Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority

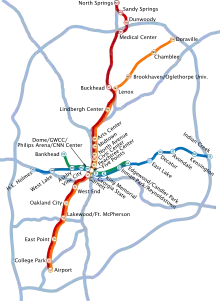

The Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA, /ˈmɑːrtə/) is the principal public transport operator in the Atlanta metropolitan area. Formed in 1971 as strictly a bus system, MARTA operates a network of bus routes linked to a rapid transit system consisting of 48 miles (77 km) of rail track with 38 train stations. MARTA's rapid transit system is the eighth-largest rapid transit system in the United States by ridership.

MARTA Rail System | |

System Map | |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Locale | Atlanta, Georgia |

| Transit type | Rapid transit Streetcar Bus |

| Number of lines | 4 (rail) 1 (streetcar) 100 (bus) |

| Number of stations | 38 (rail) 12 (streetcar) |

| Daily ridership | 432,900 (weekday; total)[1] 231,700 (weekday; rail) 199,000 (weekday; bus) 2,200 (weekday; paratransit) |

| Annual ridership | 134,701,300 (total)[1] 72,030,500 (rail) 62,021,700 (bus) 649,100 (paratransit) |

| Chief executive | Jeffrey A. Parker |

| Headquarters | 2424 Piedmont Road NE Atlanta, GA 30324 |

| Website | MARTA |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | February 17, 1972 (buses) June 30, 1979 (rail) |

| Operator(s) | Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority |

| Technical | |

| System length | 48 mi (77 km) |

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) standard gauge |

| Electrification | Third rail 750 V DC overhead lines |

| Top speed | 70 mph (110 km/h) |

MARTA operates almost exclusively in Fulton, Clayton, and DeKalb counties, although they maintain bus service to two destinations in neighboring Cobb County (Six Flags Over Georgia and the Cumberland Transfer Center next to the Cumberland Mall). MARTA also operates Mobility, a separate paratransit service for disabled customers. As of 2014, the average total daily ridership for the entire system (bus and rail) was 432,900 passengers.[1]

History

MARTA was originally proposed as a rapid transit agency for DeKalb, Fulton, Clayton, Gwinnett, and Cobb counties. These were the five original counties in the Atlanta metropolitan area, and to this day are the five largest counties in the region and state. MARTA was formed by an act of the Georgia General Assembly in 1965. In the same year, four of the five metropolitan area counties (Clayton, DeKalb, Fulton, and Gwinnett) and the City of Atlanta passed a referendum authorizing participation in the system, but the referendum failed in Cobb.

Although a 1968 referendum to actually fund MARTA failed, in 1971, voters in Fulton and DeKalb counties successfully passed a 1% sales tax increase to pay for MARTA operations, while Clayton and Gwinnett counties overwhelmingly rejected the tax in the referendum. Gwinnett County remains outside of the MARTA system. However, in November 2014, Clayton County voters passed a 1% sales tax to join the MARTA system, reversing its 1971 decision.[2] Also in 1971, the agency agreed to purchase the existing, bus-only Atlanta Transit Company; the sale of the company closed on February 17, 1972, giving the agency control over all public transit in the immediate Atlanta area.[3]

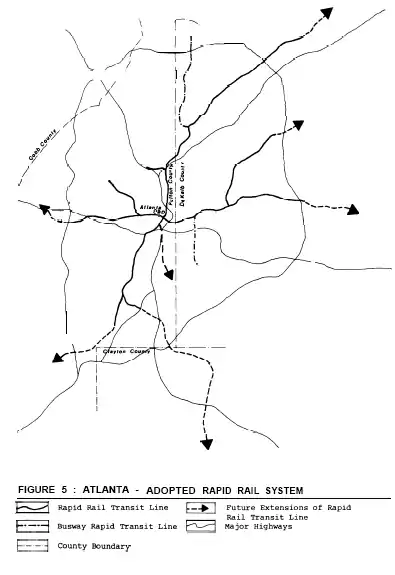

Construction began on MARTA's heavy rail system in 1975, with the first rail service commencing on June 30, 1979.[3] The system has since built most of the proposed rail lines, as well as stations in Dunwoody, Sandy Springs, and North Springs which were not included in the original plan. The missing rail segments from the original plan include a Tucker-North DeKalb line with service to Emory University and North Druid Hills, a Northwest line with service to Brookwood and Northside Drive, extension of the West line to Brownlee-Boulder Park near Fairburn Road, extension of the Proctor Creek line to West Highlands, and a branch off the south line to Hapeville and Clayton County.[4]

System

MARTA is composed of a heavy rail rapid transit system, a light rail system, and a bus system, all of which operate primarily within the boundaries of Fulton, Clayton and DeKalb counties. In addition to Atlanta itself, the transit agency serves various suburbs within its service area, including Alpharetta, Avondale Estates, Brookhaven, Chamblee, Clarkston, College Park, Decatur, Doraville, Dunwoody, East Point, Ellenwood, Fairburn, Forest Park, Hapeville, Jonesboro, Lake City, Lovejoy, Lithonia, Morrow, Palmetto, Riverdale, Roswell, Sandy Springs, Stone Mountain, and Union City. MARTA also serves the airport via a station located next to the main terminal. Although Cobb County is not part of the MARTA system, the agency operates one limited bus route to the Cumberland Boulevard Transfer Center and another to Six Flags Over Georgia.

MARTA allows bicycles on its trains, and buses have room for two bicycles on racks mounted on the front of the bus.[5] At the airport, bicycles can be locked up in all of the parking decks, so long as they are not obstructing either pedestrian or vehicular traffic.[6]

In 2007, MARTA had 4,729 full and part-time employees, of whom 1,719 were bus drivers or train operators.[7] Rail and bus operators, station agents, rail maintenance workers, and many other employees of MARTA are represented in negotiations by the Amalgamated Transit Union's Local 732.

Rapid transit

MARTA's rapid transit system has 47.6 miles (76.6 km) of route and 38 rail stations located on four lines: the Red Line (prior to October 2009, known as the North-South Line), Gold Line (former Northeast-South Line), Blue Line (former East-West Line), and Green Line (former Proctor Creek Line).[8][9] The tracks for this system are a combination of elevated, ground-level, and underground tracks.

The deepest station in the MARTA system is the Peachtree Center station, which is located in a hard-rock tunnel, 120 feet (37 m) beneath downtown Atlanta, where the highest hills in Atlanta are 1,100 feet (340 m) above sea level. No tunnel lining was installed in this station, or the adjacent tunnels. The architects and civil engineers decided to leave these with their rugged gneiss rock walls. The highest station in the MARTA system is the King Memorial station. It rises 90 feet (27 m) over a former CSX rail yard.

MARTA switched to a color-based identification system in October 2009. Formerly, the lines were named based upon their terminal stations, namely: Airport, Doraville, North Springs, H. E. Holmes, Bankhead, King Memorial, Candler Park, Indian Creek; or by their compass direction. During the transition between the two naming systems, all stations on the Red and Gold lines used their original orange signs, and all stations on the Blue and Green lines used their original blue signs.

All rapid transit lines have an ultimate nexus at the Five Points station, located in downtown Atlanta.[9] MARTA trains are operated using the Automatic Train Control system, with one human operator per train to make announcements, operate doors, and to operate the trains manually in case of a control system malfunction or an emergency. Many of the suburban stations have free daily and paid long-term parking in park and ride lots.[9] These stations also have designated Park and Ride passenger drop-off areas close to the stations' entrances.

Light rail

The Atlanta Streetcar is a modern streetcar route that is powered by an overhead line and operates in mixed vehicle traffic. The system was constructed by the City of Atlanta and was integrated into MARTA operations on July 1, 2018.[10][11] The streetcar operates on a 2.7-mile (4.3 km) pinched loop system in Downtown Atlanta.

Rolling stock

The Atlanta Streetcar system uses Siemens S70 light rail vehicles (LRVs).[12] A total of four S70 cars were purchased[13] and were built at two different facilities; the cars themselves were built in Sacramento, California while most other major components, like the propulsion system, were assembled at a plant about 30 miles north of Atlanta, in Alpharetta.[14][15] They were delivered in the first months of 2014 and are numbered 1001–1004.[16]

Bus

MARTA's bus system serves a wider area than the rail system, serving areas in Fulton, Clayton and DeKalb counties such as the cities of Roswell and Alpharetta in North Fulton, along with South DeKalb. MARTA bus service for Clayton County became effective March 21, 2015. As of 2010, MARTA has 554 diesel and compressed natural gas buses that covers over 110 bus routes which operated 25.9 million annual vehicle miles (41.7 million kilometers).[8] MARTA has one bus route providing limited service in Cobb County (Route 12 has been extended to Cobb County's Cumberland Boulevard Transfer Center). As of June 2016, MARTA purchased 18 New Flyer Industries, Xcelsior XN60.[17][18] All of the MARTA bus lines feed into or intersect MARTA rail lines as well. MARTA shuttle service is available to Six Flags Over Georgia during the park's summer season.

In addition to the free parking adjacent to many rail stations, MARTA also operates five park and ride lots serviced only by bus routes (Windward Parkway, Mansell Road, Stone Mountain, Barge Road, and South Fulton).[19]

Paratransit

In compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), MARTA provides the Mobility paratransit service for those persons defined as disabled by the ADA. MARTA uses 211 special lift-equipped vehicles for this service,[8] and can either deliver passengers to their final destination (curb-to-curb service) or can deliver the passenger to the closest accessible bus stop or rail station (feeder service). Mobility is limited to existing rail and bus routes and cannot extend more than a 0.75-mile (1.2 km) radius from any existing route. Mobility service is only provided during the hours of the fixed route servicing the area. An application for acceptance into the Mobility service is required; reservations are required for each trip. In fiscal year 2006, MARTA provided 289,258 Mobility trips.[20]

The average cost to MARTA for providing a one-way trip for an individual Mobility passenger is US$31.88.[21] This is much greater than the US$4.00 fare the Mobility rider is required to pay. The Americans with Disabilities Act forbids MARTA from charging a Mobility fare more than twice the normal fixed route fare.[22]

A 2001 federal civil lawsuit, Martin v. Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority, was brought by several disabled riders who alleged MARTA was violating the ADA by failing to provide: bus schedule and route information in an accessible format, buses with working wheelchair lifts, stop announcements on rail and bus routes, and adequate staff to schedule and provide on-time Mobility service. The district court ruled in 2002 that MARTA had violated the ADA and granted the plaintiffs an injunction requiring MARTA to improve service to the disabled.[23]

Fare structure and operation

Currently, the one-way full fare for MARTA costs US$2.50. New Breeze cards are $2. Breeze Tickets carry an extra fee of $1. Passengers over 65, passengers with disabilities and Medicare recipients are eligible to receive a discounted fare of $1. A one-way paratransit fare is $4. Ten full fare one-way trips can be purchased for $25, and twenty full fare trips can be purchased at a discount for $42.50. MARTA also offers unlimited travel through multiple transit pass options: 24-Hour pass $9, 2-day pass $14, 3-day pass $16, 4-day pass $19, 7-day pass $23.75, and a 30-day pass for $95. Additional discounted pass programs allow for university students and staff to purchase calendar monthly passes. Additional discounts are available to corporate partners who sell monthly MARTA passes to employees and also to groups and conventions visiting Atlanta. Some employers (at their own expense) also provide reduced cost or free MARTA passes to employees to encourage the use of public transportation. Children up to 46 inches (120 cm) can ride for free with fare-paying rider; limit is 2.

Free shuttles also operate within the MARTA area, but are not part of MARTA. The Buckhead Uptown Connection (The BUC) goes around Buckhead, Atlanta's uptown section and its third major business district behind downtown and midtown. This includes Lenox Square mall and the many high-rises and skyscrapers built along Peachtree Road. The Atlantic Station Shuttle offers service between the Arts Center MARTA Station and the Atlantic Station neighborhood of Midtown. Georgia Tech operates the Tech trolley between central campus, Technology Square, and the Midtown MARTA Station, as well as "Stinger" buses around its campus. Emory University operates "The Cliff" shuttle buses in and around its campus. The Clifton Corridor Transportation Management Association (CCTMA) operates a shuttle connecting Emory with downtown Decatur and the Decatur MARTA station.

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, in March 2020 MARTA introduced free fares to bus rides, which ended early September 2020. The free fare modification did not apply to rail fares.[24]

Breeze Card

MARTA finished implementing the "Breeze" smart card electronic fare collection system in September 2006, replacing the previous token-based fare collection system. The new Breeze Card allows riders to load money on the card for use over time, and to add unlimited day passes that are not fixed to a calendar period. The Breeze Card ($2) is for every passenger riding MARTA. The new Breeze fare gates are designed to help prevent fare evasion; with the older fare collection system fare evasion was much easier and was estimated to cost MARTA $10 million per year.[25] Other connecting transit systems such as GRTA Xpress and CCT also use the Breeze system.

MARTA stopped selling tokens after the Breeze conversion.[26] Cards (without fare) were sent by mail for free to those who requested them when the system was first implemented.

To protect against hacking problems experienced by the then-current Breeze Card, MARTA rolled out a new Breeze Card in January 2016. The new card costs $2.[27]

Hours of operation

MARTA operates every day. Rail service is provided from approximately 4:45 am to 1:00 am, Monday to Friday, and 6:00 am to 1:00 am on Saturday, Sunday & most holidays. During certain events (New Year's Eve) trains run until 2:00 a.m. (Trains also run all night during winter storms, though not in passenger service, to prevent ice from forming on non-underground lines.) On weekdays, trains run every 20 minutes on all rail lines from the beginning of service until 6:00 am. From 6:00 am-9:00 am and 3:00 pm-7:00 pm, trains run every 10 minutes on all rail lines. From 9:00 am-3:00 pm and 7:00 pm-8:30 pm, trains run every 12 minutes on all rail lines. From 8:30 pm until the end of service, trains run every 20 minutes on all rail lines. MARTA's Red Line rail service only operates between North Springs and Lindbergh Center stations after 8:30 pm. MARTA's Green Line rail service only operates between Bankhead and Vine City stations after 8:30 pm; Monday-Friday (with the exception of public holidays and track work performed by the authority). On weekends and public holidays, trains run every 20 minutes on all rail lines. Bus routes have varying frequencies dependent upon passenger demand.[28]

Fare reciprocity

Through formal fare reciprocity agreements, MARTA riders are able to transfer for free to the three other metro-Atlanta transit systems: Gwinnett County Transit, Cobb Community Transit and GRTA Xpress. Some of these agreements require that neither system have significantly more transfers than the other. MARTA has stated that this is the case, that inbound (to MARTA from another system) and outbound (from MARTA to another system) transfers are approximately equal (for second quarter 2006, 8888 daily passengers transferred inbound and 8843 transferred outbound).[29] Analysis of morning transfers (5 to 9 am) to MARTA shows that Cobb County had 718 inbound transfers but only 528 outbound, Gwinnett County had 239 inbound and 269 outbound, and GRTA Xpress had 1,175 inbound but 615 outbound.[29] Some have suggested that more people from the other systems may benefit from free transfers than those living in the MARTA service area. However, it has been noted that workers traveling in the morning to Atlanta from another system will more than likely make the return trip home, resulting in an equal number of transfers.

Funding

Sales tax

In addition to fare collections, the MARTA budget is funded by a 1% sales tax in Fulton, Clayton and DeKalb counties along with limited federal money. In 2017, the City of Atlanta raised their sales tax for MARTA to 1.5% to improve and expand MARTA. For fiscal year 2007, MARTA had a farebox recovery ratio of 31.8%.[7] By law, funds from the 1% sales tax must be split evenly between MARTA's operational and Capital expenditure budgets. This restriction does not apply to other sources of revenue, including passenger revenue.[30] The split was written into MARTA legislation at MARTA's formation with the rationale that MARTA should continue expanding and investing in the system. However, MARTA has no active rail construction projects. Capital funds continue to decrease every year, creating a shortfall. The operations funds limit the amount of service MARTA provides. The sales tax law was amended by the state legislature in 2002 to allow a temporary three-year 45% capital/55% operations split.[31] This additional 5% for operations expired in 2005. A 2005 bill to renew the split was tabled by the legislature's MARTA Oversight Committee, forcing MARTA to pass a new budget with cuts in service. The temporary 45%/55% capital/operations split was renewed again in the 2006 state legislative session. The capital funds surplus has resulted in projects, such as a new US$100 million Breeze Card fare collection system and US$1.1 million automatic toilets in the MARTA Five Points station, occurring at the same time that MARTA is struggling to pay for bus and rail operations. In 2015, the Georgia General Assembly approved a new bill that no longer requires MARTA to split the 1% Sales Tax. Due to low Sales Tax Revenue and no source of funding from the State of Georgia, MARTA was forced to eliminate 43 bus routes, eliminate shuttles, (Excluding the Six Flags Over Georgia and Braves Shuttle) and reduce Rail Service frequencies and hours. MARTA also closed the majority of its station restrooms. There are 13 station restrooms open to the public, which most are located at the end of each line including College Park, Arts Center, Peachtree Center, West End, Avondale, Kensington and Lindbergh Center. There are two Ridestores available. The two Ridestores are located at the Airport and Five Points Rail Stations. Despite the massive cuts, MARTA predicted the system would still come up 69.34 million dollars short for FY 2011; in which was pulled from their Reserved Account.[32] A $9 million addition was posted for 2013. This money is being re-invested into the system by adding frequency to trains and bus routes.

The current 1% sales tax was set to be reduced to 0.5% in 2032. In early 2007 MARTA made a request to the City of Atlanta, DeKalb County, and Fulton County to seek a 15-year extension of the 1% sales tax from 2032 to 2047, with a 0.5% sales tax from 2047 to 2057.[33] This is the fourth time in its history that MARTA sought the extension, the most recent in 1990.[34] MARTA said the commitment to the tax is needed for the agency to secure long-term financing in the form of bonds to pay for any future expansions to the system.[33] The resolution called for four new routes: bus rapid transit from H.E. Holmes station to Fulton Industrial Boulevard, bus rapid transit from Garnett station to Stonecrest Mall, transit for the BeltLine, and a direct transit link from Lindbergh Center to Emory University (formerly called the "C-Loop").[35] To approve the tax extension, two of the three government agencies needed to agree to the extension. In March 2007 the City of Atlanta voted 12–1 to approve the extension.[33] In April 2007 the DeKalb County Commission also approved the sales tax extension.[36] Some Fulton county officials opposed the sales tax extension on the basis that the proposed service expansions did not include previously proposed expansion of the North Rail line to Roswell and Alpharetta in North Fulton County.[37]

State funding controversy

MARTA was formed through the Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority Act of 1965, an act of the Georgia General Assembly. In addition to allowing the formation of the agency, and the collection of revenue from taxes, the legislation previously placed restrictions on how the agency managed its funds. In particular, the legislation established that any funds raised from the sale of bonds and capital goods would be spent on capital expenditures, and that any extra proceeds be put aside for paying off bond debt. While the enabling legislation put restrictions on how MARTA could manage its money, MARTA has never received any operational funding from the State of Georgia, making it the largest public transportation agency in the United States and the second-largest transit agency in Anglo-America (after the Toronto Transit Commission) not to receive state or provincial funding for operational expenses.[38] The funding restrictions on MARTA were removed in 2015, with the passage of House Bill 213 by the General Assembly.[39]

In early April 2009, MARTA experienced a budget crisis when the Georgia General Assembly failed to pass a bill that would allow MARTA to access its own capital reserve account, in order to compensate for a severe drop in sales-tax revenue during the late-2000s recession. MARTA stated that this could force the agency to discontinue operations one day out of the week, possibly a weekday. The agency's budget crisis forced MARTA to lay off 700 employees. Service cuts and other budget-stabilizing measures began in fiscal year 2011, with the first affected service mark-up in September 2010. Governor Sonny Perdue refused to call a special session as requested, and did not issue an executive order as he stated it would not be legal to do so.

Governance

MARTA is a multi-county authority that is governed by a board of directors, consisting of representatives appointed from the city of Atlanta (3 members), and the remainder of the counties of Fulton (3 members), Clayton (2 members) and DeKalb (4 members). Additionally, there is 1 member from the Georgia Department of Transportation, and 1 member from Georgia Regional Transportation Authority who also serve on the MARTA Board of Directors.[40]

Positions on the MARTA board are directly appointed by the organizations they represent. Although the state of Georgia does not contribute to MARTA's operational funding, it still has voting members on the MARTA board. A similar situation existed for both Clayton and Gwinnett counties during most of MARTA's history; as a consequence of passing the authorization referendum but not the funding referendum. Gwinnett County have representation on the MARTA Board of Directors without paying into the system. This situation became controversial in 2004 when Gwinnett's representative Mychal Walker was found to have accepted US$20,000 from a lobbyist trying to secure a US$100 million contract with MARTA. Despite the controversy, as well as a MARTA board ruling that Walker violated the MARTA ethics policy, the Gwinnett County Commission initially failed to remove Mr. Walker from his position on the MARTA Board. Eventually, the state legislature was called upon to change the law governing MARTA's Board to allow for the removal of a member whose appointing county did not act on a request for removal. Before the new law could be used, Mr. Walker was arrested on an unrelated child support violation, which resulted in his firing by the Gwinnett County Commission.

The highest position at MARTA is the general manager and chief executive officer. In October 2007, Dr. Beverly A. Scott was named the new general manager. Prior to joining MARTA, Dr. Scott served as GM/CEO of the Sacramento Regional Transit District. She has over 30 years of experience in the transportation industry. After 5 years at MARTA, she decided not to renew her contract with MARTA's Board of Directors. Scott's last day was December 9, 2012. Keith Parker was MARTA's General Manager/CEO from December 9, 2012 – October 11, 2017. Jeffrey A. Parker is MARTA's current General Manager/CEO.[41] Prior to Dr. Scott, MARTA's General Manager was Richard McCrillis from 2006 to 2007. In October 2007, McCrillis retired after 22 years of service at MARTA.[42]

The Georgia General Assembly has a standing committee that is charged with financial oversight of the agency. During the 2009 legislative session, Representative Jill Chambers,[43] the MARTOC chairperson at the time, introduced a bill that would place MARTA under GRTA, and permanently remove the requirement that MARTA split its expenditures 50/50 between capital and operations. This would allow MARTA to avoid service cuts at times when sales tax revenue is low due to recession, without having to ask the state legislature for temporary exemptions (typically a 55/45 split) as it has received before. The bill was not passed, but the funding restrictions were removed in 2015.

Performance and safety

During the 2005 fiscal year, MARTA had a customer satisfaction rate of 79%. On-time performance for rail service was 91.64%. The mean distance between rail service interruptions was 9,493 miles (15,278 km) and the mean distance between bus failures was 3,301 miles (5,312 km).[44]

MARTA has had two fatal accidents which resulted in a formal investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board. On February 25, 2000 a train near Avondale station struck two automatic train control technicians who were inspecting a relay box; one was fatally injured and the other technician suffered serious injuries. The workers had failed to apply for a safe clearance restriction for the track work. In addition, the rail system center controller, who was aware of the workers, failed to notify train drivers of the technicians' presence.[45] A second accident occurred on April 10, 2000 when a train struck a bucket lift containing two contract workers at Lenox station; the workers were fatally injured. Although the MARTA employee who was accompanying the workers notified the rail control center of the work over the track, the control center employee failed to block off the section of the track in the automated rail control system and also failed to notify the unscheduled southbound train of the workers' presence.[46] In 2001 MARTA settled with the families of the two killed workers for US$10.5 million.[47]

In addition to these accidents, MARTA trains have derailed five times in recent years. The most recent incident occurred in January 2019 when an out of service train derailed between Airport station and College Park station. The operator was not injured. A previous derailment occurred on December 4, 2006 Medical Center station when a train carrying passengers was moved over a rail switch. No injuries were reported.[48] In July 1996 during Atlanta's hosting of the Olympics, a paired car on a train which had developed mechanical problems was uncoupled from other cars at Indian Creek station (the last station on the east line). The train began rolling, crashing through the bumper at the end of the rail line and running off of the track. The train operator, the only person on board, received minor injuries.[49][50] In June 1996 a minor derailment occurred at the junction between the North and Northeast lines; MARTA estimated 150 people were aboard.[51] The derailment occurred when a rail supervisor told the train driver to reverse the train after realizing the train had gone the wrong way at a track split; a MARTA investigation of the incident showed the derailment caused $125,000 of damage to the train and track and caused injury to 16 passengers.[52] And in August 1994 a minor derailment occurred at a switch between Candler Park and Inman Park. Approximately 20 passengers were on board and no one was injured.[51]

On December 31, 2007 MARTA had three separate escalator accidents that injured at least 11 people. The incidents occurred as large crowds were going to the Chick-fil-A Bowl. Two escalators failed at Five Points station, and one escalator failed at Dome/GWCC/Philips Arena/CNN Center station. MARTA initially blamed the incidents on rowdy patrons jumping on the escalator.[53] However, a subsequent formal investigation showed that the braking systems and a weak motor were to blame for the incidents.[54]

In September 2008, a Fulton County jury awarded a woman $525,000 for injuries received in an accident at the Peachtree Center station. MARTA has been criticized for its escalator maintenance policies after recent injuries due to escalators overloading, but has discussed plans to improve its policies and regulate passenger loads with posted station agents.[55]

Expansion plans

Previous expansion plans

MARTA was built with at least three stubs for rail lines which were never built. The Northwest Line towards Cobb County has a stub tunnel east of Atlantic Station, but that redevelopment has not been built with a MARTA station in mind, and Cobb County would instead most likely get a light rail or commuter rail system (neither of which have been studied) or a bus rapid transit service (see Northwest Corridor HOV/BRT). The Northwest line was reduced to two planned stations but was later dropped entirely.

The South Line's branch to Hapeville was considered for extension into Clayton County as far away as Forest Park, but this idea was also cut off when the voters of that county initially refused to approve tax funding for the line. Another idea for a rail spur line spur was for an above-ground line from near the International Airport for a spur line to the town of Hapeville, but no work has been initiated. The idea to revive expansion plans in the form of heavy rail and bus was approved to go once again before voters in November 2014 by the Clayton county commissioners in July 2014 with a 1% sales tax providing the funding for said expansion. This time, the referendum was approved and Clayton County voted to join MARTA, the system's first ever expansion outside of Fulton, Dekalb and the city of Atlanta.

Yet another proposed spur line would have branched off the Blue Line in DeKalb County, running northeast to the area of North Druid Hills, Emory University, and the town of Tucker. Now under consideration is an idea for light rail line (rather than heavy rail) from Avondale Station to Lindbergh Center, via Emory/CDC.

The Northeast Line of the rail system, which has ended in Doraville for two decades, was considered for extension into Gwinnett County as far as northeast as Norcross, Georgia, but this idea was cut off when the voters of that county declined to approve sales-tax funding for it.

The Proctor Creek branch was also projected to go one more station northwestward to the West Highlands neighborhood, but no work has been done on that one either.[56]

Expansion westward to Fulton Industrial Boulevard through the use of either heavy rail extension or bus rapid transit has been proposed as an extension of the West Line since the system was originally planned.[57]

The final three MARTA rail stations to be built, Dunwoody, Sandy Springs and North Springs - all north of the Interstate 285 Perimeter, were opened in 2000. The tracks to those stations were run on the surface of the median strip of Georgia 400 which was constructed just east of the Buckhead area as a tollway during the early 1990s. This is one of just two places at which the MARTA rail system extends outside of Interstate 285. The other is at the Indian Creek Station in eastern DeKalb County.

From 2000–Present, there have been no active railway expansion projects in the MARTA system due to lack of additional sales-tax funding, the need to spend its limited capital budget on refurbishing its older rolling stock, replacing the fare-collection system, repairing the tracks and their electrical systems, and other long-term maintenance, repair, and operations requirements.

Mall at Stonecrest Expansion

Eastward expansion focuses on bus rapid transit from downtown Atlanta along I-20 and extension of heavy rail transit from Indian Creek station, south along I-285 to I-20, then east along the I-20 corridor to the Mall at Stonecrest. The current Green Line would also be extended east from its current terminus at Edgewood/Candler Park station to Mall at Stonecrest.[58]

Memorial Drive BRT

Currently the only recent expansion in the entire MARTA system was the development of bus rapid transit along Memorial Drive from Kensington Station to the Goldsmith Road MARTA park and ride lot in Stone Mountain and Ponce De Leon Avenue. (Bus Service started operating on September 27, 2010). The bus had two routes: The Q Express runs between MARTA's Kensington Station and a free 150-car Park-and-Ride lot at Goldsmith Road & Memorial Drive; The Express only stops twice along the way at North Hairston Road and again at Georgia Perimeter College.

The Q Limited also ran north along Memorial Drive from Kensington Station but branched off at North Hairston Road on the way to East Ponce de Leon Avenue. The Q Limited had four stops along the way in addition the same stops for the Express The implementation of revenue-collecting service had initially been planned for early 2009.[59]

Due to low ridership, BRT service was discontinued.

Atlanta BeltLine

Additionally, several traffic corridors are currently being studied by MARTA for possible system expansion. The BeltLine is a current proposal for the use of light rail and possibly bus or streetcar service on existing railroad rights-of-way around Atlanta's central business districts.[60] The conversion of existing rail right-of-way to the proposed BeltLine also calls for the creation of three additional MARTA rapid transit stations where existing lines intersect the Belt Line at Simpson Road, Hulsey Yard, and Murphy Crossing.

Clifton Corridor

Rapid transit alternatives are as of October 2011, under consideration for the Clifton Corridor, from Lindbergh Center, following the CSX rail corridor to Emory University and the Centers for Disease Control, with possible continuation along the northern edge of Decatur on to Avondale MARTA station. Bus, light rail and heavy rail rapid-transit options had been considered,[61] with light rail being selected as the preferred option.[62]

Connect 400

The Georgia 400 Transit Initiative (also known as "Connect 400") is a MARTA project to study options for expanding high-capacity transit along the Georgia State Route 400 corridor into the northern reaches of Fulton county.[63][64] The initiative, kicked off in December 2011, envisages an 11.9-mile extension of rapid transit service, starting in the south at North Springs Transit Station, the current terminus of the existing MARTA Red Line. From there, such an extension would continue northward through the cities of Sandy Springs, Roswell, and Alpharetta, terminating in the vicinity of Windward Parkway.

As of the fifth public meeting on the subject on September 26, 2013, the study had narrowed the field of transit technology alternatives to three, all using existing right-of-way along SR 400: heavy-rail transit (HRT, extending the Red Line northward), light-rail transit (LRT), or bus rapid transit (BRT). Early designs for all three options include stations near Northridge Road, Holcomb Bridge Road, Mansell Road, North Point Mall, and Windward Parkway; initial sketches of the LRT and BRT options also include a station near Old Milton Parkway.[65]

As of June 2015,[66] the project is moving into the Environmental Impact study stage of the planning process. According to MARTA Representatives at the April 2015 meetings, the expansion could open in 2025 at the earliest assuming a best-case scenario. Federal funding is still not approved; the Environmental Impact study must be complete. By the April 2015 meeting, the LRT option has been discarded. The HRT option has been approved as the Locally Preferred Alternative,[67] though two BRT options exist - one that would run in a dedicated bus guideway and the other to integrate with Georgia DOT's planned work for the corridor. The GDOT integrated option would include sharing normal traffic lanes at least in some parts of the route. The plans for stations at Mansell Rd. and Haynes Bridge Rd. have been merged into one station at North Point Mall.

Proposed new infill stations

Adding another station to the existing line near Armour Yard (MARTA's main railyard, opened 2005) has also been discussed, as the Red and Gold MARTA lines, the northeast BeltLine light rail, proposed commuter rail lines to points northeast such as Athens (the "Brain Train") and Gainesville, would all pass through Armour Yard. Other stations that have been proposed are; Mechanicsville, Boone, Murphy Crossing, and Krog.

The proposed Atlanta Multimodal Passenger Terminal (MMPT) would be built next to Five Points station, connecting MARTA to surface passenger rail, including commuter rail, future intercity rail, Amtrak, and possible high-speed rail in the Southeast Corridor.

Additional expansion plans for MARTA and other metro Atlanta transportation agencies are detailed in Mobility 2030 a timeline by the Atlanta Regional Commission for improving transit through the year 2030.

Clayton County

On July 5, 2014, the Clayton County Board of Commissioners, by a margin of 3-1 (Jeff Turner, Shana Rooks, and Sonna Gregory voting in favor,) approved a contract with MARTA to extend service to the county, financed by a 1 percent sales tax. Fulton and DeKalb county leaders approved the expansion. On November 4, 2014, Clayton County residents approved the 1% sales tax to join MARTA. Bus Service was implemented on March 21, 2015. The contract also includes provisions for future rail transit to the county by 2025.[68]

One high-capacity/rail proposal calls for stations at Hapeville, Mountain View/ATL Hartsfield International Terminal, Forest Park, Fort Gillem, Clayton State/Morrow, Morrow/Southlake and Jonesboro by 2022. A station at Lovejoy is also proposed, which would open as a later phase.[69] In 2018, commuter rail was selected as the locally preferred alternative of transit mode along the corridor.[70]

Gwinnett County

In September 2018, MARTA's Board of Directors and the Gwinnett County Board of Commissioners gave conditional approval to an agreement which would see MARTA assume, and significantly expand, operations of Gwinnett's bus system (in operation since 2001) and clear the way for the long-sought-after extension of MARTA's rail system into the county from its current terminus at Doraville. The population of Gwinnett County has significantly increased, and become more racially and ethnically diverse, since 1990, the last time the county rejected joining MARTA. Whereas white business elites were the initial demographic to support the MARTA in 1965, most black voters had voted to fund transit. However, large communities of rural white Georgians opposed MARTA.[71]

The original plan in 2018 includes a detailed multi-year plan to expand heavy rail rapid transit in Gwinnett County. Some aspects of the Connect Gwinnett plan will include a train that runs every ten minutes, and also get more buses to take people to the MARTA station. This was possible because Georgia Legislature permitted counties to raise taxes to fund transit, which before was not allowed.[72] The contract with MARTA would go into effect only if a public vote, that was scheduled for March 19, 2019, succeeded. The agreement called for a new one-cent sales tax that would be collected in Gwinnett County until 2057.[73] On March 19, 2019, the third transit referendum failed, with 54.32% of the vote being "No" to expand.[74] Gwinnett County Commissioner Charlotte Nash stated that she would possibly try again in the future for another referendum, probably during an election cycle with a bigger turnout.

Criticism and concern

Criticism of MARTA has originated from many different groups. Opponents of MARTA are critical of MARTA's perceived inefficiency and alleged wasteful spending. Supporters of MARTA are critical of the almost complete lack of state and regional support of MARTA. In recent years, additional concerns have been raised regarding the reliability of service, as well as the governing structure of MARTA.

Lack of regional financial support

Since the formation of MARTA, the Georgia state government has never contributed to MARTA operational funding. Currently, MARTA is the largest mass transportation system in the United States not to receive state funding.[38] Revenue from the Georgia motor fuel tax is currently restricted to roads and bridges and cannot be used for public transportation, further complicating potential sources of state funding for MARTA.[2] In addition, the other largest two suburban counties (Gwinnett and Cobb counties) have refused to join or fund MARTA. Both Gwinnett and Clayton counties initially agreed to join MARTA but refused MARTA rail and bus service when voters in their respective counties voted against paying to help fund the system. Clayton County finally joined MARTA in November 2014; Gwinnett is planning a referendum in March 2019 to see if residents want to join. Gwinnett, along with Cobb County, created independent bus transit: Cobb Community Transit on July 10, 1989,[75] Gwinnett County Transit on November 5, 2001.[76] A separate regional bus transit service, Xpress, is operated by the Georgia Regional Transportation Authority in partnership with 11 metro Atlanta counties including Fulton and DeKalb, and began service on June 6, 2004.[77]

The MARTA Board members are criticized for not being regular users of MARTA and thus are not actually aware of the concerns of MARTA commuters. Former CEO, Keith Parker, was known for commuting daily from Dunwoody to the headquarters using the Red Line.

Due to no funding from the state of Georgia and its limited funding from Fulton, Clayton and DeKalb counties, MARTA has struggled for many years to provide adequate service to the metropolitan area. As a result, MARTA has gained a notorious reputation throughout the metro Atlanta area for being ineffective and inconvenient.[38] Many people who own cars avoid using the system altogether while residents in suburban areas usually drive their car to a MARTA rail station (instead of using bus service) if their job is near an adjacent one. MARTA's financial structure (being tied to a 1% sales tax) has forced the agency to cut services during times of economic depression, further resulting in complaints about the inconvenience and inadequacy of MARTA services.[38]

Although surrounding counties do not pay for MARTA, many of their residents use MARTA by driving directly to a MARTA station or by using a county or regional bus system which connects to MARTA. A license plate study from 1988 to 1997 showed that 44% of the cars parked in MARTA park-and-ride lots were from outside of Fulton and DeKalb counties.[2] Current fare reciprocity agreements also allow non-paying counties to provide bus service for their residents which provide free connections to MARTA (see Fare reciprocity). According to a 2000 MARTA ridership study, 12% of MARTA riders live outside of MARTA's service area.[76]

Effects of race on expansion and funding

It is often argued that racial politics also play a role in the operation and future service planning for MARTA. Opponents of Georgia's transportation policies have alleged a race-based two-tiered system, where billions are spent by the state on highway expansion to aid the automobile commutes of mostly White residents of the suburbs and rural areas (like GRIP), while service cuts at MARTA have hurt mostly African Americans in low-income areas where residents cannot afford automobile ownership.[38] Proponents contest that a portion of state funding for highways comes from the gasoline tax, a user fee analogous to the fare MARTA riders pay. Supporters of MARTA have alleged that the lack of participation by other metro Atlanta counties is rooted in racism and classism.[38][78] In 1987, David Chesnut, then chairman of MARTA, stated, "The development of a regional transit system in the Atlanta area is being held hostage to race, and I think it's high time we admitted it and talked about it."[79] As part of its Title VI plan, MARTA data revealed that 75 percent of MARTA riders were Black in 2015.[80] MARTA is sometimes sarcastically said to stand for "Moving Africans Rapidly Through Atlanta", a replacement backronym, due to the relatively low number of white riders, particularly after peak commuting hours.[81][82]

Criminal activity

Despite a strong safety record, throughout MARTA's history there have been continued concerns regarding criminal activity on MARTA trains and in and around MARTA train stations. In the aftermath of a 1985 aggravated assault against the daughter of a Georgia State University professor, complaints were made that MARTA was underreporting its annual crime statistics. A 1986 review of the previous year's records by MARTA's audit office and the state legislature's MARTA Oversight Committee (MARTOC) showed no deliberate underreporting of crime, but rather over-reporting of crime because MARTA included crimes not related to the rail line and did not adhere to the Uniform Crime Reporting system (reporting multiple crimes by the same person instead of only the most serious crime).[83]

According to Federal Transit Administration records, MARTA's crime statistics are in line with those of similar-sized systems, such as Bay Area Rapid Transit in the San Francisco Bay area.[84] However, high-profile crimes on or near MARTA have created the impression with some that MARTA is unsafe and lacks a strong police presence, even though it has its own police department.[84] From 2005 to 2009, two homicides and one rape were reported on MARTA property. The most common crime reported was larceny. The most common area for crime was MARTA's rail service, followed by MARTA's parking lots. For fiscal year 2009, MARTA had a crime rate of 3.09 per 1 million riders, with 483 crimes reported during the entire year.[85]

Suburban counties have opposed expanding MARTA on the basis that it would lead to increased crime, as well as the cost of expansion and the lack of perceived necessity to areas currently outside MARTA transit. It is alleged that because MARTA's service area includes some of Atlanta's most economically depressed and high-crime neighborhoods, expansion of MARTA would supposedly allow crime to spread to suburban areas. MARTA CEO, Dr. Scott, has acknowledged that assumption and cites a study that did not find transit systems to nucleate crime. Other counterarguments often cite the case of the Washington Metro, which provides services in economically depressed areas with limited problems in suburban Washington D.C. stops.[86]

Reliability of service

As is typical of rail transit in the United States, MARTA's rail lines have two parallel tracks. Any train failure or track work results in shared use of the other track by trains going opposite directions, a situation known as single-tracking.[87] There are no plans at this time to expand the number of tracks. MARTA is currently nearing the end of a complete replacement of tracks on all rail lines. Over the past few years, this replacement work has caused the agency to implement single-tracking on the weekends, which in turn has caused weekend patrons to experience less-frequent service.[88]

In the summer of 2006, as a result of unusually high summertime temperatures, many MARTA rail cars became overheated, damaging on-board propulsion equipment. As a result, many trains broke down and had to be taken out of service for repair. This was further compounded by the fact that at any given time up to 50 older rail cars were out of service as part of MARTA's rail car rehabilitation project. To compensate for the reduced number of operating rail cars, MARTA shortened trains from six to four cars in length. This sometimes resulted in almost half of the trains being shortened, creating crowded conditions for passengers.[89]

Misuse of funds by employees for personal expenses

In 2006 internal and external audits of MARTA corporate spending revealed personal charges on a pair of MARTA credit cards used by former General Manager and CEO Nathaniel Ford and two of his secretaries.[90] Ford's charges included $454 at a golf pro shop, $335 in clothing from Men's Wearhouse and a $58 visit to the dentist.[90] In response to the 2006 audit, Ford sent MARTA a check for $1,000 as reimbursement for the charges.[90] An additional credit card with charges involving two of his secretaries, Iris Anthony and Stephannie Smart, was also uncovered. Smart used the cards to pay approximately $6,000 in private expenses, and subsequently agreed to repay this amount to MARTA.[90]

Incidents

On October 15, 2011, 19-year-old Joetavius Stafford was killed by a MARTA police officer at the Vine City rail station. MARTA claims that Stafford was armed while his brother said he was unarmed. After a full investigation, there was evidence that Stafford was armed and the MPO was cleared.[91][92]

In June 2018, a MARTA contractor died after being struck by a train while working on the tracks between Buckhead and North Springs stations.[93]

References

- "Public Transportation Ridership Report" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. March 2016.

- Bullard, R. D.; et al. (2000). Sprawl City: Race, Politics, and Planning in Atlanta. Washington, D.C.: Island Press. pp. 52–59. ISBN 1-55963-790-0.

- "History of MARTA - 1970-1979". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- Ferreira, Robert. "MARTA Provisions for Future Extensions". world.nysubway.org. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Bikes on MARTA". Archived from the original on July 11, 2009.

- Information collected from Parking Division at (404)209-2945, Parking Operations at (404)530-67254, and Airport Police at (404)530-6800.

- "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. June 30, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Comprehensive Annual Financial Report" (PDF). Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. June 30, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "MARTA - Getting There - Rail Schedules and Map". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- King, Michael (July 1, 2018). "MARTA officially assumes operations of Atlanta Streetcar". 11Alive. Retrieved July 1, 2018.

- "MARTA officially takes over Atlanta Streetcar operations".

- "Fact Sheet" (PDF). Atlanta Streetcar. July 2013. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 31, 2017. Retrieved July 1, 2014.

- "Atlanta meets New Year deadline: Streetcars return to the streets of Georgia after a 65-year break". Tramways & Urban Transit. UK: LRTA Publishing. February 2015. p. 53.

- "Siemens to build Atlanta streetcars". Atlanta Business Chronicle. American City Business Journals. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- "Siemens is supplying Atlanta with the American type S70 LRT vehicles". Siemens.com. Siemens. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- "Worldwide Review (regular news section)". Tramways & Urban Transit. UK: LRTA Publishing. April 2014. p. 175.

- "MARTA's Bus Route 12 will provide extended service to the Cumberland Mall area" (Press release). Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. November 20, 2006. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Route 12 - Howell Mill". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Parking Information". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Fiscal Year 2006 Annual Report" (PDF). Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. June 30, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 15, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Georgia Governor's Council on Developmental Disabilities Five Year Strategic Plan". Georgia Governor's Council on Developmental Disabilities. Archived from the original (RTF) on February 24, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Part 37—Transportation Services for Individuals with Disabilities". Federal Transit Administration. October 1, 2005. Archived from the original on September 17, 2008. Retrieved February 24, 2008. Sec. 37.131 (c) Service criteria for complementary Mobility.

- Martin v Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Administration Archived April 4, 2015, at the Wayback Machine, No. 1:01-CV-3255-TWT (United States District Court for the Northern District of Georgia Atlanta Division). Retrieved on February 24, 2008.

- https://www.itsmarta.com/MARTA-service-modifications.aspx

- Donsky, Paul (February 22, 2006). "MARTA Plugs Gap in New Station Gates". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. p. 4B.

- "Frequently Asked Questions". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on March 12, 2008. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- Shamma, Tasnim (August 19, 2015). "MARTA Breeze Cards Will Double In Price Starting January". WABE. Retrieved September 20, 2015.

- "Hours of Operation". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on March 30, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- "Minutes of the Board of Directors Customer Development Committee". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. March 20, 2006. Archived from the original (DOC) on October 17, 2006. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "FY06 MARTOC Report" (PDF). Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. August 15, 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "History of MARTA - 2000-Present". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- Donsky, Paul (July 19, 2006). "MARTA flushes in new era with 12 self-cleaning toilets". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Donsky, Paul (March 29, 2007). "Atlanta votes to extend sales tax for MARTA". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Donsky, Paul (March 28, 2007). "Atlanta extends MARTA sales tax to 2047: Agency seeks extension approval from governments". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Donsky, Paul (March 26, 2007). "Atlanta council plans special meeting for vote on MARTA tax". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Donsky, Paul (April 25, 2007). "MARTA wins tax extension: Next stop could be new bus, rail lines". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Donsky, Paul (April 4, 2007). "Northside may balk on MARTA tax". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Wall, Michael (April 19, 2006). "Waiting for a ride: The racial reality behind MARTA's downward spiral". Creative Loafing. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "HB173". Georgia General Assembly. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- "Meet The Board". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on August 13, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- "Dr. Scott's Biography". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on June 24, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- "MARTA Monthly MARTA Thanks General Manager Richard McCrillis for 22 Years of Dedicated Service and Leadership". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. October 20, 2007. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved January 15, 2008.

- "MARTOC". Georgia General Assembly. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved March 2, 2008.

- "Fiscal Year 2005 Annual Report" (PDF). Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. June 30, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 3, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) train 103 striking technicians fouling the track Near MARTA Avondale Station in Decatur, Georgia February 25, 2000" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. August 8, 2003. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) Unscheduled train 166 striking bucket of self-propelled lift containing two contract workers MARTA Lenox rail transit station in Atlanta, Georgia April 10, 2000, about 2:30 am" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. August 8, 2003. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- Ippolito, Milo (December 5, 2001). "MARTA pays $10.5 million in workers' deaths". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Donsky; Morris (December 4, 2006). "MARTA back on track after derailment". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Monroe, Doug (July 25, 1996). "MARTA driver injured when two cars derail". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- "ATLANTA DAY 7;Atlanta Train Misses Station". The New York Times. July 26, 1996. Retrieved February 9, 2008.

- Kim, Lilian (June 2, 1996). "MARTA officials say accident a 'fluke'". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Goldberg, David (June 18, 1996). "Derailment probe cites bad decisions; Three MARTA employees were suspended and two managers face disciplinary action as a final report confirms MARTA's explanation that 'human error' was to blame". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Visser, Steve (December 31, 2007). "MARTA escalator accident blamed on rowdies". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Visser, Steve (January 11, 2008). "MARTA blames brakes and weak motor for escalator accidents". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- "MARTA escalator failures were mechanical". Retrieved September 16, 2008.

- MARTA Provisions. world.nycsubway.org. Retrieved on August 16, 2013.

- "West Line Corridor Details". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "I-20 East Corridor Details". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Memorial Drive Arterial Bus Rapid Transit". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "Beltline Corridor Details". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- MARTA Clifton Corridor Archived January 24, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Light Rail Transit Recommended for the Clifton Corridor - Annals of Transportation - Curbed Atlanta. Atlanta.curbed.com (March 22, 2012). Retrieved on 2013-08-16.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on November 25, 2015. Retrieved November 24, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- MARTA, Connect 400. "September 26, 2013 Presentation" (PDF). MARTA Ga 400 Corridor Presentations. MARTA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 29, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- MARTA, Connect 400. "Connect 400 Newsletter #3: September 2013" (PDF). MARTA Ga 400 Corridor Newsletters. MARTA. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 22, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 1, 2015. Retrieved July 22, 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- ""Connect 400" Transit Initiative Moves Forward". April 9, 2015.

- John Ruch (July 5, 2014). "Clayton approves MARTA contract for November ballot". Creative Loafing Atlanta. Retrieved July 5, 2014.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 12, 2014. Retrieved November 12, 2014.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Saporta, Maria (July 13, 2018). "Commuter rail is MARTA's choice for Clayton County". Atlanta Business Journal. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- "How Racial Discrimination Shaped Atlanta's Transportation Mess". Streetsblog USA. February 8, 2017. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- "Connect Gwinnett: Transit Plan | Gwinnett County". www.gwinnettcounty.com. Retrieved December 5, 2020.

- Estep, Tyler (September 6, 2018). "MARTA board approves historic Gwinnett contract". The Atlanta Journal-Constitution (ajc.com). Retrieved September 12, 2018.

- Curt Yeomans. "Gwinnett back at square one after MARTA rejected in key vote". Gwinnett Daily Post. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- "Cobb Community Transit (CCT) History". Cobb County Department of Transportation. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- "Task 1.2 Existing Transit Service Inventory" (PDF). Regional Transit Action Plan Technical Memorandum Number 2. Manuel Padron & Associates, Inc. and URS, Inc. April 30, 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2008. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- "About Xpress". Georgia Regional Transportation Authority. Retrieved February 29, 2008.

- "Atlanta weighing transit expansion". The New York Times. August 13, 1989. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- Schmidt, William (July 22, 1987). "Racial roadblock seen in Atlanta transit system". The New York Times. Retrieved February 27, 2008.

- "Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority Title VI Program Update June 2016 - 2019" (PDF). Itsmarta.com. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- McCosh, John (February 11, 2001). "MARTA calls on marketers for image aid; Can soft drinks fill empty seats?". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Torres, Angel O.; Bullard, Robert D.; Johnson, Glenn D. (2004). Highway robbery: transportation racism & new routes to equity. Boston: South End Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-89608-704-2.

- Harris, Karen (May 30, 1986). "MARTA over-reporting its crimes, legislative audit finds". The Atlanta Journal.

- Donskey, Paul; Daniels, Cynthia (February 9, 2007). "MARTA: HOW SAFE? Transit system officials defend security, cite low crime totals, despite a few high-profile incidents". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- "MARTA Police: Crime Stats". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- Firestone, David (April 8, 2002). "Overcoming a Taboo, Buses Will Now Serve Suburban Atlanta". The New York Times. Retrieved February 24, 2008.

- "We're Building a Better Way". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on October 17, 2006. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- "MARTA Track Renovation Information". Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. Archived from the original on June 29, 2007. Retrieved February 25, 2008.

- Donsky, Paul (September 12, 2006). "MARTA riders crowd heat-diminished fleet". Atlanta Journal-Constitution.

- Mahoney, Ryan (August 18, 2006). "Ex-MARTA CEO abused credit cards". Atlanta Business Chronicle. Retrieved October 27, 2006.

- Steve Visser (October 17, 2011). "MARTA: Dead teen was armed" The Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Accessed October 26, 2011.

- Steve Visser (October 20, 2011). "Forensic evidence little help in investigation of MARTA shooting" The Atlanta-Journal Constitution. Accessed October 26, 2011.

- Adrianne Haney (June 13, 2018). "MARTA contractor struck by train Sunday night has died" 11-Alive. Accessed March 12, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority. |

- MARTA website

- MARTA Breeze website

- New Georgia Encyclopedia article

- Georgia Regional Transportation Authority website

- Clayton County C-TRAN website

- Cobb Community Transit website

- Gwinnett County Transit website

- nycsubway.org Atlanta page

- Assessing Electoral Defeat - New Directions and Values for MARTA

- The Clueless Commuter's Guide to MARTA

- Citizens for Progressive Transportation - Atlanta Chapter

- Railfanning.org: MARTA Profile

- MARTA rail lines integrated with google maps

- 5 Points Station Map

- Atlanta Magazine - Where It All Went Wrong

- Martin Stupich Photographs, 1977-1978 of the development of MARTA from the Atlanta History Center

- Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit Authority (MARTA) Collection from Georgia State University