Ethan Allen

Ethan Allen (January 21, 1738 [O.S. January 10, 1737][4] – February 12, 1789) was a farmer, businessman, land speculator, philosopher, writer, lay theologian, American Revolutionary War patriot, and politician. He is best known as one of the founders of Vermont and for the capture of Fort Ticonderoga early in the Revolutionary War. He was the brother of Ira Allen and the father of Frances Allen.

Ethan Allen | |

|---|---|

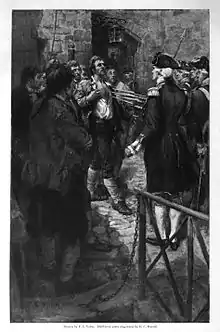

An engraving depicting Ethan Allen demanding the surrender of Fort Ticonderoga | |

| Born | January 10, 1737 Litchfield, Connecticut Colony |

| Died | February 12, 1789 (aged 52) Burlington, Vermont Republic |

| Buried | Greenmount Cemetery, Burlington |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1757 Connecticut provincial militia 1770–1775 Green Mountain Boys[1] |

| Rank | Major General (Vermont Republic militia) Colonel (Continental Army) |

| Commands held | Green Mountain Boys Fort Ticonderoga |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

| Other work | farmer, politician, land speculator, philosopher |

Allen was born in rural Connecticut and had a frontier upbringing, but he also received an education that included some philosophical teachings. In the late 1760s, he became interested in the New Hampshire Grants, buying land there and becoming embroiled in the legal disputes surrounding the territory. Legal setbacks led to the formation of the Green Mountain Boys, whom Allen led in a campaign of intimidation and property destruction to drive New York settlers from the Grants. He and the Green Mountain Boys seized the initiative early in the Revolutionary War and captured Fort Ticonderoga in May 1775. In September 1775, Allen led a failed attempt on Montreal which resulted in his capture by British authorities. He was imprisoned aboard Royal Navy ships, then paroled in New York City, and finally released in a prisoner exchange in 1778.

Upon his release, Allen returned to the New Hampshire Grants which had declared independence in 1777, and he resumed political activity in the territory, continuing resistance to New York's attempts to assert control over the territory. Allen lobbied Congress for Vermont's official state recognition, and he participated in controversial negotiations with the British over the possibility of Vermont becoming a separate British province.

Allen wrote accounts of his exploits in the war that were widely read in the 19th century, as well as philosophical treatises and documents relating to the politics of Vermont's formation. His business dealings included successful farming operations, one of Connecticut's early iron works, and land speculation in the Vermont territory. Allen and his brothers purchased tracts of land that became Burlington, Vermont. He was married twice, fathering eight children.

Early life

Allen was born in Litchfield, Connecticut Colony, the first child of Joseph and Mary Baker Allen, both descended from English Puritans.[5] The family moved to the town of Cornwall shortly after his birth due to his father's quest for freedom of religion during the Great Awakening.[6] As a boy, Allen already excelled at quoting the Bible and was known for disputing the meaning of passages.[7] He had five brothers (Heman, Heber, Levi, Zimri, and Ira) and two sisters (Lydia and Lucy). His brothers Ira and Heman were also prominent figures in the early history of Vermont.[8]

The town of Cornwall was frontier territory in the 1740s, but it began to resemble a town by the time that Allen was a teenager, with wood-frame houses beginning to replace the rough cabins of the early settlers. Joseph Allen was one of the wealthier landowners in the area by the time of his death in 1755. He ran a successful farm and had served as town selectman.[9] Allen began studies under a minister in the nearby town of Salisbury with the goal of gaining admission to Yale College.[10]

First marriage and early adulthood

Allen was forced to end his studies upon his father's death. He volunteered for militia service in 1757 in response to the French siege of Fort William Henry, but his unit received word that the fort had fallen while they were en route, and they turned back.[11] The French and Indian War continued over the next several years, but Allen did not participate in any further military activities and is presumed to have tended his farm. In 1762, he became part owner of an iron furnace in Salisbury.[12] He also married Mary Brownson from Roxbury in July 1762, who was five years his senior. They first settled in Cornwall, but moved the following year to Salisbury with their infant daughter Loraine. They bought a small farm and proceeded to develop the iron works.[13] The expansion of the iron works was apparently costly to Allen; he was forced to sell off portions of the Cornwall property to raise funds, and eventually sold half of his interest in the works to his brother Heman.[14] The Allen brothers sold their interest in the iron works in October 1765.[15]

By most accounts, Allen's first marriage was unhappy. His wife was rigidly religious, prone to criticizing him, and barely able to read and write. In contrast, his behavior was sometimes quite flamboyant, and he maintained an interest in learning.[16] Nevertheless, they remained together until Mary's death in 1783. They had five children together, only two of whom reached adulthood.[17]

Allen and his brother Heman went to the farm of a neighbor whose pigs had escaped onto their land, and they seized the pigs. The neighbor sued to have the animals returned to him; Allen pleaded his own case and lost. Allen and Heman were fined ten shillings, and the neighbor was awarded another five shillings in damages.[18] He was also called to court in Salisbury for inoculating himself against smallpox, a procedure that required the sanction of the town selectmen.[19]

Allen met Thomas Young when he moved to Salisbury, a doctor living and practicing just across the provincial boundary in New York. Young taught him a great deal about philosophy and political theory, while Allen shared his appreciation of nature and life on the frontier with Young. They eventually decided to collaborate on a book intended as an attack on organized religion, as Young had convinced Allen to become a Deist. They worked on the manuscript until 1764, when Young moved away from the area taking the manuscript with him.[20] Allen recovered the manuscript many years later, after Young's death. He expanded and reworked the material, and eventually published it as Reason: the Only Oracle of Man.[21]

Heman remained in Salisbury where he ran a general store until his death in 1778, but Allen's movements are poorly documented over the next few years.[22] He lived in Northampton, Massachusetts in the spring of 1766, where his son Joseph was born and where he invested in a lead mine.[23] The authorities asked him to leave Northampton in July 1767, though no official reason is known. Biographer Michael Bellesiles suggests that religious differences and Allen's tendency to be disruptive may have played a role in his departure.[24] Allen briefly returned to Salisbury before settling in Sheffield, Massachusetts with his younger brother Zimri. It is likely that his first visits to the New Hampshire Grants occurred during these years. Sheffield was the family home for ten years, although Allen was often absent for extended periods.[25]

New Hampshire Grants

New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth was selling land grants west of the Connecticut River as early as 1749, an area to which New Hampshire had always laid claim. Many of these grants were sold at relatively low prices to land speculators, who made land kick-backs to Wentworth. In 1764, King George issued an order resolving the competing claims of New York and New Hampshire in favor of New York.[26] New York had issued land grants that overlapped some of those sold by Wentworth, and authorities there insisted that holders of the Wentworth grants pay a fee to New York to have their grants validated. This fee approached the original purchase price, and many of the holders were land-rich and cash-poor, so there was a great deal of resistance to the demand. By 1769, the situation had deteriorated to the point that surveyors and other figures of New York authority were being physically threatened and driven from the area.[27]

A few of the holders of Wentworth grants were from northwestern Connecticut, and some of them were related to Allen, including Remember Baker and Seth Warner. In 1770, a group of them asked him to defend their case before New York's Supreme Court.[25] Allen hired Jared Ingersoll to represent the grant-holder interest in the trial, which began in July 1770 and pitted Allen against politically powerful New York grant-holders, including New York's Lieutenant Governor Colden, James Duane who was prosecuting the case, and Robert Livingston, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court who was presiding over the case. The trial was brief and the outcome unsurprising, as the court refused to allow the introduction of Wentworth's grants as evidence, citing their fraudulently issued nature.[28] Duane visited Allen and offered him payments "for going among the people to quiet them".[29] Allen denied taking any money[29] and claimed that Duane was outraged and left with veiled threats, indicating that attempts to enforce the judgment would be met with resistance.[30]

Many historians believe that Allen took these actions because he already held Wentworth grants of his own, although there is no evidence that he was issued any such grants until after he had been asked to take up the defense at the trial. He acquired grants from Wentworth to about 1,000 acres (400 ha) in Poultney and Castleton prior to the trial.[31]

Green Mountain Boys

On Allen's return to Bennington, the settlers met at the Catamount Tavern to discuss their options. These discussions resulted in the formation of the Green Mountain Boys in 1770, with local militia companies in each of the surrounding towns. Allen was named their Colonel Commandant, and cousins Seth Warner and Remember Baker were captains of two of the companies.[32] Further meetings resulted in creating committees of safety; they also laid down rules to resist New York's attempts to establish its authority. These included not allowing New York's surveyors to survey any land in the Grants, not just land owned through the Wentworth grants.[33] Allen participated in some of the actions to drive away surveyors, and he also spent much time exploring the territory. He sold some of his Connecticut properties and began buying land farther north in the territory, which he sold at a profit as the southern settlements grew and people began to move farther north.[34]

Friction increased with the provincial government in October 1771, when Allen and a company of Green Mountain Boys drove off a group of Scottish settlers near Rupert. Allen detained two of the settlers and forced them to watch them burn their newly constructed cabins. Allen then ordered them to "go your way now, and complain to that damned scoundrel your Governor, God damn your Governor, Laws, King, Council, and Assembly".[35] The settlers protested his language but Allen continued the tirade, threatening to send any troops from New York to Hell. In response, New York Governor William Tryon issued warrants for the arrests of those responsible, and eventually put a price of £20 (around £3.3k today) on the heads of six participants, including Allen.[35] Allen and his comrades countered by issuing offers of their own.

Ethan Allen, Remember Baker, Robert Cochran[36]

The situation deteriorated further over the next few years. Governor Tryon and the Green Mountain Boys exchanged threats, truce offers, and other writings, frequently written by Allen in florid and didactic language while the Green Mountain Boys continued to drive away surveyors and incoming tenants. Most of these incidents did not involve bloodshed, although individuals were at times manhandled, and the Green Mountain Boys sometimes did extensive property damage when driving tenants out. By March 1774, the harsh treatment of settlers and their property prompted Tryon to increase some of the rewards to £100.[37]

Onion River Company

Allen joined his cousin Remember Baker and his brother Ira, Heman, and Zimri to form the Onion River Company in 1772, a land-speculation organization devoted to purchasing land around the Winooski River, which was known then as the Onion River. The success of this business depended on the defense of the Wentworth grants. Early purchases included about 40,000 acres (16,000 ha) from Edward Burling and his partners; they sold land at a profit to Thomas Chittenden, among others, and their land became the city of Burlington.[38]

The outrage of the Wentworth proprietors was renewed in 1774 when Governor Tryon passed a law containing harsh provisions clearly targeted at the actions of the "Bennington Mob".[39][40] Vermont historian Samuel Williams called it "an act which for its savage barbarity is probably without parallel in the legislation of any civilized country".[39] Its provisions included the death penalty for interfering with a magistrate, and outlawing meetings of more than three people "for unlawful purposes" in the Grants.[39] The Green Mountain Boys countered with rules of their own, forbidding anyone in the Grants from holding "any office of honor or profit under the colony of N. York".[41]

Allen spent much of the summer of 1774 writing A Brief Narrative of the Proceedings of the Government of New York Relative to Their Obtaining the Jurisdiction of that Large District of Land to the Westward of the Connecticut River, a 200-page polemic arguing the position of the Wentworth proprietors.[42] He had it printed in Connecticut and began selling and giving away copies in early 1775. Historian Charles Jellison describes it as "rebellion in print".[43]

Westminster massacre

Allen traveled into the northern parts of the Grants early in 1775 for solitude and to hunt for game and land opportunities.[44] A few days after his return, news came that blood had finally been shed over the land disputes. Most of the resistance activity had taken place on the west side of the Green Mountains until then, but a small riot broke out in Westminster on March 13 and led to the deaths of two men.[45] Allen and a troop of Green Mountain Boys traveled to Westminster where the town's convention adopted a resolution to draft a plea to the King to remove them "out of so oppressive a jurisdiction".[46] It was assigned to a committee which included Allen.[47] The American Revolutionary War began less than a week after the Westminster convention ended, while Allen and the committee worked on their petition.[48]

Revolutionary War

Capture of Fort Ticonderoga

Allen received a message from members of an irregular Connecticut militia in late April, following the battles of Lexington and Concord, that they were planning to capture Fort Ticonderoga and requesting his assistance in the effort.[49] Allen agreed to help and began rounding up the Green Mountain Boys,[50] and 60 men from Massachusetts and Connecticut met with Allen in Bennington on 2 May, where they discussed the logistics of the expedition.[49] By 7 May, these men joined Allen and 130 Green Mountain Boys at Castleton. They elected Allen to lead the expedition, and they planned a dawn raid for May 10.[51] Two small companies were detached to procure boats, and Allen took the main contingent north to Hand's Cove in Shoreham to prepare for the crossing.[52]

On the afternoon of 9 May, Benedict Arnold unexpectedly arrived, flourishing a commission from the Massachusetts Committee of Safety. He asserted his right to command the expedition, but the men refused to acknowledge his authority and insisted that they would follow only Allen's lead. Allen and Arnold reached an accommodation privately, the essence of which was that Arnold and Allen would both be at the front of the troops when they attacked the fort.[53]

The troops procured a few boats around 2 a.m. for the crossing, but only 83 men made it to the other side of the lake before Allen and Arnold decided to attack, concerned that dawn was approaching.[54] The small force marched on the fort in the early dawn, surprising the lone sentry, and Allen went directly to the fort commander's quarters, seeking to force his surrender. Lieutenant Jocelyn Feltham was awakened by the noise, and called to wake the fort's commander Captain William Delaplace.[55] He demanded to know by what authority the fort was being entered, and Allen said, "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!"[56] Delaplace finally emerged from his chambers and surrendered his sword,[56] and the rest of the fort's garrison surrendered without firing a shot.[57] The only casualty had been a British soldier who became concussed when Allen hit him with a cutlass, hitting the man's hair comb and saving his life.[58]

Raids on St. John

On the following day, a detachment of the Boys under Seth Warner's command went to nearby Fort Crown Point and captured the small garrison there.[57] On 14 May, following the arrival of 100 men recruited by Arnold's captains, and the arrival of a schooner and some bateaux that had been taken at Skenesboro, Arnold and 50 of his men sailed north to raid Fort St. John, on the Richelieu River downstream from the lake, where a small British warship was reported by the prisoners to be anchored.[59][60] Arnold's raid was a success; he seized the sloop HMS Royal George, supplies, and a number of bateaux.[61]

Allen, shortly after Arnold's departure on the raid, decided, after his successes at the southern end of the lake, to take and hold Fort St. John himself. To that end, he and about 100 Boys climbed into four bateaux, and began rowing north.[62] After two days without significant food (which they had forgotten to provision in the boats), Allen's small fleet met Arnold's on its way back to Ticonderoga near the foot of the lake.[63] Arnold generously opened his stores to Allen's hungry men, and tried to dissuade Allen from his objective, noting that it was likely the alarm had been raised and troops were on their way to St. John. Allen, likely both stubborn in his determination, and envious of Arnold, persisted.[64]

When Allen and his men landed above St. John and scouted the situation, they learned that a column of 200 or more regulars was approaching. Rather than attempt an ambush on those troops, which significantly outnumbered his tired company, Allen withdrew to the other side of the river, where the men collapsed with exhaustion and slept without sentries through the night. They were awakened when British sentries discovered them and began firing grapeshot at them from across the river. The Boys, in a panic, piled into their bateaux and rowed with all speed upriver. When the expedition returned to Ticonderoga two days later, some of the men were greatly disappointed that they felt they had nothing to show for the effort and risks they took,[65] but the capture of Fort Ticonderoga and Crown Point proved to be important in the Revolutionary War because it secured protection from the British to the North and provided vital cannon for the colonial army.

Promoting an invasion

Following Allen's failed attempt on St. John, many of his men drifted away, presumably drawn by the needs of home and farm. Arnold then began asserting his authority over Allen for control of Ticonderoga and Crown Point. Allen publicly announced that he was stepping down as commander, but remained hopeful that the Second Continental Congress was going to name "a commander for this department ... Undoubtedly, we shall be rewarded according to our merit".[66] Congress, for its part, at first not really wanting any part of the affair, effectively voted to strip and then abandon the forts. Both Allen and Arnold protested these measures, pointing out that doing so would leave the northern border wide open.[67] They both also made proposals to Congress and other provincial bodies for carrying out an invasion of Quebec. Allen, in one instance, wrote that "I will lay my life on it, that with fifteen hundred men, and a proper artillery, I will take Montreal".[68] Allen also attempted correspondence with the people of Quebec and with the Indians living there in an attempt to sway their opinion toward the revolutionary cause.[69]

On June 22, Allen and Seth Warner appeared before Congress in Philadelphia, where they argued for the inclusion of the Green Mountain Boys in the Continental Army. After deliberation, Congress directed General Philip Schuyler, who had been appointed to lead the Army's Northern Department, to work with New York's provincial government to establish (and pay for) a regiment consisting of the Boys, and that they be paid Army rates for their service at Ticonderoga.[70] On July 4, Allen and Warner made their case to New York's Provincial Congress, which, despite the fact that the Royal Governor had placed a price on their heads, agreed to the formation of a regiment.[71] Following a brief visit to their families, they returned to Bennington to spread the news. Allen went to Ticonderoga to join Schuyler, while Warner and others raised the regiment.[72]

Allen loses command of the Boys

When the regimental companies in the Grants had been raised, they held a vote in Dorset to determine who would command the regiment. By a wide margin, Seth Warner was elected to lead the regiment. Brothers Ira and Heman were also given command positions, but Allen was not given any position at all in the regiment.[73] The thorough rejection stung; Allen wrote to Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull, "How the old men came to reject me I cannot conceive inasmuch as I saved them from the incroachments of New York."[74]

The rejection likely had several causes. The people of the Grants were tired of the disputes with New York, and they were tired of Allen's posturing and egotistic behavior, which the success at Ticonderoga had enhanced. Finally, the failure of the attempt on St. John's was widely seen as reckless and ill-advised, attributes they did not appreciate in a regimental leader.[75] Warner was viewed as a more stable and quieter choice, and was someone who also commanded respect. The history of Warner's later actions in the revolution (notably at Hubbardton and Bennington) may be seen as a confirmation of the choice made by the Dorset meeting.[76] In the end, Allen took the rejection in stride, and managed to convince Schuyler and Warner to permit him to accompany the regiment as a civilian scout.[74]

Capture

The American invasion of Quebec departed from Ticonderoga on August 28. On September 4, the army had occupied the Île aux Noix in the Richelieu River, a few miles above Fort St. John, which they then prepared to besiege.[77] On September 8, Schuyler sent Allen and Massachusetts Major John Brown, who had also been involved in the capture of Ticonderoga, into the countryside between St. John and Montreal to spread the word of their arrival to the habitants and the Indians.[78] They were successful enough in gaining support from the habitants that Quebec's governor, General Guy Carleton, reported that "they have injured us very much".[79]

When he returned from that expedition eight days later, Brigadier General Richard Montgomery had assumed command of the invasion due to Schuyler's illness. Montgomery, likely not wanting the troublemaker in his camp, again sent him out, this time to raise a regiment of French-speaking Canadiens. Accompanied by a small number of Americans, he again set out, traveling through the countryside to Sorel, before turning to follow the Saint Lawrence River up toward Montreal, recruiting upwards of 200 men.[80]

On September 24, he and Brown, whose company was guarding the road between St. John's and Montreal, met at Longueuil, and, according to Allen's account of the events, came up with a plan in which both he and Brown would lead their forces to attack Montreal. Allen and about 100 men crossed the Saint Lawrence that night, but Brown and his men, who were to cross the river at La Prairie, did not. General Carleton, alerted to Allen's presence, mustered every man he could, and, in the Battle of Longue-Pointe, scattered most of Allen's force, and captured him and about 30 men. His capture ended his participation in the revolution until 1778, as he was imprisoned by the British.[81] General Schuyler, upon learning of Allen's capture, wrote, "I am very apprehensive of disagreeable consequences arising from Mr. Allen's imprudence. I always dreaded his impatience and imprudence."[82]

Imprisonment

Much of what is known of Allen's captivity is known only from his own account of the time; where contemporary records are available, they tend to confirm those aspects of his story.[83]

Allen was first placed aboard HMS Gaspée, a brig anchored at Montreal. He was kept in solitary confinement and chains, and General Richard Prescott had, according to Allen, ordered him to be treated "with much severity".[84] In October 1775, the Gaspée went downriver, and her prisoners were transferred to the Adamant, which then sailed for England.[85] Allen wrote of the voyage that he "was put under the power of an English Merchant from London, whose name was Brook Watson: a man of malicious and cruel disposition".[86]

On arrival at Falmouth, England, after a crossing under filthy conditions, Allen and the other prisoners were imprisoned in Pendennis Castle, Cornwall. At first his treatment was poor, but Allen wrote a letter, ostensibly to the Continental Congress, describing his conditions and suggesting that Congress treat the prisoners it held the same way.[87] Unknown to Allen, British prisoners now included General Prescott, captured trying to escape from Montreal, and the letter came into the hands of the British cabinet. Also faced with opposition within the British establishment to the treatment of captives taken in North America, King George decreed that the men should be sent back to America and treated as prisoners of war.[88]

In January 1776, Allen and his men were put on board HMS Soledad, which sailed for Cork, Ireland. The people of Cork, when they learned that the famous Ethan Allen was in port, took up a collection to provide him and his men with clothing and other supplies.[89] Much of the following year was spent on prison ships off the American coast. At one point, while aboard HMS Mercury, she anchored off New York, where, among other visitors, the captain entertained William Tryon; Allen reports that Tryon glanced at him without any sign of recognition, although it is likely the New York governor knew who he was.[90] In August 1776, Allen and other prisoners were temporarily put ashore in Halifax, owing to extremely poor conditions aboard ship; due to food scarcity, both crew and prisoners were on short rations, and scurvy was rampant.[91] By the end of October, Allen was again off New York, where the British, having secured the city, moved the prisoners on-shore, and, as he was considered an officer, gave Allen limited parole.[92] With the financial assistance of his brother Ira, he lived comfortably, if out of action, until August 1777.[93] Allen then learned of the death of his young son Joseph due to smallpox.[94]

George Washington's impression of Allen[95]

According to another prisoner's account, Allen wandered off after learning of his son's death. He was arrested for violating his parole, and placed in solitary confinement.[96] There Allen remained while Vermont declared independence, and John Burgoyne's campaign for the Hudson River met a stumbling block near Bennington in August 1777. On 3 May, 1778, he was transferred to Staten Island.[97] Allen was admitted to General John Campbell's quarters, where he was invited to eat and drink with the general and several other British field officers. He stayed there for two days and was treated politely. On the third day Allen was exchanged for Colonel Archibald Campbell, who was conducted to the exchange by Colonel Elias Boudinot, the American commissary general of prisoners appointed by General George Washington. Following the exchange, Allen reported to Washington at Valley Forge. On 14 May, he was breveted a colonel in the Continental Army in "reward of his fortitude, firmness and zeal in the cause of his country, manifested during his long and cruel captivity, as well as on former occasions,"[93] and given military pay of $75 per month. The brevet rank, however, meant that there was no active role, until called, for Allen. Allen's services were never requested, and eventually the payments stopped.[2]

Vermont Republic

Return home

Following his visit to Valley Forge, Allen traveled to Salisbury, arriving on 25 May 1778. There he learned that his brother Heman had died just the previous week and that his brother Zimri, who had been caring for Allen's family and farm, had died in the spring following his capture. The death of Heman, with whom Allen had been quite close, hit him quite hard.[98]

Allen then set out for Bennington, where news of his impending return preceded him, and he was met with all of the honor due to a military war hero.[99] There he learned that the Vermont Republic had declared independence in 1777, that a constitution had been drawn up, and that election had been held.[100] Allen wrote of this homecoming that "we passed the flowing bowl, and rural felicity, sweetened with friendship, glowed in every countenance".[101] The next day he went to Arlington to see his family and his brother Ira, whose prominence in Vermont politics had risen considerably during Allen's captivity.[102]

Politics

Allen spent the next several years involved in Vermont's political and military matters. While his family remained in Arlington, he spent most of his time either in Bennington or on the road, where he could avoid his wife's nagging.[103] Shortly after his arrival, Vermont's Assembly passed the Banishment Act, a sweeping measure allowing for the confiscation and auction by the republic of property owned by known Tories. Allen was appointed to be one of the judges responsible for deciding whose property was subject to seizure under the law. (This law was so successful at collecting revenue that Vermont did not impose any taxes until 1781.)[104] Allen personally escorted some of those convicted under the law to Albany, where he turned them over to General John Stark for transportation to the British lines. Some of these supposed Tories protested to New York Governor George Clinton that they were actually dispossessed Yorkers. Clinton, who considered Vermont to still be a part of New York, did not want to honor the actions of the Vermont tribunals; Stark, who had custody of the men, disagreed with Clinton. Eventually the dispute made its way to George Washington, who essentially agreed with Stark since he desperately needed the general's services. The prisoners were eventually transported to West Point, where they remained in "easy imprisonment".[105]

While Allen's service as a judge in Vermont was brief, he continued to ferret out Tories and report them to local Boards of Confiscation for action. He was so zealous in these efforts that they also included naming his own brother Levi, who was apparently trying to swindle Allen and Ira out of land at the time. This action was somewhat surprising, as Levi had not only attempted to purchase Allen's release while he was in Halifax, but he had also traveled to New York while Allen was on parole there and furnished him with goods and money.[106] Allen and Levi engaged in a war of words, many of which were printed in the Connecticut Courant, even after Levi crossed British lines. They would eventually reconcile in 1783.[107]

Early in 1779, Governor Clinton issued a proclamation stating that the state of New York would honor the Wentworth grants, if the settlers would recognize New York's political jurisdiction over the Vermont territory. Allen wrote another pamphlet in response, entitled An Animadversory [sic] Address to the Inhabitants of the State of Vermont; with Remarks on a Proclamation under the Hand of his Excellency George Clinton, Esq; Governor of the State of New York. In typical style, Allen castigated the governor for issuing "romantic proclamations ... calculated to deceive woods people", and for his "folly and stupidity".[108] Clinton's response, once he recovered his temper, was to issue another proclamation little different from the first. Allen's pamphlet circulated widely, including among members of Congress, and was successful in casting the Vermonters' case in a positive light.[109]

In 1779, Allen published the account of his time in captivity, A Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen's Captivity ... Containing His Voyages and Travels, With the most remarkable Occurrences respecting him and many other Continental Prisoners of Observations. Written by Himself and now published for the Information of the Curious in all Nations. First published as a serial by the Pennsylvania Packet, the book was an instant best-seller;[110] it is still available today. While largely accurate, it notably omits Benedict Arnold from the capture of Ticonderoga, and Seth Warner as the leader of the Green Mountain Boys.[111]

Negotiations with the British

Allen appeared before the Continental Congress as early as September 1778 on behalf of Vermont, seeking recognition as an independent state. He reported that due to Vermont's expansion to include border towns from New Hampshire, Congress was reluctant to grant independent statehood to Vermont.[112] Between 1780 and 1783, Allen participated, along with his brother Ira, Vermont Governor Thomas Chittenden, and others, in negotiations with Frederick Haldimand, the governor of Quebec, that were ostensibly about prisoner exchanges, but were really about establishing Vermont as a new British province and gaining military protection for its residents.[113] The negotiations, once details of them were published, were often described by opponents of Vermont statehood as treasonous,[114] but no such formal charges were ever laid against anyone involved.[113]

Later years

As the war had ended with the 1783 Treaty of Paris, and the United States, operating under the Articles of Confederation, resisted any significant action with respect to Vermont, Allen's historic role as an agitator became less important, and his public role in Vermont's affairs declined.[115] Vermont's government had also become more than a clique dominated by the Allen and Chittenden families due to the territory's rapid population growth.[116]

In 1782, Allen's brother Heber died at the relatively young age of 38. Allen's wife Mary died in June 1783 of consumption, to be followed several months later by their first-born daughter Loraine. While they had not always been close, and Allen's marriage had often been strained, Allen felt these losses deeply. A poem he wrote memorializing Mary was published in the Bennington Gazette.[117]

Publication of Reason

In these years, Allen recovered from Thomas Young's widow, who was living in Albany, the manuscript that he and Young had worked on in his youth and began to develop it into the work that was published in 1785 as Reason: the Only Oracle of Man. The work was a typical Allen polemic, but its target was religious, not political. Specifically targeted against Christianity, it was an unbridled attack against the Bible, established churches, and the powers of the priesthood. As a replacement for organized religion, he espoused a mixture of deism, Spinoza's naturalist views, and precursors of Transcendentalism, with man acting as a free agent within the natural world. While historians disagree over the exact authorship of the work, the writing contains clear indications of Allen's style.[118]

The book was a complete financial and critical failure. Allen's publisher had forced him to pay the publication costs up front, and only 200 of the 1,500 volumes printed were sold. (The rest were eventually destroyed by a fire at the publisher's house.) The theologically conservative future president of Yale, Timothy Dwight, opined that "the style was crude and vulgar, and the sentiments were coarser than the style. The arguments were flimsy and unmeaning, and the conclusions were fastened upon the premises by mere force."[119] Allen took the financial loss and the criticism in stride, observing that most of the critics were clergymen, whose livelihood he was attacking.[120]

Second marriage

Allen met his second wife, a young widow named Frances "Fanny" Montresor Brush Buchanan, early in 1784; and after a brief courtship, they wed on 16 February 1784. Fanny came from a notably Loyalist background (including Crean Brush, notorious for acts during the Siege of Boston, from whom she inherited land in Vermont), but they were both smitten, and the marriage was a happy one.[121] They had three children: Fanny (1784–1819),[122] Hannibal Montresor (1786–1813), and Ethan Alphonso (1789–1855).[123] Fanny had a settling effect on Allen; for the remainder of his years he did not embark on many great adventures.[124]

The notable exception to this was when land was claimed by the Connecticut-based owners of the Susquehanna Company, who had been granted titles to land claimed by Connecticut in the Wyoming Valley, in an area that is now Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania.[125] The area was also claimed by Pennsylvania, which refused to recognize the Connecticut titles. Allen, after being promised land, traveled to the area and began stirring up not just Pennsylvania authorities but also his long-time nemesis, Governor Clinton of New York, by proposing that a new state be carved out of the disputed area and several counties of New York.[126] The entire affair was more bluster than anything else, and was resolved amicably when Pennsylvania agreed to honor the Connecticut titles.[127]

Allen was also approached by Daniel Shays in 1786 for support in what became the Shays's Rebellion in western Massachusetts. He was unsupportive of the cause, in spite of Shays's offer to crown him "king of Massachusetts"; he felt that Shays was just trying to erase unpayable debts.[128]

In his later years, independent Vermont continued to experience rapid population growth, and Allen sold a great deal of his land, but also reinvested much the proceeds in more land. A lack of cash, complicated by Vermont's currency problems, placed a strain on Fanny's relatively free hand on spending, which was further exacerbated by the cost of publishing Reason, and of the construction of a new home near the mouth of the Onion River.[129] He was threatened with debtors' prison on at least one occasion, and was at times reduced to borrowing money and calling in old debts to make ends meet.[130][131]

Allen and his family moved to Burlington in 1787, which was no longer a small frontier settlement but a small town, and much more to Allen's liking than the larger community that Bennington had become. He frequented the tavern there, and began work on An Essay on the Universal Plenitude of Being, which he characterized as an appendix to Reason. This essay was less polemic than many of his earlier writings. Allen affirmed the perfection of God and His creation, and credited intuition as well as reason as a way to bring Man closer to the universe.[132] The work was not published until long after his death, and is primarily of interest to students of Transcendentalism, a movement the work foreshadows.[133]

Death

On 11 February 1789, Allen traveled to South Hero, Vermont with one of his workers to visit his cousin, Ebenezer Allen, and to collect a load of hay. After an evening spent with friends and acquaintances, he spent the night there and set out the next morning for home.[134] While accounts of the return journey are not entirely consistent, Allen apparently suffered an apoplectic fit en route and was unconscious by the time they returned home. Allen died at home several hours later, without ever regaining consciousness.[135][136] He was buried four days later in the Green Mount Cemetery in Burlington.[137] The funeral was attended by dignitaries from the Vermont government and by large numbers of common folk who turned out to pay respects to a man many considered their champion.[137]

Allen's death made nationwide headlines. The Bennington Gazette wrote of the local hero, "the patriotism and strong attachment which ever appeared uniform in the breast of this Great Man, was worth of his exalted character; the public have to lament the loss of a man who has rendered them great service".[138] Although most obituaries were positive, a number of clergymen expressed different sentiments. "Allen was an ignorant and profane Deist, who died with a mind replete with horror and despair" was the opinion of Newark, New Jersey's Reverend Uzal Ogden.[137] Yale's Timothy Dwight expressed satisfaction that the world no longer had to deal with a man of "peremptoriness and effrontery, rudeness and ribaldry".[137] It is not recorded what New York Governor Clinton's reaction was to the news.[137]

Family

Allen's widow Fanny gave birth to a son, Ethan Alphonso, on 24 October 1789. She eventually remarried. Allen's two youngest sons went on to graduate from West Point and serve in the United States Army. H.M. Allen was the 7th graduate, a member of the Class of 1804, and served until 1813. E.A. Allen was the 22nd graduate, a member of the Class of 1806, and served until 1821. His daughter Fanny achieved notice when she converted to Roman Catholicism and entered a convent.[139] Two of his grandsons were Henry Hitchcock, Attorney General of Alabama and Ethan Allen Hitchcock, served as a Union Army general in the American Civil War. Reportedly General Hitchcock strongly resembled his famous grandfather. Two of Henry Hitchcock's sons were Henry Hitchcock and Ethan Allan Hitchcock.

Ira Allen

Ira Allen Fanny Allen

Fanny Allen.jpg.webp) Alabama Attorney General Henry Hitchcock

Alabama Attorney General Henry Hitchcock Union General Ethan Allan Hitchcock

Union General Ethan Allan Hitchcock.jpg.webp) Henry Hitchcock

Henry Hitchcock Ethan Allan Hitchcock

Ethan Allan Hitchcock

Disappearance of his grave marker

Sometime in the early 1850s, the original plaque marking Allen's grave disappeared; its original text was preserved by early war historian Benson Lossing in the 1840s. The inscription read:[140]

Corporeal part

of

General Ethan Allen

rests beneath this stone

The 12th Day of Feb., 1789

Aged 50 years.

His spirit tried the mercies of his God,

in whom he alone believed and strongly trusted[141]

In 1858, the Vermont Legislature authorized the placement of a 42-foot (13 m) column of Vermont granite in the cemetery, with the following inscription:[142]

Born in Litchfield Ct 10th Jan AD 1737

Died in Burlington Vt 12th Feb AD 1789

and buried near the site of this monument

The exact location within the cemetery of his remains is unknown.[143] While there is a vault beneath the 1858 cenotaph, it contains a time capsule from the time of the monument's erection.[144] According to the official 1858 report on the Ethan Allen monument, the funeral of Ethan Allen had taken place within Green Mount Cemetery; however the reason his remains had not been found at his memorial plaque {tablet} was because "... by the fact that some twenty years since, the dead of the Allen family had been arranged in a square enclosed by stone posts and chains, by Herman Allen, the nephew of Ethan Allen, and this tablet, then lying upon a dilapidated wall of brick work, was reconstructed with cut stone work, and it is presumed that, as a matter of convenience in giving a regular form to the enclosure, was removed some feet from its original position ..."[145] It was thus apparent it was actually a cenotaph tomb reconstruction that Benson Lossing sketched and presumed to be the actual tomb of Ethan Allen in his 1850 "The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution".[146]

Likenesses

No likenesses of Allen made from life have been found, in spite of numerous attempts to locate them. Efforts by members of the Vermont Historical Society and other historical groups through the years have followed up on rumored likenesses, only to come up empty. Photographs of Allen's grandson, General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, are extant, and, Hitchcock's mother said that he bore a strong resemblance to her father.[147] The nearest potential images included one claimed to be by noted Revolutionary War era engraver Pierre Eugene du Simitiere that turned out to be a forgery, and a reference to a portrait possibly by Ralph Earl that has not been found (as of Stewart Holbrook's writing in 1940).[148] Alexander Graydon, with whom Allen was paroled during his captivity in New York, described him like this:

His figure was that of a robust, large-framed man, worn down by confinement and hard fare; but he was now recovering his flesh and spirits; and a suit of blue clothes, with a gold laced hat that had been presented to him by the gentlement of Cork, enabled him to make a very passable appearance for a rebel colonel ... I have seldom met with a man, possessing, in my opinion, a stronger mind, or whose mode of expression was more vehement and oratorical. Notwithstanding that Allen might have had something of the insubordinate, lawless frontier spirit in his composition ... he appeared to me to be a man of generosity and honor.[149]

Memorials

Allen's final home, on the Onion River (now called the Winooski River), is a part of the Ethan Allen Homestead and Museum. Situated in Burlington, Allen's homestead is open for viewing via guided tours.[150]

Two ships of the United States Navy were named USS Ethan Allen in his honor, as were two 19th-century fortifications: a Civil War fort in Arlington County, Virginia and a cavalry outpost in Colchester and Essex, Vermont. The Vermont Army National Guard's facility in Jericho, Vermont is called the Camp Ethan Allen Training Site. A statue of Allen represents Vermont in National Statuary Hall of the United States Capitol.[151] A city park in the Montreal borough of Mercier–Hochelaga-Maisonneuve commemorating his capture bears his name.[152]

The Spirit of Ethan Allen III is a tour boat operating on Lake Champlain.[153] Allen's name is the trademark of the furniture and housewares manufacturer, Ethan Allen Inc., which was founded in 1932 in Beecher Falls, Vermont.[154] The Ethan Allen Express, an Amtrak train line running from New York City to Rutland, Vermont, is also named after him.

The Ethan Allen School was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1988.[155]

Publications

Allen is known to have written the following publications:

- Allen, Ethan (1779). A Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen's Captivity. C. Goodrich. ISBN 0-665-43295-X. OCLC 3505817. The 1779 edition of Allen's Narrative.

- —— (1849). Ethan Allen's Narrative of the Capture of Ticonderoga: And of His Captivity and Treatment by the British. C. Goodrich and S.B. Nichols. ISBN 0-665-22135-5. OCLC 17008777. An 1849 edition of Allen's Narrative.

- —— (2000). Stephen Carl Arch. (ed.). A Narrative of Colonel Ethan Allen's Captivity. Copley Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-58390-009-3. A 2000 edition of Allen's Narrative available at Amazon in March 2009

- —— (1854). Reason, the Only Oracle of Man: Or, A Compendious System of Natural Religion. J.P. Mendum. ISBN 1-150-69759-8. OCLC 84441828.

- —— (1779). Vindication of the Opposition of Vermont to the Government of New York. Spooner. OCLC 78281878.

- —— (1774). A brief narrative of the proceedings of the government of New-York. Ebenezer Watson. OCLC 166868772.

- Dean, John Ward; Folsom, George; Shea, John Gilmary; Stiles, Henry Reed; Dawson, Henry Barton (1873). An Essay on the Universal Plenitude of Being. Henry B. Dawson. OCLC 2105702. The essay is reprinted in four sections in this bound edition of The Historical Magazine and Notes and Queries: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4

See also

Biography portal

Biography portal

Notes

- Jellison, pp. 39, 142

- Jellison, p. 179

- Jellison, pp. 225, 272

- Allen's date of birth is made confusing by calendrical differences caused by the conversion between the Julian and Gregorian calendars. The first change offsets the date by 11 days. The second is that, at the time of Allen's birth, the New Year began on March 25. As a result, while his birth is officially recorded as happening on January 10, 1737, conversions due to these changes make the date in the modern calendar January 21, 1738. Adjusting for the movement of the New Year to January changes the year to 1738; adjusting for the Gregorian calendar changes the date from January 10 to 21. See Jellison, p. 2 and Hall (1895), p. 5.

- Hall (1895), p. 11

- Randall (2011), pp. 59–60, 72–78, 89–89

- Randall (2011), pp. 85–86

- Jellison, p. 3

- Bellesiles, p. 8

- Jellison, p. 5

- Jellison, p. 7

- Hall (1895), pp. 12–13

- Jellison, pp. 8–9

- Jellison, p. 9

- Bellesiles, p. 22

- Jellison, p. 8

- Bellesiles, p. 241

- Jellison, pp. 10–11

- Jellison, p. 12

- Jellison, pp. 15–17

- Holbrook, pp. 194–195, 225

- Jellison, p. 30

- Randall, p. 157

- Bellesiles, p. 23

- Jellison, p. 31

- Bellesiles, pp. 28–32

- Jellison, pp. 20–26

- Hall (1895), pp. 26–27

- Jellison, p. 37

- Jellison, p. 38

- Bellesiles, pp. 33–34

- Hall (1895), p. 27

- Jellison, p. 50

- Jellison, pp. 56–57

- Holbrook, p. 50

- Jellison, p. 62

- Jellison, pp. 62–91

- Jellison, pp. 77–86

- Jellison, p. 92

- Nelson (1990), p. 108

- Jellison, p. 94

- Jellison, pp 94–95

- Jellison, p. 96

- Jellison, p. 97

- Holbrook, p. 85

- Jellison, pp. 99–100

- Holbrook, p. 86

- Bellesiles, p. 113

- Jellison, p. 109

- Bellesiles, p. 116

- Jellison, p. 110

- Jellison, p. 111

- Randall (1990), p. 90

- Jellison, p. 115

- Randall (1990), p. 95

- Randall (1990), p. 96

- Bellesiles, p. 118

- Randall (1990), p. 307

- Randall, p. 101

- Smith (1907), p. 155

- Smith (1907), p. 157

- Jellison, p. 130

- Randall (1990), p. 105

- Jellison, pp. 129–130

- Jellison, pp. 130–131

- Jellison, p. 132

- Bellesiles, p. 121

- Jellison, p. 134

- Jellison, pp. 135–137

- Bellesiles, p. 122

- Holbrook, p. 999

- Jellison, p. 141

- Smith (1907), p. 255

- Bellesiles, p. 144

- Jellison, p. 144

- Jellison, p. 145

- Smith (1907), pp. 322–324

- Lanctot (1967), p. 65

- Jellison, p. 151

- Bellesiles, p. 126

- Lanctot (1967), pp. 77–78

- Bellesiles, p. 127

- Jellison, p. 161

- Jellison, p. 160

- Holbrook, p. 115

- Hall (1895), p. 124

- Holbrook, pp. 116–117

- Jellison, pp. 162–164

- Jellison, p. 165

- Jellison, p. 167

- Holbrook, p. 122

- Jellison, p. 170

- Boatner, pp. 17–18

- Holbrook, p. 126

- Jellison, p. 178

- Bellesiles, p. 130

- Holbrook, p. 127

- Jellison, pp. 180–181

- Holbrook, p. 137

- Jellison, p. 181

- Jellison, p. 187

- Jellison, p. 188

- Jellison, p. 194

- Holbrook, p. 140

- Jellison, pp. 198–200

- Jellison, pp. 200–201

- Jellison, p. 203

- Jellison, p. 205

- Jellison, p. 206

- Holbrook, pp. 158–59

- Jellison, pp. 218–19

- Hemenway, p. 941

- Vermont Historical Society, pp. 83–330, covers much of these negotiations and their political consequences.

- Vermont Historical Society, p. 220

- Jellison, p. 301

- Jellison, p. 302

- Jellison, p. 303

- Jellison, pp. 305–08

- Jellison, p. 310

- Jellison, p. 311

- Jellison, pp. 314–315

- Goesbriand, p. 12

- Brown, p. 279

- Jellison, p. 315

- Bellesiles, p. 248

- Holbrook, pp. 217–219

- Bellesiles, p. 251

- Holbrook, p. 243

- Jellison, p. 320

- Holbrook, p. 221

- Jellison, p. 321

- Jellison, pp. 325–326

- Jellison, p. 327

- Hall (1895), p. 198

- Colonel Red Reeder. Bold Leaders of the American Revolution. Little, Brown and Company, Boston. p. 22.

- Jellison, p. 330

- Jellison, p. 331

- Holbrook, p. 253

- Holbrook, p. 258

- The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution: Or, Illustrations, by ..., Volume 1 p.161

- Holbrook, p. 259. Holbrook notes that the age is incorrect; Allen was actually 51.

- Holbrook, p. 259

- Jellison, p. 333

- Vermont Committee on Ethan Allen Monument, p. 5

- "Report of the committee under the act providing for the erection of a monument over the grave of Ethan Allen" .p.5 1858 by Vermont. Committee on Ethan Allen Monument; Pomeroy, John Norton, 1828–1885; Marsh, George Perkins, 1801–1882; Vermont. General Assembly. Senate

- Sketch of Allen tomb by Lossing .p.161 from The Pictorial Field-book of the Revolution: Or, Illustrations, by ..., Volume 1 by Benson John Lossing 1850 {Google Books online}

- Holbrook, p. 264

- Holbrook, pp. 262–263

- Jellison, p. 171

- Ethan Allen Homestead Museum

- "Ethan Allen statue". Architect's Office of the Capitol. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- "List of open spaces – Mercier-Hochelaga-Maisonneuve". City of Montreal. Archived from the original on October 29, 2007. Retrieved November 11, 2011.

- "Spirit of Ethan Allen III". VermontVacation.com. Vermont Department of Tourism and Marketing. Archived from the original on May 1, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- "Ethan Allen, Inc. Corporate History". Ethan Allen Inc. Archived from the original on July 25, 2010. Retrieved December 24, 2009.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

References

- Bellesiles, Michael A (1993). Revolutionary Outlaws: Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. ISBN 978-0-8139-1603-3. OCLC 32287980.

- Boatner, Mark M (1966). Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. New York: D. McKay. pp. 17–18. ISBN 0-8117-0578-1. OCLC 426061.

- Brown, Charles (1902). Ethan Allen: of Green mountain fame, a hero of the revolution. M. A. Donohue. ISBN 9780795003769. OCLC 4410200.

- De Goesbriand, Louis (1886). Catholic memoirs of Vermont and New Hampshire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University. OCLC 5210201.

- Hall, Henry (1895). Ethan Allen: The Robin Hood of Vermont. New York: D. Appleton and Company. ISBN 9780795003752. OCLC 2553977.

- Hemenway, Abby Maria (ed) (1871). Vermont Historical Gazetteer, Volume 2. Burlington, VT: self-published. OCLC 3851423.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Holbrook, Stewart H (1940). Ethan Allen. New York: The MacMillan Company. ISBN 0-395-24908-2. OCLC 975403.

- Jellison, Charles A (1969). Ethan Allen: Frontier Rebel. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press. ISBN 0-8156-2141-8. OCLC 28329.

- Lanctot, Gustave (1967). Canada and the American Revolution 1774–1783. Harvard University Press. OCLC 70781264.

- Nelson, Paul David (1990). William Tryon and the Course of Empire: a Life in British Imperial Service. Chapel Hill, NC: UNC Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-1917-3. OCLC 21079316.

- Smith, Justin Harvey (1907). Our Struggle for the Fourteenth Colony: Canada, and the American Revolution, Volume 1. G.P. Putnam's Sons. OCLC 259236.

- Randall, Willard Sterne (1990). Benedict Arnold: Patriot and Traitor. William Morrow. ISBN 1-55710-034-9. OCLC 21163135.

- Randall, Williard Sterne (2011). Ethan Allen: His Life and Times. W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-07665-3.

- Vermont Committee on Ethan Allen Monument (1858). Report of the Committee Under the Act Providing for the Erection of a Monument Over the Grave of Ethan Allen (1858). Montpelier: E. P. Walton. OCLC 7471852.

- Vermont Historical Society (1871). Collections of the Vermont Historical Society, Volume 2. Montpelier, VT: Vermont Historical Society. OCLC 19358021.

- "The Ethan Allen Homestead Museum". Ethan Allen Homestead Museum. Retrieved August 1, 2010.

Further reading

- Bellesiles, Michael A. Revolutionary Outlaws: Ethan Allen and the Struggle for Independence on the Early American Frontier (University of Virginia Press, 1993)

- Duffy, John J., and H. Nicholas Muller III. Inventing Ethan Allen (University Press of New England, 2014) 285 pp.

- Hoyt, Edwin P (1976). The Damndest Yankee: Ethan Allen & his Clan. Brattleboro, Vermont: The Stephen Greene Press. ISBN 978-0-8289-0259-5. OCLC 2047850.

- Jellison, Charles Albert. Ethan Allen: frontier rebel (Countryman Press, 1974), popular biography

- McWilliams, John. "The Faces of Ethan Allen: 1760–1860." New England Quarterly (1976): 257–282. JSTOR 364502.

- Pell, John (1929). Ethan Allen. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-8369-6919-1. OCLC 503659743. 331pp

- Rife, Clarence W. "Ethan Allen, an Interpretation." New England Quarterly (1929) 2#4 pp: 561–584. JSTOR 359168.

- Shapiro, Darline. "Ethan Allen: Philosopher-Theologian to a Generation of American Revolutionaries." William and Mary Quarterly: A Magazine of Early American History (1964): 236–255. JSTOR 1920387.

Primary sources

- Allen, Ira (1798). The Natural and Political History of the State of Vermont. Charles E. Tuttle Co. OCLC 8242197.

- Moore, Hugh (1834). Memoir of Col. Ethan Allen; Containing the Most Interesting Incidents Connected With His Private and Public Career. Plattsburg, N.Y: O. R. Cook. ISBN 0-665-43980-6. OCLC 1493606.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Ethan Allen |

- Works by Ethan Allen at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Ethan Allen at Internet Archive

- Essay on natural religion by Allen: Reason: The Only Oracle of Man, published 1784

- Statue of Ethan Allen in the United States Capitol

- Davis, Kenneth S. (October 1963). "In the name of the Great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!". American Heritage. 14. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved November 28, 2007.

- Mombert, J. I. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography.

- . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "2000 Years of Disbelief: Ethan Allen" by James A. Haught, in Daylight Atheism, March 30, 2020