Battle of Atlanta

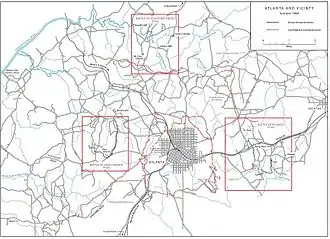

The Battle of Atlanta was a battle of the Atlanta Campaign fought during the American Civil War on July 22, 1864, just southeast of Atlanta, Georgia. Continuing their summer campaign to seize the important rail and supply hub of Atlanta, Union forces commanded by William Tecumseh Sherman overwhelmed and defeated Confederate forces defending the city under John Bell Hood. Union Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson was killed during the battle. Despite the implication of finality in its name, the battle occurred midway through the campaign, and the city did not fall until September 2, 1864, after a Union siege and various attempts to seize railroads and supply lines leading to Atlanta. After taking the city, Sherman's troops headed south-southeastward toward Milledgeville, the state capital, and on to Savannah with the March to the Sea.

| Battle of Atlanta | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Civil War | |||||||

Battle of Atlanta, by Kurz and Allison (1888) | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

William T. Sherman[1] James B. McPherson † |

John Bell Hood[1] William J. Hardee[1] | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

| Army of Tennessee[1] | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 34,863[2] | 40,438[2] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,641[3] | 5,500, at least 1,000 killed[4] | ||||||

The fall of Atlanta was especially noteworthy for its political ramifications. In the 1864 election, former Union general George B. McClellan, a Democrat, ran against President Lincoln, on a peace platform calling for an armistice with the Confederacy. The capture of Atlanta and Hood's burning of military facilities as he evacuated were extensively covered by Northern newspapers, significantly boosting Northern morale, and Lincoln was re-elected by a significant margin.

Background

In the Atlanta Campaign, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman commanded the Union forces of the Western Theater. The main Union force in the battle was the Army of the Tennessee, under Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson. He was one of the favorite commanders of Sherman and Ulysses Grant by being very quick and aggressive. Within Sherman's army, the XV Corps was commanded by Maj. Gen. John A. Logan,[5] the XVI Corps was commanded by Maj. Gen. Grenville M. Dodge, and Maj. Gen. Frank P. Blair Jr. commanded the XVII Corps.[6]

During the months leading up to the battle, Confederate Gen. Joseph E. Johnston had repeatedly retreated from Sherman's superior force. All along the Western and Atlantic Railroad line, from Chattanooga, Tennessee, to Marietta, Georgia, a pattern was played and replayed: Johnston took up a defensive position, Sherman marched to outflank the Confederate defenses, and Johnston retreated again. After Johnston's withdrawal following the Battle of Resaca, the two armies clashed again at the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, but the Confederate senior leadership in Richmond was unhappy with Johnston's perceived reluctance to fight the Union army, even though he had little chance of winning. Thus, on July 17, as he was preparing for the Battle of Peachtree Creek, Johnston was relieved of his command and replaced by Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood.[7] The dismissal and replacement of Johnston remains one of the most controversial decisions of the civil war.[8] Hood, who was fond of taking risks,[7] lashed out at Sherman's army at Peachtree Creek, but the attack failed, with more than 2500 Confederate casualties.[9]

Hood needed to defend the city of Atlanta, which was an important rail hub and industrial center for the Confederacy, but his army was small in comparison to the armies that Sherman commanded. He decided to withdraw, classically threatening Sherman's supply lines in his army's rear. Hood hoped his aggressiveness and the size of his still formidable force on-the-move would entice the Union troops to come forward against him, if only to protect their rear supply lines. The Union did not do so. McPherson's army closed in upon Decatur, Georgia, to the east side of Atlanta. Twice more in later campaigns, Hood would seek to lure the thrust of a Union axis of advance upon a position and/or force that he was commanding to seek an engagement. The Union's forces were not turned in those cases either.

William T. Sherman, USA

John B. Hood, CSA

Opposing Forces

Battle

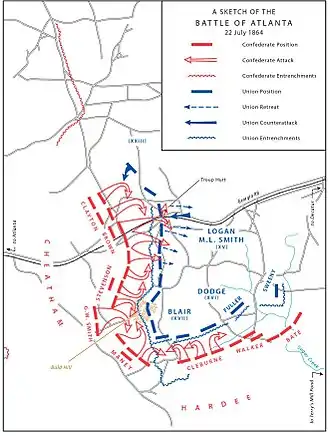

Meanwhile, Hood ordered Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee's corps on a march around the Union left flank, had Maj. Gen. Joseph Wheeler's cavalry march near Sherman's supply line, and had Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham's corps attack the Union front. However, it took longer than expected for Hardee to get his men into position, and, during that time, McPherson had correctly deduced a possible threat to his left flank, and sent XVI Corps, his reserve, to help strengthen it.[1] Hardee's men met this other force, and the battle began. Although the initial Confederate attack was repulsed, the Union left flank began to retreat. About this time, McPherson, who had ridden to the front to observe the battle, was shot and killed by Confederate infantry.[10] Confederate Maj. Gen. William H.T. Walker was also killed, shot from his horse by a Union picket.

Near Decatur, Brig. Gen. John W. Sprague, in command of the 2nd Brigade, 4th Division of the XVI Corps,[11] was attacked by Wheeler's cavalry. Wheeler had taken the Fayetteville Road, while Hardee's column took the Flat Shoals Road toward McPherson's position. The Federals fled the town in a stampede, but managed to save the ordnance and supply trains of the XV, XVI, XVII, and XX corps. With the failure of Hardee's assault, Wheeler was in no position to hold Decatur, and fell back to Atlanta that night.[12] Sprague was later awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions.[13]

The main lines of battle now formed an "L" shape, with Hardee's attack forming the lower part of the "L," and Cheatham's attack on the Union front as the vertical member of the "L". Hood intended to attack the Union troops from both east and west. The fighting centered on a hill east of the city known as Bald Hill. The Federals had arrived two days earlier, and began to shell the city proper, killing several civilians.[12] A savage struggle, sometimes hand-to-hand, developed around the hill, lasting until just after dark. The Federals held the hill while the Confederates retired to a point just south of there. Meanwhile, two miles to the north, Cheatham's troops had broken through the Union lines at the Georgia railroad. In response, twenty artillery pieces were positioned near Sherman's headquarters at Copen Hill, and shelled the Confederates, while Logan's XV Corps regrouped and repulsed the Southern troops.[1]

The Union had suffered about 3,400 casualties, including Maj. Gen. McPherson,[5] to the Confederate's 5,500.[4] This was a devastating loss for the already reduced Confederate army, but they still held the city.

Siege and closure

Sherman settled into a siege of Atlanta, shelling the city and sending raids west and south of the city to cut off the supply lines from Macon, Georgia. Both of Sherman's cavalry raids including McCook's raid and Stoneman's Raid were defeated by Confederate cavalry collectively under General Wheeler. Although the raids partially achieved their objective of cutting railroad tracks and destroying supply wagons, they were soon after repaired and supplies continued to move to the city of Atlanta.[14] [12] Following the failure to break the Confederates' hold on the city, Sherman began to employ a new strategy. He swung his entire army in a broad flanking maneuver to the west.[12] Finally, on August 31, at Jonesborough, Georgia, Sherman's army captured the railroad track from Macon, pushing the Confederates to Lovejoy's Station. With his supply lines fully severed, Hood pulled his troops out of Atlanta the next day, September 1, destroying supply depots as he left to prevent them from falling into Union hands. He also set fire to eighty-one loaded ammunition cars, which led to a conflagration watched by hundreds.[15]

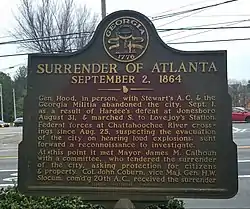

On September 2,[7] Mayor James Calhoun,[16] along with a committee of Union-leaning citizens including William Markham,[15] Jonathan Norcross, and Edward Rawson, met a captain on the staff of Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum, and surrendered the city, asking for "protection to non-combatants and private property".[15] Sherman, who was in Jonesboro at the time of surrender,[15] sent a telegram to Washington on September 3, reading, "Atlanta is ours, and fairly won".[17][18] He then established his headquarters there on September 7, where he stayed for over two months. On November 15, the army departed east toward Savannah, on what became known as "Sherman's March to the Sea".[7]

Aftermath

The fall of Atlanta and the success of the overall Atlanta Campaign were extensively covered by Northern newspapers, and were a boon to Northern morale and to President Lincoln's political standing. The 1864 election was between General George B. McClellan and Abraham Lincoln. McClellan ran a conflicted campaign: McClellan was a Unionist who advocated continuing the war until the defeat of the Confederacy, but the Democratic platform included calls for negotiations with the Confederacy on the subject of a potential truce. The capture of Atlanta and Hood's burning of military facilities as he evacuated showed that a successful conclusion of the war was in sight, weakening support for a truce. Lincoln was reelected by a wide margin, with 212 out of 233 electoral votes.[7]

Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson, who was one of the highest-ranking Union officers killed in action during the Civil War, was mourned and honored by Sherman, who declared in his official report:

His public enemies, even the men who directed the fatal shot, never spoke or wrote of him without expressions of marked respect; those whom he commanded loved him even to idolatry; and I, his associate and commander, fail in words adequate to express my opinion of his great worth. I feel assured that every patriot in America, on hearing this sad news, will feel a sense of personal loss, and the country generally will realize that we have lost, not only an able military leader, but a man who, had he survived, was qualified to heal the national strife which has been raised by designing and ambitious men.[19]

Despite the damage caused by the war, Atlanta recovered from its downfall relatively quickly; as one observer noted as early as November 1865, "A new city is springing up with marvelous rapidity".[20][21] Within a week of the fall of Atlanta however, Sherman had issued all non-military personnel out of Atlanta. Reportedly he remembered the cities of Memphis and Vicksburg which became a burden immediately after victory, so he told the civilians specifically to go north or go south. A truce of sorts was quickly established at a town nearby called Rough And Ready with General Hood, where Union and Confederate prisoners were in small numbers exchanged and civilians wishing to go south could get help to that end.[14]

Legacy

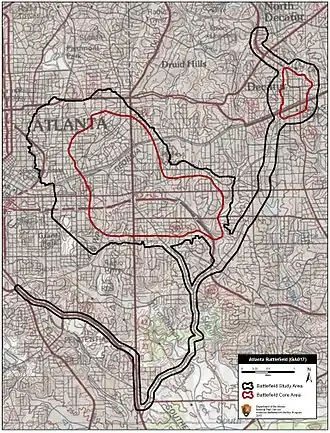

In 1880, Atlanta ranked among the fifty largest cities in the United States.[20] The battlefield is now urban, residential, and commercial land, with many markers memorializing notable events of the battle,[23] including McPherson's place of death. The marker was erected in 1956 by the Georgia Historical Commission.[24] To commemorate the 140th anniversary of the battle, in 2004, two new markers were erected in the Inman Park neighborhood. The Atlanta Cyclorama building, built in 1921 and listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is located in Grant Park and formerly contained a panoramic painting of the battle.[20][25] In 2014, the City of Atlanta sold the Battle of Atlanta Cyclorama to Atlanta History Center.[26] Atlanta History Center constructed new, purpose-built building at their Buckhead Campus to house the art piece. The painting itself underwent an extensive restoration to reverse changes made to the original painting in the 1890s.[27] The Cyclorama and accompanying exhibition (Cyclorama: The Big Picture) opened at Atlanta History Center on February 22, 2019.[28]

One notable establishment destroyed by Union soldiers was the Potter (or Ponder) House, built in 1857, and owned by Ephraim G. Ponder, a holder of 65 slaves before the war. In the battle, it was used by Confederate sharpshooters until Union artillery inflicted heavy damage. It was never rebuilt. One of Ponder's slaves, Festus Flipper, was the father of Henry Ossian Flipper, who later became the first African American cadet to graduate from the United States Military Academy at West Point.[29]

See also

Notes

- "Battle Summary: Atlanta, GA". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 19, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- Livermore (p. 122-123, 142) cites values of Union troops as 34,863 present for duty and 30,477 effective, and Confederate troops as 40,438 present for duty and 36,934 effective. Bodart (1908) (p. 538) gives the strength of the Union forces as circa 70,000 and the Confederate forces as circa 40,000.

- Kennedy 1998, p. 340.

- Bonds 2009, p. 172.

- Ecelbarger 2010, p. 233.

- Ecelbarger 2010, p. 237.

- Boyer et al. 2007, p. 457.

- Symonds 1994, p. 326.

- Bonds 2009, p. 106.

- Ecelbarger 2010, p. 115.

- Ecelbarger 2010, p. 236.

- Garrett 1987.

- "Civil War Medal of Honor Recipients - (M-Z)". U.S. Army Center of Military History. Archived from the original on December 31, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- Matthews, Byron H. (1976). The McCook-Stoneman Raid. Brannon Publishing.

- Garrett 1987, p. 633–638.

- "Surrender of Atlanta, September 2, 1864". Marietta Street Artery Association. Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved January 18, 2011.

- Cox 1994, p. xv.

- "Today in History: September 1". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on January 15, 2011. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- Reid 1868, p. 587-588.

- "Industrial Atlanta". National Park Service. Retrieved February 21, 2011.

- Cooper, Jr., William J.; Terrill, Thomas E. (2008). The American South: A History, Volume 2. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 468.

- "Underground Atlanta Walking Tour". Archived from the original on February 22, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- "Atlanta Markers - The Historical Marker Database". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- "Death of McPherson Marker". The Historical Marker Database. Retrieved February 6, 2011.

- "Grant Park Historic District". National Park Service. Retrieved December 28, 2010.

- do, Things to. "Atlanta's Cyclorama: A timeline and history of the Battle of Atlanta painting". ajc. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- McFadden, Jack Hitt,Joshua Rashaad. "Atlanta's Famed Cyclorama Mural Will Tell the Truth About the Civil War Once Again". Smithsonian. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- Bo Emerson, The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. "Restored Cyclorama opens". ajc. Retrieved August 1, 2019.

- "THE POTTER HOUSE ATLANTA Photo from nature By G. N. Barnard". Digital Library of Georgia. Retrieved February 26, 2011.

References

- Bonds, Russell S. (2009). War Like the Thunderbolt: The Battle and Burning of Atlanta. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59416-100-1.

- Boyer, Paul; Clark, Jr., Clifford; Kett, Joseph; Salisbury, Neal; Sitkoff, Harvard; Woloch, Nancy (2007). The Enduring Vision (6th AP ed.). Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-80163-3.

- Cox, Jacob D. (1994). Sherman's Battle for Atlanta. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80588-2.

- Ecelbarger, Gary (2010). The Day Dixie Died: The Battle of Atlanta. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-312-56399-8.

- Garrett, Franklin (1987). Atlanta and Environs: A Chronicle of Its People and Events, Volume 1. University of Georgia Press. OCLC 191446.

- Golden, Randy. "The Battle of Atlanta". About North Georgia. Archived from the original on December 19, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- Hood, John Bell. Advance and Retreat: Personal Experiences in the United States and Confederate States Armies. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-8032-7285-9. First published 1880 for the Hood Orphan Memorial Fund by G.T. Beauregard.

- Hood, Stephen M. John Bell Hood: The Rise, Fall, and Resurrection of a Confederate General. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2013. ISBN 978-1-61121-140-5.

- Kennedy, Frances H. (1998). The Civil War Battlefield Guide (2nd ed.). Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. ISBN 0-395-74012-6.

- Reid, Whitelaw (1868). Ohio in the War: Her Statesmen, Her Generals, and Soldiers. Moore, Wilstach & Baldwin.

- Swan, James B. (2009). Chicago's Irish Legion: the 90th Illinois Volunteers in the Civil War. Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 978-0809328901. OCLC 232327691.

- Symonds, Craig (1994). Joseph E. Johnston: A Civil War Biography. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-31130-3.

- Livermore, Thomas Leonard (1900). Numbers and Losses in the Civil War in America, 1861-1865. Houghton, Mifflin and company.

- Bodart, Gaston (1908). Militär-historisches kreigs-lexikon, (1618-1905). Stern.

Memoirs and primary sources

- Sherman, William T., Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman, 2nd ed., D. Appleton & Co., 1913 (1889). Reprinted by the Library of America, 1990, ISBN 978-0-940450-65-3.

- U.S. War Department, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1880–1901.

Further reading

- Cozzens, Peter (2002). Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-02404-7.

- Foote, Shelby (1974). The Civil War, A Narrative: Red River to Appomattox. Random House. ISBN 0-394-74913-8.

- McDonough, James Lee (June 14, 2016). William Tecumseh Sherman, In the Service of my Country, A Life. W. W. Norton & Company, New York. ISBN 978-0-3932-4212-6.

- Dodge, Grenville Mellen (1910). The Battle of Atlanta and Other Campaigns, Addresses, Etc. The Monarch Printing Company.

- Secrist, Philip L. (2006). Sherman's 1864 Trail of Battle to Atlanta. Mercer University Press. ISBN 978-0-86554-745-2.

- Ecelbarger, Gary (2010). The Day Dixie Died – The Battle of Atlanta. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-0-312-56399-8.

External links

- Russell Bonds discusses War Like the Thunderbolt: The Battle and Burning of Atlanta at the Pritzker Military Museum & Library

.svg.png.webp)