Battle of Trenton

The Battle of Trenton was a small but pivotal American Revolutionary War battle that took place on the morning of December 26, 1776, in Trenton, New Jersey. After General George Washington's crossing of the Delaware River north of Trenton the previous night, Washington led the main body of the Continental Army against Hessian auxiliaries garrisoned at Trenton. After a brief battle, almost two-thirds of the Hessian force was captured, with negligible losses to the Americans. The battle significantly boosted the Continental Army's waning morale, and inspired re-enlistments.

| Battle of Trenton | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the American Revolutionary War | |||||||

Battle of Trenton, H. Charles McBarron Jr. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,400[2] | 1,500[3] | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

2 dead from exposure 5 wounded[4] |

22 killed 83 wounded 800–900 captured[5] | ||||||

The Continental Army had previously suffered several defeats in New York and had been forced to retreat through New Jersey to Pennsylvania. Morale in the army was low; to end the year on a positive note, George Washington—Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army—devised a plan to cross the Delaware River on the night of December 25–26 and surround the Hessians' garrison.

Because the river was icy and the weather severe, the crossing proved dangerous. Two detachments were unable to cross the river, leaving Washington with only 2,400 men under his command in the assault, 3,000 fewer than planned. The army marched 9 miles (14.5 km) south to Trenton. The Hessians had lowered their guard, thinking they were safe from the Americans' army, and had no long-distance outposts or patrols. Washington's forces caught them off guard, and after a short but fierce resistance, most of the Hessians surrendered and were captured, with just over a third escaping across Assunpink Creek.

Despite the battle's small numbers, the victory inspired patriots and sympathizers of the newly formed United States. With the success of the ongoing revolution in doubt a week earlier, the army had seemed on the verge of collapse. The dramatic victory inspired soldiers to serve longer and attracted new recruits to the ranks.

Background

In early December 1776, American morale was very low.[6] The Americans had been ousted from New York by the British and their Hessian auxiliaries, and the Continental Army was forced to retreat across New Jersey. Ninety percent of the Continental Army soldiers who had served at Long Island were gone.[7] Men had deserted, feeling that the cause for independence was lost. Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, expressed some doubts, writing to his cousin in Virginia, "I think the game is pretty near up."[8]

At the time a small town in New Jersey, Trenton was occupied by four regiments of Hessian soldiers (numbering about 1,400 men) commanded by Colonel Johann Rall. Washington's force comprised 2,400 men, with infantry divisions commanded by Major Generals Nathanael Greene and John Sullivan, and artillery under the direction of Brigadier General Henry Knox.[9]

Prelude

Intelligence

George Washington had stationed a spy named John Honeyman, posing as a Tory, in Trenton. Honeyman had served with Major General James Wolfe in Quebec at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham on September 13, 1759, and had no trouble establishing his credentials as a Tory. Honeyman was a butcher and bartender, who traded with the British and Hessians. This enabled him to gather intelligence and to convince the Hessians that the Continental Army was in such a low state of morale that they would not attack Trenton. Shortly before Christmas, he arranged to be captured by the Continental Army, who had orders to bring him to Washington unharmed. After being questioned by Washington, he was imprisoned in a hut to be tried as a Tory in the morning, but a small fire broke out nearby, enabling him to "escape".[10]

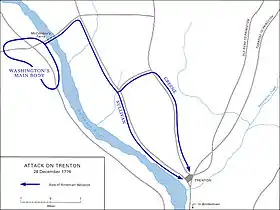

U.S. plan

The U.S. plan relied on launching coordinated attacks from three directions. General John Cadwalader would launch a diversionary attack against the British garrison at Bordentown, New Jersey, to block off reinforcements from the south. General James Ewing would take 700 militia across the river at Trenton Ferry, seize the bridge over the Assunpink Creek and prevent enemy troops from escaping. The main assault force of 2,400 men would cross the river 9 mi (14 km) north of Trenton and split into two groups, one under Greene and one under Sullivan, to launch a pre-dawn attack.[11] Sullivan would attack the town from the south, and Greene from the north.[7] Depending on the success of the operation, the Americans would possibly follow up with separate attacks on Princeton and New Brunswick.[6]

During the week before the battle, U.S. advance parties began to ambush enemy cavalry patrols, capturing dispatch riders and attacking Hessian pickets. The Hessian commander, to emphasize the danger to his men, sent 100 infantry and an artillery detachment to deliver a letter to the British commander at Princeton.[6] Washington ordered Ewing and his Pennsylvania militia to try to gain information on Hessian movements and technology.[12] Ewing instead made three successful raids across the river. On December 17 and 18, 1776, they attacked an outpost of jägers and on the 21st, they set fire to several houses.[12] Washington put constant watches on all possible crossings near the Continental Army encampment on the Delaware, as he believed William Howe would launch an attack from the north on Philadelphia if the river froze over.[13]

On December 20, 1776, some 2,000 troops led by General Sullivan arrived in Washington's camp.[14] They had been under the command of Charles Lee and had been moving slowly through northern New Jersey when Lee was captured. That same day, an additional 800 troops arrived from Fort Ticonderoga under the command of Horatio Gates.[14]

Hessian moves

On December 14, 1776, the Hessians arrived in Trenton to establish their winter quarters.[15] At the time, Trenton was a small town with about 100 houses and two main streets, King (now Warren) Street and Queen (now Broad) Street.[16] Carl von Donop, Rall's superior, had marched south to Mount Holly on December 22 to deal with the resistance in New Jersey, and had clashed with some New Jersey militia there on December 23.[17]

Donop, who despised Rall, was reluctant to give command of Trenton to him.[18] Rall was known to be loud and unacquainted with the English language,[18] but he was also a 36-year soldier with a great deal of battle experience. His request for reinforcements had been turned down by British commander General James Grant, who disdained the American rebels and thought them poor soldiers. Despite Rall's experience, the Hessians at Trenton did not admire their commander.[19]

Trenton lacked city walls or fortifications, which was typical of U.S. settlements.[20] Some Hessian officers advised Rall to fortify the town, and two of his engineers advised that a redoubt be constructed at the upper end of town and fortifications be built along the river.[20] The engineers went so far as to draw up plans, but Rall disagreed with them.[20] When Rall was again urged to fortify the town, he replied, "Let them come ... We will go at them with the bayonet."[20]

As Christmas approached, Loyalists came to Trenton to report the Americans were planning action.[8] U.S. deserters told the Hessians that rations were being prepared for an advance across the river. Rall publicly dismissed such talk as nonsense, but privately in letters to his superiors, he said he was worried about an imminent attack.[8] He wrote to Donop that he was "liable to be attacked at any moment". Rall said that Trenton was "indefensible" and asked that British troops establish a garrison in Maidenhead (now Lawrenceville). Close to Trenton, this would help defend the roads from Americans. His request was denied.[21] As the Americans disrupted Hessian supply lines, the officers started to share Rall's fears. One wrote, "We have not slept one night in peace since we came to this place."[22] On December 22, 1776, a spy reported to Grant that Washington had called a council of war; Grant told Rall to "be on your guard".[23]

The main Hessian force of 1,500 men was divided into three regiments: Knyphausen, Lossberg and Rall. That night, they did not send out any patrols because of the severe weather.[24]

Crossing and march

Before Washington and his troops left, Benjamin Rush came to cheer up the general. While he was there, he saw a note Washington had written, saying, "Victory or Death".[22] Those words would be the password for the surprise attack.[25] Each soldier carried 60 rounds of ammunition, and three days of rations.[26] When the army arrived at the shores of the Delaware, they were already behind schedule, and clouds began to form above them.[27] It began to rain. As the air's temperature dropped, the rain changed to sleet, and then to snow.[27] The Americans began to cross the river, with John Glover in command. The men went across in Durham boats, while the horses and artillery went across on large ferries.[28] The 14th Continental Regiment of Glover manned the boats. During the crossing, several men fell overboard, including Colonel John Haslet. Haslet was quickly pulled out of the water. No one died during the crossing, and all the artillery pieces made it over in good condition.[29]

Two small detachments of infantry of about 40 men each were ordered ahead of main columns.[30] They set roadblocks ahead of the main army and were to take prisoner whoever came into or left the town.[30] One of the groups was sent north of Trenton, and the other was sent to block River Road, which ran along the Delaware River to Trenton.[31]

The terrible weather conditions delayed the landings in New Jersey until 3:00 am; the plan was that they were supposed to be completed by 12:00 am. Washington realized it would be impossible to launch a pre-dawn attack. Another setback occurred for the Americans, as generals Cadwalader and Ewing were unable to join the attack because of the weather conditions.[11]

At 4:00 am, the soldiers began to march towards Trenton.[32] Along the way, several civilians joined as volunteers and led as guides (such as John Mott) because of their knowledge of the terrain.[33] After marching 1.5 miles (2.4 km) through winding roads into the wind, they reached Bear Tavern, where they turned south onto Bear Tavern Road .[34] The ground was slippery, but it was level, making it easier for the horses and artillery. They began to make better time.[34] They soon reached Jacobs Creek, where, with difficulty, the Americans made it across.[35] The two groups stayed together until they reached Birmingham (now West Trenton), where they split apart, with Greene’s force heading east to approach Trenton by the Scotch and Pennington roads and Sullivan’s heading southwest to approach via River Road.[7] Soon after, they reached the house of Benjamin Moore, where the family offered food and drink to Washington.[36] At this point, the first signs of daylight began to appear.[36] Many of the troops did not have boots, so they were forced to wear rags around their feet. Some of the men's feet bled, turning the snow to a dark red. Two men died on the march.[37]

As they marched, Washington rode up and down the line, encouraging the men to continue.[28] General Sullivan sent a courier to tell Washington that the weather was wetting his men's gunpowder. Washington replied, "Tell General Sullivan to use the bayonet. I am resolved to take Trenton."[38]

About 2 miles (3 km) outside the town, the main columns reunited with the advance parties.[39] They were startled by the sudden appearance of 50 armed men, but they were American. Led by Adam Stephen, they had not known about the plan to attack Trenton and had attacked a Hessian outpost.[40] Washington feared the Hessians would have been put on guard, and shouted at Stephen, "You sir! You Sir, may have ruined all my plans by having them put on their guard."[40] Despite this, Washington ordered the advance continue to Trenton. In the event, Rall thought the first raid was the attack which Grant had warned him about, and that there would be no further action that day.[41]

Battle

U.S. attack

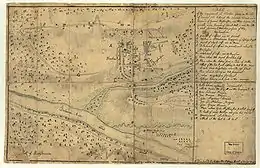

At 8 am, the outpost was set up by the Hessians at a cooper shop on Pennington Road about one mile northwest of Trenton. Washington led the assault, riding in front of his soldiers.[42] As the Hessian commander of the outpost, Lieutenant Andreas Wiederholdt, left the shop, an American fired at him but missed.[42] Wiederholdt immediately shouted, "Der Feind!" (The Enemy!) and other Hessians came out.[43] The Americans fired three volleys, and the Hessians returned one of their own.[42] Washington ordered Edward Hand's Pennsylvania Riflemen and a battalion of German-speaking infantry to block the road that led to Princeton. They attacked the Hessian outpost there.[43] Wiederholdt soon realized that this was more than a raiding party; seeing other Hessians retreating from the outpost, he led his men to do the same.[44] Both Hessian detachments made organized retreats, firing as they fell back.[43] On the high ground at the north end of Trenton, they were joined by a duty company from the Lossberg Regiment.[43] They engaged the Americans, retreating slowly, keeping up continuous fire and using houses for cover.[45] Once in Trenton, they gained covering fire from other Hessian guard companies on the outskirts of the town. Another guard company nearer to the Delaware River rushed east to their aid, leaving open the River Road into Trenton. Washington ordered the escape route to Princeton be cut off, sending infantry in battle formation to block it, while artillery formed at the head of King and Queen streets.[46]

Leading the southern U.S. column, General Sullivan entered Trenton by the abandoned River Road and blocked the only crossing over the Assunpink Creek to cut off the Hessian escape.[47] Sullivan briefly held up his advance to make sure Greene's division had time to drive the Hessians from their outposts in the north.[47] Soon after, they continued their advance, attacking the Hermitage, home of Philemon Dickinson, where 50 jägers under the command of Lieutenant von Grothausen were stationed.[47] Lieutenant von Grothausen brought 12 of his jägers into action against the advanced guard but had only advanced a few hundred yards when he saw a column of Americans advancing to the Hermitage.[47] Pulling back to the Hessian barracks, he was joined by the rest of the jägers. After the exchange of one volley, they turned and ran, some trying to swim across the creek, while others escaped over the bridge, which had not yet been cut off. The 20 British dragoons also fled.[47] As Greene and Sullivan's columns pushed into the town, Washington moved to high ground north of King and Queens streets to see the action and direct his troops.[48] By this time, U.S. artillery from the other side of the Delaware River had come into action, devastating the Hessian positions.[49]

With the sounding of the alarm, the three Hessian regiments began to prepare for battle.[50] The Rall regiment formed on lower King Street along with the Lossberg regiment, while the Knyphausen regiment formed at the lower end of Queen Street.[50] Lieutenant Piel, Rall's brigade adjutant, woke his commander, who found that the rebels had taken the "V" of the main streets of the town. This is where the engineers had recommended building a redoubt. Rall ordered his regiment to form up at the lower end of King Street, the Lossberg regiment to prepare for an advance up Queen Street, and the Knyphausen regiment to stand by as a reserve for Rall's advance up King Street.[47]

The U.S. cannon stationed at the head of the two main streets soon came into action. In reply, Rall directed his regiment, supported by a few companies of the Lossberg regiment, to clear the guns.[51] The Hessians formed ranks and began to advance up the street, but their formations were quickly broken by the U.S. guns and fire from Mercer's men who had taken houses on the left side of the street.[51] Breaking ranks, the Hessians fled. Rall ordered two three-pound cannon into action. After getting off six rounds each, within just a few minutes, half of the Hessians manning their guns were killed by the U.S. cannon.[51] After the men fled to cover behind houses and fences, their cannons were taken by the Americans.[52] Following capture of the cannon, men under the command of George Weedon advanced down King Street.[47]

On Queen Street, all Hessian attempts to advance up the street were repulsed by guns under the command of Thomas Forrest. After firing four rounds each, two more Hessian guns were silenced. One of Forrest's howitzers was put out of action with a broken axle.[47] The Knyphausen regiment became separated from the Lossberg and the Rall regiments. The Lossberg and the Rall regiments fell back to a field outside of town, taking heavy losses from grapeshot and musket fire. In the southern part of the town, Americans under command of Sullivan began to overwhelm the Hessians. John Stark led a bayonet charge at the Knyphausen regiment, whose resistance broke because their weapons would not fire. Sullivan led a column of men to block off escape of troops across the creek.[52]

Hessian resistance collapses

The Hessians in the field attempted to reorganize and make one last attempt to retake the town so they could make a breakout.[1] Rall decided to attack the U.S. flank on the heights north of the town.[53] Rall yelled "Forward! Advance! Advance!", and the Hessians began to move, with the brigade's band playing fifes, bugles and drums to help the Hessians' spirit.[53][54]

Washington, still on high ground, saw the Hessians approaching the U.S. flank. He moved his troops to assume battle formation against the enemy.[53] The two Hessian regiments began marching toward King Street but were caught in U.S. fire that came at them from three directions.[53] Some Americans had taken up defensive positions inside houses, reducing their exposure. Some civilians joined the fight against the Hessians.[55] Despite this, they continued to push, recapturing their cannon. At the head of King Street, Knox saw the Hessians had retaken the cannon and ordered his troops to take them. Six men ran and, after a brief struggle, seized the cannon, turning them on the Hessians.[56] With most of the Hessians unable to fire their guns, the attack stalled. The Hessians' formations broke, and they began to scatter.[55] Rall was mortally wounded.[57] Washington led his troops down from high ground while yelling, "March on, my brave fellows, after me!"[55] Most of the Hessians retreated into an orchard, with the Americans in close pursuit. Quickly surrounded,[58] the Hessians were offered terms of surrender, to which they agreed.

Although ordered to join Rall, the remains of the Knyphausen regiment mistakenly marched in the opposite direction.[58] They tried to escape across the bridge but found it had been taken. The Americans quickly swept in, defeating a Hessian attempt to break through their lines. Surrounded by Sullivan's men, the regiment surrendered, just minutes after the rest of the brigade.[59]

Casualties and capture

The Hessian forces lost 22 killed in action, including their commander Colonel Johann Rall, 83 wounded, and 896 captured–including the wounded.[60] The Americans suffered only two deaths during the march and five wounded from battle, including a near-fatal shoulder wound to future president James Monroe. Other losses incurred by the Patriots from exhaustion, exposure, and illness in the following days may have raised their losses above those of the Hessians.[61]

The captured Hessians were sent to Philadelphia and later Lancaster. In 1777 they were moved to Virginia.[62] Rall was mortally wounded and died later that night at his headquarters.[61] All four Hessian colonels in Trenton were killed in the battle. The Lossberg regiment was effectively removed from the British forces. Parts of the Knyphausen regiment escaped to the south, but Sullivan captured some 200 additional men, along with the regiment's cannon and supplies. They also captured approximately 1,000 arms and much-needed ammunition.[63] The Americans also captured their entire store of provisions—tons of flour, dried and salted meats, ale and other liquors, as well as shoes, boots, clothing and bedding—things that were as much needed by the ragtag Continental forces as weapons and horses.

Among those captured by the Patriots was Christian Strenge, later to become a schoolmaster and fraktur artist in Pennsylvania.[64]

Hessian drinking

An officer in Washington's staff wrote before the battle, "They make a great deal of Christmas in Germany, and no doubt the Hessians will drink a great deal of beer and have a dance to-night. They will be sleepy to-morrow morning."[65] Popular history commonly portrays the Hessians as drunk from Christmas celebrations. However, historian David Hackett Fischer quotes Patriot John Greenwood, who fought in the battle and supervised Hessians afterward, who wrote, "I am certain not a drop of liquor was drunk during the whole night, nor, as I could see, even a piece of bread eaten."[66] Military historian Edward G. Lengel wrote, "The Germans were dazed and tired but there is no truth to the legend claiming that they were helplessly drunk."[67]

Aftermath

After the Hessians' surrender, Washington is reported to have shaken the hand of a young officer and said, "This is a glorious day for our country."[68] On December 28, General Washington interviewed Lieutenant (later Colonel) Andreas Wiederhold, who detailed the failures of Rall's preparation.[69] Washington soon learned however that Cadwalader and Ewing had been unable to complete their crossing, leaving his worn-out army of 2,400 men isolated.[70] Without their 2,600 men, Washington realized he did not have the forces to attack Princeton and New Brunswick.[70]

By noon, Washington's force had moved across the Delaware back into Pennsylvania, taking their prisoners and captured supplies with them.[70] Washington would follow up his success a week later in the Battle of the Assunpink Creek and the Battle of Princeton solidifying Patriot gains.

Legacy

This small but decisive battle, as with the later Battle of Cowpens, had an effect disproportionate to its size. The Patriot victory gave the Continental Congress new confidence, as it proved colonial forces could defeat regulars. It also increased re-enlistments in the Continental Army forces. By defeating a European army, the colonials reduced the fear which the Hessians had caused earlier that year after the fighting in New York.[1] Howe was stunned that the Patriots so easily surprised and overwhelmed the Hessian garrison.[59] Colonial support for the rebellion was further buoyed significantly at this time by writings of Thomas Paine and additional successful actions by the New Jersey Militia.[71]

Two notable U.S. officers were wounded while leading the charge down King Street: William Washington, cousin of General Washington, and Lieutenant James Monroe, the future President of the United States. Monroe was carried from the field bleeding badly after he was struck in the left shoulder by a musket ball, which severed an artery. Doctor John Riker clamped the artery, preventing him from bleeding to death.[56]

The Trenton Battle Monument, erected at "Five Points" in Trenton, stands as a tribute to this U.S. victory.[72] The crossing of the Delaware River and battle are reenacted by local enthusiasts every year (unless the weather is too severe on the river).[73]

Eight current Army National Guard units (101st Eng Bn,[74] 103rd Eng Bn,[75] A/1-104th Cav,[76] 111th Inf,[77] 125th QM Co,[78] 175th Inf,[79] 181st Inf[80] and 198th Sig Bn[81]) and one currently-active Regular Army Artillery battalion (1–5th FA)[82] are derived from U.S. units that participated in the Battle of Trenton. There are thirty current units of the U.S. Army with colonial roots.

Painting

In 1851, German-American artist Emanuel Leutze painted the second of three painting depicting Washington crossing the Deleware. It is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and is "one of the most famous American paintings." At the time of its first exhibition it caused a sensation, in Europe and the United States. Leutze hoped it would stir revolutionary sentiments in Germany. After six months in Germany it was shipped to New York City where the New-York Mirror newspaper lauded it with the words, "the grandest, most majestic, and most effective painting ever exhibited in America."[83] The painting is the center-piece of the collections in the American Wing. It is still one of the most recognizable paintings at the Metropolitan. It is central to the canon of American historical art images, it monumental popularity undimmed in the years since it was first exhibited.[84]

See also

- American Revolutionary War §British New York counter-offensive. The 'Battle of Trenton' placed in overall sequence and strategic context.

- List of American Revolutionary War battles

- New Jersey in the American Revolution

- Battle of the Assunpink Creek – also known as the Second Battle of Trenton, fought one week later

- Battle of Princeton – fought the day after the Battle of the Assunpink Creek

- Battle of Yorktown

- Battles of Saratoga

- Battle of Bennington

Footnotes

- Wood p. 72

- Fischer p.391-393

- Fischer p.396

- Fischer p. 406

- Fischer p. 254—Casualty numbers vary slightly with the Hessian forces, usually between 21–23 killed, 80–95 wounded and 890–920 captured (including the wounded), but it is generally agreed that the casualties were in this area.

- Brooks p. 55

- Savas p. 84

- Ketchum p. 235

- Stanhope p. 129

- Van Dyke, John (1873), "An Unwritten Account of a Spy of Washington", Our Home

- Brooks p. 56

- Fischer p. 195

- Ketchum p. 242

- Savas p. 83

- Fischer p. 188

- Ketchum p. 233

- Rosenfeld p. 177

- Ketchum p. 229

- Lengel p. 183

- Fischer p. 189

- Fischer p. 197

- Ketchum p. 236

- Fischer p. 203

- Wood p. 65

- McCullough p. 273

- McCullough p. 274

- Fischer p. 212

- Ferling p. 176

- Fischer p. 219

- Fischer p. 221

- Fischer p. 222

- Fischer p. 223

- Fischer p. 225

- Fischer p. 226

- Fischer p. 227

- Fischer p. 228

- Scheer p. 215

- Kevin Wright. "The Crossing And Battle At Trenton – 1776". Bergen County Historical Society. Retrieved August 14, 2008.

- Fischer p.231

- Fischer p. 232

- McCullough p. 279

- Fischer p. 235

- Fischer p. 237

- Andreas Wiederholdt (edited by M.D. Learned and C. Grosse): Tagebuch des Capt. Wiederholdt Vom 7 Oktober bis 7 December 1780; The MacMillan Co, New York, ~1862; reprinted by the University of Michigan Library, 17 August 2015

- Ketchum p. 255

- Ketchum p. 256

- Wood p. 68

- McCullough p. 280

- Fischer p. 239

- Fischer p. 240

- Wood p. 70

- Wood p. 71

- Fischer p. 246

- Ketchum p. 262

- Fischer p. 249

- Fischer p. 247

- Fischer p. 248

- Fischer p. 251

- Wood p. 74

- Fischer p. 254

- Fischer p. 255

- Fischer p. 379

- Mitchell p. 43

- Brooklyn United. "Johann Christian Strenge – Self-Taught Genius". selftaughtgenius.org. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- Stryker p. 361

- Fischer p. 426

- Lengel p. 186

- Ferling p. 178

- Andreas Wiederholdt (edited by M.D. Learned and C. Grosse: Tagebuch des Capt. Widerholdt Vom 7 Oktober bis 7 December 1780; The MacMillan Co, New York, ~1862;reprinted by the University of Michigan Library, 17 August 2015

- Wood p. 75

- Fischer p. 143

- Burt p. 439

- "Cross With Us". Washington Crossing Historic Park.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 101st Engineer Battalion

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 103rd Engineer Battalion.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, Troop A/1st Squadron/104th Cavalry.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 111th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981. pp. 217–219.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 125th Quartermaster Company. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved February 29, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 175th Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1982, pp. 343–345.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 181st Infantry. Reproduced in Sawicki 1981, pp. 354–355.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 198th Signal Battalion.

- Department of the Army, Lineage and Honors, 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery.

- "10 Facts about Washington's Crossing of the Delaware River". George Washington's Mount Vernon.

- Barratt, Carrie; Mayer, Lance; Myers, Guy; Wilner, Eli; Smeaton, Suzanne (2012). Washington crossing the Delaware : restoring an American masterpiece. New York, N.Y.: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 3. ISBN 978-1-58839-439-2.

References

- Brooks, Victor (1999). How America Fought Its Wars. New York: De Capo Press. ISBN 1-58097-002-8.

- Burt, Daniel S. (2001). The Biography Book. New York: Oryx Press. ISBN 1-57356-256-4.

- Elson, William Henry (1908). History of the United States of America. Macmillan.

- Ferling, John (2007). Almost a Miracle. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-518121-0.

- Fischer, David Hackett (2006). Washington's Crossing. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517034-2.

- Ketchum, Richard (1999). The Winter Soldiers: The Battles for Trenton and Princeton (1st Owl books ed.). Holt Paperbacks. ISBN 0-8050-6098-7.

- Lengel, Edward (2005). General George Washington. New York: Random House Paperbacks. ISBN 0-8129-6950-2.

General George Washington Lengel.

- McCullough, David (2006). 1776. New York: Simon and Schuster Paperback. ISBN 0-7432-2672-0.

1776 David.

- Mitchell, Craig (2003). George Washington's New Jersey. Middle Atlantic Press. ISBN 0-9705804-1-X.

- Rosenfeld, Lucy (2007). George Washington's New Jersey. Rutgers. ISBN 978-0-8135-3969-0.

- Savas, Theodore (2006). Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution. Savas Beatie. ISBN 1-932714-12-X.

- Sawicki, James A. (1981). Infantry Regiments of the US Army. Dumfries, VA: Wyvern Publications. ISBN 978-0-9602404-3-2.

- Scheer, George (1987). Rebels and Redcoats. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80307-0.

- Stanhope, Phillip Henry (1854). History of England: From the Peace of Utrecht to the Peace of Versailles. GB, Murray.

- Wiederholdt, Andreas (2015) [1862]. M.D. Learned; C. Grosse (eds.). Tagebuch des Capt. Wiederholdt vom 7 Oktober bis 7 December 1780. The University of Michigan Library: The MacMillan Co, New York.

- Wood, W.J. Henry (2003). Battles of the Revolutionary War. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-81329-7.

- Tucker, Philip Thomas (2014), George Washington's Surprise Attack: A New Look at the Battle That Decided the Fate of America, Skyhorse Publishing (ISBN 978-1628736526)

Further reading

- Maloy, Mark. Victory or Death: The Battles of Trenton and Princeton, December 25, 1776 – January 3, 1777. Emerging Revolutionary War Series. El Dorado Hills, CA: Savas Beatie, 2018. ISBN 978-1-61121-381-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Trenton. |

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about Battles of Trenton and Princeton. |

- "The Two Battles of Trenton". The Trenton Historical Society.

- "The Winter Patriots: The Trenton-Princeton Campaign of 1776–1777". George Washington's Mount Vernon.