Mon language

The Mon language (/ˈmoʊn/,[2] Mon: ဘာသာ မန်; Burmese: မွန်ဘာသာ, Thai: ภาษามอญ, formerly known as Peguan and Talaing) is an Austroasiatic language spoken by the Mon people. Mon, like the related Khmer language, but unlike most languages in mainland Southeast Asia, is not tonal. The Mon language is a recognised indigenous language in Myanmar as well as a recognised indigenous language of Thailand.[3]

| Mon | |

|---|---|

| ဘာသာ မန် | |

| |

| Pronunciation | [pʰesa mɑn] |

| Native to | Myanmar |

| Region | Lower Myanmar |

| Ethnicity | Mon |

Native speakers | 800,000 - 1 million (2007)[1] |

| Mon-Burmese script | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | Either:mnw – Modern Monomx – Old Mon |

omx Old Mon | |

| Glottolog | monn1252 Modern Monoldm1242 Old Mon |

Mon was classified as a "vulnerable" language in UNESCO's 2010 Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger.[4] The Mon language has faced assimilative pressures in both Myanmar and Thailand, where many individuals of Mon descent are now monolingual in Burmese or Thai respectively. In 2007, Mon speakers were estimated to number between 800,000 and 1 million.[5] In Myanmar, the majority of Mon speakers live in Southern Myanmar, especially Mon State, followed by Tanintharyi Region and Kayin State.[6]

History

Mon is an important language in Burmese history. Until the 12th century, it was the lingua franca of the Irrawaddy valley—not only in the Mon kingdoms of the lower Irrawaddy but also of the upriver Pagan Kingdom of the Bamar people. Mon, especially written Mon, continued to be a prestige language even after the fall of the Mon kingdom of Thaton to Pagan in 1057. King Kyansittha of Pagan (r. 1084–1113) admired Mon culture and the Mon language was patronized.

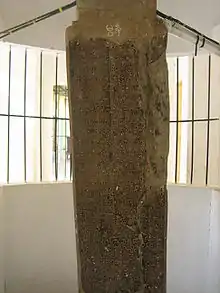

Kyansittha left many inscriptions in Mon. During this period, the Myazedi inscription, which contains identical inscriptions of a story in Pali, Pyu, Mon and Burmese on the four sides, was carved.[7] However, after Kyansittha's death, usage of the Mon language declined among the Bamar and the Burmese language began to replace Mon and Pyu as a lingua franca.[7]

Mon inscriptions from Dvaravati's ruins also litter Thailand. However it is not clear if the inhabitants were Mon, a mix of Mon and Malay or Khmer. Later inscriptions and kingdoms like Lavo were subservient to the Khmer Empire.

After the fall of Pagan, Mon again became the lingua franca of the Hanthawaddy Kingdom (1287–1539) in present-day Lower Myanmar, which remained a predominantly Mon-speaking region until the 1800s, by which point, the Burmese language had expanded its reach from its traditional heartland in Upper Burma into Lower Burma.

The region's language shift from Mon to Burmese has been ascribed to a combination of population displacement, intermarriage, and voluntary changes in self-identification among increasingly Mon-Burmese bilingual populations in throughout Lower Burma.[8] The shift was certainly accelerated by the fall of the Mon-speaking Restored Hanthawaddy Kingdom in 1757. Following the fall of Pegu (now Bago), many Mon-speaking refugees fled and resettled in what is now modern-day Thailand.[9] By 1830, an estimated 90% of the population in the Lower Burma self-identified as Burmese-speaking Bamars; huge swaths of former Mon-speaking areas, from the Irrawaddy Delta upriver, spanning Bassein (now Pathein) and Rangoon (now Yangon) to Tharrawaddy, Toungoo, Prome (now Pyay) and Henzada (now Hinthada), were now Burmese-speaking.[8] Great Britain's gradual annexation of Burma throughout the 19th century, in addition to concomitant economic and political instability in Upper Burma (e.g., increased tax burdens to the Burmese crown, British rice production incentives, etc.) also accelerated the migration of Burmese speakers from Upper Burma into Lower Burma.[10]

The Mon language has influenced subtle grammatical differences between the varieties of Burmese spoken in Lower and Upper Burma.[11] In Lower Burmese varieties, the verb ပေး ("to give") is colloquially used as a permissive causative marker, like in other Southeast Asian languages, but unlike in other Tibeto-Burman languages.[11] This usage is hardly employed in Upper Burmese varieties, and is considered a sub-standard construct.[11]

In 1972, the New Mon State Party (NMSP) established a Mon national school system, which uses Mon as a medium of instruction, in rebel-controlled areas.[12] The system was expanded throughout Mon State following a ceasefire with the central government in 1995.[12] Mon State now operates a multi-track education system, with schools either using Mon as the primary medium of instruction (called Mon national schools) offering modules on the Mon language in addition to the government curriculum (called "mixed schools").[12] In 2015, Mon language courses were launched state-wide at the elementary level.[13] This system has been recognized as a model for mother-tongue education in the Burmese national education system, because it enables children taught in the Mon language to integrate into the mainstream Burmese education system at higher education levels.[14][12]

In 2013, it was announced that the Mawlamyine-based Thanlwin Times would begin to carry news in the Mon language, becoming Myanmar's first Mon language publication since 1962.[15]

Geographic distribution

Southern Myanmar (comprising Mon State, Kayin State, and Tanintharyi Region), from the Sittaung River in the north to Myeik (Mergui) and Kawthaung in the south, remains a traditional stronghold of the Mon language.[16] However, in this region, Burmese is favored in urban areas, such as Mawlamyine, the capital of Mon State.[16] In recent years, usage of Mon has declined in Myanmar, especially among the younger generation.[17]

While Thailand is home to a sizable Mon population due to historical waves of migration, only a small proportion (estimated to range between 60,000 to 80,000) speak Mon, due to Thaification and the assimilation of Mons into mainstream Thai society.[18] Mon speakers in Thailand are largely concentrated in Ko Kret.[19][18] The remaining contingent of Thai Mon speakers are located in the provinces of Samut Sakhon, Samut Songkhram, Nakhon Pathom, as well the western provinces bordering Myanmar (Kanchanaburi, Phetchaburi, Prachuap Khiri Khan, and Ratchaburi).[18] A small ethnic group in Thailand speak a language closely related to Mon, called Nyah Kur. They are descendants of the Mon-speaking Dvaravati kingdom.[20]

Dialects

Mon has three primary dialects in Burma, coming from the various regions the Mon inhabit. They are the Central (areas surrounding Mottama and Mawlamyine), Bago, and Ye dialects.[18] All are mutually intelligible. Ethnologue lists Mon dialects as Martaban-Moulmein (Central Mon, Mon Te), Pegu (Mon Tang, Northern Mon), and Ye (Mon Nya, Southern Mon), with high mutual intelligibility among them.

Thai Mon has some differences from the Burmese dialects of Mon, but they are mutually intelligible. The Thai varieties of Mon are considered "severely endangered."[20]

Alphabet

The Old Mon script has been dated to the 6th century,[21] with the earliest inscriptions found in Nakhon Pathom and Saraburi (in Thailand). It may be the ancestral script of the modern Mon (or Burma Mon) script, although there is no extant evidence linking the Old Dvaravati Mon script and the Burma Mon script.[22]

The modern Mon alphabet is an adaptation of the Burmese script; it utilizes several letters and diacritics that do not exist in Burmese, such as the stacking diacritic for medial 'l', which is placed underneath the letter.[23] There is a great deal of discrepancy between the written and spoken forms of Mon, with a single pronunciation capable of having several spellings.[16] The Mon script also makes prominent use of consonant stacking, to represent consonant clusters found in the language.

Consonants

The Mon alphabet contains 35 consonants (including a zero consonant), as follows, with consonants belonging to the breathy register indicated in gray:[24][25]

| က k (/kaˀ/) | ခ kh (/kʰaˀ/) | ဂ g (/kɛ̤ˀ/) | ဃ gh (/kʰɛ̤ˀ/) | ၚ ṅ (/ŋɛ̤ˀ/) |

| စ c (/caˀ/) | ဆ ch (/cʰaˀ/) | ဇ j (/cɛ̤ˀ/) | ၛ jh (/cʰɛ̤ˀ/) | ဉ / ည ñ (/ɲɛ̤ˀ/) |

| ဋ ṭ (/taˀ/) | ဌ ṭh (/tʰaˀ/) | ဍ ḍ (/ɗaˀ/~[daˀ]) | ဎ ḍh (/tʰɛ̤ˀ/) | ဏ ṇ (/naˀ/) |

| တ t (/taˀ/) | ထ th (/tʰaˀ/) | ဒ d (/tɛ̤ˀ/) | ဓ dh (/tʰɛ̤ˀ/) | န n (/nɛ̤ˀ/) |

| ပ p (/paˀ/) | ဖ ph (/pʰaˀ/) | ဗ b (/pɛ̤ˀ/) | ဘ bh (/pʰɛ̤ˀ/) | မ m (/mɛ̤ˀ/) |

| ယ y (/jɛ̤ˀ/) | ရ r (/rɛ̤ˀ/) | လ l (/lɛ̤ˀ/) | ဝ w (/wɛ̤ˀ/) | သ s (/saˀ/) |

| ဟ h (/haˀ/) | ဠ ḷ (/laˀ/) | ၜ b (/ɓaˀ/~[baˀ]) | အ a (/ʔaˀ/) | ၝ mb (/ɓɛ̤ˀ/~[bɛ̤ˀ]) |

In the Mon script, consonants belong to one of two registers: clear and breathy, each of which has different inherent vowels and pronunciations for the same set of diacritics. For instance, က, which belongs to the clear register, is pronounced /kaˀ/, while ဂ is pronounced /kɛ̤ˀ/, to accommodate the vowel complexity of the Mon phonology.[26] The addition of diacritics makes this obvious. Whereas in Burmese spellings with the same diacritics are rhyming, in Mon this depends on the consonant's inherent register. A few examples are listed below:

- က + ဳ → ကဳ, pronounced /kɔe/

- ဂ + ဳ → ဂဳ, pronounced /ki̤/

- က + ူ → ကူ, pronounced /kao/

- ဂ + ူ → ဂူ, pronounced /kṳ/

The Mon language has 8 medials, as follows: ္ၚ (/-ŋ-/), ၞ (/-n-/), ၟ (/-m-/), ျ (/-j-/), ြ (/-r-/), ၠ (/-l-/), ွ (/-w-/), and ှ (/-hn-/).

Consonantal finals are indicated with a virama (်), as in Burmese: however, instead of being pronounced as glottal stops as in Burmese, final consonants usually keep their respective pronunciations. Furthermore, consonant stacking is possible in Mon spellings, particularly for Pali and Sanskrit-derived vocabulary.

Vowels

Mon uses the same diacritics and diacritic combinations as in Burmese to represent vowels, with the addition of a few diacritics unique to the Mon script, including ဴ (/ɛ̀a/), and ဳ (/i/), since the diacritic ိ represents /ìˀ/.[27] Also, ဨ (/e/) is used instead of ဧ, as in Burmese.

Main vowels and diphthongs

| Initial or independent symbol | diacritic | Transcription and notes[28][29] |

|---|---|---|

| အ | none, inherent vowel | a or e - /a/, /ɛ̀/ after some consonants |

| အာ | ာ | ā - spelled as ါ to avoid confusion with certain letters |

| ဣ | ိ | i |

| ဣဳ | ဳ | ī or oe - /ì/, /ɔe/ after some consonants |

| ဥ | ု | u |

| ဥူ | ူ | ū or ao - /ù/, /ao/ after some consonants |

| ဨ | ေ | e |

| အဲ | ဲ | ai |

| အော | ော | o - spelled as ေါ to avoid confusion with certain consonants. |

| အဴ | ဴ | āi/oi |

| အံ | ံ | òm |

| အး | း | ah |

Phonology

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stops | p pʰ ɓ~b2 | t tʰ ɗ~d2 | c cʰ | k kʰ | ʔ |

| Fricatives | s | ç1 | h | ||

| Nasals | m | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Sonorants | w | l r | j |

- /ç/ is only found in Burmese loans.

- Implosives are lost in many dialects and become explosives instead.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Close-mid | e | ə | o |

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɐ | ɔ |

| Open | æ | a |

Vocalic register

Unlike the surrounding Burmese and Thai languages, Mon is not a tonal language. As in many Mon–Khmer languages, Mon uses a vowel-phonation or vowel-register system in which the quality of voice in pronouncing the vowel is phonemic. There are two registers in Mon:

- Clear (modal) voice, analyzed by various linguists as ranging from ordinary to creaky

- Breathy voice, vowels have a distinct breathy quality

One study involving speakers of a Mon dialect in Thailand found that in some syllabic environments, words with a breathy voice vowel are significantly lower in pitch than similar words with a clear vowel counterpart.[32] While difference in pitch in certain environments was found to be significant, there are no minimal pairs that are distinguished solely by pitch. The contrastive mechanism is the vowel phonation.

In the examples below, breathy voice is marked with under-diaeresis.

Syntax

Pronouns

| Mon | Translate |

|---|---|

| အဲ | I |

| ဒဒက်တဴကဵုအဲ | My; mine |

| ဟိုန်အဲ | Me |

| မိန်အဲ | By me |

| ကုအဲ | From me |

| ပိုဲ | We |

| ဟိုန်ပိုဲ | Us |

| ဒဒက်တဴကဵုပိုဲ | Our; ours; of us |

| ကုပိုဲ | To us |

| မိန်ပိုဲညးဂမၠိုၚ် | By us |

| နူပိုဲညးဂမၠိုၚ် | From us |

| တၠအဲ၊ ဗှေ် | You; thou |

| ဒဒက်တဴကဵုတၠအဲ | You; yours; thy; thine |

| ဟိုန်တၠအဲ | You; thee |

| မိန်တၠအဲ | By you (Sin); by thee |

| နူတၠအဲ | From you |

| ကုတၠအဲ | To you |

| ၚ်မၞးတံညးဂမၠိုၚ် | You |

| ဟိုန်မၞးတံ | You; (Object) |

| ဒဒက်တဴကဵုမၞးတံ | Your; yours |

| ကုမၞးတံ | To you |

| မိန်မၞးတံ | By you |

| နူမၞးတံ | From you |

| ၚ်ညးဂှ် | He |

| ဒဒက်တဴကဵုညးဂှ် | His |

| ဟိုန်ညးဂှ် | Him |

| ကုညးဂှ် | To him |

| နူညးဂှ် | From him |

| ၚ်ညးတံဂှ် | They |

| ဟိုန်ညးတံဂှ် | Them |

| ဒဒက်တဴကဵုညးတံဂှ် | Their; theirs |

| ကုညးတံဂှ် | To them |

| မိန်ညးတံဂှ် | By them |

| နူညးတံဂှ် | From them |

| ၚ်ညးဗြဴဂှ် | She |

| ကုညးဗြဴဂှ် | Her; hers |

| မိန်ညးဗြဴဂှဲ၊ပ္ဍဲ | By her; in her |

| နူညးဗြဴဂှ် | From her |

| ၚ်ဗြဴတံဂှ် | They (feminine) |

| ဟိုန်ညးဗြဴတံဂှ် | There |

| ကုညးဗြဴတံဂှ် | To them |

| နူညးဗြဴတံဂှ် | From them |

| ပ္ဍဲညးဗြဴတံဂှ် | In them |

Verbs and verb phrases

Mon verbs do not inflect for person. Tense is shown through particles.

Some verbs have a morphological causative, which is most frequently a /pə-/ prefix (Pan Hla 1989:29):

| Underived verb | Gloss | Causative verb | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| chɒt | to die | kəcɒt | to kill |

| lɜm | to be ruined | pəlɒm | to destroy |

| khaɨŋ | to be firm | pəkhaɨŋ | to make firm |

| tɛm | to know | pətɛm | to inform |

Singular and Plural

Mon nouns do not inflect for number. That is, they do not have separate forms for singular and plural:

| ၁ | ||

| sɔt pakaw | mo̤a | me̤a |

| apple | one | classifier |

'one apple'

| ၂ | ||

| sɔt pakaw | ba | me̤a |

| apple | two | classifier |

'two apples'

Adjectives

Adjectives follow the noun (Pan Hla p. 24):

| prɛ̤a | ce |

| woman | beautiful |

'beautiful woman'

Demonstratives

Demonstratives follow the noun:

| ŋoa | nɔʔ |

| day | this |

| this day | |

Classifiers

Like many other Southeast Asian languages, Mon has classifiers which are used when a noun appears with a numeral. The choice of classifier depends on the semantics of the noun involved.

| IPA | kaneh | mo̤a | tanəng |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | pen | one | classifier |

'one pen'

| IPA | chup | mo̤a | tanɒm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gloss | tree | one | classifier |

'one tree'

Prepositions and prepositional phrases

Mon is a prepositional language.

| doa | əma |

| in | lake |

| 'in the lake' |

Sentences

The ordinary word order for sentences in Mon is subject–verb–object, as in the following examples

| Mon | အဲ | ရာန် | သ္ၚု | တုဲ | ယျ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | ʔoa | ran | hau | toa | ya. |

| Gloss | I | buy | rice | completive | affirmative |

'I bought rice.'

| Mon | ညး | တံ | ဗ္တောန် | ကဵု | အဲ | ဘာသာ | အၚ်္ဂလိက် |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Nyeh | tɔʔ | paton | kɒ | ʔua | pʰɛ̤asa | ʔengloit |

| Gloss | 3rd | plur | teach | to | 1st | language | English |

'They taught me English.'

Questions

Yes-no questions are shown with a final particle ha

| Mon | ဗှ်ေ | စ | ပုင် | တုဲ | ယျ | ဟာ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | be̤ | shea | pəng | toa | ya | ha? |

| Gloss | you | eat | rice | com | aff | q |

‘Have you eaten rice?’

| Mon | အပါ | အာ | ဟာ |

|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | əpa | a | ha? |

| Gloss | father | go | q |

‘Will father go?’ (Pan Hla, p. 42)

Wh-questions show a different final particle, rau. The interrogative word does not undergo wh-movement. That is, it does not necessarily move to the front of the sentence:

| Mon | တၠ အဲ | ကြာတ်ကြဴ | မူ | ရော |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IPA | Tala oa | kratkraw | mu | raw? |

| Gloss | You | wash | what | wh:q |

'What did you wash?'

Notes

- Modern Mon at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

Old Mon at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) - "Mon". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- "International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination" (PDF). 28 July 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- "UNESCO Atlas of the World's Languages in danger". UNESCO. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- McCormick, Patrick; Jenny, Mathias (2013-05-13). "Contact and convergence: The Mon language in Burma and Thailand". Cahiers de Linguistique Asie Orientale. 42 (2): 77–117. doi:10.1163/19606028-00422P01. ISSN 1960-6028.

- "The Mon Language". Monland Restoration Council. Archived from the original on 2006-06-22.

- Strachan, Paul (1990). Imperial Pagan: Art and Architecture of Burma. University of Hawaii Press. p. 66. ISBN 0-8248-1325-1.

- Lieberman 2003, p. 202-206.

- Wijeyewardene, Gehan (1990). Ethnic Groups Across National Boundaries in Mainland Southeast Asia. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-3035-57-7.

- Adas, Michael (2011-04-20). The Burma Delta: Economic Development and Social Change on an Asian Rice Frontier, 1852–1941. Univ of Wisconsin Press. pp. 67–77. ISBN 9780299283537.

- Jenny, Mathias (2013). "The Mon language:recipient and donor between Burmese and Thai". Journal of Language and Culture. 31 (2): 5–33. doi:10.5167/uzh-81044. ISSN 0125-6424.

- Lall, Marie; South, Ashley (2014-04-03). "Comparing Models of Non-state Ethnic Education in Myanmar: The Mon and Karen National Education Regimes". Journal of Contemporary Asia. 44 (2): 298–321. doi:10.1080/00472336.2013.823534. ISSN 0047-2336. S2CID 55715948.

- "Mon language classes to launch at state schools". The Myanmar Times. 2015-03-11. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- "Mother tongue education: the Mon model". The Myanmar Times. 2012-08-20. Retrieved 2020-06-03.

- Kun Chan (2013-02-13). "First Mon language newspaper in 50 years to be published". Retrieved 2013-02-16.

- Jenny, Mathias (2001). "A Short Introduction to the Mon Language" (PDF). Mon Culture and Literature Survival Project (MCL). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18. Retrieved 2010-09-30. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (2005). "Mon: A language of Myanmar". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. SIL International. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- South, Ashley (2003). Mon Nationalism and Civil War in Burma: The Golden Sheldrake. Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1609-2.

- Foster, Brian L. (1973). "Ethnic Identity of the Mons in Thailand" (PDF). Journal of the Siam Society. 61: 203–226.

- Moseley, Christopher (2010). Atlas of the World's Languages in Danger. UNESCO. ISBN 978-92-3-104096-2.

- Bauer, Christian (1991). "Notes on Mon Epigraphy". Journal of the Siam Society. 79 (1): 35.

- Aung-Thwin 2005: 177–178

- "Proposal for encoding characters for Myanmar minority languages in the UCS" (PDF). International Organization for Standardization. 2006-04-02. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-07-23. Retrieved 2006-07-09.

- Dho-ong Jhaan (2010-05-09). "Mon Consonants Characters". Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- Dho-ong Jhaan (2009-10-01). "Romanization for Mon Script by Transliteration Method". Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- "Mon". Concise encyclopedia of languages of the world. Elsevier. 2009. pp. 719–20. ISBN 978-0-08-087774-7.

- Dho-ong Jhaan (2010-05-10). "Mon Vowels Characters". Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- Omniglot

- Dho-ong Jhaan (2010-05-10). "Mon Vowels Characters". Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- Omniglot

- Dho-ong Jhaan (2010-05-10). "Mon Vowels Characters". Retrieved 12 September 2010.

- Thongkum, Theraphan L. 1988. The interaction between pitch and phonation type in Mon: phonetic implications for a theory of tonogenesis. Mon-Khmer Studies 16-17:11-24.

Further reading

- Aung-Thwin, Michael (2005). The mists of Rāmañña: The Legend that was Lower Burma (illustrated ed.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824828868.

- Bauer, Christian. 1982. Morphology and syntax of spoken Mon. Ph.D. thesis, University of London (SOAS).

- Bauer, Christian. 1984. "A guide to Mon studies". Working Papers, Monash U.

- Bauer, Christian. 1986. "The verb in spoken Mon". Mon–Khmer Studies 15.

- Bauer, Christian. 1986. "Questions in Mon: Addenda and Corrigenda". Linguistics of the Tibeto-Burman Area v. 9, no. 1, pp. 22–26.

- Diffloth, Gerard. 1984. The Dvarati Old Mon language and Nyah Kur. Monic Language Studies I, Chulalongkorn University, Bangkok. ISBN 974-563-783-1

- Diffloth, Gerard. 1985. "The registers of Mon vs. the spectrographist's tones". UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 60:55-58.

- Ferlus, Michel. 1984. "Essai de phonetique historique du môn". Mon–Khmer Studies, 9:1-90.

- Guillon, Emmanuel. 1976. "Some aspects of Mon syntax". in Jenner, Thompson, and Starosta, eds. Austroasiatic Studies. Oceanic linguistics special publication no. 13.

- Halliday, Robert. 1922. A Mon–English dictionary. Bangkok: Siam society.

- Haswell, James M. 1874. Grammatical notes and vocabulary of the Peguan language. Rangoon: American Baptist Mission Press.

- Huffman, Franklin. 1987–1988. "Burmese Mon, Thai Mon, and Nyah Kur: a synchronic comparison". Mon–Khmer Studies 16–17.

- Jenny, Mathias. 2005. The Verb System of Mon. Arbeiten des Seminars für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft der Universität Zürich, Nr 19. Zürich: Universität Zürich. ISBN 3-9522954-1-8

- Lee, Thomas. 1983. "An acoustical study of the register distinction in Mon". UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics 57:79-96.

- Pan Hla, Nai. 1986. "Remnant of a lost nation and their cognate words to Old Mon Epigraph". Journal of the Siam Society 7:122-155

- Pan Hla, Nai. 1989. An introduction to Mon language. Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University.

- Pan Hla, Nai. 1992. The Significant Role of the Mon Language and Culture in Southeast Asia. Tokyo, Japan: Institute for the Study of Languages and Cultures of Asia and Africa.

- Shorto, H.L. 1962. A Dictionary of Modern Spoken Mon. Oxford University Press.

- Shorto, H.L.; Judith M. Jacob; and E.H.S. Simonds. 1963. Bibliographies of Mon–Khmer and Tai Linguistics. Oxford University Press.

- Shorto, H.L. 1966. "Mon vowel systems: a problem in phonological statement". in Bazell, Catford, Halliday, and Robins, eds. In memory of J.R. Firth, pp. 398–409.

- Shorto, H.L. 1971. A Dictionary of the Mon Inscriptions from the Sixth to the Sixteenth Centuries. Oxford University Press.

- Thongkum, Therapan L. 1987. "Another look at the register distinction in Mon". UCLA Working Papers in Phonetics. 67:132-165

External links

| Mon edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mon language. |

- A hypertext grammar of the Mon language

- SEAlang Project: Mon–Khmer languages: The Monic Branch

- Old Mon inscriptions

- Mon-language Swadesh vocabulary list of basic words (from Wiktionary's Swadesh-list appendix)

- Mon Language Project

- Mon Language in Thailand: The endangered heritage

- "Monic". Archived from the original (lecture) on 2007-09-15. Retrieved 2007-09-21.