Karrimor

Karrimor is a British brand of backpacks, outdoor and sports equipment, and clothing.

The company was founded as the Karrimor Bag Company in 1946.

Financial difficulties beginning in the late 1990s led to the company entering receivership in March 2003, after which the trademark was acquired by Sports Direct and is now used for various budget outdoor and running products.

History

Early history

Karrimor was founded and based in Lancashire, England, following World War II, with the company moving early on from Rawtenstall shop premises to nearby Clayton-le-Moors. Its history began in 1943, when Waterfoot bicycle shop owner Charles Parsons (1910–?) went blind from an accident that had occurred in 1939.[1] Under war and post-war conditions, he was also unable to obtain saddlebag and pannier stock for sale, but was still able to buy local raw fabric.[2] His wife and her sister (Mary Parsons 1914–? and Grace Davies) began to make bicycle bags for his shop,[2] which the family also began to sell locally to other shops. This led to the Karrimor Bag Company being formed in 1946.[3] As a saddlebag manufacturer it competed with companies then in the same industry, such as Carradice and Dunlop.[4]

The company was incorporated and changed its name to Karrimor Weathertite Products (named for their Weathertite cycling bags) in April 1952, before diversifying into backpacks in 1958,[3] where during the 1960s and 1970s it made its reputation.

Growth and renown

Relationships with climbers on high altitude expeditions was one of the keys to both innovation and marketing in both Karrimor and Mountain Equipment. Sharing the common ground of climbing and outdoor sport helped to create common understandings and shared perceptions. This bridge between technical knowledge and sporting needs played a crucial role in ... establish[ing] a growing dominance of the rucksack market [...] [Karrimor's] early development involved combining old and new technologies, materials and skills with a far higher level of customer interaction than had been common in the cotton industry.

Karrimor were still small when their son[2] Mike Parsons (1942–) joined in 1960, and began to build the 6-employee[7] company into a renowned international outdoor equipment manufacturer. The company's growth arose from a number of factors.[6]:61–63

1. CEO being a dedicated end-user of the products, and a capable designer/innovator in his own right Mike Parsons' own personal "obsession" with outdoor pursuits, including mountain marathons, led him to be described in the 1990s as the company's "best tester and salesman".[2] For many iconic products Parsons was also the group's primary innovator and designer; the company's success was largely credited to the very close links created by Parson's involvement both in manufacturing and technical research as a manufacturer, and direct engagement with hardened end users, their requirements, and their experiences. A 2006 OutdoorMagic.com article credits Parsons as the "legendary" creator of many of Karrimor's best known products, including the Jaguar, Alpiniste, and Hot Ice backpacks, KSB (Karrimor Sports Boot) footwear, the Karrimat, and the Kimmlite series.[8] (Parson's sister Jennifer Longbottom (1945–) also joined in 1972 within manufacturing.[9]) 2. Lancashire's location and local history relating to the industrial revolution and the textile industry A second (and third) fortuitous factor beyond a CEO who was himself an enthusiast, product user and innovator, lay in the firm's location and the Lancashire region's history. In the 19th century about 85% of all cotton manufactured worldwide had been processed in hundreds of Lancashire mill towns, close to the nearby major port of Liverpool.[10] Its legacy in the 1960s included an abundance locally of resources, businesses and expertise, allied with a strong traditional focus on product design – in particular for rubberised and coated rainwear – which was exceptionally well suited to the developing of new and improved outdoors textiles and products.[11]:10–15,23–24 Karrimor developed extremely close ties to these local resources, which was unusual at the time – product manager Eddie Creig stated in 1982:[12] "How can you expect to have the correct material if you don't speak to the people who know what coated fabric is? The resultant meetings always seemed to me the main reason why we have led the field in our section of the leisure industry."

3. Lancashire's location again, and its proximity to major outdoor activity regions Further related to location, the Lancashire region is also very close to some of the UK's most popular Hillwalking and climbing destinations such as the Lake District and Peak District. In the 1960s such activities gained more public popularity, causing an influx of dedicated hobbyists and a growth in popular demand and product expectations[11]:16–18,24 – in particular from nearby working class cities such as Manchester and Sheffield[6]:62–63 – and placing Karrimor in very close geographical proximity to its products' end-users. 4. Market timing and circumstances, and social dynamics within 1950s – 1960s Britain A fourth factor was market timing. Prosperity and consumer demand had returned to the UK in the 1950s,[13][14] and the company was well-positioned to benefit from a subsequent mass-public 'boom' in its field, and its shift[5]:32 from seasonal activity to year-round 'all weather' activity. This was driven in the first instance by post-war social change in the UK: the 1953 climbing of Everest and the resulting explosion of interest in climbing and climbing clubs; the 1950s creation of the Pennine Way and several National Parks in the UK; the creation of the motorway system and growth in leisure travel; pent-up post-war demand for outdoor activities and hobbies at all levels of society which was economically supported by high levels of employment; support for outdoor activities (and mountaineering in particular) at all levels of society causing these to feature prominently in the media, in education, and in youth activities; widespread familiarity with climbing and its equipment (from wartime service); and massive public interest in family camping and caravanning.[5]:8–15 There was also a lack of established high quality competition for the newly expanding sector, which was supplied by a combination of (largely French) imports and a flood of cheap, poor quality, army surplus stock.[5]:10–11 5. "Creative" use of social networking (uncommon at the time) to gain wide awareness, reach, and interest among end-users A final, and major, factor was the "creative" use of social networking,[5] which allowed Karrimor and its peers in the field to expand unusually quickly in these conditions. These manufacturers' owners had close personal links with many individuals involved in enthusiast organisations, publications, stores and outlets, public exhibitions, and expeditions, in their field, which were also often run by fellow climbers and enthusiasts.[5]:15–36 This ability to convert a new start-up into a widely known substantial business using social networking via fellow enthusiasts is commonplace in the internet era but was uncommon at the time; it significantly lowered barriers to entry and raised market reach and product feedback for those enthusiast-entrepreneurs able to create good quality products and gain positive coverage and discussion by their peers,[5][15] as well as access to highly regarded "lead users" who tested and collaborated in product design and real-world testing.[6]:65

For Karrimor, the buoyant market and its expansion, combined with an influx of hobbyists seeking equipment, local expertise, extensive networking, an existing established business, first-mover advantage, and a CEO who himself avidly engaged the hobbyist perspective on equipment and had considerable design skills, proved a fertile combination for the company's expansion.

Indeed, the 30-year period 1960 – 1990 has been described as a "golden age" for UK outdoor pursuit entrepreneurial companies generally.[16]

A major example of this synergistic combination of factors was Karrimor's innovation of the first robustly waterproof lightweight nylon texturised fabric, marketed as KS-100e.[17] Within 1960s textiles, cotton fibres expand when wet, bond to many coatings, and cotton fabrics are therefore easily made waterproof and rot-proof, but remain relatively heavy and cumbersome, and far from an ideal backpack textile, while nylon fabrics are lightweight, tough, flexible, easily cleaned, but technically very difficult to waterproof other than by adding coatings (with existing coatings such as polyurethane readily peeling or wearing away[6]:64), and when untreated are always permeable to water (its fibres don't expand to fill the gaps when wet). Therefore, in the 1960s, robustly waterproof fabrics were still largely based on rubberised coatings, duck-cotton and the like, even though these flexed poorly and added weight. In collaboration with a local company (either BM Coatings[9] or Gordon and Fairclough,[11]:13–14 sources differ), Karrimor developed an elastomer-nylon process in which toughened nylon fabric was waterproofed without significant weight or additional coatings, and without losing its natural flexibility, durability, texture, or other desirable qualities.[11]:13–15 The KSB footwear range was another example, combining lightweight fabric/suede uppers, new shock absorbent materials, and fellow Briton Ken Ledward's innovative sole, to create boots that were lightweight, tough, and shock absorbent.

Ground-breaking designs were also brought to market in diverse areas such as backpack design, camping mats, and other areas of equipment manufacture. Famous climbs such as Annapurna (1970)[11]:22–23 and Everest (1975 twice and 1978) using Karrimor equipment (covered in prestigious[5]:28[18] international mountaineering journals such as Ken Wilson's Mountain [19]) also had a lasting impact on the company's profile in its field, and gave its products a 'reputation for functionality and usability'.[11]:23 At times, this left manufacturing output "struggling to keep up with demand".[11]:23

In this way, between 1960 and 1990 the company innovated successfully and gained international recognition for many of its products (see 'pre-receivership recognition' below). Its first factory opened in 1965, in nearby Haslingden,[9] with two more following. The 1960s also saw business revenue grow 800% and the first exports.[9] In line with its growing global reputation and prominence, in 1975 the company changed name once more, to Karrimor International Ltd. By then, Karrimor was supplying an estimated 80% of the UK backpack market, and exporting some 40% of products.[17] (After the company's 2004 collapse, its assets were acquired by a new company, Karrimor Ltd, and as of 2013 trades under that name.[3])

Recession and resurgence

The early 1980s recession and pressure on manufacturing and exports were difficult, or even disastrous, for Karrimor, as for many other manufacturers and exporters in the UK. Two of the company's three factories closed and 100 of the 300-strong workforce were made redundant.[2] Determined to remain focused on the manufacturing strengths of the business, a core selling and reputation point, Parsons sustained the business by investing in product lines that would sell counter-seasonally to backpacks, and modernised Karrimor by visiting the United States to learn newer business practices, where manufacturing and business practices were often far in advance of those in the UK.[2] According to Parsons, the changes cost the family-owned business over £1 million by completion, but left Karrimor at the start of the 1990s as "the industry's most significant supplier",[2] and it continued to win awards and renown.

65-litre Karrimor 'Alpiniste' backpack from the early 1990s, featuring KS-100e fabric, twin compression straps and ice-axe loops, crampon straps on lid and Aergo M back design |

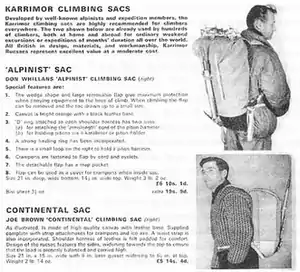

Early advert for Karrimor's Alpiniste and Joe Brown backpacks, circa 1960s. The Alpiniste "dominated" the 1960s in terms of climbing packs.[20] |

Pre-receivership achievements and recognition

Karrimor's pre-receivership highlights included the 'Alpiniste' backpack of the 1960s and purple 'Haston Alpiniste' pack of the 1970s – described as "dominating" the decade in terms of climbing packs – leading to Chris Bonington's team in their well-publicised 1975 ascent of Everest's south-west face using Karrimor equipment (Peter Habeler likewise used the same brand three years later for his oxygen-mask-free ascent, as did Junko Tabei, Everest's first female climber [9]); Ks-100e, a pioneering waterproof nylon-based fabric invented in 1973;[3][17] a British Design Award in 1991 for the Condor backpack; the design of the ubiquitous 'SA' backpack support system;[21] and pioneering development within lightweight fabric/suede footwear (the "footwear revolution" of the 1980s) with the KSB range.[20] Backpacks at that time were often made from heavy fabrics or with a solid external frame; the Alpiniste and its relatives were was the first 'modern' non-frame backpack, in the sense of being lightweight with the weight transferred to an integrated hip belt via a close-fit back support system. This was the forerunner of all non-frame modern packs of this kind.[3] During this period, Karrimor offered a lifetime warranty on its products, and was reputed for its in-house warranty and repairs service, often many years after the product purchase had taken place. These lifetime warranties are no longer honoured by the new owners of the Karrimor brand. Other highlights also included the introduction of closed cell foam mattresses (1965) known as the "Karrimat", and Karrimor's first exports and first experiments with nylon backpacks in 1967,[3] leading also to the first marketed waterproof nylon cycle bags in the 1970s (Karrimor later switched all its cycle bag production from cotton to nylon in 1980),[4] as well as the first mountain marathon (1968).[9]

For many years during the second half of the 20th century, Karrimor was a world-status innovator and brand in its field of outdoor equipment. Its range covered backpacks, clothing, hiking boots, and other camping, clothing and mountaineering equipment for outdoors activities. At the time of its 2004 receivership, OutdoorsMagic.com website described Karrimor as having a "tremendous tradition", a history that included "legendary" products, and a "very strong brand name",[22] Past owner Industrialinvest concurred, stating that the company had an "international reputation for outstanding [products]",[20] and in a 1996 review of top British manufacturers, The Independent described Karrimor as "a leader in its... field", albeit one that it felt had (like other businesses) "failed to invest and expand".[2]

The awards continued well into the 1990s. In 1991 Parsons and Karrimor received the Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild "Golden Boot" award for "outstanding contribution to the outdoors",[23] and in 1993 the company was one of 15 winners in the "Best UK factory" awards,[24] with Management Today describing Karrimor as a "world-renowned manufacturer" that had responded to the 1980s recession by investing heavily in automated production, U.S.-based stockflow processes, and production flexibility.[25]

In 1999, Cullinan's acquisition documents stated of Karrimor that it was:[26]

- "[O]ne of the leading European designers and distributors of technical rucksacks, outdoor clothing, footwear and related accessories. In its 52-year history, Karrimor has built its reputation for excellence on the back of innovative and ground breaking product development. Much of the research that went into this development was carried out on headline making expeditions. These include a host of Everest ascents, exploration of the world's deepest caves and lost wildernesses and, most recently, the "grand slam" trek to the north pole, south pole and the highest peak on each of five continents. Rucksack sales currently account for almost 30% of Karrimor's business and, thanks to their technological "halo", the company has been able to extend the brand into other categories of outdoor living such as tents, sleeping bags and technical outerwear. The clothing range extends from thermal base layers, fleece mid-layers and waterproof breathable outerwear to footwear and accessories ... Karrimor is one of the few outdoor brands that carries a full product line ... [and] enjoys international brand recognition among the outdoor enthusiasts and ... the most extensive retail distribution of any European outdoor company. Its products are sold in over 450 shops in the UK and exported to 22 countries."

Karrimor SF

Around 1995, Karrimor conceived, along with outside party Deric Gollop, a "special forces" range, Karrimor SF, which was launched as a separate company around 1998. It targeted police and military equipment needs. Being outside the Karrimor International group, the company was unaffected by Karrimor's later 2004 break-up and remains commercially active as of 2019 with its own products and production. Website: Karrimorsf.com

Financial distress and post-receivership new company history

During the late 1990s and 2000s, Karrimor's business grew but its financial robustness faltered as it took on investors and bought other companies. The UK was again in recession during 1990–1993, which was weathered without redundancies.[27] As the economy recovered and entered an extended boom, and the business continued to demonstrate its commercial strength, reputation and win yet further awards (see above),[23][24][25] the family sold the majority of the business in stages to outside investors (25% in 1993, and much of the remainder in 1996) to gain external investment, as the business sought to consolidate and expand its market position by growing through acquisition and increase its market presence in related areas such as retail and distributorships.

Acquisitions, Gartmore and 21 Invest

In 1993 the family sold 25% of the business to investment business Gartmore to fund expansion, via the acquisition of Phoenix Mountaineering and Life Cycle.[9][28] The strategy that did not work as hoped and by 1996 was placing the business into a "desperate" financial position.[29] Faced with financial losses,[28] a banking system that did not adequately support long term capital funding of the kind needed by the business,[29] and a need for funding to support investment,[30] a controlling majority stake[31] in the business was transferred[32] to investment group 21 Invest (now Investindustrial), the investing arm of the Italian Bonomi and Benetton empires,[31] for £7 million, with Mike Parsons becoming Karrimor's president.[31] Andrea Bonomi, the venture capital company's 31-year-old owner, had felt that Britain was "a fantastic place" for manufacturing, but under-appreciated by British people themselves, and considered Karrimor an exemplary family business (albeit in his view "mis-managed" [33]), owned by a "hardworking" family with a "fiercely loyal" workforce, and a good choice for UK investment.[34]

Under 21 Invest, Karrimor purchased Lowe Alpine's distributor Europa Sport, also acquiring Europa's existing distribution rights for other manufacturers.[9] The purchase was anticipated to boost Karrimor's group revenues, already £19 million, to a peak at around £30 million, and propel the company into second place in the UK footwear market and also consolidate its position within sports and leisure products.[9][35] However 21 Invest and Parsons found they strongly disagreed about the company's future plans, leading to "very severe" problems.[29] A 2001 article states of this period that: "[T]he venture capitalists attempt[ed] to turn its products into a fashion range, and in early 1998 Parsons was forced out. "We had very severe problems at the end. But there were no successors and we had already taken venture capital in, so once you've done that you're one step closer to selling the business anyway".[29] 21 Invest ultimately reported a substantial return on their investment, having focused on Karrimor's existing retail stores (initially branded 'Karrimor' and from 1999 Mountain Warehouse) and international sales,[33] before selling Karrimor's core business onward in 1999 to South African leisure group Cullinan Holdings;[9] 21 Invest also exited Mountain Warehouse three years later in 2002.[33]

Cullinan Holdings

Within a day of the 1999 sale completing, new owners Cullinan 'stunned' the company by announcing plans for cessation of existing manufacturing (immediate ending eighty jobs, or a quarter of the workforce)[36][37] and the intention to change Karrimor to a sales, marketing and distribution business.[38]

There was local fury, as the company and employees had been given assurances just one day earlier – prior to completion of sale – about their commitments to the business, to its workforce, and about future plans.[39] Cullinan did not comment on the matter.[39] The director of local Karrimor supplier Trubend Manufacturing also stepped in, to try and save the fleece garment product range and its 30 staff.[40]

In March 2003, the company bought YHA Outlets, a chain of fifteen outdoor products retail outlets.[41] The acquisition was not a success – partly due to misjudged price cutting at stores of products including Karrimor's own – and Karrimor were unable to recover. The falling sales, and Cullinan's 'unwillingness' to invest in the business (according to its receiver)[37] led to the company going into receivership in March 2004. At the time it had around 250 employees[42] and sales of around £18.7m.[43]

Within 24 hours, by 9 March 2004, its assets were bought out for £5 million by Lonsdale Sports, part of the Sports Direct group of companies,[42][43][44] who broke up the company, sold the outlets (both YHA and Karrimor's own), retaining mainly the rights to the brand name, which was licensed to such events as the long-standing Karrimor International Mountain Marathon (which later became the Original Mountain Marathon), and the company's intellectual property.

Post-receivership and Sports Direct

Following completion of the transaction, customer service activities such as lifetime warranties and repair services on previously sold goods were cancelled or outsourced. Manufacturing in the UK largely ended.

Some of Karrimor's previous management started a business under the name "Zero Degrees" which for a short time also produced outdoor equipment. Some warranty and repair workers remained active with Karrimor products at the associated company Lancashire Sports Repairs, which until around 2012 acted as Karrimor's warranty, repair, and after-sales service provider[45] and as of 2013 provides paid repair services of Karrimor equipment.

The Karrimor brand remains and is licensed and used for marketing and product branding purposes. Sports Direct continue to sell Karrimor branded products, which are as of 2013 largely made in China rather than the UK.

References

- Parson's accident is stated to have happened "8 years after" the 1931 founding of his Waterfoot shop (1939) and led to blindness "12 years later" (1943) – Bowen, David (18 August 1996). "British manufacturing: the best thing since sliced bread". The Independent. London. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- British manufacturing: the best thing since sliced bread – The Independent, 1996-08-18, David Bowen

- "Innovation Chronology – Gear Timezone". Innovation-for-extremes.net. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- The Carradice Story: "As British as the Union Jack" – Carradice saddlebags history, classiclightweights.co.uk, by Steve Griffith: "Carradice had a number of rivals in the cycle bag market. These included ... Dunlop ... and after WW2 Karrimor who originally were in nearby Rawtenstall. Karrimor branched out into walking and climbing equipment and were in the mid-1970s the first to market a nylon saddlebag [Cycletouring CTC Magazine April 1972 pp 90/91]. In the 1980s they [Karrimor] converted their entire range over to nylon."

- Parsons & Rose Communities of Knowledge: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Networks in the British Outdoor Trade 1960–1990 (2003)

- Path-dependent foundation of global design-driven outdoor trade in the northwest of England – Rose, Love & Parsons (1 December 2007), International Journal of Design, 1(3), pp.57–68

- This is sometimes quoted as "7 employees". The firm had 6 employees at the time, with Parsons himself being the 7th employee.

- Gear News: OMM 2007 Sneak Peek Archived 3 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine – 2006-07-14, by 'Jon'

- Karrimor detailed history and timeline, inov8.com.au Archived 10 March 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Gibb, Robert (2005). Greater Manchester: A panorama of people and places in Manchester and its surrounding towns. Myriad. p. 13. ISBN 1-904736-86-6.

- Cotton spinning to climbing gear: Practical aspects of design evolution in Lancashire and the North West of England – Rose, Love & Parsons, Lancaster University Management School Working Paper 2006/052.

- Eddie Creig, Karrimor product manager, Development of Ruc[k]sack Fabrics (1982), cited by Rose, Love, Parsons 2007[6]

- David Kynaston, Family Britain, 1951–1957 (2009)

- Peter Gurney, "The Battle of the Consumer in Postwar Britain," Journal of Modern History (2005) 77#4 pp. 956–987 in JSTOR

- Other UK outdoor pursuit manufacturers that gained market presence in a similar way, included Peter Storm (1954), Troll, Berghaus, Snowdon Mouldings, Henri Lloyd, and Mountain Equipment (1960s) – see table p.19, Parsons and Rose, 2003

- TGO, January 2001, p. 3 Cameron McNeish ‘ Go Outdoors – A Plea to Gear Manufacturers’, cited by Rose & Parsons Communities of Knowledge: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Networks in the British Outdoor Trade 1960–1990 (2003).

- "Outdoor Freedom: Karrimor history". Archived from the original on 5 August 2013. Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- GUEST EDITORIAL: Ken Wilson on the BMC Presidential Election – UKClimbing.com April 2009 (guest editor profile "Who is Ken Wilson?"): Once the world's most authoritative climbing periodical, Mountain magazine is still spoken of in hallowed tones today

- "Annapurna briefing – report on preparations and equipment for Annapurna south face" Mountain, 1969 – cited by Rose & Parsons Communities of Knowledge: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Networks in the British Outdoor Trade 1960–1990 (2003)].

- InvestIndustrial's description of its investment in Karrimor Archived 22 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Karrimor's 'about' pages

- "Karrimor Saved From Liquidation". OUTDOORSmagic. 22 February 2004. Archived from the original on 1 February 2014. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- OWG Golden Boot Award – Outdoor Writers and Photographers Guild website

- MANAGEMENT TODAY – BEST FACTORIES AWARDS 1993 – THE STAMP OF WORLD CLASS, Malcolm Wheatley, 1993-11-10

- Management Today: AWARDS 1993 – SMALL COMPANY COMMENDED – KARRIMOR, 1 November 1993

- Cullinan acquisition document, dated 1999-01-12

- 5 years ago: Staff on short time – Lancashire Telegraph 2 July 1996 describing Karrimor 5 years ago (1991)

- The uphill struggle for Karrimor – Acquisitions Monthly, pub. Thomson Financial 1996, ISSN 0952-3618, by Peter Luscombe.

- Keeping it in the family – The Engineer magazine, 12 April 2001 [some figures incorrect in source article and are struck out]: After

72years in the family, Karrimor ran into problems and brought in outside investors ... By 1996 Karrimor employed 320 people and had a turnover of £20m... "[W]e made two acquisitions that went wrong, and we were caught in a desperate situation. So we found some backers (21 Invest), and they continued with the company, but it didn't work satisfactorily" ... Parsons and 21 Invest disagreed over the future direction of the company, with the venture capitalists attempting to turn its products into a fashion range, and in early 1998 Parsons was forced out. "We had very severe problems at the end. But there were no successors and we had already taken venture capital in, so once you've done that you're one step closer to selling the business anyway". - Outdoor Gear Firm Karrimor to take partner – Lancashire Telegraph 2 October 1996

- Benetton take over Karrimor – Lancashire Telegraph 28 October 1996

- Acquisition Monthly (1996) describes this as "negotiating a funding package".

- InvestIndustrial statement on disposal of Mountain Warehouse (last part of Karrimor group) 16 August 2002 Archived 1 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Italy's young guns – The Independent, David Bowen, 3 November 1996

- Karrimor climbing higher – Lancashire Telegraph 12 August 1997]

- Review of the Year (January to March) 1999-12-27, Lancashire Telegraph: Fifty years of manufacturing at Karrimor's Clayton-le-Moors warehousing operation came to end with the news that its new South African owners was axing production and cutting around 80 jobs. Various sources state that Karrimor had ~320 (usually quoted as 300, 320[29] or 350) employees at the time, so eighty job losses would have been 25% of the 1996 workforce.

- Karrimor jobs go as firm is sold – Lancashire Telegraph 24 February 2004: [The receivers] said Karrimor had suffered from declining sales and its South African parent company was unwilling to make any further investment in the business, and also states: Karrimor was bought in 1999 by South African leisure group Cullinan Holdings which immediately cut manufacturing with the loss of 80 jobs.

- Karrimor jobs axe bombshell – Lancashire telegraph, 26 February 1999

- Last ditch bid to save jobs – Lancashire Telegraph 27 February 1999: The new owners have so far not issued any comment on the situation. Workers are still furious over the way the announcement was handled. "On the Wednesday the employees were told their jobs were safe and the day after they told them there would be job losses. We want to know how on earth that can happen," said one.

- Boss steps in to save jobs – Lancashire Telegraph 13 March 1999. The "Boss" in the article was Graham Lord of Trubend Manufacturing Ltd, via a short-lived separate company called The Fleece Factory Ltd (April 1999 – 2001): A businessman has stepped in to help save more than 30 jobs of axed staff at outdoor clothing firm Karrimor... Two weeks ago the company announced up to 80 job losses... after it decided to stop manufacturing to cut costs... Graham Lord, of Trubend Manufacturing, Bacup, a firm which already supplies Karrimor, has stepped in to keep production of the fleece garments in East Lancashire... Mr Lord is now looking for suitable premises for the new venture which will be a separate company to his existing firm. (See also company report on The Fleece Factory Ltd)

- Week, Retail (14 March 2003). "Karrimor makes early move for YHA outlets". Retail Week. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- "Karrimor sold within 24 hours of going into receivership – Bicycle Business". BikeBiz. 23 February 2004. Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- Soccer shop tycoon snaps up Karrimor – The Birmingham Post, 9 March 2004. (Full text, on thefreelibrary.com)

- Osborne, Alistair (3 March 2004). "Ashley slips Karrimor brand in his rucksack". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Shoe repair shop is a sole survivor – Lancashire Telegraph 2003-03-17, and Karrimor Ltd website Contact Us Archived 5 August 2013 at the Wayback Machine: Karrimor offer a repair and servicing for items no longer covered [emph. added] by our guarantee or requiring repair from accidental damage. This is a chargeable service and is operated on Karrimor's behalf by Karrimor's nominated and approved agent, Lancashire Sports Repairs www.lancashiresportsrepairs.co.uk (as at August 2013)

Further reading

- Invisible on Everest and related author commentary – 2003 book on the history of innovation in mountaineering equipment, co-authored by Karrimor founder Mike Parsons

- Creig, E., The development of rucksack fabrics – Climber and Rambler, pp. 49–50 (1980) and also paper presented at WIRA 1982 (Woollen Industries Research Association Conference) within 'Design for Survival' by Karrimor designer Eddie Creig.

- Parsons M. & Rose M.B., The neglected legacy of Lancashire cotton: Industrial clusters and the UK outdoor trade, 1960–1990 (2005), pub. Enterprise and Society, 6(4), 682–709.

External links

- Company specific

- Official site (and Karrimor SF official site)

- Various "History of Karrimor" articles –

- From Humble Beginnings (December 1996) – a 50th anniversary history of Karrimor, pub. Geographical (Campion Interactive Publishing);December 1996, Vol.68 issue 12, p10

- Parsons & Rose Communities of Knowledge: Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Networks in the British Outdoor Trade 1960–1990 (2003) – covers history of Karrimor to 1990 by former chairman Mike Parsons

- By Karrimor 'insiders': Innovation-forExtremes.net, Karrimor website 'About' page

- By third parties: OutdoorFreedom.co.za, inov8.com.au-Karrimor detailed history, inov8.com.au-The Evolution of outdoor gear

- 1975 coverage of Chris Bonnington's visit to Karrimor in preparation for his attempt the same year on Everest- pub. Textile Institute & Industry; March 1975, Vol.13 issue 3, p68

- Karrimor related news articles from the Lancashire Telegraph, 1995 onward – comprehensive online coverage of Karrimor

- Example page from Karrimor prior to 2004 receivership – showing highlights of product build/design at that time (Archive.org, August 2000)

- Gallery of historic Karrimor products and clippings on inov8.com.au