African Romance

African Romance or African Latin is an extinct Romance language that was spoken in the Roman province of Africa by the Roman Africans during the later Roman and early Byzantine Empires, and several centuries after the annexation of the region by the Umayyad Caliphate in 696 AD. African Romance is poorly attested as it was mainly a spoken, vernacular language, a sermo rusticus.[1] There is little doubt, however, that by the early 3rd century AD, some native provincial variety of Latin was fully established in Africa.[2]

| African Romance | |

|---|---|

| Region | Diocese of Africa / Ifriqiya |

| Ethnicity | Roman Africans |

| Era | Classical Antiquity, Middle Ages (c. 1st century BC – 14th century) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | None (mis) |

lat-afr | |

| Glottolog | None |

This language, which developed under Byzantine rule, continued through to the 12th century in various places along the North African coast and the immediate littoral,[1] with evidence that it may have persisted up to the 14th century,[3] and possibly even the 15th century,[2] or later[3] in certain areas of the interior. It was, along with the region's other languages such as Berber, subsequently suppressed and supplanted by Arabic after the Arab conquest of the Maghreb.

Background

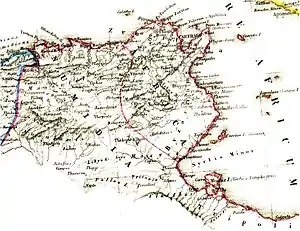

The Roman province of Africa was organized in 146 BC following the defeat of Carthage in the Third Punic War. The city of Carthage, destroyed following the war, was rebuilt during the dictatorship of Julius Caesar as a Roman colony, and by the 1st century, it had grown to be the fourth largest city of the empire, with a population in excess of 100,000 people.[upper-alpha 1] The Fossa regia was an important boundary in North Africa, originally separating the Roman occupied Carthaginian territory from Numidia,[5] and may have served as a cultural boundary indicating Romanization.[6]

In the time of the Roman Empire, the province had become populous and prosperous, and Carthage was the second-largest Latin-speaking city in the Empire. Latin was, however, largely an urban and coastal speech. Carthaginian Punic continued to be spoken in inland and rural areas as late as the mid-5th century, but also in the cities.[7] It is probable that Berber languages were spoken in some areas as well.

Funerary stelae chronicle the Romanization of art and religion in North Africa.[8] Notable differences, however, existed in the penetration and survival of the Latin, Punic and Berber languages.[9] These indicated regional differences: Neo-Punic had a revival in Tripolitania, around Hippo Regius there is a cluster of Libyan inscriptions, while in the mountainous regions of Kabylie and Aures, Latin was scarcer, though not absent.[9]

Africa was occupied by the Germanic Vandal tribe for over a century, between 429 and 534 AD, when the province was reconquered by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I. The changes that occurred in spoken Latin during that time are unknown. Literary Latin, however, was maintained at a high standard, as seen in the Latin poetry of the African writer Corippus. The area around Carthage remained fully Latin-speaking until the arrival of the Arabs.

Origins and development

Like all Romance languages, African Romance descended from Vulgar Latin, the non-standard (in contrast to Classical Latin) form of the Latin language, which was spoken by soldiers and merchants throughout the Roman Empire. With the expansion of the empire, Vulgar Latin came to be spoken by inhabitants of the various Roman-controlled territories in North Africa. Latin and its descendants were spoken in the Province of Africa following the Punic Wars, when the Romans conquered the territory. Spoken Latin, and Latin inscriptions developed while Punic was still being used.[10] Bilingual inscriptions were engraved, some of which reflect the introduction of Roman institutions into Africa, using new Punic expressions.[10]

Latin, and then some Romance variant of it, was spoken by generations of speakers, for about fifteen centuries.[2] This was demonstrated by African-born speakers of African Romance who continued to create Latin inscriptions until the first half of the 11th century.[2] Evidence for a spoken Romance variety which developed locally out of Latin persisted in rural areas of Tunisia - possibly as late as the last two decades of the 15th century in some sources.[11]

By the late 19th century and early 20th century, the possible existence of African Latin was controversial,[12] with debates on the existence of Africitas as a putative African dialect of Latin. In 1882, the German scholar Karl Sittl used unconvincing material to adduce features particular to Latin in Africa.[12] This unconvincing evidence was attacked by Wilhelm Kroll in 1897,[13] and again by Madeline D. Brock in 1911.[14] Brock went so far as to assert that "African Latin was free from provincialism",[15] and that African Latin was "the Latin of an epoch rather than that of a country".[16] This view shifted in recent decades, with modern philologists going so far as to say that African Latin "was not free from provincialism"[17] and that, given the remoteness of parts of Africa, there were "probably a plurality of varieties of Latin, rather than a single African Latin".[17] Other researchers believe that features peculiar to African Latin existed, but are "not to be found where Sittl looked for it".[17]

While as a language African Romance is extinct, there is some evidence of regional varieties in African Latin that helps reconstruct some of its features.[18] Some historical evidence on the phonetic and lexical features of the Afri were already observed in ancient times. Pliny observes how walls in Africa and Spain are called formacei, or "framed walls, because they are made by packing in a frame enclosed between two boards, one on each side".[19] Nonius Marcellus, a Roman grammarian, provides further, if uncertain, evidence regarding vocabulary and possible "Africanisms".[20][upper-alpha 2] In the Historia Augusta, the North African Roman Emperor Septimius Severus is said to have retained an African accent until old age.[upper-alpha 3] More recent analysis focuses on a body of literary texts, being literary pieces written by African and non-African writers.[23] These show the existence of an African pronunciation of Latin, then moving on to a further study of lexical material drawn from sub-literary sources, such as practical texts and ostraca, from multiple African communities, that is military writers, landholders and doctors.[23]

Adams lists a number of possible Africanisms found in this wider Latin literary corpus.[24] Only two refer to constructions found in Sittl,[25] with the other examples deriving from medical texts,[26] various ostraca and other non-traditional sources. Two sorts of regional features can be observed. The first are loanwords from a substrate language, such is the case with Britain. In African Latin, this substrate was Punic. African Romance included words such as ginga for "henbane", boba for "mallow," girba for "mortar" and gelela for the inner flesh of a gourd.[27] The second refers to use of Latin words with particular meanings not found elsewhere, or in limited contexts. Of particular note is the African Romance use of the word rostrum for "mouth" instead of the original meaning in Latin, which is "beak",[28] and baiae for "baths" being a late Latin and particularly African generalisation from the place-name Baiae.[29] Pullus meaning "cock" or "rooster", was probably borrowed by Berber dialects from African Romance, for use instead of the Latin gallus.[30] The originally abstract word dulcor is seen applied as a probable medical African specialisation relating to sweet wine instead of the Latin passum or mustum.[31] The Latin for grape, traditionally indeterminate (acinis), male (acinus) or neuter (acinum), in various African Latin sources changes to the feminine acina.[32] Other examples include the use of pala as a metaphor for the shoulder blade; centenarium, which only occurs in the Albertini Tablets and may have meant "granary";[33] and infantilisms such as dida.[34]

Both Africans, such as Augustine of Hippo and the grammarian Pompeius, as well as non-Africans, such as Consentius and Jerome, wrote on African features, some in very specific terms.[35] Indeed in his De Ordine, dated to late 386, Augustine remarks how he was still "criticised by the Italians" for his pronunciation, while he himself often found fault with theirs.[36] While modern scholars may express doubts on the interpretation or accuracy of some of these writings, they contend that African Latin must have been distinctive enough to inspire so much discussion.[37]

Extinction as a vernacular

Following the Arab conquest in 696–705 AD, it is difficult to trace the fate of African Romance, though it was soon replaced by Arabic as the primary administrative language. It is not known when African Latin ceased to be spoken in North Africa, but it is likely that it continued to be widely spoken in various parts of the littoral of Africa into the 12th century. [1]

At the time of the conquest a Romance language was probably spoken in the cities and Berber languages were also spoken in the region.[38] Loanwords from Northwest African Romance to Berber are attested and are usually in the accusative form: examples include atmun ("plough-beam") from temonem.[38] It is unclear for how long Romance continued to be spoken, but its influence on Northwest African Arabic (particularly in the language of northwestern Morocco) indicates it must have had a significant presence in the early years after the Arab conquest.[38]

Spoken Latin or Romance is attested in Gabès by Ibn Khordadbeh, in Béja, Biskra, Tlemcen and Niffis by al-Bakri and in Gafsa and Monastir by al-Idrisi.[1] The latter describes how the people in Gafsa "are Berberised, and most of them speak the African Latin tongue."[1][39][upper-alpha 4]

In their pursuit of acquiring their African kingdom in the 12th century, the Normans received help from the remaining Christian population of Tunisia, and some linguists such as Vermondo Brugnatelli argue that those Christians had been speaking a Romance language for centuries.[40] The language existed until the arrival of the Banu Hilal Arabs in the 11th century and probably until the beginning of the fourteenth century.[41]

Furthermore, modern scholars have identified that, amongst the Berbers of Afrikiya, the African Romance language was linked to Christianity, which survived in North Africa until the 14th century.[3] According to the testimony of Mawlâ Aḥmad, a Romance dialect probably survived in Touzeur (south of Gafsa, Tunisia) until the early 18th century.[3] Indeed in 1709, Ahmad wrote that "the inhabitants of Touzeur are a remnant of the Christians who were once in Afrikiya, before the Arab conquest".[upper-alpha 5]

Related languages

Sardinian

| Extract from the Sardinian text sa Vitta et sa Morte, et Passione de sanctu Gavinu, Prothu et Januariu (A. Cano, ~1400)[43] |

|---|

| O

Deus eternu, sempre omnipotente, |

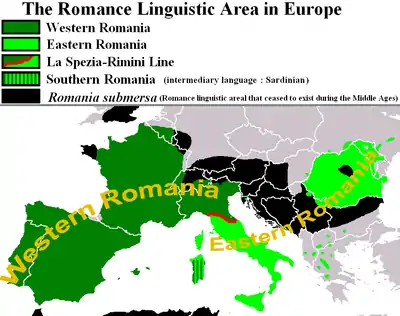

The spoken variety of African Romance, as recorded by Paolo Pompilio, was perceived to be similar to Sardinian[upper-alpha 6] – confirming hypotheses that there were parallelisms between developments of Latin in Africa and Sardinia.[11] In fact, some linguists, like the philologist Heinrich Lausberg, proposed to classify Sardinian as the sole living representative of a Southern group of the Romance languages, which once also comprised the African Latin dialects, as well as the Corsican dialects spoken prior to the island's Tuscanization.

Augustine of Hippo writes that "African ears have no quick perception of the shortness or length of [Latin] vowels".[45][46][upper-alpha 7] This also describes the evolution of vowels in the Sardinian language. Sardinian has only five vowels, and no diphthongs: unlike some other surviving Romance languages, the five long and short vowel pairs of classical Latin (a/ā, e/ē, i/ī, o/ō, u/ū) merged into five single vowels with no length distinction (a, e, i, o, u).[upper-alpha 8] Italian and Romanian have seven, while Portuguese and Catalan have eight.

Adams theorises that similarities in some vocabulary, such as spanu[48] in Sardinian and spanus in African Romance ("light red") may be evidence that some vocabulary was shared between Sardinia and Africa.[49] A further theory suggests that the Sardinian word for "Friday", cenàpura or chenàpura,[50] may have been brought to Sardinia from Africa by Jews from North Africa.[51]

Muhammad al-Idrisi also says of the island's native people that "the Sardinians are ethnically[52] Roman Africans, live like the Berbers, shun any other nation of Rûm; these people are courageous and valiant, that never part with their weapons."[53][54][upper-alpha 9]

Other languages

Some impacts of African Romance on Arabic spoken in the Maghreb are also theorised.[56] For example, in calendar month names, the word furar "February" is only found in the Maghreb and in the Maltese language - proving the word's ancient origins.[56] The region also has a form of another Latin named month in awi/ussu < augustus.[56] This word does not appear to be a loan word through Arabic, and may have been taken over directly from Late Latin or African Romance.[56] Scholars theorise that a Latin-based system provided forms such as awi/ussu and furar, with the system then mediating Latin/Romance names through Arabic for some month names during the Islamic period.[57] The same situation exists for Maltese which mediated words from Italian, and retains both non-Italian forms such as awissu/awwissu and frar, and Italian forms such as april.[57]

Some scholars theorise that many of the North African invaders of Hispania in the Early Middle Ages spoke some form of African Romance, with "phonetic, morphosyntactic, lexical and semantic data" from African Romance appearing to have contributed in the development of Ibero-Romance.[58]

Brugnatelli pinpoints some Berber words, relating to religious topics, as being originally words from Latin: for example, in Ghadames the word "äng'alus" (ⴰⵏⵖⴰⵍⵓⵙ, أنغلس) refers to a spiritual entity, clearly using a word from the Latin angelus "angel".[59][60]

Characteristics

Starting from African Romance's similarity with Sardinian, scholars theorise that the similarity may be pinned down to specific phonological properties.[11] Sardinian lacks palatization of velar stops before front vowels, and features the pairwise merger of short and long non-low vowels.[2] Evidence is found that both isoglosses were present in African Latin:

- Velar stops remain unaffected in Latin loanwords in Berber.[2] For example, tkilsit "mulberry tree" < (morus) celsa in Latin,[61] and i-kīkər "chickpea" < cicer in Latin,[62] or ig(e)r ,"field" ager in Latin.[63]

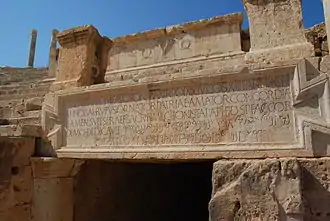

- Inscriptions from Tripolitania, written as late as the 10th or 11th century are written with a <k>, diverging from contemporary European Latin uses.[64] Thus, there are forms such as dikite and iaket, with <k> such as dilektus "beloved" and karus "dear", found in an inscriptional corpus.[65]

- Some evidence that Latin words with a <v> are often written with a <b> in African Romance, as reported by Isidore of Seville: birtus "virtue" < virtus in Latin, boluntas "will" < voluntas, and bita "life" < vita.[upper-alpha 10]

- The Albertini Tablets suggest high levels of phonetic errors and an uncertainty in the use of Latin cases.[67]

- In ostraca from Bu Njem, there is evidence of significant number of errors and deviations from Classical Latin, such as the omission of the final -m in numerous endings after -a (being often misspelled accusatives). There is evidence of the e-spelling for <æ>, which is unaccompanied by evidence of merging <ē> and <ǐ> or <ō> and <ŭ>, the elimination by various strategies of vowels in hiatus,[68] as well as to a lesser extent the change of the short Latin <û> to a close <ọ>, and the retention of the -u spelling is kept in second declension words.[69]

There also is evidence that the vowel system of African Latin was similar to Sardinian.[64][70] Augustine of Hippo's testimony on how ōs "mouth" in Latin was to African ears indistinguishable from ŏs "bone" indicates the merger of vowels and the loss of the original allophonic quality distinction in vowels.[71][upper-alpha 11]

Moreover, in a study of errors on stressed vowels in a corpus of 279 inscriptions, scholars noted how African inscriptions confused between over-stressed and under-stressed vowels between the 1st and 4th century AD, with Rome reaching comparable error rates only by the late 4th to 6th centuries.[72]

Berber vocabulary

The Polish Arabist Tadeusz Lewicki tried to reconstruct some sections of this language based on 85 lemmas mainly derived from Northwest African toponyms and anthroponyms found in medieval sources.[73] Due to the historical presence in the region of Classical Latin, modern Romance languages, as well as the influence of the Mediterranean Lingua Franca (that has Romance vocabulary) it is difficult to differentiate the precise origin of words in Berber languages and in the varieties of Maghrebi Arabic. The studies are also difficult and often highly conjectural. Due to the large size of the North African territory, it is highly probable that not one but several varieties of African Romance existed, much like the wide variety of Romance languages in Europe.[74] Moroever, other Romance languages spoken in Northwest Africa before the European colonization were the Mediterranean Lingua Franca,[75] a pidgin with Arabic and Romance influences, and Judaeo-Spanish, a dialect of Spanish brought by Sephardi Jews.[76]

Scholars believe that there is a great number of Berber words, existing in various dialects, which are theorised to derive from late Latin or African Romance, such as:

| English | Berber | Latin | Italian |

| sin | abekkadu[77] | peccatum | peccato |

| oven | afarnu[78] | furnus | forno |

| oak | akarruš / akerruš [79][80] | cerrus, quercius (?) | quercio |

| oleander | alili / ilili / talilit [81][82] | lilium | oleandro |

| flour | aren [83] | farina | farina |

| large sack | asaku [84][85] | saccus | grosso sacco |

| helm | atmun [86][63] | temo | timone |

| August | awussu[87] | augustus | agosto |

| blite | blitu [88] | blitum | pera mezza |

| young boy | bušil[89] | pusillus | fanciullo |

| large wooden bowl | dusku[90][91] | discus | grossa scodella in legno |

| locality in Tripolitania | Fassaṭo[92] | fossatum (?) | località della Tripolitania |

| February | furar[93] | forar | febbraio |

| castle / village | ġasru[94] | castrum | castello / borgo/ villaggio |

| bean | ibaw[95][96] | faba | fava |

| horehound | immerwi[97] | marrubium | marrubio |

| cultivated field | iger / ižer [98] | ager | campo coltivato |

| chickpea | ikiker[62] | cicer | cece |

| durmast | iskir [99][100] | aesculus | rovere |

| cat | qaṭṭus[101] | cattus | gatto |

| locality in Morocco | Rif[92] | ripa (?) | località del Marocco |

| throat | tageržumt[102] | gorgia | gola |

See also

- British Latin, another extinct dialect of Latin.

- Moselle Romance, another extinct dialect of Latin.

- Pannonian Romance, another extinct dialect of Latin.

Notes

- Likely the fourth city in terms of population during the imperial period, following Rome, Alexandria and Antioch, in the 4th century also surpassed by Constantinople; also of comparable size were Ephesus, Smyrna and Pergamum.[4]

- Most of the Africanisms mentioned by Nonius, as listed in Contini (1987) do not bear up to more modern analysis.[21]

- Latin: "...canorus voce, sed Afrum quiddam usque ad senectutem sonans." [22]

- Arabic: "وأهلها متبربرون وأكثرهم يتكلّم باللسان اللطيني الإفريقي"

wa-ahluhum mutabarbirūn wa-aktharuhum yatakallam bil-lisān al-laṭīnī al-ifrīqī [39] - French: "les gens de Touzeur sont un reste des chrétiens qui étaient autrefois en Afrik’ïa, avant que les musulmans en fissent la conquête"[42]

- Latin: «ubi pagani integra pene latinitate loquuntur et, ubi uoces latinae franguntur, tum in sonum tractusque transeunt sardinensis sermonis, qui, ut ipse noui, etiam ex latino est» ("where villagers speak an almost intact Latin and, when Latin words are corrupted, then they pass to the sound and habits of the Sardinian language, which, as I myself know, also comes from Latin")[44]

- Latin: «Afrae aures de correptione vocalium vel productione non iudicant» ("African ears show no judgement in the matter of the shortening of vowels or their lengthening")[45]

- German: "Es wäre auch möglich, daß die Sarden die lat. Quantitäten von vornherein nicht recht unterschieden." ("It is likely that the Sardinians had never differentiated well from the beginning the Latin quantities.")[47]

- Arabic: وأهل جزيرة سردانية في أصل روم أفارقة متبربرون متوحشون من أجناس الروم وهم أهل نجدة وهزم لا يفرقون السلاح

(Wa ahl Ğazīrat Sardāniya fī aṣl Rūm Afāriqa mutabarbirūn mutawaḥḥišūn min ağnās ar-Rūm wa hum ahl nağida wa hazm lā yufariqūn as-silāḥ.) [55] - Latin: "Birtus, boluntas, bita vel his similia, quæ Afri scribendo vitiant..." [66]

- Latin: "cur pietatis doctorem pigeat imperitis loquentem ossum potius quam os dicere, ne ista syllaba non ab eo, quod sunt ossa, sed ab eo, quod sunt ora, intellegatur, ubi Afrae aures de correptione uocalium uel productione non iudicant?" (Why should a teacher of piety when speaking to the uneducated have regrets about saying ossum ("bone") rather than os in order to prevent that monosyllable (i.e. ŏs "bone") from being interpreted as the word whose plural is ora (i.e. ōs "mouth") rather than the word whose plural is ossa (i.e. ŏs), given that African ears show no judgement in the matter of the shortening of vowels or their lengthening?)[45][46]

References

Citations

- Scales 1993, pp. 146 - 147.

- Loporcaro 2015, p. 47.

- Prevost 2007, pp. 461 - 483.

- Brunn, Hays-Mitchell & Zeigler 2012, p. 27.

- Ferchiou 1998, p. 2.

- Guédon 2018, p. 37.

- Adams 2003, p. 213.

- Varner 1990, p. 16.

- Whittaker 2009, pp. 193-194.

- Chatonnet & Hawley 2020, pp. 305-306.

- Loporcaro 2015, p. 48.

- Adams 2007, p. 516.

- Kroll 1897, pp. 569 - 590.

- Brock 1911, pp. 161–261.

- Brock 1911, p. 257.

- Brock 1911, p. 261.

- Matiacci 2014, p. 92.

- Galdi 2011, pp. 571–573.

- Pliny the Younger, p. XLVIII.

- Adams 2007, pp. 546–549.

- Adams 2007, p. 546.

- Anonymous, p. 19.9.

- Matiacci 2014, pp. 87–93.

- Adams 2007, pp. 519 - 549.

- Adams 2007, pp. 519–520.

- Adams 2007, pp. 528 - 542.

- Galdi 2011, p. 572.

- Adams 2007, p. 543.

- Adams 2007, p. 534.

- Adams 2007, p. 544.

- Adams 2007, p. 535.

- Adams 2007, p. 536.

- Adams 2007, p. 553.

- Adams 2007, p. 541.

- Adams 2007, p. 269.

- Adams 2007, pp. 192-193.

- Adams 2007, p. 270.

- Haspelmath & Tadmor 2009, p. 195.

- al-Idrisi 1154, pp. 104-105.

- Brugnatelli 1999, pp. 325 - 332.

- Rushworth 2004, p. 94.

- Prevost 2007, p. 477.

- Cano 2002, p. 3.

- Charlet 1993, p. 243.

- Adams 2007, p. 261.

- Augustine of Hippo, p. 4.10.24.

- Lausberg 1956, p. 146.

- Rubattu 2006, p. 433.

- Adams 2007, p. 569.

- Rubattu 2006, p. 810.

- Adams 2007, p. 566.

- Translation provided by Michele Amari: «I sardi sono di schiatta RUM AFARIQAH (latina d'Africa), berberizzanti. Rifuggono (dal consorzio) di ogni altra nazione di RUM: sono gente di proposito e valorosa, che non lascia mai l'arme.» Note to the passage by Mohamed Mustafa Bazama: «Questo passo, nel testo arabo, è un poco differente, traduco qui testualmente: "gli abitanti della Sardegna, in origine sono dei Rum Afariqah, berberizzanti, indomabili. Sono una (razza a sé) delle razze dei Rum. [...] Sono pronti al richiamo d'aiuto, combattenti, decisivi e mai si separano dalle loro armi (intende guerrieri nati).» Mohamed Mustafa Bazama (1988). Arabi e sardi nel Medioevo. Cagliari: Editrice democratica sarda. pp. 17, 162.

- Mastino 2005, p. 83.

- Contu 2005, pp. 287-297.

- Contu 2005, p. 292.

- Kossmann 2013, p. 75.

- Kossmann 2013, p. 76.

- Wright 2012, p. 33.

- Kossmann 2013, p. 81.

- Brugnatelli 2001, p. 170.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 22.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 24.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 50.

- Loporcaro 2015, p. 49.

- Lorenzetti & Schirru 2010, p. 311.

- Monceaux 2009, p. 104.

- Adams 2007, p. 549.

- Adams 1994, p. 111.

- Adams 1994, p. 94.

- Adams 2007, p. 262.

- Loporcaro 2011, p. 113.

- Loporcaro 2011, pp. 56 - 57.

- Lewicki 1958, pp. 415-480.

- Fanciullo 1992, p. 162-187.

- Martínez Díaz 2008, p. 225.

- Kirschen 2015, p. 43.

- Dallet 1982, p. 20.

- Dallet 1982, p. 225.

- Dallet 1982, p. 416.

- Schuchardt 1918, pp. 18 - 19.

- Dallet 1982, p. 441.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 26.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 54.

- Dallet 1982, p. 766.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 59.

- Dallet 1982, p. 825.

- Paradisi 1964, p. 415.

- Dallet 1982, p. 26.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 42.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 56.

- Beguinot 1942, p. 280.

- Mastino 1990, p. 321.

- Dallet 1982, p. 219.

- Beguinot 1942, p. 297.

- Dallet 1982, p. 57.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 23.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 25.

- Dallet 1982, p. 270.

- Dallet 1982, pp. 86 - 87.

- Schuchardt 1918, pp. 16 - 17.

- Beguinot 1942, p. 235.

- Schuchardt 1918, p. 45.

Primary sources

- al-Idrisi, Abu Abdullah Muhammad al-Qurtubi al-Hasani as-Sabti (1154). Nuzhat al-mushtāq fi'khtirāq al-āfāq [The book of pleasant journeys into faraway lands]. pp. 104–105.

- Augustine of Hippo. On Christian Doctrine Book IV Cap 10:24 – via Wikisource.

- Cano, Antonio (2002). Manca, Dino (ed.). sa Vitta et sa Morte, et Passione de sanctu Gavinu, Prothu et Januariu (PDF). p. 3.

- Anonymous. Historia Augusta 19.9 – via Wikisource.

- Pliny the Younger. Natural History XXXV. – via Wikisource.

Secondary sources

- Adams, J.N. (1994). "Latin and Punic in Contact? The Case of the bu Njem Ostraca". The Journal of Roman Studies. Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. 84: 87–112. doi:10.2307/300871. JSTOR 300871.

- Adams, J.N. (2003). Bilingualism and the Latin Language. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521817714.

- Adams, J.N. (2007). The Regional Diversification of Latin 200 BC - AD 600. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1139468817.

- Bazama, Mohamed Mustafa (1988). Arabi e sardi nel Medioevo (in Italian). Cagliari: Editrice democratica sarda.

- Beguinot, F. (1942). Il Berbero Nefusi di Fassato (in Italian). Roma.

- Brock, Madeline D. (1911). Studies in Fronto and His Age: With an Appendix on African Latinity Illustrated by Selections from the Correspondence of Fronto. Girton College studies. Cambridge: University Press.

- Brugnatelli, Vermondo (1999). Lamberti, Marcello; Tonelli, Livia (eds.). I prestiti latini in berbero: un bilancio. Afroasiatica Tergestina. Papers from the 9th Italian Meeting of Afro-Asiatic (Hamito-Semitic) Linguistics, Trieste, April 23–24, 1998. (in Italian). Padua: Unipress.

- Brugnatelli, Vermondo (2001). Il berbero di Jerba: secondo rapporto preliminare. Incontri Linguistici (in Italian). 23. Università degli Studi di Udine e di Trieste. pp. 169–182.

- Brunn, Stanley; Hays-Mitchell, Maureen; Zeigler, Donald J., eds. (2012). Cities of the World: World Regional Urban Development. Reference, Information and Interdisciplinary Subjects Series. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 9781442212848.

- Charlet, J.L. (1993). "Un témoignage humaniste sur la latinité africaine et le grec parlé par les 'Choriates' : Paolo Pompilio". Antiquités Africaines (in French). 29: 241–247. doi:10.3406/antaf.1993.1220.

- Chatonnet, Françoise Briquel; Hawley, Robert (2020). Hasselbach-Andee, Rebecca (ed.). A Companion to Ancient Near Eastern Language. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 9781119193296.

- Contini, A.M.V. (1987). "Nonio Marcello e l'Africitas". Studi noniani (in Italian). 12: 17–26.

- Contu, Giuseppe (2005). "Sardinia in Arabic sources" (PDF). Annali della Facoltà di Lingue e Letterature Straniere dell'Università di Sassari. 3: 287–297. ISSN 1828-5384.

- Dallet, J.M. (1982). Dictionnaire Kabyle - Français (in French).

- Ferchiou, N. (1998-02-01). Cramps, Gabriel (ed.). "Fossa Regia". Encyclopédie Berbère (in French). Peeters Publishers. 19: 1–16.

- Fanciullo, Franco (1992). Kremer, Dieter (ed.). Un capitolo della Romania sommersa: il latino africano. Actes du XVIIIe Congrès internaitonal de linguistique et philologie romanes, I. Romania submersa - Romania nova (in Italian). 132. Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 162–187.

- Galdi, Giovanbattista (2011). Clackson, James (ed.). A Companion to the Latin Language. Blackwell Companions to the Ancient World. 132. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1444343373.

- Guédon, Stéphanie (2018). La frontière romaine de l'Africa sous le Haut-Empire. Bibliothèque de la Casa de Velázquez (in French). 74. Contributions by David Mattingly. Casa de Velázquez. ISBN 9788490962046.

- Haspelmath, Martin; Tadmor, Uri (2009). Loanwords in the World's Languages: A Comparative Handbook. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110218442.

- Kirschen, Bryan (2015). Judeo-Spanish and the Making of a Community. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. ISBN 9781443881586.

- Kossmann, Maarten (2013). The Arabic Influence on Northern Berber. Studies in Semitic Languages and Linguistics. Brill. ISBN 9789004253094.

- Kroll, Wilhelm (1897). "Das afrikanische Latein". Rheinisches Museum für Philologie (in German). 52: 569–590. JSTOR 41251699.

- Lausberg, Heinrich (1956). Göschen, Sammlung (ed.). Romanische Sprachwissenschaft (in German). Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- Lewicki, Tadeusz (1958). Une langue romaine oubliée de l'Afrique du Nord. Observations d'un arabisant. Rocznik Orientalistyczny (in French). (1951-1952) 17. pp. 415–480.

- Loporcaro, Michele (2011). Maiden, Martin; Smith, John Charles; Ledgeway, Adam (eds.). Phonological processes. The Cambridge History of the Romance Languages: Structures. 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521800723.

- Loporcaro, Michele (2015). Vowel Length from Latin to Romance. Oxford studies in diachronic and historical linguistics. 10. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199656554.

- Lorenzetti, Luca; Schirru, Giancarlo (2010). Tantillo, I. (ed.). Un indizio della conservazione di /k/ dinanzi a vocale anteriore nell'epigrafia cristiana di Tripolitania. Leptis magna. Una città e le sue iscrizioni in epoca tardoromana (in Italian). Cassino: Università di Cassino. pp. 303–311. ISBN 9788883170546.

- Martínez Díaz, Eva (2008). "An Approach to the Lingua Franca of the Mediterranean". Quaderns de la Mediterrània. 9: 223–227. S2CID 208221611.

- Mastino, Attilio (1990). L'Africa romana. Atti del 7. Convegno di studio 15-17 dicembre 1989 (in Italian). Sassari (Italia): Edizioni Gallizzi.

- Mastino, Attilio (2005). Storia della Sardegna Antica (PDF) (in Italian). Edizioni Il Maestrale. ISBN 8886109989.

- Matiacci, Silvia (2014). Lee, Benjamin Todd; Finkelpearl, Ellen; Graverini, Luca (eds.). Apuleius and Africitas. Apuleius and Africa: Routledge Monographs in Classical Studies. Routledge. ISBN 978-1136254093.

- Monceaux, Paul (2009). Ladjimi Sebaï, Leïla (ed.). Les Africains. Les intellectuels carthaginois (in French). 1. éditions cartaginoiseries. ISBN 978-9973704092.

- Paradisi, U. (1964). I tre giorni di Awussu a Zuara (Tripolitania). AION (in Italian). XIV. Naples: NS. pp. 415–419.

- Prevost, Virginie (2007-12-01). "Les dernières communautés chrétiennes autochtones d'Afrique du Nord". Revue de l'histoire des religions (in French). 4 (4): 461–483. doi:10.4000/rhr.5401. ISSN 0035-1423.

- Rubattu, Antoninu (2006). Dizionario universale della lingua di Sardegna: Italiano-sardo-italiano antico e moderno, M-Z (PDF). 2. EDES. ISBN 9788886002394.

- Rushworth, Alan (2004). Merrills, Andrew H. (ed.). From Arzuges to Rustamids: State Formation and Regional Identity in the Pre-Saharan Zone. Vandals, Romans and Berbers: New Perspectives on Late Antique North Africa. Ashgate. ISBN 9780754641452.

- Scales, Peter C. (1993). The Fall of the Caliphate of Córdoba: Berbers and Andalusis in Conflict. 9. Brill. ISBN 9789004098688.

- Schuchardt, Hugo (1918). Die romanischen Lehnwörter im Berberischen (in German). Wien.

- Varner, Eric R. (1990). "Two Portrait Stelae and the Romanization of North Africa". Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin. Yale University: 10–19. ISSN 0084-3539. JSTOR 40514450.

- Whittaker, Dick (2009). Derks, Ton; Roymans, Nico (eds.). Ethnic discourses on the frontiers of Roman Africa. Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity: The Role of Power and Tradition. Amsterdam University Press. pp. 189–206. ISBN 9789089640789. JSTOR j.ctt46n1n2.11.

- Wright, Roger (2012). "Late and Vulgar Latin in Muslim Spain: the African connection". Latin vulgaire – latin tardif IX. Actes du IXe colloque international sur le latin vulgaire et tardif, Lyon 2-6 septembre 2009 - Collection de la Maison de l'Orient méditerranéen ancien. Série philologique. Lyon: Maison de l'Orient et de la Méditerranée Jean Pouilloux. 49: 35–54.

Further reading

- Sayahi, Lotfi (2014). Diglossia and Language Contact: Language Variation and Change in North Africa. Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact Diglossia and Language Contact: Language Variation and Change in North Africa. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521119368.