Shan language

The Tai Yai language (Tai Yai written: လိၵ်ႈတႆး, pronounced [lik táj] (![]() listen), Tai spoken: ၵႂၢမ်းတႆး, pronounced [kwáːm táj] (

listen), Tai spoken: ၵႂၢမ်းတႆး, pronounced [kwáːm táj] (![]() listen) or ၽႃႇသႃႇတႆး, pronounced [pʰàːsʰàː táj]; Burmese: ရှမ်းဘာသာ, pronounced [ʃáɰ̃ bàðà]; Thai: ภาษาไทใหญ่, pronounced [pʰāː.sǎː.tʰāj.jàj]) is the native language of the Tai people and is mostly spoken in Shan State, Myanmar. It is also spoken in pockets of Kachin State in Myanmar, in Northern Thailand and decreasingly in Assam. Tai Yai is a member of the Tai–Kadai language family and is related to Thai. It has five tones, which do not correspond exactly to Thai tones, plus a "sixth tone" used for emphasis. It is called Tai Yai or Tai Long in the Tai languages.

listen) or ၽႃႇသႃႇတႆး, pronounced [pʰàːsʰàː táj]; Burmese: ရှမ်းဘာသာ, pronounced [ʃáɰ̃ bàðà]; Thai: ภาษาไทใหญ่, pronounced [pʰāː.sǎː.tʰāj.jàj]) is the native language of the Tai people and is mostly spoken in Shan State, Myanmar. It is also spoken in pockets of Kachin State in Myanmar, in Northern Thailand and decreasingly in Assam. Tai Yai is a member of the Tai–Kadai language family and is related to Thai. It has five tones, which do not correspond exactly to Thai tones, plus a "sixth tone" used for emphasis. It is called Tai Yai or Tai Long in the Tai languages.

| Tai Yai | |

|---|---|

| Tai | |

| တႆး | |

| Pronunciation | [lik.táj] |

| Native to | Myanmar, Thailand, China |

| Region | Shan State |

| Ethnicity | Tai Yai |

Native speakers | 3.3 million (2001)[1] |

Kra–Dai

| |

| Burmese script (Shan alphabet) | |

| Official status | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | shn |

| ISO 639-3 | shn |

| Glottolog | shan1277 |

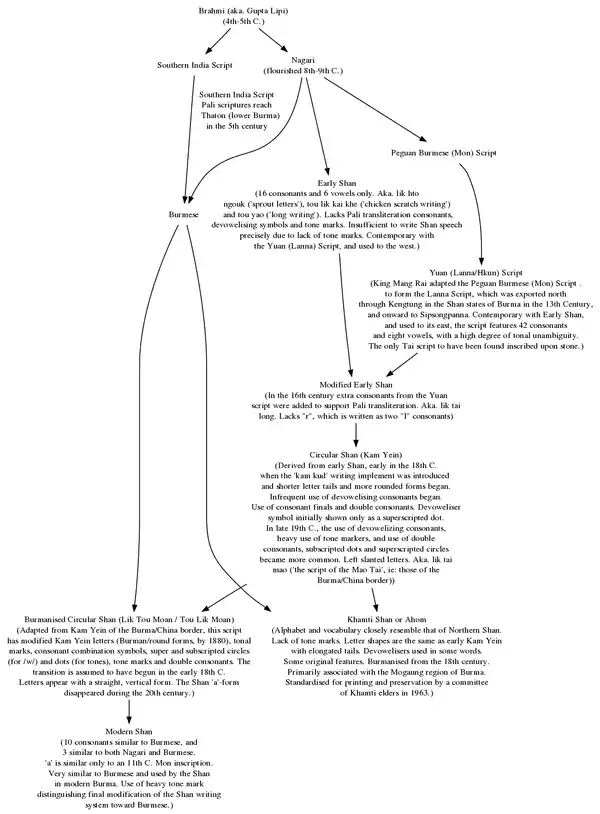

The number of Tai Yai speakers is not known in part because the Tai population is unknown. Estimates of Tai people range from four million to 30 million, with about half speaking the Tai Yai language. In 2001 Patrick Johnstone and Jason Mandryk estimated 3.2 million Shan speakers in Myanmar; the Mahidol University Institute for Language and Culture gave the number of Shan speakers in Thailand as 95,000 in 2006, though including refugees from Burma they now total about one million.[2][3] Many Shan speak local dialects as well as the language of their trading partners. Due to the civil war in Burma, few Shan today can read or write in Shan script, which was derived from the Burmese alphabet.

Names

The Shan language has a number of names in different Tai languages and Burmese.

- In Shan, the language is commonly called kwam tai (ၵႂၢမ်းတႆး, Shan pronunciation: [kwáːm.táj], literally "Tai language").

- In Burmese, it is called shan: bhasa (ရှမ်းဘာသာ, [ʃáɰ̃ bàðà]), whence the English word "Shan". The term "Shan," which was formerly spelt သျှမ်း (hsyam:) in Burmese, is an exonym believed to be a Burmese derivative of "Siam" (an old term for Thailand).

- In Thai and Southern Thai, it is called phasa thai yai (ภาษาไทใหญ่, Thai pronunciation: [pʰāː.sǎː.tʰāj.jàj], literally "big/great Tai language") or more informally or even vulgarly by some phasa ngiao (ภาษาเงี้ยว, Thai pronunciation: [pʰāː.sǎː.ŋía̯w]).

- In Northern Thai, it is called kam tai (กำไต, Northern Thai pronunciation: [kām.tāj], literally "Tai language") or more informally or even vulgarly by some kam ngiao (กำเงี้ยว, Northern Thai pronunciation: [kām.ŋíaw]), literally "Shan language").

- In Lao, it is called phasa tai yai (ພາສາໄທໃຫຍ່, Lao pronunciation: [pʰáː.sǎː.tʰáj.ɲāj], literally "big/great Tai language") or phasa tai nuea (ພາສາໄທເໜືອ, Lao pronunciation: [pʰáː.sǎː.tʰáj.nɯ̌a], literally "Northern Tai language") or more informally or even vulgarly by some phasa ngiao (ພາສາງ້ຽວ, Lao pronunciation: [pʰáː.sǎː.ŋîaw]).

- In Tai Lü, it is called kam ngio (ᦅᧄᦇᦲᧁᧉ, Tai Lue pronunciation: [kâm.ŋìw]).

Dialects

The Shan dialects spoken in Shan State can be divided into three groups, roughly coinciding with geographical and modern administrative boundaries, namely the northern, southern, and eastern dialects. Dialects differ to a certain extent in vocabulary and pronunciation, but are generally mutually intelligible. While the southern dialect has borrowed more Burmese words, Eastern Shan is somewhat closer to northern Thai languages and Lao in vocabulary and pronunciation, and the northern so-called "Chinese Shan" is much influenced by the Yunnan-Chinese dialect. A number of words differ in initial consonants. In the north, initial /k/, /kʰ/ and /m/, when combined with certain vowels and final consonants, are pronounced /tʃ/ (written ky), /tʃʰ/ (written khy) and /mj/ (written my). In Chinese Shan, initial /n/ becomes /l/. In southwestern regions /m/ is often pronounced as /w/. Initial /f/ only appears in the east, while in the other two dialects it merges with /pʰ/.

Prominent dialects are considered as separate languages, such as Khün (called Kon Shan by the Burmese), which is spoken in Kengtung valley, and Tai Lü. Chinese Shan is also called (Tai) Mao, referring to the old Shan State of Mong Mao. 'Tai Long' is used to refer to the dialect spoken in southern and central regions west of the Salween River. There are also dialects still spoken by a small number of people in Kachin State and Khamti spoken in northern Sagaing Region.

J. Marvin Brown (1965)[4] divides the three dialects of Shan as follows:

- Northern — Lashio, Burma; contains more Chinese influences

- Southern — Taunggyi, Burma (capital of Shan State); contains more Burmese influences

- Eastern — Kengtung, Burma (in the Golden Triangle); closer to Northern Tai and Lao

Phonology

Consonants

Shan has 19 consonants. Unlike Thai and Lao there are no voiced plosives [d] and [b].

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Glottal | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unaspirated | Aspirated | Voiced | Unaspirated | Aspirated | Voiced | Unaspirated | Aspirated | Voiced | Unaspirated | Aspirated | Voiced | |||

| Stop | [p] ပ |

[pʰ] ၽ |

[t] တ |

[tʰ] ထ |

[c] ၸ |

[k] ၵ |

[kʰ] ၶ |

[ʔ]1 ဢ | ||||||

| Nasal | [m] မ |

[n] ၼ |

[ɲ] ၺ |

[ŋ] င |

||||||||||

| Fricative | ([f])2 ၾ |

[s] သ |

[h] ႁ | |||||||||||

| Trill | ([r])3 ရ |

|||||||||||||

| Approximant | [j] ယ |

[w] ဝ |

||||||||||||

| Lateral | [l] လ |

|||||||||||||

- 1 The glottal plosive is implied after a short vowel without final, or the silent 'a' before a vowel.

- 2 Initial [f] is only found in eastern dialects in words that are pronounced with [pʰ] elsewhere.

- 3 The trill is very rare and mainly used in Pali and some English loan words, sometimes as a glide in initial consonant clusters. Many Shans find it difficult to pronounce [r], often pronouncing it [l].

Vowels and diphthongs

Shan has ten vowels and 13 diphthongs:

| Front | Central-Back | Back |

|---|---|---|

| /i/ | /ɨ/~/ɯ/ | /u/ |

| /e/ | /ə/~/ɤ/ | /o/ |

| /ɛ/ | /a/ /aː/ | /ɔ/ |

[iu], [eu], [ɛu]; [ui], [oi], [ɯi], [ɔi], [əi]; [ai], [aɯ], [au]; [aːi], [aːu]

Shan has less vowel complexity than Thai, and Shan people learning Thai have difficulties with sounds such as "ia," "ua," and "uea" [ɯa]. Triphthongs are absent. Shan has no systematic distinction between long and short vowels characteristic of Thai.

Tones

Shan has phonemic contrasts among the tones of syllables. There are five to six tonemes in Shan, depending on the dialect. The sixth tone is only spoken in the north; in other parts it is only used for emphasis.

Contrastive tones in unchecked syllables

The table below presents six phonemic tones in unchecked syllables, i.e. closed syllables ending in sonorant sounds such as [m], [n], [ŋ], [w], and [j] and open syllables.

| No. | Description | IPA | Description | Transcription* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | rising (24) | ˨˦ | Starting rather low and rising pitch | ǎ | a (not marked) |

| 2 | low (11) | ˩ | Low, even pitch | à | a, |

| 3 | mid(-falling) (32) | ˧˨ | Medium level pitch, slightly falling in the end | a (not marked) | a; |

| 4 | high (55) | ˥ | High, even pitch | á | a: |

| 5 | falling (creaky) (42) | ˦˨ˀ | Short, creaky, strongly falling with lax final glottal stop | âʔ, â̰ | a. |

| 6 | emphatic (343) | ˧˦˧ | Starting mid level, then slightly rising, with a drop at the end (similar to tones 3 and 5) | a᷈ | |

- * The symbol in the first column corresponds to conventions used for other tonal languages; the second is derived from the Shan orthography.

The following table shows an example of the phonemic tones:

| Tone | Shan | IPA | Transliteration | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rising | ၼႃ | /nǎː/ | na | thick |

| low | ၼႃႇ | /nàː/ | na, | very |

| mid | ၼႃႈ | /nāː/ | na; | face |

| high | ၼႃး | /náː/ | na: | paddy field |

| creaky | ၼႃႉ | /na̰/ | na. | aunt, uncle |

The Shan tones correspond to Thai tones as follows:

- The Shan rising tone is close to the Thai rising tone.

- The Shan low tone is equivalent to the Thai low tone.

- The Shan mid-tone is different from the Thai mid-tone. It falls in the end.

- The Shan high tone is close to the Thai high tone. But it is not rising.

- The Shan falling tone is different from the Thai falling tone. It is short, creaky and ends with a glottal stop.

Contrastive tones in checked syllables

The table below presents four phonemic tones in checked syllables, i.e. closed syllables ending in a glottal stop [ʔ] and obstruent sounds such as [p], [t], and [k].

| Tone | Shan | Phonemic | Phonetic | Transliteration | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| high | လၵ်း | /lák/ | [lak˥] | lak: | post |

| creaky | လၵ်ႉ | /la̰k/ | [la̰k˦˨ˀ] | lak. | steal |

| low | လၢၵ်ႇ | /làːk/ | [laːk˩] | laak, | differ from others |

| mid | လၢၵ်ႈ | /lāːk/ | [laːk˧˨] | laak; | drag |

Syllable structure

The syllable structure of Shan is C(G)V((V)/(C)), which is to say the onset consists of a consonant optionally followed by a glide, and the rhyme consists of a monophthong alone, a monophthong with a consonant, or a diphthong alone. (Only in some dialects, a diphthong may also be followed by a consonant.) The glides are: -w-, -y- and -r-. There are seven possible final consonants: /ŋ/, /n/, /m/, /k/, /t/, /p/, and /ʔ/.

Some representative words are:

- CV /kɔ/ also

- CVC /kàːt/ market

- CGV /kwàː/ to go

- CGVC /kwaːŋ/ broad

- CVV /kǎi/ far

- CGVV /kwáːi/ water buffalo

Typical Shan words are monosyllabic. Multisyllabic words are mostly Pali loanwords, or Burmese words with the initial weak syllable /ə/.

Alphabet

The Shan script is characterised by its circular letters, which are very similar to those of the Mon script. The old Shan script used until the 1960s did not differentiate all vowels and diphthongs and had only one tone marker and a single form could represent up to 15 sounds. Only the well-trained were able to read Shan. This has been fixed, making the modern Shan alphabet easy to read, with all tones indicated unambiguously. The standard Shan script is an abugida, all letters having an inherent vowel a. Vowels are represented in the form of diacritics placed around the consonants.

The Shan alphabet is much less complex than the Thai one and lacks the notions of high-class, mid-class and low-class consonants, distinctions which help the Thai alphabet to number some 44 consonants. Shan has only 19 consonants and all tones are clearly indicated with unambiguous tonal markers at the end of the syllable (in the absence of any marker, the default is the rising tone).

The number of consonants in a textbook may vary: there are 19 universally accepted Shan consonants (ၵ ၶ င ၸ သ ၺ တ ထ ၼ ပ ၽ ၾ မ ယ ရ လ ဝ ႁ ဢ) and five more which represent sounds not found in Shan, g, z, b, d and th ([θ] as in "thin"). These five (ၷ ၹ ၿ ၻ ႀ) are quite rare. In addition, most editors include a dummy consonant used to support leading vowels. A textbook may therefore present 18-24 consonants.

| ၵ ka (ka) | ၶ kha (kʰa) | င nga (ŋa) | ၸ tsa (ca) | သ sa (sa) | ၺ nya (ɲa) | ||

| တ ta (ta) | ထ tha (tʰa) | ၼ na (na) | ပ pa (pa) | ၽ pha (pʰa) | ၾ fa (fa) | ||

| မ ma (ma) | ယ ya (ja) | ရ ra (ra) | လ la (la) | ဝ wa (wa) | ႁ ha (ha) | ||

| ဢ a (ʔa) | |||||||

| Final consonants and other symbols | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| မ် (m) | ၼ် (n) |

င် (ŋ) | ပ် (p) |

တ် (t) | ၵ် (k) |

ျ (ʃa) | ြ (pʰra) |

The representation of the vowels depends partly on whether the syllable has a final consonant. They have been arranged in a manner to show the logical relationships between the medial and the final forms and between the individual vowels and the vowel clusters they help form.

| Medial Vowels | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ဢ a (a) | ၢ aa (ɑː) | ိ i (i) | ဵ e (e) | ႅ ae (æ) | ု u (u) | ူ o (o) | ွ aw/o (ɔ) | ို eu (ɯ) | ိူ oe (ə) | ႂ[6] wa (ʷ) |

| Final Vowels | ||||||||||

| ႃ aa (ɑː) | ီ ii (iː) | ေ e (e) | ႄ ae (æ) | ူ uu (uː) | ူဝ် o (o) | ေႃ aw/o (ɔ) | ိုဝ် eu (ɯ) | ိူဝ် oe(ə) | ||

| ႆ ai (ai) | ၢႆ aai (aːi) | ုၺ် ui (ui) | ူၺ် ohi/uai (oi) | ွႆ oi/oy (ɔi) | ိုၺ် uei/uey (ɨi) | ိူၺ် oei/oey (əi) | ||||

| ဝ် aw (au) | ၢဝ် aaw (aːu) | ိဝ် iu (iu) | ဵဝ် eo(eu) | ႅဝ် aeo (æu) | ႂ် aɨ (aɯ) | |||||

The tones are indicated by tone markers at the end of the syllable (represented by a dash in the following table), namely:

| Sign | Name | Tone |

|---|---|---|

| ႇ | ယၵ်း (ják) | 2 |

| ႈ | ယၵ်းၸမ်ႈ (ják tsam) | 3 |

| း | ၸမ်ႈၼႃႈ (tsam naː) | 4 |

| ႉ | ၸမ်ႈတႂ်ႈ (tsam tau) | 5 |

| ႊ | ယၵ်းၶိုၼ်ႈ (ják kʰɯn) | 6 |

While the reformed script originally used only four diacritic tone markers, equivalent to the five tones spoken in the southern dialect, the Lashio-based Shan Literature and Culture Association now, for a number of words, promotes the use of the 'yak khuen' to denote the sixth tone as pronounced in the north.

Two other scripts are also still used to some extent. The so-called Lik To Yao ('long letters'), which derives from Lik Tai Mao or Lik Hto Ngouk ('bean sprout script'), the old script of the Mao or Chinese Shans, may be used in the north. In this systems, vowel signs are written behind the consonants.

Pronouns

| Person | Pronoun | IPA | Meaning[7] |

|---|---|---|---|

| first | ၵဝ် | kǎw | I/me (informal) |

| တူ | tǔ | I/me (informal) | |

| ၶႃႈ | kʰaː | I/me (formal) "servant, slave" | |

| ႁႃး | háː | we/us two (familiar/dual) | |

| ႁဝ်း | háw | we/us (general) | |

| ႁဝ်းၶႃႈ | háw.kʰaː | we/us (formal) "we servants, we slaves" | |

| second | မႂ်း | máɰ | you (informal/familiar) |

| ၸဝ်ႈ | tsaw | you (formal) "master, lord" | |

| ၶိူဝ် | kʰə̌ə | you two (familiar/dual) | |

| သူ | sʰǔ | you (formal/singular, general/plural) | |

| သူၸဝ်ႈ | sʰǔ.tsaw | you (formal/singular, general/plural) "you masters, you lords" | |

| third | မၼ်း | mán | he/she/it (informal/familiar) |

| ၶႃ | kʰǎa | they/them two (familiar/dual) | |

| ၶဝ် | kʰǎw | he/she/it (formal), or they/them (general) | |

| ၶဝ်ၸဝ်ႈ | kʰǎw.tsaw | he/she/it (formal), or they/them (formal) "they masters, they lords" | |

| ပိူၼ်ႈ | pɤn | they/them, others |

Resources

Given the present instabilities in Burma, one choice for scholars is to study the Shan people and their language in Thailand, where estimates of Shan refugees run as high as two million, and Mae Hong Son Province is home to a Shan majority. The major source for information about the Shan language in English is Dunwoody Press's Shan for English Speakers. They also publish a Shan-English dictionary. Aside from this, the language is almost completely undescribed in English.

References

- Tai Yai at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015)

- "Shan". Ethnologue. Retrieved Apr 27, 2020.

- https://www.bnionline.net/en/news/refugee-conundrum-little-movement-myanmars-repatriation-schemes

- Brown, J. Marvin. 1965. From Ancient Thai To Modern Dialects and Other Writings on Historical Thai Linguistics. Bangkok: White Lotus Press, reprinted 1985.

- Ager, Simon. "Shan alphabet, pronunciation and language". Omniglot. Retrieved 28 December 2018.

- "Data" (PDF). unicode.org. Retrieved 2020-06-22.

- "SEAlang Library Shan Lexicography". sealang.net. Retrieved Apr 27, 2020.

Further reading

- Sai Kam Mong. The History and Development of the Shan Scripts. Chiang Mai, Thailand: Silkworm Books, 2004. ISBN 974-9575-50-4

- The Major Languages of East and South-East Asia. Bernard Comrie (London, 1990).

- A Guide to the World's Languages. Merritt Ruhlen (Stanford, 1991).

- Shan for English Speakers. Irving I. Glick & Sao Tern Moeng (Dunwoody Press, Wheaton, 1991).

- Shan - English Dictionary. Sao Tern Moeng (Dunwoody Press, Kensington, 1995).

- An English and Shan Dictionary. H. W. Mix (American Baptist Mission Press, Rangoon, 1920; Revised edition by S.H.A.N., Chiang Mai, 2001).

- Grammar of the Shan Language. J. N. Cushing (American Baptist Mission Press, Rangoon, 1887).

- Myanmar - Unicode Consortium

External links

| Shan edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |