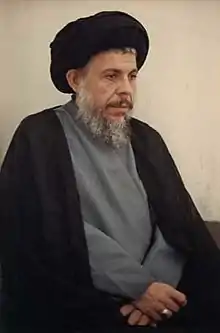

Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr

Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr (Arabic: آية الله العظمى السيد محمد باقر الصدر, March 1, 1935 – April 9, 1980), also known as al-Shahīd al-Khāmis, was an Iraqi Shia cleric, philosopher, and the ideological founder of the Islamic Dawa Party, born in al-Kadhimiya, Iraq. He was father-in-law to Muqtada al-Sadr, a cousin of Muhammad Sadeq al-Sadr and Imam Musa as-Sadr. His father Haydar al-Sadr was a well-respected high-ranking Shi'a cleric. His lineage can be traced back to Muhammad through the seventh Shia Imam Musa al-Kazim. Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr was executed in 1980 by the regime of Saddam Hussein along with his sister, Amina Sadr bint al-Huda.

Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | March 1, 1935 |

| Died | April 9, 1980 (aged 45) Baghdad, Iraq |

| Resting place | Wadi-us-Salaam, Najaf |

| Religion | Islam |

| Nationality | Iraqi |

| Citizenship | Iraq |

| Sect | Usuli Twelver Shia Islam |

| Muslim leader | |

| Based in | Najaf, Iraq |

| Post | Grand Ayatollah |

| Part of a series on Shia Islam |

| Twelvers |

|---|

|

|

Biography

Early life and education

Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr was born in al-Kazimiya, Iraq to the prominent Sadr family, which originated from Jabal Amel in Lebanon. His father died in 1937, leaving the family destitute. In 1945, the family moved to the holy city of Najaf, where al-Sadr would spend the rest of his life. He was a child prodigy who, at 10, was delivering lectures on Islamic history. At eleven, he was a student of logic. He wrote a book refuting materialistic philosophy when he was 24.[1] Al-Sadr completed his religious studies at religious seminaries under al-Khoei and Muhsin al-Hakim, and began teaching at the age of 25.

Later life

Al-Sadr's works attracted the ire of the Baath Party leading to repeated imprisonment where he was often tortured. Despite this, he continued his work after being released.[2] When the Baathists arrested Ayatollah Al-Sadr in 1977, his sister Amina Sadr bint al-Huda made a speech in the Imam Ali mosque in Najaf inviting the people to demonstrate. Many demonstrations were held, forcing the Baathists to release Al-Sadr who was placed under house arrest.

In 1979–1980, anti-Ba'ath riots arose in Iraq's Shia areas by groups who were working toward an Islamic revolution in their country.[3] Saddam and his deputies believed that the riots had been inspired by the Iranian Revolution and instigated by Iran's government.[4] In the aftermath of Iran's revolution, Iraq's Shia community called on Mohammad Baqir al-Sadr to be their “Iraqi Ayatollah Khomeini”, leading a revolt against the Ba'ath regime.[5][6] Community leaders, tribal heads, and hundreds of ordinary members of the public paid their allegiance to al-Sadr.[5] Protests then erupted in Baghdad and the predominantly Shia provinces of the south in May 1979.[5] For nine days, protests against the regime unfolded, but were suppressed by the regime.[5] The cleric's imprisonment led to another wave of protests in June after a seminal, powerful appeal from al-Sadr's sister, Bint al-Huda. Further clashes unfolded between the security forces and protestors. Najaf was put under siege and thousands were tortured and executed.[5]

Execution

Baqir al-Sadr was finally arrested on April 5, 1980 with his sister, Sayyidah Bint al-Huda.[7] They had formed a powerful militant movement in opposition to Saddam Hussein's regime.[8]

On April 9, 1980, Al-Sadr and his sister were killed after being severely tortured by their Baathist captors.[2] Signs of torture could be seen on the bodies.[8][9][10]

An iron nail was hammered into Al-Sadr's head and he was then set on fire in Najaf.[2][7] It has been reported that Saddam himself killed them.[8] The Baathists delivered the bodies of Baqir al-Sadr and Bint al-Huda to their cousin Sayyid Muhammad al-Sadr.[8]

They were buried in the Wadi-us-Salaam graveyard in the holy city of Najaf the same night.[7] His execution raised no criticism from Western countries because Al-Sadr had openly supported Ayatollah Khomeini in Iran.[9]

Scholarship

The works by Baqir al-Sadr contains traditional Shia thoughts, while they also suggest ways Shia could "accommodate modernity". The two major works by him are Iqtisaduna on Islamic economics, and Falsafatuna (Our Philosophy).[11] They were detailed critiques of Marxism that presented his early ideas on an alternative Islamic form of government. They were critiques of both socialism and capitalism. He was subsequently commissioned by the government of Kuwait to assess how that country's oil wealth could be managed in keeping with Islamic principles. This led to a major work on Islamic banking, which still forms the basis for modern Islamic banks.[12]

Using his knowledge of the Quran and a subject-based approach to Quranic exegesis, Al-Sadr extracted two concepts from the Holy text in relation to governance: khilafat al-insan (Man as heir or trustee of God) and shahadat al-anbiya (Prophets as witnesses). Al-Sadr explained that throughout history there have been "...two lines. Man's line and the Prophet's line. The former is the khalifa (trustee) who inherits the earth from God; the latter is the shahid (witness)".[13]

Al-Sadr demonstrated that khilafa (governance) is "a right given to the whole of humanity" and defined it as an obligation given from God to the human race to "tend the globe and administer human affairs". This was a major advancement of Islamic political theory.[14]

While Al-Sadr identified khilafa as the obligation and right of the people, he used a broad-based explanation of a Quranic verse [15] to identify who held the responsibility of shahada in an Islamic state. First were the Prophets (anbiya'). Second were the Imams who are considered a divine (rabbani) continuation of the Prophets in this line. The last were the marja'iyya (see Marja).[16]

While the two functions of khilafa and shahada (witness; supervision) were united during the times of the Prophets, they diverged during the occultation so that khilafa returned to the people (umma) and shahada to the scholars.[17]

Al-Sadr also presented a practical application of khilafa, in the absence of the twelfth Imam. He argued that khilafa required the establishment of a democratic system whereby the people regularly elect their representatives in government:

Islamic theory rejects monarchy as well as the various forms of dictatorial government; it also rejects the aristocratic regimes and proposes a form of government, which contains all the positive aspects of the democratic system.[18]

He continued to champion this point until his final days:

Lastly, I demand, in the name of all of you and in the name of the values you uphold, to allow the people the opportunity truly to exercise their right in running the affairs of the country by holding elections in which a council representing the ummah (people) could truly emerge.' [19]

Al-Sadr was executed by Saddam Hussein in 1980 before he was able to provide any details of the mechanism for the practical application of the shahada concept in an Islamic state. A few elaborations of shahada can be found in Al-Sadr's works. In his text Role of the Shiah Imams in the Reconstruction of Islamic Society, Al-Sadr illustrates the scope and limitations of shahada by using the example of the third Shi'i Imam, Hussein ibn Ali (the grandson of the Prophet), who defied Yazid, the ruler at the time. Al-Sadr explained that Yazid was not simply acting counter to Islamic teachings, as many rulers before and after him had done, but he was distorting the teachings and traditions of Islam and presenting his deviant ideas as representative of Islam itself. This, therefore, is what led Imam Hussein to intervene challenging Yazid in order to restore the true teachings of Islam, and consequently laying down his own life. In Al-Sadr's own words, the shahid's (witness – person performing shahada or supervision) duties are "to protect the correct doctrines and to see that deviations do not grow to the extent of threatening the ideology itself".[20]

List of works

Al-Sadr engaged Western philosophical ideas, challenging them as necessary and incorporating them where appropriate, with the ultimate goal of demonstrating that religious knowledge was not antithetical to scientific knowledge.[21] The following is a list of his work:[22]

Jurisprudence

- Buhuth fi Sharh al- 'Urwah al' Wuthqa (Discourses on the Commentary of al- 'Urwah al-Wuthqa), four volumes

- Al-Ta'liqah 'ala Minhaj al-Salihin (Annotation of Ayatullah Hakim's Minhaj al-Salihin), two volumes

- Al-Fatawa al-Wadhihah (Clear Decrees).

- Mujaz Ahkam al-Hajj (Summarized Rules of Hajj)

- Al-Ta'liqah 'ala Manasik al-Hajj (Annotation of Ayatullah Khui's Hajj Rites)

- Al-Ta'liqah 'ala Salah al-Jumu'ah (Annotation on Friday Prayer)

Fundamentals of the law

- Durus fi Ilm al-Usul (Lessons in the Science of Jurisprudence), 3 Parts.[23]

- Al-Ma'alim al-Jadidah lil-Usul (The New Signposts of Jurisprudence)

- Ghayat al-Fikr (The Highest Degree of Thought)

Philosophy

- Falsafatuna () (Our Philosophy) published in 1959

Logic

- Al-Usus al-Mantiqiyyah lil-Istiqra' (Logical Foundations of Induction)

Theology

- Al-Mujaz fi Usul al-Din: al-Mursil, al-Rasul, al-Risalah (The Summarized Principles of Religion: The Sender, The Messenger, The Message)

- Al-Tashayyu' wa al-Islam - Bahth Hawl al-Wilayah (Discourse on Divine Authority)

- Bahth Hawl al-Mahdi (Discourse on Imam Mahdi)

Economics

- Iqtisaduna (Our Economy)

- Al-Bank al-la Ribawi fi al-Islam (Usury-free Banking in Islam)

- Maqalat Iqtisadiyyah (Essays in Economy)

Qur'anic commentaries

- Al-Tafair al-Mawzu'i lil-Qur'an al-Karim - al-Madrasah al-Qur'aniyyah (The Thematic Exegesis of the Holy Qur'an)

- 1Buhuth fi 'Ulum al-Qur'an (Discourses on Qur'anic Sciences)

- Maqalat Qur'aniyyah (Essays on Qur'an)

History

- Ahl al-Bayt Tanawwu' Ahdaf wa Wahdah Hadaf (Ahl al- Bayt, Variety of Objectives Towards a Single Goal)

- Fadak fi al-Tarikh (Fadak in History)

Islamic culture

- Al-Islam Yaqud al-Hayah (Islam Directive to Life)

- Al-Madrasah al-Islamiyyah (Islamic School)

- Risalatuna (Our Mission)

- Nazrah Ammah fi al-Ibadat (General View on Rites of Worship)

- Maqalat wa Muhazrat (Essays and Lectures)

Articles

- "Al-'Amal wa al-Ahdaf" (The Deeds and the Goals): Min Fikr al- Da'wah. No. 13. Islamic Da'wah Party, central propagation, place and date of publication unknown.

- "Al-'Amal al-Salih fi al-Quran" (The Proper Deeds According to Qur'an): Ikhtrna Lak. Beirut: Dar al-Zahra', 1982

- "Ahl al-Bayt: Tanawu' Adwar wa-Wihdat Hadaf" (The Household of the Prophet: Diversity of Roles But Unified Goal). Beirut: Dar al-Ta'ruf, 1985.

- "Bahth Hawla al-Mahdi" (Thesis on Messiah). Beirut: Dar al- Ta'ruf, 1983.

- "Bahth Hawla al-Wilayah" (Thesis on Rulership). Kuwait: Dar al- Tawhid, 1977.

- "Da'watana il al-Islam Yajeb an Takun Enqilabiyah," (Our Call for Islam Must be Revolutionary): Fikr al-Da'wah, No. 13. Islamic Da'wah Party, central propagation, place and date of publication unknown.

- "Dawr al-A'imah fi al-Hayat al-Islamiyah" (The Role of Imams in Muslims' Life): Ikhtarna Lak. Beirut: Dar al-Zahra', 1982

- "al-Dawlah al-Islamiyah" (The Islamic State), al-Jihad (March 14, 1983): 5

- "Hawla al-Marhala al-Ula min 'Amal al-Da'wah" (On the First Stage of Da'wah Political Program): Min Fikr al-Da'wah. No. 13. Islamic Da'wah Party, central propagation, place and date of publishing unknown.

- "Hawla al-Ism wa-al-Shakl al-Tanzimi li-Hizb al-Da'wah al- Islamiyah" (On the Name and the Structural Organization of the Islamic Da'wah Party): Min Fikr al-Da'wah. No. 13. Islamic Da'wah Party, central propagation, place and date of publication unknown.

- "al-Huriyah fi al-Quran" (Freedom According to the Quran): Ikhtarna Lak. Beirut: Dar al-Zahra', 1982

- "al-Itijahat al-Mustaqbaliyah li-Harakat al-Ijtihad" (The Future Trends of the Process of Ijtihad): Ikhtarna Lak. Beirut: Dar al-Zahra', 1980.

- "al-Insan al-Mu'asir wa-al-Mushkilah al-Ijtima'yah" (Contemporary Man and the Social Problem)

- "al-Janib al-Iqtisadi Min al-Nizam al-Islami" (The Economic Perspective of the Islamic System): Ikhtarna Lak. Beirut: Dar al-Zahra', 1982

- "Khalafat al-Insan wa-Shahadat al-Anbia'" (Victory Role of Man, and Witness Role of Prophets): al-Islam Yaqwod al-Hayat. Iran: Islamic Ministry of Guidance, n.d.

- "Khatut Tafsiliyah 'An Iqtisad al-Mujtama' al-Islami (General Basis of Economics of Islamic Society): al-Islam Yaqud al-Hayah. Iran: Islamic Ministry of Guidance, n.d.

- "Lamha fiqhiyah Hawla Dustur al-Jumhuriyah al-Islamiyah" (A Preliminary Jurisprudence Basis of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic): al-Islam Yaqwod al-Hayat Iran: Islamic Ministry of Guidance, n.d.

- "Madha Ta'ruf 'an al-Iqtisad al-Islami" (What Do You Know About Islamic Economics). al-Islam Yaqwod al-Hayat Iran: Islamic Ministry of Guidance, n.d.

- "Manabi' al-Qudra fi al-Dawlah al-Islamiyah" (The Sources of Power in an Islamic State). al-Islam Yaqwod al-Hayat Iran: Islamic Ministry of Guidance, n.d.

- "al-Mihna" (The Ordeal). Sawt al-Wihdah, Nos. 5, 6, 7. (n.d)

- "Minhaj al-Salihin" (The Path of the Righteous). Beirut: Dar al- Ta'aruf, 1980.

- "Muqaddimat fi al-Tafsir al-Mawdu'i Lil-Quran" (Introductions in Thematic Exegesis of the Quran). Kuwait: Dar al- Tawjyyh al-Islami, 1980.

- "Nazarah 'Amah fi al-'Ibadat" (General Outlook on Worship): al-Fatawa al-Wadhiha. Beirut: Dar al-Ta'aruf, 1981.

- "al-Nazriyah al-Islamiyah li-Tawzi' al-Masadr al-Tabi'iyah" (Islamic Theory of Distribution of Natural Resources): Ikhtarna Lak. Beirut: Dar al-Zahra', 1982.

- "al-Nizam al-Islami Muqaranan bil-Nizam al-Ra'smali wa-al- Markisi" (The Islamic System Compared with The Capitalist and The Marxist Systems). Ikhtarna Lak. Beirut: Dar-al Zahra', 1982.

- "Risalatuna wa-al-Da'wah" (Our Message and Our Sermon). Risalatuna. Beirut: al-Dar al-Islamiyah, 1981.

- "Al-Shakhsiyah al-Islamiyah" (Muslim Personality): Min Fikr al-Da'wah al-Islamiyah (Of the Thoughts of Islamic Da'wah). No. 13. Islamic Da'wah Party, central propagation, place and date of publication unknown.

- "Surah 'An Iqtisad al-Mujtama' al-Islami" (A Perspective on the Economy of Muslim Society). al-Islam Yaqwod al-Hayat Iran: Islamic Ministry of Guidance, n.d.

- "al-Usus al-Amah li-al-Bank fi al-Mujtam al-Islami" (The General Basis of Banks in Islamic Society). in al-Islam Yaqwod al-Hayat Iran: Islamic Ministry of Guidance, n.d.

- "Utruhat al-Marja'iyah al-Salihah" (Thesis on Suitable Marja'iyah). In Kazim al-Ha'iri, Mabahith fi 'Ilm al-Usul.Qum, Iran: n.p., 1988.

- "al-Yaqin al-Riyadi wa-al-Mantiq al-Waz'i" (The Mathematic Certainty and the Phenomenal Logic): Ikhtrna Lak. Beirut: Dar al-Zahra', 1982.

- "Preface to al-Sahifah al-Sajadiyah" (of Imam Ali ibn Hussein al-Sajad) Tehran: al-Maktabah al-Islamiyah al-Kubra, n.d.

Notable colleagues and students

Books

See also

References

- Baqir Al-Sadr, Our Philosophy, Taylor and Francis, 1987, p. xiii

- Al Asaad, Sondoss (April 9, 2018). "38 Years After Saddam's Heinous Execution of the Phenomenal Philosopher Ayatollah Al-Sadr and his Sister". moderndiplomacy.eu. Modern Diplomacy. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Karsh, Efraim (April 25, 2002). The Iran–Iraq War: 1980–1988. Osprey Publishing. pp. 1–8, 12–16, 19–82. ISBN 978-1841763712.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (December 20, 2011). Iran at War: 1500–1988. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. ISBN 978-1-78096-221-4.

- "Iraq's failed uprising after the 1979 Iranian revolution". March 11, 2019.

- Cockburn, Patrick (2008). Muqtada Al-Sadr and the Battle for the Future of Iraq. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-4119-9. Retrieved March 24, 2020.

- Al Asaad, Sondoss (April 10, 2018). "The ninth of April, the martyrdom of the Sadrs". tehrantimes.com. Tehran Times. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Ramadani, Sami (August 24, 2004). "There's more to Sadr than meets the eye". theguardian.com. The Guardian. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Aziz, T.M (May 1, 1993). "The Role of Muhammad Baqir al-Sadr in Shii Political Activism in Iraq from 1958 to 1980". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 25 (2): 207–222. doi:10.1017/S0020743800058499. JSTOR 164663.

- Marlowe, Lara (January 6, 2007). "Sectarianism laid bare". irishtimes.com. The Irish Times. Retrieved March 9, 2019.

- Nasr, Seyyed Husain (1989). Expectation of the Millennium: Shi'ism in History. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-88706-843-0. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Behdad, Sohrab; Nomani, Farhad (2006). Islam and the Everyday World: Public Policy Dilemmas. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-20675-9. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Muhammed Baqir Al-Sadr, Al-Islam yaqud al-hayat, Qum, 1979, p.132

- Walberg, Eric (2013). From Postmodernism to Postsecularism: Re-emerging Islamic Civilization. SCB Distributors. ISBN 978-0-9860362-4-8. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Quran 5:44

- Baqir Al-Sadr, Al-Islam yaqud al-hayat, Qum, 1979, p.24

- Faleh A Jabar, The Shi'ite Movement in Iraq, London: Saqi Books, 2003, p.286

- Muhammed Baqir Al-Sadr, Lamha fiqhiya, p.20

- Muhammed Baqir Al-Sadr, Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence, London: ICAS, 2003, p.15

- Hadad, Sama (2008). "The Development of Shi'ite Islamic Political Theory". Dissent and Reform in the Arab World. American Enterprise Institute: 32–40. Retrieved March 22, 2020.

- Walbridge, Linda S. (2001). The Most Learned of the Shi'a: The Institution of the Marja Taqlid. USA: Oxford University Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-19-513799-6.

- "The Super Genius Personality of Islam". Archived from the original on October 5, 2016. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- This has been translated into English twice: by Roy Mottahedeh as Lessons in Islamic Jurisprudence (2005) ISBN 978-1-85168-393-2 (Part 1 only) and anonymously as The Principles of Islamic Jurisprudence according to Shi'i Law (2003) ISBN 978-1-904063-12-4.

Sources

- Mallat, Chibli. "Muhammad Baqir as-Sadr." Pioneers of Islamic Revival. ed. Ali Rahnema. London: Zed Books, 1994