History of Cameroon

Part of a series on the |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Cameroon | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Pre-colonial | ||||||||||

| Colonial | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

| Post-colonial | ||||||||||

|

||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

Early history

The earliest inhabitants of Cameroon were probably the Baka (Pygmies). They still inhabit the forests of the south and east provinces.[1] Bantu speakers originating in the Cameroonian highlands were among the first groups to move out before other invaders.

The Mandara kingdom in the Mandara Mountains was founded around 1500 and erected fortified structures, the purpose and exact history of which are still unresolved. The Aro Confederacy of Nigeria had a presence in Western (later called British) Cameroon due to trade and migration in the 18th and 19th centuries.

During the late 1770s and the early 19th century, the Fulani, an Islamic pastoral people of the western Sahel, conquered most of what is now northern Cameroon, subjugating or displacing its largely non-Muslim inhabitants.

Although the Portuguese arrived on Cameroon's doorstep in the 16th century, malaria prevented significant European settlement and conquest of the interior until the late 1870s, when large supplies of the malaria suppressant quinine became available. The early European presence in Cameroon was primarily devoted to coastal trade and the acquisition of slaves. The northern part of the country was an important part of the Muslim slave trade network. The trade was largely suppressed by the mid-19th century. Christian missionaries established a presence in the late 19th century and continue to play a role in Cameroonian life.

Colonization

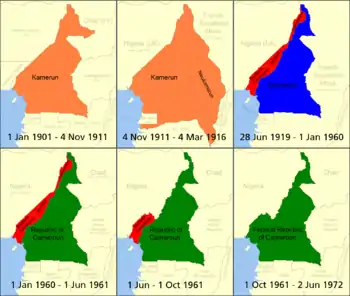

Beginning on July 5, 1884, all of present-day Cameroon and parts of several of its neighbours became a German colony, Kamerun, with a capital first at Buea and later at Yaoundé.

Germany was particularly interested in Cameroon's agricultural potential and entrusted large firms with the task of exploiting and exporting it. German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck defined the order of priorities as follows: "first the merchant, then the soldier". It was under the influence of a businessman Adolph Woermann, whose company set up a trading house in Douala, that Bismarck, initially skeptical about the interest of the colonial project, was convinced. Large German trading companies (Woermann, Jantzen & Thormählen) and concession companies (Südkamerun Gesellschaft, Nord-West Kamerun Gesellschaft) established themselves massively in the colony. Letting the big companies impose their order, the administration simply supported them, protected them and tried to eliminate indigenous rebellions.[2]

The imperial German government made substantial investments in the infrastructure of Cameroon, including the extensive railways, such as the 160-metre single-span railway bridge on the southern branch of Sanaga River. However, the indigenous peoples proved reluctant to work on these projects, so the Germans instigated a harsh and unpopular system of forced labour.[3] In fact, Jesko von Puttkamer was relieved of duty as governor of the colony due to his untoward actions toward the native Cameroonians.[4] In 1911 at the Treaty of Fez after the Agadir Crisis, France ceded a nearly 300,000 km2 portion of the territory of French Equatorial Africa to Kamerun which became Neukamerun (New Cameroon), while Germany ceded a smaller area in the north in present-day Chad to France.

In World War I, the British invaded Cameroon from Nigeria in 1914 in the Kamerun campaign, with the last German fort in the country surrendering in February 1916. After the war, this colony was partitioned between the United Kingdom and France under June 28, 1919 League of Nations mandates (Class B). France gained the larger geographical share, transferred Neukamerun back to neighboring French colonies, and ruled the rest from Yaoundé as Cameroun (French Cameroons). Britain's territory, a strip bordering Nigeria from the sea to Lake Chad, with an equal population was ruled from Lagos as Cameroons (British Cameroons). German administrators were allowed to once again run the plantations of the southwestern coastal area. A British parliamentary publication, Report on the British Sphere of the Cameroons (May 1922, p. 62-8), reported that the German plantations there were "as a whole . . . wonderful examples of industry, based on solid scientific knowledge. The natives have been taught discipline and have come to realize what can be achieved by industry. Large numbers who return to their villages take up cocoa or other cultivation on their own account, thus increasing the general prosperity of the country."

La République du Cameroun

The French administration, reluctant to return their pre-war possessions to German companies, reassigned some of them to French companies. This was particularly the case for the Société financière des caoutchoucs, which obtained plantations put into operation during the German period and became the largest company in Cameroon under French mandate. Roads were being built to link the main cities together, as well as various infrastructure such as bridges and airports. The Douala-Yaoundé railway line, begun under the German regime, had been completed. Thousands of workers were forcibly deported to this site to work fifty-four hours a week. Workers also suffered from lack of food and the massive presence of mosquitoes. In 1925, the mortality rate on the site was 61.7%. However, the other sites were not as deadly, although working conditions were generally very harsh.[2]

French Cameroon joined the Free France in August 1940. The system established by Free France was similar to a military dictatorship. Philippe Leclerc de Hauteclocque established a state of siege throughout the country and abolished almost all public freedom. The objective was to neutralize any potential feelings of independence or sympathy for the former German colonizer. Indigenous people known for their Germanophilia were executed in public places. In 1945, the country was placed under the supervision of the United Nations. Despite this, in 1946 it became an "associated territory" of the French Union.

Towards independence of La République du Cameroun (1955–1960)

In 1948, the Union des populations du Cameroun (UPC), a nationalist movement, was founded and Ruben Um Nyobe took over as its leader. In May 1955, the arrests of independence activists were followed by riots in several cities across the country. The repression caused several dozen (the French administration officially lists twenty-two, although secret reports acknowledge many more) or hundreds of deaths. The UPC was banned and nearly 800 of its activists were arrested, many of whom would be beaten in prison. Because they were wanted by the police, UPC activists took refuge in the forests, where they formed maquis; they also took refuge in neighboring British Cameroon. The French authorities repressed these events and made arbitrary arrests. The party received the support of personalities such as Gamal Abdel Nasser and Kwame Nkrumah and France's action was denounced at the UN by representatives of countries such as India, Syria and the Soviet Union.[2]

An insurrection broke out among the Bassa people on the 18 to 19 December 1956: several dozen anti-UPC figures were murdered or kidnapped, bridges, telephone lines and other infrastructure were sabotaged. Units of the Cameroonian guard violently repressed these events, which led to the rallying of the peasants to the maquis. Several UPC maquis were formed with their "generals" and "captains" leading "regiments" (150–200 guerrillas) and "battalions" (50 guerrillas). The weapons were very basic: a few stolen guns and pistols, but mainly machetes, clubs, bows, and arrows. To isolate the rebellion from the Bassa civilian population, who were suspected of being particularly independentists, they were deported to camps along the main roads. General Lamberton, in charge of the French forces, ordered: "Any huts or installations remaining outside the assembly areas must be completely razed and their surrounding crops destroyed. "Villagers were subjected to forced labor on behalf of Razel, particularly in road construction. The Bassa living in the city were expelled to their region of origin to prevent the "virus of protest" from spreading. This rebellion continued, with diminishing intensity, even after independence until 1961.[5] Some tens of thousands died during this conflict.[6][7]

Legislative elections were held on 23 December 1956 and the resulting Assembly passed a decree on 16 April 1957 which made French Cameroon a state. It took back its former status of associated territory as a member of the French Union. Its inhabitants became Cameroonian citizens, and Cameroonian institutions were created under a parliamentary democracy. On 12 June 1958, the Legislative Assembly of French Cameroon asked the French government to: "Accord independence to the State of Cameroon at the ends of their trusteeship. Transfer every competence related to the running of internal affairs of Cameroon to Cameroonians". On 19 October 1958, France recognized the right of her United Nations trust territory to choose independence.[8] On 24 October 1958, the Legislative Assembly of French Cameroon solemnly proclaimed the desire of Cameroonians to see their country accede full independence on 1 January 1960. It enjoined the government of French Cameroon to ask France to inform the General Assembly of the United Nations, to abrogate the trusteeship accord concomitant with the independence of French Cameroon.

On 12 November 1958, having accorded French Cameroon total internal autonomy and thinking that this transfer no longer permitted it to assume its responsibilities over the trust territory for an unspecified period, the government of France asked the United Nations to grant the wish of French Cameroonians. On 5 December 1958, the United Nations’ General Assembly took note of the French government's declaration according to which French Cameroon, which was under French administration, would gain independence on 1 January 1960, thus marking an end to the trusteeship period.[9][10] On 13 March 1959, the United Nations’ General Assembly resolved that the UN Trusteeship Agreement with France for French Cameroon would end when French Cameroon became independent on 1 January 1960.[11]

British Cameroon

The area of present-day Cameroon was claimed by Germany as a protectorate during the "Scramble for Africa" at the end of the 19th century. The German Empire named the territory Kamerun.

League of Nations Mandate

During the First World War, it was occupied by British, French and Belgian troops, and a later League of Nations Mandate to Great Britain and France by the League of Nations in 1922. The French mandate was known as Cameroun and the British territory was administered as two areas, Northern Cameroons and Southern Cameroons. Northern Cameroons consisted of two non-contiguous sections, divided by a point where the Nigerian and Cameroun borders met. In the 1930s, most of the white population consisted of Germans, which were interned in British camps starting in June 1940. The native population of 400,000 showed little interest in volunteering for the British forces; only 3,500 men did so.[12]

Trust territory

When the League of Nations ceased to exist in 1946, most of the mandate territories were reclassified as UN trust territories, henceforth administered through the UN Trusteeship Council. The object of trusteeship was to prepare the lands for eventual independence. The United Nations approved the Trusteeship Agreements for British Cameroons to be governed by Britain on 6/12/ 1946.

Independence

French Cameroun became independent, as Cameroun or Cameroon, in January 1960, and Nigeria was scheduled for independence later that same year, which raised question of what to do with the British territory. After some discussion (which had been going on since 1959), a plebiscite was agreed to and held on 11 February 1961. The Muslim-majority Northern area opted for union with Nigeria, and the Southern area voted to join Cameroon.[13]

Northern Cameroons became the Sardauna Province of Northern Nigeria[14] on 31 May 1961, while Southern Cameroons became West Cameroon, a constituent state of the Federal Republic of Cameroon, later that year on 1 October 1961.

Cameroon after independence

.svg.png.webp)

French Cameroon achieved independence on January 1, 1960 as La République du Cameroun. After Guinea, it was the second of France's colonies in Sub-Saharan Africa to become independent. On 21 February 1960, the new nation held a constitutional referendum. On 5 May 1960, Ahmadou Ahidjo became president. On 11 February 1961, a plebiscite organised by the United Nations was held in the British controlled part of Cameroon (British Northern and British Southern Cameroons). The pleibiscite was to choose between free association with an independent Nigerian state or re-unification with the independent Republic of Cameroun. On 12 February 1961,the results of the plebiscite were released and British Northern Cameroons attached itself to Nigeria, while the southern part voted for reunification with the Republic Of Cameroon. To negotiate the terms of this union, the Foumban Conference was held on 16–21 July 1961. John Ngu Foncha, the leader of the Kamerun National Democratic Party . The British Southern Cameroons was to be referred to as West Cameroon and the French part as East Cameroon. Buea became the capital of the now West Cameroon while Yaounde doubled as the federal capital and East Cameroon. Ahidjo accepted the federation, thinking it was a step towards a unitary state. On 14 August 1961, the federal constitution was adopted, with Ahidjo as president. Foncha became the prime minister of west Cameroon and vice president of the Federal Republic of Cameroon. On 1 September 1966 the Cameroon National Union (CNU) was created by the union of political parties of East and West Cameroon. Most decisions about West Cameroon were taken without consultation, which led to widespread feelings amongst the West Cameroonian public that although they voted for reunification, what they were getting is absorption or domination".[15]

During the first years of the regime, the French ambassador Jean-Pierre Bénard is sometimes considered as the true "president" of Cameroon. This independence is indeed largely theoretical since French "advisers" are responsible for assisting each minister and have the reality of power. The Gaullist government preserves its influence over the country through the signing of "cooperation agreements" covering all sectors of Cameroon's sovereignty. Thus, in the monetary field, Cameroon retains the CFA franc and entrusts its monetary policy to its former guardian power. All strategic resources are exploited by France, French troops are maintained in the country, and a large proportion of Cameroonian army officers are French, including the Chief of Staff.[2]

On October 1, 1961, the largely Muslim northern two-thirds of British Cameroons voted to join Nigeria; the largely Christian southern third, Southern Cameroons, voted, in a referendum, to join with the Republic of Cameroon to form the Federal Republic of Cameroon. The formerly French and British regions each maintained substantial autonomy. Ahidjo was chosen president of the federation in 1961. In 1962, the Francs CFA became the official currency in Cameroon.

The authorities are multiplying the legal provisions enabling them to free themselves from the rule of law: arbitrary extension of police custody, prohibition of meetings and rallies, submission of publications to prior censorship, restriction of freedom of movement through the establishment of passes or curfews, prohibition for trade unions to issue subscriptions, etc. Anyone accused of "compromising public safety" is deprived of a lawyer and cannot appeal the judgment. Sentences of life imprisonment at hard labour or death penalty – executions can be public – are thus numerous. A one-party system was introduced in 1966.[2]

Ahidjo successfully suppressed the continuing UPC rebellion, capturing the last important rebel leader in 1970. On 28 March 1970 Ahidjo renewed his mandate as the supreme magistracy; Solomon Tandeng Muna became vice president. In 1972, a new constitution replaced the federation with a unitary state called the United Republic of Cameroon. Although Ahidjo's rule was characterised as authoritarian, he was seen as noticeably lacking in charisma in comparison to many post-colonial African leaders. He didn't follow the anti-western policies pursued by many of these leaders, which helped Cameroon achieve a degree of comparative political stability and economic growth.

Cameroon became an oil-producing country in 1977. Claiming to want to make reserves for difficult times, the authorities manage "off-budget" oil revenues in total opacity (the funds are placed in Paris, Switzerland and New York accounts). Several billion dollars are thus diverted to the benefit of oil companies and regime officials. The influence of France and its 9,000 nationals in Cameroon remains considerable. African Affairs magazine noted in the early 1980s that they "continue to dominate almost all key sectors of the economy, much as they did before independence. French nationals control 55% of the modern sector of the Cameroonian economy and their control over the banking system is total[2]

On 30 June 1975 Paul Biya was appointed vice president. Ahidjo resigned as president in 1982 and was constitutionally succeeded by his Prime Minister, Paul Biya, a career official. Ahidjo later regretted his choice of successors, but his supporters failed to overthrow Biya in a 1984 coup. Biya won single-candidate elections in 1983 and 1984 when the country was again named the Republic of Cameroon. Biya has remained in power, winning flawed multiparty elections in 1992, 1997, 2004 and 2011. His Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (CPDM) party holds a sizeable majority in the legislature.

By April 6, 1984, the country witnessed its first coup d'état headed by col. Issa Adoum. At about 3 am rebel forces mostly of the Republican guard under the orders of colonel Ibrahim Saleh, attempted to unseat Biya's government. The rebels took charge of the Yaounde airport, national radio station and announced the takeover of government. They attacked the presidency. The civilian northerner who was manager of FONADER Issa Adoum was expected to become the new interim president. Unfortunately, many reasons led to its failure. The principal coup plotters had been arrested by April 10, 1984 and President Biya addressed the nation that calm had been restored.

On August 15, 1984, Lake Monoun exploded in a limnic eruption that released carbon dioxide, suffocating 37 people to death. On August 21, 1986, another limnic eruption at Lake Nyos killed as many as 1,800 people and 3,500 livestock. The two disasters are the only recorded instances of limnic eruptions.

In May 2014, in the wake of the Chibok schoolgirl kidnapping, Presidents Paul Biya of Cameroon and Idriss Déby of Chad announced they were waging war on Boko Haram, and deployed troops to the Nigerian border.[16][17]

In early 2006 a final resolution to the dispute between Cameroon and Nigeria over the oil-rich Bakassi peninsula was expected. In October 2002, the International Court of Justice had ruled in favour of Cameroon. Nonetheless, a lasting solution would require agreement by both countries’ presidents, parliaments, and by the United Nations. The peninsula was the site of fighting between the two countries in 1994 and again in June 2005, which led to the death of a Cameroonian soldier. In 2006, Nigerian troops left the peninsula.

In 2014, the Boko Haram insurgency spread into Cameroon from Nigeria. Cameroon announced in September 2018 that Boko Haram had been repelled, but the conflict persists in the northern border areas nonetheless.[18]

In November 2016, major protests broke out in the Anglophone regions of Cameroon. In September 2017, the protests and the government's response to them escalated into an armed conflict, with separatists declaring the independence of Ambazonia and starting a guerilla war against the Cameroonian Army.

Football

Cameroon has received some international attention following the relative success of its football team. It has qualified for the FIFA World Cup on a number of occasions. Its most notable performance was at Italia 90, when the team beat Argentina, the then reigning Champions in the opening game; Cameroon eventually lost in extra time in the Quarterfinals to England.

See also

- Ambazonia

- History of Africa

- Politics of Cameroon

- List of heads of government of Cameroon

- List of heads of state of Cameroon

- Douala history and timeline

- Yaoundé history and timeline

References

- Background Note: Cameroon from the U.S. Department of State.

- Bullock, A. L. C. (1939). Germany's Colonial Demands, Oxford University Press.

- DeLancey, Mark W., and DeLancey, Mark Dike (2000): Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Cameroon (3rd ed.). Lanham, Maryland: The Scarecrow Press.

- Schnee, Heinrich (1926). German Colonization, Past and Future: The Truth about the German Colonies. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Notes

- "About.com".

- Thomas Deltombe, Manuel Domergue, Jacob Tatsita, Kamerun !, La Découverte, 2019

- DeLancey and DeLancey 125.

- DeLancey and DeLancey 226.

- "8. British/French Cameroon (1948–1961)".

- Eckhardt, William, in World Military and Social Expenditures 1987–88 (12th ed., 1987) by Ruth Leger Sivard.

- The Cambridge History of Africa (1986), ed. J. D. Fage and R. Oliver

- Brady, Thomas F. (20 October 1958). "CAMEROONS GETS FREEDOM PLEDGE; Paris Backs Independence for African Trust Territory After Interim Self-Rule" – via NYTimes.com.

- "From trusteeship to independence (1946–1960)". Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 2011-12-30.CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link)

- "Question of the future of the Trust Territories of the Cameroons under French administration and the Cameroons under United Kingdom administration". undocs.org. United Nations. A/RES/1282(XIII). Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- "The future of the Trust Territories of the Cameroons under French administration". undocs.org. United Nations. A/RES/1349(XIII). Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- I.C.B Dear, ed, The Oxford Companion to World War II (1995) p 163

- Nohlen, D, Krennerich, M & Thibaut, B (1999) Elections in Africa: A data handbook, p177 ISBN 0-19-829645-2

- Parties and Politics in Northern Nigeria, Routledge, 1968, page 155

- The Untold Story of Reunification: (1955–1961)

- "Cameroon, Chad Deploy Troops to Fight Boko Haram – Nigeria". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- Kaze, Rennier (2014-06-06). "Dans le Nord du Cameroun, la "guerre" contre Boko Haram a commencé – Cameroon". ReliefWeb (in French). Retrieved 2014-06-10.

- Boko Haram has been repelled, Cameroon's leader declares, CBC, Sep 30, 2018. Accessed Feb 6, 2019.

External links

![]() Media related to History of Cameroon at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to History of Cameroon at Wikimedia Commons

- Map of German Cameroon (Kamerun) in 1914 at the Wayback Machine (archived 4 April 2013)