Fall of the inner German border

The inner German border rapidly and unexpectedly fell in November 1989, along with the fall of the Berlin Wall. The event paved the way for the ultimate reunification of Germany just short of a year later.

.jpg.webp)

Refugee crisis of September–November 1989

Hundreds of thousands of East Germans found an escape route across the border of East Germany's erstwhile ally, Hungary. The inner German border's integrity relied ultimately on other Warsaw Pact states fortifying their own borders and being willing to shoot escapees, including East Germans, around fifty of whom were shot on the borders of Polish People's Republic, Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, Hungarian People's Republic, Socialist Republic of Romania and People's Republic of Bulgaria between 1947 and 1989.[1] However, this meant that as soon as one of the other eastern bloc nations relaxed its border controls, the East Germans would be able to exit in large numbers.

Such a scenario played out in 1989 when Hungary dismantled its border fence with Austria. Hungary was at that time a popular tourist destination for East Germans, due to the trappings of prosperity that were absent at home – good and plentiful food and wine, pleasant camping and a lively capital city.[2] At home, the desire for reform was being driven by East Germany's worsening economic stagnation and the example of other eastern bloc nations who were following Gorbachev's example in instituting glasnost (openness) and perestroika (reform). However, the hardline East German leader, Erich Honecker – who had been responsible for the building of the Berlin Wall in 1961 – remained staunchly against any reform in his country. Declaring that "Socialism and capitalism are like fire and water", he predicted in January 1989 that "the Wall will stand for another hundred years."[3]

Hungary was the earliest of any eastern bloc nation to institute reform under its reformist Prime Minister Miklós Németh, who took office in November 1988.[4] Its government was still notionally Communist but planned free elections and economic reform as part of a strategy of "rejoining Europe" and reforming its struggling economy.[5] Opening the border was essential to this effort; West Germany had secretly offered a much-needed hard currency loan of DM 500 million ($250 million) in return for allowing citizens of the GDR to freely emigrate.[6] The Hungarians went ahead in May 1989 by dismantling the Iron Curtain along their border with Austria. To the consternation of the East German government, pictures of the barbed-wire fences being taken down were transmitted into East Germany by West German television stations.[7] A mass exodus by hundreds of thousands of East Germans began in September 1989. Thousands more scaled the walls of the West German embassies in Prague, Warsaw and Budapest claiming asylum. The West German mission in East Berlin was forced to close because it could not cope with the numbers of East Germans seeking asylum.[8] The hardline Czechoslovak Communist leader, Milouš Jakeš, agreed to Erich Honecker's request to choke off the flow of refugees by closing Czechoslovakia's border with East Germany, thus preventing East Germans from reaching Hungary.[9]

This, however, proved to be the start of a series of disastrous miscalculations by Honecker. There were rowdy scenes across East Germany as furious East Germans who had paid in advance for their plane or train tickets and accommodation found that they could not travel and that their hard-earned money had been lost.[10] The 14,000 East German refugees camping in the grounds of the West German embassy in Prague had to be dealt with; Honecker sought to humiliate them publicly by expelling them through East Germany to the West, shipping them in eight sealed trains from Prague and stripping them of their East German citizenship while branding them as "traitors". The Party justified the evacuation of the refugees as a humanitarian action taken because children were involved, who had been "let down by the irresponsible actions of their parents."[10] The state newspaper Neues Deutschland ran an editorial, said to have been dictated by Honecker personally, which declared that "by their behaviour they have trampled on all moral values and excluded themselves from our society." Far from discrediting the refugees, the trains produced uproar, with citizens waving and cheering the refugees as they passed through the East German countryside. Torn-up identity papers and East German passports littered the tracks as the refugees threw them out of the windows. When the trains arrived in Dresden, 1,500 East Germans stormed the main railway station in an attempt to board the trains. Dozens were injured and the station concourse was virtually destroyed.[11]

Honecker's more fundamental miscalculation was the presumption that by closing East Germany's last open border he had finally imprisoned his country's citizens within their own borders and made it clear that there would be no reform whatsoever – a situation that most East Germans found intolerable. Small pro-democracy demonstrations rapidly swelled into crowds of hundreds of thousands of people in cities across East Germany. The demonstrators chanted slogans such as Wir bleiben hier! ("We're staying here!") – indicating their desire to stay and fight for democracy – and "Wir sind das Volk" ("We are the people"), challenging the SED's claim to speak for the people. Some in the East German leadership advocated a crackdown, particularly the veteran secret police chief Erich Mielke. Although preparations for a Tiananmen Square-style military intervention were well advanced, ultimately the leadership ducked the decision to use force. East Germany was, in any case, in a very different situation from China; it depended on loans from the West and the continued support of the Soviets, both of which would have been critically jeopardised by a massacre of unarmed demonstrators. The Soviet army units in East Germany had reportedly been ordered not to intervene, and the lack of support from the Soviet leadership weighed heavily on the SED leadership as it tried to decide what to do.[12]

After Honecker was publicly chided by Gorbachev in October 1989 for his refusal to embrace reform, reformist members of the East German Politbüro sought to rescue the situation by forcing the resignation of the veteran Party chairman. He was replaced by the marginally less hardline Egon Krenz, who was seen as Honecker's protégé.[13] The new government sought to appease the protesters by reopening the border with Czechoslovakia. This, however, merely resulted in the resumption of the mass exodus through Hungary. The refugee flow had severely disruptive effects on the economy. Schools were closed because the teachers had fled; factories and offices shut down because of lack of essential staff; even milk rounds were cancelled after the milkmen departed. The chaos produced a revolt within the ranks of the SED against the corruption and incompetence of the party leadership. The formerly subservient GDR media began publishing eye-opening reports of high-level corruption, spurring demands for fundamental reform. On 8 November 1989, with mass demonstrations continuing across the country, the entire Politbüro resigned and a new, more moderate Politburo was appointed under Krenz's continued leadership.[14]

Opening of the border and the fall of the GDR

The East German government eventually sought to defuse the situation by relaxing the country's border controls. The intention was to allow emigration to West Germany but only after an application had been approved, and similarly to allow thirty-day visas for travel to the West, again on application. Only four million GDR citizens had a passport, so only that number could take immediate advantage of such a change; the remaining 13 million would have to apply for a passport and then wait at least four weeks for approval. The new regime would go into effect from 10 November 1989.[15]

The decision was reportedly made with little discussion by the Politbüro or understanding of the consequences. It was announced on the evening of 9 November 1989 by Politburo member Günter Schabowski at a somewhat chaotic press conference in East Berlin. The new border control regime was proclaimed as a means of liberating the people from a situation of psychological pressure by legalising and simplifying migration. Schabowski had been handed out a note with hand-written annotations but without the crucial information, the date where these rules would come into effect, on it. These had been passed only verbally between the Politbüro members on their latest meetings, which Schabowski hadn't attended. In answer to a press question about when the new travelling rules come into effect, Schabowski read that note. On the repeated press question about the date when these rules would come into effect, he rechecked the document and finding no date he answered slightly irritated, "As far as I know, ..., it's ... immediately, without delay", rather than from the following day, as intended. Crucially, in the light of what happened next, it was not meant to be an uncontrolled opening, nor was it meant to apply to East Germans wishing to visit the West as tourists.[15] At an interview in English after the press conference, Schabowski told the NBC reporter Tom Brokaw that "it is no question of tourism. It is a permission of leaving the GDR [permanently]."[16]

Within hours, thousands of people gathered at the Berlin Wall demanding that the border guards open the gates. The guards were unable to contact their superiors for instructions and, fearing a stampede, opened the gates. The iconic scenes that followed – people pouring into West Berlin, standing on the Wall and attacking it with pickaxes – were broadcast worldwide.[17]

While the eyes of the world were on Berlin, watching the Mauerfall (fall of the Wall), a simultaneous process of Grenzöffnung (border opening) was taking place along the entire length of the inner German border. Existing border crossings were opened immediately, though their limited capacity caused long tailbacks as millions of East Germans crossed over to the West. Within the first four days, 4.3 million East Germans – a quarter of the country's entire population – poured into West Germany.[18] At the Helmstedt crossing point on the Hanover–Berlin autobahn, cars were backed up for 65 km (40 mi); some drivers waited 11 hours to drive across to the West.[19] The border was opened progressively over the course of the next few months. New crossing points were created at many points, reconnecting communities that had been separated for nearly 40 years. At Herrenhof on the Elbe, hundreds of East Germans pushed their way through the border fence to board the first cross-river ferry to run since April 1945.[20] Hundreds of people from the East German town of Katherinenberg surged across the border to see the West German border town of Wanfried, while West Germans poured into East Germany "to see how you live on the other side". East German border guards, overwhelmed by the flood of people, soon gave up checking passports.[21] Special trains were put on to transport people across the border. The BBC correspondent Ben Bradshaw described the jubilant scenes at the railway station of Hof in Bavaria in the early hours of 12 November:

It was not just the arrivals at Hof who wore their emotions on their sleeves. The local people turned out in their hundreds to welcome them; stout men and women in their Sunday best, twice or three times the average age of those getting off the trains, wept as they clapped. 'These are our people, free at last,' they said ... Those arriving at Hof report people lining the route of the trains in East Germany waving and clapping and holding placards saying: 'We're coming soon.'[22]

Even the East German border guards were not immune to the euphoria. Peter Zahn, a border guard at the time, described how he and his colleagues reacted to the opening of the border:

After the Wall fell, we were in a state of delirium. We submitted a request for our reserve activities to be ended, which was approved a few days later. We visited Helmstedt and Braunschweig in West Germany, which would have been impossible before. In the NVA even listening to Western radio stations was punishable and there we were on an outing in the West.[23]

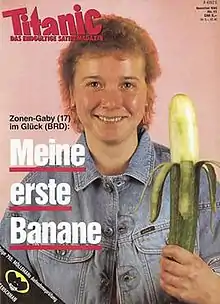

To the surprise of many West Germans, many East Germans spent their DM 100 "welcome money" buying great quantities of bananas, a highly prized rarity in the East. For months after the opening of the border, bananas were sold out at supermarkets along the border as East Germans bought whole crates because they did not believe that they would be on sale the next day.[24] The easterners' obsession with bananas was famously spoofed by the West German satirical magazine Titanic, which published a front cover depicting "[East-]Zone Gaby (17), in Bliss (West Germany): My first banana". Gaby is shown holding a large peeled cucumber.[25]

The opening of the border had a profound political and psychological effect on the East German public. The official mythology of the GDR had held that (in the words of the SED's official anthem) "the Party, the Party, the Party is always right / And comrades, it will stay that way. / For who fights for what's right is always right / Against lies and exploitation."[26] Those crossing the border, however, found that West Germany had achieved vastly superior prosperity without socialism, brotherhood with the Soviet Union, revolutionary values and the rest of the self-justifying mythology that underlay the SED's claims to moral superiority. The power of the SED's mythology evaporated overnight and previously prized ideological attributes became liabilities, rather than stepping stones for advancement.[27]

For many people the very existence of the GDR, which the SED had justified as the first "Socialist state on German soil", came to seem pointless. The state was bankrupt, the economy collapsing, the political class discredited, the governing institutions in chaos and the people demoralised by the evaporation of the collective assumptions which had underpinned their society for nearly fifty years. As Alan L. Nothnagle puts it, "Once its crutches were kicked away, GDR society had nothing to hold on to, least of all its national values. Not since Cortés and his conquistadors entered Mexico City has a society imploded so thoroughly."[28] The SED had hoped to regain control of the situation by opening the border but found that it had completely lost control. Membership of the Party collapsed and Krenz himself resigned on 6 December 1989 after only 50 days in office, handing over to the moderate Hans Modrow.[29] The removal of restrictions on travel prompted hundreds of thousands of East Germans to migrate to the West – over 116,000 of them between 9 November and 31 December 1989, compared with 40,000 for the whole of the previous year.[30]

The new East German leadership initiated "round table" talks with opposition groups, similar to the processes that had led to multi-party elections in Hungary and Poland.[31] When the first free elections were held in March 1990, the former SED, which had renamed itself PDS, was swept out of power and replaced by a pro-reunification Alliance for Germany coalition led by the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), Chancellor Kohl's party. Now that the CDU was in power on both sides of the border, the two countries progressed rapidly towards reunification, while international diplomacy paved the way abroad. In July 1990, monetary reunification was achieved and the Western Deutsche Mark replaced the East German mark as the East German currency[32] at a 1:1 ratio (1:2 for larger amounts). The biggest remaining obstacle, the question of NATO-membership of a unified Germany, was removed in a private visit of the German leaders to Gorbachev's dacha in the Caucasus mountains.[33] A Treaty on the Establishment of a Unified Germany was agreed in August 1990 and Germany's political reunification took place on 3 October 1990.[34]

Abandonment of the border

Following the opening of the border, it was progressively run down and eventually abandoned. Dozens of new crossings had been opened along the border by February 1990, and the border guards no longer carried weapons or made much effort to check travellers' passports.[35] The border guards' numbers were rapidly reduced. Half were dismissed within five months of the opening of the border.[36] The border was abandoned and the Grenztruppen were officially abolished on 1 July 1990;[34] all but 2,000 of them were dismissed or transferred to other jobs. The Bundeswehr gave the remaining border guards and other ex-NVA soldiers the task of clearing the border fortifications, which was only completed in 1994. The scale of the task was immense, as not only did the fortifications have to be cleared but hundreds of roads and railway lines had to be rebuilt.[37] An additional complication was caused by the presence of mines along the border. Although the 1.4 million mines laid by the GDR were supposed to have been removed in the 1980s, it was found that 34,000 were unaccounted for.[38] A further 1,100 mines were found and removed following Germany's reunification, at a cost of over DM 250 million,[39] in a programme that was not concluded until the end of 1995.[40]

The border clearers' task was aided unofficially by German civilians from both sides of the former border who scavenged the installations for fencing, wire and blocks of concrete to use in home improvements. As one East German commented in April 1990, "Last year, they used this fence to keep us in. This year, I'll use it to keep my chickens." Much of the fence was sold to a West German scrap-metal company at the rate of about $4 per segment. Environmental groups undertook a programme of re-greening the border, planting new trees and sowing grass seeds to fill in the clear-cut area along the border line.[36]

See also

Notes

- Todesopfer der DDR. Gedenkstätte Deutsche Teilung Marienborn

- Meyer (2009), p. 68

- Meyer (2009), pp. 26, 66

- Meyer (2009), p. 32

- Meyer (2009), p. 114

- Meyer (2009), p. 105

- Meyer (2009), p. 90

- Childs (2001), p. 67

- Meyer (2009), p. 122

- Childs (2001), p. 68

- Sebasteyen (2009), pp. 329–331

- Childs (2001), p. 75

- Childs (2001), pp. 82–83

- Childs (2001), p. 85

- Hertle (2007), p. 147

- Childs (2001), p. 87

- Childs (2001), p. 88

- Childs (2001), p. 89

- Jacoby, Jeff (8 November 1989). "The Wall came tumbling down". Boston Globe.

- Eliason, Michael (28 January 1990). "A journey along the Iron Curtain today". The Associated Press.

- "Sister cities swap citizens across border for a day". The Associated Press. 13 November 1989.

- Bradshaw, Ben (orally). BBC News, 12 November 1989. Quoted in August (1999), p. 198

- "We Were Told to Stop Trespassing at All Costs". Deutsche Welle. 2 November 2006.

- Adam (2005), p. 114

- Fröhling (2007), p. 183

- Nothnagle (1999), p. 17

- Nothnagle (1999), pp. 202–203

- Nothnagle (1999), p. 204

- Childs (2001), p. 90

- Childs (2001), p. 100

- Childs (2001), p. 105

- Childs (2001), p. 140

- Görtemaker, Manfred (2002). Kleine Geschichte der Bundesrepublik Deutschland (in German). C.H.Beck. pp. 373-373. ISBN 978-3-406-49538-0.

- Rottman (2008), p. 58

- Jackson, James O. (12 February 1990). "The Revolution Came From the People". Time.

- Koenig, Robert L. (22 April 1990). "Unity replaces fence — German social, economic barriers next to fall". St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

- Rottman, p. 61

- Freytag (1996), p. 230

- "Border "No Man's Land" Officially Declared Mine-Free". The Week in Germany. New York City: German Information Center. 13 May 1996. p. 13.

- Thorson, Larry (11 November 1995). "Former German border almost free of mines". Austin American-Statesman.

References

- Adam, Thomas (2005). Germany and the Americas: culture, politics, and history. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-628-2.

- August, Oliver (1999). Along the Wall and Watchtowers. London: Harper Collins. ISBN 0002570432.

- Berdahl, Daphne (1999). Where the world ended: re-unification and identity in the German borderland. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21477-3.

- Buchholz, Hanns (1994). "The Inner-German Border". In Grundy-Warr, Carl (ed.). Eurasia: World Boundaries Volume 3. World Boundaries (ed. Blake, Gerald H.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08834-8.

- Childs, David (2001). The fall of the GDR. London: Pearson Education Ltd. ISBN 0-582-31568-9.

- Cramer, Michael (2008). German-German Border Trail. Rodingersdorf: Esterbauer. ISBN 978-3-85000-254-7.

- Faringdon, Hugh (1986). Confrontation: the Strategic Geography of NATO and the Warsaw Pact. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Books. ISBN 0-7102-0676-3.

- Freytag, Konrad (1996). "Germany's Security Policy and the Role of Bundeswehr in the Post-Cold War Period". In Trifunovska, Snežana (ed.). The Transatlantic Alliance on the Eve of the New Millennium. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 978-90-411-0243-0.

- Fröhling, Wolf Amadeus (2007). Ick ooch: meine 20 Jahre DDR und die Folgen. Kampehl: Dosse. ISBN 978-3-9811279-3-5.

- Hertle, Hans-Hermann (2007). The Berlin Wall: Monument of the Cold War. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag. ISBN 978-3-86153-463-1.

- Jarausch, Konrad Hugo (1994). The rush to German unity. New York City: Oxford University Press US. ISBN 978-0-19-508577-8.

- Meyer, Michael (2009). The Year that Changed the World. New York City: Scribner. ISBN 978-1-4165-5845-3.

- Nothnagle, Alan L. (1990). Building the East German myth: historical mythology and youth propaganda in the German Democratic Republic. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-10946-4.

- Rottman, Gordon L. (2008). The Berlin Wall and the Intra-German border 1961–89. Fortress 69. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-193-9.

- Schweitzer, Carl Christoph (1995). Politics and government in Germany, 1944–1994: basic documents. Providence, RI: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-855-3.

- Sebasteyen, Victor (2009). Revolution 1989: the Fall of the Soviet Empire. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-85223-0.

- Shears, David (1970). The Ugly Frontier. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 94402.

- Stacy, William E. (1984). US Army Border Operations in Germany. US Army Military History Office. OCLC 53275935.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)