Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic

The Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic (Latvian SSR; Latvian: Latvijas Padomju Sociālistiskā Republika; Russian: Латвийская Советская Социалистическая Республика, Latviyskaya Sovetskaya Sotsialisticheskaya Respublika), also known as Soviet Latvia or Latvia, was a republic of the Soviet Union.

Latvian Soviet Socialist Republic | |

|---|---|

| 1940–1990/91 1941–1944: German occupation | |

Location of Latvia (red) within the Soviet Union | |

| Status | Unrecognized Soviet Socialist Republic (1940–1941, 1944–1990/91) |

| Capital | Riga |

| Common languages | Russian Latvian |

| Government | Soviet Socialist Republic |

| First Secretary | |

• 1940–1959 | Jānis Kalnbērziņš (first) |

• 1990 | Alfrēds Rubiks (last) |

| Legislature | Supreme Soviet |

| Historical era | World War II · Cold War |

| 17 June 1940 | |

• SSR established | 21 July 1940 |

| 5 August 1940 | |

| 1941–1945 | |

• Soviet re-occupation SSR re-established | 1944/1945 |

| 4 May 1990 | |

• Independence recognized by the State Council of the Soviet Union | 6 September 1991 |

| Area | |

| 1989 | 64,589 km2 (24,938 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1989 | 2,666,567 |

| Currency | Soviet ruble (руб) (SUR) |

| Calling code | 7 013 |

| Today part of | |

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Latvia |

|

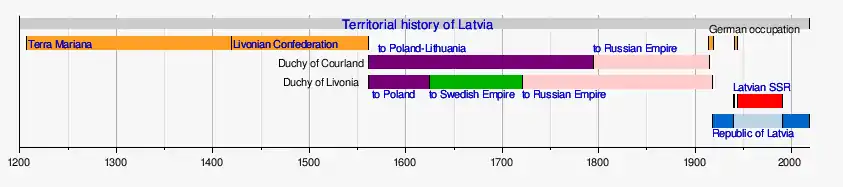

| Chronology |

|

|

It was established on 21 July 1940, during World War II, as a Soviet puppet state[1] in the territory of the previously independent Republic of Latvia after it had been occupied on June 17, 1940 by the Red Army, in conformity with the terms of the 23 August 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.

Following the Welles Declaration of July 23, 1940, the annexation of the Baltic states into the Soviet Union (USSR) on 5 August 1940 was not recognized as legitimate by the United States, the European Community, and recognition of it as the nominal thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth constituent republic of the USSR was withheld for five decades.[2] Its territory was subsequently conquered by Nazi Germany in June–July 1941, before being retaken by the Soviets in 1944–1945. Nevertheless, Latvia continued to exist as a de jure independent country with a number of countries continuing to recognize Latvian diplomats and consuls who still functioned in the name of their former governments.

Soviet rule came to an end during the dissolution of the Soviet Union. The first freely elected parliament of the Latvian SSR passed a declaration "On the Renewal of the Independence of the Republic of Latvia" on May 4, 1990, restoring the official name of the State of Latvia as the Republic of Latvia.[3] The full independence of the Republic of Latvia was restored on 21 August 1991, during the 1991 Soviet coup d'état attempt and fully recognized by the Soviet Union on 6 September 1991.

Creation, 1940

On September 24, 1939, the USSR entered the airspace of Estonia, flying numerous intelligence gathering operations. On September 25, Moscow demanded that Estonia sign a Soviet–Estonian Mutual Assistance Treaty that would allow the USSR to establish military bases and to station troops on its soil.[4] Latvia was next in line, as the USSR demanded the signing of a similar treaty. The authoritarian government of Kārlis Ulmanis accepted the ultimatum, signing the Soviet–Latvian Mutual Assistance Treaty on October 5, 1939. On June 16, 1940, after the USSR had already invaded Lithuania, it issued an ultimatum to Latvia which was followed by the Soviet occupation of Latvia on June 17.

Soviet foreign minister Vyacheslav Molotov accused Latvia and the other Baltic states of forming a military conspiracy against the Soviet Union, and so Moscow presented ultimatums, demanding new concessions, which included the replacement of governments with new ones, "determined" to "fulfill" the treaties of friendship "sincerely" and allowing an unlimited number of troops to enter the three countries.[5] Hundreds of thousands Soviet troops entered Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania.[6] These additional Soviet military forces far outnumbered the armies of each country.[7]

Ulmanis government decided that, in conditions of international isolation and the overwhelming Soviet force both on the borders and inside the country, it was better to avoid bloodshed and an unwinnable war.[8] The Latvian army did not fire a shot and was quickly decimated by purges and included in the Red Army.

Ulmanis' government resigned and was replaced by a left-wing government created under instructions from the USSR embassy. Up until the election of the People's Parliament on July 14–15, 1940 there were no public statements about governmental plans to introduce a Soviet political order or to join the Soviet Union. Soon after the occupation, the Communist Party of Latvia was legalized as the only legal party and presented the "Working People's Bloc" for the elections.[9] It was the only permitted participant in the election, after an attempt by other politicians to include the Democratic Bloc (an alliance of all banned Latvian parties, except the Social Democratic Workers' Party) on the ballot was prevented by the government. Its office was closed, election leaflets confiscated and its leaders arrested.[10]

The election results themselves were fabricated; the Soviet press service released them so early that they appeared in a London newspaper a full 24 hours before the polls had closed.[11][12][13] All Soviet army personnel present in the country were allowed to vote.[14]

The newly elected People's Parliament convened on 21 July to declare the creation of the Latvian SSR and request admission to the Soviet Union on the same day. Such a change in the basic constitutional order of the state was illegal under the Constitution of Latvia, because such a change could only be enacted after a plebiscite with two-thirds of the electorate approving. On August 5, the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union completed the process of annexation by accepting the Latvian petition, and formally incorporated Latvia into the Soviet Union.

Some of the Latvian diplomats stayed in the West and the Latvian Diplomatic Service continued to advocate the cause of Latvia's freedom for the next 50 years.

Following the Soviet pattern, the real power in the republic was in the hands of the First Secretary of the Communist Party of Latvia, while the titular head of the republic (Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet) and the head of the executive (the Chairman of the Soviet of the Ministers) were in subordinate positions. Therefore, the history of Soviet Latvia can broadly be divided in the periods of rule by the First Secretaries: Jānis Kalnbērziņš, Arvīds Pelše, Augusts Voss, Boris Pugo.

Era of Kalnbērziņš, 1940–1959

The Horrible Year, 1940–41

In the following months of 1940 the Soviet Constitution and criminal code (copied from Russian) were introduced. The elections of July 1940 were followed by elections to the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union in January 1941. The remaining Baltic Germans and anyone who could claim to be one emigrated to the German Reich.

On August 7, 1940 all print media and printing houses were nationalized. Most of the existing magazines and newspapers were discontinued or appeared under new, Soviet names. In November 1940 banning of books began, in total, some 4000 titles were banned and removed from circulation. Arrests and deportations of some authors, like Aleksandrs Grīns, began, while others, such as Jānis Sudrabkalns, started writing poems about Stalin.

As Latvia had implemented a sweeping land reform after the independence, most farms were too small for nationalization. While rumors of impending collectivization were officially denied in 1940 and 52,000 landless peasants were given small plots of up to 10 ha, in early 1941 preparations for collectivization began.[15] The small size of land plots and imposition of the production quotas and high taxes meant that very soon independent farmers would go bankrupt and had to establish collective farms.

Arrests and deportations to Soviet Union began even before Latvia officially become a part of it. Initially they were limited to the most prominent political and military leaders like President Kārlis Ulmanis, War minister Jānis Balodis and army chief Krišjānis Berķis who were arrested in July 1940. The Soviet NKVD also arrested most of the White Russian émigrés, who had found a refuge in Latvia. Very soon purges reached the upper echelons of the puppet government when minister of welfare Jūlijs Lācis was arrested.

June 14 deportations

In early 1941 the Soviet central government began planning the mass deportation of anti-Soviet elements from the occupied Baltic states. In preparation, General Ivan Serov, Deputy People's Commissar of Public Security of the Soviet Union, signed the Serov Instructions, "Regarding the Procedure for Carrying out the Deportation of Anti-Soviet Elements from Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia." During the night of 13–14 June 1941, 15,424 inhabitants of Latvia – including 1,771 Jews and 742 ethnic Russians – were deported to camps and special settlements, mostly in Siberia.[16] While among the deported were such obvious candidates as former politicians, wealthy businessmen and farmers, policemen, members of Aizsargi and NGO leaders, even philatelists and enthusiasts of Esperanto were included in the June deportation as unreliable elements. Some 600 Latvian officers were arrested in the Litene army camp, many of them executed on the spot. Many political prisoners were summarily executed in prisons all over Latvia during the hasty Soviet retreat after the German attack on June 22, 1941. In total Latvia lost some 35,000 people during the first year of the Soviet rule.

Some of the deportees had received warnings to stay away from home and were hiding either among friends or in forests. After the German-Soviet war began many of them organized small guerrilla units and attacked the retreating Red Army soldiers and greeted Germans with the flag of independent Latvia.

World War II, 1941–1945

The Nazi invasion, launched a week later, cut short immediate plans to deport several hundred thousand more from the Baltics. Nazi troops occupied Riga on 1 July 1941.

During the short period of interregnum Latvians created two bodies that sought to restore independent Latvia: the Central Organizing Committee for Liberated Latvia and the Provisional State Council.

Immediately after the installment of Nazi German authority, a process of eliminating the Jewish and Gypsy population began, with many killings taking place in Rumbula.

The killings were committed by the Einsatzgruppe A, the Wehrmacht and Marines (in Liepāja), as well as by Latvian collaborators, including the 500–1,500 members of the Arajs Commando (which alone killed around 26,000 Jews) and the 2,000 or more Latvian members of the SD.[17][18] By the end of 1941 almost the entire Jewish population was killed or placed in the death camps. In addition, some 25,000 Jews were brought from Germany, Austria and the present-day Czech Republic, of whom around 20,000 were killed. The Holocaust claimed approximately 85,000 lives in Latvia,[17] the vast majority of whom were Jews.

A large number of Latvians resisted the German occupation. The resistance movement was divided between the pro-independence politicians of the Latvian Central Council and the armed Soviet partisan units under the Latvian Partisan Movement Headquarters (латвийский штаб партизанского движения) in Moscow. Their Latvian commander was Arturs Sproģis.

The Nazis planned to Germanise the Baltics by settling some 520,000 German settlers there 20–25 years after the war.[15] In 1943 and 1944 two divisions of Latvian Legion were created through a forced mobilization and made a part of Waffen SS in order to help Germany against the Red Army.

Stalinism re-imposed, 1945–1953

In the middle of 1944, when the Soviet Operation Bagration reached Latvia, heavy fighting took place between German and Soviet troops which ended with a stalemate and creation of the Courland Pocket which allowed some 130,000 Latvians to escape to Sweden and Germany.

During the course of the war, both occupying forces conscripted Latvians into their armies, in this way increasing the loss of the nation's "live resources". In Courland, Latvian Legion units fought battles against Latvians of the Red Army.

In total, Latvia lost some 20% of its population during World War II. In 1944 part of Abrene District, about 2% of Latvia's territory, was illegally ceded to the RSFSR.

In 1944 the Soviets immediately began to reinstate the Soviet system. After re-establishing military control over the country, in February 1946, elections of the Soviet Union's Supreme Soviet were held, followed, in February 1947, by Latvian Supreme Soviet elections and only in January 1948 elections to the local Soviets.

Guerrilla movement

After the German surrender it became clear that Soviet forces were there to stay, and Latvian national partisans began their fight against another occupier: the Soviet Union. At their peak some 10,000–15,000 partisans in disorganized units fought local battles against Communists, NKVD troops and Soviet government representatives. Forest brothers consisted not only of the former Legionnaires or German supporters, but men who were trying to avoid Soviet conscription, dispossessed farmers, even priests and school pupils who wrote and distributed patriotic leaflets and provided shelter to partisans. Many believed that a new war between the Western powers and the Soviet Union was imminent and expected Latvia to be liberated soon. After the 1949 deportations and collectivization the resistance movement decreased sharply, with the last few individuals surrendering in 1956, when amnesty was offered. The last holdout was Jānis Pīnups, who hid from authorities until 1995.

Deportations of 1949

The first post-war years were marked by particularly dismal and sombre events in the fate of the Latvian nation. 120,000 Latvian inhabitants deemed disloyal by the Soviets were imprisoned or deported to Soviet concentration camps (the Gulag). Some managed to escape arrest and joined the Forest Brothers.

On 25 March 1949, 43,000 mostly rural residents ("kulaks") and Latvian patriots were deported to Siberia and northern Kazakhstan in a sweeping repressive Operation Priboi, which was implemented in all three Baltic States and approved in Moscow already on 29 January 1949. Whole families were arrested and almost 30% of deported were children under 16.

Collectivization

In the post-war period, Latvia was forced to adopt Soviet farming methods and the economic infrastructure developed in the 1920s and 1930s was eradicated. Farms belonging to refugees were confiscated, German supporters had their farm sizes sharply reduced and much of the farm land became state owned. The remaining farmers had their taxes and obligatory produce delivery quotas increased until individual farming became impossible. Many farmers killed their cattle and moved to cities. In 1948 collectivization began in earnest and was intensified after the March 1949 deportations and by the end of the year 93% of farms were collectivized.[19]

Collective farming was extremely unprofitable as farmers had to plant and harvest according to the state plan and not the actual harvest conditions. Farmers were paid close to nothing for their produce, as Stalinist system was based on squeezing them dry for the benefit of heavy industry and military needs. Grain production in Latvia collapsed from 1.37 million tons in 1940 to 0.73 million tons in 1950 and 0.43 million tons in 1956.[15] Only in 1965 did Latvia reach the meat and dairy output levels of 1940.

Russian dominance

During the first post-war years Moscow's control was enforced by the Special Bureau of CPSU Central Committee, led by Mikhail Suslov. To ensure total control over the local Communist party a Russian, Ivan Lebedev, was elected as the Second Secretary, this tradition continued until the end of the Soviet system. Lack of politically reliable local cadres meant that the Soviets increasingly placed Russians in party and government leadership positions. Many Russian Latvian Communists who had survived the so-called 1937–38 "Latvian Operation" during the Great Purge were sent back to the homeland of their parents. Most of these Soviets did not speak Latvian and this only enforced the wall of distrust against the local population. By 1953 Latvia's Communist Party had 42,000 members, half of whom were Latvians.[15]

To replace the lost population (due to war casualties, refugees to the West and deportees to the East) and to implement a heavy industrialization program, hundreds of thousands of Russians were moved to Latvia. An extensive program of Russification was initiated, limiting the use of Latvian and minority languages. In addition, the leading and progressive role of Russian people throughout the Latvian history was heavily emphasized in school books, arts and literature. The remaining poets, writers and painters had to follow the strict cannons of socialist realism and to live in constant fear of being accused of some ideological mistake which could lead to ban from publication or even arrest.

National communists, 1953–1959

During the short rule of Lavrentiy Beria in 1953, the policy of giving more power to local communists and respecting local languages was introduced. More freedoms came after the 1956 de-Stalinization. Some 30,000 survivors of Soviet deportations began returning to Latvia. Many of them were barred from working in certain professions or returning to their homes.

Soon after Stalin's death number of Latvians in Communist party began to increase. By this time many locally born communists had achieved positions of power and they began advocating a program that centered on ending the inflow of Russian speaking immigrants, end to the growth of heavy industry and creating light industries better suited for local needs, increasing the role and power of the locally born communists, enforcing the Latvian language as the state language.[20] This group was led by Eduards Berklavs who in 1957 became the Vice-Chairman of the Council of Ministers. Orders were issued that non-Latvian Communists should learn some Latvian within two years or lose their jobs.

They were opposed by the Russian Latvian communists who had been born to Latvian parents in Russia or Soviet Union, had returned to Latvia only after World War II and usually did not speak, or avoided speaking Latvian in public. They were supported by the politically influential officer corps of the Baltic Military District.

In 1958 Soviet education law made learning of national languages voluntary, in fact ending Russian interest in learning them.

In April 1959 a fact-finding delegation from Soviet Central Committee visited Riga. During Nikita Khrushchev's visit to Riga in June 1959 hard-line elements complained about the nationalist tendencies in the Party and with the blessing from the Moscow started purges of national communists and local communists, who had been in power since 1940. In November 1959 the long-serving First Secretary of the Party Kalnbērziņš and Prime Minister Vilis Lācis resigned from their posts and were replaced by hardliners. During the next three years some 2000 national communists were dismissed from their positions, moved to insignificant posts in countryside or Russia.

The first post-war census in 1959 showed that the number of Latvians since 1935 had declined by 170,000, while Russians had increased by 388,000, Belorussians by 35,000 and Ukrainians by 28,000.[21]

Because Latvia had still maintained a well-developed infrastructure and educated specialists it was decided in Moscow that some of the Soviet Union's most advanced manufacturing factories were to be based in Latvia. New industry was created in Latvia, including a major machinery factory RAF and electrotechnical factories, as well as some food and oil processing plants. TV broadcasts from Riga started in 1954, the first in the Baltics.

Era of Pelše, 1959–1966

During 1959–1962 the leading Latvian national communists were purged as Arvīds Pelše enforced his power. For almost 30 years Communist Party and government was led by the conservative Russian Latvians.

The orthodox marxist Pelše is often remembered for the official ban in 1961 of the Latvian midsummer Jāņi celebrations and many other Latvian traditions and folk customs. He established the pattern of total obedience to Moscow and increased Russification of Latvia, especially Riga.

Between 1959 and 1968 nearly 130,000 Russian speakers immigrated to Latvia and began working in the large industrial factories that were built at rapid speed. The newly arrived immigrants were the first in line to receive apartments in the newly built micro-districts. Very soon the Soviet Latvia's industrial model was created. Large factories, employing tens of thousands of recently arrived immigrants, and completely dependent on resources from faraway Soviet regions, produced products – the majority of which were then sent back to other Soviet republics. Many of the new factories were under All-Union ministry and military jurisdiction, thus operating outside the planned economy of the Soviet Latvia. Latvia's VEF and Radiotehnika factories specialized in production of radios, telephones and sound systems. Most of the Soviet railway carriages were made in Rīgas Vagonbūves Rūpnīca and mini buses in Riga Autobus Factory.

In 1962 Riga began receiving Russian gas for industrial needs and domestic heating. This allowed large scale construction of new micro-districts and high-rises to begin. In 1965 Pļaviņas Hydroelectric Power Station began producing electricity.

Era of Voss, 1966–1984

Soviet stamp in honor of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, 1967

Soviet stamp in honor of the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, 1967 Soviet stamp celebrating 40 years of the Latvian SSR

Soviet stamp celebrating 40 years of the Latvian SSR Train built in RVR

Train built in RVR The iconic RAF minibus

The iconic RAF minibus Monument to the Red Latvian Riflemen in Riga

Monument to the Red Latvian Riflemen in Riga.jpg.webp) The abandoned House of Press

The abandoned House of Press Soviet nomenklatura sanatorium in Jūrmala

Soviet nomenklatura sanatorium in Jūrmala

The high point of the Soviet rule was reached during the Brezhnev stagnation. As there were not enough people to operate the newly built factories and order to expand industrial production, workers from outside of Latvian SSR (mainly Russians) were transferred into the country, noticeably decreasing the proportion of ethnic Latvians. The speed of Russification was also influenced by the fact that Riga was the HQ of the Baltic Military District with many thousands of active and retired Soviet officers moving there.

Increased investments and subsidies for collective farms greatly increased the living standards of rural population without much increase in production output. Much of the farm produce was still grown in the small private plots. In order to improve rural living standards, a mass campaign was started to liquidate individual family farms and to move people into smaller agricultural towns where they were given apartments. From farmers they became paid workers in collective farms.[22]

While the early Voss era continued with the modernizing impulse of the 1960s, a visible stagnation began by the mid-1970s. High-rise prestige objects in Riga, such as hotel Latvija and Ministry of Agriculture took many years to complete. A new international airport and Vanšu Bridge over Daugava were built.

An ideological model of "live and let live" set in. Public demonstrations of enthusiastic support for the Soviet regime were required on revolutionary anniversaries, while black market, absenteeism and alcoholism became widespread. Food and consumer goods shortages were a norm. Latvians turned to escapism: the music of Raimonds Pauls, historic comedies of Riga Film Studio and even Poetry Days became hugely popular.

Era of Pugo, 1984–1988

National reawakening, 1985–1990

In the second half of the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev started to introduce political and economic reforms called glasnost and Perestroika. In the summer of 1987 large demonstrations were held in Riga at the Freedom Monument, a symbol of national independence. In the summer of 1988 a national movement cohered in the Popular Front of Latvia. The Latvian SSR, along with the other Baltic Republics, was allowed greater autonomy and in 1988 the old national flag of Latvia was legalized, replacing the Soviet Latvian flag as the official flag in 1990. Pro-independence Latvian Popular Front candidates gained a two-thirds majority in the Supreme Council in the March 1990 democratic elections.

Collapse, 1990–1991

.svg.png.webp)

On May 4, 1990; the Council passed the declaration "On the Restoration of Independence of the Republic of Latvia," which declared the Soviet annexation void and announced the start of a transitional period to independence. It argued that the 1940 occupation violated international law. It also argued that the 1940 resolution acceding to the Soviet Union was illegal, since the 1922 Latvian constitution stipulated that any major change in the state order had to be submitted to a referendum. In any case, the declaration argued that the 1940 elections were conducted on the basis of an illegal and unconstitutional election law, which rendered all actions of the "People's Saeima" ipso facto void. On these bases, the Supreme Council argued that the Republic of Latvia, as proclaimed in 1918, still legally existed even though its sovereignty had been de facto lost in 1940.[23]

Latvia took the position that it did not need to follow the process of secession delineated in the Soviet constitution, arguing that since the annexation was illegal and unconstitutional, it was merely reasserting an independence that still existed under international law. However, the central power in Moscow continued to regard Latvia as a Soviet republic in 1990–1991. In January 1991, Soviet political and military forces tried unsuccessfully to overthrow the Republic of Latvia authorities by occupying the central publishing house in Riga and establishing a Committee of National Salvation to usurp governmental functions. During the transitional period Moscow maintained many central Soviet state authorities in Latvia. In spite of this, seventy-three percent of all Latvian residents confirmed their strong support for independence on March 3, 1991, in a non-binding advisory referendum. A large number of ethnic Russians also voted for the proposition. The Republic of Latvia declared the end of the transitional period and restored full independence on 21 August 1991 in the aftermath of the failed Soviet coup attempt.[24] Latvia, as well as Lithuania and Estonia de facto ceased to be parts of the USSR four months before the Soviet Union itself ceased to exist (26 December 1991). Soon, on 6 September, the independence of three Baltic states was recognized by the USSR. Today's Republic of Latvia and other Baltic states consider themselves to be the legal continuation of the sovereign states whose first independent existence dates back to 1918–1940, and does not accept any legal connection with the former Latvian SSR which had been occupied and annexed into USSR 1940–1941 and 1944–1991. Since independence, the Communist Party of the Latvian SSR was discontinued, and a number of high-ranking Latvian SSR officials faced prosecution for their role in various human rights abuses during the Latvian SSR regime. Latvia later joined NATO and the European Union in 2004.

Economy

The Soviet period saw rebuilding and increase of the industrial capacity, including the automobile (RAF) and electrotechnic (VEF) factories, food-processing industry, oil pipelines and the bulk-oil port Ventspils.

Part of the incorporation of the Latvian SSR into the Soviet Union was the introduction of the Russian language into all spheres of public life. Russian became a prerequisite for admission to higher education and better job occupations. It was also made a compulsory subject in all Latvian schools. Vast numbers of people were needed for the new factories and they were purposefully sent there from different parts of Russia, thus creating a situation wherein bigger towns became more and more russified up until the 1980s.

National income per capita was higher in Latvia than elsewhere in the USSR (42% above the Soviet average in 1968);[25] however Latvia was at the same time a relative contributor to the Federation's centre with an estimated 0.5% of the Latvian GDP going to Moscow.[26] After the collapse of the Soviet Union, all of the economy branches associated with it collapsed as well. While a significant Russian presence in Latgale predated the Soviet Union (~30%), the intense industrialization and the heavy importation of labor from the Soviet Union to support it, led to significant increases in the Russian minority in Riga, even forming a majority in Latvian urban centers such as Daugavpils, Rēzekne, Ogre. Those areas were also hardest hit economically when the Soviet Union collapsed, leading to massive unemployment. Sharp disagreement with Russia over the legacy of the Soviet era has led to punitive economic measures by Russia, including the demise of transit trade as Russia cut off petroleum exports through Ventspils in 2003 (eliminating 99% of its shipments) after the government of Latvia refused to sell the oil port to the Russian state oil company, Transneft.[27] The result is that only a fraction of Latvia's economy is connected with Russia, especially after it joined the European Union.

In 2016, a committee of historians and economists published a report "Latvian Industry Before and After Restoration of Independence" estimating overall cost of Soviet occupation in the years 1940–1990 at 185 billion euros, not counting the untangible costs of "deportations and imprisonment policy" of the Soviet authorities.[28]

Soviet army presence

The Soviet army had been stationed in Latvia since October 1939, when it demanded and received military bases in Courland where it stationed at least 25,000 soldiers, with air force, tanks and artillery support. The Soviet navy received rights to use ports in Ventspils and Liepāja. In addition to soldiers, uncontrolled numbers of officers' family members and construction workers arrived.

During the first year of Soviet power, construction of the new military aerodromes was begun, often involving local population as unpaid construction workers. The Soviet navy took over seaports and shipping yards. Many hundreds of Soviet officers were moved into newly nationalized apartments and houses. Larger apartments were subdivided, creating communal apartments.

After 1944, Latvia and Riga became heavily militarized. Demobilized soldiers and officers chose to move to Riga, creating severe housing shortages. Much of the new apartment building in the first post-war years was done only for the benefit of Soviet officers stationed in Riga.

The whole Baltic Sea coast of Courland became a Soviet border area with limited freedom of movement for the local inhabitants and closed for outsiders. Beaches were illuminated by searchlights and plowed, to show any footprints. The old fishing villages became closed military zones, fishermen were moved to larger towns: Roja, Kolka. The small coastal nation of Livonians virtually ceased to exist. Secret objects, like the Irbene radio telescope were built here. Liepāja port was littered with rusting submarines and beaches with unexploded phosphorus.

By the mid-1980s, in addition to 350,000 soldiers of the Baltic Military District, an unknown number of border and interior ministry troops were stationed in the Baltics. In 1994 the departing Russian troops presented a list of over 3000 military units that were stationed in 700 sites taking over 120,000 ha, or about 10% of Latvian land.[29]

In addition to active military personnel, Riga was popular as a retirement town for Soviet officers, who could not retire to larger cities like Moscow or Kiev. Many thousands of them received preferential treatment in receiving new housing. In order to speed up the withdrawal of Russian army, Latvia officially agreed to allow 20,000 retired Soviet officers and their families (up to 50,000 people) to remain in Latvia without granting them citizenship and Russia continues to pay them pensions.[30]

Military training was provided by the Riga Higher Military Political School and the Riga Higher Military Aviation Engineering School.

International status

The governments of the Baltic countries,[31][32] the European Court of Human Rights,[33] the United Nations Human Rights Council,[34] the United States,[35] and the European Union (EU),[36][37] regard Latvia as being occupied by the Soviet Union in 1940 under the provisions of the 1939 Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The European Parliament in recognising[38] the occupation of the Baltic states from 1940 until the fall of the Soviet Union as illegal, led to the early acceptance of the Baltic states into the NATO alliance.

Soviet sources prior to Perestroika

Up to the reassessment of Soviet history in USSR that began during Perestroika, before the USSR had condemned the 1939 secret protocol between Nazi Germany and itself that had led to the invasion and occupation of the three Baltic countries,[39] the events in 1939 were as follows: The Government of the Soviet Union suggested that the Governments of the Baltic countries conclude mutual assistance treaties between the countries. Pressure from working people forced the governments of the Baltic countries to accept this suggestion. The Pacts of Mutual Assistance were then signed[40] which allowed the USSR to station a limited number of Red Army units in the Baltic countries. Economic difficulties and dissatisfaction of the populace with the Baltic governments' policies that had sabotaged fulfillment of the Pact and the Baltic countries governments' political orientation towards Nazi Germany led to a revolutionary situation in June, 1940. To guarantee fulfillment of the Pact, additional military units entered Baltic countries, welcomed by the workers who demanded the resignations of the Baltic governments. In June under the leadership of the Communist Parties political demonstrations by workers were held. The fascist governments were overthrown, and workers' governments formed. In July 1940, elections for the Baltic Parliaments were held. The "Working People's Unions", created by an initiative of the Communist Parties, received the majority of the votes.[41] The Parliaments adopted the declarations of the restoration of Soviet powers in Baltic countries and proclaimed the Soviet Socialist Republics. Declarations of Estonia's, Latvia's and Lithuania's wishes to join the USSR were adopted and the Supreme Soviet of the USSR petitioned accordingly. The requests were approved by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR.

Current position of the Russian government

The Russian government and officials maintain that the Soviet annexation of the Baltic states was legitimate[42] and that the Soviet Union liberated the countries from the Nazis.[43][44] They state that the Soviet Union acted in response to Germany-oriented policies of the three Baltic states that resulted from alleged secret talks conducted by the governments of these states with Nazi leadership[45] and that the subsequent entry of additional Soviet troops into the Baltics in 1940 was done following the agreements and with the consent of the then governments of the Baltic republics. Thus the official postulates of the Soviet historiography are continued without significant amendments. They also maintain that the USSR was not in a state of war and was not waging any combat activities on the territory of the three Baltic states; therefore, the word 'occupation' cannot be used. The Russian Foreign Ministry stated that "The assertions about [the] 'occupation' by the Soviet Union and the related claims ignore all legal, historical and political realities, and are therefore utterly groundless."[46]

Timeline

|

References

- Ronen, Yaël (2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes Under International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-19777-9.

- "Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of the Welles Declaration". Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- Declaration of the Supreme Soviet of the Latvian SSR on May 4, 1990 Archived April 8, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania by David J. Smith, Page 24, ISBN 0-415-28580-1

- see report of Latvian Chargé d'affaires, Fricis Kociņš, regarding the talks with Soviet Foreign Commissar Molotov in I.Grava-Kreituse, I.Feldmanis, J.Goldmanis, A.Stranga. (1995). Latvijas okupācija un aneksija 1939–1940: Dokumenti un materiāli. (The Occupation and Annexation of Latvia: 1939–1940. Documents and Materials.) (in Latvian). pp. 348–350. Archived from the original on 2008-11-06.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- nearly 650,000 according to Kenneth Christie; Robert Cribb (2002). Historical Injustice and Democratic Transition in Eastern Asia and Northern Europe: Ghosts at the Table of Democracy. RoutledgeCurzon. p. 83. ISBN 0-7007-1599-1.

- Stephane Courtois; Werth, Nicolas; Panne, Jean-Louis; Paczkowski, Andrzej; Bartosek, Karel; Margolin, Jean-Louis & Kramer, Mark (1999). The Black Book of Communism: Crimes, Terror, Repression. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-07608-7.

- The Baltic States: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania p.19 ISBN 0-415-28580-1

- Vincent E McHale (1983) Political parties of Europe, Greenwood Press, p450 ISBN 0-313-23804-9

- Misiunas & Taagepera, p26

- Mangulis, Visvaldis (1983). "VIII. September 1939 to June 1941". Latvia in the Wars of the 20th century. Princeton Junction: Cognition Books. ISBN 0-912881-00-3.

- Švābe, Arvīds. The Story of Latvia. Latvian National Foundation. Stockholm. 1949.

- Ferdinand Feldbrugge (1985). Encyclopedia of Soviet Law. Brill. p. 460. ISBN 90-247-3075-9.

- Attitudes of the Major Soviet Nationalities, Center for International Studies, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1973

- The Baltic States, Years of Dependence, 1940-1980

- Elmārs Pelkaus, ed. (2001). Aizvestie: 1941. gada 14. jūnijā (in Latvian, English, and Russian). Riga: Latvijas Valsts arhīvs; Nordik. ISBN 9984-675-55-6. OCLC 52264782.

- Ezergailis, A. The Holocaust in Latvia, 1996

- "Simon Wiesenthal Center Multimedia Learning Center Online". Archived from the original on 2007-01-10. Retrieved 2009-04-30.

- Valdis O. Lumans, Latvia in World War II, Fordham Univ Press, 2006, ISBN 978-08-23-22627-6, p. 398.

- The Rise and Fall of the Latvian National Communists

- Latvia: The Challenges of Change

- Latvija, 1969-1978

- Par Latvijas Republikas neatkarības atjaunošanu

- "History - Embassy of Finland, Riga". Embassy of Finland, Riga. 2008-07-09. Retrieved 2010-09-02.

Latvia declared independence on 21 August 1991...The decision to restore diplomatic relations took effect on 29 August 1991

- Misiunas, Romuald J.; Rein Taagepera (1993). The Baltic States, years of dependence, 1940–1990. University of California Press. pp. 185. ISBN 978-0-520-08228-1.

- Izvestija, "Опубликованы расчеты СССР с прибалтийскими республиками" 9 октября 2012, 14:56

- Latvia turns to EU for help in resolving oil impasse, AP WorldStream Tuesday, February 4, 2003.

- "Soviet occupation cost Latvian economy €185 billion, says research". Public Broadcasting of Latvia. April 18, 2016. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Latvija – Padomju Savienības karabāze

- Russian-Latvian treaty

- Feldmanis, Inesis (December 15, 2015). "The Occupation of Latvia: Aspects of History and International Law". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Latvia. Retrieved April 22, 2016.

- Estonia says Soviet occupation justifies it staying away from Moscow celebrations - Pravda.Ru Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine

- European Court of Human Rights cases on Occupation of Baltic States

- UNITED NATIONS Human Rights Council Report

- U.S.-Baltic Relations: Celebrating 85 Years of Friendship at state.gov

- European Parliament (January 13, 1983). "Resolution on the situation in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". Official Journal of the European Communities. C 42/78.

- Motion for a resolution on the Situation in Estonia by the EU

- European Parliament (January 13, 1983). "Resolution on the situation in Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania". Official Journal of the European Communities. C 42/78.

...calling on the United Nations to recognize the rights of the Baltic States to self-determination and independence...

- The Forty-Third Session of the UN Sub-Commission Archived 2015-10-19 at the Wayback Machine at Google Scholar

- (in Russian)1939 USSR-Latvia Mutual Aid Pact (full text)

- Great Soviet Encyclopedia

- Russia and the Baltic States: Not a Case of "Flawed" History - interview with Mikhail Demurin, head of the Executive Committee International Department of the Rodina (Homeland) party.

- BBC News: Europe (5 May 2005). "Russia denies Baltic 'occupation'". Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- BBC News: Europe (7 May 2005). "Bush denounces Soviet domination". Retrieved 10 August 2008.

- "Russian intelligence justifies Soviet annexation of Baltic states" - from RIA Novosti, 23.11.2006

- "Russia's rejection of Lithuania occupation claims final -ministry" - from newsfromrussia.ru, 18.01.2007

External links

- "Ethnic structure of Latvia" at lettia.lv, illustrating changes in population of Latvia over the last hundred years.

.svg.png.webp)

.svg.png.webp)