History of Gwynedd during the High Middle Ages

The history of Gwynedd in the High Middle Ages is a period in the History of Wales spanning the 11th through the 13th centuries. Gwynedd, located in the north of Wales, eventually became the most dominant of Welsh principalities during this period. Distinctive achievements in Gwynedd include further development of Medieval Welsh literature, particularly poets known as the Beirdd y Tywysogion (Welsh for Poets of the Princes) associated with the court of Gwynedd; the reformation of bardic schools; and the continued development of Cyfraith Hywel (The Law of Hywel, or Welsh law). All three of these further contributed to the development of a Welsh national identity in the face of Anglo-Norman encroachment of Wales.

Gwynedd's traditional territory included Anglesey (Ynys Môn) and all of north Wales between the River Dyfi in the south and River Dee (Welsh Dyfrdwy) in the northeast.[1] The Irish Sea (Môr Iwerddon) lies to the north and west, and lands formerly part of the Powys border the south-east. Gwynedd's strength was due in part to the region's mountainous geography which made it difficult for foreign invaders to campaign in the country and impose their will effectively.[2]

Gwynedd emerged from the Early Middle Ages having suffered from increasing Viking raids and various occupations by rival Welsh princes, causing political and social upheaval. With the historic Aberffraw family displaced, by the mid 11th century Gwynedd was united with the rest of Wales by the conquest of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, followed by the Norman invasions between 1067 and 1100.

After the restoration of the Aberffraw family in Gwynedd, a series of successful rulers such as Gruffudd ap Cynan, Owain Gwynedd, Llywelyn the Great and his grandson Llywelyn ap Gruffudd led to the emergence of the Principality of Wales, based in Gwynedd.[3] The emergence of the principality in the 13th century was proof that all the elements necessary for the growth of Welsh statehood independent of England were in place.[4] As part of the Principality of Wales, Gwynedd would retain Welsh laws and customs and home rule until the Edwardian Conquest of Wales of 1282.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Wales |

|

|

|

History

Norse raids; Aberffraw dispossessed

.svg.png.webp)

The latter part of the 10th century, and the whole of the 11th century, was an exceptionally tumultuous period for the Gwyneddwyr, Gwynedd's Welsh populace.[5] Deheubarth's ruler Maredudd ab Owain deposed Gwynedd's ruler Cadwallon ab Ieuaf of the House of Aberffraw in 986, annexing Gwynedd to his enlarged domain, which came to include most of Wales.[5]

The Hiberno-Norse from Dublin and the Isle of Man routinely raided the coasts of Wales, with the Welsh people of Ynys Môn and the Llŷn Peninsula suffering the most in Gwynedd.[5] In 987 a Norse raiding party landed on Môn and captured as many as two thousand of the island's residents, selling them as slaves across northern Europe.[5] Historian and author Dr. John Davies argues that it is during this period that the Norse name for Môn, Anglesey, came into existence; it was later adopted into English.[5][6] In 989 Meredudd ab Owain bribed the Norse not to raid that year. However the Norse resumed significant raids on Môn in 993, as well as on other parts of Wales for the remainder of the century.[5]

In 999 Meredudd ab Owain of Deheubarth died, and Cynan ap Hywel was able to wrestle back Gwynedd for the Aberffraw dynasty.[7] However, Cynan himself was deposed by Aeddan ap Blegywryd in 1005.[7] Aeddan was not himself connected to the Aberffraw family, and was perhaps a minor commote lord.[7] Aeddan ruled Gwynedd until 1018, when he and his four sons were defeated in battle by Llywelyn ap Seisyll, lord of Rhuddlan in lower Gwynedd.[7][8][9][10]

Llywelyn ap Seisyll married Anghared, daughter of Meredudd ab Owain of Deheubarth, and ruled Gwynedd until his death in 1023, when Iago ab Idwal recovered the rulership of Gwynedd for the senior line of the Aberffraw house. Iago reigned over Gwynedd until 1039, when he was murdered by his own men, perhaps under the direction of Gruffydd of Rhuddlan, Llywelyn ap Seisyll's eldest son.[8]

At age four, the Aberffraw heir Cynan ab Iago escaped with his mother to exile in Dublin.

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn; 1039–1063

Gruffydd ap Llywelyn seized control of Gwynedd in 1039 with the death of Iago ab Idwal and, after taking possession of Powys, struck at Mercia, slaying Edwin of Mercia, brother of Leofric, Earl of Mercia.[11] Gruffydd's decisive defeat of the Mercians in battle at Rhyd y Groes on the Severn (location unknown) neutralised Mercian incursions on Gwynedd and Powys' eastern borders as many of Mercia's leading magnates were also slain alongside Edwin of Mercia.[11]

Conquest of south Wales

Gruffydd then turned his attention to the conquest of Deheubarth, ruled by his maternal cousin Hywel ab Edwin of the House of Dinefwr. The latter was "by no means easy to dislodge", wrote Lloyd.[11] Gruffydd raided Deheubarth's province of Ceredigion in 1036, ravaging the lands of the monastic community of Llanbadarn Fawr (Great Llanbadarn).[11] Hywel of Deheubarth was able to defend Deheubarth against Gruffydd's raids until he was defeated in 1041 at the Battle of Pencader, after which Gruffydd captured Hywel's wife and became master of Ceredigion.[11] Following the Battle of Pencader, Hywel retained Dyfed (Pembrokeshire) and Ystrad Tywi (Carmarthenshire), the heart of Deheubarth. However he was expelled by Gruffydd in 1043 after an unrecorded event, and sought refuge in Ireland.[11] In 1044 Hywel returned to recover Deheubarth with an army of Hiberno-Norse, but was slain and defeated in the Battle of Aber Tywi by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn.[11]

Between 1044 and 1055 Gruffydd ap Llywelyn fought Gruffydd ap Rhydderch of Gwent for control of Deheubarth.[11] Following the defeat of Hywel by Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, Gruffydd ap Rhydderch of Gwent was able to "stir up" the minor commote lords of Deheubarth on his behalf, and to call up an army to resist Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, wrote Lloyd.[11] By 1046 Gruffydd ap Llywelyn allied with Sweyn Godwinson, Earl of Hereford, and the two of them campaigned in South Wales against Gruffydd of Gwent.[11] In 1047 the lords of Ystrad Tywi, the heart of Deheubarth and the seat of the Dinefwr family, led an army which totally defeated the 150-strong teulu, or household guard, of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, who was narrowly able to escape.[11] In retaliation against the resurgent nobles of Ystrad Tywi and Dyfed, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn devastated those provinces, but "in vain", wrote John Edward Lloyd, "as his authority in South Wales was ... shattered" by Gruffydd ap Rhydderch of Gwent who was now firmly in control of Ystrad Tywi and Dyfed.[11]

In the summer of 1052 Gruffydd ap Llywelyn raided the Norman settlements in Herefordshire in retaliation for the displacement of his former ally Sweyn Godwinson.[11] Sweyn Godwinson and his family were forced into exile and replaced by the Norman Ralph the Timid.[11] Gruffydd defeated the mixed force of Norman and English sent against his raiding party near Leominster. In 1055 Gruffydd ap Llywelyn defeated and killed his southern rival Gruffydd ap Rhydderch and took possession of Deheubarth, later driving out Meurig ap Hywel and Cadwagan ap Hywel of Gwent, and so becoming master over the whole of Wales.[11]

Wars with England

Gruffydd allied with Ælfgar, Earl of East Anglia (and son of Leofric, Earl of Mercia) who had been dispossessed of his earldom on charges of treason, charges which may or may not have been substantiated.[12]

On 24 October 1055, Gruffydd, Ælfgar, and Ælfgar's Hiberno-Norse mercenaries attacked the Norman settlement at Hereford, defeating Ralph, Earl of Hereford, and razing Hereford Castle.[12] In the looting which followed, Gruffydd and Ælfgar raided Hereford Cathedral of its rich vessels and furnishings, killing seven of the canons who sought to bar the cathedral doors against the raiders.[12]

Edward the Confessor, King of England, commissioned Harold Godwinson, Earl of Wessex, to respond to Gruffydd's raid on Hereford.[12] However Harold was unable to penetrate into Wales but for a few miles beyond the Dyffryn Dŵr (Valley of Dore).[12] A peace accord was reached between Gruffydd, Ælfgar, Harold of Wessex, and Edward the Confessor at Billingsley, near Boulston in Archenfield, with Ælfgar regaining his earldom of East Anglia.[12]

Despite the peace of Billingsley, cross border raids continued. In June 1056 Leofgar, Bishop of Hereford led an army into Wales in revenge for the earlier raid by Gruffydd and Ælfgar.[12][13] Gruffydd defeated Bishop Leofgar on 16 June in a battle in Dyffryn Machawy, with the bishop among those slain.[12] The following year the men of Hereford raised another army against the Welsh, but their army was dogged by skirmishes and defeat, and they were obliged to negotiate for a peace.[12]

King of Wales

.svg.png.webp)

Gruffydd and his "ever-victorious Welshmen", argued Lloyd, continued to pose a threat to the west of England.[12] In 1056, a treaty was reached between Gruffydd, master of Wales and the Welsh marches, and the leading magnates of England, who included Earl Harold Godwinson, Earl Leofric of Mercia, and Aldred of Worcester (soon to be Archbishop of York). Gruffydd would be recognised in all of his conquests if he would swear fealty to King Edward the Confessor, becoming an "under-king" in a similar manner to the King of Scots.[12] Agreeing to the terms, Gruffydd travelled from Chepstow to Gloucester where he and King Edward the Confessor met, and the treaty terms performed.[12]

From his family seat at Rhuddlan, Gruffydd ruled the whole of Wales as king.

Gruffydd's position as King of Wales was further strengthened in 1057 when his friend and ally, Ælfgar, Earl of East Anglia, inherited Mercia on the death of his father, Earl Leofric.[12] Their alliance was cemented by a dynastic marriage between Gruffydd and Ældyth, Ælfgar's daughter, around this time.[12] As allied neighbors, Gruffydd and Ælfgar were "fortified against all attack", argued Lloyd, as their territory included Gruffydd's Wales, and Ælfgar's Mercia and Anglia.[12]

However, Earl Ælfgar died in 1062 and was succeeded by his young and inexperienced son Edwin. The loss of a strong Mercian ruler exposed Gruffydd's position. Following King Edward's Christmas court held at Gloucester, "at a time most unusual for campaigning in Wales", noted Lloyd, Harold Godwinson led a small force of huscarls from Chester into Wales, boldly striking Gruffydd's court at Rhuddlan.[12] However Gruffydd received warning beforehand, and escaped on a small ship into the River Clwyd just as Harold's forces took Rhuddlan.[12]

Having failed to take Gruffydd in the winter of 1062, Harold Godwinson began preparations for a spring campaign in Wales.[12] Tostig Godwinson, Earl of Northumbria and Harold's brother, brought a force into North Wales aiming to conquer Ynys Môn, while Harold assembled a light infantry at Bristol, where they boarded ships sailing for North Wales.[12] On landing first in South Wales, and seeing the English army, the local magnates of Deheubarth came to terms with Harold and gave hostages as a guarantee of peace. Harold continued on to Gwynedd, where Gruffydd was already besieged by Tostig's army and "driven from one hiding place to another", wrote Lloyd.[12] Harold landed in Wales and joined in the hunt, and offered peace to the Welsh of Gwynedd in exchange for Gruffydd's head. Desperate to end the Anglo-Saxon siege, Gruffydd's own men murdered him on 5 August 1063.[12]

Following Gruffydd's death, Harold took Gruffydd's widow Ældyth of Mercia as his wife. Ældyth was the only woman to have been known as Queen of Wales and then Queen of England in turn.

Mathrafal ascendency and the Harrowing of the North; 1063–1081

Harold Godwinson did not undertake the conquest or occupation of Wales; there was not the planning or resources nor any national will to conquer Wales. Harold aimed at the elimination of any centralized authority in Wales.[12]

On his death, Gruffydd ap Llywelyn's maternal half brothers Bleddyn ap Cynfyn and Rhiwallon ap Cynfyn of the Mathrafal (pronounced Mathraval) house of Powys divided Gwynedd and Powys between them, swearing fealty to Edward the Confessor who endorsed their seizure, and with Deheubarth, Glamorgan, and Gwent returned to their historic dynasties.[14][15][16]

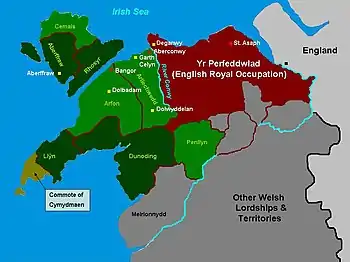

Bleddyn ap Cynfyn allied with the Anglo-Saxons of Northern England to resist the threat from William the Conqueror following the Norman Conquest of England in 1066.[15] In 1067 Bleddyn and Rhiwallon joined with the Mercian Eadric the Wild in an attack on the Normans at Hereford Castle, and ravaged the Norman lands in Herefordshire along the River Lugg, "causing serious damage" to the Normans, wrote Lloyd.[15] Between 1068 and 1070 Bleddyn allied with Edwin, Earl of Mercia, Gospatric, Earl of Northumbria and Morcar of Northumbria in an alliance against the Normans during the Harrowing of the North.[15] However the defeat of the Saxons in 1070 exposed lower Gwynedd, the Perfeddwlad, to Norman incursions, with Robert "of Rhuddlan" taking Rhuddlan Castle and establishing himself firmly at the mouth of the Clwyd river by 1073.[15]

Bleddyn was killed in 1075 by Rhys ab Owain, Prince of Deheubarth, an ally of the dispossessed Aberffraw heir of Gwynedd, Gruffudd ap Cynan, who was himself attempting to recover his inheritance.[15] Rhys ab Owain was able to recover Deheubarth for the House of Dinefwr following the death of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn in 1063. However, Trahaearn ap Caradog of Arwystli, Bleddyn's cousin, took control of Gwynedd and by 1078 defeated Rhys ab Owain at the Battle of Goodwick.[17] Trahaearn allied with Caradog ap Gruffydd of Gwent against Deheubarth.[17]

Gruffudd ap Cynan, who grew up in exile in Dublin and was himself half Hiberno-Norse on his mother's side, made his first attempt to recover Gwynedd in 1075 when he landed on Ynys Môn with a Norse force, and mercenary troops provided by Robert of Rhuddlan.[2] Gruffudd ap Cynan first defeated and killed Cynwrig ap Rhiwallon, an ally of Trahaearn who held Llŷn, then defeated Trahaearn himself in the Battle of Gwaed Erw in Meirionnydd, gaining control of Gwynedd.[17] Gruffudd then led his forces eastwards into lower Gwynedd, the Perfeddwlad, to recover lands lost to the Normans. Despite the "assistance" previously given by Robert of Rhuddlan, Gruffudd attacked and destroyed Rhuddlan castle. However, tension between Gruffudd's Hiberno-Norse bodyguard and the local Welsh led to a rebellion in Llŷn, and Trahaearn took the opportunity to counterattack, defeating Gruffudd at the Battle of Bron yr Erw, above Clynnog Fawr, that same year. Gruffudd retreated to Ireland but in 1081 returned and made an alliance with Rhys ap Tewdwr, the new Prince of Deheubarth following the death of his cousin. Rhys had been attacked by Caradog ap Gruffydd of Gwent and Morgannwg, and had been forced to flee from his fortress of Dinefwr to St David's Cathedral in Penfro (Pembrokeshire).

Leading Aberffraw partisans from Gwynedd and Norse-Gaelic mercenaries from Waterford, Ireland, Gruffudd joined his ally Rhys ap Tewdwr of Deheubarth, and the two marched their army north to seek out Trahaearn ap Caradog and Caradog ap Gruffydd of Powys, who had themselves made an alliance and been joined by Meilyr ap Rhiwallon of Morgannwg-Gwent. The armies of the two confederacies met at the Battle of Mynydd Carn, with Gruffudd and Rhys victorious and Trahaearn, Caradog and Meilyr all killed.[2][18] Gruffudd recovered Gwynedd for the second time.

Norman invasion, and the Aberffraw resistance; 1081–1100

Illustration by T. Prytherch in 1900

However, Gruffudd's victory was short-lived as the Normans launched an invasion of Wales following the Saxon revolt in northern England. Shortly after the Battle of Mynydd Carn in 1081, Gruffudd was lured into a trap with the promise of an alliance but seized by Hugh the Fat, 1st Earl of Chester in an ambush at Rug, near Corwen.[2][18][19] Earl Hugh claimed the Perfeddwlad up to the Clwyd river (the commotes of Tegeingl and Rhufoniog; the modern counties of Denbighshire, Flintshire and Wrexham) as part of Chester, and viewed the restoration of the Aberffraw family in Gwynedd as a threat to his own expansion into Wales.[18] The lands west of the Clwyd were intended for his cousin Robert of Rhuddlan, and their advance extended to the Llŷn peninsula by 1090.[18] Once in power, the Normans sought control over the spiritual traditions and ecclesiastical institutions in Wales.[20][21] In his effort further to consolidate control over Gwynedd, Earl Hugh of Chester had forced the election of Hervé the Breton upon the Bangor diocese in 1092, with Hervé's consecration as Bishop of Bangor performed by Thomas of Bayeux, the Archbishop of York.[21][22] It was hoped that placing a prelate loyal to the Normans over the traditionally independent Welsh Church in Gwynedd would help pacify the local inhabitants. However, the Welsh parishioners remained hostile to Hervé's appointment, and the bishop was forced to carry a sword with him and rely on a contingent of Norman knights for his protection.[23][24] Additionally, Hervé routinely excommunicated parishioners who he perceived as challenging his spiritual and temporal authority.[23]

By 1093 almost the whole of Wales was occupied by Norman forces and they erected many castles in an effort to consolidate their gains.[18] However, their control in most regions of Wales proved tenuous at best.[18] Motivated by local anger over the "gratuitously cruel" occupation, and led by the historic ruling houses such as Gwynedd's Aberffraw family, represented by Gruffudd ap Cynan, Welsh control over the greater part of Wales was restored by 1100.[18]

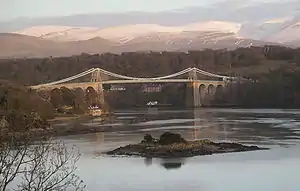

Gruffudd escaped Norman imprisonment in Chester, and slew Robert of Rhuddlan in a beach side battle at Deganwy on 3 July 1093.[19] The flag of revolt was raised across Wales in 1094, and William II of England was compelled to respond by leading two ultimately ineffective campaigns against Gruffudd in lower Gwynedd in 1095 and 1097. By 1098 Gruffudd allied with Cadwgan ap Bleddyn of the Mathrafal house of Powys, their traditional dynastic rivalries notwithstanding, with the two coordinating their resistance campaigns.[2] Earl Hugh of Chester and Hugh of Montgomery, 2nd Earl of Shrewsbury had greater success in their 1098 campaign against the Welsh, bringing their army to the Menai Strait. Gruffudd and Cadwgan regrouped on defensible Ynys Môn, where they planned to make retaliatory strikes from their island fortress.[2][18] Gruffudd hired a Norse fleet from a settlement in Ireland to patrol the Menai and prevent the Norman army from crossing; however the Normans were able to pay off the fleet to ferry them to Môn instead.[2][18] Betrayed, Gruffudd and Cadwgan were forced to flee to Ireland in a skiff.[2][18]

%252C_Anglesey.JPG.webp)

The Normans landed on Môn, and their furious 'victory celebrations' which followed were exceptionally violent with rape and carnage committed by Norman soldiers left unchecked.[2] The Earl of Shrewsbury had an elderly priest mutilated, and made the church of Llandyfrydog a kennel for his dogs.[2] During the 'celebrations', a Norse fleet led by Magnus Barefoot, King of Norway, appeared off the coast at Ynys Seiriol (Puffin Island), and in the battle that followed, known as the Battle of Anglesey Sound, Magnus shot dead the Earl of Shrewsbury with an arrow to the eye.[2] The Norse left as suddenly and as mysteriously as they had arrived, however leaving the Norman army weakened and demoralized.[2] The Norman army retired to England, leaving a Welshman, Owain ap Edwin, lord of Tegeingl, in command of a token force to control Ynys Môn and upper Gwynedd, and ultimately abandoning any colonization plans there.[2][25] Owain ap Edwin transferred his allegiance to Chester following the defeat of his ally Trahaearn ap Caradog in 1081, a move which earned him the epithet Bradwr, traitor, among the Welsh.[25] Nevertheless, Gruffudd did marry Owain ab Edwin's daughter Anghared.

Pura Wallia and Marchia Wallie

In late 1098 Gruffudd and Cadwgan landed in Wales and recovered Ynys Môn without much difficulty, with Hervé the Breton fleeing Bangor for safety in England. Over the course of the next three years Gruffudd recovered upper Gwynedd to the Conwy and defeating Hugh, Earl of Chester in border skirmishes.[2] In 1101, after Earl Hugh's death, Gruffudd and Cadwgan came to terms with England's new king, Henry I, who was consolidating his own authority and also eager to come to terms.

In the negotiations which followed Henry I recognized Gruffudd's ancestral claims of Môn, Arfon, Llŷn, Dunoding (Eifionydd and Ardudwy) and Arllechwedd (Môn, Caernarfonshire and northern Merionethshire), the lands of upper Gwynedd to the Conwy which were already firmly in Gruffudd's control.[2] Cadwgan regained Ceredigion, and his share of the family inheritance in Powys, from the new earl of Shrewsbury, Robert of Bellême.[2]

With the settlement reached between Henry I and Gruffudd ap Cynan, and other Welsh lords, the division of Wales between Pura Wallia, the two-thirds of Wales under Welsh control; and Marchia Wallie, the remaining one-third of Wales under Norman control, came into existence.[26] Author and historian John Davies notes that the border shifted on occasion, "in one direction and in the other", but remained more or less stable for almost the next two hundred years.[26]

Reconstruction of Gwynedd, 1101–1132

After generations of incessant warfare, Gruffudd began the reconstruction of Gwynedd, intent on bringing stability to his country.[18] According to Davies, Gruffudd sought to give his people the peace to "plant their crops in the full confidence that they would be able to harvest them".[18] Gruffudd consolidated princely authority in north Wales, and offered sanctuary to displaced Welsh from the Perfeddwlad, particularly from Rhos, at the time harassed by Richard, 2nd Earl of Chester.[27]

Alarmed by Gruffudd's growing influence and authority in north Wales, and on the pretext that Gruffudd sheltered rebels from Rhos against Chester, Henry I launched a campaign against Gwynedd and Powys in 1114, which included a vanguard commanded by King Alexander I of Scotland.[2][18] While Owain ap Cadwgan of Ceredigion sought refuge in Gwynedd's mountains, Maredudd ap Bleddyn of Powys made peace with the English king as the Norman army advanced.[2] There were no battles or skirmishes fought in the face of the vast host brought into Wales, rather Owain and Gruffudd entered into truce negotiations. Owain ap Cadwgan regained royal favor relatively easily. However Gruffudd was forced to render homage and fealty and pay a heavy fine, though he lost no land or prestige.[27]

The invasion left a lasting impact on Gruffudd, who by 1114 was in his 60s and had failing eyesight.[2] For the remainder of his life, while Gruffudd continued to rule in Gwynedd, his sons Cadwallon, Owain, and Cadwaladr, would lead Gwynedd's army after 1120.[2] Gruffudd's policy, which his sons would execute and later rulers of Gwynedd adopted, was to recover Gwynedd's primacy without blatantly antagonizing the English crown.[2][27]

In 1120 a minor border war between Lywarch ab Owain, lord of a commote in the Dyffryn Clwyd cantref, and Hywel ab Ithel, lord of Rhufoniog and Rhos (all three part of either Conwy county or Denbighshire) brought Powys and Chester into conflict in the Perfeddwlad.[27] Powys brought a force of 400 warriors to the aid of its ally Rhufoniog, while Chester sent Norman knights from Rhuddlan to the aid of Dyffryn Clwyd.[27] The bloody Battle of Maes Maen Cymro, fought a mile to the north-west of Ruthin, ended with Lywarch ab Owain slain and the defeat of Dyffryn Clwyd. However, it was a pyrrhic victory as the battle left Hywel ab Ithel mortally wounded.[27] The last of his line, when Hywel ab Ithel died six weeks later he left Rhufoniog and Rhos bereft.[27] Powys, however, was not strong enough to garrison Rhufoniog and Rhos, nor was Chester able to exert influence inland from its coastal holdings of Rhuddlan and Deganwy.[27] With Rhufoniog and Rhos abandoned, Gruffudd annexed the cantrefi back into Gwynedd, separated from Gwynedd since the initial Norman invasions.[27]

On the death of Einion ap Cadwgan, lord of Meirionydd, a quarrel engulfed his kinsmen on who should succeed him.[27] Meirionydd was then a vassal cantref of Powys, and the family there a cadet of the Mathrafal house of Powys.[27] Gruffudd gave licence to his sons Cadwallon and Owain to press the opportunity the dynastic strife in Meirionydd presented.[27] The brothers raided Meirionydd with the Lord of Powys as important there as he was in the Perfeddwlad.[27] However it would not be until 1136 that the cantref was firmly within Gwynedd's control.[27]

Perhaps because of their support of Earl Hugh of Chester, Gwynedd's rival, in 1124 Cadwallon slew the three rulers of Dyffryn Clwyd, his maternal uncles, bringing the cantref firmly under Gwynedd's vassalage that year.[27] And in 1125 Cadwallon slew the grandsons of Edwin ap Goronwy of Tegeingl, leaving Tegeingl bereft of lordship and annexed back into Gwynedd.[25]

However, in 1132 while on campaign in the commote of Nanheudwy, near Llangollen, 'victorious' Cadwallon was defeated in battle and slain by an army from Powys.[27] The defeat checked Gwynedd's expansion for a time, "much to the relief of the men of Powys", wrote historian Sir John Edward Lloyd (J.E Lloyd).[27]

The Great Revolt; 1136–1137

By 1136 an opportunity arose for the Welsh to recover lands lost to the Marcher lords after Stephen de Blois had displaced his cousin Empress Matilda from succeeding her father to the English throne the previous year, sparking the Anarchy in England.[28][29] The usurpation and conflict it caused eroded central authority in England.[28] The revolt began in south Wales, as Hywel ap Maredudd, lord of Brycheiniog (Brecknockshire), gathered his men and marched to the Gower, defeating the Norman and English colonists there.[28] Inspired by Hywel of Brycheiniog's success, Gruffydd ap Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, hastened to meet with Gruffudd ap Cynan of Gwynedd, his father-in-law, to enlist his aid in the revolt.[28] However, with Gruffydd ap Rhys' absence the Normans increased their incursions into Deheubarth, and Gwenllian, Princess of Deheubarth, gathered a host for the defense of her country.[30]

Gwenllian was the youngest daughter of Gruffydd ap Cynan of Gwynedd, and after she eloped with the Prince of Deheubarth she joined him resisting Norman occupation in south Wales.[30] Husband and wife led retaliatory strikes on Norman positions in Deheubarth, taking goods from the Norman, English, and Flemish colonists and redistributing them to Deheubarth's displaced Welsh, "as a pair of Robin Hoods of Wales", wrote historian Philip Warner.[30]

With her husband meeting with her father in Gwynedd, Gwenllian raised an army to counter Norman incursions ravaging Deheubarth.[30] Gwenllian met the Norman army, led by Maurice of London, near Kidwelly Castle, but her forces were routed.[28][30] Captured, the princess was beheaded by the Normans, the field where she lost her head later remembered as Maes Gwenllian, the 'Field of Gwenllian'.[28]

Though defeated, Gwenllian's 'patriotic revolt' inspired others in south Wales to rise.[28][30] The Welsh of Gwent, led by Iorwerth ab Owain (grandson of Caradog ap Gruffydd, Gwent's Welsh ruler displaced by the Norman invasions), ambushed and slew Richard de Clare, the grandson of the Norman lord Richard Fitz Gilbert.[28][30]

When word reached Gwynedd of Gwenllian's death and the revolt in Gwent, Gruffydd ap Cynan's sons Owain and Cadwaladr invaded Norman controlled Ceredigion, taking Llanfihangel, Aberystwyth, and Llanbadarn Fawr.[28][30] Liberating Llanbadarn, one local chronicler hailed Owain and Cadwaladr both as "bold lions, virtuous, fearless and wise, who guard the churches and their indwellers, defenders of the poor [who] overcome their enemies, affording a safest retreat to all those who seek their protection".[28] The brothers restored the Welsh monks of Llanbadarn, who had been displaced by monks from Gloucester brought there by the Normans who had controlled Ceredigion.[28]

By late September 1136 a vast Welsh host gathered in Ceredigion, which included the combined forces of Gwynedd, Deheubarth, and Powys; and met the Norman army at the Battle of Crug Mawr at Cardigan Castle.[28] The battle turned into a rout, and then into a resounding defeat of the Normans.[28]

Realizing how vulnerable they were to a resurgent Wales during the Great Revolt, the Marcher lords became estranged from Stephen de Blois due in large part to his lackluster response to the Welsh resurgence. These lords began shifting their allegiance back to the cause of Empress Matilda and the return of a strong royal government.[28][29]

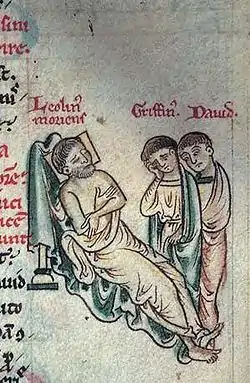

Gruffudd's death and legacy, 1137

Gruffudd ap Cynan, now elderly and blind, died in 1137.[31] With Gruffudd at his deathbed were his family, but also leading church figures, including the diocese bishop and trusted advisor David the Scot, the archdeacon of the diocese Simon of Clynnog, and the Prior of St Werburgh's in Chestor. Gruffudd bequeathed money to many notable churches throughout Gwynedd and in other lands, including the Danish foundation of Christ Church, Dublin, where he had worshipped as a boy growing up with his mother's people.[31] To his wife Princess Angharad,[32] who survived Gruffudd by twenty-five years, he left an estate and the profits from the port and ferry of Aber Menai, "the scene of many of his youthful adventures".[31] Prince Gruffudd was interred in a tomb erected in the presbytery of Bangor Cathedral, to the left of the high altar. "So rested at last a man whose life had been troubled and stormy in no common degree", wrote Lloyd. Meilyr Brydydd, Gruffudd's Pencerdd of Gwynedd, wrote:

The king of England came with his battalions-

Though he came, he returned not with cattle.

Gruffydd hid himself not, but with open force

Hotly did champion and protect his people.

Gruffudd died knowing that he left to his son Owain a more stable realm than had hitherto existed in Gwynedd for many generations, according to Lloyd.[31] No foreign army was able to cross the Conwy, nor raiders from across the hills, that might disturb Gwynedd's peace.[31] The stability provided by Prince Gruffudd allowed for a generation of Gwyneddwyr to settle and plan for the future without fear that their homes and harvests would "go to the flames" from invaders, according to Lloyd.[31] The Gwyneddwyr "planted orchards and laid out gardens, set up fences and dug out ditches; they ventured to build in stone and, in particular, raised stone churches in place of the old timer oratories", wrote Lloyd paraphrasing the Life of Gruffydd ap Cynan.[31][33] So many limewashed stone churches, the Eglwys Wen or White Churches, were built across Gwynedd that the principality "[became] bespangled with them as is the firmament with stars".[31] Gruffudd had stone churches built at his princely manors, and Lloyd suggests Gruffudd's example led to the rebuilding of churches with stone in Penmon, Aberdaron, and Towyn, all in the Norman fashion.[31] Additionally, Gruffudd funded the construction of Bangor Cathedral, dedicated to Saint Deiniol, under the episcopate of Gruffudd's advisor Bishop David the Scot. Gruffudd acquiesced to many of the Latin reforms brought to Wales in the wake of the Norman invaders, reforms such as a more structured episcopate within Gwynedd.[31]

Owain ap Gruffudd of Gwynedd

When their father Gruffudd ap Cynan died in 1137, the brothers Owain and Cadwaladr were on a second campaign in Ceredigion, and took the castles of Ystrad Meurig, Lampeter (Stephen's Castle), and Castell Hywel (usually known as Humphrey's Castle)[28]

Owain ap Gruffydd succeeded his father to the greater portion of Gwynedd in accordance to conventional Welsh law and custom, the Cyfraith Hywel, the Laws of Hywel.[34] Later historians refer to Owain ap Gruffydd as Owain Gwynedd to differentiate him from another Owain ap Gruffydd, the Mathrafal ruler of Powys, known as Owain Cyfeiliog.[35] Cadwaladr, Gruffudd's youngest son, inherited the commote of Aberffraw on Ynys Môn, and the recently conquered Meirionydd and Northern Ceredigion, that is Ceredigion between the rivers Aeron and Dyfi.[36][37]

By 1141 Cadwaladr and Madog ap Maredudd of Powys led a Welsh vanguard as an ally of the Earl of Chester as partisans for Empress Matilda in the Battle of Lincoln, and joined in the rout which made Stephen of England prisoner of the empress for a year.[38] Owain, however, did not participate in the battle, keeping the Gwyneddwyr army home.[38] Owain, of restrained and prudent temperament, may have judged that aiding Stephen de Blois' capture would lead to the restoration of Empress Matilda and a strong royal government in England; a government which would support Marcher lords, support absent since Stephen's usurpation.

Owain and Cadwaladr came to blows in 1143 when Cadwaladr was implicated in the murder of Prince Anarawd ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth, Owain's ally and intended son-in-law, on the eve of Anarawd's wedding to Owain's daughter.[39][40] Owain followed a diplomatic policy of binding other Welsh rulers to Gwynedd through dynastic marriages, and Cadwaladr's border dispute and murder of Anarawd threatened Owain's efforts and credibility.[30] As ruler of Gwynedd, Owain stripped Cadwaladr of his lands, with Owain's son Hywel dispatched to Ceredigion, where he burned Cadwaladr's castle at Aberystwyth.[39] Cadwaladr fled to Ireland and hired a Norse fleet from Dublin, bringing the fleet to Abermenai to compel Owain to reinstate him.[39] Taking advantage of the brotherly strife, and perhaps with the tacit understanding of Cadwaladr, the marcher lords mounted incursions into Wales.[40] Realizing the wider ramifications of the war before him, Owain and Cadwaladr came to terms and reconciled, with Cadwaladr restored to his lands.[39][40] Peace between the brothers held until 1147, when an unrecorded event occurred which led Owain's sons Hywel and Cynan to drive Cadwaladr out of Meirionydd and Ceredigion, with Cadwaladr retreating to Môn.[39] Again an accord was reached, with Cadwaladr retaining Aberffraw until a more serious breach occurred in 1153, when he was forced into exile in England, where his wife was the sister of Gilbert de Clare, 2nd Earl of Hertford and the niece of Ranulph de Gernon, 2nd Earl of Chester.[39][40]

In 1146 news reached Owain that his favoured eldest son and heir, Rhun, had died. Owain was overcome with grief, falling into a deep melancholy from which none could console him, until news reached him that Mold castle in Tegeingl (Flintshire) had fallen to Gwynedd, "[reminding Owain] that he had still a country for which to live", wrote historian Sir John Edward Lloyd.[41]

Between 1148 and 1151, Owain I of Gwynedd fought against Madog ap Maredudd of Powys, Owain's brother-in-law, and against the Earl of Chester for control of Iâl (Yale, near Wrexham), with Owain having secured Rhuddlan Castle and all of Tegeingl from Chester.[42] "By 1154 Owain had brought his men within sight of the red towers of the great city on the Dee", wrote Lloyd.[42]

Henry II's 1157 campaign

Having spent three years consolidating his authority in the vast Angevin Empire, Henry II of England resolved on a strategy against Owain I of Gwynedd by 1157. By now, Owain's enemies had joined Henry II's camp, enemies such as his wayward brother Cadwaladr and in particular Madog of Powys.[43] Henry II raised his feudal host and marched into Wales from Chester.[43] Owain positioned himself and his army at Dinas Basing (Basingwerk), barring the road to Rhuddlan, setting up a trap in which Henry II would send his army along the direct road along the coast, while he crossed through the woods to outflank Owain. The Prince of Gwynedd anticipated this, and dispatched his sons Dafydd and Cynan into the woods with an army, catching Henry II unaware.[43] In the melée which followed, known as the Battle of Ewloe, Henry II would have been slain had not Roger, Earl of Hertford rescued him.[43] Henry II retreated and made his way back to his main army, by now slowly advancing towards Rhuddlan.[43] Not wishing to engage the Norman army directly, Owain repositioned himself first at St. Asaph, then further west, clearing the road for Henry II to enter Rhuddlan "ingloriously".[43] Once in Rhuddlan, Henry II received word that his naval expedition had failed. Instead of meeting Henry II at Deganwy or Rhuddlan as the king had commanded, the English fleet had gone to plunder Môn.

The naval expedition was led by Henry II's maternal uncle (Empress Matilda's half-brother), Henry FitzRoy; and when they landed on Môn, Henry FitzRoy had the churches of Llanbedr Goch and Llanfair Mathafarn Eithaf torched.[43] During the night the men of Môn gathered together, and the next morning fought and defeated the Norman army, with Henry FitzRoy falling under a shower of lances.[43] The defeat of his navy and his own military difficulties had convinced Henry II that he had "gone as far as was practical that year" in his effort to subject Owain, and the king offered terms to the prince.[43] Owain I of Gwynedd, "ever prudent and sagacious", wrote Lloyd, recognized that he needed time to consolidate power further, and agreed to the terms. Owain was to render homage and fealty to the King, and resign Tegeingl and Rhuddlan to Chester, and restore Cadwaladr to his possessions in Gwynedd.[43]

The death of Madog ap Meredudd of Powys in 1160 opened an opportunity for Owain I of Gwynedd to press Gwynedd's influence further at the expense of Powys.[44] However, Owain continued to further Gwynedd's expansion without rousing the English crown and maintaining his 'prudent policy' of Quieta non movere (don't move settled things), according to Lloyd.[44] It was a policy of outward conciliation, while masking his own consolidation of authority.[44] To further demonstrate his goodwill, in 1160 Owain handed over to the English crown the fugitive Einion Clud.[44] By 1162 Owain was in possession of the Powys cantref of Cyfeiliog, and its castle of Tafolwern; and ravaged another Powys cantref of Arwystli, slaying its lord, Hywel ab Ieuaf, with both actions causing little apparent reaction from the Norman occupiers.[44] Owain's strategy was in sharp contrast to Rhys ap Gruffydd, prince of Deheubarth, who in 1162 rose in open revolt against the Normans in south Wales, drawing Henry II back to England from the continent.[44]

With Owain's growing influence throughout Wales as the premier Welsh ruler, Owain adopted the Latin title Princeps Wallensium, Prince of the Welsh, echoing historic Aberffraw claims as the primary royal family of Wales as senior line descendants of Rhodri the Great. The title was later given substance following the outcome of Great Revolt of 1166, wrote Professor John Davies.[45]

Great Revolt of 1166

In 1163 Henry II quarrelled with Thomas Becket, the Archbishop of Canterbury, causing growing divisions between the king's supporters and the archbishop's supporters. With discontent mounting in England, Owain I of Gwynedd joined with Rhys ap Gruffydd of Deheubarth in a second grand Welsh revolt against Henry II.[44][46] England's king, who only the previous year had pardoned Rhys ap Gruffydd for his 1162 revolt, assembled a vast host against the allied Welsh, with troops drawn from all over the Angevin empire assembling in Shrewsbury, and with the Norse of Dublin paid to harass the Welsh coast.[44] While his army gathered on the Welsh frontier, Henry II left for the continent to negotiate a truce with France and Flanders in order for them to not disturb his peace while campaigning in Wales.[47] However, when Henry II returned to England he found that the war had already begun, with Owain's son Dafydd raiding Angevin positions in Tegeingl, exposing the castles of Rhuddlan and Basingwerk to "serious dangers", wrote Lloyd.[47] Henry II rushed to north Wales for a few days to shore up defences there, before returning to his main army now gathering in Croesoswallt (Oswestry).[47]

The vast host gathered before the allied Welsh principalities represented the largest army yet assembled for their conquest, a circumstance which further drew the Welsh allies into a closer confederacy, wrote Lloyd.[47] With Owain I of Gwynedd the overall battle commander, and with his brother Cadwaladr as his second, Owain assembled the Welsh host at Corwen in the vale of Edeyrion where he could best resist Henry II's advance.[47] The Angevin army advanced from Oswestry into Wales crossing the mountains towards Mur Castell and found itself in the thick forest of the Ceiriog Valley where it was forced into a narrow thin line.[47] In the Battle of Crogen which followed; Owain I positioned a band of skirmishers in the thick woods overlooking the pass, where they harassed the exposed Angevin army from secured positions.[47] Henry II ordered the clearing of the woods on either side to widen the passage through the valley and to lessen the exposure of his army.[47] The road his army travelled later became known as the Ffordd y Saeson, the Englishmen's Road; it led through heath and bog towards the Dee.[47] In a dry summer the mountain moors may have been passable, however "on this occasion the skies put on their most wintry aspect; and the rain fell in torrents [...] flooding the mountain meadows" until the great Angevin encampment became a "morass", wrote Lloyd.[47]

Having suffered many setbacks, and in the face of "hurricane" force wind and rain, diminishing provisions and an exposed supply line stretching through hostile country subject to enemy raids, and with a demoralized army, Henry II was forced into a complete retreat without even a semblance of a victory.[47] In frustration, Henry II had twenty-two Welsh hostages mutilated; the sons of Owain' supporters and allies, including two of Owain's own sons.[47] In addition to his failed campaign in Wales, Henry's mercenary Norse navy, which he had hired to harass the Welsh coast, turned out to be too small to be useful, and was disbanded without engagement.[47] Henry II's Welsh campaign was a complete failure, with the king abandoning all plans for the conquest of Wales, returning to his court in Anjou and not returning to England for another four years.[47] Lloyd wrote;

It is true that [Henry II] did not cross swords with [Owain I], but the elements had done their work for [the Welsh]; the stars in their courses had fought against the pride of England and humbled it to the very dust. To conquer a land which was defended, not merely by the arms of its valiant and audacious sons, but also by tangled woods and impassable bogs, by piercing winds and pitiless storms of rain, seemed a hopeless task, and Henry resolved to no longer attempt it.[47]

Owain expanded his international diplomatic offensive against Henry II by sending an embassy to Louis VII of France in 1168, led by Arthur of Bardsey, Bishop of Bangor (1166–1177), who was charged with negotiating a joint alliance against Henry II.[46] With Henry II distracted by his widening quarrel with Thomas Becket, Owain's army recovered Tegeingl for Gwynedd by 1169.[46]

The following year, Prince Owain ap Gruffydd died and was interred in Bangor Cathedrial, near his father Gruffudd ap Cynan.

The Poet-Prince and the Gwynedd interregnum; 1170–1200

As the eldest surviving son and elding, Hywel succeeded his father in 1170 as Prince of Gwynedd in accordance with Welsh law and custom.[34][48][49] However, the new prince was immediately confronted by a coup d'état instigated by his step-mother Cristin, Princess Dowager of Gwynedd, possibly leading an anti-Irish faction at court.[50] The dowager princess plotted to have her eldest son by Owain, Dafydd, usurp the Crown and Throne of Gwynedd from Hywel; and with Gwynedd divided between Dafydd and her other sons Rhodri and Cynan.[48] The speed with which Cristin and her sons acted suggest that the conspiracy may have had roots before Owain's death. Additionally, the complete surprise of the elder sons of Owain suggests that the scheme had been a well kept secret.

Within months of his succession Hywel was forced to flee to Ireland, returning later that year with a Hiberno-Norse army and landing on Môn, where he may have had his younger half brother Maelgwn's support.[51][52] Dafydd himself landed his army on the island and caught Hywel off guard at Pentraeth, defeating his army and killing Hywel.[51][52] Following Hywel's death and the defeat of the legitimist army, the surviving sons of Owain came to terms with Dafydd. Iorwerth- who was next in line of succession after his slain brother Hywel- was apportioned the commotes of Arfon and Arllechwedd, with his seat at Dolwyddelan, with Maelgwn retaining Ynys Môn, and with Cynan receiving Meirionydd.[48][53][54][55] However, by 1174 Iorwerth and Cynan were both dead and Maelgwn and Rhodri were imprisoned by Dafydd, who was now master over the whole of Gwynedd.[48][56]

During the upheavals of 1173–74 Dafydd had remained loyal to Henry II, and as if in reward for his loyalty, but also in recognition of Dafydd's apparent supremacy in north Wales, Dafydd married the king's half-sister Emma of Anjou.[48][57] Henry II did not approve of the match, but needed a Welsh ally to distract from the resurgent Welsh of South Wales under The Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth and rebellious marcher lords.[48] However, Dafydd's ascendency was short-lived as Rhodri had escaped his imprisonment and took Arfon, Llŷn, Ynys Môn, and Arllechwedd, with Meirionydd, Ardydwy, and Eifionydd returned to Gruffydd and Meredudd ap Cynan.[48][58] Though Henry II continued to recognize his brother-in-law Dafydd as Prince of Gwynedd he did not send aid to him, and Dafydd effectively had to content himself with the rule of lower Gwynedd, the Perfeddwlad, establishing court at Rhuddlan Castle.[48] The following year Dafydd joined with other Welsh rulers in swearing fealty to Henry II at Oxford.[48]

Rise of Llywelyn the Great

By 1187, on reaching his majority in Welsh law at age 14, Llywelyn ab Iorwerth began asserting his senior claim as Prince of Gwynedd over those of his paternal uncles Dafydd and Rhodri, harassing their positions with the aid of Gruffydd Maelor, lord of Powys Fadog and Llywelyn's maternal uncle; as attested to by Gerald of Wales who was traveling through north Wales in 1188 recruiting soldiers for the Third Crusade.[34][60][61] Llywelyn ab Iorwerth was raised in exile with his mother's Mathrafal family in Powys, primarily in the court of Powys Fadog in Maelor.[61][62][63][64]

While Dafydd maintained his alliance with the English Crown, Rhodri allied with The Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, who was now the pre-eminent prince in Wales and now styled himself Princeps Wallensium, or Prince of the Welsh, in the tradition of Owain Gwynedd.[48][65][66] Rhodri was beset by his nephews Gruffudd and Meredudd ap Cynan, the two brothers ejecting Rhodri from Môn in 1190. That same year, Rhodri allied with Ragnvald Godredsson, King of the Isles, solidifying their alliance with a diplomatic marriage.[48] By summer of 1193 Rhodri and a contingent of allied Manx forces recovered Môn, a period known as the 'Gaelic Summer' "so called, no doubt, because of the influx of Gaelic-speaking allies from Mann into Gwynedd", argued J.E. Lloyd.[48]

In 1194 the brothers Gruffudd and Meredudd ap Cynan recovered Môn ejecting Rhodri for the second time. Then they allied with their paternal cousin Llywelyn ab Iorwerth in his bid to reclaim his inheritance.[48] Llywelyn and his allied cousins defeated their uncle Dafydd, the usurper Prince of Gwynedd, at the Battle of Aberconwy and taking lower Gwynedd.[48][67] The allies continued to win victories at Porthaethwy on the Menai and at Coedeneu on Môn.[48] By 1195 Llywelyn controlled all of lower Gwynedd (the Perfeddwlad), with his cousin Gruffudd ap Cynan retaining Môn, and the commotes of Arfon, Arllechwedd, and Llŷn, and with Maredudd ap Cynan given Meirionydd and the lands just north as his share.[48]

Llywelyn pursued a policy of consolidation for the next five years, first with his capture of Dafydd in 1197, and then in 1198 when he sent a vanguard to the assistance of his then ally Gwenwynwyn of Powys in his campaign to take Painscastle; but it was Llywelyn's capture of Mold Castle in 1199 which was his most significant achievement at the close of the 12th century, argued Lloyd.[48][68]

Llywelyn, John, and the Magna Carta; 1200–1216

In 1200 Llywelyn ab Iorwerth recovered upper Gwynedd on the death of his cousin Gruffudd ap Cynan, with Gruffudd's son Hywel swearing fealty to Llywelyn as his lord and receiving Meirionydd as his portion by 1202.[69][70] As Llywellyn ruled over all of Gwynedd by the end of 1200, the English crown was compelled to endorse all of Llywellyn's holdings that year.[71] However, England's endorsement was part of a larger strategy of reducing the influence of Gwenwynwyn ab Owain of upper Powys, who had filled the power vacuum left with the death of the Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, in 1197; and with Gwynedd divided over the past generation.[71][72] John of England had given William de Breos licence in 1200 to "seize as much as he could" from the native Welsh, particularly from Powys.[73] De Breos held lordship over Abergavenny, Brecon, Builth, and Radnor, and was one of the most powerful Marcher barons.[73] However, de Breos was out of favor with King John by 1208, and with de Breos and the king quarreling Llywelyn took the opportunity to seize both southern Powys and northern Ceredigion.[73][74] Llywellyn's expansion was a "bold demonstration of the determination of the ruler of Gwynedd to be master of Pura Wallia", and echoed historic Aberffraw claims as primary rulers of Wales since Rhodri the Great in the 10th century, argued John Davies.[73][75][76]

In his expansion, the Welsh prince was careful not to antagonise the English king, his father-in-law.[71] Llywelyn had married Joan, King John's illegitimate daughter, in 1204.[77] In 1209 Prince Llywelyn joined King John on his campaign in Scotland, a "repayment of an old debt", argued Davies, for Alexander I, King of Scots, had joined Henry I on his campaign against the Welsh in 1114.[77] However, by 1211 King John perceived the growing influence of Llywelyn as a threat to English authority in Wales, and invaded Gwynedd reaching the banks of the Menai.[73] Llywelyn was forced to cede the Perfeddwlad and recognize John as his heir if Llywelyn's marriage with Joan did not produce any legitimate successors.[73] Welsh law recognized children born out of wedlock as equal to those in born in wedlock, and according to Welsh custom Llywelyn's eldest son Gruffydd, by his longtime companion Tangwystl, may have expected to be his father's heir.[34][78]

Many of Llywelyn's Welsh allies had abandoned him during England's invasion of Gwynedd, preferring an overlord far away rather than one nearby.[79] These Welsh lords expected an unobtrusive English crown, however King John had castles built in Ystwyth in Ceredigion, and John's direct interference in Powys and the Perfeddwlad caused many of these Welsh lords to rethink their position.[79][80] John's policy in Wales demonstrated his resolve to subject the Welsh, argued Professor John Davies.[79]

Llywelyn capitalized on Welsh resentment against King John, and led a church sanctioned revolt against him.[79] As King John was an excommunicate in the Catholic Church, Innocent III gave his blessing to Llywelyn's revolt, possibly even lifting Pura Wallia from the interdict.[79] Early in 1212 Llywelyn had regained the Perfeddwlad, striking at Marcher positions in Wales, and burned the castle at Ystwyth, with the Cronica de Wallia (Chronicle of Wales) recording that the Welsh lords chose Llywelyn as their 'one leader'.[79][81] Llywelyn's revolt caused John to postpone his invasion of France, with Philip II of France so moved as to contact Prince Llywelyn and propose that they ally against the English king[82] King John ordered the execution by hanging of his Welsh hostages, the sons of many of Llywelyn's supporters[73]

John's relationship with his nobles deteriorated further following the king's disastrous campaign to reconquer Normandy and Anjou from France in 1213, with the nobles eager to ally with Prince Llywelyn.[79] Llywelyn's aid to England's nobles, in particular Llywelyn's seizure of Shrewsbury in May 1215, was one of the major factors which persuaded John to seal the Magna Carta in June 1215.[79] Llywelyn wrestled significant concessions from the English Crown in the Magna Carta.[79] Land seized unjustly during the conflict would be returned to the other, and the primacy of Welsh law to apply in Pura Wallia (two-thirds of the surface area of Wales)- particularly with succession to land and title- was reaffirmed, and with Marcher Law to determine rights to land held in the March.[79] The use of the term 'Marcher Law' in the Magna Carta was the first clear reference to the hybrid of Welsh and English law used in the march.[79] The sealing of the Magna Carta did not end the conflict between John and England's nobles sparking First Barons' War, and Llywelyn continued to press his advantages in south and mid Wales by taking many English castles between 1215 and 1216, including the important Carmarthen and Cardigan castles among them.[79]

Aberdyfi, Worcester, and Strata Florida; 1216–1240

Llywelyn's influence was felt all across Wales as he aimed to give substance to the long-standing Aberffraw claim as the primary rulers of Wales.[83] The prince used the structures of feudalism to strengthen his position, and between 1213 and 1215 received oaths of allegiance and homage from the rulers of Powys Fadog, Powys Wenwynwyn, Maelgwn of Deheubarth, and the Welsh in Gwent and the uplands of Glamorgan, and the Welsh barons in the region between the Wye and Severn.[83] Additionally, Llywelyn threatened the long occupied Marcher positions in Haverfordwest in Pembroke, and the Braose controlled Swansea and Brecon.[79] In 1216 Llywelyn convened the Council of Aberdyfi with all the Welsh lords in Pura Wallia in attendance.[83] The choice of Aberdyfi as the place to hold the assembly was significant as the location was where Llywelyn's direct ancestor, Maelgwen the Great, had been recognized as overlord and king of Wales in the 6th century.[83][84] At Aberdyfi, Llywelyn held court and presided over the division of Deheubarth between the descendants of Rhys ap Gruffydd,[85] with the rulers of Pura Wallia reaffirming their homage and oath of alliagence.[83] Effectively all other rulers of Pura Wallia were mediatized and subsumed into the de facto Principality of Wales, according to Dr. John Davies.[83] Author and historian Beverly Smith wrote of the Council of Aberdyfi, "Henceforth, the leader would be lord, and the allies would be subjects".[83] However, when hostilities broke out between King John and his barons again later that year, Gwenwynwyn of Powys Wenwynwyn broke his oath of allegiance to Llywelyn and sided with the king. Llywelyn reacted by seizing Powys Wenwynwyn "in accordance with the rights of a feudal overlord", according to Davies.[83]

in 1216, King John died leaving his nine-year-old son Henry III as king of England; and the coalition against royal authority in England collapsed.[86][87] The election Honorius III as pope, an ally of the House of Plantagenet, transferred the full weight of ecclesiastical Roman power away from the baronial party in favor of the royalists, with the pope now excommunicating all the barons who had previously sided against King John.[87] Papal legat Guala Bicchieri pronounced the whole of Wales under interdict for Llywelyn's support of King Louis VIII of France, and the Welsh prince was deprived of valuable allies in the upcoming year.[87][88][89] "Each one", wrote Lloyd, "an ally lost to Llywelyn in his contest with the [English] Crown".[87] Complicating matters was the successful recasting of the struggle from one of a civil war between the English King and his barons to one between the English against "foreign" French rule.[87]

Henry III's regents, including William Marshal, were anxious to reach a settlement with Llywelyn and endorsed much of Llywelyn's achievements after lengthy negotiations with the 1218 Treaty of Worcester.[86][87] However William Marshal was also the Marcher Earl of Pembroke (by marriage to the de Clare heiress Isabel), and insisted on certain restrictions to curb Llywelyn's expansion.[86][87] Llywelyn was not to retain the direct vassalage of the Dinefwr lords of Ceredigion and of Ystrad Tywi (Cantref Mawr and Cantref Bychen), or of Powys, and Llywelyn could garrison the castles of Carmarthen and Cardigan only until Henry III came of age.[86][90] Nor was Llywelyn able to restore his ally Morgan ap Hywel to his ancestral seat of Caerleon in Gwent. However, because Powys' new lord Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn was himself in his minority, Llywelyn would be able to govern Powys and Maeliennydd until Gruffydd ap Gwenwynwyn came of age.[86]

Within five years English officials sought to reverse Welsh gains of the Treaty of Worcester, and in 1223 Earl William Marshal of Pembroke, now the rector of England, took the castles of Carmarthen and Cardigan.[91] That same year Hubert de Burgh, justicar of England, ordered a more defensible castle to be built in Montgomery.[91] However, as de Burgh sought to expand his influence in Powys he was met by Llywelyn and utterly trounced in battle at Ceri in 1228. De Burgh's defeat did not stop him from winning control of other Marcher lordships, further provoking Llywelyn.[91] The Welsh prince led his armies into regions "where a Welsh army had not been seen for a century or more", wrote Davies.[91] Llywelyn burned Brecon, marched through Glamorgan and destroyed Neath. Alarmed, Henry III appealed to Hiberno-Norman knights in Norman colonized Ireland and offered them any lands in Wales they might win from Llywelyn.[91] However, Henry's efforts proved too ineffective against Llywelyn, and by 1232 the Peace of the Middle was signed restoring the Welsh prince to the position he enjoyed in 1216.[91] With the Middle Peace, Llywelyn adopted a new title Prince of Aberffraw and Lord of Snowdonia, emphasizing his preeminent position as overlord of all Wales.[91][92][93]

The question of succession came to occupy much of Llywelyn's domestic and foreign policies following the 1216 Council of Aberdyfi.[91] Llywelyn had an elder son, Gruffydd the Red, who according to Welsh custom was considered by many as the heir apparent.[94][95][96] However, the now defunct 1211 treaty,[97] in which the English crown would only recognize legitimate issue born of Llywelyn and Joan as heirs of Gwynedd, demonstrated to Llywelyn the value the wider Western polity placed on legitimate birth. Additionally, Llywelyn's own successes, chiefly overcoming his usurper uncle, could be viewed as a triumph for legitimacy, argued Lloyd.[94] Considering this, Llywelyn went to great lengths to secure the succession of his second but legitimate son Dafydd, born to Joan.[94] In amending Welsh custom, Llywelyn had an example from which to draw from. The Lord Rhys, Prince of Deheubarth, had reached a similar conclusion about legitamcy in the latter part of the 12th century, and had set aside his eldest illegitimate son Maelgwn in favor of his legitimate second son Gruffydd. However, Rhys' untimely death in 1197 and the two Dinefwr brother's rivalry over the succession plunged Deheubarth into a disastrous civil war not settled until its full division in 1216.

Llywelyn sought to avoid the pitfalls the Dinefwr example revealed and curried favor with his brother-in-law Henry III of England.[91] Despite the occasional conflict between the Welsh prince and the English king, their personal relationship as brothers-in-law was not one of constant discord, and for the greater period between 1218 and 1240 there was a sense of amenity between the two.[91] Henry III fully endorsed Dafydd as Llywelyn's heir, and in 1226 Henry III had successfully petitioned the Papacy to free his sister Joan from any stigma of illegitimacy.[91] In 1229, Dafydd traveled to London to do homage for the lands he would inherit, and Llywelyn arranged for the advantageous marriage between Dafydd and Isabella de Braose, daughter and co-heiress of Llywelyn's powerful ally the Marcher lord William de Breos.[98][99][100][101]

Shortly before 1238 Llywelyn, now aged 65, suffered a slight paralytic stroke.[102] In an effort to assure a smooth transition from his rule to that of his son's rule, the prince assembled his vassals and bishops at the Assembly of Strata Florida in Ceredigion. The choice of Strata Florida as the venue for the ceremony was significant as a gauge of how complete the Aberffraw victory was in their claim as the primary princes of Wales and heirs of Rhodri the Great. The Cistercian abbey, founded in 1164, was under the patronage of the Dinefwr family, dynastically junior rivals (but also, at times, allies of necessity) of the Aberffraw family.[103] In a ceremony rich in feudal pageantry and with an act of homage reminiscent of Capetian France, the leading magnates of Wales swore fealty and allegiance to Dafydd as their future feudal overlord, suzerain, and prince.[91][104]

Llywelyn's death and legacy

In weakened health, on 10 April 1240, Llywelyn abdicated in favor of his son Dafydd, had taken the monastic habit and entered into the Cistercian Abbey at Aberconwy. The next day Llywelyn died, with a Cistercian annalist writing "Thus died that great Achillies the Second, the Lord Llywelyn [...] whose deeds I am unworthy to recount. For with lance and shield did he tame his foes; he kept the peace for the men of religion; to the needy he gave food and raiment. With a warlike chain he extended his boundaries; he showed justice to all [...] and by the meet bonds of fear and love bound all men to him".[102] Lloyd wrote that of all the Welshmen who fought against Anglo-Norman influence in Wales, Llywelyn's "place will always be high, if not indeed the highest of all, for no man ever made better or more judicious use of native force of the Welsh people for the adequate national ends; his patriotic statesmanship will always entitle him to wear the proud style of Llywelyn the Great".[102]

Though the prince was often engaged in conflicts, his battles were largely in Marcher controlled territories and directed against Marcher positions. For the greater period of Llewellyn's reign, the lands under his rule were at peace, a peace for which his vassals sought his protection. "Hardly a ripple disturbed the face of the waters [and] Welsh society followed the lines of its natural development", according to J.E. Lloyd.[105]

The prince was an experienced and astute politician, according to Professor John Davies, whose legacy for Wales in law and government included the continued refinement and sophistication of his government's administration and with the legal system within the principality.[106] Though the principality's archive has disappeared, what remains of Llywelyn's correspondence with English and French counterparts reveal that the prince's chancery produced documents of high quality in both Latin and in French, the lingua franca of the era, with the volume of documents increasing substantially after 1200.[106] T. Jones Price notes that the Welsh principality was developing the prerequisites characteristic of a cohesive state,[106] along similar lines to continental kingdoms such as France, Navarre, and León. As in England and elsewhere, the prince issued charters, diplomas, grants, and summons, each affixed with the prince's great seal.[106] Political offices emerged from the prince's household, as in other realms, which formed the nucleus of the Welsh government.[106] The distain was a kind of prime minister, the chamberlain as the treasurer, and with clerks as chancellors.[106] Localized communities became increasingly dependent on the prince's administration, with the prince's appointed judges adjudicating and passing sentences at the commote court.[106] Under the prince's patronage, Welsh law was further codified by the Welsh jurist Iorwerth ap Madog and published sometime around 1240, and known as the Book of Iorwerth, or the Iorwerth Redaction.[107]

As with much of Europe, Wales remained predominantly rural at the turn of the 13th century, but Llywelyn encouraged the growth of quasi-urban settlements within the Welsh principality which served as centres of trade and commerce.[106] Money grew in circulation, with freemen and nobles paying their taxes in the form of money rather than in produce, at least in the more fertile of the principality's commotes.[106]

Llywelyn was no less influential in matters of the Welsh Church as he was in war and politics, and demonstrated that he was open to religious reforms and "accessible to new impulses and ideas", according to Lloyd.[105] Llywelyn lent his support to Gerald of Wales' efforts in elevating St. David's into a metropolitan archbishopric with jurisdiction over the whole of Wales, though he would not directly benefit from having the Bangor diocese subject to it.[105] Llywelyn secured the election of Welshmen to vacant Welsh dioceses, largely filled with Anglo-Normans following the Norman invasion of Wales.[105][108] However, by 1216 Llywelyn's influence in Wales was so wide that he encouraged the election of Iorwerth, abbot of Talley (Abaty Talyllychau), as Bishop of St David's in 1214,[105] the first Welshman elected and consecrated there in 100 years. In 1215, Llywelyn had encouraged the election of Cadwgan of Llandyfai, Cistercian abbot of Whitland Abbey (Abaty Hendy-gwyn ar Daf) and son of a famous Welsh priest, as Bishop of Bangor.[105] Llywelyn befriended the monks of Ynys Lannog (Prestholm), who were not members of any religious order but "anchorites of the old Welsh pattern," according to Lloyd.[105] However it was the Cistercian order with its ascetic values approximating the Rule of Saint David of which Llywelyn became most fond of.[105] The prince donated great tracts of land to the Cistercians, particularly in Cymer and Aberconwy.[105] Additionally, Llywelyn patronized the Knights Hospitaller and donated lands to them at Dôl Gynwal, subsequently known as Ysbyty Ifan (Hospital of John), on the banks of the Conwy. Additionally, Llywelyn warmly welcomed the new order of Franciscans, who had come to Britain and Ireland only after 1200, to Wales.[105]

Dafydd II, the Buckler of Wales; 1240–1246

Dafydd II succeeded his father with ease as he had the support of his father's chief advisors and the principality's leading magnates, including support from Ednyfed Fychan, Bishop Hywel of St. Asaph, and Einion Fychan.[98][109] Dafydd's half-brother Gruffydd was closely guarded, and his supporters were all but silenced with the exception of his wife Senena and of Bishop Richard of Bangor who spoke publicly on Gruffydd's behalf.[109] Shortly after his ascension, Dafydd attended the royal court in Gloucester where he performed homage for his inheritance and wearing Gwynedd's talaith, or coronet, the special symbol of his rank, according to Lloyd.[109]

However, though Dafydd's rule began auspiciously and in "peace and security", there were plots devised to reduce his and his house's influence, both in Gwynedd and over the whole of Wales.[98][109] Claimants to the lands Llywelyn incorporated into his expanded principality petitioned the English king for redress.[109] Diplomatic and legal battles ensued throughout 1241 as Dafydd agreed to put the matter of the disputed lands to a committee of arbitrators, partly English and partly Welsh, and headed by the pope's legate Otto.[109] Collectively the arbitrators were deputized to adjudicate on the legal possessors of the lands in question.[109] However, Dafydd subsequently failed to appear at three of the designated hearings, which delayed the proceedings.[109] Patience exhausted, Henry III gathered a host and prepared to invade Wales in July and August in direct violation to the church sanctioned arbitration agreement.[109] In the face of the military intervention before him, Prince Dafydd was almost bereft of any allies.[109] Gruffydd ap Madog of upper Powys (son of Madog, who had been an ardent supporter and vassal of Dafydd's father Llywelyn), Maredudd ap Rhotpert, and Maelgwn Fychan all deserted him.[109] Additionally, Henry III granted the petition of Senena, wife of Gruffydd ap Llywelyn, to force Dafydd to release her husband from confinement and to be restored to a portion of Gwynedd as was due his inheritance. With the summer of 1241 remarkably dry, Dafydd found himself abandoned of yet another ally which, as Lloyd wrote, "rarely failed a Welsh chief in his hour of need, the Welsh climate."[109] Marshes dried up, rivers became fordable while lakes shrank into shallow pools, and the natural obstacles which usually made campaigning in Wales most difficult all but disappeared. Within four weeks Henry was at Rhuddlan and Dafydd agreed to submit before him.[109]

Henry would allow his nephew to retain the title and rank of prince, but otherwise the treaty terms were harsh.[109] Gruffydd and his son Owain would be turned over to the king with the plan to have Gruffydd established as an independent ruler somewhere in North Wales as a counterweight to Dafydd.[109] All of the conquests of Llywelyn, including of Meirionydd, Maelienydd, Mold, and of lower Powys, were returned to other claimants; and all homages of Welsh vassals were to be transferred back to the English crown.[98][109] Dafydd was to pay for the expenses of the war (eventually having to cede Tegeingl and Deganwy, both in lower Gwynedd, to England to cover war expenses) and lost his inheritance of Ellesmere in England, his late mother's marriage dowry.[109] Henry III repossessed Cardigan and Carmarthen in Deheubarth,[98] while John of Monmouth occupied Builth, Dafydd's wife's dowry. Dafydd's ally Maredudd ap Rhys Gryg was forced out of Kidwelly and Widigada.[109] Most importantly, however, Henry III insisted that Gwynedd would pass to the English crown if Dafydd II were to die without an heir.[98]

Though Henry III did initially intend to install Gruffydd ‘somewhere’ in North Wales as a counterweight to Dafydd, in the end Henry "spared [Dafydd] the last humiliation" of dividing Gwynedd to share between the brothers, and Gruffydd and his son Owain were installed instead in the Tower of London, "trading a Welsh prison for an English one", wrote Lloyd.[109] Gruffydd remained popular amongst some traditionalist Welsh, and a ‘legitimist’ faction had emerged to promote his rights above those of Dafydd.[109] Henry III thought to keep Gruffydd as prisoner and as leverage against Dafydd for ‘good behavior’.[109] If Dafydd were to rebel then Henry III would release Gruffydd into Gwynedd to attract his supporters and causing a dynastic civil war in Gwynedd.[109] Dafydd's policy therefore was one of prudence and self-restraint as he maintained the status quo.[109] Then, on St. David's Day 1244, in a daring escape attempt Gruffydd fell to his death when his improvised rope of torn bed sheets and table linens gave way as he tried to propel from the White Tower.[109]

Gruffydd's death released Dafydd from the threat of rival and within a few weeks the flag of revolt was flown across Wales.[109] Dafydd emerged as the popular leader as he publicly lamented the indignant treatment of his brother, and with Gruffydd's second eldest son Llywelyn beside and supporting his uncle.[98][110] The lesser Welsh lords again swore fealty to Dafydd as their leige lord, including the Dinefwr lords in Deheubarth.[98][109] However, the two lords of upper and lower Powys, and Morgan of Gwenllwg, remained aloof to the revolt.[109] The summer of 1244 emerged as one of unrest and strife as Dafydd stirred up his supporters the length and breadth of Wales. Nightly Welsh soldiers raided English positions, Diserth was under siege, and Powys’ province of Cyfeiliog was raided as punishment for Gwenwynwyn's support for the English king.[109] In addition to military strikes on English positions, Dafydd opened a diplomatic offensive against the English crown by appealing directly to Pope Innocent IV, a "bold and original strategy", according to Lloyd.[109] In his plea to the pope, Dafydd offered to hold the Welsh principality as a Papal vassal, noting that Rome had acknowledged his rights as heir. Dafydd's plan had precedents, according to Davies, as "by 1244 about a dozen European rulers have become direct vassals of the Papacy, and the Pope had proved his ability to make and unmake kingdoms."[98] While awaiting the Pope's reply, Dafydd had begun to style himself formally as Prince of Wales, denoting not only the popular monarchy over the Welsh which his earlier forefathers had taken with the title Prince of the Welsh and the title Prince of Aberffraw and Lord of Snowdon, but over a clearly defined territorial principality incorporating the whole of Wales as distinct from England.[98]

In writing to the Pope, Dafydd's intention was to free himself from the overlordship of the king of England, and the essence of his offer was an attempt to assert the independence of his principality. It was no longer the principality of Gwynedd for, while awaiting the Pope's reply, Dafydd had begun to style himself Prince of Wales. The title was more challenging, in so far as it was more territorial, then the title Prince of the Welsh which had sometimes been employed by his predecessors.

— John Davies, History of Wales, pg 144.[98]

A sympathetic Innocent IV appointed the abbots of Cymer and Aberconwy as papal commissioners charged with summoning Henry III to answer charges of wantonly casting aside arbitration in his 1241 campaign in Wales in favor of war.[109] Henry III ignored the summons and sent his own envoy to Rome with the royal version of events, which sent word by 1245 transferring jurisdiction from the Welsh abbots to the Archbishop of Canterbury, "revealing not obscurely the influence of the weightier purse", according to Lloyd.[109]

Initially Henry took little interest in Dafydd's revolt as he was distracted by possible Scottish plans at an invasion in northern England, and deputized the marcher lords the earls of Gloucester and Hereford, and the two wardens of the March, John of Monmouth and John Lestrange, and later a contingent of knights under the command of Herbert fitz Mathew, with all five proving ineffective against the Welsh prince.[109] Frustrated, Henry III released Owain the Red into Gwynedd, hoping that the affection Gruffydd had held among some Welsh would transfer to Owain and divide the Welsh in their loyalties.[109] However, the Welsh fully backed Dafydd who continued to win victories in the spring of 1245. Herbert fitz Mathew was killed by a force of Welsh of Rhwng Nedd ac Afan, and though 300 Welsh soldiers were killed in an ambush near Montgomery, Dafydd took Mold castle on 28 March.[109]

Henry III began to realize that Dafydd was a far more formidable adversary then he had countenanced in 1241, and assembled an army in Chester by 13 August 1245.[109] From Chester Henry's army pushed along the coast towards Degannwy, where he pitched camp on the 26th.[109] Here, Henry remained for two months as he built up the fortress while exposing his army to the persistent attacks and harassments by the Welsh from across the Conwy River. Henry's army became demoralized, and, in one letter preserved by Matthew Paris, a soldier wrote,

We dwell here in watchings and fastings, in prayer, in cold and nakedness. In watchings, for fear of the Welsh, with their sudden raids upon us by night. In fastings, for lack victuals, since the halfpenny loaf cannot be got for less than a fivepence. In prayer, that we may quickly return safe and sound to our homes. In cold and nakedness, for we live in houses of linen and have no winter clothes.

Henry's army, deep behind enemy lines, was ill provisioned by sea with the road from Chester routinely raided by Welsh skirmishers. As the summer turned to fall, the war raged on ruthlessly.[109] English forces sacked the Cistercian Monastery of Aberconwy (now Conwy Castle), almost directly opposite the Conwy River from Degannwy, and executed Welsh hostages, including the young son of Ednyfed Fychan.[109] In retaliation, the Welsh hung and beheaded their captives.[109] Irish mercenaries in Henry's service raided Ynys Mon destroying the harvest.[109] By late October Henry retreated from Degannwy and returned to England, his campaign of 1245 a failure.[109] But if Henry's campaign was a defeat, Dafydd's wasn't a clear victory either, as Henry left behind a new castle at Degannwy which was- for Dafydd- a ‘throne in the eye’ and a clear sign by Henry for the speedy renewal of the war at another time.[109]

Before the war could be renewed, Dafydd II died at his court in Aber, 25 February 1246, survived by his wife Princess Isabella, but no heirs to transmit his claim to.[109] The question of whether or not Prince Dafydd II could have maintained his position indefinitely against Henry III will always be uncertain, according to Lloyd, but what can be said of the prince was that during his brief rule he "showed himself, in courage, prudence, and leadership, no unworthy son of the great Llywelyn."[109] The chronicler mourned the loss of the buckler of Wales;[109] and Dafydd Benfras set his harp to plaintive strains in honor of the fallen chief;

He was a man who sowed the seed of joy for his people,

Of the right lineage of kings,.

So lordly his gifts, ‘twas strange

He gave not the moon in heaven!

Ashen of hue this day is the hand of bounty

The hand that last year kept the pass of Aberconwy.

Dafydd's death left the native Welsh of all regions bereft of national leadership able to defend against the encroachment of their customs and way of life.[109] Of the next ten-year period J.E. Lloyd wrote "[I]t was a time during which the sense of national solidarity was for the moment lost."[109] Llywelyn the Great and Dafydd's principality was all but dismembered, and Henry III was now firmly in possession of lower Gwynedd, the Perfeddwlad, while upper Gwynedd was on the verge of a dynastic civil war between the elder sons of Gruffydd the Red; Owain and Llywelyn ap Gruffudd.[109][111]

Brother versus brother; 1246–1255