Dynasties in Chinese history

Dynasties in Chinese history, or Chinese dynasties, were hereditary monarchical regimes that ruled over China during much of its history. From the inauguration of dynastic rule by Yu the Great in circa 2070 BC to the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor on 12 February 1912 in the wake of the Xinhai Revolution, China was ruled by a series of successive dynasties.[lower-alpha 1][lower-alpha 2] Dynasties of China were not limited to those established by ethnic Han—the dominant Chinese ethnic group—and its predecessor, the Huaxia tribal confederation, but also included those founded by non-Han peoples.[6]

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ANCIENT | ||||||||

| Neolithic c. 8500 – c. 2070 BC | ||||||||

| Xia c. 2070 – c. 1600 BC | ||||||||

| Shang c. 1600 – c. 1046 BC | ||||||||

| Zhou c. 1046 – 256 BC | ||||||||

| Western Zhou | ||||||||

| Eastern Zhou | ||||||||

| Spring and Autumn | ||||||||

| Warring States | ||||||||

| IMPERIAL | ||||||||

| Qin 221–207 BC | ||||||||

| Han 202 BC – 220 AD | ||||||||

| Western Han | ||||||||

| Xin | ||||||||

| Eastern Han | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms 220–280 | ||||||||

| Wei, Shu and Wu | ||||||||

| Jin 266–420 | ||||||||

| Western Jin | ||||||||

| Eastern Jin | Sixteen Kingdoms | |||||||

| Northern and Southern dynasties 420–589 | ||||||||

| Sui 581–618 | ||||||||

| Tang 618–907 | ||||||||

| (Wu Zhou 690–705) | ||||||||

| Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms 907–979 |

Liao 916–1125 | |||||||

| Song 960–1279 | ||||||||

| Northern Song | Western Xia | |||||||

| Southern Song | Jin | Western Liao | ||||||

| Yuan 1271–1368 | ||||||||

| Ming 1368–1644 | ||||||||

| Qing 1636–1912 | ||||||||

| MODERN | ||||||||

| Republic of China on mainland 1912–1949 | ||||||||

| People's Republic of China 1949–present | ||||||||

| Republic of China on Taiwan 1949–present | ||||||||

Dividing Chinese history into periods ruled by dynasties is a common method of periodization utilized by scholars.[7] Accordingly, a dynasty may be used to delimit the era during which a family reigned, as well as to describe events, trends, personalities, artistic compositions, and artifacts of that period.[8] For example, porcelain made during the Ming dynasty may be referred to as "Ming porcelain".[9] The word "dynasty" is usually omitted when making such adjectival references.

The longest-reigning orthodox dynasty of China was the Zhou dynasty, ruling for a total length of 789 years, albeit it is divided into the Western Zhou and the Eastern Zhou in Chinese historiography, and its power was drastically reduced during the latter part of its rule.[10] The largest orthodox Chinese dynasty in terms of territorial size was either the Yuan dynasty or the Qing dynasty, depending on the historical source.[11][12][13][14][15][lower-alpha 3]

Chinese dynasties often referred to themselves as "Tiāncháo" (天朝; "Celestial Dynasty" or "Heavenly Dynasty").[19][20] As a form of respect and subordination, Chinese tributary states referred to Chinese dynasties as "Tiāncháo Shàngguó" (天朝上國; "Celestial Dynasty of the Lofty State") or "Tiāncháo Dàguó" (天朝大國; "Celestial Dynasty of the Great State").[21]

Terminology

In the Chinese language, the character "cháo" (朝) originally meant "morning" and "today". Politically, the word is taken to refer to the regime of the incumbent ruler.

The following is a list of terms associated with the concept of dynasty in Chinese historiography:

- cháo (朝): a dynasty

- cháodài (朝代): an era corresponding to the rule of a dynasty

- wángcháo (王朝): while technically referring to royal dynasties, this term is often inaccurately applied to all dynasties, including those whose rulers held non-royal titles such as emperor[22]

- huángcháo (皇朝): generally used for imperial dynasties[22]

History

Start of dynastic rule

As the founder of China's first dynasty, the Xia dynasty, Yu the Great is conventionally regarded as the inaugurator of dynastic rule in China.[23][lower-alpha 1] In the Chinese dynastic system, sovereign rulers theoretically possessed absolute power and private ownership of the realm, even though in practice their actual power was dependent on numerous factors.[24][lower-alpha 4] By tradition, the Chinese throne was inherited exclusively by members of the male line, but there were numerous cases whereby the consort kins came to possess de facto power at the expense of the monarchs.[28][lower-alpha 5] This concept, known as jiā tiānxià (家天下; "All under Heaven belongs to the ruling family"), was in contrast to the pre-Xia notion of gōng tiānxià (公天下; "All under Heaven belongs to the public") whereby leadership succession was non-hereditary.[24][30]

Dynastic transition

The rise and fall of dynasties is a prominent feature of Chinese history. Some scholars have attempted to explain this phenomenon by attributing the success and failure of dynasties to the morality of the rulers, while others have focused on the tangible aspects of monarchical rule.[31] This method of explanation has come to be known as the dynastic cycle.[31][32][33]

Dynastic transitions (改朝換代; gǎi cháo huàn dài) in the history of China occurred primarily through two ways: military conquest and usurpation.[34] The supersession of the Liao dynasty by the Jin dynasty was achieved following a series of successful military campaigns, as was the later unification of China under the Yuan dynasty; on the other hand, the transition from the Eastern Han to the Cao Wei, as well as from the Southern Qi to the Liang dynasty, were cases of usurpation. Oftentimes, usurpers would seek to portray their predecessors as having relinquished the throne willingly—a process called shànràng (禪讓; "voluntary abdication")—as a means to legitimize their rule.[35]

One might incorrectly infer from viewing historical timelines that transitions between dynasties occurred abruptly and roughly. Rather, new dynasties were often established before the complete overthrow of an existing regime.[36] For example, AD 1644 is frequently cited as the year in which the Qing dynasty succeeded the Ming dynasty in possessing the Mandate of Heaven. However, the Qing dynasty was officially proclaimed in AD 1636 by the Emperor Taizong of Qing through renaming the Later Jin established by his father the Emperor Taizu of Qing in AD 1616, while the Ming imperial family would rule the Southern Ming until AD 1662.[37][38] The Ming loyalist Kingdom of Tungning based in Taiwan continued to oppose the Qing until AD 1683.[39] Meanwhile, other factions also fought for control over China during the Ming–Qing transition, most notably the Shun and the Xi dynasties proclaimed by Li Zicheng and Zhang Xianzhong respectively.[40][41][42] This change of ruling houses was a convoluted and prolonged affair, and the Qing took almost two decades to extend their rule over the entirety of China proper.

Similarly, during the earlier Sui–Tang transition, numerous regimes established by rebel forces vied for control and legitimacy as the power of the ruling Sui dynasty weakened. Autonomous regimes that existed during this period of upheaval included, but not limited to, Wei (魏; by Li Mi), Qin (秦; by Xue Ju), Qi (齊; by Gao Tancheng), Xu (許; by Yuwen Huaji), Liang (梁; by Shen Faxing), Liang (梁; by Liang Shidu), Xia (夏; by Dou Jiande), Zheng (鄭; by Wang Shichong), Chu (楚; by Zhu Can), Chu (楚; by Lin Shihong), Yan (燕; by Gao Kaidao), and Song (宋; by Fu Gongshi). The Tang dynasty that superseded the Sui launched a decade-long military campaign to reunify China proper.[43]

Frequently, remnants and descendants of previous dynasties were either purged or granted noble titles in accordance with the Èr Wáng Sān Kè (二王三恪; "two crownings, three respects") system. The latter served as a means for the reigning dynasty to claim legitimate succession from earlier dynasties.[44] For example, the Emperor Xiaojing of Eastern Wei was accorded the title "Prince of Zhongshan" by the Emperor Wenxuan of Northern Qi following the latter's deposition of the former.[45] Similarly, Chai Yong, a nephew of the Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou, was conferred the title "Duke of Chongyi" by the Emperor Renzong of Song; other descendants of the Later Zhou ruling family came to inherit the noble title thereafter.[46]

According to Chinese historiographical tradition, each new dynasty would compose the history of the preceding dynasty, culminating in the Twenty-Four Histories.[47] This tradition was maintained even after the Xinhai Revolution overthrew the Qing dynasty in favor of the Republic of China. However, the attempt by the Republicans to draft the history of the Qing was disrupted by the Chinese Civil War, which resulted in the political division of China into the People's Republic of China on mainland China and the Republic of China on Taiwan.[48]

End of dynastic rule

.jpg.webp)

Dynastic rule in China collapsed in AD 1912 when the Republic of China superseded the Qing dynasty following the success of the Xinhai Revolution.[49][50] While there were attempts after the Xinhai Revolution to reinstate dynastic rule in China, they were unsuccessful at consolidating their rule and gaining political legitimacy.

During the Xinhai Revolution, there were numerous proposals advocating for the replacement of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty by a new dynasty of Han ethnicity. Kong Lingyi (孔令貽), a 76th-generation descendant of Confucius and the holder of Duke Yansheng, was identified as a potential candidate for Chinese emperorship by Liang Qichao.[51] Meanwhile, gentry in Anhui and Hebei supported a restoration of the Ming dynasty under Zhu Yuxun (朱煜勳), the Marquis of Extended Grace.[52] Both suggestions were ultimately rejected.

The Empire of China (AD 1915–1916) proclaimed by Yuan Shikai sparked the National Protection War, resulting in the premature collapse of the regime 101 days later.[53] The Manchu Restoration (AD 1917) was an unsuccessful attempt at reviving the Qing dynasty, lasting merely 11 days.[54] Similarly, the Manchukuo (AD 1932–1945; monarchy since AD 1934), a puppet state of the Empire of Japan during World War II with limited diplomatic recognition, is not regarded as a legitimate regime.[55] Ergo, historians usually consider the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor on 12 February 1912 as the end of the Chinese dynastic system. Dynastic rule in China lasted almost four millennia.[49]

Political legitimacy

China was politically divided during multiple periods in its history, with different regions ruled by different dynasties. These dynasties effectively functioned as separate states with their own court and political institutions. Political division existed during the Three Kingdoms, the Sixteen Kingdoms, the Northern and Southern dynasties, and the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms periods, among others.

Relations between Chinese dynasties during periods of division often revolved around political legitimacy, which was derived from the doctrine of the Mandate of Heaven.[56] Dynasties ruled by ethnic Han would proclaim rival dynasties founded by other ethnicities as illegitimate, usually justified based on the concept of Hua–Yi distinction. On the other hand, many dynasties of non-Han origin saw themselves as the legitimate dynasty of China and often sought to portray themselves as the true inheritor of Chinese culture and history. Traditionally, only regimes deemed as "legitimate" or "orthodox" (正統; zhèngtǒng) are termed cháo (朝; "dynasty"); "illegitimate" or "unorthodox" regimes are referred to as guó (國; usually translated as either "state" or "kingdom"[lower-alpha 6]), even if these regimes were dynastic in nature.[57] The issue of political legitimacy pertaining to some of these dynasties remains contentious in modern academia.

Such legitimacy dispute existed during the following periods:

- Three Kingdoms[58]

- The Cao Wei, the Shu Han, and the Eastern Wu considered themselves legitimate while simultaneously denounced the rivaling claims of others

- The Emperor Xian of Han abdicated in favor of the Emperor Wen of Cao Wei, hence the Cao Wei directly succeeded the Eastern Han in the timeline of Chinese history

- The Western Jin accepted the Cao Wei as the legitimate dynasty of the Three Kingdoms period and claimed succession from it

- The Tang dynasty viewed the Cao Wei as the legitimate dynasty during this period, whereas the Southern Song scholar Zhu Xi proposed treating the Shu Han as legitimate[59][60]

- Eastern Jin and Sixteen Kingdoms[61]

- The Eastern Jin proclaimed itself to be legitimate

- Several of the Sixteen Kingdoms such as the Han Zhao, the Later Zhao, and the Former Qin also claimed legitimacy

- Northern and Southern dynasties[62]

- All dynasties during this period saw themselves as the legitimate representative of China; the Northern dynasties referred to their southern counterparts as "dǎoyí" (島夷; "island dwelling barbarians"), while the Southern dynasties called their northern neighbors "suǒlǔ" (索虜; "barbarians with braids")[63][64]

- Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms[65]

- Having directly succeeded the Tang dynasty, the Later Liang considered itself to be a legitimate dynasty[65]

- The Later Tang regarded itself as the restorer of the earlier Tang dynasty and rejected the legitimacy of its predecessor, the Later Liang[65]

- The Later Jin accepted the Later Tang as a legitimate regime[65]

- The Southern Tang was, for a period of time, considered the legitimate dynasty during the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period[65]

- Modern historiography generally considers the Five Dynasties, as opposed to the contemporary Ten Kingdoms, to be legitimate[65][66]

- Liao dynasty, Song dynasty, and Jin dynasty[67]

- Following the conquest of the Later Jin, the Liao dynasty claimed legitimacy and succession from it[68]

- Both the Northern Song and Southern Song considered themselves to be the legitimate Chinese dynasty

- The Jin dynasty challenged the Song's claim of legitimacy

- The succeeding Yuan dynasty recognized all three in addition to the Western Liao as legitimate Chinese dynasties, culminating in the composition of the History of Liao, the History of Song, and the History of Jin[69][70][71]

- Ming dynasty and Northern Yuan[72]

- The Ming dynasty recognized the preceding Yuan dynasty as a legitimate Chinese dynasty, but asserted that it had succeeded the Mandate of Heaven from the Yuan, thus considering the Northern Yuan as illegitimate

- Northern Yuan rulers maintained the dynastic name "Great Yuan" and claimed Chinese titles continuously until AD 1388 or AD 1402; Chinese titles were restored on several occasions thereafter for brief periods

- The Mongol historian Rashipunsug argued that the Northern Yuan had succeeded the legitimacy from the Yuan dynasty; the Qing dynasty, which later defeated and annexed the Northern Yuan, inherited this legitimacy, thus rendering the Ming as illegitimate[73]

- Qing dynasty and Southern Ming[74]

- The Qing dynasty recognized the preceding Ming dynasty as legitimate, but asserted that it had succeeded the Mandate of Heaven from the Ming, thus refuting the claimed legitimacy of the Southern Ming

- The Southern Ming continued to claim legitimacy until its eventual defeat by the Qing

- The Ming loyalist Kingdom of Tungning in Taiwan denounced the Qing dynasty as illegitimate

- The Joseon dynasty of Korea and the Later Lê dynasty of Vietnam had at various times considered the Southern Ming, instead of the Qing dynasty, as legitimate[75][76]

- The Tokugawa shogunate of Japan did not accept the legitimacy of the Qing dynasty and instead saw itself as the rightful representative of Huá (華; "China"); this narrative served as the basis of Japanese texts such as Chūchō Jijitsu and Kai Hentai[77][78][79]

While periods of disunity often resulted in heated debates among officials and historians over which dynasty could and should be considered orthodox, the Northern Song statesman Ouyang Xiu propounded that such orthodoxy existed in a state of limbo during fragmented periods and was restored after political unification was achieved.[80] From this perspective, the Song dynasty possessed legitimacy by virtue of its ability to end the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period despite not having succeeded the orthodoxy from the Later Zhou. Similarly, Ouyang considered the concept of orthodoxy to be in oblivion during the Three Kingdoms, the Sixteen Kingdoms, and the Northern and Southern dynasties periods.[80]

As most Chinese historiographical sources uphold the idea of unilineal dynastic succession, only one dynasty could be considered orthodox at any given time.[66] Most modern sources consider the legitimate line of succession to be as follows:[66]

These historical legitimacy disputes are similar to the modern competing claims of legitimacy by the People's Republic of China based in Beijing and the Republic of China based in Taipei. Both regimes formally adhere to the One-China policy and claim to be the sole legitimate representative of the whole of China.[81]

Agnatic lineages

There were several groups of Chinese dynasties that were ruled by families with patrilineal relations, yet due to various reasons these regimes are considered to be separate dynasties and given distinct retroactive names for historiographical purpose. Such conditions as differences in their official dynastic title and fundamental changes having occurred to their rule would create the need for nomenclatural distinction, despite these dynasties sharing common ancestral origins.

Additionally, numerous other dynasties claimed descent from earlier dynasties as a calculated political move to obtain or enhance their legitimacy, even if such claims were unfounded.

The agnatic relations of the following groups of Chinese dynasties are typically recognized by historians:

- Western Zhou and Eastern Zhou

- The Western Zhou and the Eastern Zhou are collectively known as the Zhou dynasty[10][82]

- The founder of the Eastern Zhou, the King Ping of Zhou, was a son of the last Western Zhou ruler, the King You of Zhou

- Western Han, Eastern Han, Shu Han, and Liu Song

- The Western Han and the Eastern Han are collectively known as the Han dynasty[83]

- The first emperor of the Eastern Han, the Emperor Guangwu of Han, was a ninth-generation descendant of the Western Han founder, the Emperor Gao of Han; he was also a seventh-generation descendant of the sixth Western Han monarch, the Emperor Jing of Han

- The founder of the Shu Han, the Emperor Zhaolie of Shu Han, was also descended from the Emperor Jing of Han

- The Book of Song states that the first Liu Song ruler, the Emperor Wu of Liu Song, was a male-line descendant of a younger brother of the Emperor Gao of Han, the Prince Yuan of Chu

- Western Jin and Eastern Jin

- The Western Jin and the Eastern Jin are collectively known as the Jin dynasty[84]

- The Eastern Jin founder, the Emperor Yuan of Jin, was a great-grandson of the Western Jin progenitor, the Emperor Xuan of Jin; he was also a grandson of the Prince Wu of Langya and a son of the Prince Gong of Langya

- Han Zhao and Hu Xia

- The Han Zhao founder, the Emperor Guangwen of Han Zhao, and the Hu Xia founder, the Emperor Wulie of Hu Xia, were descended from Liu Qiangqu and Liu Qubei respectively; according to the History of the Northern Dynasties, Liu Qiangqu and Liu Qibei were brothers

- Former Yan, Later Yan, and Southern Yan

- The founder of the Later Yan, the Emperor Chengwu of Later Yan, was a son of the Former Yan founder, the Emperor Wenming of Former Yan

- The first monarch of the Southern Yan, the Emperor Xianwu of Southern Yan, was also a son of the Emperor Wenming of Former Yan

- Western Liang and Tang dynasty

- The founder of the Tang dynasty, the Emperor Gaozu of Tang, was a seventh-generation descendant of the Western Liang founder, the Prince Wuzhao of Western Liang

- Northern Wei, Eastern Wei, and Western Wei

- The only ruler of the Eastern Wei, the Emperor Xiaojing of Eastern Wei, was a great-grandson of the seventh emperor of the Northern Wei, the Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei

- The Western Wei founder, the Emperor Wen of Western Wei, was a grandson of the Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei

- Southern Qi and Liang dynasty

- The founder of the Liang dynasty, the Emperor Wu of Liang, was a son of the Emperor Wen of Liang who was a distant cousin of the Southern Qi founder, the Emperor Gao of Southern Qi

- Later Han and Northern Han

- The first ruler of the Northern Han, the Emperor Shizu of Northern Han, was a younger brother of the Later Han founder, the Emperor Gaozu of Later Han

- Liao dynasty and Western Liao

- The Western Liao founder, the Emperor Dezong of Western Liao, was an eighth-generation descendant of the first emperor of the Liao dynasty, the Emperor Taizu of Liao

- Northern Song and Southern Song

- The Northern Song and the Southern Song are collectively known as the Song dynasty[85]

- The first ruler of the Southern Song, the Emperor Gaozong of Song, was a son of the eighth Northern Song monarch, the Emperor Huizong of Song; he was also a younger brother of the last Northern Song emperor, the Emperor Qinzong of Song

- Yuan dynasty and Northern Yuan

- The Emperor Huizong of Yuan was both the last emperor of the Yuan dynasty and the first ruler of the Northern Yuan

- Ming dynasty and Southern Ming

- The Southern Ming founder, the Hongguang Emperor, was a grandson of the 14th emperor of the Ming dynasty, the Wanli Emperor

- Later Jin and Qing dynasty

- The Emperor Taizong of Qing was both the last Later Jin khan and the first emperor of the Qing dynasty

Classification

Central Plain dynasties

The Central Plain is a vast area on the lower reaches of the Yellow River which formed the cradle of Chinese civilization. "Central Plain dynasties" (中原王朝; Zhōngyuán wángcháo) refer to dynasties of China that had their capital cities situated within the Central Plain.[86] This term could refer to dynasties of both Han and non-Han ethnic origins.[86]

Unified dynasties

"Unified dynasties" (大一統王朝; dàyītǒng wángcháo) refer to dynasties of China, regardless of their ethnic origin, that achieved the unification of China proper. "China proper" is a region generally regarded as the traditional heartland of the Han people, and is not equivalent to the term "China". Imperial dynasties that had unified China proper may be known as the "Chinese Empire" or the "Empire of China" (中華帝國; Zhōnghuá Dìguó).[87][88]

The concept of "great unity" or "grand unification" (大一統; dàyītǒng) was first mentioned in the Chinese classical text Gongyang Commentary on the Spring and Autumn Annals that was supposedly authored by the Qi scholar Gongyang Gao.[89][90][91] Other prominent figures like Confucius and Mencius also touched upon this concept in their respective works.[92][93]

Historians typically consider the following dynasties to have unified China proper: the Qin dynasty, the Western Han, the Xin dynasty, the Eastern Han, the Western Jin, the Sui dynasty, the Tang dynasty, the Wu Zhou, the Northern Song, the Yuan dynasty, the Ming dynasty, and the Qing dynasty.[94][95] The status of the Northern Song as a unified dynasty is disputed among historians as the Sixteen Prefectures of Yan and Yun were partially administered by the contemporaneous Liao dynasty while the Western Xia exercised partial control over Hetao; the Northern Song, in this sense, did not truly achieve the unification of China proper.[94][96]

Conquest dynasties

"Conquest dynasties" (征服王朝; zhēngfú wángcháo) refer to dynasties of China founded by non-Han peoples that ruled parts or all of China proper.[97] This term was first coined by the historian and sinologist Karl August Wittfogel and remains a source of controversy among scholars who believe that Chinese history should be analyzed and understood from a multiethnic and multicultural perspective.[98] For instance, the Northern Wei and the Qing dynasty, established by the Xianbei and Manchu ethnicities respectively, are considered conquest dynasties of China.[97]

Naming convention

Official nomenclature

It was customary for Chinese monarchs to adopt an official name for the realm, known as the guóhào (國號; "name of the state"), upon the establishment of a dynasty.[99][100] During the rule of a dynasty, its guóhào functioned as the formal name of the state, both internally and for diplomatic purposes.

The formal name of Chinese dynasties was usually derived from one the following sources:

- The name of the ruling tribe or tribal confederation[101][102]

- e.g., the Xia dynasty took its name from its ruling class, the Xia tribal confederation[101]

- The noble title held by the dynastic founder prior to the founding of the dynasty[101][102]

- e.g., the Emperor Wu of Chen adopted the dynastic name "Chen" from his pre-imperial title "Prince of Chen" upon the establishment of the Chen dynasty[103]

- The name of a historical state that occupied the same geographical location as the new dynasty[102][104]

- e.g., the Former Yan was officially named "Yan" based on the ancient State of Yan located in the same region[104]

- The name of a previous dynasty from which the new dynasty claimed descent or succession from, even if such familial link was questionable[102]

- e.g., the Emperor Taizu of Later Zhou officially proclaimed the Later Zhou with the official title "Zhou" as he claimed ancestry from Guo Shu, a royal of the Zhou dynasty[105]

- A term with auspicious or other significant connotations[101][102]

- e.g., the Yuan dynasty was officially the "Great Yuan", a name derived from a clause in the Classic of Changes, "dà zāi Qián Yuán" (大哉乾元; "Great is the Heavenly and Primal")[106]

There were instances whereby the official name was changed during the reign of a dynasty. For example, the dynasty known retroactively as Southern Han initially used the name "Yue", only to be renamed to "Han" subsequently.[107]

The official title of several dynasties bore the character "dà" (大; "great"). In Yongzhuang Xiaopin by the Ming historian Zhu Guozhen, it was claimed that the first dynasty to do so was the Yuan dynasty.[108][109] However, several sources like the History of Liao and the History of Jin compiled by the Yuan historian Toqto'a revealed that the official dynastic name of some earlier dynasties such as the Liao and the Jin also contained the character "dà".[110][111] It was also common for officials, subjects, or tributary states of a particular dynasty to include the term "dà" (or an equivalent term in other languages) when referring to this dynasty as a form of respect, even if the official dynastic name did not include it.[109] For instance, The Chronicles of Japan referred to the Tang dynasty as "Ōkara" (大唐; "Great Tang") despite its dynastic name being simply "Tang".

While all dynasties of China sought to associate their respective realm with Zhōngguó (中國; "Central State"; usually translated as "Middle Kingdom" or "China" in English texts), none of these regimes officially used the term as their dynastic name.[112][113] Although the Qing dynasty explicitly identified their state with and employed "Zhōngguó"—and its Manchu equivalent "Dulimbai Gurun" (ᡩᡠᠯᡳᠮᠪᠠᡳ

ᡤᡠᡵᡠᠨ)—in official capacity in numerous international treaties beginning with the Treaty of Nerchinsk dated AD 1689, its dynastic name had remained the "Great Qing".[114][115] "Zhōngguó", which has become nearly synonymous with "China" in modern times, is a concept with geographical, political, and cultural connotations.[116]

The adoption of guóhào, as well as the importance assigned to it, had promulgated within the Sinosphere. Notably, rulers of Vietnam and Korea also declared guóhào for their respective realm.

Retroactive nomenclature

In Chinese historiography, historians generally do not refer to dynasties directly by their official name. Instead, historiographical names, which were most commonly derived from their official name, are used. For instance, the Sui dynasty is known as such because its formal name was "Sui". Likewise, the Jin dynasty was officially the "Great Jin".

When more than one dynasty shared the same Chinese character(s) as their formal name, as was common in Chinese history, prefixes are retroactively applied to dynastic names by historians in order to distinguish between these similarly-named regimes.[7][36][117] Frequently used prefixes include:

- Cardinal direction

- "Northern" (北; běi): e.g., Northern Qi, Northern Yuan

- "Southern" (南; nán): e.g., Southern Yan, Southern Tang

- "Eastern" (東; dōng): e.g., Eastern Jin, Eastern Wei

- "Western" (西; xī): e.g., Western Liang, Western Liao

- Sequence

- "Former"[lower-alpha 7] (前; qián): e.g., Former Qin, Former Shu

- "Later"[lower-alpha 8] (後; hòu): e.g., Later Zhao, Later Han

- Surname of the ruling family

- Other types of prefixes

A dynasty could be referred to by more than one retroactive name in Chinese historiography, albeit some are more widely used than others. For instance, the Western Han is also known as the "Former Han", and the Yang Wu is also called the "Southern Wu".[125][126]

Scholars usually make a historiographical distinction for dynasties whose rule were interrupted. For example, the Song dynasty is divided into the Northern Song and the Southern Song, with the Jingkang Incident as the dividing line; the original "Song" founded by the Emperor Taizu of Song was therefore differentiated from the "Song" restored under the Emperor Gaozong of Song.[127] In such cases, the regime had collapsed, only to be re-established; a nomenclatural distinction between the original regime and the new regime is thus necessary for historiographical purpose. Major exceptions to this historiographical practice include the Western Qin and the Tang dynasty, which were interrupted by the Later Qin and the Wu Zhou respectively.[128][129]

In Chinese sources, the term "dynasty" (朝; cháo) is usually omitted when referencing dynasties that have prefixes in their historiographical names. Such a practice is sometimes adopted in English usage, even though the inclusion of the word "dynasty" is also widely seen in English scholarly writings. For example, the Northern Zhou is also sometimes referred to as the "Northern Zhou dynasty".[130]

Often, scholars would refer to a specific Chinese dynasty by adding the word "China" after the dynastic name. For instance, "Tang China" refers to the Chinese state under the rule of the Tang dynasty and the corresponding historical era.[131]

Territorial extent

While the earliest Chinese dynasties were established along the Yellow River and the Yangtze River in China proper, numerous Chinese dynasties later expanded beyond the region to encompass other territorial domains.[132][133][134][135][136][137][138][139][140][141][142][143][144]

At various points in time, Chinese dynasties exercised control over China proper (including Hainan, Macau, and Hong Kong),[132][133][134] Taiwan,[135] Manchuria (both Inner Manchuria and Outer Manchuria),[136][137] Sakhalin,[138][139] Mongolia (both Inner Mongolia and Outer Mongolia),[137][140] Vietnam,[141][145] Tibet,[136][137] Xinjiang,[142] as well as parts of Central Asia,[137][138] the Korean Peninsula,[143] Afghanistan,[144][146] and Siberia.[137]

Territorially, the largest orthodox Chinese dynasty was either the Yuan dynasty or the Qing dynasty, depending on the historical source.[11][12][13][14][15][lower-alpha 3] This discrepancy can be mainly attributed to the ambiguous northern border of the Yuan realm: whereas some sources describe the Yuan border as located to the immediate north of the northern shore of Lake Baikal, others posit that the Yuan dynasty reached as far north as the Arctic coast.[147][148][149] In contrast, the borders of the Qing dynasty were demarcated and reinforced through a series of international treaties, and thus were more well-defined.

Apart from exerting direct control over the Chinese realm, various dynasties of China also maintained hegemony over other states and tribes through the Chinese tributary system.[150] The Chinese tributary system first emerged during the Western Han and lasted until the 19th century AD when the Sinocentric order broke down.[151][152]

The modern territorial claims of both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China are inherited from the lands once held by the Qing dynasty at the time of its collapse.[15][153][154][155][156]

List of major Chinese dynasties

This list includes only the major dynasties of China that are typically found in simplified forms of Chinese historical timelines. This list is neither comprehensive nor representative of Chinese history as a whole.

| Dynasty | Ruling house | Period of rule | Rulers | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name[lower-alpha 9] (English[lower-alpha 10] / Chinese[lower-alpha 11] / Hanyu Pinyin / Wade–Giles / Bopomofo) |

Origin of name | Surname (English[lower-alpha 10] / Chinese[lower-alpha 11]) |

Ethnicity[lower-alpha 12] | Status[lower-alpha 13] | Year | Term | Founder[lower-alpha 14] | Last monarch | List / Family tree | |

| Semi-legendary | ||||||||||

| Xia dynasty 夏朝 Xià Cháo Hsia4 Ch῾ao2 ㄒㄧㄚˋ ㄔㄠˊ |

Tribal name | Si[lower-alpha 15] 姒 |

Huaxia | Royal | 2070–1600 BC[161][lower-alpha 16][lower-alpha 17][lower-alpha 18] | 430 years[lower-alpha 17][lower-alpha 18] | Yu of Xia | Jie of Xia | (list) (tree) | |

| Ancient China | ||||||||||

| Shang dynasty 商朝 Shāng Cháo Shang1 Ch῾ao2 ㄕㄤ ㄔㄠˊ |

Toponym | Zi 子 |

Huaxia | Royal | 1600–1046 BC[165][lower-alpha 16][lower-alpha 19] | 554 years[lower-alpha 19] | Tang of Shang | Zhou of Shang | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Zhou[lower-alpha 20] 西周 Xī Zhōu Hsi1 Chou1 ㄒㄧ ㄓㄡ |

Toponym | Ji 姬 |

Huaxia | Royal | 1046–771 BC[167][lower-alpha 16][lower-alpha 21] | 275 years[lower-alpha 21] | Wu of Zhou | You of Zhou | (list) (tree) | |

| Eastern Zhou[lower-alpha 20] 東周 Dōng Zhōu Tung1 Chou1 ㄉㄨㄥ ㄓㄡ |

From Zhou dynasty | Ji 姬 |

Huaxia | Royal | 770–256 BC[167] | 514 years | Ping of Zhou | Nan of Zhou | (list) (tree) | |

| Early Imperial China[lower-alpha 22] | ||||||||||

| Qin dynasty 秦朝 Qín Cháo Ch῾in2 Ch῾ao2 ㄑㄧㄣˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

Toponym | Ying[lower-alpha 23] 嬴 |

Huaxia | Imperial (221–207 BC) Royal (207 BC) |

221–207 BC[169] | 14 years | Qin Shi Huang | Qin San Shi | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Han[lower-alpha 24] 西漢 Xī Hàn Hsi1 Han4 ㄒㄧ ㄏㄢˋ |

Toponym & Noble title | Liu 劉 |

Han | Imperial | 202 BC–AD 9[170][lower-alpha 25] | 211 years[lower-alpha 25] | Gao of Han | Liu Ying[lower-alpha 26] | (list) (tree) | |

| Xin dynasty 新朝 Xīn Cháo Hsin1 Ch῾ao2 ㄒㄧㄣ ㄔㄠˊ |

"New" | Wang 王 |

Han | Imperial | AD 9–23[173] | 14 years | Wang Mang | Wang Mang | (list) (tree) | |

| Eastern Han[lower-alpha 24] 東漢 Dōng Hàn Tung1 Han4 ㄉㄨㄥ ㄏㄢˋ |

From Han dynasty | Liu 劉 |

Han | Imperial | AD 25–220[174] | 195 years | Guangwu of Han | Xian of Han | (list) (tree) | |

| Three Kingdoms 三國 Sān Guó San1 Kuo2 ㄙㄢ ㄍㄨㄛˊ |

AD 220–280[175] | 60 years | (list) (tree) | |||||||

| Cao Wei 曹魏 Cáo Wèi Ts῾ao2 Wei4 ㄘㄠˊ ㄨㄟˋ |

Noble title | Cao 曹 |

Han | Imperial | AD 220–266[176] | 46 years | Wen of Cao Wei | Yuan of Cao Wei | (list) (tree) | |

| Shu Han 蜀漢 Shǔ Hàn Shu3 Han4 ㄕㄨˇ ㄏㄢˋ |

From Han dynasty | Liu 劉 |

Han | Imperial | AD 221–263[177] | 42 years | Zhaolie of Shu Han | Huai of Shu Han | (list) (tree) | |

| Eastern Wu 東吳 Dōng Wú Tung1 Wu2 ㄉㄨㄥ ㄨˊ |

Noble title | Sun 孫 |

Han | Royal (AD 222–229) Imperial (AD 229–280) |

AD 222–280[178] | 58 years | Da of Eastern Wu | Sun Hao | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Jin[lower-alpha 27][lower-alpha 28] 西晉 Xī Jìn Hsi1 Chin4 ㄒㄧ ㄐㄧㄣˋ |

Noble title | Sima 司馬 |

Han | Imperial | AD 266–316[179] | 50 years | Wu of Jin | Min of Jin | (list) (tree) | |

| Eastern Jin[lower-alpha 27][lower-alpha 28] 東晉 Dōng Jìn Tung1 Chin4 ㄉㄨㄥ ㄐㄧㄣˋ |

From Jin dynasty (AD 266–420) | Sima 司馬 |

Han | Imperial | AD 317–420[180] | 103 years | Yuan of Jin | Gong of Jin | (list) (tree) | |

| Sixteen Kingdoms[lower-alpha 29] 十六國 Shíliù Guó Shih2-liu4 Kuo2 ㄕˊ ㄌㄧㄡˋ ㄍㄨㄛˊ |

AD 304–439[182] | 135 years | (list) (tree) | |||||||

| Han Zhao 漢趙 Hàn Zhào Han4 Chao4 ㄏㄢˋ ㄓㄠˋ |

Toponym & From Han dynasty | Liu[lower-alpha 30] 劉 |

Xiongnu | Royal (AD 304–308) Imperial (AD 308–329) |

AD 304–329[185] | 25 years | Guangwen of Han Zhao | Liu Yao | (list) (tree) | |

| Cheng Han 成漢 Chéng Hàn Ch῾eng2 Han4 ㄔㄥˊ ㄏㄢˋ |

Toponym & From Han dynasty | Li 李 |

Di | Princely (AD 304–306) Imperial (AD 306–347) |

AD 304–347[186][lower-alpha 31] | 43 years[lower-alpha 31] | Wu of Cheng Han[lower-alpha 31] | Li Shi | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Zhao 後趙 Hòu Zhào Hou4 Chao4 ㄏㄡˋ ㄓㄠˋ |

Noble title | Shi 石 |

Jie | Royal (AD 319–330) Imperial (AD 330–351) Princely (AD 351) |

AD 319–351[188] | 32 years | Ming of Later Zhao | Shi Zhi | (list) (tree) | |

| Former Liang 前涼 Qián Liáng Ch῾ien2 Liang2 ㄑㄧㄢˊ ㄌㄧㄤˊ |

Toponym | Zhang 張 |

Han | Princely (AD 320–354, AD 355–363) Imperial (AD 354–355) Ducal (AD 363–376) |

AD 320–376[189] | 56 years | Cheng of Former Liang | Dao of Former Liang | (list) (tree) | |

| Former Yan 前燕 Qián Yān Ch῾ien2 Yen1 ㄑㄧㄢˊ ㄧㄢ |

Toponym | Murong 慕容 |

Xianbei | Princely (AD 337–353) Imperial (AD 353–370) |

AD 337–370[190] | 33 years | Wenming of Former Yan | You of Former Yan | (list) (tree) | |

| Former Qin 前秦 Qián Qín Ch῾ien2 Ch῾in2 ㄑㄧㄢˊ ㄑㄧㄣˊ |

Toponym | Fu[lower-alpha 32] 苻 |

Di | Imperial | AD 351–394[190][lower-alpha 33] | 43 years[lower-alpha 33] | Jingming of Former Qin[lower-alpha 33] | Fu Chong | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Yan 後燕 Hòu Yān Hou4 Yen1 ㄏㄡˋ ㄧㄢ |

From Former Yan | Murong[lower-alpha 34][lower-alpha 35] 慕容 |

Xianbei[lower-alpha 35] | Princely (AD 384–386) Imperial (AD 386–409) |

AD 384–409[195][lower-alpha 36] | 25 years[lower-alpha 36] | Chengwu of Later Yan | Zhaowen of Later Yan Huiyi of Yan[lower-alpha 37] |

(list) (tree) | |

| Later Qin 後秦 Hòu Qín Hou4 Ch῾in2 ㄏㄡˋ ㄑㄧㄣˊ |

Toponym | Yao 姚 |

Qiang | Royal (AD 384–386) Imperial (AD 386–417) |

AD 384–417[196] | 33 years | Wuzhao of Later Qin | Yao Hong | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Qin 西秦 Xī Qín Hsi1 Ch῾in2 ㄒㄧ ㄑㄧㄣˊ |

Toponym | Qifu 乞伏 |

Xianbei | Princely | AD 385–400, AD 409–431[197] | 37 years[lower-alpha 38] | Xuanlie of Western Qin | Qifu Mumo | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Liang[lower-alpha 39] 後涼 Hòu Liáng Hou4 Liang2 ㄏㄡˋ ㄌㄧㄤˊ |

Toponym | Lü 呂 |

Di | Ducal (AD 386–389) Princely (AD 389–396) Imperial (AD 396–403) |

AD 386–403[198] | 17 years | Yiwu of Later Liang | Lü Long | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern Liang 南涼 Nán Liáng Nan2 Liang2 ㄋㄢˊ ㄌㄧㄤˊ |

Toponym | Tufa 禿髮 |

Xianbei | Princely | AD 397–414[199] | 17 years | Wu of Southern Liang | Jing of Southern Liang | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern Liang 北涼 Běi Liáng Pei3 Liang2 ㄅㄟˇ ㄌㄧㄤˊ |

Toponym | Juqu[lower-alpha 40] 沮渠 |

Xiongnu[lower-alpha 40] | Ducal (AD 397–399, AD 401–412) Princely (AD 399–401, AD 412–439) |

AD 397–439[201] | 42 years | Duan Ye | Ai of Northern Liang | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern Yan 南燕 Nán Yān Nan2 Yen1 ㄋㄢˊ ㄧㄢ |

From Former Yan | Murong 慕容 |

Xianbei | Princely (AD 398–400) Imperial (AD 400–410) |

AD 398–410[202] | 12 years | Xianwu of Southern Yan | Murong Chao | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Liang 西涼 Xī Liáng Hsi1 Liang2 ㄒㄧ ㄌㄧㄤˊ |

Toponym | Li 李 |

Han | Ducal | AD 400–421[203] | 21 years | Wuzhao of Western Liang | Li Xun | (list) (tree) | |

| Hu Xia 胡夏 Hú Xià Hu2 Hsia4 ㄏㄨˊ ㄒㄧㄚˋ |

From Xia dynasty | Helian[lower-alpha 41] 赫連 |

Xiongnu | Imperial | AD 407–431[206] | 24 years | Wulie of Hu Xia | Helian Ding | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern Yan 北燕 Běi Yān Pei3 Yen1 ㄅㄟˇ ㄧㄢ |

From Former Yan | Feng[lower-alpha 42] 馮 |

Han[lower-alpha 42] | Imperial | AD 407–436[207][lower-alpha 43] | 29 years[lower-alpha 43] | Huiyi of Yan[lower-alpha 37] Wencheng of Northern Yan |

Zhaocheng of Northern Yan | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern dynasties 北朝 Běi Cháo Pei3 Ch῾ao2 ㄅㄟˇ ㄔㄠˊ |

AD 386–581[208] | 195 years | (list) (tree) | |||||||

| Northern Wei 北魏 Běi Wèi Pei3 Wei4 ㄅㄟˇ ㄨㄟˋ |

Toponym | Tuoba[lower-alpha 44] 拓跋 |

Xianbei | Princely (AD 386–399) Imperial (AD 399–535) |

AD 386–535[210] | 149 years | Daowu of Northern Wei | Xiaowu of Northern Wei | (list) (tree) | |

| Eastern Wei 東魏 Dōng Wèi Tung1 Wei4 ㄉㄨㄥ ㄨㄟˋ |

From Northern Wei | Yuan 元 |

Xianbei | Imperial | AD 534–550[211] | 16 years | Xiaojing of Eastern Wei | Xiaojing of Eastern Wei | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Wei 西魏 Xī Wèi Hsi1 Wei4 ㄒㄧ ㄨㄟˋ |

From Northern Wei | Yuan[lower-alpha 45] 元 |

Xianbei | Imperial | AD 535–557[211] | 22 years | Wen of Western Wei | Gong of Western Wei | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern Qi 北齊 Běi Qí Pei3 Ch῾i2 ㄅㄟˇ ㄑㄧˊ |

Noble title | Gao 高 |

Han | Imperial | AD 550–577[211] | 27 years | Wenxuan of Northern Qi | Gao Heng | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern Zhou 北周 Běi Zhōu Pei3 Chou1 ㄅㄟˇ ㄓㄡ |

Noble title | Yuwen 宇文 |

Xianbei | Imperial | AD 557–581[211] | 24 years | Xiaomin of Northern Zhou | Jing of Northern Zhou | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern dynasties 南朝 Nán Cháo Nan2 Ch῾ao2 ㄋㄢˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

AD 420–589[213] | 169 years | (list) (tree) | |||||||

| Liu Song 劉宋 Liú Sòng Liu2 Sung4 ㄌㄧㄡˊ ㄙㄨㄥˋ |

Noble title | Liu 劉 |

Han | Imperial | AD 420–479[214] | 59 years | Wu of Liu Song | Shun of Liu Song | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern Qi 南齊 Nán Qí Nan2 Ch῾i2 ㄋㄢˊ ㄑㄧˊ |

A prophecy on defeating the Liu clan | Xiao 蕭 |

Han | Imperial | AD 479–502[215] | 23 years | Gao of Southern Qi | He of Southern Qi | (list) (tree) | |

| Liang dynasty 梁朝 Liáng Cháo Liang2 Ch῾ao2 ㄌㄧㄤˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

Toponym | Xiao 蕭 |

Han | Imperial | AD 502–557[216] | 55 years | Wu of Liang | Jing of Liang | (list) (tree) | |

| Chen dynasty 陳朝 Chén Cháo Ch῾en2 Ch῾ao2 ㄔㄣˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

Noble title | Chen 陳 |

Han | Imperial | AD 557–589[217] | 32 years | Wu of Chen | Chen Shubao | (list) (tree) | |

| Middle Imperial China[lower-alpha 22] | ||||||||||

| Sui dynasty 隋朝 Suí Cháo Sui2 Ch῾ao2 ㄙㄨㄟˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

Noble title ("随" homophone) | Yang[lower-alpha 46] 楊 |

Han | Imperial | AD 581–619[219] | 38 years | Wen of Sui | Gong of Sui | (list) (tree) | |

| Tang dynasty 唐朝 Táng Cháo T῾ang2 Ch῾ao2 ㄊㄤˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

Noble title | Li[lower-alpha 47] 李 |

Han | Imperial | AD 618–690, AD 705–907[221] | 274 years[lower-alpha 48] | Gaozu of Tang | Ai of Tang | (list) (tree) | |

| Wu Zhou 武周 Wǔ Zhōu Wu3 Chou1 ㄨˇ ㄓㄡ |

From Zhou dynasty | Wu 武 |

Han | Imperial | AD 690–705[222] | 15 years | Wu Zhao | Wu Zhao | (list) (tree) | |

| Five Dynasties 五代 Wǔ Dài Wu3 Tai4 ㄨˇ ㄉㄞˋ |

AD 907–960[223] | 53 years | (list) (tree) | |||||||

| Later Liang[lower-alpha 39] 後梁 Hòu Liáng Hou4 Liang2 ㄏㄡˋ ㄌㄧㄤˊ |

Noble title | Zhu 朱 |

Han | Imperial | AD 907–923[224] | 16 years | Taizu of Later Liang | Zhu Youzhen | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Tang 後唐 Hòu Táng Hou4 T῾ang2 ㄏㄡˋ ㄊㄤˊ |

From Tang dynasty | Li[lower-alpha 49][lower-alpha 50][lower-alpha 51] 李 |

Shatuo[lower-alpha 51] | Imperial | AD 923–937[228] | 14 years | Zhuangzong of Later Tang | Li Congke | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Jin[lower-alpha 52] 後晉 Hòu Jìn Hou4 Chin4 ㄏㄡˋ ㄐㄧㄣˋ |

Toponym | Shi 石 |

Shatuo | Imperial | AD 936–947[229] | 11 years | Gaozu of Later Jin | Chu of Later Jin | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Han 後漢 Hòu Hàn Hou4 Han4 ㄏㄡˋ ㄏㄢˋ |

From Han dynasty | Liu 劉 |

Shatuo | Imperial | AD 947–951[229] | 4 years | Gaozu of Later Han | Yin of Later Han | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Zhou 後周 Hòu Zhōu Hou4 Chou1 ㄏㄡˋ ㄓㄡ |

From Zhou dynasty | Guo[lower-alpha 53] 郭 |

Han | Imperial | AD 951–960[229] | 9 years | Taizu of Later Zhou | Gong of Later Zhou | (list) (tree) | |

| Ten Kingdoms 十國 Shí Guó Shih2 Kuo2 ㄕˊ ㄍㄨㄛˊ |

AD 907–979[231] | 62 years | (list) (tree) | |||||||

| Former Shu 前蜀 Qián Shǔ Ch῾ien2 Shu3 ㄑㄧㄢˊ ㄕㄨˇ |

Toponym / Noble title | Wang 王 |

Han | Imperial | AD 907–925[232] | 18 years | Gaozu of Former Shu | Wang Yan | (list) (tree) | |

| Yang Wu 楊吳 Yáng Wú Yang2 Wu2 ㄧㄤˊ ㄨˊ |

Toponym | Yang 楊 |

Han | Princely (AD 907–919) Royal (AD 919–927) Imperial (AD 927–937) |

AD 907–937[233][lower-alpha 54] | 30 years[lower-alpha 54] | Liezu of Yang Wu[lower-alpha 54] | Rui of Yang Wu | (list) (tree) | |

| Ma Chu 馬楚 Mǎ Chǔ Ma3 Ch῾u3 ㄇㄚˇ ㄔㄨˇ |

Toponym | Ma 馬 |

Han | Royal (AD 907–930) Princely (AD 930–951) |

AD 907–951[235] | 44 years | Wumu of Ma Chu | Ma Xichong | (list) (tree) | |

| Wuyue 吳越 Wúyuè Wu2-yüeh4 ㄨˊ ㄩㄝˋ |

Toponym | Qian 錢 |

Han | Royal (AD 907–932, AD 937–978) Princely (AD 934–937) |

AD 907–978[235] | 71 years | Taizu of Wuyue | Zhongyi of Qin | (list) (tree) | |

| Min 閩 Mǐn Min3 ㄇㄧㄣˇ |

Toponym | Wang[lower-alpha 55] 王 |

Han | Princely (AD 909–933, AD 944–945) Imperial (AD 933–944, AD 945) |

AD 909–945[235] | 36 years | Taizu of Min | Tiande | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern Han 南漢 Nán Hàn Nan2 Han4 ㄋㄢˊ ㄏㄢˋ |

From Han dynasty | Liu 劉 |

Han | Imperial | AD 917–971[235] | 54 years | Gaozu of Southern Han | Liu Chang | (list) (tree) | |

| Jingnan 荊南 Jīngnán Ching1-nan2 ㄐㄧㄥ ㄋㄢˊ |

Toponym | Gao[lower-alpha 56] 高 |

Han | Princely | AD 924–963[235] | 39 years | Wuxin of Chu | Gao Jichong | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Shu 後蜀 Hòu Shǔ Hou4 Shu3 ㄏㄡˋ ㄕㄨˇ |

Toponym | Meng 孟 |

Han | Imperial | AD 934–965[235] | 31 years | Gaozu of Later Shu | Gongxiao of Chu | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern Tang 南唐 Nán Táng Nan2 T῾ang2 ㄋㄢˊ ㄊㄤˊ |

From Tang dynasty | Li[lower-alpha 57] 李 |

Han | Imperial (AD 937–958) Royal (AD 958–976) |

AD 937–976[239] | 37 years | Liezu of Southern Tang | Li Yu | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern Han 北漢 Běi Hàn Pei3 Han4 ㄅㄟˇ ㄏㄢˋ |

From Later Han | Liu[lower-alpha 58] 劉 |

Shatuo[lower-alpha 58] | Imperial | AD 951–979[241] | 28 years | Shizu of Northern Han | Yingwu of Northern Han | (list) (tree) | |

| Liao dynasty 遼朝 Liáo Cháo Liao2 Ch῾ao2 ㄌㄧㄠˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

"Iron" (Khitan homophone) / Toponym | Yelü 耶律 |

Khitan | Imperial | AD 916–1125[242][lower-alpha 59] | 209 years[lower-alpha 59] | Taizu of Liao | Tianzuo of Liao | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Liao 西遼 Xī Liáo Hsi1 Liao2 ㄒㄧ ㄌㄧㄠˊ |

From Liao dynasty | Yelü[lower-alpha 60] 耶律 |

Khitan[lower-alpha 60] | Royal (AD 1124–1132) Imperial (AD 1132–1218) |

AD 1124–1218[246][lower-alpha 61] | 94 years[lower-alpha 61] | Dezong of Western Liao | Kuchlug | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern Song[lower-alpha 62] 北宋 Běi Sòng Pei3 Sung4 ㄅㄟˇ ㄙㄨㄥˋ |

Toponym | Zhao 趙 |

Han | Imperial | AD 960–1127[248] | 167 years | Taizu of Song | Qinzong of Song | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern Song[lower-alpha 62] 南宋 Nán Sòng Nan2 Sung4 ㄋㄢˊ ㄙㄨㄥˋ |

From Song dynasty | Zhao 趙 |

Han | Imperial | AD 1127–1279[249] | 152 years | Gaozong of Song | Zhao Bing | (list) (tree) | |

| Western Xia 西夏 Xī Xià Hsi1 Hsia4 ㄒㄧ ㄒㄧㄚˋ |

Toponym | Weiming[lower-alpha 63] 嵬名 𗼨𗆟 |

Tangut | Imperial | AD 1038–1227[251] | 189 years | Jingzong of Western Xia | Li Xian | (list) (tree) | |

| Jin dynasty[lower-alpha 28] 金朝 Jīn Cháo Chin1 Ch῾ao2 ㄐㄧㄣ ㄔㄠˊ |

"Gold" | Wanyan 完顏 |

Jurchen | Imperial | AD 1115–1234[252] | 119 years | Taizu of Jin | Wanyan Chenglin | (list) (tree) | |

| Late Imperial China[lower-alpha 22] | ||||||||||

| Yuan dynasty 元朝 Yuán Cháo Yüan2 Ch῾ao2 ㄩㄢˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

"Great" / "Primacy" | Borjigin 孛兒只斤 ᠪᠣᠷᠵᠢᠭᠢᠨ |

Mongol | Imperial | AD 1271–1368[253][lower-alpha 64] | 97 years[lower-alpha 64] | Shizu of Yuan | Huizong of Yuan | (list) (tree) | |

| Northern Yuan 北元 Běi Yuán Pei3 Yüan2 ㄅㄟˇ ㄩㄢˊ |

From Yuan dynasty | Borjigin[lower-alpha 65] 孛兒只斤 ᠪᠣᠷᠵᠢᠭᠢᠨ |

Mongol[lower-alpha 65] | Imperial | AD 1368–1635[257][lower-alpha 66] | 267 years[lower-alpha 66] | Huizong of Yuan | Borjigin Ejei Khongghor[lower-alpha 66] | (list) (tree) | |

| Ming dynasty 明朝 Míng Cháo Ming2 Ch῾ao2 ㄇㄧㄥˊ ㄔㄠˊ |

"Bright" | Zhu 朱 |

Han | Imperial | AD 1368–1644[261] | 276 years | Hongwu | Chongzhen | (list) (tree) | |

| Southern Ming 南明 Nán Míng Nan2 Ming2 ㄋㄢˊ ㄇㄧㄥˊ |

From Ming dynasty | Zhu 朱 |

Han | Imperial | AD 1644–1662[262][lower-alpha 67] | 18 years[lower-alpha 67] | Hongguang | Yongli[lower-alpha 67] | (list) (tree) | |

| Later Jin[lower-alpha 52] 後金 Hòu Jīn Hou4 Chin1 ㄏㄡˋ ㄐㄧㄣ |

From Jin dynasty (AD 1115–1234) | Aisin Gioro 愛新覺羅 ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ ᡤᡳᠣᡵᠣ |

Jurchen[lower-alpha 68] | Royal | AD 1616–1636[266] | 20 years | Tianming | Taizong of Qing | (list) (tree) | |

Qing dynasty 清朝 Qīng Cháo Ch῾ing1 Ch῾ao2 ㄑㄧㄥ ㄔㄠˊ |

"Pure" | Aisin Gioro 愛新覺羅 ᠠᡳᠰᡳᠨ ᡤᡳᠣᡵᠣ |

Manchu | Imperial | AD 1636–1912[267][lower-alpha 69][lower-alpha 70] | 276 years | Taizong of Qing | Xuantong | (list) (tree) | |

This list includes only the major dynasties of China that are typically found in simplified forms of Chinese historical timelines. There were many other dynastic regimes that existed within or overlapped with the boundaries defined in the scope of Chinese historical geography.[lower-alpha 71] These were:[281]

- Dynastic fiefs that existed within the fengjian system: e.g., State of Deng, State of Huo, State of Chu, State of Yiqu

- Dynastic chiefdoms that existed within the jimi and tusi systems: e.g., Chiefdom of Bozhou, Chiefdom of Shuidong, Chiefdom of Yongning, Chiefdom of Tsanlha

- Localized dynastic regimes: e.g., Nanyue, Tuyuhun, Dali Kingdom, Kingdom of Tungning

- Short-lived dynastic regimes: e.g., Zhai Wei, Later Liao, Chen Han, Shun dynasty

- Regional dynastic regimes that ruled an area historically or currently associated with "China": e.g., Rouran Khaganate, Tibetan Empire, Bohai, Kara-Khanid Khanate

Dynasties that belonged to the following categories are excluded from this list:

- Dynasties outside of "China" with full or partial Chinese ancestry: e.g., Early Lý dynasty of Vietnam, Thonburi dynasty of Siam[282][283][284][285]

- Dynasties that ruled Chinese tributary states outside of "China": e.g., Đinh dynasty of Vietnam, First Shō dynasty of the Ryukyu Islands[286][287]

- Dynasties outside of "China" which claimed to be "Zhōngguó", "Zhōnghuá" (中華; "China"), or "Xiǎo Zhōnghuá" (小中華; "Little China"): e.g., Joseon dynasty of Korea, Nguyễn dynasty of Vietnam[288][289][290][291]

- Dynasties that ruled Sinicized states outside of "China": e.g., Baekje dynasty of Korea, Later Lê dynasty of Vietnam[292][293]

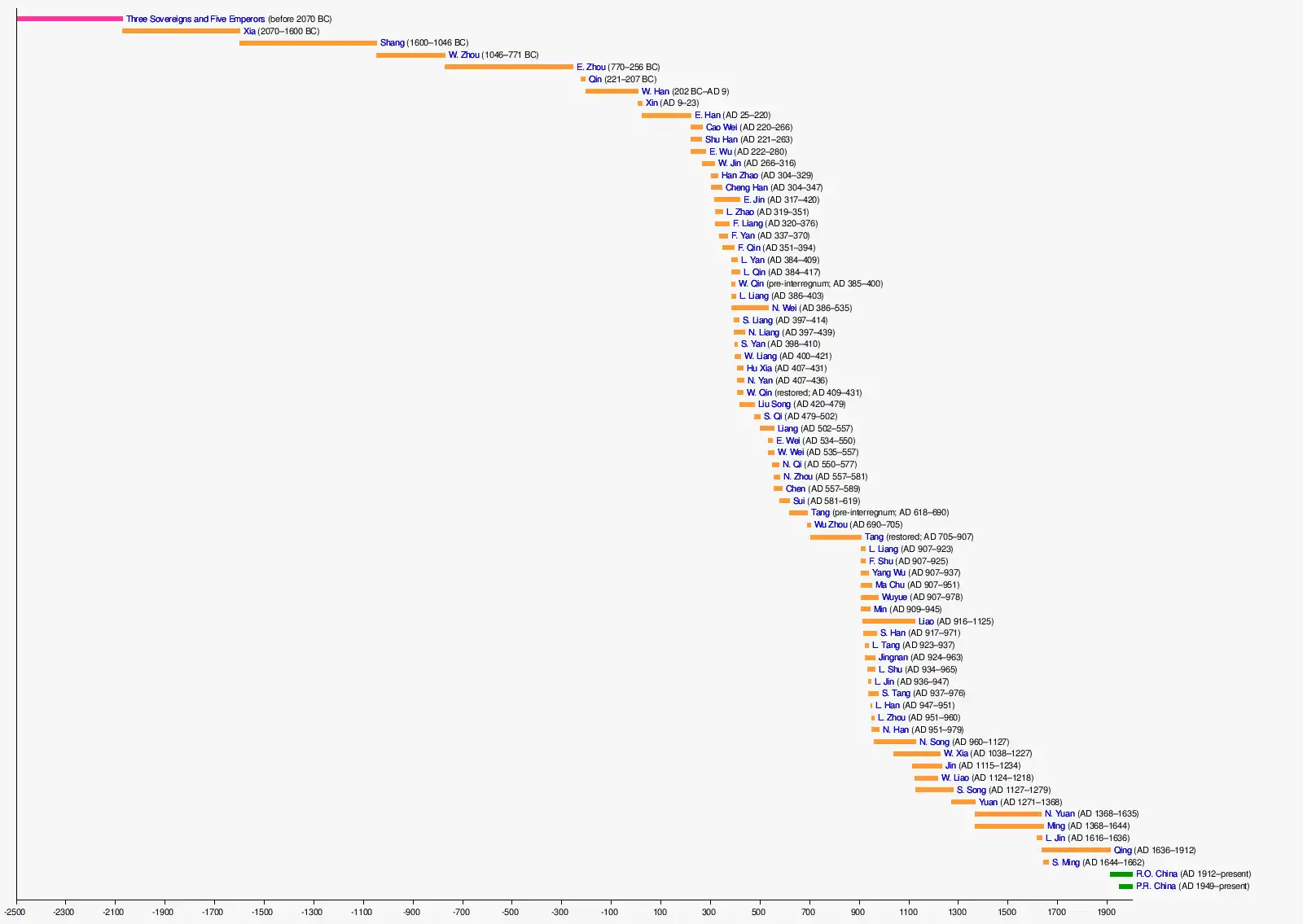

Timelines

Timeline of major historical periods

Timeline of major regimes

See also

- 1911 Revolution

- Ancient Chinese states

- Chinese historiography

- Chinese imperialism

- Chinese sovereign

- Conquest dynasty

- Dragon Throne

- Dynastic cycle

- East Asian cultural sphere

- Eighteen Kingdoms

- Emperor at home, king abroad

- Emperor of China

- Family tree of Chinese monarchs (ancient)

- Family tree of Chinese monarchs (early)

- Family tree of Chinese monarchs (late)

- Family tree of Chinese monarchs (middle)

- Family tree of Chinese monarchs (Warring States period)

- Fanzhen

- Fengjian

- Golden ages of China

- Head of the former Chinese imperial clan

- Head of the House of Aisin Gioro

- Historical capitals of China

- Jiedushi

- Jimi system

- List of Chinese monarchs

- List of Confucian states and dynasties

- List of recipients of tribute from China

- List of tributary states of China

- Mandate of Heaven

- Monarchy of China

- Names of China

- Pax Sinica

- Six Dynasties

- Three Sovereigns and Five Emperors

- Tianxia

- Timeline of Chinese history

- Tributary system of China

- Tusi

- Twenty-Four Histories

- Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project

- Zhonghua minzu

Notes

- While the Xia dynasty is typically considered to be the first Chinese dynasty, numerous historical sources like the Book of Documents mentioned two other dynasties that preceded the Xia: the "Tang" (唐) and the "Yu" (虞) dynasties.[1][2][3][4] The former is sometimes called the "Ancient Tang" (古唐) to distinguish it from other dynasties named "Tang".[5] If the historicity of these earlier dynasties were attested, Yu the Great would not have been the initiator of dynastic rule in China.

- All attempts at restoring monarchical and dynastic rule in China after the success of the Xinhai Revolution ended in failure. Hence, the abdication of the Xuantong Emperor in AD 1912 is typically regarded as the formal end of the Chinese monarchy.

- As per modern historiographical norm, the "Yuan dynasty" in this article refers exclusively to the realm based in China. However, the Chinese-style dynastic name "Great Yuan" (大元) as proclaimed by the Emperor Shizu of Yuan was meant to be applied to the entire Mongol Empire.[16][17][18] In spite of this, "Yuan dynasty" is rarely used in the broad sense of the definition by modern scholars due to the de facto disintegrated nature of the Mongol Empire.

- In AD 1906, the Qing dynasty initiated a series of reforms under the auspices of the Empress Xiaoqinxian to transition to a constitutional monarchy. On 27 August 1908, the Principles of the Constitution (欽定憲法大綱) was promulgated and served as an outline for a full constitution originally intended to take effect 10 years later.[25] On 3 November 1911, as a response to the ongoing Xinhai Revolution, the Qing dynasty issued the constitutional Nineteen Creeds (憲法重大信條十九條) which limited the power of the Qing emperor, marking the official transition to a constitutional monarchy.[26][27] The Qing dynasty, however, was overthrown on 12 February 1912.

- A powerful consort kin, usually a male, could force the reigning monarch to abdicate in his favor, thereby prompting a change in dynasty. For example, Wang Mang of the Xin dynasty was a nephew of the Empress Xiaoyuan who in turn was the spouse of the Western Han ruler, the Emperor Yuan of Han.[29]

- The term "kingdom" is potentially misleading as not all rulers held the title of king. For example, all sovereigns of the Cao Wei held the title huángdì (皇帝; "emperor") during their reign despite the realm being listed as one of the "Three Kingdoms". Similarly, monarchs of the Western Qin, one of the "Sixteen Kingdoms", bore the title wáng (王; usually translated as "prince" in English writings).

- "Anterior" is employed in some sources in place of "Former".[118][119]

- "Latter" or "Posterior" is employed in some sources in place of "Later".[120][121][122][123][124]

- The English and Chinese names stated are historiographical nomenclature. These should not be confused with the guóhào officially proclaimed by each dynasty. A dynasty may be known by more than one historiographical name.

- The English names shown are based on the Hanyu Pinyin renditions, the most common form of Mandarin romanization currently in adoption. Some scholarly works utilize the Wade–Giles system, which may differ drastically in the spelling of certain words. For instance, the Qing dynasty is rendered as "Ch῾ing dynasty" in Wade–Giles.[157]

- The Chinese characters shown are in Traditional Chinese. Some characters may have simplified versions that are currently used in mainland China. For instance, the characters for the Eastern Han are written as "東漢" in Traditional Chinese and "东汉" in Simplified Chinese.

- While Chinese historiography tends to treat dynasties as being of specific ethnic stocks, there were some monarchs who had mixed heritage.[158] For instance, the Jiaqing Emperor of the Manchu-led Qing dynasty was of mixed Manchu and Han descent, having derived his Han ancestry from his mother, the Empress Xiaoyichun.[159]

- The status of a dynasty was dependent upon the chief title bore by its monarch at any given time. For instance, since all monarchs of the Chen dynasty held the title of emperor during their reign, the Chen dynasty was of imperial status.

- The monarchs listed were the de facto founders of dynasties. However, it was common for Chinese monarchs to posthumously honor earlier members of the family as monarchs. For instance, while the Later Jin was officially established by the Emperor Gaozu of Later Jin, four earlier members of the ruling house were posthumously accorded imperial titles, the most senior of which was Shi Jing who was conferred the temple name "Jingzu" (靖祖) and the posthumous name "Emperor Xiao'an" (孝安皇帝).

- In addition to the ancestral name Si (姒), the ruling house of the Xia dynasty also bore the lineage name Xiahou (夏后).[160]

- The dates given for the Xia dynasty, the Shang dynasty, and the Western Zhou prior to the start of the Gonghe Regency in 841 BC are derived from the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project.

- The rule of the Xia dynasty was traditionally dated 2205–1766 BC as per the calculations made by the historian Liu Xin.[162][163] Accordingly, the Xia dynasty lasted 399 years excluding the 40-year interregnum between the reign of Xiang and Shao Kang.

- The Xia dynasty was interrupted by the rule of Yi and Han Zhuo for approximately 40 years.[164] Sources disagree on the dates of the start and end of the interregnum. Chinese historiography does not make a distinction between the realm that existed prior to the interregnum and the restored realm. Xiang was the last ruler before the interregnum; Shao Kang was the first ruler after the interregnum.[164]

- The rule of the Shang dynasty was traditionally dated 1766–1122 BC as per the calculations made by the historian Liu Xin.[162][166] Accordingly, the Shang dynasty lasted 644 years.

- The Western Zhou (西周) and the Eastern Zhou (東周) are collectively known as the Zhou dynasty (周朝; Zhōu Cháo; Chou1 Ch῾ao2; ㄓㄡ ㄔㄠˊ).[10][82]

- The rule of the Western Zhou was traditionally dated 1122–771 BC as per the calculations made by the historian Liu Xin.[162][166] Accordingly, the Western Zhou lasted 351 years.

- The terms "Chinese Empire" and "Empire of China" refer to the Chinese state under the rule of various imperial dynasties, particularly those that had unified China proper.[87][88]

- In addition to the ancestral name Ying (嬴), the ruling house of the Qin dynasty also bore the lineage name Zhao (趙).[168]

- The Western Han (西漢) and the Eastern Han (東漢) are collectively known as the Han dynasty (漢朝; Hàn Cháo; Han4 Ch῾ao2; ㄏㄢˋ ㄔㄠˊ).[83]

- Some historians consider 206 BC, the year in which the Emperor Gao of Han was proclaimed "King of Han", to be the start of the Western Han.[171] Accordingly, the Western Han lasted 215 years.

- Liu Ying was not officially enthroned and maintained the title huáng tàizǐ (皇太子; "crown prince") during the regency of Wang Mang.[172] The last Western Han monarch who was officially enthroned was the Emperor Ping of Han.

- The Western Jin (西晉) and the Eastern Jin (東晉) are collectively known as the Jin dynasty (晉朝; Jìn Cháo; Chin4 Ch῾ao2; ㄐㄧㄣˋ ㄔㄠˊ).[84]

- The names of the Jin dynasty (晉朝) of the Sima clan and the Jin dynasty (金朝) of the Wanyan clan are rendered similarly using the Hanyu Pinyin system, even though they do not share the same Chinese character for "Jin".

- The Sixteen Kingdoms are also referred to as the "Sixteen Kingdoms of the Five Barbarians" (五胡十六國; Wǔ Hú Shíliù Guó), although not all dynasties counted among the 16 were ruled by the "Five Barbarians".[181]

- The ruling house of the Han Zhao initially bore the surname Luandi (攣鞮).[183][184] Liu (劉) was subsequently adopted as the surname prior to the establishment of the Han Zhao.

- Some historians consider AD 303, the year in which the Emperor Jing of Cheng Han declared the era name "Jianchu" (建初), to be the start of the Cheng Han.[187] Accordingly, the Cheng Han was founded by the Emperor Jing of Cheng Han and lasted 44 years.

- The ruling house of the Former Qin initially bore the surname Pu (蒲).[191] The Emperor Huiwu of Former Qin subsequently adopted Fu (苻) as the surname in AD 349 prior to the establishment of the Former Qin.[191]

- Some historians consider AD 350, the year in which the Emperor Huiwu of Former Qin was proclaimed "Prince of Three Qins", to be the start of the Former Qin.[192] Accordingly, the Former Qin was founded by the Emperor Huiwu of Former Qin and lasted 44 years.

- As Lan Han, surnamed Lan (蘭), was not a member of the Murong (慕容) clan by birth, his enthronement was not a typical dynastic succession.[193]

- The Emperor Huiyi of Yan was of Goguryeo descent. Originally surnamed Gao (高), he was an adopted member of the Murong (慕容) clan.[194] His enthronement was therefore not a typical dynastic succession.

- Depending on the status of the Emperor Huiyi of Yan, the Later Yan ended in either AD 407 or AD 409 and lasted either 23 years or 25 years.

- The Emperor Huiyi of Yan could either be the last Later Yan monarch or the founder of the Northern Yan depending on the historian's characterization.[194]

- The Western Qin was interrupted by the Later Qin between AD 400 and AD 409. Chinese historiography does not make a distinction between the realm that existed up to AD 400 and the realm restored in AD 409. The Prince Wuyuan of Western Qin was both the last ruler before the interregnum and the first ruler after the interregnum.

- The names of the Later Liang (後涼) of the Lü clan and the Later Liang (後梁) of the Zhu clan are rendered similarly using the Hanyu Pinyin system, even though they do not share the same Chinese character for "Liang".

- Duan Ye, surnamed Duan (段), was of Han descent. The enthronement of the Prince Wuxuan of Northern Liang was therefore not a typical dynastic succession.[200]

- The ruling house of the Hu Xia initially bore the surname Luandi (攣鞮).[204] Liu (劉) was adopted as the surname prior to the establishment of the Hu Xia.[205] The Emperor Wulie of Hu Xia subsequently adopted Helian (赫連) as the surname in AD 413 after the establishment of the Hu Xia.[205]

- The Emperor Huiyi of Yan was of Goguryeo descent. Originally surnamed Gao (高), he was an adopted member of the Murong (慕容) clan.[194] The enthronement of the Emperor Wencheng of Northern Yan was therefore not a typical dynastic succession.

- Depending on the status of the Emperor Huiyi of Yan, the Northern Yan was established in either AD 407 or AD 409 and lasted either 29 years or 27 years.

- The ruling house of the Northern Wei initially bore the surname Tuoba (拓跋).[209] The Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei subsequently adopted Yuan (元) as the surname in AD 493 after the establishment of the Northern Wei.[209]

- The ruling house of the Western Wei initially bore the surname Tuoba (拓跋).[209] The Emperor Xiaowen of Northern Wei subsequently adopted Yuan (元) as the surname in AD 493 prior to the establishment of the Western Wei, only for the Emperor Gong of Western Wei to restore the surname Tuoba in AD 554 after the establishment of the Western Wei.[209][212]

- The ruling house of the Sui dynasty initially bore the surname Yang (楊). The Western Wei later bestowed the surname Puliuru (普六茹) upon the family.[218] The Emperor Wen of Sui subsequently restored Yang as the surname in AD 580 prior to the establishment of the Sui dynasty.

- The ruling house of the Tang dynasty initially bore the surname Li (李). The Western Wei later bestowed the surname Daye (大野) upon the family.[220] Li was subsequently restored as the surname in AD 580 prior to the establishment of the Tang dynasty.

- The Tang dynasty was interrupted by the Wu Zhou between AD 690 and AD 705. Chinese historiography does not make a distinction between the realm that existed up to AD 690 and the realm restored in AD 705. The Emperor Ruizong of Tang was the last ruler before the interregnum; the Emperor Zhongzong of Tang was the first ruler after the interregnum.

- The ruling house of the Later Tang initially bore the surname Zhuye (朱邪).[225] The Emperor Xianzu of Later Tang subsequently adopted Li (李) as the surname in AD 869 prior to the establishment of the Later Tang.[225]

- The Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang, originally without surname, was an adopted member of the Li (李) clan.[226] His enthronement was therefore not a typical dynastic succession.

- Li Congke was of Han descent. Originally surnamed Wang (王), he was an adopted member of the Li (李) clan.[227] His enthronement was therefore not a typical dynastic succession.

- The names of the Later Jin (後晉) of the Shi clan and the Later Jin (後金) of the Aisin Gioro clan are rendered similarly using the Hanyu Pinyin system, even though they do not share the same Chinese character for "Jin".

- The Emperor Shizong of Later Zhou, originally surnamed Chai (柴), was an adopted member of the Guo (郭) clan.[230] His enthronement was therefore not a typical dynastic succession.

- Some historians consider AD 902, the year in which the Emperor Taizu of Yang Wu was proclaimed "Prince of Wu", to be the start of the Yang Wu.[234] Accordingly, the Yang Wu was founded by the Emperor Taizu of Yang Wu and lasted 35 years.

- As Zhu Wenjin, surnamed Zhu (朱), was not a member of the Wang (王) clan by birth, his enthronement was not a typical dynastic succession.[236]

- The ruling house of the Jingnan initially bore the surname Gao (高). The Prince Wuxin of Chu subsequently adopted Zhu (朱) as the surname, only to restore the surname Gao prior to the establishment of the Jingnan.[237]

- The ruling house of the Southern Tang initially bore the surname Li (李). The Emperor Liezu of Southern Tang subsequently adopted Xu (徐) as the surname, only to restore the surname Li in AD 939 after the establishment of the Southern Tang.[238]

- The Emperor Yingwu of Northern Han was of Han descent. Originally surnamed He (何), he was an adopted member of the Liu (劉) clan.[240] His enthronement was therefore not a typical dynastic succession.

- Some historians consider AD 907, the year in which the Emperor Taizu of Liao was proclaimed "Khagan of the Khitans", to be the start of the Liao dynasty.[243] Accordingly, the Liao dynasty lasted 218 years.

- Kuchlug, originally without surname, was of Naiman descent. As he was not a member of the Yelü (耶律) clan by birth, his enthronement was not a typical dynastic succession.[244][245]

- Some historians consider AD 1132, the year in which the Emperor Dezong of Western Liao was proclaimed "Gurkhan", to be the start of the Western Liao.[247] Accordingly, the Western Liao lasted 86 years.

- The Northern Song (北宋) and the Southern Song (南宋) are collectively known as the Song dynasty (宋朝; Sòng Cháo; Sung4 Ch῾ao2; ㄙㄨㄥˋ ㄔㄠˊ).[85]

- The ruling house of the Western Xia initially bore the surname Tuoba (拓跋). The Tang dynasty and the Song dynasty later bestowed the surnames Li (李) and Zhao (趙) upon the family respectively. The Emperor Jingzong of Western Xia subsequently adopted Weiming (嵬名) as the surname in AD 1032 prior to the establishment of the Western Xia.[250]

- Some historians consider AD 1260, the year in which the Emperor Shizu of Yuan was proclaimed "Khagan of the Great Mongol State" and declared the era name "Zhongtong" (中統), to be the start of the Yuan dynasty.[254] Accordingly, the Yuan dynasty lasted 108 years.

- Choros Esen, surnamed Choros (綽羅斯), was of Oirat descent. As he was not a member of the Borjigin (孛兒只斤) clan by birth, his enthronement was not a typical dynastic succession.[255][256]

- Traditional Chinese historiography considers the Northern Yuan to have ended in either AD 1388 or AD 1402 when the dynastic name "Great Yuan" was abolished.[258][259] Accordingly, the Northern Yuan lasted either 20 years or 34 years, and its last ruler was either the Tianyuan Emperor or the Örüg Temür Khan. However, some historians regard the Mongol regime that existed from AD 1388 or AD 1402 up to AD 1635—referred to in the History of Ming as "Dada" (韃靼)—as a direct continuation of the Northern Yuan.[260]

- Some historians consider AD 1664, the year in which the reign of the Dingwu Emperor came to an end, to be the end of the Southern Ming.[263] Accordingly, the Southern Ming lasted 20 years and its last ruler was the Dingwu Emperor. However, the existence and identity of the Dingwu Emperor, supposedly reigned from AD 1646 to AD 1664, are disputed.

- The Jurchen ethnic group was renamed "Manchu" in AD 1635 by the Emperor Taizong of Qing.[264][265]

- The Articles of Favorable Treatment of the Great Qing Emperor After His Abdication (關於大清皇帝辭位之後優待之條件) allowed the Xuantong Emperor to retain his imperial title and enjoy other privileges following his abdication, resulting in the existence of a titular court in the Forbidden City known as the "Remnant Court of the Abdicated Qing Imperial Family" (遜清皇室小朝廷) between AD 1912 and AD 1924.[268] Feng Yuxiang revoked the privileges and abolished the titular court in AD 1924.[268]

- The Qing dynasty was briefly restored between 1 July 1917 and 12 July 1917 when Zhang Xun reinstalled the Xuantong Emperor to the Chinese throne.[54] Due to the abortive nature of the event, it is usually excluded from Qing history.

- As proposed by scholars such as Tan Qixiang, the geographical extent covered in the study of Chinese historical geography largely corresponds with the territories once ruled by the Qing dynasty during its territorial peak between the AD 1750s and the AD 1840s, prior to the outbreak of the First Opium War.[269] At its height, the Qing dynasty exercised jurisdiction over an area larger than 13 million km2, encompassing:[270][271][272]

- Tannu Uriankhai in the north;[273]

- Stanovoy Range and Sakhalin in the northeast;[274][275][276]

- Taiwan and its adjacent islands in the southeast;[274][275]

- Hainan and the South China Sea Islands in the south;[274][275][276][277]

- Pamir Mountains in the west;[275][276][278]

- Lake Balkhash in the northwest.[274][275][276][278]

- The dynastic regimes included in this timeline are the same as the list above.

References

Citations

- Nadeau, Randall (2012). The Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Chinese Religions. p. 31. ISBN 9781444361971.

- Yeo, Khiok-Khng (2008). Musing with Confucius and Paul: Toward a Chinese Christian Theology. p. 24. ISBN 9780227903308.

- Chao, Yuan-ling (2009). Medicine and Society in Late Imperial China: A Study of Physicians in Suzhou, 1600–1850. p. 73. ISBN 9781433103810.

- Wang, Shumin (2002). "夏、商、周之前还有个虞朝". Hebei Academic Journal. 22 (1): 146–147. Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- "古唐朝存在没?它是比虞朝夏朝更早的一个神秘王朝?". Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- Skutsch, Carl (2013). Encyclopedia of the World's Minorities. p. 287. ISBN 9781135193881.

- Keay, John (2010). China: A History. ISBN 9780007372089.

- Wang, Yeyang; Zhao, Qingyun (2016). 当代中国近代史理论研究. ISBN 9787516188231.

- Twitchett, Denis; Fairbank, John; Mote, Frederick (1978). The Cambridge History of China. pp. 394–395. ISBN 9780521243339.

- Sadow, Lauren; Peeters, Bert; Mullan, Kerry (2019). Studies in Ethnopragmatics, Cultural Semantics, and Intercultural Communication: Minimal English (and Beyond). p. 100. ISBN 9789813299795.

- Bauch, Martin; Schenk, Gerrit (2019). The Crisis of the 14th Century: Teleconnections between Environmental and Societal Change?. p. 153. ISBN 9783110660784.

- Ruan, Jiening; Zhang, Jie; Leung, Cynthia (2015). Chinese Language Education in the United States. p. 9. ISBN 9783319213088.

- Wei, Chao-hsin (1988). The General Themes of the Ocean Culture World. p. 17.

- Adler, Philip; Pouwels, Randall (2011). World Civilizations: Volume I: To 1700. p. 373. ISBN 9781133171065.

- Rowe, William (2010). China's Last Empire: The Great Qing. p. 1. ISBN 9780674054554.

- Robinson, David (2019). In the Shadow of the Mongol Empire: Ming China and Eurasia. p. 50. ISBN 9781108482448.

- Robinson, David (2009). Empire's Twilight: Northeast Asia Under the Mongols. p. 293. ISBN 9780674036086.

- Brook, Timothy; Walt van Praag, Michael van; Boltjes, Miek (2018). Sacred Mandates: Asian International Relations since Chinggis Khan. p. 45. ISBN 9780226562933.

- Nevus, John (1996). China and the Chinese. p. 22. ISBN 9788120606906.

- Wang, Hongsheng (2007). 历史的瀑布与峡谷:中华文明的文化结构和现代转型. p. 139. ISBN 9787300081830.

- "中国历代正统皇朝—天朝上国名称的起因来源". Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- "陆大鹏谈翻译:历史上的"王朝"与"皇朝"". Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Ebrey, Patricia; Liu, Kwang-Ching (2010). The Cambridge Illustrated History of China. p. 10. ISBN 9780521124331.

- Chan, Joseph (2013). Confucian Perfectionism: A Political Philosophy for Modern Times. p. 213. ISBN 9781400848690.

- Koenig, Lion; Chaudhuri, Bidisha (2017). Politics of the 'Other' in India and China: Western Concepts in Non-Western Contexts. p. 157. ISBN 9781317530558.

- Gao, Quanxi; Zhang, Wei; Tian, Feilong (2015). The Road to the Rule of Law in Modern China. p. 135. ISBN 9783662456378.

- To, Michael (2017). China's Quest for a Modern Constitutional Polity: from dynastic empires to modern republics. p. 54.

- Whitaker, Donald; Shinn, Rinn-Sup (1972). Area Handbook for the People's Republic of China. p. 37.

- Xiong, Deshan (2015). Social History Of China. p. 95. ISBN 9781938368264.

- Qi, Zhixiang (2016). 中國現當代人學史:思想演變的時代特徵及其歷史軌跡. p. 21. ISBN 9789869244923.

- Perdue, Peter (2009). China Marches West: The Qing Conquest of Central Eurasia. p. 6. ISBN 9780674042025.

- Elleman, Bruce; Paine, Sarah (2019). Modern China: Continuity and Change, 1644 to the Present. p. 19. ISBN 9781538103876.

- Zheng, Yongnian; Huang, Yanjie (2018). Market in State: The Political Economy of Domination in China. p. 83. ISBN 9781108473446.

- "我国古代改朝换代的方式不外乎两种,哪种才是主流?". Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Fan, Shuzhi (2007). 国史精讲. p. 99. ISBN 9787309055634.

- Wilkinson, Endymion (2000). Chinese History: A Manual. p. 14. ISBN 9780674002494.

- Perkins, Dorothy (2013). Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. p. 1. ISBN 9781135935627.

- Di Cosmo, Nicola (2007). The Diary of a Manchu Soldier in Seventeenth-Century China: "My Service in the Army", by Dzengseo. p. 1. ISBN 9781135789558.

- Elman, Benjamin (2006). A Cultural History of Modern Science in China. p. 46. ISBN 9780674023062.

- Tanner, Harold (2009). China: A History. p. 335. ISBN 978-0872209152.

- Pines, Yuri (2012). The Everlasting Empire: The Political Culture of Ancient China and Its Imperial Legacy. p. 157. ISBN 978-0691134956.

- Mote, Frederick (2003). Imperial China 900-1800. p. 798. ISBN 9780674012127.

- Skaff, Jonathan (2012). Sui-Tang China and Its Turko-Mongol Neighbors: Culture, Power, and Connections, 580-800. p. 80. ISBN 9780199734139.

- "封二王三恪昭示正统,周朝首创历代延续,明清却不敢采用". Retrieved 30 August 2020.

- Gong, Yin (2006). 中国民族政策史. p. 253.

- Zhang, Cheng (2007). 禅让:中国历史上的一种权力游戏. p. 200. ISBN 9787801066961.

- Stunkel, Kenneth (2012). Fifty Key Works of History and Historiography. p. 143. ISBN 9781136723667.

- Horner, Charles (2010). Rising China and Its Postmodern Fate: Memories of Empire in a New Global Context. p. 59. ISBN 9780820335889.

- Moody, Alys; Ross, Stephen (2020). Global Modernists on Modernism: An Anthology. p. 282. ISBN 9781474242349.

- Grosse, Christine (2019). The Global Manager's Guide to Cultural Literacy. p. 71. ISBN 9781527533875.

- Rošker, Jana; Suhadolnik, Nataša (2014). Modernisation of Chinese Culture: Continuity and Change. p. 74. ISBN 9781443867726.

- Aldrich, M. A. (2008). The Search for a Vanishing Beijing: A Guide to China's Capital Through the Ages. p. 176. ISBN 9789622097773.

- Schillinger, Nicholas (2016). The Body and Military Masculinity in Late Qing and Early Republican China: The Art of Governing Soldiers. p. 176. ISBN 9781498531696.

- Hao, Shiyuan (2019). China's Solution to Its Ethno-national Issues. p. 51. ISBN 9789813295193.

- Wells, Anne (2009). The A to Z of World War II: The War Against Japan. p. 167. ISBN 9780810870260.

- Wu, Bin (2019). Government Performance Management in China: Theory and Practice. pp. 44–45. ISBN 9789811382253.

- "历史上的国和代到底有什么区别?". Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Besio, Kimberly (2012). Three Kingdoms and Chinese Culture. p. 64. ISBN 9780791480496.

- Baaquie, Belal Ehsan; Wang, Qing-Hai (2018). "Chinese Dynasties and Modern China: Unification and Fragmentation". China and the World: Ancient and Modern Silk Road. 1 (1): 5. doi:10.1142/S2591729318500037.

- Nosco, Peter (1997). Confucianism and Tokugawa Culture. p. 68. ISBN 9780824818654.

- Holcombe, Charles (2017). A History of East Asia. pp. 62–63. ISBN 9781107118737.

- Yang, Shao-yun (2019). The Way of the Barbarians: Redrawing Ethnic Boundaries in Tang and Song China. p. 63. ISBN 9780295746012.

- Chen, Huaiyu (2007). The Revival of Buddhist Monasticism in Medieval China. p. 24. ISBN 9780820486246.

- Wakeman, Frederic (1985). The Great Enterprise: The Manchu Reconstruction of Imperial Order in Seventeenth-century China, Volume 1. p. 446. ISBN 9780520048041.

- Liu, Pujiang (2017). 正统与华夷:中国传统政治文化研究. ISBN 9787101125795.

- Lee, Thomas (2000). Education in Traditional China: A History. p. 238. ISBN 9004103635.

- Ng, On Cho; Wang, Edward (2005). Mirroring the Past: The Writing And Use of History in Imperial China. p. 177. ISBN 9780824829131.

- "宋和辽究竟哪个才是正统王朝?". Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Brook, Walt van Praag & Boltjes (2018). p. 52.

- Biran, Michal (2005). The Empire of the Qara Khitai in Eurasian History: Between China and the Islamic World. p. 93. ISBN 9780521842266.