History of Sicily

The history of Sicily has been influenced by numerous ethnic groups. It has seen Sicily sometimes controlled by external powers – Phoenician and Carthaginian, Greek, Roman, Vandal and Ostrogoth, Byzantine Greek, Islamic, Norman, Aragonese and Spanish – but also experiencing important periods of independence, as under the indigenous Sicanians, Elymians and Sicels, and later as the County of Sicily and Kingdom of Sicily. The Kingdom was founded in 1130 by Roger II, belonging to the Siculo-Norman family of Hauteville. During this period, Sicily was prosperous and politically powerful, becoming one of the wealthiest states in all of Europe.[1] As a result of the dynastic succession, then, the Kingdom passed into the hands of the Hohenstaufen. At the end of the 13th century, with the War of the Sicilian Vespers between the crowns of Anjou and Aragon, the island passed to the latter. In the following centuries the Kingdom entered into the personal union with the Spaniard and Bourbon crowns, preserving however its substantial independence until 1816. Although today an Autonomous Region of the Republic of Italy, it has its own distinct culture.

Sicily is both the largest region of the modern state of Italy and the largest island in the Mediterranean Sea. Its central location and natural resources ensured that it has been considered a crucial strategic location due in large part to its importance for Mediterranean trade routes.[2] For example, with Cicero and al-Idrisi describing respectively Syracuse and Palermo as the greatest and most beautiful cities of the Hellenic World and of the Middle Ages.[3][4]

The economic history of rural Sicily has focused on its "latifundium economy" caused by the centrality of large, originally feudal, estates used for cereal cultivation and animal husbandry that developed in the 14th century and persisted until World War II.

At times, the island has been at the heart of great civilizations, at other times it has been nothing more than a colonial backwater. Its fortunes have often waxed and waned depending on events out of its control, in earlier times a magnet for immigrants, in later times a land of emigrants.

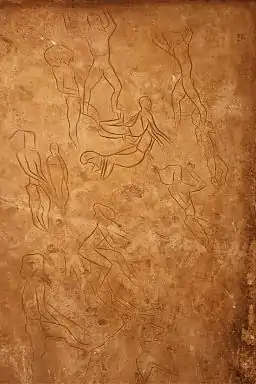

Prehistory

- See also: Prehistory of Sicily

The indigenous peoples of Sicily, long absorbed into the population, were tribes known to ancient Greek writers as the Elymians, the Sicani and the Siculi or Sicels (from which the island derives its name). Of these, the last was clearly the latest to arrive and was related to other Italic peoples of southern Italy, such as the Italoi of Calabria, the Oenotrians, Chones, and Leuterni (or Leutarni), the Opicans, and the Ausones. It is possible, however, that the Sicani were originally an Iberian tribe. The Elymi, too, may have distant origins from outside Italy, in the Aegean Sea area. The recent discoveries of dolmens dating to the second half of the third millennium BC, seem to open up new horizons on the composite cultural panorama of primitive Sicily.

It is a well-known fact that this region went through quite an intricate prehistory, so much so that it is difficult to move about amongst the muddle of peoples that have followed each other. The impact of two influences, however, remains clear: the Europeans coming from the North-West – for example, the Proto-Celtic peoples of Beaker culture (bearers of the dolmens culture, recently discovered in this island and dating back to the neolithic Bronze Age), and the Mediterranean influence with a clear oriental matrix.[5] Complex urban settlements become increasingly evident from around 1300 BC.

From the 11th century BC, Phoenicians begin to settle in western Sicily, having already started colonies on the nearby parts of North Africa. Within a century, we find major Phoenician settlements at Soloeis (Solunto), present day Palermo and Motya (an island near present-day Marsala). As Phoenician Carthage grew in power, these settlements came under its direct control.

Classical Age

Greek period

Sicily was colonized by Greeks in the 8th century BC. Initially, this was restricted to the eastern and southern parts of the island. The most important colony was established at Syracuse in 734 BC. Other important Greek colonies were Gela, Akragas, Selinunte, Himera, Kamarina and Zancle or Messene (modern-day Messina, not to be confused with the ancient city of Messene in Messenia, Greece). These city-states were an important part of classical Greek civilization, which included Sicily as part of Magna Graecia – both Empedocles and Archimedes were from Sicily.

These Greek city-states enjoyed long periods of democratic government, but in times of social stress, in particular, with constant warring against Carthage, tyrants occasionally usurped the leadership. The more famous include: Gelo, Hiero I, Dionysius the Elder and Dionysius the Younger.

As the Greek and Phoenician communities grew more populous and more powerful, the Sicels and Sicanians were pushed further into the centre of the island. By the 3rd century BC, Syracuse was the most populous Greek city in the world. Sicilian politics was intertwined with politics in Greece itself, leading Athens, for example, to mount the disastrous Sicilian Expedition in 415 BC during the Peloponnesian War.

In Greek mythology, the goddess Athena threw Mount Aitna onto the island of Sicily and upon either the gigante Enceladus or Typhon during the giants' war against the gods.[6]

The Greeks came into conflict with the Punic trading communities, by now effectively protectorates of Carthage, with its capital on the African mainland not far from the southwest corner of the island. Palermo was a Carthaginian city, founded in the 8th century BC, named Zis or Sis ("Panormos" to the Greeks). Hundreds of Phoenician and Carthaginian grave sites have been found in a necropolis over a large area of Palermo, now built over, south of the Norman palace, where the Norman kings had a vast park.

In the far west, Lilybaeum (now Marsala) was never thoroughly Hellenized. In the First and Second Sicilian Wars, Carthage was in control of all but the eastern part of Sicily, which was dominated by Syracuse. However, the dividing line between the Carthaginian west and the Greek east moved backwards and forwards frequently in the ensuing centuries.

Punic Wars

The constant warfare between Carthage and the Greek city-states eventually opened the door to an emerging third power. In the 3rd century BC, the Messanan Crisis motivated the intervention of the Roman Republic into Sicilian affairs, and led to the First Punic War between Rome and Carthage.[7] The Carthaginians sent forces to Hiero II, the military leader of the Greek city-states. The Romans fought for the Mamertines of Messina and, Rome and Carthage declared war on each other for the control of Sicily. This led to a war based mainly on the water, which served as an advantage to the Carthaginians, as they were led by Hamilcar, a general who earned his surname Barca (meaning lightning) due to his fast attacks on Roman supply lines. Romans attempted to hide the weakness in their navy by using large moveable planks to invade enemy ships and forcing hand to hand combat, but they still struggled due to the lack of a talented general. Hamilcar and his mercenaries struggled to receive additional aid and reinforcements, as the Carthaginian government hoarded their wealth due to greed and belief that Hamilcar could win on his own.[8] His victory at Drepana in 249 BC was his last, as he was forced to withdraw. In 241 BC, after the Romans adapted better to battle at sea, the Carthaginians surrendered. By the end of the war in (242 BC), and with the death of Hiero II, all of Sicily except Syracuse was in Roman hands, becoming Rome's first province outside of the Italian peninsula.

Hamilcar died in combat in 228 BC, and following the death of his son Hasdrubal, his third son Hannibal took control of the military. He followed a more aggressive path, laying siege to Saguntum, a city allied to Rome. This action started the second war, in which Hannibal took many early victories in Northern Italy. However, like his farther in the first war, a lack of reinforcements and support from the Carthaginians put his forces at a disadvantage. Additionally, Roman general Scipio realized that attacking Carthage itself would force Hannibal to recall his troops. Following the loss at the Battle of Zama in 202, Hannibal pushed the senate to surrender. The success of the Carthaginians during most of the Second Punic War encouraged many of the Sicilian cities to revolt against Roman rule. Rome sent troops to put down the rebellions (it was during the siege of Syracuse that Archimedes was killed). Carthage briefly took control of parts of Sicily, but in the end was driven off. Many Carthaginian sympathizers were killed - in 210 BC the Roman consul M. Valerius told the Roman Senate that "no Carthaginian remains in Sicily".[8]

The Third and final war was the shortest of the three, being the most one sided as well. Carthage waged war against Numidia, an ancient kingdom located modern day Algeria, and upon losing had to pay additional war debts. The Roman Senate expected to be asked for permission, and decided that Carthage posed too much of a threat. After the Carthaginians refused to dismantle the city in 149 BC, the Third Punic War began. The conflict lasted only three years, as the city was besieged during the entire conflict until the city fell and was sacked by the Romans. The power of the Roman Empire expanded largely due to these three wars, and allowed for a prolonged control of Sicily, an incredibly important piece to the Roman empire for hundreds of years.[9]

Roman Period

For the next 600 years, Sicily was a province of the Roman Republic and later Empire. It was something of a rural backwater, important chiefly for its grain fields, which were a mainstay of the food supply for the city of Rome until the annexation of Egypt after the Battle of Actium largely did away with that role. The empire made little effort to Romanize the region, which remained largely Greek. One notable event of this period was the notorious misgovernment of Verres, as recorded by Cicero in 70 BC in his oration, In Verrem. Another was the Sicilian revolt under Sextus Pompeius, which liberated the island from Roman rule for a brief period.

A lasting legacy of the Roman occupation, in economic and agricultural terms, was the establishment of the large landed estates, often owned by distant Roman nobles (the latifundia).

Despite its largely neglected status, Sicily was able to make a contribution to Roman culture through the historian Diodorus Siculus and the poet Calpurnius Siculus. The most famous archeological remains of this period are the mosaics of a nobleman's villa in present-day Piazza Armerina. An inscription from Hadrian's reign lauds the emperor as "The Restorer of Sicily", although it is not known what he did to earn this accolade.

It was also during this period that we find one of the first Christian communities in Sicily. Amongst the earliest Christian martyrs were the Sicilians Saint Agatha of Catania and Saint Lucy of Syracuse.

Early Middle Ages

Germanic and Byzantine period

- See also: History of Byzantine Sicily

As the Roman Empire was falling apart, a tribe of Franks conquered Syracuse in 280 AD; subsequently a Germanic tribe known as the Vandals took Sicily in 440 AD under the rule of their king Genseric. The Vandals had entered the Empire crossing the Rhine the last night of 406 with three other tribes. They were in Gaul until October 409 when they entered Spain where they remained until 429 crossing over to North Africa. The Romans, unable to defeat them, ceded two Mauretanian provinces and the western half of Numidia in 435. However, in October 439 they seized the rest of the Roman provinces, inserting themselves as an important power in western Europe.[10] After the sacking of Rome in 455 the Vandals seized Corsica and Sardinia which they kept until the end of their kingdom in 533. In 476 Odoacer gained most of Sicily for the payment of tribute to the Vandals.[11] In 491 Theodoric gained control over the entire island after repulsing a Vandal invasion and seizing their remaining outpost Lilybaeum on the western tip of the island.[12]

The Gothic War took place between the Ostrogoths and the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire. Sicily was the first part of Italy to be taken under general Belisarius who was commissioned by Eastern Emperor Justinian I.[13] Sicily was used as a base for the Byzantines to conquer the rest of Italy, with Naples, Rome, Milan and the Ostrogoth capital Ravenna falling within five years.[14] However, a new Ostrogoth king, Totila, drove down the Italian peninsula, plundering and conquering Sicily in 550. Totila, in turn, was defeated and killed in the Battle of Taginae by the Byzantine general Narses in 552.[14]

When Ravenna fell to the Lombards in the middle of the 6th century, Syracuse became Byzantium's main western outpost. Latin was gradually supplanted by Greek as the national language and the Greek rites of the Eastern Church were adopted.[15]

The Byzantine Emperor Constans II decided to move from the capital Constantinople to Syracuse in Sicily in 663, the following year he launched an assault from Sicily against the Lombard Duchy of Benevento, which then occupied most of Southern Italy.[16] The rumours that the capital of the empire was to be moved to Syracuse, along with small raids probably cost Constans his life as he was assassinated in 668.[16] His son Constantine IV succeeded him, a brief usurpation in Sicily by Mizizios being quickly suppressed by the new emperor.

From the late 7th century, Sicily joined with Calabria to form the Byzantine Theme of Sicily.[17]

Muslim period

In 826, Euphemius, the commander of the Byzantine fleet of Sicily, forced a nun to marry him. Emperor Michael II caught wind of the matter and ordered that general Constantine end the marriage and cut off Euphemius' nose. Euphemius rose up, killed Constantine and then occupied Syracuse; he in turn was defeated and driven out to North Africa.[18]

There, Euphemius requested the help of Ziyadat Allah, the Aghlabid Emir of Tunisia, in regaining the island; an Islamic army of Arabs, Berbers, Cretan Saracens and Persians was sent.[18] The conquest was a see-saw affair; the local population resisted fiercely and the Arabs suffered considerable dissension and infighting among themselves. It took over a century to complete the conquest (although practically complete by 902, the last Byzantine strongholds held out until 965).[18]

Throughout this reign, continued revolts by Byzantine Sicilians happened, especially in the east, and part of the lands were even re-occupied before being quashed. Agricultural items, such as oranges, lemons, pistachio and sugar cane, were brought to Sicily,[10] the native Christians were allowed nominal freedom of religion with jaziya (tax on non-Muslims, imposed by Muslim rulers) to their rulers for the right to practise their own religion privately. However, the Emirate of Sicily began to fragment as inner-dynasty related quarrels took place between the Muslim regime.[18]

By the 11th century, mainland southern Italian powers were hiring ferocious Norman mercenaries, who were Christian descendants of the Vikings; it was the Normans under Roger I who conquered Sicily from the Muslims.[18] After taking Apulia and Calabria, he occupied Messina with an army of 700 knights. In 1068, Robert Guiscard and his men defeated the Muslims at Misilmeri; but the most crucial battle was the siege of Palermo, which led to Sicily being completely in Norman control by 1091.[19]

Many historians have recently argued that the Norman conquest of Islamic Sicily (1060–91) was the start of the Crusades.[20][21]

Viking Age

In 860, according to an account by the Norman monk Dudo of Saint-Quentin, a Viking fleet, probably under Björn Ironside and Hastein, landed in Sicily, conquering it.[22]

Many Norsemen fought as mercenaries in Southern Italy, including the Varangian Guard led by Harald Hardrada, who later became king of Norway, who conquered Sicily between 1038 and 1040, with the help of Norman mercenaries, under William de Hauteville, who won his nickname Iron Arm by defeating the emir of Syracuse in single combat, and a Lombard contingent, led by Arduin.[23][24] The Varangians were first used as mercenaries in Italy against the Arabs in 936.[25] Runestones were raised in Sweden in memory of warriors who died in Langbarðaland (Land of the Lombards), the Old Norse name for southern Italy.[26]

Later, several Anglo-Danish and Norwegian nobles participated in the Norman conquest of southern Italy, like Edgar the Ætheling, who left England in 1086,[27] and Jarl Erling Skakke, who won his nickname ("Skakke", meaning bent head) after a battle against Arabs in Sicily.[28] On the other hand, many Anglo-Danish rebels fleeing William the Conqueror, joined the Byzantines in their struggle against the Robert Guiscard, duke of Apulia, in Southern Italy.[29]

High Middle Ages

Norman period (1091–1194)

- See also: History of Norman Sicily

Palermo continued on as the capital under the Hauteville. Roger's son, Roger II of Sicily, was ultimately able to raise the status of the island, along with his holds of Malta and Southern Italy to a kingdom in 1130.[19][30] During this period, the Kingdom of Sicily was prosperous and politically powerful, becoming one of the wealthiest states in all of Europe; even wealthier than England.[1]

The Siculo-Norman kings relied mostly on the local Sicilian population for the more important government and administrative positions. For the most part, initially Greek, Arabic and Latin were used as languages of administration while Norman was the language of the royal court.[31] Significantly, immigrants from France, England, North Europe, Northern Italy and Campania arrived during this period and linguistically the island would eventually become Latinised, in terms of church it would become completely Roman Catholic, previously under the Byzantines it had been more Eastern Christian.[32]

The most significant changes that the Normans were to bring to Sicily were in the areas of religion, language and population. Almost from the moment that Roger I controlled much of the island, immigration was encouraged from Northern Europe, France, Northern Italy and Campania. For the most part, these consisted of Lombards who were Vulgar Latin variety-speaking and more inclined to support the Western church. With time, Sicily would become overwhelmingly Roman Catholic and a new vulgar Latin idiom would emerge that was distinct to the island.

Roger II's grandson, William II (also known as William the Good) reigned from 1166 to 1189. His greatest legacy was the building of the Cathedral of Monreale, perhaps the best surviving example of Siculo-Norman architecture. In 1177, he married Joan of England (also known as Joanna). She was the daughter of Henry II of England and the sister of Richard the Lion Heart.

When William died in 1189 without an heir, this effectively signalled the end of the Hauteville succession. Some years earlier, Roger II's daughter, Constance of Sicily (William II's aunt) had been married off to Henry who was son of Emperor Frederick I and would later become Emperor Henry VI, meaning that the crown now legitimately transferred to him. Such an eventuality was unacceptable to the local barons, and they voted in Tancred of Sicily, an illegitimate grandson of Roger II. During his reign Tancred was able to put down rebellions, defeat an invasion by Henry VI and capture Empress Constance, but Pope Celestine III forced him to release her.

Hohenstaufen reign (1194–1266)

Tancred died in 1194, just as Henry VI and Constance were travelling down the Italian peninsula to claim their crown. Henry rode into Palermo at the head of a large army unopposed and thus ended the Siculo-Norman Hauteville dynasty, replaced by the south German (Swabian) Hohenstaufen. Just as Henry VI was being crowned as King of Sicily in Palermo, Constance gave birth to Frederick II (sometimes referred to as Frederick I of Sicily).

Frederick was raised in Palermo and, like his grandfather Roger II, was passionate about science, learning and literature. He created one of the earliest universities in Europe (in Naples), wrote a book on falconry (De arte venandi cum avibus, one of the first handbooks based on scientific observation rather than medieval mythology). He instituted far-reaching law reform formally dividing church and state and applying the same justice to all classes of society, and was the patron of the Sicilian School of poetry, the first time an Italianate form of vulgar Latin was used for literary expression, creating the first standard that could be read and used throughout the peninsula.

Many repressive measures, passed by Frederick II, were introduced in order to please the Popes who could not tolerate Islam being practiced in the heart of Christendom,[33] which resulted in a rebellion of Sicily's Muslims.[34] This in turn triggered organized resistance and systematic reprisals[35] and marked the final chapter of Islam in Sicily. The Muslim problem plagued Hohenstaufen rule in Sicily under Henry VI and his son Frederick II. The rebellion abated, but direct papal pressure induced Frederick to transfer all his Muslim subjects deep into the Italian hinterland, to Lucera.[34] In 1224, Frederick II, Holy Roman Emperor and grandson of Roger II, expelled the few remaining Muslims from Sicily.[36]

Frederick was succeeded firstly by his son, Conrad, and then by his illegitimate son, Manfred, who essentially usurped the crown (with the support of the local barons) while Conrad's son, Conradin was still quite young. A unique feature of all the Swabian kings of Sicily, perhaps inherited from their Siculo-Norman forefathers, was their preference in retaining a regiment of Saracen soldiers as their personal and most trusted regiments. Such a practice, amongst others, ensured an ongoing antagonism between the papacy and the Hohenstaufens. The Hohenstaufen rule ended with the death of Manfredi at the battle of Benevento (1266).

Late Middle Ages

Angevins and the Sicilian Vespers

Throughout Frederick's reign, there had been substantial antagonism between the Kingdom and the Papacy, which was part of the wider Guelph Ghibelline conflict. This antagonism was transferred to the Hohenstaufen house, and ultimately against Manfred.

In 1266, Charles I, duke of Anjou, with the support of the Church, led an army against the Kingdom. They fought at Benevento, just to the north of the Kingdom's border. Manfred was killed in battle and Charles was crowned King of Sicily by Pope Clement IV.

Growing opposition to French officialdom and high taxation led to an insurrection in 1282 (the Sicilian Vespers), which was successful with the support of Peter III of Aragón, who was crowned King of Sicily by the island's barons. Peter III had previously married Manfred's daughter, Constance, and it was for this reason that the Sicilian barons effectively invited him. This victory split the Kingdom in two, with Charles continuing to rule the mainland part (still known as the Kingdom of Sicily as well).

The ensuing War of the Sicilian Vespers lasted until the peace of Caltabellotta in 1302, although it was to continue on and off for a period of 90 years. With two kings both claiming to be the King of Sicily, the separate island kingdom became known as the Kingdom of Trinacria. It is this split that ultimately led to the creation of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies some 500 years on.

Aragonese period

- See also: History of Aragonese Sicily

Peter III's son, Frederick III of Sicily (also known as Frederick II of Sicily) reigned from 1298 to 1337. For the whole of the 14th century, Sicily was essentially an independent kingdom, ruled by relatives of the kings of Aragon, but for all intents and purposes they were Sicilian kings. The Sicilian parliament, already in existence for a century, continued to function with wide powers and responsibilities.

During this period, a sense of a Sicilian people and nation emerged, that is to say, the population was no longer divided between Greek, Arab and Latin peoples. Catalan and Aragonese were the languages of the royal court, and Sicilian was the language of the parliament and the general citizenry. These circumstances continued until 1409 when because of failure of the Sicilian line of the Aragonese dynasty, the Sicilian throne became part of the Crown of Aragon.

The island's first university was founded at Catania in 1434. Antonello da Messina is Sicily's greatest artist from this period.

Spanish period

- See also: History of Spanish Sicily

With the union of the crowns of Castile and Aragon in 1479, Sicily was ruled directly by the kings of Spain via governors and viceroys. In the ensuing centuries, authority on the island was to become concentrated among a small number of local barons.

The viceroy had to overcome the distance and poor communication with the royal court in Madrid. It proved almost impossible for the Spanish viceroys both to comply with the demands of the crown and to satisfy the aspirations of the Sicilians – a situation also apparent in Spain's colonies in Latin America. The viceroys secured territorial control and sought to guarantee the loyalty of vassals by distributing patronage in the form of offices and grants in the name of the king. The monarchy, however, also exercised its power through royal councils and independent entities, such as the agents of the Inquisition and visitadores or inspectors. Local spheres of royal influence were never clearly defined, and various local political entities within the viceregal system competed for power, often rendering Sicily ungovernable.[37]

The 16th century was a golden age for Sicily's wheat exports. Inflation, rapid population growth, and international markets brought economic and social changes. In the 17th century, Sicily's silk exports overtook its wheat exports. Internal colonization and the foundation of new settlements by feudal aristocrats in Sicily was significant from 1590 to 1650, involving the redistribution of population away from the larger towns back to the countryside.[38]

The baronage took advantage of increasing population and demand to build new estates, based mostly on wheat, and the new villages were inhabited mostly by landless laborers. The foundation of estates was a means toward social and political prominence for many families. The townspeople initially welcomed the process as a way of alleviating poverty by draining off surplus population, but at the same time it led to a decline in their political and administrative control of the countryside.[38]

Sicily suffered a ferocious outbreak of the Black Death in 1656, followed by a damaging earthquake in the east of the island in 1693. Sicily was frequently attacked by Barbary pirates from North Africa. The subsequent rebuilding created the distinctive architectural style known as Sicilian Baroque. Periods of rule by the house of Savoy (1713–1720) and then the Austrian Habsburgs led to union (1734) with the Bourbon-ruled Kingdom of Naples, under the rule of Don Carlos of Bourbon (later Charles III of Spain).

Bourbon period

- See also: History of Bourbon Sicily

The Bourbon kings officially resided in Naples, except for a brief period during the Napoleonic Wars between 1806 and 1815, when the royal family lived in exile in Palermo. The Sicilian nobles welcomed British military intervention during this period and a new constitution was developed specifically for Sicily based on the Westminster model of government. The British were committed to preserving the security of the Kingdom of Sicily so as to keep Mediterranean sea routes open against the French. The British dispatched several expeditions of troops between 1806 and 1815 and built strong fortifications around Messina[39]

The Kingdoms of Naples and Sicily were officially merged in 1816 by Ferdinand I to form the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies.[40] The accession of Ferdinand II as king of the Two Sicilies in 1830 was hailed by Sicilians; they dreamed that autonomy would be returned to the island and the problems of poverty and maladministration of justice would be tackled by the count of Syracuse, the king's brother and lieutenant in Sicily.

The royal government in Naples saw the problem of Sicily as being purely administrative, a question of making existing institutions function properly. Neapolitan ministers had no interest in serious reforms. Ferdinand's failure, leading to disillusion and the revolt of 1837, was due mainly to his making no attempt to gain support in the Sicilian middle class, with which he could have faced the power of the baronage.

Simmering discontent with Bourbon rule and hopes of Sicilian independence led to major revolts in 1820 and 1848 against Bourbon denial of constitutional government. The 1848 revolution resulted in a sixteen-month period of independence from the Bourbons before its armed forces took back control of the island on 15 May 1849. The city of Messina long harbored proponents of independence throughout the 19th century, and its urban Risorgimento leaders arose out of a diverse milieu comprising artisans, workers, students, clerics, Masons, and sons of English, Irish, and other settlers.[41]

The 1847-48 unrest enjoyed wide support in Messina and produced an organized structure, and consciousness of the need to link the struggle to the whole of Sicily. The insurgents briefly gained control of the city but, despite bitter resistance, the Bourbon army was victorious and suppressed the revolt. This suppression resulted in further oppression, created a diaspora of Messinian and Sicilian revolutionaries outside Sicily and locked Sicily under the control of the reactionary government. The bombardments of Messina and Palermo earned Ferdinand II the name "King Bomba".[41]

Modern era

- See also: History of Sicily (1860–1946)

Unification of Italy period

Sicily was merged with the Kingdom of Sardinia in 1860 following the expedition of Giuseppe Garibaldi's Mille; after the Dictatorship of Garibaldi the annexation was ratified by a popular plebiscite. The Kingdom of Sardinia became in 1861 the Kingdom of Italy, in the context of the Italian Risorgimento.

However, local elites across the island systematically opposed and nullified efforts of the national government to modernize the traditional economy and political system. For example, they frustrated government efforts to set up new town councils, new police forces, and a liberal judicial system. Furthermore, repeated revolts showed a degree of unrest among the peasants.[42]

In 1866, Palermo revolted against Italy. The city was bombed by the Italian navy, which disembarked on September 22 under the command of Raffaele Cadorna. Italian soldiers summarily executed the civilian insurgents, and once again took possession of the island.

A limited, but long guerrilla campaign against the unionists (1861–1871) took place throughout southern Italy, and in Sicily, inducing the Italian governments to a severe military response. These insurrections were unorganized, and were considered by the Government as operated by "brigands" ("Brigantaggio"). Ruled under martial law for several years, Sicily (and southern Italy) was the object of a harsh repression by the Italian army that summarily executed thousands of people, made tens of thousands prisoners, destroyed villages, and deported people.

Emigration

The Sicilian economy did not adapt easily to unification, and in particular competition by Northern industry made attempts at industrialization in the South almost impossible. While the masses suffered by the introduction of new forms of taxation and, especially, by the new Kingdom's extensive military conscription, the Sicilian economy suffered, leading to an unprecedented wave of emigration.

The reluctance of Sicilian men to allow women to take paid work meant that women usually remained at home, their seclusion often increased due to the restrictions of mourning. Despite such restrictions, women carried out a variety of important roles in nourishing their families, selecting wives for their sons, and helping their husbands in the field.[43]

In 1894, labour agitation through the radical left-wing Fasci Siciliani (Sicilian Workers Leagues) again led to the imposition of martial law.

Mafia

The Mafia became an essential part of the social structure in the late 19th century because of the inability of the Italian state to impose its concept of law and its monopoly on violence in a peripheral region. The decline of feudal structures allowed a new middle class of violent peasant entrepreneurs to emerge who profited from the sale of baronial, Church, and common land and established a system of clientage over the peasantry. The government was forced to compromise with these "bourgeois mafiosi," who used violence to impose their law, manipulated the traditional feudal language, and acted as mediators between society and the state.[44]

Early 20th century and Fascist period

Ongoing government neglect in the late 19th century ultimately enabled the establishment of organized crime networks, commonly known as "Cosa Nostra" or the Mafia. The Sicilian mafia during the fascism was fought by the government of Benito Mussolini, who sent the island the prefect Cesare Mori. These were gradually able to extend their influence across all sectors over much of the island (and many of its operatives also emigrated to other countries, particularly the United States). After Mussolini came to power in the 1920s, he launched a fierce crackdown on organized crime, but they recovered quickly following the Allied invasion of Sicily in July 1943, during World War II, once the Allies freed imprisoned Mafia leaders under the mistaken notion that they were political prisoners.[45]

Cosa Nostra remains a secret criminal organization with a state-like structure. It utilizes violence as an instrument of control, executing members who break its rules as well as outsiders who threaten or fail to cooperate with the organization. In 1984, the Italian government initiated an anti-Mafia policy that sought to eliminate the organization by prosecuting its leaders.[44]

Although Sicily fell to the Allied armies with relatively little fighting, the German and Italian forces escaped to the mainland largely intact. Control of Sicily gave the Allies a base from which to advance northward through Italy. Furthermore, it proved a valuable training ground for large-scale amphibious operations–lessons that would be essential for the invasion of Normandy.[46]

Post-war period

Following some political agitation, Sicily became an autonomous region in 1946 under the new Italian constitution, with its own parliament and elected President.

The latifundia (large feudal agricultural estates) were abolished by sweeping land reform mandating smaller farms in 1950–1962, funded from the Cassa per il Mezzogiorno, the Italian government's development Fund for the South (1950–1984).[47]

Sicily returned to the headlines in 1992, however, when the assassination of two anti-mafia magistrates, Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino triggered a general upheaval in Italian political life.

In the 21st century Sicily, and its surrounding islets, has become a target destination for migrants coming from North Africa and the site of people-smuggling operations.

References

- John Julius, Norwich (1992). The Normans in Sicily: The Normans in the South 1016-1130 and the Kingdom in the Sun 1130-1194. Penguin Global. ISBN 978-0-14-015212-8.

- "Sicily". KeyItaly.com. 20 November 2007.

- "Sicilia's Urbs of Syracusa". AncientWorlds.net. 20 November 2007. Archived from the original on 21 October 2007.

- Durant, Will, (2011) The Story of Civilization - The Age of Faith, Simon and Schuster, New York, ISBN 9781451647617

- Salvatore Piccolo, Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily, op. cit., p. 31.

- "Enceladus: Giant of Mt. Etna in Sicily", Theoi.

- Cary, M. (1922). "HISTORICAL REVISIONS. XXI.—The Origins of the Punic Wars". History. 7 (26): 109–111. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1922.tb01629.x. ISSN 0018-2648. JSTOR 24399923.

- "Punic Wars". Ancient History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2020-05-06.

- Salas, Charles G. (1996). "Ralegh and the Punic Wars". Journal of the History of Ideas. 57 (2): 195–215. doi:10.2307/3654095. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 3654095.

- Privitera, Joseph (2002). Sicily: An Illustrated History. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0-7818-0909-2.

- John Moorhead, Theodoric in Italy, 1992, p. 9 ISBN O-19-81478-3

- Herwig Wolfram, History of the Goths,1988, p. 291 ISBN 978-0520069831

- Hearder, Harry (1990). Italy: A Short History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33719-9.

- "Gothic War: Byzantine Count Belisarius Retakes Rome". Historynet.com. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 2 November 2007.

- Smith, Denis Mack, (1968) A History of Sicily: Medieval Sicily 800–1713, Chatto & Windus, London, ISBN 0-7011-1347-2

- "Syracuse, Sicily". TravelMapofSicily.com. 7 October 2007.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium. Oxford University Press. pp. 1891–1892. ISBN 978-0-19-504652-6.

- "Brief history of Sicily" (PDF). Archaeology.Stanford.edu. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 June 2007.

- "Chronological - Historical Table Of Sicily". In Italy Magazine. 7 October 2007. Archived from the original on 27 July 2016. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- Powell (2007)

- Paul E. Chevedden, " The Islamic View and the Christian View of the Crusades: A New Synthesis," History, April 2008, Vol. 93 Issue 310, pp 181-200

- Haywood, John. Northmen. Head of Zeus.

- Carr, John. Fighting Emperors of Byzantium. Pen and Sword. p. 177.

- Hill, Paul. The Norman Commanders: Masters of Warfare 911-1135. Pen and Sword. p. 18.

- Ullidtz, Per. 1016 The Danish Conquest of England. BoD – Books on Demand. p. 936.

- 2. Runriket - Täby Kyrka Archived 2008-06-04 at Archive.today, an online article at Stockholm County Museum, retrieved July 1, 2007.

- Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, p. 217; Florence of Worcester, p. 145

- Orkneyinga Saga, Anderson, Joseph, (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1873), FHL microfilm 253063., p. 134, 139, 144-145, 149-151, 163, 193.

- Translation based on Chibnall (ed.), Ecclesiastical History, vol. ii, pp. 203, 205

- "Classical and Medieval Malta (60-1530)". AboutMalta.com. 7 October 2007.

- Johns, Jeremy (2002-10-07). Arabic Administration in Norman Sicily: The Royal Diwan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139440196.

- "Sicilian Peoples: The Normans". BestofSicily.com. 7 October 2007.

- N.Daniel: The Arabs; op cit; p.154.

- A.Lowe: The Barrier and the bridge, op cit;p.92.

- Aubé, Pierre (2001). Roger Ii De Sicile - Un Normand En Méditerranée. Payot.

- Julie Taylor. Muslims in Medieval Italy: The Colony at Lucera Archived 2005-03-18 at the Wayback Machine. Lanham, Md.: Lexington Books. 2003.

- Fernando Ciaramitaro, "Virrey, Gobierno Virreinal y Absolutismo: El Caso de la Nueva España y del Reino de Sicilia," ["Viceroy, government, and absolutism: the case of New Spain and the Sicilian kingdom"] Studia Historica: Historia Moderna, 2008, Vol. 30, pp 235-271

- Francesco Benigno, "Vecchio e Nuovo Nella Sicilia del Seicento: Il Ruolo Della Colonizzazione Feudale", [Old and new in 17th-century Sicily: the role of feudal colonization] Studi Storici (1986), Vol. 27 Issue 1, pp 93-107

- W. H. Clements, "The Defences of Sicily, 1806-1815," Journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, Autumn 2009, Vol. 87 Issue 351, pp 256-272

- The term had already come into use in the 18th century

- Correnti, (2002)

- L. J. Riall, "Liberal policy and the control of public order in western Sicily 1860-1862," Historical Journal, June 1992, Vol. 35 Issue 2, pp 345-68

- Bernard Cook, "Sicilian Women Peasants in the Nineteenth Century," Consortium on Revolutionary Europe 1750-1850: Selected Papers, 1997, pp 627-638

- Dickie (2004)

- It is a false myth that the Allies cooperated with the Mafia during the war. Salvatore Lupo,"The Allies and the Mafia," Journal of Modern Italian Studies, March 1997, Vol. 2 Issue 1, pp 21-33

- Atkinson (2008)

- John Paul Russo, "The Sicilian Latifundia," Italian Americana, March 1999, Vol. 17 Issue 1, pp 40-57

Further reading

- Abulafia, David. The Two Italies: economic relations between the Norman kingdom of Sicily and the northern communes (Cambridge UP, 2005).

- Atkinson, Rick. The Day of Battle: The War in Sicily and Italy, 1943-1944 (2007)

- Baedeker (1912), "Sicily: Historical Notice", Southern Italy and Sicily (16th ed.), Leipzig: Leipzig, Baedeker, pp. 290–303

- Blok Anton. The Mafia of a Sicilian Village 1860-1960: A Study of Violent Peasant Entrepreneurs (1988)

- Chiarelli, Leonard C. A history of Muslim Sicily (Midsea Books, 2018).

- Correnti, Santi. A Short History of Sicily, (2002) Les Éditions Musae, ISBN 2-922621-00-6

- Darby, Graham. "Sicily's British Occupation" History Today (July 2012)(, Vol. 62 Issue 7, pp 28–34; covers 1806 to 1815.

- Davis-Secord, Sarah C. Where Three Worlds Met: Sicily in the Early Medieval Mediterranean. (Cornell UP< 2017). ISBN 978-1-5017-0464-2.

- De Angelis, Franco. Archaic and classical Greek Sicily: a social and economic history (Oxford UP, 2016).

- Dickie, John. Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia (2004), synthesis of Italian scholarship

- Dimico, Arcangelo, Alessia Isopi, and Ola Olsson. "Origins of the Sicilian Mafia: The market for lemons." Journal of Economic History 77.4 (2017): 1083-1115. online

- Domenico, Roy (2002). "Sicily". Regions of Italy: a Reference Guide to History and Culture. Greenwood. ISBN 0313307334.

- Dummett, Jeremy. Sicily: Island of Beauty and Conflict (Bloomsbury, 2020).

- Epstein, S. R. "Cities, Regions and the Late Medieval Crisis: Sicily and Tuscany Compared," Past & Present, Feb 1991, Issue 130, pp 3–50, advanced social history

- Epstein, Stephan R. Island for Itself: Economic Development and Social Change in Late Medieval Sicily (1992). ISBN 978-0521385183

- Finley, M. I. and Dennis Mack Smith. History of Sicily (3 Vols. 1961)

- Finley, M. I., Denis Mack Smith and Christopher Duggan, A History of Sicily (1987) abridged edition online

| title = Encyclopædia Britannica | location = New York | date = 1910 | edition=11th | oclc = 14782424 | via=Internet Archive | chapter = Sicily |pages= 20–35 |author1= Edward Augustus Freeman |author2= Thomas Ashby | title-link = Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition | chapter-url = https://archive.org/stream/encyclopaediabri25chisrich#page/20/mode/1up | ref = CITEREFBritannica1910 }}

- Gabaccia, Donna R. "Migration and Peasant Militance: Western Sicily, 1880-1910," Social Science History, Spring 1984, Vol. 8 Issue 1, pp 67–80 in JSTOR

- Gabaccia, Donna. Militants & Migrants: Rural Sicilians Become American Workers (1988) 239p; covers 1860 to 20th century

- Granara, William. Narrating Muslim Sicily: War and Peace in the Medieval Mediterranean World (Bloomsbury, 2019).

- Harpster, Matthew. "Sicily: A Frontier in the Centre of the Sea?." Al-Masāq 31.2 (2019): 158-170. online

- Jäckh, Theresa, and Mona Kirsch, eds. Urban dynamics and transcultural communication in medieval Sicily (Wilhelm Fink, 2017).

- Jonasch, Melanie, ed. The Fight for Greek Sicily: Society, Politics, and Landscape (Oxbow Books, 2020).

- Kantorowicz, Ernst. Frederick the Second, 1194–1250 (Frederick Ungar, 1957).

- Mallette, Karla. The Kingdom of Sicily, 1100-1250: A Literary History (U of Pennsylvania Press, 2011).

- Matthew, Donald. The Norman Kingdom of Sicily (2008) excerpt

- Militello, Paolo. "The Historiography on Early Modern Age Sicily Between the 20th and 21st Centuries." Mediterranea-ricerche storiche 36 (2016) 101–118 online.

- Newark, Tim. "Pact with the Devil?" History Today (April 2007), Vol. 57 Issue 4, pp32–38' US deals with Mafia 1942-1943.

- Norwich, John Julius. The Normans in Sicily, (1992) ISBN 0-14-015212-1

- Pfuntner, Laura. Urbanism and empire in Roman Sicily (U of Texas Press, 2019).

- Piccolo, Salvatore. Ancient Stones: The Prehistoric Dolmens of Sicily, (2013). Thornham/Norfolk: Brazen Head Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9565106-2-4.

- Powell, James M. The Crusades, the Kingdom of Sicily, and the Mediterranean (Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Company. (2007). 300pp. ISBN 978-0-7546-5917-4

- Ramm, Agatha. "The Risorgimento in Sicily: Recent Literature," English Historical Review (1972) 87#345 pp. 795–811 in JSTOR

- Reeder, Linda. Widows in White: Migration and the Transformation of Rural Italian Women, Sicily, 1880-1920. (2003), 322pp ISBN 0-8020-8525-3

- Riall, Lucy. Sicily and the Unification of Italy: Liberal Policy & Local Power, 1859-1866 (1998), 252pp

- Runciman, Steven. The Sicilian Vespers (1958) online

- Schneider, Jane. Culture and Political Economy in Western Sicily (1976)

- Smith, Denis Mack. Medieval Sicily, 800–1713 (1968).

- Takayama, Hiroshi. Sicily and the Mediterranean in the Middle Ages (2019) excerpts

- Vincent, Benjamin (1910), "Sicily", Haydn's Dictionary of Dates (25th ed.), London: Ward, Lock & Co., hdl:2027/uc2.ark:/13960/t41r6xh8t

- Williams, Isobel. Allies and Italians under Occupation: Sicily and Southern Italy, 1943-45 (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013). online review

in Italian

- Valguarnera, Mariano (1614). Discorso dell'origine ed antichità di Palermo, e de' primi abitatori della Sicilia, e dell'Italia. Palermo: Giovanni Battista Maringo. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- Agati, Salvatore. Carlo V e la Sicilia, Catania, Giuseppe Maimone Editore, 2009, ISBN 978-88-7751-287-1.

- Jean Huré. Storia della Sicilia, Brancato Editore, 2005 ISBN 88-8031-078-X

- Gallo, Francesca. Sicilia austriaca. Le istruzioni ai viceré, 1719-1734, Napoli, Jovene, 1994.

- Gibilaro, Giovanni. Sicilia austriaca. 1720-1735, 1996.

- D. Ligresti, Sicilia aperta (secoli XV-XVII). Mobilità di uomini e di idee, Palermo, Quaderni Mediterranea Ricerche Storiche, 2006

- Santagati, Luigi. Storia dei Bizantini di Sicilia, Edizioni Lussografica 2012, ISBN 978-88-8243-201-0

- Renda, Francesco. Storia della Sicilia, (3 Vol.) Sellerio, 2006, ISBN 978-8838919145

- Riccobene, Luigi. Sicilia ed Europa dal 1700 al 1815, (3 vol), Sellerio, Palermo 1996

- Santuccio, Salvatore. Governare la città. Territorio, amministrazione e politica a Siracusa (1817-1865), Ed. Franco Angeli, Milano, 2010 , ISBN 9788856830828

- Tusa, Sebastiano. La Sicilia nella Preistorica. Sellerio, Palermo 1999

.JPG.webp)