Oslo Airport, Gardermoen

Oslo Airport (Norwegian: Oslo lufthavn; IATA: OSL, ICAO: ENGM), alternatively spelt as Oslo Gardermoen Airport or simply Gardermoen Airport is the international airport serving Oslo, Norway, the capital and most populous city in the country. A hub for Norwegian Air Shuttle, Scandinavian Airlines, Widerøe and Wizz Air, it connects to 26 domestic and 158 international destinations.[3] Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, only 9 million passengers traveled through the airport in 2020.

Oslo Airport Oslo lufthavn | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||

| Operator | Avinor | ||||||||||||||

| Serves | Oslo, Eastern Norway | ||||||||||||||

| Location | Gardermoen, Ullensaker, Viken | ||||||||||||||

| Opened | 8 October 1998 | ||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 681 ft / 208 m | ||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 60°12′10″N 011°05′02″E | ||||||||||||||

| Website | www.avinor.no | ||||||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||||||

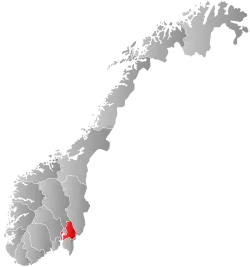

OSL Location in Akershus county Location of Akershus in Norway  | |||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2020) | |||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

The airport is located 19 nautical miles (35 km; 22 mi) northeast of Oslo, at Gardermoen in the municipality of Ullensaker, in Viken county.[4] It has two parallel roughly north–south runways measuring 3,600 metres (11,811 ft) and 2,950 metres (9,678 ft) and 71 aircraft stands, of which 50 have jet bridges. The airport is connected to the city center by the high-speed railway Gardermoen Line served by mainline trains and Flytoget. The percentage of passengers using public transport to get to and from the airport is one of the highest in the world at nearly 70%.[5] The ground facilities are owned by Oslo Lufthavn AS, a subsidiary of the state-owned Avinor. Also at the premises is Gardermoen Air Station, operated by the Royal Norwegian Air Force. An expansion with a new terminal building and a third pier opened in late April 2017.[6]

The airport location was first used by the Norwegian Army from 1940, with the first military airport facilities being built during the 1940s. The airport remained a secondary reserve and airport for chartered flights to Oslo Airport, Fornebu until 8 October 1998, when the latter was closed and an all-new Oslo Airport opened at Gardermoen, costing 11.4 billion Norwegian kroner (NOK).

Oslo is additionally served by the much smaller Sandefjord Airport, Torp in Sandefjord, which situated 119 km to the south of downtown Oslo and primarily used by leisure and low-cost carriers.

History

Military and secondary

The Norwegian army started using Gardermoen as a camp in 1740, although it was called Fredericksfeldt until 1788. It was first used by the cavalry, then by the dragoons and in 1789 by the riding marines. The base was also taken into use by the infantry from 1834 and by the artillery from 1860. Tents were solely used until 1860, when the first barracks and stalls were taken into use. Insulated buildings were built around 1900, allowing the camp to be used year-round. By 1925, the base had eleven camps and groups of buildings.[7] The first flight at Gardermoen happened in 1912, and Gardermoen became a station for military flights.[8]

During the occupation of Norway by Nazi Germany, the Luftwaffe took over Gardermoen, and built the first proper airport facilities with hangars and two crossing runways, both 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) long. After World War II, the airport was taken over by the Norwegian Air Force and made the main air station. Three fighter and one transport squadron were stationed at the Gardermoen.[7]

In 1946, Braathens SAFE established their technical base at the airport, but left two years later. Gardermoen also became the reserve airport for Oslo Airport, Fornebu, when the latter was closed due to fog. From 1946 to 1952, when a longer runway was built at Fornebu, all intercontinental traffic was moved to Gardermoen. Gardermoen grew up as a training field for the commercial airlines and as local airport for general aviation. Some commercial traffic returned again in 1960, when SAS received its first Sud Aviation Caravelle jet aircraft, that could not use the runway at Fornebu until it was extended again in 1962. SAS introduced a direct flight to New York in 1962, but it was quickly terminated.[9]

In 1972, capacity restraints forced the authorities to move all charter traffic from Fornebu to Gardermoen. However, SAS and Braathens SAFE were allowed to keep their charter services from Fornebu, so they would not have to operate from two bases.[10] A former hangar was converted to a terminal building and in 1974 passenger numbers were at 269,000 per year. In 1978, SAS started a weekly flight to New York. In 1983, further restrictions were enforced, and also SAS and Braathens SAFE had to move their charter operations to Gardermoen, increasing passenger numbers that year to 750,000. Several expansions of runway were made after the war, and by the 1985-extension the north-south runway was 3,050 metres (10,010 ft).[11]

Localization debate

The first airports to serve Oslo was Kjeller Airport that opened in 1912 and Gressholmen Airport that served seaplanes after its opening in 1926.[12] Norway's first airline, Det Norske Luftfartrederi, was founded in 1918 and the first scheduled fights were operated by Deutsche Luft Hansa to Germany with the opening of Gressholmen.[13] In 1939, a new combined sea and land airport opened at Fornebu.[14] It was gradually expanded, with a runway capable of jet aircraft opening in 1962 and a new terminal building in 1964. But due to its location on a peninsula about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi) from the city center and close to large residential areas, it would not be possible to expand the airport sufficiently to meet all foreseeable demand in the future.[15] Following the 1972 decision to move charter traffic to Gardermoen, politicians were forced to choose between a "divided solution" that planners stated would eventually force all international traffic to move to Gardermoen, or to build a new airport.[16]

Gardermoen had been proposed as a main airport for Oslo and Eastern Norway as early as 1946, both by the local newspaper Romerikes Blad and by Ludvig G. Braathen, who had just founded Braathens SAFE.[17] In 1970, a government report recommended that a new main airport be built at Hobøl, but stated that the time was still not right. The areas were therefore reserved.[18] During the 1970s, it became a political priority by the socialist and center parties to reduce state investments in Eastern Norway to stimulate growth in rural areas.[19] In 1983, parliament voted to keep the divided solution permanently, and expand Fornebu with a larger terminal.[20]

By 1985, traffic had increased so much that it became clear that by 1988 all international traffic would have to move to Gardermoen. The areas at Hobøl had been freed up, and a government report was launched recommending that a new airport be built at Gardermoen, although an airport at Hurum had also been surveyed. However, the report did not look into the need of the Air Force that was stationed at Gardermoen, and was therefore rejected by the parliament the following year. In 1988, a majority of the government chose Hurum as their preferred location, and Minister of Transport Kjell Borgen withdrew from his position. In 1989, new weather surveys from Hurum showed unfavorable conditions. There were large protests from meteorologists and pilots who stated that the surveys were manipulated. Two government committees were appointed, and both concluded that there were no irregularities in the surveys.[21]

Since Hurum could no longer be used, the government again recommended Gardermoen as the location. The Conservative Party instead wanted to build at Hobøl, but chose to support the Labour Party government's proposal to get a new airport as quickly as possible. Parliament passed legislation to build the new main airport at Gardermoen on 8 August 1992. At the same time, it was decided that a high-speed railway was to be built to Gardermoen, so the airport would have a 50% public transport market share.[22]

The choice of Gardermoen has spurred controversy, also after the matter was settled in parliament. In 1994, Engineer Jan Fredrik Wiborg, who claimed that falsified weather reports had been made, died after falling from a hotel window in Copenhagen. Circumstances about his death were never fully cleared up and documents about the weather case disappeared.[23][24] The Standing Committee on Scrutiny and Constitutional Affairs held a hearing about the planning process trying to identify any irregularities. An official report was released in 2001.[25][26]

Construction

To minimize the effect of using state grants to invest in Eastern Norway, parliament decided that the construction and operation of the airport was to be done by an independent limited company that would be wholly owned by the Civil Airport Administration (today Avinor). This model was chosen to avoid having to deal with public trade unions and to ensure that the construction was not subject to annual grants.[27] This company was founded in 1992 as Oslo Hovedflyplass AS, but changed its name in 1996 to Oslo Lufthavn. From 1 January 1997, it also took over the operation of Oslo Airport, Fornebu. The company was established with NOK 200 million in share capital. The remaining assets were NOK 2 billion from the sale of Fornebu and NOK 900 million in responsible debt. The remaining funding would come from debt from the state. Total investments for the airport, railways and roads were NOK 22 billion, of which Oslo Lufthavn would have a debt of NOK 11 billion after completion.[27]

At Gardermoen there was both an air station and about 270 house owners that had their real estate expropriated following parliament's decision. NOK 1.7 billion were used to purchase land, including the Air Force. It was the state that expropriated and bought all the land and remained land owner, while Oslo Lufthavn leases the ground from the state.[28] The first two years were used to demolish and rebuild the air station. This reduced the building area from 120,000 to 41,000 square metres (1,290,000 to 440,000 sq ft), but gave a more functional design.[29]

Construction of the new main airport started on 13 August 1994.[30] The western runway was already in place, and had been renovated by the Air Force in 1989. A new, eastern runway needed to be built. A hill at the airport was blown away, and the masses used to fill in where needed. The construction of the airport and railway required 13,000 man-years. 220 subcontractors were used, and working accidents were at a third of the national average, without any fatalities.[31] The last flights to Fornebu took place on 7 October 1998. That night, 300 people and 500 truckloads transported equipment from Fornebu to Gardermoen. Gardermoen opened on 8 October 1998.[32]

The airlines needed to build their own facilities at Gardermoen. SAS built a complex with 55,000 square metres (590,000 sq ft), including a technical base, cabin storage, garages and cargo terminals, for NOK 1.398 billion. This included a technical base for their fleet of Douglas DC-9 and McDonnell Douglas MD-80-aircraft for NOK 750 million. The cargo handling facility is 21,000 square metres (230,000 sq ft) and was built in cooperation with Posten Norge. SAS also built two lounges in the passenger terminal. Since Braathens had its technical base at Stavanger Airport, Sola, it used NOK 200 million to build facilities. This included a 9,000 square metres (97,000 sq ft) hangar for six aircraft for NOK 100 million.[33]

Parliament decided to build a high-speed airport rail link from Oslo to Gardermoen. The 64-kilometre (40 mi) Gardermoen Line connects Oslo Central Station (Oslo )to Gardermoen and onwards to Eidsvoll. This line was constructed for 210 kilometres per hour (130 mph) and allows the Flytoget train to operate from Oslo Central station to Gardermoen in nineteen minutes. Just like the airport, the railway was to be financed by the users. The Norwegian State Railways (NSB) established a subsidiary, NSB Gardermobanen, which would build and own the railway line, as well as operate the airport trains. The company would borrow money from the state, and repay with the profits from operation. During construction of the Romerike Tunnel, a leak was made that started draining the water from the lakes above.[34] The time and cost to repair the leaks meant that the whole railway line budget was exceeded, and the tunnel would not be taken into use until 1 August 1999. Since the rest of the railway was finished, two trains (instead of the intended six), operated using more time from the opening of the new airport.

The main road corridor northwards from Oslo to Gardermoen is European Route E6. The E6 was upgraded to six lanes north to Hvam, and to four lanes north to Gardermoen. The E6 runs about 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) east of the airport, so 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) of Norwegian National Road 35 was upgraded to four-lane motorway to connect the E6 to the airport. This connection cost NOK 1 billion. After the opening of the airport, National Road 35 was upgraded west of the airport as a two-lane toll road. Also Norwegian National Road 120 and Norwegian National Road 174 were upgraded.[35]

Opening and growth

The first new airline to start scheduled flights was Color Air operating Boeing 737-300 jets. The low-cost airline took advantage of the increased capacity that Gardermoen created to start competing with SAS and Braathens on the routes to Bergen, Trondheim and Ålesund. This lasted until October 1999, when Color Air filed for bankruptcy. During this time, all three airlines lost large amounts of money, mainly due to low cabin loads. To win the business market, all three wanted to have the most possible departures per day to other cities.

Gardermoen has had considerable problems with fog and freezing rain, and has several times had a complete close-down. This was also a problem at Fornebu, and reported to be at Hurum as well. On average, there is super cooled rain three times per month during the winter.[25] The use of deicing fluids is restricted since the area underneath the airport contains the Tandrum Delta, one of the country's largest uncontained quaternary aquifers (underground water systems).[36] On 14 December, 1998, a combination of freezing fog and supercooled rain caused glaze at Gardermoen. At least twenty aircraft engines were damaged by ice during take-off, and five aircraft needed to make precautionary landings with only one working engine.[25] On 18 January, 2006, an Infratek deicing system was set up, that uses infrared heat in large hangar tents. It was hoped that it could reduce chemical deicers by 90%, but the technique has proved unsuccessful.[37]

In 1999, Northwest Airlines briefly operated a flight between Oslo and Minneapolis/St. Paul, MN, United States, for several months, before the flight was cancelled due to poor load factors.[38][39] Northwest had previously served the airport in 1987 with nonstop flights operated with McDonnell Douglas DC-10-40 wide body jetliners several days a week to JFK, New York with continuing direct service to Memphis International Airport (MEM) and Minneapolis–Saint Paul International Airport (MSP).[40] In October 2001, the only remaining intercontinental flight, to Newark Airport (EWR), with Scandinavian Airlines (SAS) operated Boeing 767-300 aircraft, was discontinued, due to a slump in air travel following the 9/11. In 2004, Scandinavian Airlines and Continental Airlines (now United Airlines) resumed service on this route using Airbus A330 and Boeing 757-200 respectively. United Airlines suspended winter service on the route in 2015, then discontinued the service completely in 2017. Scandinavian Airlines also started a direct service from Oslo to Miami in 2016.[41]

Also in 1999, Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) became the first Asian airline to touchdown in Oslo, commencing its first flights to the city to and from Karachi, Lahore and Islamabad. The return flights had a stopover at Copenhagen Airport before continuing onward to Pakistan.[42]

Norwegian Air Shuttle launched flights to Bangkok, New York – JFK, Los Angeles, Fort Lauderdale, Oakland (San Francisco), and Orlando with Boeing 787 Dreamliner jetliners and Dubai, Agadir and Marrakech with Boeing 737-800 jets, and Thai Airways to Bangkok, Qatar Airways to Doha, Emirates to Dubai. In 2012, the airport opened a new 650-square-meter (7,000 sq ft) VIP terminal exclusively used for the royal family, the prime minister and foreign heads of state and government.[43]

Facilities

The airport covers an area of 13 square kilometres (5.0 sq mi) and is modeled partially on Hartsfield–Jackson Atlanta International Airport, with two parallel runways and a single terminal with two piers on a single line.[32][44] Oslo Airport is located 19 nautical miles (35 km; 22 mi) north-northeast of Oslo city centre.[4]

Terminal

The passenger terminal covers 265,000 square metres (2,850,000 sq ft).[32] The airport has 72 gates, of which 44 are bridge-connected and 28 are remote stands.[32] Domestic gates are located in the west and north pier (gates A, B, C), while gates for international flights are in the east and north pier (gates D, E), with gates for non-Schengen area flights at the end of the east pier (gates F).[45] Four gates near the end of the east pier are flexigates where doors can be opened or closed to switch between Schengen and non-Schengen flights.[46] EU controllers have been somewhat sceptical of the Schengen/non-Schengen flexigates, and there were a few incidents where the wrong doors were opened so that passengers who should have gone through the border control did not.[47] The new pier that extends northwards from the terminal was opened in 2017.[48] To compensate for the gates lost in the interim period, an extra pier south of and parallel to the west wing was constructed in 2012 for domestic flights. This "pier south" has eight gates that all lack jet bridges, and was intended for demolition after five years.[49] The extension gives a capacity of 32 million; in 2016, 25.7 million passengers used the airport.[50] The airport is "silent", so announcements for flights are only done in the immediate vicinity of the gate. There is a playground in both the domestic and international sections, and a quiet room in the domestic section. Medical personnel are stationed at the airport.[51]

Because of the airport's customs procedures for connecting passengers (the luggage has to be picked up, shown to customs and checked in when connecting from international to domestic flights), some transit passengers are now avoiding Oslo Airport and finding other routing options when possible. The process of clearing customs before connecting from an international to a domestic flight is not unique for Oslo Airport, as it is the same process used at international airports in the United States and some other countries.[52]

About half the airport operator's income is from retail revenue. There are twenty restaurants providing food or drink service, in addition to stores and other services including banks and post. In all, 8,000 square metres (86,000 sq ft) are used for restaurants, stores and non-aviation services.[50][53] The departure duty-free shop is 1,530 square metres (16,500 sq ft) and the largest in Europe. The shop is located in front of the international concourse, taking up a large part of the terminal's width.[54] The airport has attempted to funnel all passengers through the duty-free.[55] Signs that were to hinder passengers from walking outside the duty-free were in 2008 removed after criticism.[56][57] Arriving passengers have access to a smaller duty-free shop in the baggage claim area.

In addition to the main terminal, the airport operates its own VIP lounge for the Norwegian Royal Family, for members of the Norwegian government and members of foreign royal families and governments.[58] The GA-terminal, located on the west side of the airport, services GA-aircraft, executive jets and ambulance aircraft.[59] The cargo terminal is located just southwest of the main terminal and has 7 gates for cargo aircraft.[32] The airport is heated using district heating with a geothermal source. The airport uses 32.6 GWh/year for heating and 5.6 GWh/year for cooling. In addition, the airport uses 110 GWh/year of electricity.[60]

Art and architecture

Architects were Aviaplan, a joint venture between the agencies Nordic — Office of Architecture, Niels Torp, Skaarup & Jespersen and Hjellnes Cowi.[44] The main architect was Gudmund Stokke. The terminal building has a light, floating roof that results in simple construction. First the walls were erected, and a roof put on top. Afterwards internal facilities were added. The roof is held up by wooden reefers. The main construction materials are wood, metal and glass. The airlines were required to follow the same design rules for their buildings as the terminal.[61]

The main art on the landside of the airport is Alexis, consisting of six steel sculptures in stainless steel created by Per Inge Bjørlo. On the airside, Carin Wessel used 30,000 metres (98,000 ft) of thread to make the impression of clouds and webs, named Ad Astra. Anna Karin Rynander and Per-Olof Sandberg cooperated in making two installations: The Marathon Dancers, located in the baggage claim area, is a set of two electronic boards that show a dancing person. Sound Refreshment Station, of which six are located in the departure areas, are sound "showers" that make refreshing sounds when a person is immediately under them. Sidsel Westbø etched the glass walls. In the check-in area, there are small boxes under the floor with glass ceilings that contain curiosities. As well as the custom-made art, several existing sculptures and paintings were bought.[62] At the National Road 35 and European Route E6 junction, Vebjørn Sand built a 14-metre (46 ft) statue named the Kepler Star. It consists of two internally illuminated Kepler–Poinsot polyhedrons, appearing like a giant star in the sky after dark.

Runways and air traffic control

The airport has two parallel runways, aligned 01/19. The west runway 01L/19R is 3,600 by 45 metres (11,811 ft × 148 ft), while the east runway 01R/19L is 2,950 by 45 metres (9,678 ft × 148 ft).[4] Both have taxiways, allowing 80 air movements per hour.[32] The runways are equipped with CAT IIIA instrument landing system[63] and the airport is supervised by a 91-metre (299 ft) tall control tower.[50] Once departing aircraft are 15 kilometres (9 mi) away from the airport, responsibility is taken over by Oslo Air Traffic Control Center, which supervises the airspace with Haukåsen Radar. The airport has two ground radars, on the far sides of each of the runways. Both at the gates and along the taxiways, there is an automatic system of lights that guide the aircraft. On the tarmac, these are steered by the radar, while they are controlled by motion sensors at the gate.[64]

There are three deicing platforms.[65] Both fire stations each have three fire cars, and is part of the municipal fire department.[66] Meteorological services are operated by the Norwegian Meteorological Institute, which has 12 weather stations and 16 employees at the airport. This includes Norway's first aeronautic information service and a self-briefing room, in addition to briefings from professionals.[67] Restrictions on air movements apply overnight from 23:00 to 06:00, although permitted if landing from and taking off to the north.[68]

Air station

The Royal Norwegian Air Force has an air base at Gardermoen, located at the north side of the passenger terminal at Oslo Airport. The base dates from 1994 and houses the 335-Squadron that operates three Lockheed C-130 Hercules transport planes. The airbase also handles nearly all military freight going abroad. The Air Force has a compact 41,000 square metres (440,000 sq ft) building space, with a maximum walking distance of 400 metres (1,300 ft). The station is built so that it can quickly be expanded if necessary, without having to claim areas used by the civilian section. The military also use the civilian terminals for their passenger transport needs, and send 200,000 people with chartered and scheduled flights from the main terminal each year.[69] The airforce station serves as the main entering point for VIPs and officials going to Norway.

Organisation

The airport is owned by Oslo Lufthavn AS, a limited company wholly owned by Avinor, a state-owned company responsible for operating 46 Norwegian airports. In 2010, Oslo Lufthavn had a revenue of NOK 3,693 million, giving an income of NOK 1,124 million before tax. The profit from the airport is largely paid to Avinor, who uses it to cross-subsidise operating deficits from smaller primary and regional airport throughout the country. At the end of 2010, Oslo Lufthavn had 439 employees.[70]

The company has a subsidiary, Oslo Lufthavn Eiendom AS, which is responsible for developing commercial real estate around the airport. It owns one airport hotel run by the Radisson Blu chain, the office building and conference center Flyporten, which along with the hotel features 60 conference rooms, and the employee parking lot. A second hotel, Park Inn, was opened in September 2010.

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

The three main airlines operating Oslo Airport as a hub are Scandinavian Airlines, Norwegian Air Shuttle and Widerøe. Oslo Airport's functions, along with the other two Scandinavian capital airports, as a hub for SAS, while it is the main hub for Norwegian. In Southern Norway, the Ministry of Transport and Communications subsidizes the services to eight regional airports based on four-year public service obligations.

The following airlines operate regular scheduled and charter services to and from Gardermoen:[71]

Cargo

Statistics

Oslo Airport has a catchment area of 2.5 million people, including most of Eastern Norway and 0.3 million people in Sweden.[94] In 2017, Oslo Airport served 27,482,315 passengers, 181,265 tonnes (178,402 long tons; 199,810 short tons) of cargo and 242,555 aircraft movements. Within Europe in 2017, Oslo Airport ranked as the nineteenth-busiest. It is the second-busiest airport in the Nordic countries, after Copenhagen Airport. The busiest route is to Trondheim, with over 2 million passengers. Along with the domestic routes to Bergen and Stavanger, and the international routes to Copenhagen and Stockholm, Oslo Airport served five of the twenty-five busiest routes in the EEA, all with more than one million passengers.[95]

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | % Change |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 19,091,036 | |

| 2011 | 21,103,623 | |

| 2012 | 22,080,433 | |

| 2013 | 22,956,540 | |

| 2014 | 24,269,235 | |

| 2015 | 24,678,195 | |

| 2016 | 25,787,691 | |

| 2017 | 27,482,315 | |

| 2018 | 28,516,220 | |

| 2019 | 28,592,619 |

The following is a list of the 20 busiest routes to and from Gardermoen during 2017.[97]

| Rank | City / Country | Airport(s) | Passengers | Change 2016–2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Trondheim | 2,092,000 | ||

| 2 | Bergen | 1,987,000 | ||

| 3 | Stavanger | 1,603,000 | ||

| 4 | Copenhagen | 1,558,000 | ||

| 5 | Arlanda | 1,420,000 | ||

| 6 | Gatwick Heathrow Stansted Luton | 1,399,000 | ||

| 7 | Tromsø | 1,235,000 | ||

| 8 | Bodø | 830,000 | ||

| 9 | Schiphol | 708,000 | ||

| 10 | Ålesund | 617,000 | ||

| 11 | Harstad / Narvik | 589,000 | ||

| 12 | Kristiansand | 533,000 | ||

| 13 | Frankfurt | 526,000 | ||

| 14 | Helsinki | 506,000 | ||

| 15 | Haugesund | 480,000 | ||

| 16 | Charles de Gaulle Orly | 443,000 | ||

| 17 | Munich | 394,000 | ||

| 18 | Alicante | 362,000 | ||

| 19 | Molde | 357,000 | ||

| 20 | Schönefeld Tegel | 349,000 |

| Rank | City / Country | Airport(s) | Passengers | Change 2016–2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New York–JFK Newark | 281,000 | ||

| 2 | Suvarnabhumi | 243,000 | ||

| 3 | Dubai–International | 193,000 | ||

| 4 | Doha | 136,000 | ||

| 5 | Los Angeles | 58,000 | ||

| 6 | Miami | 56,000 | ||

| 7 | Fort Lauderdale | 55,000 | ||

| 8 | Boston | 35,000 | ||

| 9 | Oakland/San Francisco | 34,000 | ||

| 10 | Orlando–MCO | 29,000 |

Ground transportation

Situated about 47 kilometres (29 mi) from the city center,[99] Oslo Airport offers extensive public transporting services. The airport has one of the world's highest levels of public transport usage, with a share of nearly 70%.[5]

The 64 kilometres (40 mi) Gardermoen Line opened the same day as the airport, and runs in a tunnel below the airport facilities, where Gardermoen Station is located below the terminal. The Flytoget airport express train operates to Oslo Central Station six times per hour in 19 to 22 minutes, with three services continuing onwards via five intermediate stations to Drammen Station. (On Saturdays and Sundays, the frequency is three times per hour.)[100] The Airport Express Train has a 34% ground transport share.[101]

Vy also operates from the airport, both a commuter train service to Eidsvoll and Kongsberg, and a regional service north to Innlandet and south to Vestfold og Telemark. Both offer services to Oslo, and the latter allows direct service to Sandefjord Airport, Torp. Five daily express trains operated by SJ Norge to Trondheim stop at the airport, including one night train.[102]

The Oslo Airport Express Coach serves the airport, from Oslo, Fredrikstad, Ski and Gjøvik.[103] In addition, most express buses from other parts of Norway stop at the airport. The local transport authority, Ruter, operates a number of services to Oslo Airport from nearby places.

The airport is located 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) from European Route E16, and 6 kilometres (3.7 mi) from the European Route E6 and connect to them as a four-lane motorway. The E6 runs south with four lanes to Oslo, and northwards with four lanes towards Oppland, Hedmark and Central Norway. E16 connects with two lanes westward towards Buskerud and eastward towards Sweden.[35] All these directions are toll roads, at least in part. There are 11,400 parking spaces at the airport,[104] as well as taxi stands and rental car facilities.

Taxi

There are several companies offering services at Oslo Airport. In order to check companies, rates and book a taxi, the passenger must go to the information desk at the Arrivals Hall of the airport.[105] The taxi rank is located just outside the arrivals hall.

Plans

Oslo Airport has experienced rapid increases in passenger numbers during the last decade, already exceeding its original capacity limit of 17 million passengers. As a result, the Norwegian Air Transport Authority, Avinor, approved plans on 19 January, 2011, for an expansion of OSL with Terminal 2 (North Pier). Finished in Spring 2017, the expansion involved construction of a new pier located directly after security checkpoint with eleven new air bridges, six remote stands, a new arrivals- and departure-hall and a new baggage handling system. A total of 117,000 square meters were added, resulting a total of 265,000 square meters today. OSL can now handle 32 million passengers annually.[106] Yet, before the North Pier was finished, OSL have invested further plans to expand the international terminal with six new wide-body airliner gates for more direct flights to destinations outside of Europe. The expansion is set to begin in 2017 and will be finished between 2019 and 2021[107] Once the intercontinental expansion is finished, the airport will be able to accommodate the double-decker Airbus A380.[108] This would also advance point-to-point flying and fix the major issue where Norwegians are traveling to larger hub-and-spoke airports in Europe in order to reach their final destination, because OSL (both the market and airport's size) is too small to handle a global flight network.[109] Another phase will be added later on to bring the total capacity to 35 million passengers annually through the T2-project.[110][111] If passenger traffic continues to grow and if the capacity will be surpassed beyond the capabilities, OSL and Avinor will call out for a master phase (as situated in the Master Plan 2012–2050), including extension of the North Pier by another 100 meters, adding a third runway with a free-standing pier between it and the existing Eastern runway, as well as a new terminal to the southeast area of the current international terminal (by where Park Inn is located).[112]

The Government of Oslo has debated if a third runway in the future will be reliable. If they approve, the runway will not be finished until 2030 at the earliest. Avinor has discovered the existing runway capacity will be saturated by 2030, but critics have pointed out that larger hubs as Heathrow in London only operates with two runways. However, such airports tend to suffer of major delays and chaos at their schedules. Oslo had 253,542 movements against 474,087 at Heathrow in 2017. Former Minister of Transport, Liv Signe Navarsete (Center), has stated that spreading the traffic between the two airports (RYG is closed on permanent basis) will result in inconvenience for passengers and a massive need for inter-airport ground transportation, but has announced she is opposed to a third runway.[113] Avinor is facing large costs of extending short runways in rural locations or replacing such airports during the 2020s decade, so a third runway at Oslo is less prioritized. However, as of December 2017, construction of a nearby city directly to the east of OSL has been officially approved, nicknamed "the Gate to Europe", in which a third runway and a third terminal are part of the project.[114]

Norwegian CEO Bjørn Kjos has announced that the airline has ambitions to evolve Gardermoen into a major global hub between North America and South Asia. Kjos stated; "We could have received tons of traffic from all around the world. Oslo could have been one of the largest hubs in Europe, and could have competed against the large ones in the Middle East" (DXB and DOH). He guarantees the transatlantic routes will be significantly shorter via Northern Europe, which will lead to increased efficiency and satisfaction for the travelers and for the economy. Norwegian is currently disallowed to fly direct over Russian territory by their Air Traffic Authorities, meaning that negotiation is the only solution.[115]

The name

Gardermoen is a compound of the farm name Garder and the finite form of mo 'moor; drill ground' (thus 'the moor belonging to the farm Garder'). The farm is first mentioned in 1328 (Garðar), and the name is the plural of Norse garðr 'fence'. The meaning is probably 'enclosure; fenced fields'.

Delays in 2012

According to EUROCONTROL, the "European Organisation for the Safety of Air Navigation", Gardermoen had the most delays per flight of all airports in Europe in July 2012. As a consequence of the delays, which apparently were caused by a lack of air traffic controllers, several airlines are demanding NOK 100 million in compensation from Avinor. The head of Avinor said that the agency may pay compensation to the airlines, also saying that "they did not get a good enough product last summer".[116]

See also

References

Notes

- "Traffic Statistics – Avinor". avinor.no. Retrieved 22 January 2018.

- "Flytrafikkstatistikk desember" (in Norwegian). Avinor. January 2013. Archived from the original on 26 February 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2013.

- "Flight timetables". Oslo Lufthavn. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- "ENGM – Oslo" (PDF). AIP Norge/Norway. Avinor. 31 May 2012. AD 2 ENGM. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- Avinor. "Rekordhøy kollektivandel i tilbringertransporten til Oslo Lufthavn" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 23 August 2017. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- "Om prosjektet (Norwegian)". Oslo Lufthavn. Retrieved 16 April 2011.

- Bredal, 1998: 100

- Bredal, 1998: 13

- Bredal, 1998: 14–16

- Wisting, 1989: 63–65

- Bredal, 1998: 16

- Wisting, 1989: 13–20

- Wisting, 1989: 30

- Wisting, 1989: 35–41

- Wisting, 1989: 58–61

- Bredal, 1998: 17–18

- Bredal, 1998: 14

- Bredal, 1998: 19

- Bredal, 1998: 17–19

- Wisting, 1989: 80–83

- Bredal, 1998: 23–26

- Bredal, 1998: 28–29

- The Norwegian Institute of Journalism. "SKUP Prize 1999" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 24 March 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Enghaug, Pål; et al. "Wiborg and the Gardermoen weather report" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 6 August 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- whistleblowers.dk. "The political plotting of an airport". Archived from the original on 8 October 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- California Aviation Alliance. "Norwegian airport probe says court of impeachment must be considered". Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Bredal, 1998: 39

- Bredal, 1998: 83–84

- Bredal, 1998: 104

- Bredal, 1998: 45

- Bredal, 53–65

- "About Oslo Airport – Avinor". avinor.no. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Bredal, 170–173

- Bredal, 1998: 137–141

- Bredal, 1998: 141–146

- Muhammad, Nuha; Pedersen, Tor. "A CHARACTERIZATION OF THE DISTAL PART OF TRANDUM DELTA, SOUTHERN NORWAY, BY GROUND PENETRATING RADAR" (PDF). Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Travelnews. "Infrared fiasco at Gardermoen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 25 February 2007.

- Lillesund, Geir (30 March 1999). "Bare Braathens kutter ruter i sommerprogrammet" (in Norwegian). Norwegian News Agency.

- "Gardermoen er flyselskapenes mareritt". Dagbladet.no (in Norwegian). 31 August 1999.

- http://www.departedflights.com, 7 September 1979 Northwest Airlines system timetable

- "SAS is opening two new routes from Miami - SAS". www.sasgroup.net. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- "History of PIA: Historic Firsts".

- "Skuddsikker terminal for de viktige". Dagens Næringsliv (in Norwegian). 31 January 2012. Archived from the original on 1 February 2012. Retrieved 31 January 2012.

- Bredal, 1998:45

- "Map – Avinor". avinor.no. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- "Oslo Lufthavn" (PDF). avinor.no. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- "Polakker ankom uten kontroll" (in Norwegian). Verdens Gang. 18 July 2001. Retrieved 10 June 2011.

- "New Avinor Oslo Airport officially open". Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- Fonbæk, Dag (31 August 2012). "Hurra, nå slipper du å busse til flyet på Gardermoen!" (in Norwegian). VG. Retrieved 15 June 2014.

- "Facts and figures". Oslo Lufthavn AS. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- Bredal, 1998: 188–190

- "Customs May Be Simplified" (in Norwegian).

- "Shops and dining". Oslo Lufthavn AS. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- Von Hanno Brockfield, Johan (19 April 2009) [12 May 2005]. "Her åpner Europas største tax-free" (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 4 June 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Mikalsen, Knut-Erik (6 September 2008). "Her går du rett i taxfree-fella" (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 26 October 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Mikalsen, Knut-Erik (8 September 2008). "Taxfree-fellen blir fjernet" (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- Mikalsen, Knut-Erik (28 September 2008). "Taxfree-fellen er fjernet" (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. Archived from the original on 1 February 2009. Retrieved 26 May 2009.

- "Skuddsikker terminal for de viktige" (in Norwegian). Dagens næringsliv. 31 January 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- Bredal, 1998: 194–195

- Bredal, 1998: 110–111

- Bredal, 1998: 45–50

- Bredal, 1998: 131–136

- Bredal, 1998: 175

- Bredal, 1998: 179–181

- "De-icing areas. Oslo Airport" (PDF). AIP Norge/Norway. Avinor. 17 November 2011. p. AD 2 ENGM 2–6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 June 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2012.

- "Brann og redning – en viktig medspiller i nærmiljøet (Norwegian)". Oslo Lufthavn AS. Retrieved 17 April 2012.

- Bredal, 1998: 157–160

- Bredal, 1998: 181

- Bredal, 1998: 103

- "Annual Report 2010" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Oslo Lufthavn. 2011. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- avinor.no - Direct flights from Oslo Airport retrieved 6 January 2021

- "Air Serbia launching new route this summer". www.exyuaviation.com.

- airBaltic expands Tallinn network in W18 Routesonline. 2 February 2018.

- "Saker – Oslo lufthavn". Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/289062/corendon-airlines-s20-network-expansion/

- LOT resumes Oslo service in March 2018 Routesonline. 11 October 2017.

- "Only Flight". apollo.no.

- "Flight". Ving.no.

- sunexpress.com - Route map retrieved 17 January 2021

- https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/291544/tap-air-portugal-june-august-2020-operations-as-of-31may20/

- "Flight". apollo.no.

- https://wizzair.com/

- https://www.hermesairports.com/corporate/press-office/media-releases/wizz-air-adds-3-destinations-to-its-larnaka-network

- "AirBridge Cargo makes Avinor Oslo Airport the Scandinavian hub for air cargo". Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- "Saker – Oslo lufthavn". Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Cargolux launches cargo route at Avinor Oslo Airport". Archived from the original on 27 October 2017. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- skychain.emirates.com - View Schedule retrieved 3 October 2020

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 18 October 2018. Retrieved 18 October 2018.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- cargo.koreanair.com - Flight Operation Status retrieved 3 October 2020

- [https://www.qrcargo.com/weeklySchedules qrcargo.com - Schedules retrieved 3 October 2020

- "Silkway west airlines goes for salmon – new freighter airline to Avinor Oslo airport". NTB, The Avinor Group. Retrieved 26 September 2019.

- turkishcargo.com - Flight Schedule retrieved 3 October 2020

- westatlantic.eu - Air Cargo Destinations retrieved 3 October 2020

- "Market". Oslo Lufthavn. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- "Jernbane- og trafikkonsept for Sør- og Midt-Norge" (PDF) (in Norwegian). Norsk Bane and Deutsche Bahn. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- Press-release. "Avinor". Mynewsdesk.

- "Traffic Statistics". avinor.no. AVINOR. Retrieved 8 May 2018.

- "Trafikkstatistikk – Avinor". avinor.no. Retrieved 8 October 2018.

- "Administration". Oslo Lufthavn. Archived from the original on 24 January 2010. Retrieved 19 January 2010.

- Flytoget. "Om Flytoget" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 9 January 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- Oslo Lufthavn (1 September 2007). "Oslo Airport – Highest figures for use of public transport in Europe".

- Avinor. "Tog" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- Oslo Airport Express Coach. "Velkommen til Flybussen i Oslo!" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 24 February 2007. Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- Avinor. "Parkering" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- "Oslo Airport Transport". www.oslo-airport.com. Retrieved 6 October 2016.

- "The new Oslo Airport 2017 - Avinor". avinor.no. Retrieved 10 May 2020.

- Avinor. "Avinor Oslo Airport 1st of July 2016 Update" (PDF).

- Aftenposten (29 June 2015). "Gardermoen utvider for å ta imot verdens største passasjerfly" (in Norwegian).

- Aftenposten (11 February 2014). "Vil ha 20 nye interkontinentale ruter til Oslo" (in Norwegian).

- Airport-Business (8 October 2014). "1.7 billion pounds expansion of Oslo Airport will boost capacity and future-proof growth".

- Fjernvarme. "Oslo Lufthavn T2-Prosjektet" (PDF) (in Norwegian).

- Tu (27 April 2016). "Bli med i nye Oslo Lufthavn" (in Norwegian).

- Dagens Næringsliv. "Navarsete satser på Gardermoen" (in Norwegian). Retrieved 24 February 2007.

- "Oslo Airport City approved" (in Norwegian). 4 December 2017.

- "Bjørn Kjos vil gjøre Oslo til gigantflyplass" (in Norwegian). 9 February 2017.

- "Airlines demand compensation for air traffic control delays". Retrieved 10 May 2015.

External links

Media related to Oslo Airport, Gardermoen at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Oslo Airport, Gardermoen at Wikimedia Commons Gardermoen travel guide from Wikivoyage

Gardermoen travel guide from Wikivoyage- Official site

- ENGM – OSL. AIP and charts from Avinor.

- Aeronautical chart and airport information for ENGM at SkyVector

- Current weather for ENGM at NOAA/NWS

- Accident history for OSL at Aviation Safety Network