European Portuguese

European Portuguese (Portuguese: português europeu, pronounced [puɾtuˈɣez ewɾuˈpew]) also known as Portuguese of Portugal (Portuguese: português de Portugal), Iberian Portuguese (Portuguese: português ibérico), Peninsular Portuguese (Portuguese: português peninsular) refers to the Portuguese language spoken in Portugal. The word “European” was chosen to avoid the clash of “Portuguese Portuguese” (“português português”) as opposed to Brazilian Portuguese.

| European Portuguese | |

|---|---|

| Português europeu | |

| Native to | Portugal |

Native speakers | 40 million (2012)[1] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

| IETF | pt-PT |

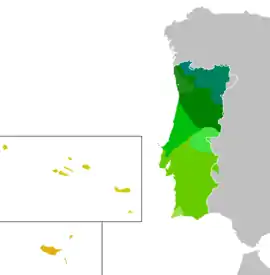

Dialectical continuum of Iberian Romance languages including European Portuguese and its dialects. | |

Portuguese is a pluricentric language, i.e., it is the same language with several interacting codified standard forms in many countries. Portuguese is a Latin based language, with Celtic, Germanic, Greek and Arabic influence. It was spoken in the Iberian Peninsula before as Galician-Portuguese. With the formation of Portugal as a country in the 12th century, the language evolved into Portuguese. In the Spanish province of Galicia, Northern border of Portugal, the native language is Galician. Both Portuguese and Galician are very similar and natives can understand each other as they share the same recent common ancestor. Portuguese and Spanish are different languages, although they share 89% of their lexicon.[2]

Phonology

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Vowel classification

Portuguese uses vowel height to contrast stressed syllables with unstressed syllables; the vowels /a ɛ e ɔ o/ tend to be raised to [ɐ ɛ ɨ ɔ u] when they are unstressed (see below for details). The dialects of Portugal are characterized by reducing vowels to a greater extent than others. Falling diphthongs are composed of a vowel followed by one of the high vowels /i/ or /u/; although rising diphthongs occur in the language as well, they can be interpreted as hiatuses.

European Portuguese possesses quite a wide range of vowel allophones:

- All vowels are lowered and retracted before /l/.[3]

- All vowels are raised and advanced before alveolar, palato-alveolar and palatal consonants.[3]

- Word-finally, /ɨ/ as well as unstressed /u/ and /ɐ/ are voiceless [ɯ̥̽, u̥, ə̥].[3]

The realization of /ɐ/ this contrast occurs in a limited morphological context, namely in verbs conjugation between the first person plural present and past perfect indicative forms of verbs such as pensamos ('we think') and pensámos ('we thought').[4][5] proposes that it is a kind of crasis rather than phonemic distinction of /a/ and /ɐ/. It means that in falamos 'we speak' there is the expected prenasal /a/-raising: [fɐˈlɐmuʃ], while in falámos 'we spoke' there are phonologically two /a/ in crasis: /faˈlaamos/ > [fɐˈlamuʃ]. Close-mid vowels and open-mid vowels (/e ~ ɛ/ and /o ~ ɔ/) contrast only when they are stressed.[6] In unstressed syllables, they occur in complementary distribution.

According to Mateus and d'Andrade (2000:19),[7] in European Portuguese, the stressed [ɐ] only occurs in the following three contexts:

- Before a palatal consonant (such as telha [ˈtɐʎɐ])

- Before the palatal front glide (such as lei [ˈlɐj])

- Before a nasal consonant (such as cama [ˈkɐmɐ])

In Greater Lisbon (according to NUTS III, which does not include Setúbal) /e/ can be centralized [ɐ] before palatal sounds (/j, ɲ, ʃ, ʒ, ʎ/); e.g. roupeiro [ʁoˈpɐjɾu], brenha [ˈbɾɐ(ʲ)ɲɐ], texto [ˈtɐ(ʲ)ʃtu], vejo [ˈvɐ(ʲ)ʒu], coelho [kuˈɐ(ʲ)ʎu].

European Portuguese "e caduc"

European Portuguese possesses a near-close near-back unrounded vowel. It occurs in unstressed syllables such as in pegar [pɯ̽ˈɣaɾ] ('to grip').[3] There is no standard symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet for this sound. The IPA Handbook transcribes it as /ɯ/, but in Portuguese studies /ɨ/ is traditionally used.[8]

- Traditionally, it is pronounced when "e" is unstressed; e.g. verdade [vɨɾˈðaðɨ], perigo [pɨˈɾiɣu].

- However, if "e" is initial, then it is pronounced [i]; e.g. energia [inɨɾˈʒiɐ], exemplo [iˈzẽplu].

- When "e" is surrounded by another vowel, it becomes [i]; e.g. real [ʁiˈal].

- However, notice that when the e caduc is preceded by a semi-vowel, it may become [e ~ ɛ] poesia [puɛˈziɐ], quietude [kjɛˈtuðɨ].

- Theoretically, unstressed "i" cannot be lowered to /ɨ/. However, when it is surrounded by [i, ĩ] or any palatal sound [ɲ, ʎ, ʃ, ʒ], it usually becomes /ɨ/. E.g. ministro [mɨˈniʃtɾu], príncipe [ˈpɾĩsɨpɨ], artilhar [ɐɾtɨˈʎaɾ], caminhar [kɐmɨˈɲaɾ], pistola [pɨʃˈtɔlɐ], pijama [pɨˈʒɐmɐ].

- The Portuguese e caduc may be elided, becoming in some instances a syllabic consonant; e.g. verdade [vɾ̩ˈðað], perigo [ˈpɾiɣu], energia, [inɾ̩ˈʒiɐ], ministro [mˈniʃtɾu], príncipe [ˈpɾĩsp], artilhar [ɐɾtˈʎaɾ], caminhar [kɐmˈɲaɾ], pistola [pʃ̩ˈtɔlɐ].

There are very few minimal pairs for this sound: some examples include pregar [pɾɨˈɣaɾ] ('to nail') vs. pregar [pɾɛˈɣaɾ] ('to preach'; the latter stemming from earlier preegar < Latin praedicāre),[9] sê [ˈse] ('be!') vs. sé [ˈsɛ] ('see/cathedral') vs. se [sɨ] ('if'), and pêlo [ˈpelu] ('hair') vs. pélo [ˈpɛlu] ('I peel off') vs. pelo [pɨlu] ('for the'),[10] after orthographic changes, all these three words are now spelled pelo.

Geographic variation

European Portuguese is divided into Northern and Southern varieties. The prestige norms are based on two varieties: that of Coimbra and that of Lisbon.[11][12]

Phonetically, differences emerge within Continental Portuguese. For example, in northern Portugal, the phonemes /b/ and /v/ are less differentiated than in the rest of the Portuguese speaking world (similar to the other languages of the Iberian peninsula). Also, the original alveolar trill remains common in many northern dialects (especially in rural areas), like Transmontano, Portuense, Minhoto, and much of Beirão. Another regionalism can be found in the south and the islands with the use of the gerund in the present progressive tense rather than the infinitive.

Portuguese is spoken by a significant minority in Andorra and Luxembourg. The Principality of Andorra has shown interest in membership in the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP). There are also immigrant communities in France and Germany.

Galician

The Galician language, spoken in the Autonomous Community of Galicia in Spain, is very closely related to Portuguese. There is, as yet, no consensus among writers and linguists on whether Galician and Portuguese are still the same language (in fact they were for many centuries, Galician-Portuguese having developed in the region of the former Roman province of Gallaecia, from the Vulgar Latin that had been introduced by Roman soldiers, colonists and magistrates during the time of the Roman Empire) or distinct yet closely related languages.

Galicia has expressed interest in joining the CPLP as an associate observer pending permission from the Spanish government.

Prominence

The Instituto Camões is a Portuguese international institution dedicated to the worldwide promotion of the Portuguese language, Portuguese culture, and international aid, on behalf of the Government of Portugal.

RTP is the Portuguese public television network and also serves as a vehicle for European-Portuguese-providing media content throughout the world. There is a branch of RTP Internacional named RTP África, which serves Lusophone Africa.

In estimating the size of the speech community for European Portuguese, one must take into account the consequences of the Portuguese diaspora: immigrant communities located throughout the world in the Americas, Australia, Europe and Africa.

References

- Portuguese at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- Urban Multilingualism in Europe: Immigrant Minority Languages at Home and School. Guus Extra, Kutlay Yaǧmur. Multilingual Matters, 2004. 428p., ISBN 9781853597787

- Cruz-Ferreira (1995:92)

- http://www.uel.br/revistas/uel/index.php/signum/article/viewFile/3881/3120

- Spahr (2013:6)

- Major (1972:7)

- Mateus and d'Andrade (2000). The Phonology of Portuguese. Oxford University Press. p. 19.

- https://european-portuguese.info/pt/vowels

- Harris, Martin; Vincent, Nigel (1988), The Romance Languages, Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Mateus, Maria Helena Mira; Brito, Ana Maria; Duarte, Inês; Faria, Isabel Hub (2003), Gramática da Língua Portuguesa, colecção universitária, Linguística (in Portuguese) (7 ed.), Lisbon: Caminho, p. 995, ISBN 972-21-0445-4

- Baxter, A. N. Portuguese as a Pluricentric Language.

- Clyne, Michael G. Pluricentric languages. p. 14.