Sherwani

Sherwani (Bengali: শেরওয়ানি; Hindi: शेरवानी; Urdu: شیروانی) is a long coat-like garment worn in the Indian subcontinent, very similar to a Western frock coat or a Polish and Lithuanian żupan. Originally associated with Muslim aristocracy during the period of British rule,[1] it is worn over a kurta with the combination of either a churidar, a dhoti, a pajama, or a shalwar/sirwal as the lower-body clothing. It can be distinguished from the achkan by the fact that it is shorter in length, is often made from heavier suiting fabrics, and by the presence of a lining. Sherwani is worn on formal occasions.

History

According to Emma Tarlo, the sherwani evolved from a Persian cape (balaba or chapkan), which was gradually given a more Indian form (angarkha), and finally developed into the sherwani, with buttons down the front, following European fashion.[2] It originated in the 19th century British India as the European style court dress of regional Mughal nobles and royals of northern India,[3] before being more generally adopted in the late 19th century. It appeared first at Lucknow in the 1820s.[4] It was gradually adopted by rest of the royalty and aristocracy of Subcontinent, and later by the general population, as a more evolved form of occasional traditional attire. The name of attire is possibly derived from Shirvan or Sherwan, a region of present-day Azerbaijan due to the folk dress of that area (Chokha) which resembles Sherwani in its outlook. Therefore, the garment may also be an Indianized derivative of the Caucasian dress due to ethnic and cultural linkages of Indo-Persian during Middle Ages.

Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, the sherwani is worn by people on formal occasions such as weddings and Eid.

India

In India, the achkan sherwani is generally worn for formal occasions in winter, especially by those from Rajasthan, Punjab, Delhi, Jammu, Uttar Pradesh and Hyderabad.[5][6] The achkan sherwani is generally associated with the Hindus while the simple sherwani was historically favoured by Muslims.[7] The two garments have significant similarities, though sherwanis typically are more flared at the hips and achkans are lengthier than simple sherwanis. The achkan later evolved into the Nehru Jacket, which is popular in India.[8] In India, the achkan or sherwani is generally worn with the combination of Churidar as the lower garment.[9]

Jawaharlal Nehru (left) wearing an achkan sherwani with churidar.[10]

Jawaharlal Nehru (left) wearing an achkan sherwani with churidar.[10] Achkan sherwani and churidar (lower body) worn by Arvind Singh Mewar and his kin during a Hindu wedding in Rajasthan, India.

Achkan sherwani and churidar (lower body) worn by Arvind Singh Mewar and his kin during a Hindu wedding in Rajasthan, India.

Pakistan

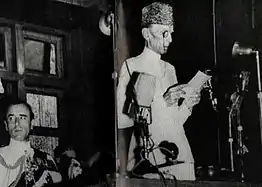

After the independence of Pakistan, Mohammad Ali Jinnah frequently wore the sherwani.[11] Following him, most people and government officials in Pakistan such as the President and Prime Minister started to wear the formal black sherwani over the shalwar qameez on state occasions and national holidays. General Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq made it compulsory for all officers to wear sherwani on state occasions and national holidays.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founder of Pakistan, is sitting on the Chair of Governor General, sometimes referred as Pakistan's Throne, wearing Sherwani.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah, founder of Pakistan, is sitting on the Chair of Governor General, sometimes referred as Pakistan's Throne, wearing Sherwani.

This is the image of supporters of Pakistan movement in which people can be seen wearing Sherwani, women can also be seen wearing a Female Sherwani.

This is the image of supporters of Pakistan movement in which people can be seen wearing Sherwani, women can also be seen wearing a Female Sherwani. Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right), founder of Pakistan, is standing with his sister Fatima Jinnah (left), Leading member of Pakistan Movement. Muhammad Ali Jinnah is wearing a Sherwani and Fatima Jinnah is also wearing a female Sherwani.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right), founder of Pakistan, is standing with his sister Fatima Jinnah (left), Leading member of Pakistan Movement. Muhammad Ali Jinnah is wearing a Sherwani and Fatima Jinnah is also wearing a female Sherwani. Muhammad Ali Jinnah (left), founder of Pakistan, is standing with his sister Fatima Jinnah (centre), Leading member of Pakistan Movement and Mumtaz Shahnawaz (right), another Leading member of Pakistan Movement and a Pakistani Diplomat. All of them are wearing Sherwani.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (left), founder of Pakistan, is standing with his sister Fatima Jinnah (centre), Leading member of Pakistan Movement and Mumtaz Shahnawaz (right), another Leading member of Pakistan Movement and a Pakistani Diplomat. All of them are wearing Sherwani. Fatima Jinnah (centre), Leading member of Pakistan Movement, is wearing a non-traditional and stylish Female Sherwani with Fur design on it.

Fatima Jinnah (centre), Leading member of Pakistan Movement, is wearing a non-traditional and stylish Female Sherwani with Fur design on it. Muhammad Ali Jinnah (left), founder of Pakistan, is sitting with Liaqat Ali Khan (centre), leading founding member of Pakistan and Hafeez Jalandhri (right), Leading member of Pakistan Movement and writer of National Anthem of Pakistan. All of them are wearing Sherwani.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (left), founder of Pakistan, is sitting with Liaqat Ali Khan (centre), leading founding member of Pakistan and Hafeez Jalandhri (right), Leading member of Pakistan Movement and writer of National Anthem of Pakistan. All of them are wearing Sherwani. Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right), founder of Pakistan, is standing with his sister Fatima Jinnah (left), Leading member of Pakistan Movement. Muhammad Ali Jinnah is wearing a Sherwani and Fatima Jinnah is also wearing a female Sherwani.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah (right), founder of Pakistan, is standing with his sister Fatima Jinnah (left), Leading member of Pakistan Movement. Muhammad Ali Jinnah is wearing a Sherwani and Fatima Jinnah is also wearing a female Sherwani.

Sri Lanka

In Sri Lanka, it was generally worn as the formal uniform of Mudaliyars and early Tamil legislators during the British colonial period.

Modern sherwanis

Sherwanis are mostly worn in Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.[12] These garments usually feature detailed embroidery or patterns. One major difference between sherwani wearing habits is the choice of lower garment, while in India, the dress is distinguished by their preference for churidars or pyjamas, in Pakistan and Bangladesh, it is mainly worn with shalwar instead.

Sherwanis have also been designed by the Indian designer, Rohit Bal for British Airways cabin crews serving on flights to India. Music director A.R. Rahman also appeared in a black sherwani to receive an Academy Award.

Pakistani journalist, filmmaker and activist, Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy appeared in sherwani to receive Academy Award in 2012 and 2015.[13][14][15][16][17]

Notes

- Condra, Jill (9 April 2013). Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing around the World [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313376375.

- Tarlo, Emma (1996). Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India. Hurst. ISBN 9781850651765.

- Jhala, Angma Dey (6 October 2015). Royal Patronage, Power and Aesthetics in Princely India. ISBN 9781317316572.

- The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. Cambridge University Press. 29 January 1988. ISBN 9781107392977.

- "Nehru's style statement".

- "Shifting Sands: Costume in Rajasthan".

- "From Cool to Un-cool to Re-cool: Nehru and Mao tunics in the sixties and post-sixties West".

- "Nehru's style statement".

- Altogether book. ISBN 9789325979710.

- "Nehru's style statement".

- Ahmed, Akbar S. (1997). Jinnah, Pakistan and Islamic Identity: The Search for Saladin. Psychology Press. pp. 99–. ISBN 978-0-415-14966-2.

- Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing Around the World [Volume 1], p. 571

- "Pakistan's Oscar triumph for acid attack film Saving Face". BBC News. Nosheen Abbas. Retrieved 28 December 2014.

- Oscar-winning Pakistani Filmmaker Inspired by Canada http://www.cbc.ca/news/arts/story/2012/02/28/oscar-saving-face-obaid-chinoy.html

- Clark, Alex (14 February 2016). "The case of Saba Qaiser and the film-maker determined to put an end to 'honour' killings". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

- Dawn 24 January 2012. Retrieved 24 January 2011

- "Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy fights to end honour killings with her film A Girl in the River". www.cbc.ca. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sherwani. |