missions in Malawi, such as the St Michael and All Angels Church in Blantyre founded in 1876. The target once again were the Yao Muslims who had embraced Islam earlier than the 1870s. By the time the Established Church of Scotland came to Malawi, they found chief Kapeni a Yao Muslim ruling what is known as Blantyre today. It was Kapeni who gave the missionaries land to establish the said St Michael and All Angels Church. Many of Amangochi Yao of Kapeni succumbed to the pressure of the Christian influence and they became Christians such as chief Machinjiri, Kumtumanjia and others. One of the alleged objectives of the missionaries was to end the slave trade in Malawi that continued until the end of the 19th century. However, the hidden intention of Livingstone was to colonise Central Africa (see The Missionaries by Moorhouse). This was achieved through the influence of the church and later on the defeat of powerful Yao and Ngoni chiefs in the 1890s. In 1878, a number of traders, mostly from Glasgow, formed the African Lakes Company to supply goods and services to the missionaries. Other missionaries, traders, hunters, and planters soon followed.

Before the Established church of Scotland established a mission among the Yao of Kapeni 1876, another Scottish group of the Free Church of Scotland had secured land from the Machinga Yao chief Mponda in Mangochi. In 1875 chief Mponda gave land to Robert Laws. As a result, Laws opened a mission among the Islamised Yao in Mangochi. The mission station survived in the first years because food was plentiful in the Mponda and Makanjila areas. The chiefs of the said areas practiced commercial farming. However, the missionaries for six years failed to convert the Machinga Yao. However, Mangochi Yao of upper Shire such those found in Zomba and Blantyre embraced Christianity.

In 1889 the Catholic White Fathers also aimed to convert the Yao of Mponda in Mangochi. Chief Mponda gave them land to open a mission station. The influence of the Catholics has been strong since 1889. The Church had been trying its best to Christianise the Yao by building schools and a clinic every four kilometres in Mangochi. At present the Church has Radio Maria, a major seminary and the university in the district.

British rule

.svg.png.webp)

In 1883, a consul of the British Government was accredited to the "Kings and Chiefs of Central Africa" and in 1891, the British established the British Central Africa Protectorate.

In 1907 the name was changed to Nyasaland or the Nyasaland Protectorate (Nyasa is the Chiyao word for "lake"). In the 1950s, Nyasaland was joined with Northern and Southern Rhodesia in 1953 to form the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. The Federation was dissolved on 31 December 1963.

In January 1915, John Chilembwe, a Millenarian pastor in south-eastern Nyasaland, led an unsuccessful revolt, known as the Chilembwe uprising, against British rule. Chilembwe opposed the recruitment of Nyasas in the British army's campaign in East Africa, as well as the system of colonial rule. Chilembwe's followers attacked local plantations, but were soon defeated by British forces. Chilembwe was killed, and many of his followers were executed.

In 1944, the Nyasaland African Congress (NAC), inspired by the African National Congress' Peace Charter of 1914, emerged. NAC soon spread across Southern African with powerful branches emerging among migrant Malawian workers in Salisbury (now Harare) in Southern Rhodesia and Lusaka, in Northern Rhodesia.

Thousands of Nyasalanders fought in the Second World War.

In July 1958, Dr Hastings Kamuzu Banda returned to the country after a long absence in the United States, the United Kingdom and Ghana. He assumed leadership of the NAC, which later became the Malawi Congress Party (MCP). In 1959, Banda was sent to Gwelo Prison for his political activities but was released in 1960 to participate in a constitutional conference in London.

In August 1961, the MCP won an overwhelming victory in an election for a new Legislative Council. It also gained an important role in the new Executive Council and ruled Nyasaland in all but name a year later. In a second constitutional conference in London in November 1962, the British Government agreed to give Nyasaland self-governing status the following year.

Hastings Banda became Prime Minister on 1 February 1963, although the British still controlled the country's financial, security, and judicial systems. A new constitution took effect in May 1963, providing for virtually complete internal self-government.

Independence

Malawi became a fully independent member of the Commonwealth (formerly the British Commonwealth) on 6 July 1964.

Shortly after, in August and September 1964, Banda faced dissent from most of his cabinet ministers in the Cabinet Crisis of 1964. The Cabinet Crisis began with a confrontation between Banda, the Prime Minister, and all the cabinet ministers present on 26 August 1964. Their grievances were not dealt with, but three cabinet ministers were dismissed on 7 September. These dismissals were followed, on the same day and on 9 September, by the resignations of three more cabinet ministers in sympathy with those dismissed, although one of those who had resigned rescinded his resignation within a few hours. The reasons that the ex-ministers put forward for the confrontation and their subsequent resignations were the autocratic attitude of Banda, who failed to consult other ministers and kept power in his own hands, his insistence on maintaining diplomatic relations with South Africa and Portugal and a number of domestic austerity measures. After continuing unrest and some clashes between their supporters and those of Banda, most of the ex-ministers left Malawi in October. One ex-minister, Henry Chipembere led a small, unsuccessful armed uprising in February 1965. After its failure, he arranged for his transfer to the USA. Another ex-minister, Yatuta Chisiza, organised an even smaller incursion from Mozambique in 1967, in which he was killed. Several of the former ministers died in exile or, in the case of Orton Chirwa in a Malawian jail, but some survived to return to Malawi after Banda was deposed in 1993, and resumed public life.

Two years later, Malawi adopted a republican constitution and became a one-party state with Hastings Banda as its first president.

One-party rule

In 1970, Hastings Banda was declared President for life of the MCP, and in 1971 Banda consolidated his power and was named President for life of Malawi itself. The paramilitary wing of the Malawi Congress Party, the Young Pioneers, helped keep Malawi under totalitarian control until the 1990s.[9][10][11]

Banda, who was always referred to as "His Excellency the Life President Ngwazi Dr. H. Kamuzu Banda", was a dictator. Allegiance to him was enforced at every level. Every business building was required to have an official picture of Banda hanging on the wall. No other poster, clock, or picture could be placed higher on the wall than the president's picture. The national anthem was played before most events – including movies, plays, and school assemblies. At the cinemas, a video of His Excellency waving to his subjects was shown while the anthem played. When Banda visited a city, a contingent of women was expected to greet him at the airport and dance for him. A special cloth, bearing the President's picture, was the required attire for these performances. The one radio station in the country aired the President's speeches and government propaganda. People were ordered from their homes by police, and told to lock all windows and doors, at least an hour prior to President Banda passing by. Everyone was expected to wave.

Among the laws enforced by Banda, it was illegal for women to wear see-through clothes, pants of any kind or skirts which showed any part of the knee. There were two exceptions to this: if they were at a Country Club (a place where various sports were played) and if they were at a holiday resort/hotel, which meant that with the exception of the resort/hotel staff they were not seen by the general populace. Men were not allowed to have hair below the collar; when men whose hair was too long arrived in the country from overseas, they were given a haircut before they could leave the airport. Churches had to be government sanctioned. Members of certain religious groups, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, were persecuted and forced to leave the country at one time. All Malawian citizens of Indian heritage were forced to leave their homes and businesses and move into designated Indian areas in the larger cities. At one time, they were all told to leave the country, then hand-picked ones were allowed to return. It was illegal to transfer or take privately earned funds out of the country unless approved through proper channels; proof had to be supplied to show that one had already brought in the equivalent or more in foreign currency in the past. When some left, they gave up goods and earnings.

All movies shown in theatres were first viewed by the Malawi Censorship Board. Content considered unsuitable – particularly nudity or political content – was edited. Mail was also monitored by the Censorship Board. Some overseas mail was opened, read, and sometimes edited. Videotapes had to be sent to the Censorship Board to be viewed by censors. Once edited, the movie was given a sticker stating that it was now suitable for viewing, and sent back to the owner. Telephone calls were monitored and disconnected if the conversation was politically critical. Items to be sold in bookstores were also edited. Pages, or parts of pages, were cut out or blacked out of magazines such as Newsweek and Time.

While Malawi was a middle income country in the world during much of Banda's tenure, he managed to keep peace in the country for most of the time he was in power. He was a wealthy man, like most if not all world leaders. He owned houses (and lived in a palace), businesses, private helicopters, cars and other such luxuries. Speaking out against the President was strictly prohibited. Those who did so were often deported or imprisoned. Banda and his government were criticised for human rights violations by Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International. After he was deposed, Banda was put on trial for murder and attempts to destroy evidence.

During his rule, Banda was one of the very few post-colonial African leaders to maintain diplomatic relations with Apartheid-era South Africa.

Multi-party democracy

Increasing domestic unrest and pressure from Malawian churches and from the international community led to a referendum in which the Malawian people were asked to vote for either a multi-party democracy or the continuation of a one-party state. On 14 June 1993, the people of Malawi voted overwhelmingly in favour of multi-party democracy. Free and fair national elections were held on 17 May 1994 under a provisional constitution, which took full effect the following year.

Bakili Muluzi, leader of the United Democratic Front (UDF), was elected President in those elections. The UDF won 82 of the 177 seats in the National Assembly and formed a coalition government with the Alliance for Democracy (AFORD). That coalition disbanded in June 1996, but some of its members remained in the government. The President was referred to as Dr Muluzi, having received an honorary degree at Lincoln University in Missouri in 1995. Malawi's newly written constitution (1995) eliminated special powers previously reserved for the Malawi Congress Party. Accelerated economic liberalisation and structural reform accompanied the political transition.

On 15 June 1999, Malawi held its second democratic elections. Bakili Muluzi was re-elected to serve a second five-year term as President, despite an MCP-AFORD Alliance that ran a joint slate against the UDF.

The aftermath of elections brought the country to the brink of civil strife. Disgruntled Tumbuka, Ngoni and Nkhonde Christian tribes dominant in the north were irritated by the election of Bakili Muluzi, a Muslim from the south. Conflict arose between Christians and Muslims of the Yao tribe (Muluzi's tribe). Property valued at over millions of dollars was either vandalised or stolen and 200 mosques were torched down.[12]

Malawi in the 21st century

In 2001, the UDF held 96 seats in the National Assembly, while the AFORD held 30, and the MCP 61. Six seats were held by independents who represent the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) opposition group. The NDA was not recognised as an official political party at that time. The National Assembly had 193 members, of whom 17 were women, including one of the Deputy Speakers.

Malawi saw its very first transition between democratically elected presidents in May 2004, when the UDF's presidential candidate Bingu wa Mutharika defeated MCP candidate John Tembo and Gwanda Chakuamba, who was backed by a grouping of opposition parties. The UDF, however, did not win a majority of seats in Parliament, as it had done in 1994 and 1999 elections. It successfully secured a majority by forming a "government of national unity" with several opposition parties. Bingu wa Mutharika left the UDF party on 5 February 2005 citing differences with the UDF, particularly over his anti-corruption campaign. He won a second term outright in the 2009 election as the head of a newly founded party, the Democratic Progressive Party.

See also

- Heads of Government of Malawi

- History of Africa

- History of Southern Africa

- List of heads of state of Malawi

- Politics of Malawi

- Lilongwe history and timeline

References

- MacKenzie, John M. (June 2013). "A History of Malawi, 1859–1966". The Round Table. 102 (3): 312–314. doi:10.1080/00358533.2013.793568. ISSN 0035-8533. S2CID 153375208.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 5 October 2012. Retrieved 22 June 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Nurse, G. T. (July 1967). "The Name "Akafula"". The Society of Malawi Journal. 20 (2): 17–22. JSTOR 29778159.

- The History of Southern Africa, edited by Amy McKenna (Britannica Educational Publishing, 2011), p. 101.

- Excerpts from António Bocarro's "Livro do Estado da Índia" in George McCall Theal (ed.), Records of South-Eastern Africa, vol. 3 (Cape Town, 1899), pp. 254–435.

- R. A. Hamilton, "The Route of Gaspar Bocarro from Tete to Kilwa in 1616", The Nyasaland Journal, 7:2 (1954), pp. 7-14.

- Z. Claude Chidzero – 'The Lomwe Diaspora and Settlement on Tea Estates in Thyolo, Southern Malawi', Degree Research paper, History Department, University of Malawi, Zomba, 1981

- McCracken, John, 1938- author. (2012). A history of Malawi, 1859-1966. ISBN 978-1-84701-064-3. OCLC 865575972.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- https://www.britannica.com/biography/Hastings-Kamuzu-Banda

- https://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/the-cult-of-hastings-banda-takes-hold/article4273860/

- https://academic.oup.com/afraf/article-abstract/97/387/231/16549?redirectedFrom=fulltext

- http://www.islamonline.net/servlet/Satellite?c=Article_C&cid=1235628763190&pagename=Zone-English-News/NWELayout Archived 7 March 2009 at the Wayback Machine

Bibliography

- S.S. Murray, A Handbook of Nyasaland

- Valiant Mussa, History of Islam in Malawi before and after Christianity

- Leroy Vail and Landeg White (eds). Tribalism in the Political History of Malawi