Fulton County, Georgia

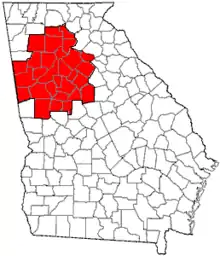

Fulton County is located in the north-central portion of the U.S. state of Georgia. As of 2019 estimates, the population was 1,063,937, making it the state's most-populous county and its only one with over 1 million inhabitants.[1] Its county seat is Atlanta,[2] the state capital. Approximately 90% of the City of Atlanta is within Fulton County; the other 10% lies within DeKalb County.

Fulton County | |

|---|---|

| County of Fulton | |

Atlanta's Fulton County Courthouse in 2011 | |

Location within the U.S. state of Georgia | |

Georgia's location within the U.S. | |

| Coordinates: 33°47′N 84°28′W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| Founded | December 20, 1853 |

| Named for | Hamilton Fulton |

| Seat | Atlanta |

| Largest city | Atlanta |

| Area | |

| • Total | 534 sq mi (1,380 km2) |

| • Land | 527 sq mi (1,360 km2) |

| • Water | 7.7 sq mi (20 km2) 1.4%% |

| Population | |

| • Estimate (2019) | 1,063,937[1] |

| • Density | 1,967/sq mi (759/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| Congressional districts | 5th, 6th, 11th, 13th |

| Website | www |

Fulton County is part of the Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

Fulton County was created in 1853 from the western half of DeKalb County. It was named in honor of Hamilton Fulton, a railroad official who acted as surveyor for the Western and Atlantic Railroad and also as chief engineer of the state. After surveying the area that is now Fulton County, Fulton convinced state officials that a railroad, rather than a canal, should be constructed to connect Milledgeville, then the state capital, to Chattanooga, Tennessee. Building the railroad was a precursor of Fulton County's prominence as a major transportation center.[3][4] Organized as settlement increased in the Piedmont section of upland Georgia, Fulton County grew rapidly after the American Civil War as Atlanta was rebuilt, becoming a center of railroad shipping, industry and business.

After the war, there was considerable violence against freedmen in the county. During the post-Reconstruction period, violence and the number of lynchings of blacks increased in the late 19th century, as whites exercised terrorism to re-establish and maintain white supremacy. Whites lynched 35 African Americans here from 1877 to 1950; According to the Georgia Lynching Project, 24 were killed in 1906. This was the highest total in the state.[5] With a total of 589, Georgia was second to Mississippi in its total number of lynchings in this period.[6]

In addition to individual lynchings, during the Atlanta Race Riot of 1906, whites killed at least 25 African Americans; the number may have been considerably higher. Two white persons died during the riot; one a woman who died of a heart attack. The violence affected black residential and business development in the city afterward. The Georgia legislature effectively completed disenfranchisement of African Americans in 1908, with constitutional amendments that raised barriers to voter registration and voting, excluding them from the political system.

At the beginning of 1932, as an austerity measure to save money during the Great Depression, Fulton County annexed Milton County to the north and Campbell County to the southwest, to centralize administration. That resulted in the current long shape of the county along 80 miles (130 km) of the Chattahoochee River. On May 9 of that year, neighboring Cobb County ceded the city of Roswell and lands lying east of Willeo Creek to Fulton County so that it would be more contiguous with the lands ceded from Milton County.

In the second half of the 20th century, Atlanta and Fulton county became the location of numerous national and international headquarters for leading companies, attracting highly skilled employees from around the country. This led to the city and county becoming more cosmopolitan and diverse.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 534 square miles (1,380 km2), of which 527 square miles (1,360 km2) is land and 7.7 square miles (20 km2) (1.4%) is water.[7] The county is located in the Piedmont region of the state in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains to the north. The shape of the county resembles a sword with its handle at the northeastern part, and the tip at the southwestern portion.

Going from north to south, the northernmost portion of Fulton County, encompassing Milton and northern Alpharetta, is located in the Etowah River sub-basin of the ACT River Basin (Coosa-Tallapoosa River Basin). The rest of north and central Fulton, to downtown Atlanta, is located in the Upper Chattahoochee River sub-basin of the ACF River Basin (Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint River Basin). The bulk of south Fulton County, from Atlanta to Palmetto, is located in the Middle Chattahoochee River-Lake Harding sub-basin of the larger ACF River Basin, with just the eastern edges of south Fulton, from Palmetto northeast through Union Hill to Hapeville, in the Upper Flint River sub-basin of the same larger ACF River Basin.[8]

National protected areas

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 14,427 | — | |

| 1870 | 33,446 | 131.8% | |

| 1880 | 49,137 | 46.9% | |

| 1890 | 84,655 | 72.3% | |

| 1900 | 117,363 | 38.6% | |

| 1910 | 177,733 | 51.4% | |

| 1920 | 232,606 | 30.9% | |

| 1930 | 318,587 | 37.0% | |

| 1940 | 392,886 | 23.3% | |

| 1950 | 473,572 | 20.5% | |

| 1960 | 556,326 | 17.5% | |

| 1970 | 607,592 | 9.2% | |

| 1980 | 589,904 | −2.9% | |

| 1990 | 648,951 | 10.0% | |

| 2000 | 816,006 | 25.7% | |

| 2010 | 920,581 | 12.8% | |

| 2019 (est.) | 1,063,937 | [9] | 15.6% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[10] 1790-1960[11] 1900-1990[12] 1990-2000[13] 2010-2014[14] | |||

2019 ACS Estimates

| Population[15] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Group | Estimate | Percent |

| Total Population | 1,063,937 | |

| Population by Sex[15] | ||

| Group | Estimate | Percent |

| Male | 514,901 | 48.4% |

| Female | 549,036 | 51.6% |

| Sex ratio (males per 100 females) | 93.8 | |

| Population by Age[15] | ||

| Group | Estimate | Percent |

| Under 5 years | 61,084 | 5.7% |

| 5 to 9 years | 60,180 | 5.7% |

| 10 to 14 years | 67,278 | 6.3% |

| 15 to 19 years | 72,060 | 6.8% |

| 20 to 24 years | 74,294 | 7.0% |

| 25 to 29 years | 96,369 | 9.1% |

| 30 to 34 years | 87,402 | 8.2% |

| 35 to 39 years | 79,641 | 7.5% |

| 40 to 44 years | 70,973 | 6.7% |

| 45 to 49 years | 76,114 | 7.2% |

| 50 to 54 years | 69,491 | 6.5% |

| 55 to 59 years | 67,289 | 6.3% |

| 60 to 64 years | 54,006 | 5.1% |

| 65 to 69 years | 46,168 | 4.3% |

| 70 to 74 years | 32,696 | 3.1% |

| 75 to 79 years | 20,164 | 1.9% |

| 80 to 84 years | 13,160 | 1.2% |

| 85 years and over | 15,568 | 1.5% |

| Median age (years) | 35.9 | |

| Population by Race and Ethnicity[16] | ||

| Group | Estimate | Percent |

| Black or African American | 472,625 | 44.4% |

| White | 469,465 | 44.1% |

| --- White, not Hispanic or Latino | 418,482 | 39.3% |

| Asian | 76,786 | 7.2% |

| --- Asian Indian | 43,438 | 4.1% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 76,773 | 7.2% |

| --- Mexican | 28,037 | 2.6% |

| Two or more races | 25,072 | 2.4% |

| Some other race | 17,248 | 1.6% |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 2,068 | 0.2% |

| Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander | 673 | 0.1% |

| Population by Nativity and Citizenship Status[17] | ||

| Group | Estimate | Percent |

| Native (born in the United States) | 927,795 | 87.2% |

| --- Born in Georgia | 472,774 | 44.4% |

| --- Born in other U.S. state | 437,881 | 41.2% |

| ------ Southern state | 199,155 | 18.7% |

| ------ Northeastern state | 105,811 | 9.9% |

| ------ Midwestern state | 92,026 | 8.6% |

| ------ Western state | 40,889 | 3.8% |

| --- Native born outside U.S. states | 17,140 | 1.6% |

| Foreign Born | 136,142 | 12.8% |

| --- Not a U.S. citizen | 69,083 | 6.5% |

| --- Naturalized U.S. citizen | 67,059 | 6.3% |

2010 Census

As of the 2010 United States Census, there were 920,581 people, 376,377 households, and 209,215 families residing in the county.[18] The population density was 1,748.0 inhabitants per square mile (674.9/km2). There were 437,105 housing units at an average density of 830.0 per square mile (320.5/km2).[19] The racial makeup of the county was 46.4% white, 44.3% black or African American, 6.9% Asian, 0.2% American Indian, 3.4% from other races, and 2.2% from two or more races. Those of Hispanic or Latino origin made up 7.5% of the population.[18] In terms of ancestry, 7.7% were English, 7.2% were German, 6.3% were Irish, and 5.4% were "American".[20]

Of the 376,377 households, 30.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 35.7% were married couples living together, 15.7% had a female householder with no husband present, 44.4% were non-families, and 35.4% of all households were made up of individuals. The average household size was 2.36 and the average family size was 3.15. The median age was 34.2 years.[18]

The median income for a household in the county was $56,709 and the median income for a family was $75,579. Males had a median income of $56,439 versus $42,697 for females. The per capita income for the county was $37,211. About 12.0% of families and 15.3% of the population were below the poverty line, including 22.0% of those under age 18 and 12.0% of those age 65 or over.[21]

Economy

Companies headquartered in Fulton County include AFC Enterprises (Popeyes Chicken/Cinnabon), AT&T Mobility, Chick-fil-A, Children's Healthcare of Atlanta, Church's Chicken, The Coca-Cola Company, Cox Enterprises, Delta Air Lines, Earthlink, Equifax, First Data, Georgia-Pacific, Global Payments, Inc., InterContinental Hotels Group, IBM Internet Security Systems, Mirant Corp., Newell Rubbermaid, Northside Hospital, Piedmont Healthcare, Porsche Cars North America, Saint Joseph's Hospital, Southern Company, Spectrum Brands, SunTrust Banks, United Parcel Service, and Wendy's/Arby's Group are based in various cities throughout Fulton County.

MaggieMoo's and Marble Slab Creamery had their headquarters in an unincorporated area in the county, however, now those companies are located in neighboring Gwinnett County in Norcross.[22][23]

Government

Fulton County is governed by a seven-member board of commissioners, whose members are elected from single-member districts. They serve concurrent four-year terms. The county has a county manager system of government, in which day-to-day operation of the county is handled by a manager appointed by the board. The chairman of the Board of Commissioners is elected at-large for the county-wide position. The vice chairman is elected by peers on a yearly basis.

| Board of Commissioners | ||

|---|---|---|

| District | Commissioner | Party |

| District 7 (At-Large) | Robb Pitts (Chairman) | Democratic |

| District 1 | Liz Hausmann | Republican |

| District 2 | Bob Ellis | Republican |

| District 3 | Lee Morris | Republican |

| District 4 | Natalie Hall | Democratic |

| District 5 | Marvin S. Arrington, Jr. | Democratic |

| District 6 | Joe Carn | Democratic |

| Board of Commissioners Appointees | |

|---|---|

| Position held | Name |

| County Manager | Dick Anderson |

| Clerk to the Commission | Tonya Grier (interim) |

| County Attorney | Patrise Perkins-Hooker |

| Chief Financial Officer | Sharon Whitmore |

| Chief Operating Officer | Anna Roach |

Politics

Atlanta is the largest city in Fulton County, occupying the county's narrow center section and thus geographically dividing the county's northern and southern portions. Atlanta's last major annexation in 1952 brought over 118 square miles (310 km2) into the city, including the affluent suburb of Buckhead. The movement to create a city of Sandy Springs, launched in the early 1970s and reaching fruition in 2005, was largely an effort to prevent additional annexations by the city of Atlanta, and later to wrest local control from the county commission.

Fulton County is one of the most reliably Democratic counties in the entire nation. It has voted Democratic in every presidential election since 1876, except that of 1928 and again in 1972, when George McGovern could not win a single county in Georgia. The demographic character of the Democratic Party has changed; as conservative Caucasians, previously its chief members in the South, have mostly shifted to the Republican Party. In Fulton County, Democrats are composed primarily of liberal urbanites of various ethnicities, and a growing contingent of suburban voters. Except for a small sliver of Buckhead, the entire county is represented by Democrats in the U.S. House, with David Scott representing the southern suburbs, Lucy McBath representing most of the northern suburbs, which had historically been reliably Republican, and John Lewis representing the core of Atlanta until his death on July 17, 2020.[24] Lewis' seat is currently represented by Nikema Williams.

| Year | Republican | Democratic | Third parties |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 26.2% 137,247 | 72.5% 380,212 | 1.2% 6,320 |

| 2016 | 26.9% 117,783 | 67.7% 297,051 | 5.5% 23,917 |

| 2012 | 34.4% 137,124 | 64.1% 255,470 | 1.4% 5,752 |

| 2008 | 32.1% 130,136 | 67.1% 272,000 | 0.9% 3,489 |

| 2004 | 39.9% 134,372 | 59.2% 199,436 | 0.9% 2,933 |

| 2000 | 39.8% 104,870 | 57.8% 152,039 | 2.4% 6,303 |

| 1996 | 36.9% 89,809 | 58.9% 143,306 | 4.1% 10,053 |

| 1992 | 33.2% 85,451 | 57.3% 147,459 | 9.5% 24,499 |

| 1988 | 42.8% 91,785 | 56.3% 120,752 | 1.0% 2,152 |

| 1984 | 43.1% 95,149 | 56.9% 125,567 | |

| 1980 | 33.7% 64,909 | 61.6% 118,748 | 4.7% 9,066 |

| 1976 | 32.2% 61,552 | 67.8% 129,849 | |

| 1972 | 56.4% 96,256 | 43.6% 74,329 | |

| 1968 | 35.8% 64,153 | 43.5% 77,920 | 20.7% 36,995 |

| 1964 | 43.9% 73,205 | 56.1% 93,540 | 0.0% 11 |

| 1960 | 49.2% 53,940 | 50.9% 55,803 | |

| 1956 | 42.2% 37,326 | 57.8% 51,098 | |

| 1952 | 40.2% 35,197 | 59.9% 52,459 | |

| 1948 | 29.3% 14,976 | 57.4% 29,318 | 13.2% 6,760 |

| 1944 | 17.1% 7,687 | 82.9% 37,161 | |

| 1940 | 16.1% 6,033 | 83.6% 31,311 | 0.3% 122 |

| 1936 | 11.5% 3,552 | 88.2% 27,183 | 0.3% 94 |

| 1932 | 9.2% 2,063 | 89.7% 20,137 | 1.1% 253 |

| 1928 | 51.4% 9,368 | 48.6% 8,872 | |

| 1924 | 25.6% 3,229 | 62.0% 7,830 | 12.5% 1,579 |

| 1920 | 33.5% 3,336 | 66.5% 6,635 | |

| 1916 | 9.2% 1,040 | 79.2% 8,945 | 11.6% 1,311 |

| 1912 | 17.8% 1,688 | 76.9% 7,313 | 5.3% 507 |

| 1908 | 35.7% 2,906 | 58.8% 4,790 | 5.3% 438 |

| 1904 | 22.5% 1,766 | 73.6% 5,781 | 3.8% 301 |

| 1900 | 24.5% 1,676 | 74.3% 5,075 | 1.1% 75 |

| 1896 | 38.0% 3,005 | 57.0% 4,504 | 4.9% 391 |

| 1892 | 21.8% 1,364 | 74.6% 4,663 | 3.5% 223 |

| 1888 | 42.0% 2,164 | 53.4% 2,750 | 4.5% 233 |

| 1884 | 32.3% 925 | 67.7% 1,939 | |

| 1880 | 42.2% 2,229 | 57.7% 3,045 |

Taxation

Geographically remote from each other, the northern and southern sections of the county have grown increasingly at odds over issues related to taxes and distribution of services. Residents of the affluent areas of North Fulton have increasingly complained that the Fulton County Board of Commissioners has ignored their needs, taking taxes collected in North Fulton, and spending them on programs and services in less wealthy South Fulton. In 2005, responding to pressure from North Fulton, the Georgia General Assembly directed Fulton County, alone among all the counties in the state, to limit the expenditure of funds to the geographic region of the county where they were collected. The Fulton County Commission contested this law, known as the "Shafer Amendment" after Sen. David Shafer (Republican from Duluth), in a lawsuit that went to the Georgia Supreme Court. On June 19, 2006, the Court upheld the law, ruling that the Shafer Amendment was constitutional.

The creation of the city of Sandy Springs stimulated the founding of two additional cities, resulting in no unincorporated areas remaining in north Fulton. In a domino effect, the residents of southwest Fulton voted in referenda to create additional cities. In 2007, one of these two referenda passed and the other was defeated, but later passed in 2016.

Municipalization

Since the 1970s, residents of Sandy Springs had waged a long-running battle to incorporate their community as a city, which would make it independent of county council control. They were repeatedly blocked in the state legislature by Atlanta Democrats, but when control of state government switched to suburban Republicans after the 2002 and 2004 elections, the movement to charter the city picked up steam.

The General Assembly approved creation of the city in 2005, and for this case, it suspended an existing state law that prohibited new cities (the only type of municipality in the state) from being within three miles (4.8 km) of an existing one. The citizens of Sandy Springs voted 94% in favor of ratifying the city charter in a referendum held on June 21, 2005. The new city was officially incorporated later that year at midnight on December 1.

Creation of Sandy Springs was a catalyst for municipalization of the entire county, in which local groups would attempt to incorporate every area into a city. Such a result would essentially eliminate the county's home rule powers (granted statewide by a constitutional amendment to the Georgia State Constitution in the 1960s) to act as a municipality in unincorporated areas, and return it to being entirely the local extension of state government.

In 2006, the General Assembly approved creation of two new cities, Milton and Johns Creek, which completed municipalization of North Fulton. The charters of these two new cities were ratified overwhelmingly in a referendum held July 18, 2006.

Voters in the Chattahoochee Hills community of southwest Fulton (west of Cascade-Palmetto Highway) voted overwhelmingly to incorporate in June 2007. The city became incorporated on December 1, 2007.

The General Assembly approved a proposal to form a new city called South Fulton. Its proposed boundaries were to include those areas still unincorporated on July 1, 2007. As a direct result of possibly being permanently landlocked, many of the existing cities proposed annexations, while some communities drew-up incorporation plans.[26]

Voters in the area defined as the proposed city of South Fulton overwhelmingly rejected cityhood in September 2007. It was the only remaining unincorporated section of the county until the residents voted in November 2016 to incorporate as the city of South Fulton, Georgia. Prior to that vote North Fulton, which is overwhelmingly Republican, and members of the state legislature, had discussed forcing South Fulton residents to incorporate as a city in order to force Fulton County out of the municipal services business.

Secession

Some residents of suburban north Fulton have advocated that they be allowed to secede and re-form Milton County, after the county that was absorbed into Fulton County in 1932 during the Great Depression. Fulton County, in comparison to the state's other counties, is physically large. Its population is greater than that of each of the six smallest U.S. states.

The demographic make-up of Fulton County has changed considerably in recent decades. The northern portion of the county, a suburban area, is among the most affluent areas in the nation and is majority white. It was formerly a Republican stronghold, but has seen a shift toward the Democratic Party since the early 2010s. In 2018, Lucy McBath won the 6th Congressional District, the majority of which is in North Fulton. The central and southern portion of the county, which includes the city of Atlanta and its core satellite cities to the south, is overwhelmingly Democratic and majority black. It contains some of the poorest sections in the metropolitan area, but also has wealthy sections, particularly in Midtown Atlanta, many east Atlanta neighborhoods, and in the suburban neighborhoods along Cascade Road beyond I-285. Cascade Heights and Sandtown, located in the southwest region of Fulton County, are predominantly affluent African American in population.[27]

The chief opponents to the proposed division of the county comes from the residents of south Fulton County, who say that the proposed separation is racially motivated. State Senator Vincent Fort, an Atlanta Democrat and a member of the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus, very strongly opposes the plan to split the county. "If it gets to the floor, there will be blood on the walls", Fort stated. "As much as you would like to think it's not racial, it's difficult to draw any other conclusion", he later added.[28]

In 2006 a political firestorm broke out in Atlanta when State Senator Sam Zamarripa (Democrat from Atlanta) suggested that the cities in North Fulton be allowed to secede and form Milton County in exchange for Atlanta and Fulton County consolidating their governments into a new "Atlanta County". South Fulton residents were strongly opposed to Fulton County's possible future division.

Taxes

Fulton County has a 7% total sales tax, including 4% state, 1% SPLOST, 1% homestead exemption, and 1% MARTA. Sales taxes apply through the entire county and its cities, except for Atlanta's additional 1% Municipal Option Sales Tax to fund capital improvements to its combined wastewater sewer systems (laying new pipes to separate storm sewers from sanitary sewers), and to its drinking water system.[29] Fulton County has lowered its general fund millage rate by 26% over an eight-year period.

In early 2017, the state's first (and so far only) fractional-percent sales taxes took effect in Fulton. Atlanta added an additional 0.5% for MARTA and 0.4% TSPLOST for other transportation projects, while anti-transit Republican legislators from north Fulton blocked a countywide referendum on improving and extending MARTA, and instead allowed only a vote on a 0.75% TSPLOST for more roads in the areas outside Atlanta. This puts the total sales tax at 8.9% in Atlanta and 7.75% in the rest of the county, with 4% less on groceries.

Services

Fulton County's budget of $1.2 billion funds an array of resident services. With 34 branches, the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System is one of the largest library systems in Georgia. Human services programs include one of the strongest senior center networks in metro Atlanta, including four multi-purpose senior facilities. The county also provides funding to nonprofits with FRESH and Human Services grants.

Transportation

Almost every major highway, and every major Interstate highway, in metro Atlanta passes through Fulton County. Outside Atlanta proper, Georgia 400 is the major highway through north Fulton, and Interstate 85 to the southwest.

Interstate highways

U.S. highways

State routes

State Route 3

State Route 3 State Route 3 Connector

State Route 3 Connector State Route 6

State Route 6 State Route 8

State Route 8 State Route 9

State Route 9 State Route 10

State Route 10 State Route 13

State Route 13 State Route 14

State Route 14 State Route 14 Alternate

State Route 14 Alternate State Route 14 Connector

State Route 14 Connector State Route 42

State Route 42 State Route 42 Connector

State Route 42 Connector State Route 42 Spur

State Route 42 Spur State Route 54

State Route 54 State Route 54 Connector

State Route 54 Connector State Route 70

State Route 70 State Route 74

State Route 74 State Route 92

State Route 92 State Route 120

State Route 120 State Route 138

State Route 138 State Route 139

State Route 139 State Route 140

State Route 140 State Route 141

State Route 141 State Route 154

State Route 154 State Route 154 Connector

State Route 154 Connector State Route 166

State Route 166 State Route 236

State Route 236 State Route 237

State Route 237 State Route 279

State Route 279 State Route 280

State Route 280 State Route 372

State Route 372 State Route 400

State Route 400 State Route 401 (unsigned designation for I-75)

State Route 401 (unsigned designation for I-75) State Route 402 (unsigned designation for I-20)

State Route 402 (unsigned designation for I-20) State Route 403 (unsigned designation for I-85)

State Route 403 (unsigned designation for I-85) State Route 407 (unsigned designation for I-285)

State Route 407 (unsigned designation for I-285)

Secondary highways

- Abernathy Road

- East Wesley Road

- Freedom Parkway (Georgia 10)

- Glenridge Drive

- Hammond Drive

- Johnson Ferry Road

- Lindbergh Drive (Georgia 236)

- Memorial Drive (Georgia 154)

- Moreland Avenue (U.S. 23/Georgia 42)

- Mount Vernon Highway

- Peachtree Road (Georgia 141)

- Peachtree-Dunwoody Road

- Piedmont Road (Georgia 237)

- Ponce de Leon Avenue (U.S. 23/29/78/278/Georgia 8/10)

- Powers Ferry Road

- Roswell Road (U.S. 19/Georgia 9)

- Windsor Parkway

Mass transit

MARTA serves most of the county, and along with Clayton and Dekalb County, Fulton pays a 1% sales tax to fund it. MARTA train service in Fulton is currently limited to the cities of Atlanta, Sandy Springs, East Point, and College Park, as well as the airport. Bus service covers most of the remainder, except the rural areas in the far southwest. North Fulton residents have been asking for service, to extend the North Line ten miles (16 km) up the Georgia 400 corridor, from Perimeter Center to the fellow edge city of Alpharetta. However, as the only major transit system in the country that its state government will not fund, there is no money to expand the system. Sales taxes now go entirely to operating, maintaining, and refurbishing the system. Xpress GA/ RTA provides commuter bus service from the outer suburbs of Fulton County, the city of Sandy Springs to Midtown and Downtown Atlanta.

Recreational trails

- BeltLine (under construction)[30]

- Big Creek Greenway (under construction)[31]

- PATH400 (under construction)[32]

- Peachtree Creek Greenway (under construction)[33]

Airports

Hartsfield-Jackson Atlanta International Airport straddles the border with Clayton County to the south and is the busiest airport in the world. The Fulton County Airport, often called Charlie Brown Field after politician Charles M. Brown, is located just west-southwest of Atlanta's city limit. It is run by the county as a municipal or general aviation airport, serving business jets and private aircraft.

Education

All portions of Fulton County outside of the city limits of Atlanta are served by the Fulton County School System.

All portions within Atlanta are served by Atlanta Public Schools.

History

The Atlanta-Fulton County Library system began in 1902 as the Carnegie Library of Atlanta, one of the first public libraries in the United States. In 1935, the city of Atlanta and the Fulton County Board of Commissioners signed a contract under which library service was extended to all of Fulton County. Then in 1982, Georgia voters passed a constitutional Amendment authorizing the transfer of responsibility for the Library system from the city of Atlanta to the county. On July 1, 1983, the transfer finally became official, and the system was renamed the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System.

Under the leadership of Ella Gaines Yates, who was the first African American director of the Library System, a new Central library was opened to the public in May 1988. The building was designed by Marcel Breuer, a participant in the innovative Bauhaus movement, working side by side with his associate Hamilton Smith. The Central Library was dedicated on May 25, 1980 and Breuer would die a year later on July, 1981 at the age of 81.

In 2002 after a hundred years of library service to the public, a major renovation of the Central Library was completed.

Mission

Under the current director of the Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System, Dr. Gabriel Morley who was appointed on April 20, 2017, the libraries serve as a cultural and intellectual center that enriches the community and empowers all residents with essential tools for lifelong learning. The Atlanta-Fulton Public Library System serves the citizens of Fulton County and the City of Atlanta. It is the largest System in the state with 34 different library branches and a collection of more than 2.5 million items. it offers new and creative programs, services and virtual resources customized to meet the needs of each branch's community. A variety of classes are offered to children, teens, and adults. Also available to the customers are the opportunities to visit exhibitions, listen to author's discuss their work, checkout videos, DVD's and CD's. There are also book club discussions that can be attended, people can get homework help, listen to music and see live performances.

In 2016, patrons borrowed over 4.2 million items, made 4 million visits to the libraries and its website had over 4 million hits.

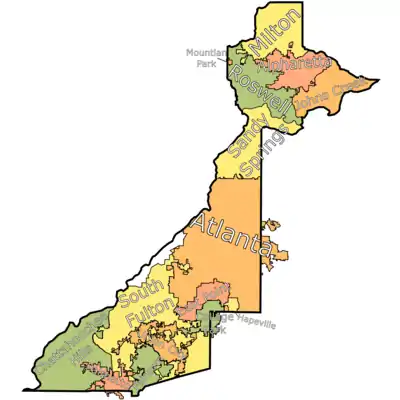

Communities

There are 15 cities within Fulton County. Four cities include land outside of the county (Atlanta, College Park, Palmetto, and Mountain Park) but still have their center of government and the majority of their land within Fulton County. After the formation of South Fulton in 2017, the only unincorporated part of the county is Fulton Industrial Boulevard, from roughly Fulton Brown Airport (Brown's Field) down to Fairburn Rd. (concurrent with GA-158 and GA-166)[34] This led to Fulton County becoming the first county in Georgia to suspend all city services.[35]

Cities

Adjacent counties

- Cherokee County – northwest

- Forsyth County – northeast

- Gwinnett County – east

- DeKalb County – east

- Clayton County – south

- Fayette County – south

- Coweta County – southwest

- Carroll County – west

- Douglas County – west

- Cobb County – west

Former unincorporated communities

See also

References

- "2019 County Metro Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- Fulton County, The New Georgia Encyclopedia

- Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 133.

- Lynching in America/ Supplement: Lynchings by County, 3rd Edition, 2015, p. 4

- AJC Staff, "Hundreds more were lynched in the South than previously known: report", Atlanta Journal-Constitution, 14 June 2017; accessed 26 March 2018

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission Interactive Mapping Experience". Georgia Soil and Water Conservation Commission. Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- "2019 County Metro Population Estimates". Retrieved March 26, 2020.

- "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Retrieved June 22, 2014.

- "2019 ACS Age and Sex 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- "2019 ACS Demographic and Housing 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- "2019 ACS Place of Birth by Nativity and Citizenship Status 1-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved September 22, 2020.

- "DP-1 Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 Demographic Profile Data". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- "Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density: 2010 - County". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- "DP02 SELECTED SOCIAL CHARACTERISTICS IN THE UNITED STATES – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- "DP03 SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS – 2006-2010 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved December 29, 2015.

- "Contact Us Archived 2010-03-10 at the Wayback Machine." MaggieMoo's. Retrieved on February 26, 2010.

- "Contact Us Archived 2010-02-28 at the Wayback Machine." Marble Slab Creamery. Retrieved on February 26, 2010.

- https://www.nbcboston.com/news/national-international/rep-john-lewis-dies-at-80/2161514/

- Leip, David. "Dave Leip's Atlas of U.S. Presidential Elections". uselectionatlas.org.

- Dewan, Shaila (July 13, 2006). "In Georgia County, Divisions of North and South Play Out in Drives to Form New Cities". The New York Times.

- Census tracts 78.05, 103.01, 103.03 and 103.04

- "Plan to split county hints at racial divide". Retrieved March 19, 2008.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on February 2, 2007. Retrieved February 12, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "ARC allocations could provide for bus transit expansion, funding for Beltline extensions".

- "Alpharetta OKs design to close Big Creek Greenway gap".

- "Roswell backs trail along Ga. 400".

- "Peachtree Creek Greenway work could begin early next year". August 21, 2017.

- "Printable Maps". Fulton County. https://www.fultoncountyga.gov/-/media/Departments/IT_GIS/Printable-Maps/CityLimits_35X44.ashx. External link in

|publisher=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help) - Kass, Arielle. "Fulton County first in Georgia to relinquish city services". Atlanta Journal Constitution. Cox Enterprises. Retrieved April 28, 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fulton County, Georgia. |

.JPG.webp)