Languages of India

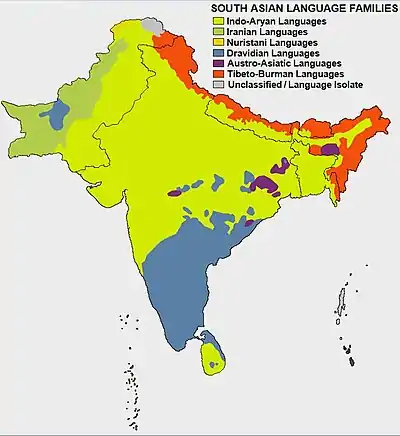

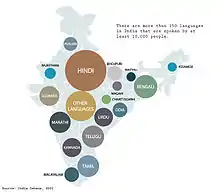

Languages spoken in India belong to several language families, the major ones being the Indo-Aryan languages spoken by 78.05% of Indians and the Dravidian languages spoken by 19.64% of Indians.[6][7] Languages spoken by the remaining 2.31% of the population belong to the Austroasiatic, Sino-Tibetan, Tai-Kadai and a few other minor language families and isolates.[8]:283 India has the world's fourth highest number of languages (427), after Nigeria (524), Indonesia (710) and Papua New Guinea (840).[9]

| Languages of India | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official | |

| Foreign | English – 200 million (L2 speakers 2003)[5] |

| Signed | |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of India |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Sport |

|

Article 343 of the Indian constitution stated that the official language of the Union is Hindi in Devanagari script instead of the extant English. Later, a constitutional amendment, The Official Languages Act, 1963, allowed for the continuation of English alongside Hindi in the Indian government indefinitely until legislation decides to change it.[2] The form of numerals to be used for the official purposes of the Union are "the international form of Indian numerals",[10][11] which are referred to as Arabic numerals in most English-speaking countries.[1] Despite the misconceptions, Hindi is not the national language of India; the Constitution of India does not give any language the status of national language.[12][13]

The Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution lists 22 languages,[14] which have been referred to as scheduled languages and given recognition, status and official encouragement. In addition, the Government of India has awarded the distinction of classical language to Kannada, Malayalam, Odia, Sanskrit, Tamil and Telugu. Classical language status is given to languages which have a rich heritage and independent nature.

According to the Census of India of 2001, India has 122 major languages and 1599 other languages. However, figures from other sources vary, primarily due to differences in definition of the terms "language" and "dialect". The 2001 Census recorded 30 languages which were spoken by more than a million native speakers and 122 which were spoken by more than 10,000 people.[15] Two contact languages have played an important role in the history of India: Persian[16] and English.[17] Persian was the court language during the Mughal period in India. It reigned as an administrative language for several centuries until the era of British colonisation.[18] English continues to be an important language in India. It is used in higher education and in some areas of the Indian government. Hindi, the most commonly spoken language in India today, serves as the lingua franca across much of North and Central India. Bengali is the second most spoken and understood language in the country with a significant amount of speakers in Eastern and North- eastern regions. Marathi is the third most spoken and understood language in the country with a significant amount of speakers in South-Western regions.[19] However, there have been concerns raised with Hindi being imposed in South India, most notably in the states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka.[20][21] Maharashtra, West Bengal, Assam, Punjab and other non-Hindi regions have also started to voice concerns about Hindi.[22]

History

The Southern Indian languages are from the Dravidian family. The Dravidian languages are indigenous to the Indian subcontinent.[23] Proto-Dravidian languages were spoken in India in the 4th millennium BCE and started disintegrating into various branches around 3rd millennium BCE.[24] The Dravidian languages are classified in four groups: North, Central (Kolami–Parji), South-Central (Telugu–Kui), and South Dravidian (Tamil-Kannada).[25]

The Northern Indian languages from the Indo-Aryan branch of the Indo-European family evolved from Old Indic by way of the Middle Indic Prakrit languages and Apabhraṃśa of the Middle Ages. The Indo-Aryan languages developed and emerged in three stages — Old Indo-Aryan (1500 BCE to 600 BCE), Middle Indo-Aryan stage (600 BCE and 1000 CE) and New Indo-Aryan (between 1000 CE and 1300 CE). The modern north Indian Indo-Aryan languages all evolved into distinct, recognisable languages in the New Indo-Aryan Age.[26]

Persian, or Farsi, was brought into India by the Ghaznavids and other Turko-Afghan dynasties as the court language. Culturally Persianized, they, in combination with the later Mughal dynasty (of Turco-Mongol origin), influenced the art, history and literature of the region for more than 500 years, resulting in the Persianisation of many Indian tongues, mainly lexically. In 1837, the British replaced Persian with English and Hindustani in Perso-Arabic script for administrative purposes and the Hindi movement of the 19th Century replaced Persianised vocabulary with Sanskrit derivations and replaced or supplemented the use of Perso-Arabic script for administrative purposes with Devanagari.[16][27]

Each of the northern Indian languages had different influences. For example, Hindustani was strongly influenced by Sanskrit, Arabic and Persian, leading to the emergence of Modern Standard Hindi and Modern Standard Urdu as registers of the Hindustani language. Bangla on the other hand has retained its Sanskritic roots while heavily expanding its vocabulary with words from Persian, English, French and other foreign languages.[28][29]

Inventories

The first official survey of language diversity in the Indian subcontinent was carried out by Sir George Abraham Grierson from 1898 to 1928. Titled the Linguistic Survey of India, it reported a total of 179 languages and 544 dialects.[30] However, the results were skewed due to ambiguities in distinguishing between "dialect" and "language",[30] use of untrained personnel and under-reporting of data from South India, as the former provinces of Burma and Madras, as well as the princely states of Cochin, Hyderabad, Mysore and Travancore were not included in the survey.[31]

Different sources give widely differing figures, primarily based on how the terms "language" and "dialect" are defined and grouped. Ethnologue, produced by the Christian evangelist organisation SIL International, lists 461 tongues for India (out of 6,912 worldwide), 447 of which are living, while 14 are extinct. The 447 living languages are further subclassified in Ethnologue as follows:[32][33]

- Institutional – 63

- Developing – 130

- Vigorous – 187

- In trouble – 54

- Dying – 13

The People's Linguistic Survey of India, a privately owned research institution in India, has recorded over 66 different scripts and more than 780 languages in India during its nationwide survey, which the organisation claims to be the biggest linguistic survey in India.[34]

The People of India (POI) project of Anthropological Survey of India reported 325 languages which are used for in-group communication by 5,633 Indian communities.[35]

Census of India figures

The Census of India records and publishes data with respect to the number of speakers for languages and dialects, but uses its own unique terminology, distinguishing between language and mother tongue. The mother tongues are grouped within each language. Many of the mother tongues so defined could be considered a language rather than a dialect by linguistic standards. This is especially so for many mother tongues with tens of millions of speakers that are officially grouped under the language Hindi.

Separate figures for Hindi, Urdu, and Punjabi were not issued, due to the fact the returns were intentionally recorded incorrectly in states such as East Punjab, Himachal Pradesh, Delhi, PEPSU, and Bilaspur.[36]

The 1961 census recognised 1,652 mother tongues spoken by 438,936,918 people, counting all declarations made by any individual at the time when the census was conducted.[37] However, the declaring individuals often mixed names of languages with those of dialects, subdialects and dialect clusters or even castes, professions, religions, localities, regions, countries and nationalities.[37] The list therefore includes languages with barely a few individual speakers as well as 530 unclassified mother tongues and more than 100 idioms that are non-native to India, including linguistically unspecific demonyms such as "African", "Canadian" or "Belgian".[37]

The 1991 census recognises 1,576 classified mother tongues.[38] According to the 1991 census, 22 languages had more than a million native speakers, 50 had more than 100,000 and 114 had more than 10,000 native speakers. The remaining accounted for a total of 566,000 native speakers (out of a total of 838 million Indians in 1991).[38][39]

As per the census of 2001, there are 1635 rationalised mother tongues, 234 identifiable mother tongues and 22 major languages.[15] Of these, 29 languages have more than a million native speakers, 60 have more than 100,000 and 122 have more than 10,000 native speakers.[40] There are a few languages like Kodava that do not have a script but have a group of native speakers in Coorg (Kodagu).[41]

According to the most recent census of 2011, after thorough linguistic scrutiny, edit and rationalization on 19,569 raw linguistic affiliation, the census recognizes 1369 rationalized mother tongues and 1474 names which were treated as ‘unclassified’ and relegated to ‘other’ mother tongue category.[42] Among, the 1369 rationalized mother tongues which are spoken by 10,000 or more speakers, are further grouped into appropriate set that resulted into total 121 languages. In these 121 languages, 22 are already part of the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India and other 99 are termed as "Total of other languages" which is one short as of the other languages recognized in 2001 census.[43]

Multilingualism

2011 Census India

| Language | First language speakers[44] |

First language speakers as a percentage of total population |

Second language speakers (millions) |

Third language speakers (millions) |

Total speakers (millions)[45] | Total speakers as a percentage of total population[46] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindi | 528,347,193 | 43.63 | 139 | 24 | 692 | 57.1 |

| English | 259,678 | 0.02 | 83 | 46 | 129 | 10.6 |

| Bengali | 97,237,669 | 8.30 | 9 | 1 | 107 | 8.9 |

| Marathi | 83,026,680 | 6.86 | 13 | 3 | 99 | 8.2 |

| Telugu | 81,127,740 | 6.70 | 12 | 1 | 95 | 7.8 |

| Tamil | 69,026,881 | 5.70 | 7 | 1 | 77 | 6.3 |

| Gujarati | 55,492,554 | 4.58 | 4 | 1 | 60 | 5.0 |

| Urdu | 50,772,631 | 4.19 | 11 | 1 | 63 | 5.2 |

| Kannada | 43,706,512 | 3.61 | 14 | 1 | 59 | 4.9 |

| Odia | 37,521,324 | 3.10 | 5 | 0.03 | 43 | 3.5 |

| Malayalam | 34,838,819 | 2.88 | 0.05 | 0.02 | 36 | 2.9 |

| Punjabi | 33,124,726 | 2.74 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 36 | 3.0 |

| Assamese | 15,311,351 | 1.26 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 24 | 2.0 |

| Maithili | 13,583,464 | 1.12 | 0.03 | 0.003 | 14 | 1.2 |

| Sanskrit | 24,821 | 0.00185 | 0.01 | 0.003 | 0.025 | 0.3 |

Ethnologue (2019, 22nd edition) worldwide

The following list consist of Indian subcontinent languages' total speakers worldwide in the 2019 edition of Ethnologue, a language reference published by SIL International, which is based in the United States.[47]

| Language | Total speakers (millions) |

|---|---|

| Hindi | 615 |

| Bengali | 265 |

| Urdu | 170 |

| Punjabi | 126 |

| Marathi | 95 |

| Telugu | 93 |

| Tamil | 81 |

| Gujarati | 61 |

| Kannada | 56 |

| Odia | 38 |

| Malayalam | 38 |

| Assamese | 15 |

| Santali | 7 |

| Sanskrit | 5 |

Language families

Ethnolinguistically, the languages of South Asia, echoing the complex history and geography of the region, form a complex patchwork of language families, language phyla and isolates.[8] Languages spoken in India belong to several language families, the major ones being the Indo-Aryan languages spoken by 78.05% of Indians and the Dravidian languages spoken by 19.64% of Indians. The languages of India belong to several language families, the most important of which are:[48][6][7][8][49]

| Rank | Language family | Population (2018) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Indo-Aryan language family | 1,045,000,000 (78.05%) |

| 2 | Dravidian language family | 265,000,000 (19.64%) |

| 3 | Austroasiatic language family | Unknown |

| 4 | Tibeto-Burman language family | Unknown |

| 5 | Tai–Kadai language family | Unknown |

| 6 | Great Andamanese languages | Unknown |

| Total | Languages of India | 1,340,000,000 |

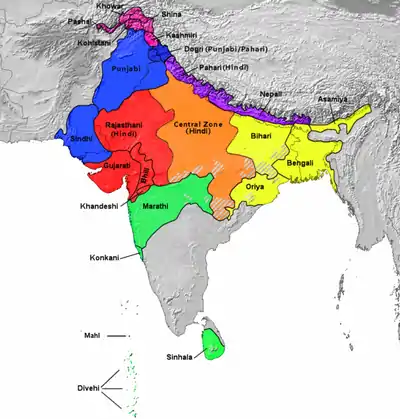

Indo-Aryan language family

The largest of the language families represented in India, in terms of speakers, is the Indo-Aryan language family, a branch of the Indo-Iranian family, itself the easternmost, extant subfamily of the Indo-European language family. This language family predominates, accounting for some 1035 million speakers, or over 76.5 of the population, as per 2018 estimate. The most widely spoken languages of this group are Hindi, Bengali, Marathi, Urdu, Gujarati, Punjabi, Kashmiri, Rajasthani, Sindhi, Assamese (Asamiya), Maithili and Odia.[50] Aside from the Indo-Aryan languages, other Indo-European languages are also spoken in India, the most prominent of which is English, as a lingua franca.

Dravidian language family

The second largest language family is the Dravidian language family, accounting for some 277 million speakers, or approximately 20.5% as per 2018 estimate The Dravidian languages are spoken mainly in southern India and parts of eastern and central India as well as in parts of northeastern Sri Lanka, Pakistan, Nepal and Bangladesh. The Dravidian languages with the most speakers are Telugu, Tamil, Kannada and Malayalam.[7] Besides the mainstream population, Dravidian languages are also spoken by small scheduled tribe communities, such as the Oraon and Gond tribes.[51] Only two Dravidian languages are exclusively spoken outside India, Brahui in Pakistan and Dhangar, a dialect of Kurukh, in Nepal.[52]

Austroasiatic language family

Families with smaller numbers of speakers are Austroasiatic and numerous small Sino-Tibetan languages, with some 10 and 6 million speakers, respectively, together 3% of the population.[53]

The Austroasiatic language family (austro meaning South) is the autochthonous language in Southeast Asia, arrived by migration. Austroasiatic languages of mainland India are the Khasi and Munda languages, including Santali. The languages of the Nicobar islands also form part of this language family. With the exceptions of Khasi and Santali, all Austroasiatic languages on Indian territory are endangered.[8]:456–457

Tibeto-Burman language family

The Tibeto-Burman language family are well represented in India. However, their interrelationships are not discernible, and the family has been described as "a patch of leaves on the forest floor" rather than with the conventional metaphor of a "family tree".[8]:283–5

Tibeto-Burman languages are spoken across the Himalayas in the regions of Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh, Nepal, Sikkim, Bhutan, Arunachal Pradesh, and also in the Indian states of West Bengal, Assam (hills and autonomous councils),[54][55][56] Meghalaya, Nagaland, Manipur, Tripura and Mizoram. Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in India include the scheduled languages Meitei and Bodo, the non-scheduled languages of Karbi, Lepcha, and many varieties of several related Tibetic, West Himalayish, Tani, Brahmaputran, Angami–Pochuri, Tangkhul, Zeme, Kukish language groups, amongst many others.

Tai-Kadai language family

Ahom language, a Southwestern Tai language, had been once the dominant language of the Ahom Kingdom in modern-day Assam, but was later replaced by the Assamese language (known as Kamrupi in ancient era which is the pre-form of the Kamrupi dialect of today). Nowadays, small Tai communities and their languages remain in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh together with Sino-Tibetans, e.g. Tai Phake, Tai Aiton and Tai Khamti, which are similar to the Shan language of Shan State, Myanmar; the Dai language of Yunnan, China; the Lao language of Laos; the Thai language of Thailand; and the Zhuang language in Guangxi, China.

Great Andamanese language family

The languages of the Andaman Islands form another group:[57]

- the Great Andamanese languages, comprising a number of extinct, and one highly endangered language

- the Ongan family of the southern Andaman Islands, comprising two extant languages, Önge and Jarawa, and one extinct language, Jangil.

In addition, Sentinelese is thought likely to be related to the above languages.[57]

Language isolates

The only language found in the Indian mainland that is considered a language isolate is Nihali.[8]:337 The status of Nihali is ambiguous, having been considered as a distinct Austroasiatic language, as a dialect of Korku and also as being a "thieves' argot" rather than a legitimate language.[58][59]

The other language isolates found in the rest of South Asia include Burushaski, a language spoken in Gilgit–Baltistan (administered by Pakistan), Kusunda (in western Nepal) and Vedda (in Sri Lanka).[8]:283 The validity of the Great Andamanese language group as a language family has been questioned and it has been considered a language isolate by some authorities.[8]:283[60][61]

In addition, a Bantu language, Sidi, was spoken until the mid-20th century in Gujarat by the Siddi.[8]:528

Official languages

.svg.png.webp)

Federal level

Prior to Independence, in British India, English was the sole language used for administrative purposes as well as for higher education purposes.[65]

In 1946, the issue of national language was a bitterly contested subject in the proceedings of the Constituent Assembly of India, specifically what should be the language in which the Constitution of India is written and the language spoken during the proceedings of Parliament and thus deserving of the epithet "national". Members belonging to the northern parts of India insisted that the Constitution be drafted in Hindi with the unofficial translation in English. This was not agreed to by the drafting Committee on the grounds that English was much better to craft the nuanced prose on constitutional subjects. The efforts to make Hindi the pre-eminent language were bitterly resisted by the members from those parts of India where Hindi was not spoken natively.

Eventually, a compromise was reached not to include any mention to a national language. Instead, Hindi in Devanagari script was declared to be the official language of the union, but for "fifteen years from the commencement of the Constitution, the English Language shall continue to be used for all the official purposes of the Union for which it was being used immediately before such commencement."[65]

Article 343 (1) of the Constitution of India states "The Official Language of the Union government shall be Hindi in Devanagari script."[66]:212[67] Unless Parliament decided otherwise, the use of English for official purposes was to cease 15 years after the constitution came into effect, i.e. on 26 January 1965.[66]:212[67]

As the date for changeover approached, however, there was much alarm in the non Hindi-speaking areas of India, especially in Kerala, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Punjab, West Bengal, Karnataka, Puducherry and Andhra Pradesh. Accordingly, Jawaharlal Nehru ensured the enactment of the Official Languages Act, 1963,[68][69] which provided that English "may" still be used with Hindi for official purposes, even after 1965.[65] The wording of the text proved unfortunate in that while Nehru understood that "may" meant shall, politicians championing the cause of Hindi thought it implied exactly the opposite.[65]

In the event, as 1965 approached, India's new Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri prepared to make Hindi paramount with effect from 26 January 1965. This led to widespread agitation, riots, self-immolations and suicides in Tamil Nadu. The split of Congress politicians from the South from their party stance, the resignation of two Union ministers from the South and the increasing threat to the country's unity forced Shastri to concede.[65][21]

As a result, the proposal was dropped,[70][71] and the Act itself was amended in 1967 to provide that the use of English would not be ended until a resolution to that effect was passed by the legislature of every state that had not adopted Hindi as its official language, and by each house of the Indian Parliament.[68]

The Constitution of India does not give any language the status of national language.[12][13]

Hindi

Hindi, written in Devanagari script, is the most prominent language spoken in the country. In the 2001 census, 422 million (422,048,642) people in India reported Hindi to be their native language.[72] This figure not only included Hindi speakers of Hindustani, but also people who identify as native speakers of related languages who consider their speech to be a dialect of Hindi, the Hindi belt. Hindi (or Hindustani) is the native language of most people living in Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Chhattisgarh, Himachal Pradesh, Chandigarh, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Haryana, and Rajasthan.[73]

"Modern Standard Hindi", a standardised language is one of the official languages of the Union of India. In addition, it is one of only two languages used for business in Parliament however the Rajya Sabha now allows all 22 official languages on the Eighth Schedule to be spoken.[74]

Hindustani, evolved from khari boli (खड़ी बोली), a prominent tongue of Mughal times, which itself evolved from Apabhraṃśa, an intermediary transition stage from Prakrit, from which the major North Indian Indo-Aryan languages have evolved.

Varieties of Hindi spoken in India include Rajasthani, Braj Bhasha, Haryanvi, Bundeli, Kannauji, Hindustani, Awadhi, Bagheli, Bhojpuri, Magahi, Nagpuri and Chhattisgarhi. By virtue of its being a lingua franca, Hindi has also developed regional dialects such as Bambaiya Hindi in Mumbai. In addition, a trade language, Andaman Creole Hindi has also developed in the Andaman Islands.[75]

In addition, by use in popular culture such as songs and films, Hindi also serves as a lingua franca across both North and Central India

Hindi is widely taught both as a primary language and language of instruction, and as a second tongue in most states.

English

British colonial legacy has resulted in English being a language for government, business and education. English, along with Hindi, is one of the two languages permitted in the Constitution of India for business in Parliament. Despite the fact that Hindi has official Government patronage and serves as a lingua franca over large parts of India, there was considerable opposition to the use of Hindi in the southern states of India, and English has emerged as a de facto lingua franca over much of India.[65][21] Journalist Manu Joseph, in a 2011 article in The New York Times, wrote that due to the prominence and usage of the language and the desire for English-language education, "English is the de facto national language of India. It is a bitter truth."[76]

Scheduled languages

Until the Twenty-first Amendment of the Constitution of India in 1967, the country recognised 14 official regional languages. The Eighth Schedule and the Seventy-First Amendment provided for the inclusion of Sindhi, Konkani, Meitei and Nepali, thereby increasing the number of official regional languages of India to 18. The Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India, as of 1 December 2007, lists 22 languages,[66]:330 which are given in the table below together with the regions where they are used.[72]

The individual states, the borders of most of which are or were drawn on socio-linguistic lines, can legislate their own official languages, depending on their linguistic demographics. The official languages chosen reflect the predominant as well as politically significant languages spoken in that state. Certain states having a linguistically defined territory may have only the predominant language in that state as its official language, examples being Karnataka and Gujarat, which have Kannada and Gujarati as their sole official language respectively. Telangana, with a sizeable Urdu-speaking Muslim population, has two languages, Telugu and Urdu, as its official languages.

Some states buck the trend by using minority languages as official languages. Jammu and Kashmir uses Urdu, which is spoken by fewer than 1% of the population. Meghalaya uses English spoken by 0.01% of the population. This phenomenon has turned majority languages into "minority languages" in a functional sense.[78]

- Lists of Official Languages of States and Union Territories of India

In addition to states and union territories, India has autonomous administrative regions which may be permitted to select their own official language – a case in point being the Bodoland Territorial Council in Assam which has declared the Bodo language as official for the region, in addition to Assamese and English already in use.[79] and Bengali in the Barak Valley,[80] as its official languages.

Prominent languages of India

Regional languages

In British India, English was the sole language used for administrative purposes as well as for higher education purposes. When India became independent in 1947, the Indian legislators had the challenge of choosing a language for official communication as well as for communication between different linguistic regions across India. The choices available were:

- Making "Hindi", which a plurality of the people (41%)[72] identified as their native language, the official language.

- Making English, as preferred by non-Hindi speakers, particularly Kannadigas and Tamils, and those from Mizoram and Nagaland, the official language. See also Anti-Hindi agitations.

- Declare both Hindi and English as official languages and each state is given freedom to choose the official language of the state.

The Indian constitution, in 1950, declared Hindi in Devanagari script to be the official language of the union.[66] Unless Parliament decided otherwise, the use of English for official purposes was to cease 15 years after the constitution came into effect, i.e. on 26 January 1965.[66] The prospect of the changeover, however, led to much alarm in the non Hindi-speaking areas of India, especially in South India whose native tongues are not related to Hindi. As a result, Parliament enacted the Official Languages Act in 1963,[81][82][83][84][85][86] which provided for the continued use of English for official purposes along with Hindi, even after 1965.

Bengali

Native to the Bengal region, comprising the nation of Bangladesh and the states of West Bengal, Tripura and Barak Valley region[87][88] of Assam. Bengali (also spelt as Bangla: বাংলা) is the sixth most spoken language in the world.[87][88] After the partition of India (1947), refugees from East Pakistan were settled in Tripura, and Jharkhand and the union territory of Andaman and Nicobar Islands. There is also a large number of Bengali-speaking people in Maharashtra and Gujarat where they work as artisans in jewellery industries. Bengali developed from Abahatta, a derivative of Apabhramsha, itself derived from Magadhi Prakrit. The modern Bengali vocabulary contains the vocabulary base from Magadhi Prakrit and Pali, also borrowings from Sanskrit and other major borrowings from Persian, Arabic, Austroasiatic languages and other languages in contact with.

Like most Indian languages, Bengali has a number of dialects. It exhibits diglossia, with the literary and standard form differing greatly from the colloquial speech of the regions that identify with the language.[89] Bengali language has developed a rich cultural base spanning art, music, literature and religion. Bengali has some of the oldest literature of all modern Indo-Aryan languages, dating from about 10th to 12th century ('Chargapada' buddhist songs). There have been many movements in defence of this language and in 1999 UNESCO declared 21 Feb as the International Mother Language Day in commemoration of the Bengali Language Movement in 1952.[90]

Marathi

Marathi is an Indo-Aryan language. It is the official language and co-official language in Maharashtra and Goa states of Western India respectively, and is one of the official languages of India. There were 83 million speakers of the language in 2011.[91] Marathi has the third largest number of native speakers in India and ranks 10th in the list of most spoken languages in the world. Marathi has some of the oldest literature of all modern Indo-Aryan languages; Oldest stone inscriptions from 8th century & literature dating from about 1100 AD (Mukundraj's Vivek Sindhu dates to the 12th century). The major dialects of Marathi are Standard Marathi and the Varhadi dialect. There are other related languages such as Khandeshi, Dangi, Vadvali, Samavedi. Malvani Konkani has been heavily influenced by Marathi varieties. Marathi is one of several languages that descend from Maharashtri Prakrit. Further change led to the Apabhraṃśa languages like Old Marathi.

Marathi Language Day (मराठी दिन/मराठी दिवस (transl. Marathi Dina/Marathi Diwasa) is celebrated on 27 February every year across the Indian states of Maharashtra and Goa. This day is regulated by the State Government. It is celebrated on the Birthday of eminent Marathi Poet Vi. Va. Shirwadkar, popularly known as Kusumagraj.

Marathi is the official language of Maharashtra and co-official language in the union territories of Daman and Diu and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. In Goa, Konkani is the sole official language; however, Marathi may also be used for all official purposes.

Over a period of many centuries the Marathi language and people came into contact with many other languages and dialects. The primary influence of Prakrit, Maharashtri, Apabhraṃśa and Sanskrit is understandable. Marathi has also influenced by the Austroasiatic, Dravidian and foreign languages such as Persian, Arabic. Marathi contains loanwords from Persian, Arabic, English and a little from French & Portuguese languages.

Telugu

Telugu is the most widely spoken Dravidian language in India and around the world. Telugu is an official language in Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Yanam, making it one of the few languages (along with Hindi, Bengali, and Urdu) with official status in more than one state. It is also spoken by a significant number of people in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Chhattisgarh, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and by the Sri Lankan Gypsy people. It is one of six languages with classical status in India. Telugu ranks fourth by the number of native speakers in India (81 million in the 2011 Census),[91] fifteenth in the Ethnologue list of most-spoken languages worldwide and is the most widely spoken Dravidian language.

Tamil

Tamil (also spelt as Thamizh: தமிழ்) is a Dravidian language predominantly spoken in Tamil Nadu, Puducherry and many parts of Sri Lanka. It is also spoken by large minorities in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Kerala, Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Malaysia, Singapore, Mauritius and throughout the world. Tamil ranks fifth by the number of native speakers in India (61 million in the 2001 Census[92]) and ranks 20th in the list of most spoken languages. It is one of the 22 scheduled languages of India and was the first Indian language to be declared a classical language by the Government of India in 2004. Tamil is one of the longest surviving classical languages in the world.[93][94] It has been described as "the only language of contemporary India which is recognisably continuous with a classical past".[95] The two earliest manuscripts from India,[96][97] acknowledged and registered by UNESCO Memory of the World register in 1997 and 2005, are in Tamil.[98] Tamil is an official language of Tamil Nadu, Puducherry, Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Sri Lanka and Singapore. It is also recognized as a minority language in Canada, Malaysia, Mauritius and South Africa.

Urdu

After independence, Modern Standard Urdu, the Persianised register of Hindustani became the national language of Pakistan. During British colonial times, a knowledge of Hindustani or Urdu was a must for officials. Hindustani was made the second language of British Indian Empire after English and considered as the language of administration. The British introduced the use of Roman script for Hindustani as well as other languages. Urdu had 70 million speakers in India (as per the Census of 2001), and, along with Hindi, is one of the 22 officially recognised regional languages of India and also an official language in the Indian states of Jammu and Kashmir, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Telangana that have significant Muslim populations.

Gujarati

Gujarati is an Indo-Aryan language. It is native to the west Indian region of Gujarat. Gujarati is part of the greater Indo-European language family. Gujarati is descended from Old Gujarati (c. 1100 – 1500 CE), the same source as that of Rajasthani. Gujarati is the chief language in the Indian state of Gujarat. It is also an official language in the union territories of Daman and Diu and Dadra and Nagar Haveli. According to the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), 4.5% of population of India (1.21 billion according to 2011 census) speaks Gujarati. This amounts to 54.6 million speakers in India.[99]

Kannada

Kannada language is a Dravidian language which branched off from Kannada-Tamil sub group around 500 B.C.E according to the Dravidian scholar Zvelebil.[100] According to the Dravidian scholars Steever and Krishnamurthy, the study of Kannada language is usually divided into three linguistic phases: Old (450–1200 CE), Middle (1200–1700 CE) and Modern (1700–present).[101][102] The earliest written records are from the 5th century,[103] and the earliest available literature in rich manuscript (Kavirajamarga) is from c. 850.[104][105] Kannada language has the second oldest written tradition of all languages of India.[106][107] Current estimates of the total number of epigraph present in Karnataka range from 25,000 by the scholar Sheldon Pollock to over 30,000 by the Sahitya Akademi,[108] making Karnataka state "one of the most densely inscribed pieces of real estate in the world".[109] According to Garg and Shipely, more than a thousand notable writers have contributed to the wealth of the language.[110][111]

Malayalam

Malayalam (/mæləˈjɑːləm/;[112] [ maləjaːɭəm]) has official language status in the state of Kerala and in the union territories of Lakshadweep and Puducherry. It belongs to the Dravidian family of languages and is spoken by some 38 million people. Malayalam is also spoken in the neighboring states of Tamil Nadu and Karnataka; with some speakers in the Nilgiris, Kanyakumari and Coimbatore districts of Tamil Nadu, and the Dakshina Kannada and the Kodagu district of Karnataka.[113][114][115] Malayalam originated from Middle Tamil (Sen-Tamil) in the 7th century.[116] As Malayalam began to freely borrow words as well as the rules of grammar from Sanskrit, the Grantha alphabet was adopted for writing and came to be known as Arya Eluttu.[117] This developed into the modern Malayalam script.[118]

Odia

Odia (formerly spelled Oriya)[119] is the only modern language officially recognized as a classical language from the Indo-Aryan group. Odia is primarily spoken in the Indian state of Odisha and has over 40 million speakers. It was declared as a classical language of India in 2014. Native speakers comprise 91.85% of the population in Odisha.[120][121] Odia originated from Odra Prakrit which developed from Magadhi Prakrit, a language spoken in eastern India over 2,500 years ago. The history of Odia language can be divided to Old Odia (3rd century BC −1200 century AD),[122] Early Middle Odia (1200–1400), Middle Odia (1400–1700), Late Middle Odia (1700–1870) and Modern Odia (1870 till present day). The National Manuscripts Mission of India have found around 213,000 unearthed and preserved manuscripts written in Odia.[123]

Punjabi

Punjabi, written in the Gurmukhi script in India, is one of the prominent languages of India with about 32 million speakers. In Pakistan it is spoken by over 80 million people and is written in the Shahmukhi alphabet. It is mainly spoken in Punjab but also in neighboring areas. It is an official language of Delhi and Punjab.

Assamese

Asamiya or Assamese language is most popular in the state of Assam.[124] It's an Eastern Indo-Aryan language having more than 15 million speakers as per world estimates by Encarta.[125]

Maithili

Maithili (/ˈmaɪtɪli/;[126] Maithilī) is an Indo-Aryan language native to India and Nepal. In India, it is widely spoken in the Bihar and Jharkhand states.[127][128] Native speakers are also found in other states and union territories of India, most notably in Uttar Pradesh and the National Capital Territory of Delhi.[129] In the 2011 census of India, It was reported by 1,35,83,464 people as their mother tongue comprising about 1.12% of the total population of India.[130] In Nepal, it is spoken in the eastern Terai, and is the second most prevalent language of Nepal.[131] Tirhuta was formerly the primary script for written Maithili. Less commonly, it was also written in the local variant of Kaithi.[132] Today it is written in the Devanagari script.[133]

In 2003, Maithili was included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constitution as a recognised regional language of India, which allows it to be used in education, government, and other official contexts.[134]

Classical languages of India

In 2004, the Government of India declared that languages that met certain requirements could be accorded the status of a "Classical Language" of India.[135] Over the next few years, several languages were granted the Classical status, and demands have been made for other languages, including Bengali[136][137] and Marathi.[138]

Languages thus far declared to be Classical:

- Tamil (in 2004),[139]

- Sanskrit (in 2005),[140]

- Kannada (in 2008),[141]

- Telugu (in 2008),[141]

- Malayalam (in 2013),[142]

- Odia (in 2014).[143][144]

In a 2006 press release, Minister of Tourism and Culture Ambika Soni told the Rajya Sabha the following criteria were laid down to determine the eligibility of languages to be considered for classification as a "Classical Language",[145]

High antiquity of its early texts/recorded history over a period of 1500–2000 years; a body of ancient literature/texts, which is considered a valuable heritage by generations of speakers; the literary tradition be original and not borrowed from another speech community; the classical language and literature being distinct from modern, there may also be a discontinuity between the classical language and its later forms or its offshoots.

Benefits

As per Government of India's Resolution No. 2-16/2004-US(Akademies) dated 1 November 2004, the benefits that will accrue to a language declared as a "Classical Language" are:

- Two major international awards for scholars of eminence in Classical Indian Languages are awarded annually.

- A Centre of Excellence for Studies in Classical Languages is set up.

- The University Grants Commission will be requested to create, to start with at least in the Central Universities, a certain number of Professional Chairs for Classical Languages for scholars of eminence in Classical Indian Languages.[149]

Other local languages and dialects

The 2001 census identified the following native languages having more than one million speakers. Most of them are dialects/variants grouped under Hindi.[72]

| Languages | No. of native speakers[72] |

|---|---|

| Bhojpuri | 33,099,497 |

| Rajasthani | 18,355,613 |

| Magadhi/Magahi | 13,978,565 |

| Chhattisgarhi | 13,260,186 |

| Haryanvi | 7,997,192 |

| Marwari | 7,936,183 |

| Malvi | 5,565,167 |

| Mewari | 5,091,697 |

| Khorth/Khotta | 4,725,927 |

| Bundeli | 3,072,147 |

| Bagheli | 2,865,011 |

| Pahari | 2,832,825 |

| Laman/Lambadi | 2,707,562 |

| Awadhi | 2,529,308 |

| Harauti | 2,462,867 |

| Garhwali | 2,267,314 |

| Nimadi | 2,148,146 |

| Sadan/Sadri | 2,044,776 |

| Kumauni | 2,003,783 |

| Dhundhari | 1,871,130 |

| Tulu | 1,722,768 |

| Surgujia | 1,458,533 |

| Bagri Rajasthani | 1,434,123 |

| Banjari | 1,259,821 |

| Nagpuria | 1,242,586 |

| Surajpuri | 1,217,019 |

| Kangri | 1,122,843 |

Practical problems

India has several languages in use; choosing any single language as an official language presents problems to all those whose "mother tongue" is different. However, all the boards of education across India recognise the need for training people to one common language.[150] There are complaints that in North India, non-Hindi speakers have language trouble. Similarly, there are complaints that North Indians have to undergo difficulties on account of language when travelling to South India. It is common to hear of incidents that result due to friction between those who strongly believe in the chosen official language, and those who follow the thought that the chosen language(s) do not take into account everyone's preferences.[151] Local official language commissions have been established and various steps are being taken in a direction to reduce tensions and friction.

Language conflicts

There are conflicts over linguistic rights in India. The first major linguistic conflict, known as the Anti-Hindi agitations of Tamil Nadu, took place in Tamil Nadu against the implementation of Hindi as the official language of India. Political analysts consider this as a major factor in bringing DMK to power and leading to the ousting and nearly total elimination of the Congress party in Tamil Nadu.[152] Strong cultural pride based on language is also found in other Indian states such as Assam, Odisha, Karnataka, West Bengal, Punjab and Maharashtra. To express disapproval of the imposition of Hindi on its states' people as a result of the central government, the government of Maharashtra made the state language Marathi mandatory in educational institutions of CBSE and ICSE through Class/Grade 10.[153]

The Government of India attempts to assuage these conflicts with various campaigns, coordinated by the Central Institute of Indian Languages, Mysore, a branch of the Department of Higher Education, Language Bureau, and the Ministry of Human Resource Development.

Writing systems

Most languages in India are written in scripts derived from Brahmi.[154].These include Devanagari, Tamil, Telugu, Kannada, Meitei Mayek, Odia, Eastern Nagari – Assamese/Bengali, Gurumukhi and other.Urdu is written in a script derived from Arabic.A few minor languages such as Santali use independent scripts.

Various Indian languages have their own scripts. Hindi, Marathi, Maithili[155] and Angika are languages written using the Devanagari script. Most major languages are written using a script specific to them, such as Assamese (Asamiya)[156][157][158] with Asamiya,[159] Bengali with Bengali, Punjabi with Gurmukhi, Meitei with Meitei Mayek, Odia with Odia script, Gujarati with Gujarati, etc. Urdu and sometimes Kashmiri, Saraiki and Sindhi are written in modified versions of the Perso-Arabic script. With this one exception, the scripts of Indian languages are native to India. Languages like Kodava that didn't have a script whereas Tulu which had a script adopted Kannada due to its readily available printing settings; these languages have taken up the scripts of the local official languages as their own and are written in the Kannada script.[160]

Development of Odia script

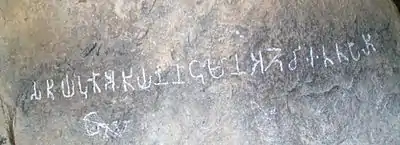

Development of Odia script Tamil-Brahmi inscription in Jambaimalai.

Tamil-Brahmi inscription in Jambaimalai. Silver coin issued during the reign of Rudra Singha with Assamese inscriptions.

Silver coin issued during the reign of Rudra Singha with Assamese inscriptions. North Indian Brahmi found in Ashok pillar.

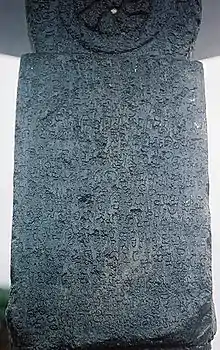

North Indian Brahmi found in Ashok pillar. The Halmidi inscription, the oldest known inscription in the Kannada script and language. The inscription is dated to the 450 CE - 500 CE period.

The Halmidi inscription, the oldest known inscription in the Kannada script and language. The inscription is dated to the 450 CE - 500 CE period.

See also

- List of endangered languages in India

- List of languages by number of native speakers in India

- National Translation Mission

- Romanization of Sindhi

- Indo-Portuguese creoles

- Languages of Pakistan

- Languages of Bangladesh

- Languages of Sri Lanka

- Languages of Maldives

- Languages of Nepal

- Languages of Myanmar

- Languages of Malaysia

- Languages of Singapore

- Languages of Mauritius

- Languages of Réunion

- Languages of Fiji

- Languages of Guyana

- Languages of Trinidad and Tobago

- Tamil diaspora

- Telugu diaspora

- Caribbean Hindustani

- Fiji Hindi

References

- "Constitution of India". Archived from the original on 2 April 2012. Retrieved 21 March 2012.

- "Official Language Act | Government of India, Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology". meity.gov.in. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- Salzmann, Zdenek; Stanlaw, James; Adachi, Nobuko (8 July 2014). Language, Culture, and Society: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology. Westview Press. ISBN 9780813349558 – via Google Books.

- "Official Language – The Union -Profile – Know India: National Portal of India". Archive.india.gov.in. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "India". Ethnologue. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- "Indo-Aryan languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- "Hindi languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- Moseley, Christopher (10 March 2008). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79640-2.

- "What countries have the most languages?".

- Aadithiyan, Kavin (10 November 2016). "Notes and Numbers: How the New Currency May Resurrect an Old Language Debate". Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- "Article 343 in The Constitution Of India 1949". Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- Khan, Saeed (25 January 2010). "There's no national language in India: Gujarat High Court". The Times of India. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- Press Trust of India (25 January 2010). "Hindi, not a national language: Court". The Hindu. Ahmedabad. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- Languages Included in the Eighth Schedule of the Indian Constution Archived 4 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- "Census Data 2001 : General Note". Census of India. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Abidi, S.A.H.; Gargesh, Ravinder (2008). "4. Persian in South Asia". In Kachru, Braj B. (ed.). Language in South Asia. Kachru, Yamuna & Sridhar, S.N. Cambridge University Press. pp. 103–120. ISBN 978-0-521-78141-1.

- Bhatia, Tej K and William C. Ritchie. (2006) Bilingualism in South Asia. In: Handbook of Bilingualism, pp. 780-807. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing

- "Decline of Farsi language – The Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Retrieved 25 October 2015.

- Nehru, Jawaharlal; Gandhi, Mohandas (1937). The question of language: Issue 6 of Congress political and economic studies. K. M. Ashraf.

- Hardgrave, Robert L. (August 1965). The Riots in Tamilnad: Problems and Prospects of India's Language Crisis. Asian Survey. University of California Press.

- https://www.nagpurtoday.in/maharashtra-to-join-anti-hindi-stir-at-bengaluru/08031021

- Avari, Burjor (11 June 2007). India: The Ancient Past: A History of the Indian Sub-Continent from C. 7000 BC to AD 1200. Routledge. ISBN 9781134251629.

- Andronov, Mikhail Sergeevich (1 January 2003). A Comparative Grammar of the Dravidian Languages. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 9783447044554.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521771110.

- Kachru, Yamuna (1 January 2006). Hindi. London Oriental and African language library. John Benjamins Publishing. p. 1. ISBN 90-272-3812-X.

- Brass, Paul R. (2005). Language, Religion and Politics in North India. iUniverse. p. 129. ISBN 978-0-595-34394-2.

- Kulshreshtha, Manisha; Mathur, Ramkumar (24 March 2012). Dialect Accent Features for Establishing Speaker Identity: A Case Study. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-4614-1137-6.

- Robert E. Nunley; Severin M. Roberts; George W. Wubrick; Daniel L. Roy (1999), The Cultural Landscape an Introduction to Human Geography, Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-080180-1,

... Hindustani is the basis for both languages ...

- Aijazuddin Ahmad (2009). Geography of the South Asian Subcontinent: A Critical Approach. Concept Publishing Company. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-81-8069-568-1. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Naheed Saba (18 September 2013). "2. Multilingualism". Linguistic heterogeneity and multilinguality in India: a linguistic assessment of Indian language policies (PDF). Aligarh: Aligarh Muslim University. pp. 61–68. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2014). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World (Seventeenth edition) : India". Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Ethnologue : Languages of the World (Seventeenth edition) : Statistical Summaries Archived 17 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Singh, Shiv Sahay (22 July 2013). "Language survey reveals diversity". The Hindu. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- Banerjee, Paula; Chaudhury, Sabyasachi Basu Ray; Das, Samir Kumar; Bishnu Adhikari (2005). Internal Displacement in South Asia: The Relevance of the UN's Guiding Principles. SAGE Publications. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-7619-3329-8. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Dasgupta, Jyotirindra (1970). Language Conflict and National Development: Group Politics and National Language Policy in India. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley. Center for South and Southeast Asia Studies. p. 47. ISBN 9780520015906.

- Mallikarjun, B. (5 August 2002). "Mother Tongues of India According to the 1961 Census". Languages in India. M. S. Thirumalai. 2. ISSN 1930-2940. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Vijayanunni, M. (26–29 August 1998). "Planning for the 2001 Census of India based on the 1991 Census" (PDF). 18th Population Census Conference. Honolulu, Hawaii, USA: Association of National Census and Statistics Directors of America, Asia, and the Pacific. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 November 2008. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Mallikarjun, B. (7 November 2001). "Languages of India according to 2001 Census". Languages in India. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- Wischenbart, Ruediger (11 February 2013). The Global EBook Market: Current Conditions & Future Projections. "O'Reilly Media, Inc.". p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4493-1999-1. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- Schiffrin, Deborah; Fina, Anna De; Nylund, Anastasia (2010). Telling Stories: Language, Narrative, and Social Life. Georgetown University Press. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-58901-674-3. Retrieved 18 December 2014.

- "CENSUS OF INDIA 2011, PAPER 1 OF 2018, LANGUAGE INDIA,STATES AND UNION TERRITORIES" (PDF). Census of India Website. Retrieved 29 August 2019.

- Census Data 2001 General Notes|access-date = 29 August 2019

- ORGI. "Census of India: Comparative speaker's strength of Scheduled Languages-1951, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991 ,2001 and 2011" (PDF).

- "How many Indians can you talk to?".

- "How languages intersect in India". Hindustan Times.

- "Summary by language size". Ethnologue. Retrieved 12 March 2019. For items below #26, see individual Ethnologue entry for each language.

- "India : Languages". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- INDIA STATISTICS REPORT

- "Indo-Aryan languages". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- West, Barbara A. (1 January 2009). Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania. Infobase Publishing. p. 713. ISBN 978-1-4381-1913-7.

- Levinson, David; Christensen, Karen (2002). Encyclopedia of Modern Asia: China-India relations to Hyogo. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-684-31243-9.

- Ishtiaq, M. (1999). Language Shifts Among the Scheduled Tribes in India: A Geographical Study. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass Publishers. pp. 26–27. ISBN 9788120816176. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- Memorandum of Settlement on Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC)

- Kachru, Braj B.; Kachru, Yamuna; Sridhar, S. N. (27 March 2008). Language in South Asia. ISBN 9780521781411. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Robbins Burling. "On "Kamarupan"" (PDF). Sealang.net. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Niclas Burenhult. "Deep linguistic prehistory with particular reference to Andamanese" (PDF). Working Papers. Lund University, Dept. of Linguistics (45): 5–24. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- Anderson, Gregory D. S. (2007). The Munda Verb: Typological Perspectives. Walter de Gruyter. p. 6. ISBN 978-3-11-018965-0.

- Anderson, G. D. S. (6 April 2010). "Austro-asiatic languages". In Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4.

- Greenberg, Joseph (1971). "The Indo-Pacific hypothesis." Current trends in linguistics vol. 8, ed. by Thomas A. Sebeok, 807.71. The Hague: Mouton.

- Abbi, Anvita (2006). Endangered Languages of the Andaman Islands. Germany: Lincom GmbH.

- "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 December 2014. Retrieved 17 September 2016.

- "C-17 : Population by Bilingualism and Trilingualism". Census of India Website.

- https://censusindia.gov.in/2011census/C-17.html

- Guha, Ramachandra (10 February 2011). "6. Ideas of India (section IX)". India After Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy. Pan Macmillan. pp. 117–120. ISBN 978-0-330-54020-9. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- "Constitution of India as of 29 July 2008" (PDF). The Constitution Of India. Ministry of Law & Justice. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2014. Retrieved 13 April 2011.

- Thomas Benedikter (2009). Language Policy and Linguistic Minorities in India: An Appraisal of the Linguistic Rights of Minorities in India. LIT Verlag Münster. pp. 32–35. ISBN 978-3-643-10231-7. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- "Official Languages Act, 1963 (with amendments)" (PDF). Indian Railways. 10 May 1963. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- "Chapter 7 – Compliance of Section 3(3) of the Official Languages Act, 1963" (PDF). Committee of Parliament on Official Language report. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2012.

- "The force of words". Time. 19 February 1965. Retrieved 3 January 2015.

- Forrester, Duncan B. (Spring–Summer 1966), "The Madras Anti-Hindi Agitation, 1965: Political Protest and its Effects on Language Policy in India", Pacific Affairs, 39 (1/2): 19–36, doi:10.2307/2755179, JSTOR 2755179

- "Statement 1 – Abstract of Speakers' Strength of Languages and Mother Tongues – 2001". Government of India. Archived from the original on 14 October 2013. Retrieved 11 December 2014.

- Hindi (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- "Rajya Sabha MPs can now speak in any of 22 scheduled languages in the house". Retrieved 24 July 2018.

- Ács, Judit; Pajkossy, Katalin; Kornai, András (2017). "Digital vitality of Uralic languages" (PDF). Acta Linguistica Academica. 64 (3): 327–345. doi:10.1556/2062.2017.64.3.1.

- Joseph, Manu (17 February 2011). "India Faces a Linguistic Truth: English Spoken Here". The New York Times.

- Snoj, Jure. "20 maps of India that explain the country". Call Of Travel. Retrieved 17 April 2016.

- Pandharipande, Rajeshwari (2002), "Minority Matters: Issues in Minority Languages in India" (PDF), International Journal on Multicultural Societies, 4 (2): 3–4

- "Memorandum of Settlement on Bodoland Territorial Council (BTC)". South Asia Terrorism Portal. 10 February 2003. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- ANI (10 September 2014). "Assam government withdraws Assamese as official language in Barak Valley, restores Bengali". DNA India. Retrieved 25 December 2014.

- "DOL". Archived from the original on 20 June 2010. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Commissioner Linguistic Minorities". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- Language in India

- "THE OFFICIAL LANGUAGES ACT, 1963". Archived from the original on 1 June 2009. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "National Portal of India : Know India : Profile". Archived from the original on 17 April 2007. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Committee of Parliament on Official Language report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 February 2012. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 21 February 2018.

- "Summary by language size". Ethnologue. Retrieved 21 February 2019.

- "The Bengali Language at Cornell – Department of Asian Studies". Lrc.cornell.edu. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Chu, Emily. "UNESCO Dhaka Newsletter" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- "Language and Mother Tongue". MHA, Gov. of India.

- 2001 Census of India#Language demographics

- Stein, Burton (November 1977), "Circulation and the Historical Geography of Tamil Country", The Journal of Asian Studies, 37 (1): 7–26, doi:10.2307/2053325, JSTOR 2053325

- Steever, Sanford B. "The Dravidian languages", First Published (1998), pp. 6–9. ISBN 0-415-10023-2

- Kamil Zvelebil, The Smile of Murugan Leiden 1973, p11-12

- The I.A.S. Tamil Medical Manuscript Collection, UNESCO, archived from the original on 27 October 2008, retrieved 13 September 2012

- Saiva Manuscript in Pondicherry, UNESCO, archived from the original on 4 August 2009, retrieved 13 September 2012

- Memory of the World Register: India, UNESCO, archived from the original on 12 October 2009, retrieved 13 September 2012

- Sandra Küng (6 June 2013). "Translation from Gujarati to English and from English to Gujarati – Translation Services". Archived from the original on 17 October 2014.

- Zvelebil in H. Kloss & G.D. McConnell; Constitutional languages, p.240, Presses Université Laval, 1 Jan 1989, ISBN 2-7637-7186-6

- Steever, S. B., The Dravidian Languages (Routledge Language Family Descriptions), 1998, p.129, London, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-10023-2

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju, The Dravidian Languages (Cambridge Language Surveys), 2003, p.23, Cambridge and London: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-77111-0

- H. Kloss & G.D. McConnell, Constitutional languages, p.239, Presses Université Laval, 1 Jan 1989, ISBN 2-7637-7186-6

- Narasimhacharya R; History of Kannada Literature, p.2, 1988, Asian Educational Services, New Delhi, ISBN 81-206-0303-6

- Sastri, Nilakanta K.A.; A history of South India from prehistoric times to the fall of Vijayanagar, 1955, 2002, India Branch of Oxford University Press, New Delhi, ISBN 0-19-560686-8

- Das, Sisir Kumar; A History of Indian Literature, 500–1399: From Courtly to the Popular, pp.140–141, Sahitya Akademi, 2005, New Delhi, ISBN 81-260-2171-3

- R Zydenbos in Cushman S, Cavanagh C, Ramazani J, Rouzer P, The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics: Fourth Edition, p.767, Princeton University Press, 2012, ISBN 978-0-691-15491-6

- Datta, Amaresh; Encyclopaedia of Indian literature – vol 2, p.1717, 1988, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 81-260-1194-7

- Sheldon Pollock in Dehejia, Vidya; The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art, p.5, chapter:The body as Leitmotif, 2013, Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-14028-7

- Garg, Gaṅgā Rām; Encyclopaedia of the Hindu World, Volume 1, p.68, Concept Publishing Company, 1992, New Delhi, ISBN 978-81-7022-374-0

- Shipley, Joseph T.; Encyclopedia of Literature – Vol I, p.528, 2007, READ BOOKS, ISBN 1-4067-0135-1

- Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student’s Handbook, Edinburgh, p. 300.

- "Dakshina Kannada District: Dakshin Kannada also called South Canara – coastal district of Karnataka state". Karnatakavision.com. Retrieved 20 February 2012.

- "Kodagu-Kerala association is ancient". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 26 November 2008.

- "Virajpet Kannada Sahitya Sammelan on January 19". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 9 December 2008.

- Asher, R; Kumari, T. C. (11 October 2013). Malayalam. Taylor & Francis. p. xxiv. ISBN 978-1-136-10084-0. Retrieved 19 December 2016.

- Epigraphy – Grantha Script Archived 11 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology

- Andronov, Mikhail Sergeevich. A Grammar of the Malayalam Language in Historical Treatment. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1996.

- "Mixed views emerge as Orissa becomes Odisha". India Today. Retrieved 10 November 2011.

- "Scheduled Languages in descending order of speaker's strength – 2011" (PDF). Registrar General and Census Commissioner of India.

- CENSUS OF INDIA 2011. "LANGUAGE" (PDF). Government of India. p. 12.

- Pattanayak, Debi Prasanna; Prusty, Subrat Kumar. Classical Odia (PDF). Bhubaneswar: KIS Foundation. p. 54. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- Kumarl, Chethan (19 July 2016). "Manuscript mission: Tibetan beats all but three Indian languages – Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 11 November 2016.

- "Common Languages of India – Popular Indian Language – Languages Spoken in India – Major Indian Languages". India-travel-agents.com. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Languages Spoken by More Than 10 Million People". Archived from the original on 3 December 2007. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Maithili". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Promotion of Maithili Language

- Maithili Language as the second official

- Zee News Report

- Rise in Hindi language speakers, Statement-4 Retrieved on 22 February 2020

- Sah, K. K. (2013). "Some perspectives on Maithili". Nepalese Linguistics (28): 179–188.

- Brass, P. R. (2005). Language, Religion and Politics in North India. Lincoln: iUniverse. ISBN 0-595-34394-5. Retrieved 1 April 2017.

- Yadava, Y. P. (2013). Linguistic context and language endangerment in Nepal. Nepalese Linguistics 28: 262–274.

- Singh, P., & Singh, A. N. (2011). Finding Mithila between India's Centre and Periphery. Journal of Indian Law & Society 2: 147–181.

- "India sets up classical languages". BBC. 17 September 2004. Retrieved 1 May 2007.

- "Didi, Naveen face-off over classical language status". The New Indian Express. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "Bangla O Bangla Bhasha Banchao Committee". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- Clara Lewis (16 April 2018). "Clamour grows for Marathi to be given classical language status". The Times of India.

- "Front Page : Tamil to be a classical language". Chennai, India: The Hindu. 18 September 2004. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "National : Sanskrit to be declared classical language". Chennai, India: The Hindu. 28 October 2005. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "Declaration of Telugu and Kannada as classical languages". Press Information Bureau. Ministry of Tourism and Culture, Government of India. Retrieved 31 October 2008.

- "'Classical' status for Malayalam". Thiruvananthapuram, India: The Hindu. 24 May 2013. Retrieved 25 May 2013.

- "Odia gets classical language status". The Hindu. 20 February 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- "Milestone for state as Odia gets classical language status". The Times of India.

- "CLASSICAL LANGUAGE STATUS TO KANNADA". Press Information Bureau, Government of India. 8 August 2006. Retrieved 6 November 2008.

- Singh, Binay (5 May 2013). "Removal of Pali as UPSC subject draws criticism". The Times of India. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- "Reviving classical languages – Latest News & Updates at Daily News & Analysis". Dnaindia.com. 13 August 2015. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Marathi may become classical language". The Indian Express. 4 July 2013.

- "Classical Status to Oriya Language". Pib.nic.in (Press release). 14 August 2013.

- "Language and Globalization: Center for Global Studies at the University of Illinois". Archived from the original on 10 May 2013.

- Prakash, A Surya (27 September 2007). "Indians are no less racial". The Pioneer. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007.

- Guha, Ramachandra (16 January 2005). "Hindi against India". Chennai, India: The Hindu. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- "Marathi a must in Maharashtra schools". IBNLive. 3 February 2010. Archived from the original on 12 August 2011. Retrieved 1 August 2010.

- Peter T. Daniels; William Bright (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. pp. 384–. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- http://www.ethnologue.com/17/language/mai/

- "File:Indoarische Sprachen.png". Commons.wikipedia.org. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Jain, Danesh; Cardona, George (26 July 2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. ISBN 9781135797119. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Mohanty, P. K. (2006). Encyclopaedia of Scheduled Tribes in India. ISBN 9788182050525. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- Singh, Vijay; Sharma, Nayan; Ojha, C. Shekhar P. (29 February 2004). The Brahmaputra Basin Water Resources. ISBN 9781402017377. Retrieved 28 December 2017.

- "Kodava". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Languages of India |

- Linguistic map of India with a detailed map of the Seven Sister States (India) at Muturzikin.com

- Languages and Scripts of India

- Diversity of Languages in India

- A comprehensive federal government site that offers complete info on Indian Languages

- Technology Development for Indian Languages, Government of India

- Languages Spoken in Himachal Pradesh - Himachal Pariksha