Arbëreshë people

The Arbëreshë (pronounced [aɾbəˈɾɛʃ]; Albanian: Arbëreshët e Italisë or Shqiptarët e Italisë), also known as Albanians of Italy or Italo-Albanians, are an Albanian ethnolinguistic group in Southern Italy, mostly concentrated in scattered villages in the regions of Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise and Sicily.[5] They are the descendants of mostly Tosk Albanian refugees, who fled from Albania between the 14th and the 18th centuries in consequence of the Ottoman invasion of the Balkans.

Albanians of Italy · Italo-Albanesi | |

|---|---|

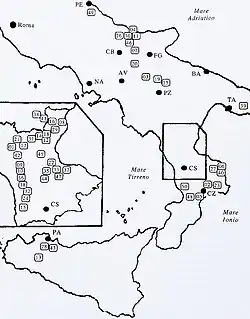

The Albanian settlements of Italy (numbered list) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

Abruzzo, Apulia, Basilicata, Calabria, Campania, Molise, Sicily | 100,000[1][2][3][4] |

| Languages | |

| Albanian (Arbëresh dialects), Italian | |

| Religion | |

Italo-Albanian Byzantine Catholic Church (minority Catholicism (Roman Rite)) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Albanians Albanian diaspora Arvanites | |

| Part of a series on |

| Albanians |

|---|

|

| By country |

|

Native Albania · Kosovo Croatia · Greece · Italy · Montenegro · North Macedonia · Serbia Diaspora Australia · Bulgaria · Denmark · Egypt · Finland · Germany · Norway · Romania · South America · Spain · Sweden · Switzerland · Turkey · Ukraine · United Kingdom · United States |

| Culture |

| Architecture · Art · Cuisine · Dance · Dress · Literature · Music · Mythology · Politics · Religion · Symbols · Traditions · Fis |

| Religion |

| Christianity (Catholicism · Orthodoxy · Protestantism) · Islam (Sunnism · Bektashism) · Judaism |

| Languages and dialects |

|

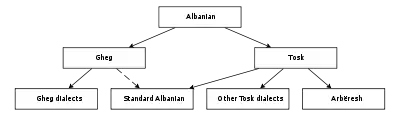

Albanian Gheg (Arbanasi · Upper Reka · Istrian) · Tosk (Arbëresh · Arvanitika · Calabria Arbëresh · Cham · Lab) |

| History of Albania |

During the Middle Ages, the Arbëreshë settled in Southern Italy in several waves of migration, following the establishment of the Kingdom of Albania, the death of the Albanian national hero Gjergj Kastrioti Skënderbeu and the gradual conquest of Albania and the Byzantine Empire by the Ottomans.

Their culture is determined by the main features that are found in language, religion, traditions, customs, art and gastronomy, still zealously preserved, with the awareness of belonging to a specific ethnic group. Over the centuries, the Arbëreshë have managed to maintain and develop their identities, thanks to their cultural value exercised mainly by the two religious communities of the Byzantine Rite based in Calabria, the Corsini College in 1732 then Corsini Adriano College of San Benedetto Ullano in 1794 and the Arbëreshë Seminary of Palermo in 1735, which was then transferred to Piana degli Albanesi in 1945.

Nowadays, most of the fifty Arbëreshë communities are adherents to the Italo-Albanian Church, an Eastern Catholic Church. They belong to two eparchies, the Lungro, for the Arbëreshë of Continental Italy, the Piana degli Albanesi, for the Arbëreshë of Sicily, and the Monastery of Grottaferrata, whose Basilian monks come largely from the Albanian settlements of Italy. The church is the most important organization for maintaining the characteristic religious, ethnic, linguistic and traditional identity of the Arbëreshë community.

The Arbëreshë speak Arbëresh, a variant of Albanian that descends from Tosk Albanian. This Albanian dialect is of particular interest to students of the modern Albanian language as it retains speech sounds, morphosyntactic and vocabulary elements of the language spoken in pre-Ottoman Albania. In Italy, Arbëreshë is protected by law number 482/99, concerning the protection of the historic linguistic minorities.[6]

The Arbëreshë are scattered throughout southern Italy and Sicily and in small numbers also in other parts of Italy. They are in great numbers in North and South America, especially in the US, Brazil, Chile, Argentina, Mexico, Venezuela, Uruguay and Canada. It is estimated that there are about 100,000 Italo-Albanians (400,000 if including those outside of Italy); they constitute one of the oldest and largest minorities in Italy. Being Italian and Arbëreshë are both central to Italo-Albanians' identity.[7] When speaking about their "nation", Arbëresh use the term Arbëria, a loose geographical term for the scattered villages in southern Italy which use Arbëresh language. They are proud of their Albanian ethnicity, identity and culture,[8] but also identify themselves as Italian nationals, since they have lived in Italy for hundreds of years.[7]

In the light of historical events, the secular continuity of the Albanian presence in Italy is exceptional. In 2017, with the Republic of Albania, an official application for inclusion of the Arbëresh people has been submitted to the UNESCO as a living human and social immaterial patrimony of humanity.[9][10]

History

Ethnonym

In the Middle Ages, the native Albanians in the area of Albania called their country Arbëri or Arbëni and referred to themselves as Arbëreshë or Arbëneshë.[11][12] In the sixteenth century, the toponym Shqipëria and the demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria and Arbëresh respectively. Nowadays, only the Albanians in Italy, whose ancestors immigrated from the Middle Ages, are called Arbëresh and the language Arbërisht. The term Arbëreshë is also used as an endonym by the Arvanites in Greece.

Early migrations

.jpg.webp)

2.jpg.webp)

The Arbëreshë, between the 11th and 14th centuries, moved in small groups towards central and southern Albania and the north and south of Greece (Thessaly, Corinth, Peloponnesus, Attica) where they founded colonies. Their military skill made them favorite mercenaries of the Franks, Catalans, Italians and Byzantines.

The invasion of the Balkans by the Ottoman Turks in the 15th century forced many Arbëreshë to emigrate from Albania and Epirus to the south of Italy. There were several waves of migrations. Indeed, in 1448, the King of Naples Alfonso V of Aragon appealed to Skanderbeg in suppressing a revolt at Naples. Skanderbeg sent a force under the leadership of Demetrio Reres, and his two sons. Following a request of Albanian soldiers, King Alfonso granted land to them and they were settled in twelve villages in the mountainous area called Catanzaro in 1448. A year later the sons of Demetrio, George and Basil along with other Albanians were settled in four villages in the region of Sicily.[14]

In 1459, the son of Alfonso, king Ferdinand I of Naples again requested the help of Skanderbeg. This time, the legendary leader himself came to Italy with his troops ruled by one of his general Luca Baffa, to end a French-supported insurrection. Skanderbeg was appointed as the leader of the combined Neapolitan-Albanian army and, after victories in two decisive battles, the Albanian soldiers effectively defended Naples. This time they were rewarded with land east of Taranto in Apulia, populating 15 other villages.[15]

After the death of Skanderbeg in 1468, the organized Albanian resistance against the Ottomans came to an end. Like much of the Balkans, Albania became subject to the invading Turks. Many of its people under the rule of Luca Baffa and Marco Becci fled to the neighboring countries and settled in a few villages in Calabria. From the time of Skanderbeg's death until 1480 there were constant migrations of Albanians to the Italian coast. Throughout the 16th century, these migrations continued and other Albanian villages were formed on Italian soil.[16] The new immigrants often took up work as mercenaries hired by the Italian armies.

Another wave of emigration, between 1500 and 1534, relates to Arbëreshë from central Greece. Employed as mercenaries by Venice, they had to evacuate the colonies of the Peloponnese with the assistance of the troops of Charles V, as the Turks had invaded that region. Charles V established these troops in Italy of the South to reinforce defense against the threat of Turkish invasion. Established in insular villages (which enabled them to maintain their culture until the 20th century), Arbëreshë were, traditionally, soldiers for the Kingdom of Naples and the Republic of Venice, from the Wars of Religion to the Napoleonic invasion.

Later migrations

The wave of migration from southern Italy to the Americas in 1900–1910 and 1920–1940 depopulated approximately half of the Arbëreshë villages, and subjected the population to the risk of cultural disappearance, despite the beginning of a cultural and artistic revival in the 19th century.

Since the end of communism in Albania in 1990, there has been a wave of immigration into Arbëreshë villages by Albanians.

Ethnographic map: 1859 depicting the Albanian population in green

Ethnographic map: 1859 depicting the Albanian population in green Albanian ethno-linguistic territories

Albanian ethno-linguistic territories

Distribution

.jpg.webp)

The Arbëresh villages contains two or three names, an Italian one as well as one or two native Arbëresh names by which villagers know the place. The Arbëreshë communities are divided into numerous ethnic islands corresponding to different areas of southern Italy. However, some places have already lost their original characteristics and the language, and others have totally disappeared. Today, Italy has 50 communities of Arbëreshë origin and culture, 41 municipalities and 9 villages, spread across seven regions of southern Italy, forming a population of about 100,000.[1][2] Some cultural islands survive in the metropolitan areas of Milan, Chieri, Turin, Rome, Naples, Bari, Cosenza, Crotone and Palermo. In the rest of the world, following the migrations of the twentieth century to countries such as Germany, Canada, Chile, Brazil, Argentina, Mexico, Venezuela, Uruguay and the United States, there are strong communities that keep Arbëreshë traditions alive.

The full list of the Arbëresh Communities in Italy is:[17]

- Abruzzo

- Molise

- Province of Campobasso

- Campomarino: Këmarini

- Montecilfone: Munxhufuni

- Portocannone: Portkanuni

- Ururi: Rùri

- Province of Campobasso

- Campania

- Province of Avellino

- Greci: Katundi

- Province of Avellino

- Apulia

- Province of Foggia

- Casalvecchio di Puglia: Kazallveqi

- Chieuti: Qefti

- Provincia di Taranto

- San Marzano di San Giuseppe: Shën Marcani

- Province of Foggia

- Basilicata

- Province of Potenza

- Barile: Barilli

- Ginestra: Zhura

- Maschito: Mashqiti

- Rionero in Vulture:[18] A-Rionero

- San Costantino Albanese: Shën Kostandini Arbëresh

- San Paolo Albanese: Shën Pali Arbëresh

- Province of Potenza

- Calabria

- Province of Catanzaro

- Andali: Andalli

- Caraffa di Catanzaro: Garafa

- Marcedusa: Marçëdhuza

- Vena di Maida (frazione of Maida): Vina

- Province of Cosenza

- Acquaformosa: Firmoza

- Cantinella (frazione of Corigliano-Rossano): Kantinela

- Cerzeto (in the commune of Cerzeto): Qana

- Castroregio: Kastërnexhi

- Cavallerizzo (frazione of Cerzeto): Kajverici

- Civita: Çifti

- Eianina (frazione of Frascineto): Purçìll

- Falconara Albanese: Fullkunara

- Farneta (frazione of Castroregio): Farneta

- Firmo: Ferma

- Frascineto: Frasnita

- Lungro: Ungra

- Macchia Albanese (frazione of San Demetrio Corone): Maqi

- Malito

- Marri (frazione of San Benedetto Ulolano): Allimarri

- Mongrassano: Mungrasana

- Plataci: Pllatëni

- San Basile: Shën Vasili

- San Benedetto Ullano: Shën Benedhiti

- Santa Caterina Albanese: Picilia

- San Cosmo Albanese Strihàri

- San Demetrio Corone: Shën Mitri

- San Giorgio Albanese: Mbuzati

- San Giacomo di Cerzeto (frazione of Cerzeto): Shën Japku

- San Martino di Finita: Shën Mërtiri

- Santa Sofia d'Epiro: Shën Sofia

- Spezzano Albanese: Spixana

- Vaccarizzo Albanese: Vakarici

- Province of Crotone

- Carfizzi: Karfici

- Pallagorio: Puhëriu

- San Nicola dell'Alto Shën Kolli

- Province of Catanzaro

- Sicilia

- Province of Palermo

- Contessa Entellina: Kundisa

- Piana degli Albanesi: Hora e Arbëreshëvet

- Santa Cristina Gela: Sëndahstina

- Province of Palermo

Language

Arbëresh derives from the Tosk dialect spoken in southern Albania, and is spoken in Southern Italy in the regions of Calabria, Molise, Apulia, Basilicata, Campania, Abruzzi, and Sicily. All dialects of Arbëresh are closely related to each other but are not entirely mutually intelligible.

The Arbëresh language retains many archaisms of medieval Albanian from pre-Ottoman Albania in the 15th century. It also retains some Greek language elements, including vocabulary and pronunciation. It has also preserved some conservative features that were lost in mainstream Albanian Tosk. For example, it has preserved certain syllable-initial consonant clusters which have been simplified in Standard Albanian (cf. Arbërisht gluhë /ˈɡluxə/ ('language/tongue'), vs. Standard Albanian gjuhë /ˈɟuhə/). It sounds more archaic than Standard Albanian, but is close enough that it is written using the same Albanian alphabet as Standard Albanian. A Shqiptar (Albanian) listening to or reading Arbërisht is similar to a modern English speaker listening to or reading Shakespearean English. The Arbëresh language is of particular interest to students of the modern Albanian language as it represents the sounds, grammar, and vocabulary of pre-Ottoman Albania.

Arbërisht was commonly called Albanese ("Albanian" in Italian) in Italy until the 1990s. Until recently, Arbërisht speakers had only very imprecise notions about how related or unrelated their language was to Albanian. Until the 1980s Arbërisht was exclusively a spoken language, except for its written form used in the Italo-Albanian Church, and Arbëreshë people had no practical affiliation with the Standard Albanian language used in Albania, as they did not use this form in writing or in media. When a large number of immigrants from Albania began to enter Italy in the 1990s and came into contact with local Arbëreshë communities.

Since the 1980s, some efforts have been organized to preserve the cultural and linguistic heritage of the language. Arbërisht has been under a slow decline in recent decades, but is currently experiencing a revival in many villages in Italy. Figures such as Giuseppe Schirò Di Maggio have done much work on school books and other language learning tools in the language, producing two books Udha e Mbarë and Udhëtimi, both used in schools in the village of Piana degli Albanesi.

There is no official political, administrative or cultural structure which represents the Arbëresh community. Arbërësh is not one of the group of minority languages that enjoy the special protection of the State under Article 6 of the Italian Constitution. At the regional level, however, Arbërisht is accorded some degree of official recognition in the autonomy statutes of Calabria, Basilicata and Molise.

- In the case of Calabria, the region is to provide for recognition of the historical culture and artistic heritage of the populations of Arbëresh origin and to promote the teaching of the two languages in the places where they are spoken.

- Article 5 of the autonomy statute of Basilicata lays down that the regional authorities "shall promote renewed appreciation of the originality of the linguistic and cultural heritage of the local communities".

- Finally, the autonomy statute of the Molise region stipulates that the region "shall be the guardian of the linguistic and historical heritage and of the popular traditions of the ethnic communities existing in its territory and, by agreement with the interested municipalities, shall promote renewed appreciation of them".

In certain communes the local authorities support cultural and linguistic activities promoted by the Arbëresh communities and have agreed to the erection of bilingual road signs.[19] There are associations that try to protect the culture, particularly in the Province of Cosenza. The Arbëresh language is used in some private radios and publications. The fundamental laws of the areas of Molise, Basilicata and Calabria make reference to the Arbëresh language and culture. Nevertheless, the increase in training in the use of the written language has given some hope for the continuity of this culture.

Literature

Early Arbëreshë literature

The first work of Italo-Albanian literature was that of Sicilian archpriest Luca Matranga (1567–1619). The book was titled E mbsuama e krështerë (Christian Doctrine) and it was a simple religious translation in Arbëresh language, aiming at bringing Christianity closer to his people is Southern Italy. While during the 17th century there were no Arbëresh writers, in the 18th century there was Giulio Variboba (1724–1788, Jul Variboba), regarded by many Albanians as the first genuine poet in all of Albanian literature.[20] Born in San Giorgio Albanese (Mbuzati) and educated in Corsini Seminary in San Benedetto Ullano, after many polemics with local priest he went to exile in Rome in 1761 and there he published in 1762 his long lyric poem Ghiella e Shën Mëriis Virghiër (The life of Virgin Mary). The poem has been written entirely in dialect of San Giorgio and has about 4717 lines. Variboba is considered unique in Albanian literature for his poetic sensitivities and the variety of rhythmic expression. Another known artistic figure of that time was Nicola Chetta (1740–1803) known in Albanian as Nikollë Keta. As a poet he wrote verses both in Albanian and Greek language and he has also composed the first Albanian sonnet in 1777. Being a poet, lexicographer, linguist, historian, theologian and rector of Greek seminary, his variety and universality of work distinguish him from other writers of the period.[21] The most prominent figure among Arbëresh writers and the foremost figure of the Albanian nationalist movement in 19th-century Italy was that of Girolamo de Rada (Jeronim De Rada). Born the son of a parish priest of Italo-Albanian Catholic Church in Macchia Albanese (Maqi) in the mountains of Cosenza, De Rada attended the college of Saint Adrian in San Demetrio Corone. In October 1834, in accordance with his father's wishes, he registered at the Faculty of Law of the University of Naples, but the main focus of his interests remained folklore and literature. It was in Naples in 1836 that De Rada published the first edition of his best-known Albanian-language poem, the "Songs of Milosao", under the Italian title Poesie albanesi del secolo XV. Canti di Milosao, figlio del despota di Scutari (Albanian poetry from the 15th century. Songs of Milosao, son of the despot of Shkodra). His second work, Canti storici albanesi di Serafina Thopia, moglie del principe Nicola Ducagino, Naples 1839 (Albanian historical songs of Serafina Thopia, wife of prince Nicholas Dukagjini), was seized by the Bourbon authorities because of De Rada's alleged affiliation with conspiratorial groups during the Italian Risorgimento. The work was republished under the title Canti di Serafina Thopia, principessa di Zadrina nel secolo XV, Naples 1843 (Songs of Serafina Thopia, princess of Zadrina in the 15th century) and in later years in a third version as Specchio di umano transito, vita di Serafina Thopia, Principessa di Ducagino, Naples 1897 (Mirror of human transience, life of Serafina Thopia, princess of Dukagjin). His Italian-language historical tragedy I Numidi, Naples 1846 (The Numidians), elaborated half a century later as Sofonisba, dramma storico, Naples 1892 (Sofonisba, historical drama), enjoyed only modest public response. In the revolutionary year 1848, De Rada founded the newspaper L'Albanese d'Italia (The Albanian of Italy) which included articles in Albanian. This bilingual "political, moral and literary journal" with a final circulation of 3,200 copies was the first Albanian-language periodical anywhere.

De Rada was the harbinger and first audible voice of the Romantic movement in Albanian literature, a movement which, inspired by his unfailing energy on behalf of national awakening among Albanians in Italy and in the Balkans, was to evolve into the romantic nationalism characteristic of the Rilindja period in Albania. His journalistic, literary and political activities were instrumental not only in fostering an awareness for the Arbëresh minority in Italy but also in laying the foundations for an Albanian national literature.

The most popular of his literary works is the above-mentioned Canti di Milosao (Songs of Milosao), known in Albanian as Këngët e Milosaos, a long romantic ballad portraying the love of Milosao, a fictitious young nobleman in fifteenth-century Shkodra (Scutari), who has returned home from Thessalonica. Here, at the village fountain, he encounters and falls in love with Rina, the daughter of the shepherd Kollogre. The difference in social standing between the lovers long impedes their union until an earthquake destroys both the city and all semblance of class distinction. After their marriage abroad, a child is born. But the period of marital bliss does not last long. Milosao's son and wife soon die, and he himself, wounded in battle, perishes on a riverbank within sight of Shkodra.

Culture

Traditions and Folklore

Among the Arbëreshë the memory of Skanderbeg and his exploits was maintained and survived through songs, in the form of a Skanderbeg cycle.[22]

Gjitonía

"Gjitonia" is a form of neighbourhood typical of Arbëresh communities and widespread throughout the Arbëresh people. It comes from the Greek γειτονιά (geitonía). The Gjitonía functions as a microsystem around which the life of the horë (village) revolves; the Gjitonía is a smaller-scale version of the layout of the village often consisting of a small square towards which the alleys are oriented, surrounded by buildings that have openings towards a larger square (shesh) on diagonal angles. The name is usually taken from the families that live there. The social aspect of the Gjitonía is an ancient and historical structure where values of hospitality and solidarity between the families of the neighbourhood coexisted and where there was no difference of social class. Mainly for the Italian-Albanian communities, it is a world where relationships were so strong that they created real family relationships so much so that the Arbëreshe phrase Gjitoni gjirì ("neighbourhood relatives") is typical.[23]

Cuisine

The Arbëreshë cuisine is composed of the cuisines of Albania and Italy. The style of cooking and the food associated with it have evolved over many centuries from their Albanian origins to a mixed cuisine of Sicilian, Calabrian and Lucanian influences.

These traditional dishes are Piana degli Albanesi (Palermo, Sicily):

- Strangujët – A form of Gnocchi called Strangujtë made with flour by hand, flavoured with tomato sauce (lënk) and basil. Traditionally this dish was consumed by families seated around a floor level table of wood (zbrilla) on 14 September, the Festa e Kryqit Shejt (Exaltation of the Cross).

- Grurët – Boiled wheat dish flavored with olive oil, known as cuccìa in the Sicilian language. The tradition is to eat it on Festa e Sënda Lluçisë. Variations are the use of sweetened milk or ricotta with flakes of chocolate, orange peel and almonds.

- Kanojët – Cannoli, the universally famous Pianotto sweet pastry. Its culinary secret is waffle (shkorça) of flour, wine, lard and salt and filled with sweetened ricotta, and lastly sprinkled with sieved chocolate.

- Bukë – Arbëresh bread (bukë) is prepared with local hard grain flour and manufactured to a round and mostly leavened shape with natural methods. It is cooked in antique firewood furnaces (Tandoor). It is eaten warm flavored with olive oil (vaj i ullirit) and dusted with cheese or with fresh ricotta.

- Panaret – Arbëresh Easter bread shaped either into a circle or into two large braids and sprinkled with sesame seeds. It is adorned with red Easter eggs. The Easter eggs are dyed deep red to represent the blood of Christ, the eggs also represent new life and springtime. It is traditionally eaten during the Resurrection Meal. After 40 days of fasting, as per the Byzantine Catholic tradition, the Easter feast has to begin slowly, with a light meal after the midnight liturgy on Saturday night. The fast is generally broken with panaret.

- Loshkat and Petullat – Sweetened spherical or crushed shaped fried leavened dough. Eaten on the eve of E Mart e Madh Carnival.

- Të plotit – A sweet cake in various shaped with fig marmalade filling, one of the oldest Arbëresh dishes.

- Milanisë – Traditionally eaten on the Saint Joseph's Day (Festa e Shën Zefit) and Good Friday, is a pasta dish made with a sauce (lënk) of wild fennel paste, sardines and pine nuts.

- Udhose and Gjizë – Homemade cheese and ricotta normally dried outdoors.

- Likëngë – Pork sausages flavored with salt, pepper and seed of Fennel (farë mbrai).

- Llapsana – Forest Brussel sprout (llapsana) fried with garlic and oil.

- Dorëzët – Very thin home-made semolina spaghetti, cooked in milk and eaten on Ascension Day.

- Groshët – Soup made of fava beans, chickpeas and haricot beans.

- Verdhët – During Easter a kind of pie is prepared with eggs, lamb, ricotta, sheep cheese and (previously boiled) leaf stalks of golden thistle; in some villages, the young aerial parts of wild fennel are used instead.

Religion

The Italo-Albanian Catholic Church, particular church sui iuris, includes three ecclesiastical jurisdictions: the Eparchy of Lungro degli Italo-Albanesi for the Albanians of Southern Italy based in Lungro (CS); the Eparchy of Piana degli Albanesi for Albanians of Insular Italy based in Piana degli Albanesi (PA); the Territorial Abbacy of Santa Maria of Grottaferrata, with Basilian monks (O.S.B.I.) come from the Italo-Albanian communities, located in the only abbey and abbey church in Grottaferrata (RM).

The Italo-Albanian Catholic Church being a Byzantine enclave in the Latin West, is secularly inclined to ecumenism between the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church. It was the only abode of eastern Christianity from the end of the Middle Ages until the twentieth century in Italy.

There are institutions and religious congregations of the Byzantine rite in the territory of the Italo-Albanian Church: the Basilian Order of Grottaferrata, the Collegine Sisters of Sacra Famiglia, Piccole operaie dei Sacri Cuori and the congregation of the Basilian Sisters Daughters of Saint Macrina.

The Cathedral of Lungro of the Albanians of Southern Italy

The Cathedral of Lungro of the Albanians of Southern Italy The Cathedral of Piana degli Albanesi of the Albanians of Insular Italy

The Cathedral of Piana degli Albanesi of the Albanians of Insular Italy The Territorial Abbacy of Santa Maria of Grottaferrata with Basilian monks from the Italo-Albanian communities

The Territorial Abbacy of Santa Maria of Grottaferrata with Basilian monks from the Italo-Albanian communities

Physical appearance

A study from 1918 included 59 Arbëreshë men from Cosenza, Calabria, the result showed that fair hair was present in 27% of them. The same study also showed that the frequencies of light eyes and white skin, were 47% and 67% respectively. The Albanians, from this survey, are found to be overall less pigmented than the Calabrians. They are also taller (m. 1.64) and less dolichocephalic (cephalic index 80.6).[24]

Genetics

According to Sarno et al. 2015 there are many Y-DNA haplogroups present among Arbëreshë. Those haplogroups are also shared with their Italian and Balkan neighbours.[25] Arbereshe appear as slightly differentiated from native Southern Italians, and instead overlap with the other Southern Balkan populations of Albania and Kosovo.[26]

Notable Arbëreshë people

Gallery

Iconostasis in a church in Piana degli Albanesi, Sicily

Iconostasis in a church in Piana degli Albanesi, Sicily_(CS)..jpg.webp)

_(CS)._(4).jpg.webp)

Bilingual sign in Albanian and Italian in Maschito, Basilicata

Bilingual sign in Albanian and Italian in Maschito, Basilicata

Arbëresh craft-workshop in Piana degli Albanesi

Arbëresh craft-workshop in Piana degli Albanesi

Traditional costume Arbëreshe of San Martino di Finita in Calabria

Traditional costume Arbëreshe of San Martino di Finita in Calabria_(CS)%252C_Le_Vallje_2009._(5).jpg.webp) Albanian dance, Civita

Albanian dance, Civita Typical Arbëreshë female costumes of San Basile in Calabria

Typical Arbëreshë female costumes of San Basile in Calabria

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arbëreshë. |

References

- Fiorenzo Toso (2006). Baldini & Castoldi (ed.). Lingue d'Europa. La pluralità linguistica dei Paesi europei fra passato e presente. Roma. p. 90. ISBN 9788884908841. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- P. Bruni, ed. (2004). Arbëreshë: cultura e civiltà di un popolo. ISBN 9788824020091.

- "Ethnologue: Albanian, Arbëreshë". Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- "Currently there are about fifty Albanian-speaking centres in Italy, with a population estimated to be around 100,000, though there are no precise figures for the actual numbers of Italo-Albanians. The most recent precise figure is given in the census for 1921; the number of Albanian speakers was 80,282, far fewer than the 197 thousand mentioned in the study of A. Frega of 1997."

Amelia De Lucia; Giorgio Gruppioni; Rosalina Grumo; Gjergj Vinjahu (eds.). "Albanian Cultural Profile" (PDF). Dipartimento di Scienze Statistiche, Università degli Studi di Bari, Italia. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 4 May 2016. - Minni, C. Dino; Ciampolini, Anna Foschi (1990). Writers in transition: the proceedings of the First National Conference of Italian-Canadian Writers. Guernica Editions. pp. 63–4. ISBN 978-0-920717-26-4. Retrieved 30 September 2010.

- "Legge 482". Camera.it. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- Essays on Politics and Society Author Hasan Jashari Publisher lulu.com, 2015 ISBN 1-84511-031-5, ISBN 978-1-326-27184-8 p. 64

- Shkodra, arbëreshët dhe lidhjet italo-shqiptare. Universiteti i Shkodrës "Luigj Gurakuqi". 2013. ISBN 978-9928-4135-3-6.

- "Top Channel.tv Albania – Arbëreshët kërkojnë ndihmë nga Tirana: Të njihemi në UNESCO". Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Arbëreshët kërkojnë të anëtarësohen në UNESCO

- Casanova. "Radio-Arberesh.eu". Archived from the original on 2 April 2010. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Kristo Frasheri. History of Albania (A Brief Overview). Tirana, 1964.

- Elsie, Robert (2010). Historical dictionary of Albania. Lanham.

- The Italo-Albanian villages of southern Italy Issue 25 of Foreign field research program, report, National Research Council (U.S.) Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.)) Foreign field research program, sponsored by Office of Naval research, report ; no.25 Issue 25 of Report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of (National Academy of Sciences. National Research Council. Publication) Author George Nicholas Nasse Publisher National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, 1964 page 24-25 link

- The Italo-Albanian villages of southern Italy Issue 25 of Foreign field research program, report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.))) Foreign field research program, sponsored by Office of Naval research, report ; no.25 Issue 25 of Report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of (National Academy of Sciences. National Research Council. Publication) Author George Nicholas Nasse Publisher National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, 1964 page 25 link

- The Italo-Albanian villages of southern Italy Issue 25 of Foreign field research program, report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of Publication (National Research Council (U.S.))) Foreign field research program, sponsored by Office of Naval research, report ; no.25 Issue 25 of Report, National Research Council (U.S.). Division of Earth Sciences Volume 1149 of (National Academy of Sciences. National Research Council. Publication) Author George Nicholas Nasse Publisher National Academy of Sciences-National Research Council, 1964 page 26 link

- "Comunità albanesi d' Italia" (in Italian). Arbitalia. Retrieved 2 February 2017.

- "RIONERO IN VULTURE (Basilicata / Lucania) – Fotografie". lucania1.altervista.org. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- Euromosaic. Albanian in Italy.

- Albanian literature: a short history Authors Robert Elsie, Centre for Albanian Studies (London, England) Publisher I.B. Tauris, 2005 ISBN 1-84511-031-5, ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4 p. 45

- Albanian literature: a short history Authors Robert Elsie, Centre for Albanian Studies (London, England) Publisher I.B.Tauris, 2005 ISBN 1-84511-031-5, ISBN 978-1-84511-031-4 p. 46-47

- Skendi, Stavro (1968). "Skenderbeg and Albanian Consciousness". Südost Forschungen. 27: 83–84. "The memory of the Albanian national hero was maintained vividly among the Albanians of Italy, those who emigrated to Calabria and Sicily, following his death.... Living compactly in Christian territory, though in separate communities, the Italo-Albanians have preserved the songs about Skenderbeg and his exploits which their ancestors had brought from the mother country. Today one may even speak of the existence of a Skenderbeg cycle among them, if one takes into account also the songs on other Albanian heroes who surrounded him."

- MASCI, L.F. Gli insediamenti Albanesi in Italia (Morfologia e Architettura), Nuclei Urbani della Calabria Citra. Comune di S. Sofia D'Epiro 2004

- A SKETCH OF THE ANTHROPOLOGY OF ITALY.By V. GlUFFRIDA-RUGGERI, PROFESSOR OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN THE UNIVERSITYOF NAPLES.

- Sarno, Stefania (16 May 2017). "Ancient and recent admixture layers in Sicily and Southern Italy trace multiple migration routes along the Mediterranean". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 1984. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.1984S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01802-4. PMC 5434004. PMID 28512355. S2CID 669567.

- Sarno, Stefania (16 May 2017). "Ancient and recent admixture layers in Sicily and Southern Italy trace multiple migration routes along the Mediterranean". Scientific Reports. 7 (1): 1984. Bibcode:2017NatSR...7.1984S. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-01802-4. PMC 5434004. PMID 28512355. S2CID 669567.

External links

- Arbitalia Shtëpia e Arbëreshëvet të Italisë / The Home of Albanians of Italy

- Jemi.it the Arbëresh web portal managed by the Eparchy of Lungro

- Jeta Arbëreshe Bilingual magazine

- Arberiaguzzardi Maps of the Albanians of Italy

- Mondoarberesco.it Web Jeta Arbresh

- Museoetnicoarbresh.org Albanian Ethnic Museum of Civita

- Vatrarberesh.it The Albanian Fire

- Arbelmo.it The Italo-Albanian sociocultural blog

- Scesci i Pasionatit.it

- Katundiyne.com Magazine Katundi Yne - Paese Nostro

- E-biblía Digital library on the faith and knowledge of the Italo-Albanian people

- Unibesa.it BESA - Union of Albanian Municipalities of Sicily

- Unical.it Università della Calabria - Laboratorio di Albanologia

- Treccani.it La comunità albanese d'Italia su Enciclopedia Treccani

- Albanian, Arbëreshë in Ethnologue Languages of the World

- "Shared language, diverging genetic histories: high-resolution analysis of Y-chromosome variability in Calabrian and Sicilian Arbereshe". European Journal of Human Genetics. 2016.

_-_Paesaggio.jpg.webp)