Battle of Monmouth

The Battle of Monmouth (also known as the Battle of Monmouth Court House) was fought near Monmouth Court House (modern-day Freehold Township, New Jersey) on June 28, 1778, during the American Revolutionary War. It pitted the Continental Army, commanded by General George Washington, against the British Army in North America, commanded by General Sir Henry Clinton.

| Battle of Monmouth | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth by Emanuel Leutze | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 14,300 | 17,660[lower-alpha 1] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

370 (official) c.500 (estimated) |

358 (official) Up to 1,134 (estimated) | ||||||

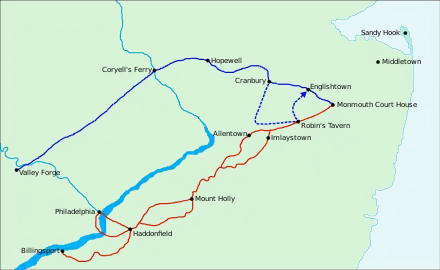

It was the last battle of the Philadelphia campaign, begun the previous year, during which the British had inflicted two major defeats on Washington and occupied Philadelphia. Washington had spent the winter at Valley Forge rebuilding his army and defending his position against political enemies who favored his replacement as commander-in-chief. In February 1778, the French-American Treaty of Alliance tilted the strategic balance in favor of the Americans, forcing the British to abandon hopes of a military victory and adopt a defensive strategy. Clinton was ordered to evacuate Philadelphia and consolidate his army. The Continental Army shadowed the British as they marched across New Jersey to Sandy Hook, from where the Royal Navy would ferry them to New York. Washington's senior officers urged varying degrees of caution, but it was politically important for him not to allow the British to withdraw unscathed. Washington detached around a third of his army and sent it ahead under the command of Major General Charles Lee, hoping to land a heavy blow on the British without becoming embroiled in a major engagement.

The battle began badly for the Americans when Lee botched an attack on the British rearguard at Monmouth Court House. A counter-attack by the main British column forced Lee to retreat until Washington arrived with the main body. Clinton disengaged when he found Washington in an unassailable defensive position and resumed the march to Sandy Hook.

Clinton had divided his army into two divisions for the march from Philadelphia; most of the combat troops were concentrated in the first division, while the second comprised most of the heavy transport of a 1,500-wagon baggage train. The British were harassed by increasingly strong American forces as they traversed New Jersey, and by June 27, Lee's vanguard was within striking distance. When the British left Monmouth Court House the next day, Lee attempted to isolate and defeat their rearguard. The attack was poorly coordinated, and the Americans were quickly outnumbered when the British first division returned. Some of Lee's units began to withdraw, leading to a breakdown in command and control and forcing Lee to order a general retreat. A fiercely fought rearguard action by the vanguard gave Washington enough time to deploy the main body in a strong defensive position, against which British efforts to press the vanguard foundered. The infantry battle gave way to a two-hour artillery duel, during which Clinton began to disengage. The duel ended when a Continental brigade established artillery on a hill overlooking the British lines, forcing Clinton to withdraw his guns. Washington launched two small-unit attacks on Clinton's infantry as they withdrew, inflicting heavy casualties on the British during the second. An attempt by Washington to probe the British flanks was halted by sunset, and the two armies settled down within one mile (two kilometers) of each other. The British slipped away unnoticed during the night to link up with the baggage train. The rest of the march to Sandy Hook was completed without further incident, and Clinton's army was ferried to New York in early July.

The battle was tactically inconclusive and strategically irrelevant; neither side landed the blow they hoped to on the other, Washington's army remained an effective force in the field, and the British redeployed successfully to New York. Both sides sustained considerable casualties, though the majority were from heat-related illness and exhaustion rather than combat. The Continental Army is estimated to have inflicted more losses than it received, and it was one of the rare occasions on which it retained possession of a battlefield. It had proven itself to be much improved after the training it underwent over the winter, and the professional conduct of the American troops during the battle was widely noted by the British. Washington was able to present the battle as a triumph, and he was voted a formal thanks by Congress to honor "the important victory of Monmouth over the British grand army." His position as commander-in-chief became unassailable. He was lauded for the first time as the Father of his Country, and his detractors were silenced. Lee was vilified for his failure to press home the attack on the British rearguard. Because of his tactless efforts to argue his case in the days after the battle, Washington had him arrested and court-martialed on charges of disobeying orders, conducting an "unnecessary, disorderly, and shameful retreat" and disrespect towards the commander-in-chief. Lee made the fatal mistake of turning the proceedings into a contest between himself and Washington. He was found guilty on all counts, although his culpability on the first two charges was debatable.

Today, the site of the battle is a New Jersey State Park which preserves the land for the public, called Monmouth Battlefield State Park.

Background

In 1777, some two years into the American Revolutionary War, the British commander-in-chief General Sir William Howe launched the Philadelphia campaign to capture the rebels' capital and persuade them to sue for peace. In the fall of that year, Howe inflicted two significant defeats on General George Washington and his Continental Army, at Brandywine and Germantown, and occupied Philadelphia, forcing the Second Continental Congress to hurriedly decamp to York, Pennsylvania.[2][3] Washington avoided battle for the rest of the year, and in December he withdrew to winter quarters at Valley Forge, despite the desire of Congress that he continue campaigning.[4][5][6] In comparison, his subordinate General Horatio Gates had won major victories in September and October at the Battles of Saratoga.[7] Washington was criticized in some quarters within the army and Congress for relying on a Fabian strategy to wear the British down in a long war of attrition instead of defeating it decisively in a pitched battle.[8]

In November, Washington was hearing rumors of a "Strong Faction" within Congress that favored replacing him with Gates as commander-in-chief.[9] The congressional appointments of the known critic General Thomas Conway as Inspector General of the Army and of Gates to the Board of War and Ordnance in December convinced Washington there was a conspiracy to take command of the army from him.[10][lower-alpha 2] Over a winter in which supplies were scarce and deaths from disease accounted for 15 per cent of his force, he battled to keep both the army from dissolution and his position as its commander-in-chief.[12] He successfully waged a "clever campaign of political infighting"[13] in which he presented a public image of disinterest, a man without guile or ambition, while working through his allies in Congress and the army to silence his critics.[14][15] Nevertheless, the doubts about his leadership remained, and he needed success on the battefield if he was to be sure of his position.[15]

The British, meanwhile, had failed to eliminate the Continental Army and force a decisive end to the American rebellion, despite investing significant resources in North America to the detriment of defenses elsewhere in the empire.[16] In Europe, France was maneuvering to exploit the opportunity to weaken a long-term rival. Following the Franco-American alliance of February 1778, French forces were sent to North America to support the revolutionaries. This led to the Anglo-French War (1778–1783), which Spain would join on the French side in 1779. With the rest of Europe moving towards a hostile neutrality, Great Britain would come under further pressure in 1780 when the Dutch allied with France, leading to the Fourth Anglo-Dutch War. Faced with military escalation, increasing diplomatic isolation and limited resources, the British were forced to prioritize the defense of the homeland and more valuable colonial possessions in the Caribbean and India above their North American colonies. They abandoned their efforts to win a decisive military victory, repealed the Intolerable Acts which had precipitated the rebellion and, in April 1778, sent the Carlisle Peace Commission in an attempt to reach a negotiated settlement. In Philadelphia, the newly installed commander-in-chief General Sir Henry Clinton was ordered to redeploy 8,000 troops, a third of his army, to the West Indies and Florida, consolidate the rest of his army in New York and adopt a defensive posture.[17][18][19]

Continental Army

Washington's preference for a professional standing army rather than a militia had been another source of criticism.[20] He had seen his army dissolve in the fall of 1775 as short-term enlistments expired, and blamed his defeat in the Battle of Long Island in August 1776 in part on a poorly performing militia.[21] At his urging, Congress passed legislation between September and December 1776 to create an army in which troops would enlist for the duration. Recruitment failed to raise sufficient numbers, and the harsh discipline implemented by Washington, the long periods away from home and the defeats of 1777 further weakened the army through desertions and frequent officer resignations.

Although the army that went into Valley Forge contained the kernel of regimental organization and a core of experienced officers and men, no-one was under any illusion that it was a match for the tactical skill of the British Army.[22] The situation improved measurably with the arrival in March 1778 of Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben, to whom Washington gave the responsibility for training the army. With the commander-in-chief's enthusiastic support, Steuben implemented a uniform standard of drill where none had previously existed and worked the army hard, transforming it into a more professional force that might compete on equal terms with the British Army.[23][24][lower-alpha 3]

On May 21, Major General Charles Lee rejoined the Continental Army. Lee was a former British Army officer who had retired to Virginia before the revolution and had been touted as a potential commander of the army alongside Washington when war broke out. He had been captured in December 1776 following Washington's defeat at New York, and had been released in April in a prisoner exchange. He had been critical of Washington's indecisiveness at New York and insubordinate during the retreat from the city. But Washington had regarded him as his most trusted adviser and the best officer in the Continental Army, and he eagerly welcomed Lee back as his second-in-command.[25][26][27]

Sixteen months in captivity had not mellowed Lee. He remained respectful to Washington's face but continued to be critical about the commander-in-chief's abilities to others, and it is likely that Washington's friends reported this back to Washington.[28][29] Lee was dismissive of the Continental Army, denigrated Steuben's efforts to improve it and went over Washington's head to submit to Congress a plan to reorganize it on a militia basis, prompting Washington to reprove him.[30] Nevertheless, Lee was respected by many of Washington's officers and held in high esteem by Congress, and Washington gave him command of the division that would soon lead the Continental Army out of Valley Forge.[31][19]

Prelude

In April, before news of the French alliance reached him, Washington issued a memorandum to his generals seeking their opinions on three possible alternatives for the upcoming campaign: attack the British in Philadelphia, shift operations to New York or remain on the defensive at Valley Forge and continue to build up the army. Of the twelve responses, all agreed it was vital that, whatever course was chosen, the army had to perform well if public support for the revolution was to be maintained after the disappointments of the previous year. Most generals supported one or other of the offensive options, but Washington sided with the minority, among them Steuben, who argued the Continental Army still needed improvement at Valley Forge before it was ready to take on the British. After news of the Franco-American alliance arrived and as British activity in and around Philadelphia increased, Washington met with ten of his generals on May 8 to further discuss plans. This time they unanimously favored the defensive option and waiting until the British intentions became clearer.[32]

In May, it became evident that the British were preparing to evacuate Philadelphia, but Washington still had no detailed knowledge of Clinton's intentions and was concerned that the British would slip away overland through New Jersey. The 2nd New Jersey Regiment, which had been conducting operations against British foragers and sympathizers in New Jersey since March, was a valuable source of intelligence, and by the end of the month a British evacuation by land looked increasingly likely. Washington reinforced the regiment with the rest of the New Jersey Brigade, commanded by Brigadier General William Maxwell, with orders to obstruct and harry British activities.[33] The Continentals were to co-operate with the experienced New Jersey militia, commanded by Major General Philemon Dickinson, one of the most capable militia commanders of the war and Washington's single best source of intelligence on British activities.[34] On May 18, Washington sent the inexperienced, 20-year-old Major General Lafayette with 2,200 men to establish an observation post at Barren Hill, eleven miles (eighteen kilometers) from Philadelphia. The Frenchman's first significant independent command almost ended in disaster for him two days later in the Battle of Barren Hill, and only the discipline of his men prevented his entrapment by the British.[35]

March from Philadelphia

On June 15, the British began to withdraw from Philadelphia, crossing the River Delaware into New Jersey. The last troops crossed three days later, and the army consolidated around Haddonfield. Clinton, who had not yet decided on the exact route to New York approximately ninety miles (one hundred forty-five kilometers) away, divided his army into two divisions and set out for Allentown, some forty miles (sixty-four kilometers) to the northeast. He accompanied the first division, which comprised some 10,000 troops under the command of Lieutenant General Charles Lord Cornwallis. The second division, commanded by Lieutenant General Wilhelm von Knyphausen, comprised just over 9,000 personnel, of which over 7,500 were combatants. This division contained the bulk of the slow-moving heavy transport of the 1,500-wagon baggage train.[36]

The march was conducted in short segments during a heat wave in which temperatures frequently exceeded 90 °F (32 °C), which further slowed progress and caused casualties from heat exhaustion. The slow progress did not concern Clinton. He was confident his troops were more than a match for Washington's forces and felt that a major battle would compensate for the humiliation of having to abandon Philadelphia and might even deal a serious blow to the rebellion.[37][38] Wherever possible, the two divisions followed parallel routes which allowed them to be mutually supporting. Light troops and pioneers screened the route ahead of the main force and cleared obstacles, combat units were embedded with the baggage train and battalion-sized units provided flank guards.[39] The frequent sniping and skirmishing of Maxwell's Continentals and Dickinson's militia, and their attempts to obstruct and hinder the British by blocking roads, destroying bridges and spoiling wells, did not materially impede progress.[40][41]

On June 24, the first division arrived at Allentown while the second reached Imlaystown, four miles (six kilometers) to the east.[42] Clinton decided to head for Sandy Hook, from where the Royal Navy could ferry his army to New York. When the march resumed at 04:00 the next day, the road network made it impossible for the two divisions to follow separate routes and still remain within supporting distance of each other. Knyphausen's second division led the twelve-mile (nineteen-kilometer) column on the road towards Monmouth Court House (modern-day Freehold). Cornwallis followed, Guards and Grenadiers at the rear, putting his combat-heavy division between the baggage train and the likely direction of attack. At the end of the day, Knyphausen camped at Freehold Township, some four miles (six kilometers) from Monmouth Court House, while Clinton established his headquarters at Robin's Rising Sun Tavern, twelve miles (nineteen kilometers) from Knyphausen.[43][44]

The next day, June 26, the British suffered almost forty casualties in near-constant skirmishing in which one unit came close to being overrun. Knyphausen reached Monmouth Court House early that morning, and by 10:00 the entire column had concentrated there. It was clear to Clinton that Washington's forces were gathering in numbers, and the British were exhausted after their sixty-seven-mile (one-hundred-eight-kilometer) march from Philadelphia. Monmouth Court House offered a good defensive position, and it is possible that Clinton saw an opportunity for the battle he desired. He deployed his army to cover all approaches and decided to rest his troops for the next two nights. The bulk of his force, the first division, was deployed on the Allentown road, covering the second division in the village.[45]

The revolution had precipitated a vicious civil war in Monmouth County that did credit to neither side and which would continue after the armies had departed.[46] It was fought between Patriots, who sided with the rebellion, and Loyalists, who remained loyal to Great Britain and even formed units, such as the Queen's American Rangers, which fought alongside the British Army.[47] The two sides also fought each other in the civil arena, and it is estimated that fifty per cent of Monmouth County families suffered significant harm to person or property during the war.[48] By spring 1778, the formerly loyalist Monmouth Court House had come under patriot control.[49] When the British arrived, they found themselves in an enemy settlement that had been largely deserted by its inhabitants. Clinton's orders against pillaging were ignored by the rank and file and went unenforced by the officers. British and Hessian soldiers acting out of frustration and anger, and Loyalists acting out of rage and vengeance, committed numerous acts of vandalism, looting and arson. By the time Clinton resumed the march on June 28, thirteen of the village's near two dozen buildings had been destroyed, all of them Patriot owned.[50]

Pursuit

Washington learned the British were evacuating Philadelphia on June 17. He immediately convened a war council, at which all but two of seventeen generals believed the Continental Army still could not win a pitched battle against the British, Lee arguing it would be criminal to attempt one. Unsure of Clinton's exact intentions and with his officers urging caution, Washington determined to pursue the British and move to within striking distance. Lee's brigades led the Continental Army out of Valley Forge on the afternoon of June 18, and four days later the last troops crossed the Delaware into New Jersey at Coryell's Ferry.[51][52] Washington divided his army into two wings commanded by Lee and Major General Lord Stirling and a reserve commanded by Lafayette. Traveling light, Washington reached Hopewell on June 23, less than twenty-five miles (forty kilometers) north of the British at Allentown. While the army set up camp, Colonel Daniel Morgan was ordered south with 600 light infantry to reinforce Maxwell and Dickinson.[53]

On June 24, Dickinson informed Washington the efforts he and Maxwell were making to slow Clinton were having little impact, and that he believed Clinton was deliberately lingering in New Jersey to provoke a battle.[54] Washington convened another war council in which the twelve officers who attended all recommended varying degrees of caution. Lee argued that a victory would be of little benefit while a defeat would do irrevocable damage to the revolutionary cause. He preferred not to risk the Continental Army against a professional, well-trained enemy until French intervention swayed the odds in the Americans' favor and proposed that Clinton should be allowed to proceed to New York unmolested. Four other generals agreed. Even the most aggressive of the remainder wanted to avoid a major engagement; Brigadier General Anthony Wayne suggested the dispatch of 2,500–3,000 additional troops to reinforce Maxwell and Dickinson that would enable them, with a third of the army, to make "an Impression in force." In the end, a compromise was agreed in which 1,500 picked men[lower-alpha 4] would reinforce the vanguard to "act as occasion may serve." To Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton, who attended as an aide, the council "would have done honor to the most honorab[le] society of midwives, and to them only." A disappointed Washington sent the token force under the command of Brigadier General Charles Scott.[56]

Soon after the council adjourned, Wayne – who had refused to put his name to the compromise – Lafayette and Major General Nathanael Greene contacted Washington individually with the same plea for a stronger vanguard action supported by the main body, while still avoiding a major battle. Lafayette assured Washington that Steuben and Brigadier General Louis Duportail agreed, and told Washington it "would be disgraceful for the leaders and humiliating for the troops to allow the enemy to cross the Jerseys with impunity." Greene emphasized the political aspect, advising Washington the public expected him to attack and that even if a limited attack did lead to a major battle, he thought their chances of success were good. It was all Washington, keen to erase the defeats of the previous year and prove his critics wrong, needed to hear. By the early hours of June 25 he had ordered Wayne to follow Scott with another 1,000 picked men. He wanted to do more than simply harass Clinton and, while still avoiding the risk of a major battle, hoped to inflict a heavy blow on the British, one that would surpass his success at the Battle of Trenton in 1776.[57][58]

Reining in Lafayette

Washington offered Lee command of the vanguard, but Lee declined, stating the force was too small for a man of his rank and position.[lower-alpha 5] Washington appointed Lafayette instead, with orders to attack "with the whole force of your command" if the opportunity presented itself. Lafayette failed to establish full control of the disparate forces under his command, and in his haste to catch the British, he pushed his troops to breaking point and outran his supplies. Washington grew increasingly concerned, and on the morning of June 26 he warned Lafayette not to "distress your men by an over hasty march." By that afternoon, Lafayette was at Robin's Tavern, where Clinton had stayed the previous night. He was within three miles of the British, too far away from the main army for it to support him, and his men were exhausted and hungry. He remained eager to fight and discussed with his officers a night march with the intention of striking Clinton the next morning.[61]

That evening, Washington ordered Lafayette to leave Morgan and the militia behind as a screen and move to Englishtown, where he would be back in range of both supplies and the main army.[62][lower-alpha 6] By this time Lee, having realized Lafayette's force was more significant than he first thought, had changed his mind and requested command of it. Washington ordered Lee to take Scott's former brigade and the brigade of Brigadier General James Varnum, link up with Lafayette in Englishtown and take command of all advance forces. Greene took over command of Lee's wing of the main body.[64][lower-alpha 7] By June 27, Lafayette was safely back in the fold with what was now Lee's vanguard of some 4,500 troops[lower-alpha 8] at Englishtown, six miles (ten kilometers) from the British at Monmouth Court House. Washington was with the main body of just over 7,800 troops and the bulk of the artillery at Manalapan Bridge, four miles (six kilometers) behind Lee.[68] Morgan's light infantry, now increased to 800 men by the addition of a militia detachment, was at Richmond Mills, a little over two miles (three kilometers) to the south of Monmouth Court House.[69][lower-alpha 9] Dickinson's 1,200 or more militia were on Clinton's flanks, with a significant concentration about two miles (three kilometers) west of Monmouth Court House.[71]

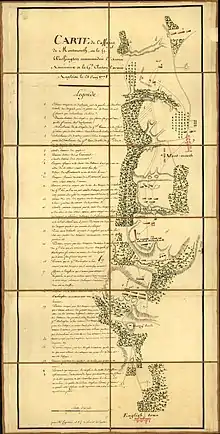

Battle

On the afternoon of June 27, Washington conferred with the vanguard's senior officers at Englishtown but did not offer a battle plan. Lee believed he had full discretion on whether and how to attack and called his own war council after Washington left. He intended to advance as soon as he knew Clinton was on the move, in the hope of catching the British rearguard when it was most vulnerable. In the absence of any intelligence about Clinton's intentions or the terrain, Lee believed it would be useless to form a precise plan of his own; he told his commanders only to be ready for action at short notice and follow his orders.[60][72] In response to a written order received from Washington in the early hours of June 28, Lee ordered Colonel William Grayson to take 700 men forward. They were to watch for any British move and, if one did occur, try and slow them to give the vanguard time to close the distance.[73]

Grayson did not depart Englishtown until 06:00, an hour after news arrived that Clinton was on the move.[74] Both vanguard and main body broke camp immediately, and both were slow to move; the vanguard was delayed when brigades formed up in the wrong march order and the main body was slowed by its artillery train.[75] At 07:00, Lee rode ahead to scout the situation for himself. Following some confusion when a militia rider erroneously reported the British were not withdrawing but preparing to attack, Lee learned that the British had begun moving at 02:00 and only a small party of infantry and cavalry remained in the area.[76]

Clinton's first move had been to deploy the Queen's Rangers northwest of Monmouth Court House to cover the departure of the second division, scheduled for an hour later but delayed until 04:00. By 05:00, the first division had begun moving, and the last British troops left Monmouth Court House by 09:15, heading northeast on the road to Middletown. Trailing the column was the rearguard, comprising a battalion of light infantry and a regiment of dragoons which, with the Rangers, totaled 1,550–2,000 troops.[77][78]

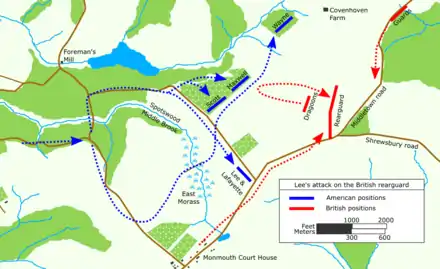

Advance to contact

The first shots were exchanged around 08:00 in an entirely American skirmish between a small detachment of Rangers and Dickinson's militia. Grayson arrived just in time to deploy his troops in support of the militia near a bridge over a ravine and watch the Rangers withdraw.[79][lower-alpha 10] The bridge was on the Englishtown–Monmouth Court House road and spanned the Spotswood Middle Brook, one of three ravines bordered by marshy wetlands or 'morasses' that cut through what would soon become a battlefield. Other than by bridge, the ravines were negotiable with difficulty by infantry and not at all by artillery; any unit cut off on the wrong side or pinned up against them would find itself in grave danger. When Lee caught up with Grayson shortly after the skirmish, Dickinson, who still believed the British occupied Monmouth Court House in force, strongly urged him not to venture across the brook. With intelligence about British activity still contradictory, Lee lost an hour at the bridge. He did not advance until Lafayette arrived with the rest of the vanguard.[81][82]

Once the vanguard was concentrated at the bridge, Lee replaced Grayson with Wayne to command the approximately 550-man lead element, which comprised detachments led by Colonel Richard Butler, Colonel Henry Jackson and Grayson (returned to the command of his original composite battalion of Virginians), supported by four artillery.[83][84] The vanguard advanced along the Englishtown road towards Monmouth Court House until it reached the junction with the road north to Foreman's Mill at around 09:30. Lee went forward with Wayne to reconnoiter Monmouth Court House, where they discovered the British rearguard. Estimating the British strength at some 2,000 men, Lee decided on a plan to hook round to their rear. He left Wayne with orders to fix the rearguard in place and returned to the rest of the vanguard to lead it on a left flanking maneuver. Lee's confidence crept into reports back to Washington that implied "the certainty of success."[85]

After Lee departed, Butler's detachment exchanged fire with mounted troops screening the rearguard, prompting the British to begin withdrawing to the northeast, towards the main column. In the subsequent pursuit, Wayne repulsed a charge by British dragoons and launched a feint against the British infantry, prompting the rearguard to halt and form up on a hill at the junction of the Middletown and Shrewsbury roads.[86] Meanwhile, because Lee was leading the rest of the vanguard himself, he neglected to provide Scott and Maxwell with a detailed plan.[87] After a two-mile (three-kilometer) march, he emerged from some woods at around 10:30, in time to witness Wayne's troops in action to his left.[88]

When it became evident the British were present in considerably larger numbers than he had anticipated, Lee operated with Lafayette to secure what he considered to be a vulnerable right flank. On the left flank, the appearance of another British force 2,000–3,000 strong prompted Jackson to pull his regiment back from its isolated position on the banks of Spotswood North Brook.[89] In the vanguard center, Scott and Maxwell, who was to Scott's left, were not in communication with Lee and not privy to his plan. They felt increasingly isolated watching Lee push out the right flank, and with British troops marching towards Monmouth Court House to their south, they became apprehensive about being cut off. They agreed between themselves to adjust their positions; Scott fell back a short distance southwest across the Spotswood Middle Brook to a more defensible position while Maxwell pulled back with the intention of circling round and coming up on Scott's right flank.[90][91]

Lee was dumbfounded when the two staff officers he had sent with orders for Scott returned with the news that he was nowhere to be found and disconcerted by their reports of the British returning in force. When he observed part of Lafayette's force retreating after a failed attempt to silence some British artillery, it appeared to Lee that the right flank too was pulling back without orders. It had become clear that he was losing control of the vanguard, and with his immediate command now only 2,500 strong, he realized his plan to envelop the British rearguard was finished. His priority now was the safety of his command in the face of superior numbers.[92]

Counter-attack and retreat

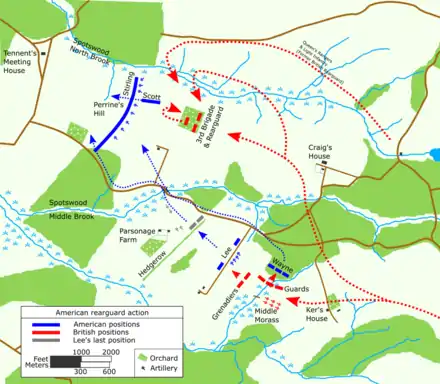

As soon as he received news that his rearguard was being probed, Clinton ordered Cornwallis to march the first division back towards Monmouth Court House. He believed Washington's main body was not close enough to come up in support and that the terrain would make it difficult for Lee to maneuver. He intended to do more than simply defend his baggage train; he thought the vanguard was vulnerable, and saw an opportunity to turn its right flank, just as Lee had feared, and destroy it.[93] After pausing at Monmouth Court House, Clinton began to push westwards. He formed his best troops into two columns, Guards on the right, Grenadiers on the left and the guns of the Royal Artillery between them, while a regiment of dragoons ranged about them. The infantry of the 3rd and 4th Brigades followed in line, while the 5th Brigade remained in reserve at Monmouth Court House. The Queen's Rangers and the infantry of the rearguard operated on the British right flank. To the rear, a brigade of Hessian grenadiers remained in a defensive line to which Clinton could fall back if things went badly.[94] In total, his force comprised some 10,000 troops.[95]

Lee ordered a general retreat to a line about one mile (two kilometers) to the west of Monmouth Court House that ran from Craig's House, north of Spotswood Middle Brook, to Ker's House, south of the brook. He had significant difficulties communicating with his subordinates and exhausted his aides attempting to do so. Although he arrived in the vicinity of Ker's house with a sizeable force by noon, he was unable to exercise command and control of it as a unified organization. As disorganized as the retreat was for Lee, at unit level it was generally conducted with a discipline that did credit to Steuben's training. The Americans suffered only some one dozen casualties as they fell back, an indication of how little major fighting there was; there were no organized volleys by infantry muskets, and only the artillery engaged in any significant action.[96] Lee believed he had conducted a model "retrograde manoeuver in the face and under fire of an enemy" and claimed his troops moved with "order and precision."[lower-alpha 11] He had remained calm during the retreat but began to unravel at Ker's house. When two of Washington's aides informed Lee that the main body was still some two miles (three kilometers) away and asked him what to report back, Lee replied "that he really did not know what to say."[98] Crucially, he failed to keep Washington informed of the retreat.[99]

Lee realized that a knoll in front of his lines would give the British, now deployed from column into line formation, command of the ground and render his position untenable. With no knowledge of the main body's whereabouts and believing he had little choice, Lee decided to fall back farther, across the Spotswood Middle Brook bridge. He believed he would be able to hold the British there from Perrine's Hill until the main body came up in support. With his aides out of action, Lee pressed whomever he could find into service as messengers to organize the withdrawal. It was during this period that he sent the army auditor, Major John Clark, to Washington with news of the retreat. But Washington was by now aware, having learned from Lee's troops who had already crossed the ravine.[100][101]

Washington's arrival

The main body had reached Englishtown at 10:00, and by noon it was still some four miles (six kilometers) from Monmouth Court House. Without any recent news from Lee, Washington had no reason to be concerned. At Tennent's Meeting House, some two miles (three kilometers) east of Englishtown, he ordered Greene to take Brigadier General William Woodford's brigade of some 550 men and 4 artillery pieces south then east to cover the right flank. The rest of the main body continued east along the Englishtown–Monmouth Court House road. In the space of some ten minutes, Washington's confidence gave way to alarm as he encountered a straggler bearing the first news of Lee's retreat and then whole units in retreat. None of the officers Washington met could tell him where they were supposed to be going or what they were supposed to be doing. As the commander-in-chief rode on ahead, over the bridge and towards the front line, he saw the vanguard in full retreat but no sign of the British. At around 12:45, Washington found Lee marshalling the last of his command across the middle morass, marshy ground southeast of the bridge.[102]

Expecting praise for a retreat he believed had been generally conducted in good order, Lee was uncharacteristically lost for words when Washington asked without pleasantries, "I desire to know, sir, what is the reason – whence arises this disorder and confusion?"[103] When he regained his composure, Lee attempted to explain his actions. He blamed faulty intelligence and his officers, especially Scott, for pulling back without orders, leaving him no choice but to retreat in the face of a superior force, and reminded Washington that he had opposed the attack in the first place.[103][104] Washington was not convinced; "All this may be very true, sir," he replied, "but you ought not to have undertaken it unless you intended to go through with it."[103] Washington made it clear he was disappointed with Lee and rode off to organize the battle he felt his subordinate should have given. Lee followed at a distance, bewildered and believing he had been relieved of command.[105][lower-alpha 12]

With the main body still arriving and the British no more than one-half mile (one kilometer) away, Washington began to rally the vanguard to set up the very defenses Lee had been attempting to organize. The commander-in-chief directed Wayne to take three battalions and form a rearguard in the Point of Woods, south of the Spotswood Middle Brook, that could delay the British. He issued orders for the 2nd New Jersey Regiment and two smaller Pennsylvanian regiments to deploy on the slopes of Perrine's Hill, north of the brook overlooking the bridge; they would be the rallying point for the rest of the vanguard and the position on which the main body would form. Washington offered Lee a choice: remain and command the rearguard, or fall back to and organize the main body. Lee opted for the former and, as Washington departed to take care of the latter, promised he would "be the last one to leave the field."[107][110]

American rearguard action

Lee positioned himself with four guns supported by two infantry battalions on the crest of a hill to the right of Wayne. As the British advanced – Guards on the right, Grenadiers on the left – they passed the Point of Woods, oblivious to the Continentals concealed in them. Wayne's troops inflicted up to forty casualties. The Guards reacted as they were trained and with the support of the dragoons and some of the Grenadiers, crashed into the Americans at the charge. Within ten minutes, Wayne's three battalions were being chased back to the bridge. The rest of the Grenadiers, meanwhile, continued to advance on Lee's position, pushing the Continental artillery back to a hedgerow to which the two infantry battalions had already withdrawn. Another short, sharp fight ensued until Lee, seeing both flanks being turned, ordered his men to follow Wayne back across the bridge.[111][112]

As Lee and Wayne fought south of the Spotswood Middle Brook, Washington was deploying the main body on Perrine's Hill, northwest of the bridge across the brook. Stirling's wing had just taken up positions on the American left flank when its artillery started to engage troops of the British 3rd Brigade. Clinton had earlier ordered the brigade to move right, cross the brook and cut the vanguard's line of retreat at the bridge. After the infantry of the 42nd (Royal Highland) Regiment of Foot crossed the brook, they ran into three battalions of Scott's detachment retreating westwards. Under pressure from the Highlanders, the Continentals continued through an orchard to the safety of Stirling's line while Stirling's artillery forced the Highlanders back to the orchard. A second battalion of Highlanders and the 44th Regiment of Foot that had swung right and crossed the Spotswood North Brook were also persuaded by the artillery to retreat. Even farther to the right, an attempt to outflank Stirling's position by the Queen's Rangers and the light infantry of the rearguard lacked the strength to carry it through, and they too fell back to join the 3rd Brigade.[113]

At 13:30, Lee was one of the last American officers to withdraw across Spotswood Middle Brook. The rearguard action had lasted no more than thirty minutes, enough time for Washington to complete the deployment of the main body. When a battalion of Grenadiers led by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Monckton chased Lee's troops over the bridge, the British found themselves facing Wayne's detachment reforming some 350 yards (320 m) away. As the Grenadiers advanced to engage Wayne they came under heavy fire from Stirling's artillery, another 350 yards (320 m) behind Wayne. Monckton became the highest-ranking British casualty of the day, and in the face of an unexpectedly strong enemy, the Grenadiers retreated back across the bridge to the hedgerow from which they had expelled Lee earlier.[114]

Washington had acted decisively to form a strong defensive position anchored on the right above the bridge on the Englishtown road and extending in a gentle curve one-half mile (one kilometer) up the slope of Perrine's Hill. When Lee joined it, Washington sent him with two battalions of Maxwell's New Jersey Brigade, around half of Scott's detachment and some other units of the former vanguard to form a reserve at Englishtown. The rest of the vanguard, which included the other half of Scott's detachment and most of Wayne's, remained with Washington.[115][lower-alpha 13] The infantry battle gave way to a two-hour artillery duel across the 1,200 yards (1,097 m) of no-man's land on either side of the brook, in which both sides suffered more casualties due to heat exhaustion than they did from enemy cannon.[117]

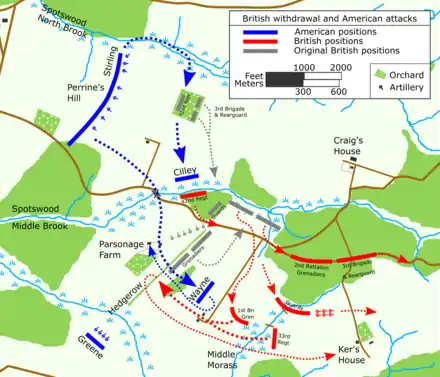

British withdrawal

Clinton had lost the initiative. He saw no prospect of success assaulting a strong enemy position in the brutal heat, and decided to break off the engagement.[119] His first task was to bring in his isolated right flank – the 3rd Brigade, Rangers and light infantry still sheltering in the orchard north of Spotswood Middle Brook. While the Highlanders of the 42nd Regiment remained in place to cover the withdrawal, the remainder fell back across the brook to join the Grenadiers at the hedgerow. Around 15:45, while the withdrawal was in progress, Greene arrived with Woodford's brigade at Combs Hill overlooking the British left flank and opened fire with his artillery. Clinton was forced to withdraw his own artillery, bringing the cannonade with Washington's guns on Perrine's Hill to an end, and move the Grenadiers to sheltered ground at the north end of the hedgerow.[120]

At 16:30, Washington learned of 3rd Brigade's withdrawal and launched the first American offensive action in six hours. He ordered two battalions of picked men "to go and see what [you] could do with the enemy's right wing."[121] Only one battalion some 350 strong led by Colonel Joseph Cilley actually made it into action. Cilley made good use of cover along the Spotswood North Brook to close with and engage the 275–325 troops of the 42nd Regiment in the orchard. The Highlanders found themselves in a disadvantageous position and, with the rest of British right flank already departed, they had no reason to stay. They conducted a fighting retreat in good order with minimal casualties. To the British, the rebels were "unsuccessful in endeavouring to annoy." To the Americans, it was a significant psychological victory over one of the British Army's most feared regiments.[122]

As his right flank pulled back, Clinton issued orders for what he intended to be a phased general withdrawal back towards Monmouth Court House.[123] His subordinates misunderstood. Instead of waiting until the 3rd Brigade had rejoined before pulling back, all but the 1st Grenadier Battalion withdrew immediately, leaving it and the 3rd Brigade dangerously exposed. Washington was buoyed by what he saw of Cilley's attack, and although he lacked specific intelligence about what the British were doing, the fact that their artillery had gone quiet suggested they might be vulnerable. He ordered Wayne to conduct an opportunistic advance with a detachment of Pennsylvanians.[124]

Wayne's request for three brigades, some 1,300 men, was denied, and at 16:45 he crossed the bridge over Spotswood Middle Brook with just 400 troops of the Third Pennsylvania Brigade.[lower-alpha 14] The Pennsylvanians caught the 650–700 men of the lone Grenadier battalion in the process of withdrawing, giving the British scant time to form up and receive the attack. The Grenadiers were "losing men very fast", Clinton wrote later, before the 33rd Regiment of Foot arrived with 300–350 men to support them. The British pushed back, and the Pennsylvanian Brigade began to disintegrate as it retreated to Parsonage farm. The longest infantry battle of the day ended when the Continental artillery on Combs Hill stopped the British counter-attack in its tracks and forced the Grenadiers and infantry to withdraw.[126][lower-alpha 15]

Washington planned to resume the battle the next day, and at 18:00 he ordered four brigades he had previously sent back to the reserve at Englishtown to return. When they arrived, they took over Stirling's positions on Perrine's Hill, allowing Stirling to advance across the Spotswood Middle Brook and take up new positions near the hedgerow. An hour later, Washington ordered a reinforced brigade commanded by Brigadier General Enoch Poor to probe Clinton's right flank while Woodford's brigade was to drop down from Combs Hill and probe Clinton's left flank. Their cautious advance was halted by sunset before making contact with the British, and the two armies settled down for the night within one mile (two kilometers) of each other, the closest British troops at Ker's House.[131]

While the battle was raging, Knyphausen had led the baggage train to safety. His second division endured only light harassment from militia along the way, and eventually set up camp some three miles (five kilometers) from Middletown. With the baggage train secure, Clinton had no intention of resuming the battle. At 23:00, he began withdrawing his troops. The first division slipped away unnoticed by Washington's forward troops and, after an overnight march, linked back up with Knyphausen's second division between 08:00 and 09:00 the next morning.[132]

Aftermath

_cropped.jpg.webp)

On June 29, Washington withdrew his army to Englishtown, where they rested the next day. The British were in a strong position near Middletown, and their route to Sandy Hook was secure. They completed the march largely untroubled by a militia that considered the threat to have passed and had melted away to tend to crops. The last British troops embarked on naval transports on July 6, and the Royal Navy carried Clinton's army to New York. The timing was fortuitous for the British; on July 11, a superior French fleet commanded by Vice Admiral Charles Henri Hector d'Estaing anchored off Sandy Hook.[133]

The battle was tactically inconclusive and strategically irrelevant; neither side dealt a heavy blow to the other, and the Continental Army remained in the field while the British Army redeployed to New York, just as both would have if the battle had never been fought.[134][lower-alpha 16] Clinton reported 358 total casualties after the battle – 65 killed, 59 died of fatigue, 170 wounded and 64 missing. Washington counted some 250 British dead, a figure later revised to a little over 300. Using a typical 18th-century wounded-to-killed ratio of no more than four to one and assuming no more than 160 British dead caused by enemy fire, Lender and Stone calculate the number of wounded could have been up to 640. A Monmouth County Historical Association study estimates total British casualties at 1,134 – comprising 304 dead, 770 wounded and 60 prisoners. Washington reported his own casualties to be 370 – comprising 69 dead, 161 wounded and 140 missing. Using the same wounded-to-killed ratio and assuming a proportion of the missing were fatalities, Lender and Stone estimate Washington's casualties could have exceeded 500.[140][141]

Claims of victory

In his post-battle report to Lord George Germain, Secretary of State for the Colonies, Clinton claimed he had conducted a successful operation to redeploy his army in the face of a superior force. The counter-attack was, he reported, a diversion intended to protect the baggage train and was ended on his own terms, though in private correspondence he conceded that he had also hoped to inflict a decisive defeat on Washington.[142] Having marched his army through the heart of enemy territory without the loss of a single wagon, he congratulated his officers on the "long and difficult retreat in the face of a greatly superior army without being tarnished by the smallest affront." While some of his officers showed a grudging respect for the Continental Army, their doubts were rooted not in the battlefield but in the realisation that the entry of France into the conflict had swung the strategic balance against Great Britain.[143]

For Washington, the battle was fought at a time of serious misgivings about his effectiveness as commander-in-chief, and it was politically important for him to present it as a victory.[144] On July 1, in his first significant communication to Congress from the front since the disappointments of the previous year, he wrote a full report of the battle. The contents were measured but unambiguous in claiming a significant win, a rare occasion on which the British had left the battlefield and their wounded to the Americans. Congress received it enthusiastically and voted a formal thanks to Washington and the army to honor "the important victory of Monmouth over the British grand army."[145]

In their accounts of the battle, Washington's officers invariably wrote of a major victory, and some took the opportunity to finally put an end to criticism of Washington; Hamilton and Lieutenant Colonel John Laurens, another of Washington's aides, wrote to influential friends – in the case of Laurens, his father Henry, President of the Continental Congress – praising Washington's leadership. The American press portrayed the battle as a triumph with Washington at its center. Governor William Livingston of New Jersey, who never came any nearer to Monmouth Court House during the campaign than Trenton, almost twenty-five miles (forty kilometers) away, published an anonymous 'eyewitness' account in the New Jersey Gazette only days after the battle, in which he credited the victory to Washington. Articles were still being published in a similar vein in August.[146]

Congressional delegates who were not Washington partisans, such as Samuel Adams and James Lovell, were reluctant to credit Washington but obliged to recognize the importance of the battle and keep to themselves any questions they might have had about the British success in reaching New York. The Washington loyalist Elias Boudinot wrote that "none dare to acknowledge themselves his Enemies."[147] Washington's supporters were emboldened in defending his reputation; in July, Major General John Cadwalader challenged Conway, the officer at the center of what Washington had perceived to be a conspiracy to remove him as commander-in-chief, to a duel in Philadelphia in which Conway was wounded in the mouth. Thomas McKean, chief justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania, was perhaps the only congressional delegate to register his disapproval of the affair, but did not think it wise to bring Cadwalader up before the court to answer for it.[148][149] Faith in Washington had been restored, Congress became almost deferential to him, public criticism of him all but ceased and for the first time he was hailed as the Father of his Country. The epithet became commonplace by the end of the year, by which time the careers of most of his chief critics had been eclipsed or were in ruins.[150][151][152]

Lee's court martial

Even before the day was out, Lee was cast in the role of villain, and his vilification became an integral part of the narrative Washington's lieutenants constructed when they wrote in praise of their commander-in-chief.[153] Lee continued in his post as second-in-command immediately after the battle, and it is likely that the issue would have simply subsided if he had let it go. But on June 30, after protesting his innocence to all who would listen, Lee wrote an insolent letter to Washington in which he blamed "dirty earwigs" for turning Washington against him, claimed his decision to retreat had saved the day and pronounced Washington to be "guilty of an act of cruel injustice" towards him. Instead of the apology Lee was tactlessly seeking, Washington replied that the tone of Lee's letter was "highly improper" and that he would initiate an official inquiry into Lee's conduct. Lee's response demanding a court-martial was again insolent; Washington ordered his arrest and set about obliging him.[154][155][156]

The court convened on July 4, and three charges were laid before Lee: disobeying orders in not attacking on the morning of the battle, contrary to "repeated instructions"; conducting an "unnecessary, disorderly, and shameful retreat"; and disrespect towards the commander-in-chief. The trial concluded on August 12, but the accusations and counter-accusations continued until the verdict was confirmed by Congress on December 5.[157] Lee's defense was articulate but fatally flawed by his efforts to turn it into a personal contest between himself and Washington. He denigrated the commander-in-chief's role in the battle, calling Washington's official account "from beginning to end a most abominable damn'd lie", and disingenuously cast his own decision to retreat as a "masterful manoeuvre" designed to lure the British onto the main body.[158] Washington remained aloof from the controversy, but his allies portrayed Lee as a traitor who had allowed the British to escape and linked him to the previous winter's alleged conspiracy against Washington.[159]

Although the first two charges proved to be dubious,[lower-alpha 17] Lee was undeniably guilty of disrespect, and Washington was too powerful to cross.[162] As the historian John Shy noted, "Under the circumstances, an acquittal on the first two charges would have been a vote of no-confidence in Washington."[163] Lee was found guilty on all three counts, though the court deleted "shameful" from the second and noted the retreat was "disorderly" only "in some few instances." Lee was suspended from the army for a year, a sentence so lenient that some interpreted it as a vindication of all but the charge of disrespect.[164] Lee's fall from grace removed Washington's last significant critic from the army and the last realistic alternative to Washington as commander-in-chief, and silenced the last voice to speak in favor of a militia army. Washington's position as the "indispensable man" was now unassailable.[165][lower-alpha 18]

Assessing the Continental Army

Joseph Bilby and Katherine Jenkins consider the battle to have marked the "coming of age" of a Continental Army that had previously achieved success only in small actions at Trenton and Princeton.[172] Their view is reflected by Joseph Ellis, who writes of Washington's belief that "the Continental Army was now a match for British professionals and could hold its own in a conventional, open-field engagement."[173] Mark Lender and Garry Stone point out that while the Continental Army was unquestionably improved under Steuben's tutelage, the battle did not test its ability to meet a professional European army in European-style warfare in which brigades and divisions maneuvered against each other. The only army to mount any major offensive operation on the day was British; the Continental Army fought a largely defensive battle from cover, and a significant portion of it remained out of the fray on Perrine's Hill. The few American attacks, such as Cilley's, were small-unit actions.[174]

Steuben's influence was apparent in the way the rank and file conducted themselves. Half of the troops who marched onto the battlefield at Monmouth in June were new to the army, having been recruited only since January. The significant majority of Lee's vanguard comprised ad hoc battalions filled with men picked from numerous regiments. Without any inherent unit cohesion, their effectiveness depended on officers and men who had never before served together using and following the drills they had been taught. That they did so competently was demonstrated throughout the battle, in the advance to contact, Wayne's repulse of the dragoons, the orderly retreat in the face of a strong counter-attack and Cilley's attack on the Highlanders. The army was well served too by the artillery, which earned high praise from Washington.[175] The professional conduct of the American troops gained widespread recognition even among the British; Clinton's secretary wrote, "the Rebels stood much better than ever they did", and Brigadier General Sir William Erskine, who as commander of the light infantry had traded blows with the Continentals, characterized the battle as a "handsome flogging" for the British, adding, "We had not receiv'd such an one in America."[176]

Legacy

In keeping with a battle that was more politically than militarily significant, the first reenactment in 1828 was staged to support the presidential candidacy of Andrew Jackson. In another attempt to reenact the battle in 1854, the weather added an authentic touch to the proceedings and the reenactment was called off due to the excessive heat. As the battle receded into history so too did its brutality, to be replaced by a sanitized romanticism. The public memory of the fighting was populated with dramatic images of heroism and glory, as epitomized by Emanuel Leutze's Washington Rallying the Troops at Monmouth.

The transformation was aided by the inventiveness of 19th-century historians, none more creative than Washington's step-grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, whose account of the battle was as artistic as Leutze's painting. Custis was inevitably derogatory towards Lee, and Lee's calumny achieved an orthodoxy in such works as Washington Irving's Life of George Washington (1855–1859) and George Bancroft's History of the United States of America, from the Discovery of the American Continent (1854–1878). The role Lee had unsuccessfully advanced for the militia in the revolution was finally established in the poetic 19th-century popular narrative, in which the Continental Army was excised from the battle and replaced with patriotic citizen-soldiers.[177]

The battlefield remained largely undisturbed until 1853, when the Freehold and Jamesburg Agricultural Railroad opened a line that cut through the Point of Woods, across the Spotswood Middle Brook and through the Perrine estate. The area became popular with tourists, and the Parsonage, the site of Wayne's desperate battle with the Grenadiers and the 33rd Regiment, was a favorite attraction until it was demolished in 1860.[178] During the 19th century, forests were cleared and marshes drained, and by the early 20th century traditional agriculture had been replaced by orchards and truck farms.[179] In 1884, the Monmouth Battle Monument was dedicated outside the modern-day county courthouse in Freehold, near where Wayne's troops first brushed with the British rearguard.[180] In the mid 20th century, two battlefield farms were sold to builders, but before the land could be developed, lobbying by state officials, Monmouth County citizens, the Monmouth County Historical Association and the Monmouth County Chapter of the Sons of the American Revolution succeeded in initiating a program of preservation. In 1963, the first tract of battlefield land came under state ownership with the purchase of a 200-acre farm. The Monmouth Battlefield State Park was dedicated on the bicentennial of the battle in 1978 and a new visitor center was opened in 2013. By 2015, the park encompassed over 1,800 acres, incorporating most of the land on which the afternoon battle was fought. The state park helped restore a more realistic interpretation of the history of the battle to the public memory, and the Continental Army takes its rightful place in the annual reenactments staged every June.[179][181][182]

Legend of Molly Pitcher

Five days after the battle, a surgeon treating the wounded reported a patient's story of a woman who had taken her husband's place working a gun after he was incapacitated. Two accounts attributed to veterans of the battle that surfaced decades later also speak of the actions of a woman during the battle; in one she supplied ammunition to the guns, in the other she brought water to the crews. The story gained prominence during the 19th century and became embellished as the legend of Molly Pitcher. The woman behind Molly Pitcher is most often identified as Mary Ludwig Hays, whose husband William served with the Pennsylvania State Artillery, but it is likely that the legend is an amalgam of more than one woman seen on the battlefield that day; it was not unusual for camp followers to assist in 18th-century battles, though more plausibly in carrying ammunition and water than crewing the guns. Late 20th-century research identified a site near Stirling's artillery line as the location of a well from which the legendary Molly drew water, and a historic marker was placed there in 1992.[183][184]

See also

- List of American Revolutionary War battles

- American Revolutionary War § British northern strategy fails. Places 'Battle of Monmouth' in overall sequence and strategic context.

- New Jersey in the American Revolution

Footnotes

- The British force numbered around 17,660 combatants in total, though only some 10,000 belonged to the first division that was involved in the battle. A request for the second division to send a brigade and a regiment of dragoons once battle had been joined was never acted upon.[1]

- Despite Washington's fears, his detractors were never part of an organized conspiracy to oust him, and those in Congress who favored his removal as commander-in-chief were in the minority. Most delegates recognized that the Continental Army needed stability more than it needed a new leader.[11]

- Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand had turned up as a volunteer at Valley Forge claiming the title of Baron von Steuben, an intimacy with the Prussian king Frederick the Great and the rank of general in the Prussian Army, none of which was true. He was appointed Inspector General of the Army in May 1778. His work was recognized as one of the most important contributions to the eventual American victory in the last official letter Washington wrote as commander-in-chief in 1783.[24]

- It was Washington's habit to pull the best troops out of their regiments and form them into elite, ad hoc light infantry battalions of picked men.[55]

- According to Lender & Stone, the exact timing of Washington's offer to Lee to take command of the vanguard is not clear and may have come after the decision to send the additional troops under Wayne.[59] The historian John E. Ferling states it came before the decision.[60]

- As an indication of Lafayette's tenuous control over his command, Scott did not receive the orders to move to Englishtown. He continued on the assumption that the morning attack on Clinton was to proceed, and got to within a mile of what would have been a disastrous confrontation with the British before he finally learned that he was to withdraw.[63]

- The two brigades Lee took with him to Englishtown were severely under strength and together numbered only some 650 men.[65]

- Sources disagree on the exact size of Lee's vanguard. Lee himself stated he had 4,100 men under his command, while Wayne estimated 5,000.[66] The Washington biographer Ron Chernow quotes primary sources that put it at 5,000 or 6,000 troops, while Ferling gives a figure of 5,340.[67][60]

- In a letter written by Lee's aide dated June 28 and timed at 01:00, Morgan was ordered to coordinate with the vanguard "tomorrow morning", which Morgan interpreted to mean June 29. It was the first in a series of miscommunications that kept him out of the battle on June 28.[70]

- The Ranger detachment was operating well forward of the regiment's assigned position, having been ordered to chase down and capture a small party of rebels believed to have included Lafayette that had been spotted on a hill overlooking Monmouth Court House. It was in fact not Lafayette but Steuben, who, apparently oblivious to commotion he had caused, escaped with all but his hat, which ended up as a souvenir for the British.[80]

- There were some reports of disorder and poor discipline among the retreating troops, but at no stage was there any panic, and no unit broke. The artillery units were credited with exemplary spirit, and they in turn credited the infantry for protecting them at every stage.[97]

- According to Lender & Stone, the encounter between Washington and Lee "became part of the folklore of the Revolution, with various witnesses (or would-be witnesses) taking increasing dramatic license with their stories over the years."[106] Ferling writes of eyewitness testimony in which a furious Washington, swearing "till the leaves shook on the trees" according to Scott, called Lee a "damned poltroon" and relieved him of command.[107] Chernow reports the same quote from Scott, quotes Lafayette to assert that a "terribly excited" Washington swore and writes that Washington "banished [Lee] to the rear."[104] Bilby & Jenkins attribute the poltroon quote to Lafayette, then write that neither Scott nor Lafayette were present.[108] Lender & Stone are also skeptical, and assert that such stories are apocryphal nonsense which first appeared almost a half century or more after the event, that Scott was too far away to have heard what was said, and that Lee himself never accused Washington of profanity. According to Lender & Stone, "careful scholarship has conclusively demonstrated that Washington was angry but not profane at Monmouth, and he never ordered Lee off the field."[109]

- Shortly after Lee reached Englishtown, four brigades totaling some 2,200 fresh troops arrived, sent back by Washington from the main body, bringing the reserve's strength to over 3,000 men. Another arrival was Steuben, sent back by Washington to relieve Lee.[116]

- Wayne never forgave Major General Arthur St. Clair, serving as an aide to Washington, for allowing only one brigade. Lender & Stone argue that St. Clair was acting on the authority of Washington, and that the modest size of the force is indicative of Washington's desire to avoid risking a substantial part of his army in a major action.[125]

- According to Edward G. Lengel, Lieutenant Colonel Aaron Burr led the Pennsylvanian Brigade attack, not Wayne.[127] Lengel also writes that around the same time, a column of Guards and Grenadiers led by Cornwallis made an unsuccessful attack on Greene's position at Combs Hill, a claim also made in William Stryker's account of the battle, but Lender and Stone assert that such an attack was never ordered.[128][129][130]

- Bilby and Jenkins write that the two armies "fought to a standstill" at Monmouth and characterize a British defeat in terms of the wider strategic situation.[135] Willard Sterne Randall considers the fact that the British left the battlefield to Washington to be "technically the sign of a victory".[136] Chernow bases his conclusion that the battle ended in "something close to a draw" on conservative estimates of casualties.[137] David G. Martin writes that despite retaining the battlefield and suffering fewer casualties, Washington had failed to land a heavy blow on the British and that, from the British viewpoint, Clinton had conducted a successful rearguard action and protected his baggage train. Martin concludes that "the battle is perhaps best called a draw."[138] Lengel makes the same points in coming to the same conclusion.[139]

- According to the court-martial transcript, Lee's actions had saved a significant portion of the army.[154] Both Scott and Wayne testified that although they understood Washington wanted Lee to attack, at no stage did he explicitly give Lee an order to do so.[160] Hamilton testified that as he understood it, Washington's instructions allowed Lee the discretion to act as circumstances dictated.[73] Lender and Stone identify two separate orders Washington issued to Lee on the morning of June 28 in which the commander-in-chief made clear his expectation that Lee should attack unless "some very powerful circumstance" dictate otherwise and that Lee should "proceed with caution and take care the Enemy don't draw him into a scrape."[161]

- Lee continued to argue his case and rage against Washington to anyone who would listen, prompting both John Laurens and Steuben to challenge him to a duel. Only the duel with Laurens actually transpired, during which Lee was wounded. In 1780, he sent such an obnoxious letter to Congress that it terminated his service with the army. He died in 1782.[166][167][168] Lee's place in history was further tarnished in the 1850s when George H. Moore, the librarian at the New-York Historical Society, discovered a manuscript dated March 29, 1777, written by Lee while he was the guest of the British as a prisoner of war. It was addressed to the "Royal Commissioners", i.e. Lord Richard Howe and Richard's brother, Sir William Howe, respectively the British naval and army commanders in North America at the time, and detailed a plan by which the British might defeat the rebellion. Moore's discovery, presented in a paper titled The Treason of Charles Lee in 1858, influenced perceptions of Lee for decades. Although most modern scholars reject the idea that Lee was guilty of treason, it is given credence in some accounts, examples being Randall's account of the battle in George Washington: A Life, published in 1997, and Dominick Mazzagetti's Charles Lee: Self Before Country, published in 2013.[169][170][171]

References

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 172, 265, 276–277

- Ferling 2009 pp. 130–135, 140

- Martin 1993 p. 12

- Ferling 2009 pp. 147–148, 151–152

- Ellis 2004 p. 109

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 24

- Ferling 2009 pp. 126–128, 137

- Ferling 2009 pp. 141, 148

- Ferling 2009 p. 139

- Ferling 2009 pp. 152–153

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 41–43

- Ferling 2009 pp. 157–165

- Ferling 2009 p. 171

- Ferling 2009 pp. 161–164

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 42

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 7, 12, 14

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 12–15

- Chernow 2010 p. 442

- Ferling 2009 p. 175

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 28

- Ferling 2009 p. 118

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 60–64, 66

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 65–66, 68

- Ellis 2004 pp. 116–117

- Ferling 2009 pp. 84, 105, 175

- Chernow 2010 p. 443

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 110, 112, 117

- Ferling 2009 pp. 178–179

- Chernow 2010 p. 444

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 114–120

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 105, 118

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 76–82

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 85–86, 88–90

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 92–94

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 91

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 97–98, 123–124, 126–127

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 141–143

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 122

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 127, 131–132

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 127–141

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 121

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 140

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 150–154

- Martin 1993 p. 204

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 156–158

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 pp. 47–48

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. xviii, 212

- Adelberg 2010 pp. 32–33

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 211, 213

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 201, 214–216

- Ferling 2009 pp. 175–176

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 99–104, 173

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 161–167

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 172

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 pp. 26, 128

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 172–174

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 175–177

- Ferling 2009 pp. 176–177

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 178

- Ferling 2009 p. 177

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 177–180

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 181–182

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 182

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 186–189

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 189

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 187

- Chernow 2010 p. 446

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 188, 190, 234

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 168, 185, 234

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 194, 234–236

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 234

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 191–193

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 194

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 198

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 236–237

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 238–240

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 249, 468

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 190

- Lander & Stone 2016 pp. 240–248

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 241–245, 248

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 250–253

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 pp. 188–189

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 pp. 186, 195

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 253

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 253–255, 261

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 255, 256, 258–260

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 256

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 261–263

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 262–264

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp.265–266

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 199

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 266–269

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 264–265, 273

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 273–274, 275

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 265

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 268–272

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 269, 271–272

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 270–271

- Ferling 2009 p. 178

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 278–281, 284

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 203

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 281–286

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 289

- Chernow 2010 p. 448

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 289–290

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 290

- Ferling 2009 p. 179

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 205

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 290–291

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 291–295

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 298–310

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 pp. 208–209

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 274–276, 318

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 310–314

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 296–297, 315–316

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 316–317, 348

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 318, 320, 322–324

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 344–347

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 315, 331–332

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 333–335

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 336–337

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 335–340

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 340

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 340–341

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 341–342

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 341–347

- Lengel 2005 p. 303

- Lengel 2005 pp. 303–304

- Stryker 1927 pp. 211–213, cited in Lender & Stone 2016 p. 531

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 531

- Lander & Stone 2016 pp. 347–349

- Lander & Stone 2016 pp. 349–352

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 354–355, 372–373, 378–379

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. xiii, 382

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 pp. 233–234

- Randall 1997 p. 359

- Chernow 2010 p. 451

- Martin 1993 pp. 233–234

- Lengel 2005 pp. 304–305

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 366–369

- Martin 1993 pp. 232–233

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 p. 232

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. xii, 375–378

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. xiii–xiv, 382–383

- Lander & Stone 2016 pp. 349, 353, 383–384

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 309, 384–389

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 386

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 387–388

- Chernow 2010 p. 423

- Lander & Stone 2016 p. 390

- Ferling 2009 pp. 173, 182

- Longmore 1988 p. 208

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 391–392

- Ferling 2009 p. 180

- Chernow 2010 p. 452

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 392–393

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 395–396, 400

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 396, 397, 399

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 397–399

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 191–192

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 195–196

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 396

- Shy 1973, cited in Lender & Stone 2016, p. 396

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 396–397

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 403

- Ferling 2009 pp. 180–181

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 400–401

- Chernow 2010 p. 455

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 111–112

- Randall 1997 p. 358

- Mazzagetti 2013 p. xi

- Bilby & Jenkins 2010 pp. 233, 237

- Ellis 2004 p. 120

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 405–406

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 407–408

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 375, 405

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 429–436

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 432–433

- "Monmouth Battlefield Brochure and Map" (PDF). New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Lender & Stone 2016 p. 437

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 438–439

- "Monmouth Battlefield State Park". New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. Retrieved April 14, 2019.

- Lender & Stone 2016 pp. 326–330

- Martin 1993 pp. 228–229

Bibliography

- Adelberg, Michael S. (2010). The American Revolution in Monmouth County: The Theatre of Spoil and Destruction. Charleston, South Carolina: The History Press. ISBN 978-1-61423-263-6.

- Bilby, Joseph G. & Jenkins, Katherine Bilby (2010). Monmouth Court House: The Battle That Made the American Army. Yardley, Pennsylvania: Westholme Publishing. ISBN 978-1-59416-108-7.

- Chernow, Ron (2010). Washington, A Life (E-Book). London, United Kingdom: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-141-96610-6.

- Ellis, Joseph (2004). His Excellency: George Washington. New York, New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-1-4000-4031-5.

- Ferling, John E. (2009). The Ascent of George Washington: The Hidden Political Genius of an American Icon. New York, New York: Bloomsbury Press. ISBN 978-1-59691-465-0.

- Lender, Mark Edward & Stone, Garry Wheeler (2016). Fatal Sunday: George Washington, the Monmouth Campaign, and the Politics of Battle. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-5335-3.

- Lengel, Edward G. (2005). General George Washington: A Military Life. New York, New York: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4000-6081-8.

- Longmore, Paul K. (1988). The Invention of George Washington. Berkeley, California: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-06272-6.

- Martin, David G. (1993). The Philadelphia Campaign: June 1777–July 1778. Conshohocken, Pennsylvania: Combined Books. ISBN 978-0-938289-19-7.