Hanafi

| Part of a series on |

| Sunni Islam |

|---|

|

|

|

The Hanafi school (Arabic: حَنَفِي, romanized: Ḥanafī) is one of the four principal Sunni schools of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh).[1] Its eponym is the 8th-century Kufan scholar Abū Ḥanīfa an-Nu‘man ibn Thābit, a tabi‘i of Persian origin whose legal views were preserved primarily by his two most important disciples, Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani.[2]

Under the patronage of the Abbasids, the Hanafi school flourished in Iraq and spread eastwards, firmly establishing itself in Khorasan and Transoxiana by the 9th-century, where it enjoyed the support of the local Samanid rulers.[3] Turkic expansion introduced the school to the Indian subcontinent and Anatolia, and it was adopted as the chief legal school of the Ottoman Empire.[4]

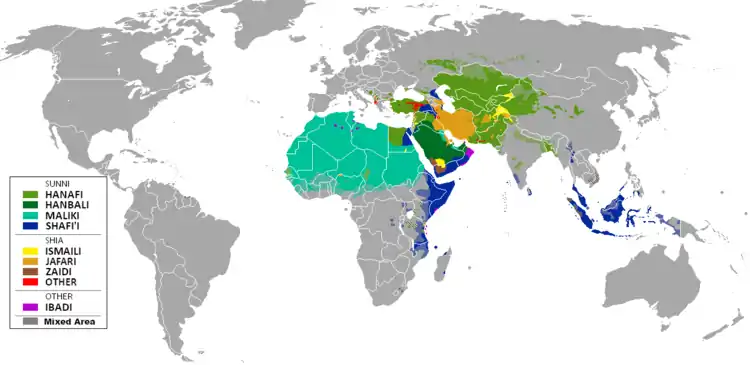

The Hanafi school is the maddhab with the largest number of adherents, followed by approximately one third of Muslims worldwide.[5][6] It is prevalent in Turkey, the Balkans, the Levant, Central Asia, the Indian subcontinent, Egypt and Afghanistan, in addition to parts of Russia, China and Iran.[7][8] The other primary Sunni legal schools are the Maliki, Shafi`i and Hanbali schools.[9][10]

Methodology

Hanafi usul recognises the Quran, hadith, consensus (ijma), legal analogy (qiyas), juristic preference (istihsan) and normative customs (urf) as sources of the Sharia.[2][11] Abu Hanifa is regarded by modern scholarship as the first to formally adopt and institute qiyas as a method to derive Islamic law when the Quran and hadith are silent or ambiguous in their guidance;[12] and is noted for his general reliance on personal opinion (ra'y).[2]

The foundational texts of Hanafi madhhab, credited to Abū Ḥanīfa and his students Abu Yusuf and Muhammad al-Shaybani, include Al-fiqh al-akbar (theological book on jurisprudence), Al-fiqh al-absat (general book on jurisprudence), Kitab al-athar (thousands of hadiths with commentary), Kitab al-kharaj and Kitab al-siyar (doctrine of war against unbelievers, distribution of spoils of war among Muslims, apostasy and taxation of dhimmi).[13][14][15]

Istihsan

The Hanafi school favours the use of istihsan, or juristic preference, a form of ra'y which enables jurists to opt for weaker positions if the results of qiyas lead to an undesirable outcome for the public interest (maslaha).[16] Although istihsan did not initially require a scriptural basis, criticism from other schools prompted Hanafi jurists to restrict its usage to cases where it was textually supported from the 9th-century onwards.[17]

History

As the fourth Caliph, Ali had transferred the Islamic capital to Kufa, and many of the first generation of Muslims had settled there, the Hanafi school of law based many of its rulings on the earliest Islamic traditions as transmitted by Sahaba residing in Iraq. Thus, the Hanafi school came to be known as the Kufan or Iraqi school in earlier times. Ali and Abdullah, son of Masud formed much of the base of the school, as well as other personalities such as Muhammad al-Baqir, Ja'far al-Sadiq, and Zayd ibn Ali. Many jurists and historians had lived in Kufa including one of Abu Hanifa's main teachers, Hammad ibn Sulayman.

The Sunni & 6th Shi'ite Imam Ja'far al-Sadiq (a descendant of the Islamic Nabi (Prophet) Muhammad) was reportedly a teacher of Sunni Imams Abu Hanifah and Malik ibn Anas, who in turn was a teacher of Imam Ash-Shafi‘i,[18][19]:121 who in turn was a teacher of Imam Ahmad ibn Hanbal. Thus all of the four great Imams of Sunni Fiqh are connected to Ja'far, whether directly or indirectly.[20]

In the early history of Islam, Hanafi doctrine was not fully compiled. The fiqh was fully compiled and documented in the 11th century.[21]

The Turkish rulers were some of the earliest adopters of the relatively more flexible Hanafi fiqh, and preferred it over the traditionalist Medina-based fiqhs which favored correlating all laws to Quran and Hadiths and disfavored Islamic law based on discretion of jurists.[22] The Abbasids patronized the Hanafi school from the 10th century onwards. The Seljuk Turkish dynasties of 11th and 12th centuries, followed by Ottomans adopted Hanafi fiqh. The Turkic expansion spread Hanafi fiqh through Central Asia and into Indian subcontinent, with the establishment of Seljuk Empire, Timurid dynasty, Khanates, Delhi Sultanate, Bengal Sultanate and Mughal Empire. Throughout the reign of Emperor Aurangzeb the Hanafi based Fatawa-e-Alamgiri served as the legal, juridical, political, and financial code of most of South Asia.[21][22]

References

- Ramadan, Hisham M. (2006). Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary. Rowman Altamira. pp. 24–29. ISBN 978-0-7591-0991-9.

- Warren, Christie S. "The Hanafi School". Oxford Bibliographies. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- Hallaq, Wael (2010). The Origins and Evolution of Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 173–174. ISBN 9780521005807.

- Hallaq, Wael (2009). An Introduction to Islamic Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 37. ISBN 978-0521678735.

- Jurisprudence and Law – Islam Reorienting the Veil, University of North Carolina (2009)

- "Hanafi School of Law - Oxford Islamic Studies Online". www.oxfordislamicstudies.com. Retrieved 2020-08-25.

- Siegbert Uhlig (2005), "Hanafism" in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha, Vol 2, Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, ISBN 978-3447052382, pp. 997–99

- Abu Umar Faruq Ahmad (2010), Theory and Practice of Modern Islamic Finance, ISBN 978-1599425177, pp. 77–78

- Gregory Mack, Jurisprudence, in Gerhard Böwering et al (2012), The Princeton Encyclopedia of Islamic Political Thought, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0691134840, p. 289

- "Sunnite". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2014.

- Hisham M. Ramadan (2006), Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 978-0759109919, p. 26

- See:

*Reuben Levy, Introduction to the Sociology of Islam, pp. 236–37. London: Williams and Norgate, 1931–1933.

*Chiragh Ali, The Proposed Political, Legal and Social Reforms. Taken from Modernist Islam 1840–1940: A Sourcebook, p. 280. Edited by Charles Kurzman. New York City: Oxford University Press, 2002.

*Mansoor Moaddel, Islamic Modernism, Nationalism, and Fundamentalism: Episode and Discourse, p. 32. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

*Keith Hodkinson, Muslim Family Law: A Sourcebook, p. 39. Beckenham: Croom Helm Ltd., Provident House, 1984.

*Understanding Islamic Law: From Classical to Contemporary, edited by Hisham Ramadan, p. 18. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

*Christopher Roederrer and Darrel Moellendorf, Jurisprudence, p. 471. Lansdowne: Juta and Company Ltd., 2007.

*Nicolas Aghnides, Islamic Theories of Finance, p. 69. New Jersey: Gorgias Press LLC, 2005.

*Kojiro Nakamura, "Ibn Mada's Criticism of Arab Grammarians." Orient, v. 10, pp. 89–113. 1974 - Oliver Leaman (2005), The Qur'an: An Encyclopedia, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0415326391, pp. 7–8

- Kitab Al-Athar of Imam Abu Hanifah, Translator: Abdussamad, Editors: Mufti 'Abdur Rahman Ibn Yusuf, Shaykh Muhammad Akram (Oxford Centre of Islamic Studies), ISBN 978-0954738013

- Majid Khadduri (1966), The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801869754

- "Istihsan". Oxford Islamic Studies Online. Retrieved 2020-08-26.

- Hallaq, Wael (2008). A History of Islamic Legal Theories: An Introduction to Sunnī Uṣūl al-Fiqh. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 978-0521599863.

- Dutton, Yasin, The Origins of Islamic Law: The Qurʼan, the Muwaṭṭaʼ and Madinan ʻAmal, p. 16

- Haddad, Gibril F. (2007). The Four Imams and Their Schools. London, the U.K.: Muslim Academic Trust. pp. 121–194.

- "Imam Ja'afar as Sadiq". History of Islam. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2012-11-27.

- Nazeer Ahmed, Islam in Global History, ISBN 978-0738859620, pp. 112–14

- John L. Esposito (1999), The Oxford History of Islam, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0195107999, pp. 112–14

Further reading

- Branon Wheeler, Applying the Canon in Islam: The Authorization and Maintenance of Interpretive Reasoning in Ḥanafī Scholarship (Albany, SUNY Press, 1996).

- Nurit Tsafrir, The History of an Islamic School of Law: The Early Spread of Hanafism (Harvard, Harvard Law School, 2004) (Harvard Series in Islamic Law, 3).

- Behnam Sadeghi (2013), The Logic of Law Making in Islam: Women and Prayer in the Legal Tradition, Cambridge University Press, Chapter 6, "The Historical Development of Hanafi Reasoning", ISBN 978-1107009097

- Theory of Hanafi law: Kitab Al-Athar of Imam Abu Hanifah, Translator: Abdussamad, Editors: Mufti 'Abdur Rahman Ibn Yusuf, Shaykh Muhammad Akram (Oxford Centre of Islamic Studies), ISBN 978-0954738013

- Hanafi theory of war and taxation: Majid Khadduri (1966), The Islamic Law of Nations: Shaybani's, Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 978-0801869754

- Burak, Guy (2015). The Second Formation of Islamic Law: The Ḥanafī School in the Early Modern Ottoman Empire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-09027-9.

External links

- Hanafiyya Bulend Shanay, Lancaster University

- Kitab al-siyar al-saghir (Summary version of the Hanafi doctrine of War) Muhammad al-Shaybani, Translator - Mahmood Ghazi

- The Legal Aspects of Marriage according to Hanafi Fiqh Islamic Quarterly London, 1985, vol. 29, no. 4, pp. 193–219

- Al-Hedaya, A 12th century compilation of Hanafi fiqh-based religious law, by Burhan al-Din al-Marghinani, Translated by Charles Hamilton

- Development of family law in Afghanistan: The role of the Hanafi Madhhab Central Asian Survey, Volume 16, Issue 3, 1997