Newark Liberty International Airport

Newark Liberty International Airport (IATA: EWR, ICAO: KEWR, FAA LID: EWR), originally Newark Metropolitan Airport and later Newark International Airport, is an international airport straddling the boundary between the cities of Newark in Essex County and Elizabeth in Union County, New Jersey. It is one of the major airports of the New York metropolitan area.[3] The airport is currently owned jointly by the cities of Elizabeth and Newark and leased to and operated by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[4]

Newark Liberty International Airport | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Summary | |||||||||||||||||||

| Airport type | Public | ||||||||||||||||||

| Owner | Newark and Elizabeth, New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||

| Operator | Port Authority of New York and New Jersey | ||||||||||||||||||

| Serves | New York metropolitan area | ||||||||||||||||||

| Location | Newark and Elizabeth, New Jersey, U.S. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Opened | October 1, 1928 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hub for | |||||||||||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 17.4 ft / 5 m | ||||||||||||||||||

| Coordinates | 40°41′33″N 074°10′07″W | ||||||||||||||||||

| Website | newarkairport.com | ||||||||||||||||||

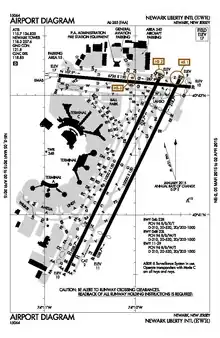

| Maps | |||||||||||||||||||

FAA diagram | |||||||||||||||||||

EWR Location near New York City  EWR Location in New Jersey  EWR Location in the United States  EWR Location in North America | |||||||||||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Helipads | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Statistics (2019) | |||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Newark Airport is located 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Downtown Newark, and 9 miles (14 km) west-southwest of the borough of Manhattan. It is one of three major airports serving the New York metropolitan area; the others are John F. Kennedy International Airport and LaGuardia Airport, which are also operated by the Port Authority.

Sandwiched between Interstate 95 and Interstate 78 (both components of the New Jersey Turnpike), as well as U.S. Routes 1 and 9 and has junctions of U.S. Route 22, NJ-81 and the Garden State Parkway. The airport handles almost as many flights as John F. Kennedy International Airport (JFK), despite being 40 percent of JFK's land size. The City of Newark built the airport on 68 acres (28 ha) of marshland in 1928 and the Army Air Corps operated the facility during World War II. After the Port Authority took it over in 1948, an instrument runway, a terminal building, a control tower and an air cargo center were added. The airport's original 1935 central terminal building is a National Historic Landmark. EWR employs more than 24,000 people.[5]

In 2017, EWR was the sixth busiest airport in the United States by international passenger traffic and fifteenth busiest airport in the country. It served 43,393,499 passengers in 2017, which made EWR the forty-third busiest airport in the world by passenger traffic. In 2019, the airport saw 46,336,452 passengers, the most in its history.

Newark serves 50 carriers and is the third-largest hub for United Airlines, the airport's largest tenant (operating in all three of Newark's terminals),[6] and FedEx Express, its second-largest tenant (operating in three buildings on two million square feet of airport property).[7] During the 12-month period ending in July 2014, over 68% of all passengers at the airport were carried by United Airlines.[8]

History

Early years

Newark Metropolitan Airport opened on October 1, 1928, on 68 acres (28 ha) of reclaimed land along the Passaic River,[5] the first major airport serving passengers in the New York metro area.[9] The Art Deco style Newark Metropolitan Airport Administration Building, adorned with murals by Arshile Gorky,[10] was built in 1934 and dedicated by Amelia Earhart in 1935.[11] It served as the terminal until the opening of the North Terminal in 1953. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1979 and is now a museum and Port Authority Police headquarters.

Newark was the busiest commercial airport in the world until LaGuardia Airport opened in December 1939; the March 1939 Official Aviation Guide shows 61 weekday departures on five airlines, but by mid-1940 passenger airlines had all left Newark.[12][13]

During World War II the field was closed to commercial aviation while it was taken over by the United States Army for logistics operations. In 1945 captured German aircraft brought from Europe on HMS Reaper for evaluation under Operation Lusty were off-loaded at Newark AAF and then flown or shipped to Freeman Field, Indiana or Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland. The airlines returned to Newark in February 1946. In 1948, the city of Newark leased the airport to the Port of New York Authority (now the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey). As part of the deal, the Port Authority took operational control of the airport and began investing heavily in capital improvements, including new hangars, a new terminal and runway 4/22.

The February 1947 C&GS diagram shows 5,940-foot (1,811 m) runway 1, 7,900-foot (2,408 m) runway 6 and 7,100-foot (2,164 m) runway 10.

On December 16, 1951, a Miami Airlines C-46 bound for Tampa lost a cylinder on takeoff from runway 28 and crashed in Elizabeth killing 56.[14] On January 22, 1952, an American Airlines CV-240 crashed in Elizabeth while on approach to Runway 6, killing all 23 aboard and seven on the ground.[15] On February 11, 1952, a National DC-6 crashed in Elizabeth after takeoff from runway 24, killing 29 of 63 on board and four on the ground.[16][17] Inevitably, the airport was closed for some months; airline traffic resumed later in the year, but the airport's continued unpopularity and the New York area's growing air traffic led to searches for new airport sites. A proposal to build a new airport at what is now the Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge was defeated by local opposition.

The April 1957 Official Airline Guide showed 144 weekday passenger fixed-wing departures from Newark: 40 Eastern, 19 Capital, 16 American, 14 United, 14 Mohawk, 13 Allegheny, 11 TWA, 8 National, 5 Delta and 4 Braniff. National had a nonstop to Miami, Eastern had nonstops to Miami, New Orleans and Houston, Braniff had a nonstop DC-7C to Dallas and TWA flew nonstop to St Louis; no other nonstops to points west of St. Louis and no international nonstops.[18] (Eastern started a nonstop to Montreal in 1958, probably Newark's first scheduled international nonstop since 1939, though Eastern had nonstops to San Juan in 1951.) Jet airliners arrived in 1961. In 1964, American and TWA started flying nonstop to California, although Newark's longest runway was 7,000 ft (2,100 m) until 1970. TWA's 707 nonstop to Heathrow in 1978 was probably Newark's first trans-Atlantic nonstop.

Late 20th century

Through the early 1970s, Newark had a single terminal building located on the north side of the field, by what is now Interstate 78.[19] In the 1970s the airport became Newark International Airport. Present Terminals A and B opened in 1973, although some charter and international flights requiring customs clearance remained at the North Terminal. The main building of Terminal C was completed at the same time, but only metal framing work was completed for the terminal's satellites. It lay dormant until the mid-1980s, when for a brief time the west third of the terminal was equipped for international arrivals and used for some People Express transcontinental flights. Terminal C was finally completed and opened in June 1988.

Underutilized in the 1970s, Newark expanded dramatically in the 1980s. People Express struck a deal with the Port Authority to use the North Terminal as its air terminal and corporate office in 1981 and began operations at Newark that April. It grew quickly, increasing Newark's traffic through the 1980s.[20] Virgin Atlantic began service between Newark and London in 1984, challenging JFK's status as New York's international gateway (but Virgin Atlantic now has more flights at JFK than at Newark). Federal Express (now known as FedEx Express) opened its second hub at the airport in 1986.[7] When People Express merged into Continental in 1987, operations (including corporate office operations) at the North Terminal were reduced and the building was demolished to make way for cargo facilities in the early 1990s. This merger started Continental's and later United Airlines', dominance at Newark Airport.

In late 1996 the monorail opened, connecting the three terminals, the overflow parking lots and garages, and the rental car facilities. A new International Arrivals Facility also opened in Terminal B that year.[9] The monorail was expanded to the new Newark Airport train station on Amtrak's Northeast Corridor line in 2001 and was renamed AirTrain Newark.

21st century

After the hijacking and crash of United Airlines Flight 93 in the September 11 attacks in 2001 while en route from Newark to San Francisco, the airport's name was changed from Newark International Airport to Newark Liberty International Airport in 2002. This name was chosen over the initial proposal, Liberty International Airport at Newark, and pays tribute to the victims of the September 11 attacks and to the landmark Statue of Liberty, lying just 7 miles (11 km) east of the airport.[21][22]

A modern control tower was built in 2002 and opened in 2003. It is the fourth and tallest tower in the airport's history, standing 325 feet (99 m) over the main parking lot.[9] In 2004, Singapore Airlines began the world's longest non-stop scheduled airline route to Newark from Singapore. The service ended on November 23, 2013,[23] and resumed on 11 October 2018,[24] though was suspended on March 25, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[25]

Continental Airlines (now merged with United Airlines) began flying from Newark to Beijing on June 15, 2005, and to Delhi on November 1, 2005. The airline soon started flights to Mumbai. On July 16, 2007, Continental announced it would seek government approval for nonstop flights between Newark and Shanghai in 2009. Continental began flights to Shanghai from Newark on March 25, 2009, using Boeing 777-200ER aircraft. Newark was the only New York area airport used by Philippine Airlines (PAL), until financial problems in the late 1990s caused it to terminate this service. In March 2015, PAL resumed service to the New York metropolitan area routing to JFK Airport, and will not return to Newark, following the removal of the Philippines from the air safety blacklist of the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).[26] In October 2015, Singapore Airlines announced intentions to resume direct nonstop service between Newark and its main hub at Singapore Changi Airport. For a time, the dates were not yet announced, but eventually the Airbus A350-900ULR was chosen and is used on the flights in 2018.[27][28] On May 30, 2018, Singapore Airlines officially announced that nonstop service between Newark and Singapore resumed on October 11, 2018 using the Airbus A350-900ULR. Singapore Airlines Flights 21 and 22 once again claimed their title as the world's longest non-stop scheduled airline flights.[29]

In June 2008 flight caps were put in place to restrict the number of flights to 81 per hour. The flight caps, in effect until 2009, were intended to be a short-term solution to Newark's congestion. The FAA has since embarked on a seven-year-long project to reduce congestion in all three New York area airports and the surrounding flight paths.[30]

Newark is a major hub for United Airlines (Continental Airlines before the 2010–12 merger). United has its Global Gateway at Terminal C, having completed a major expansion project that included a new, third concourse and a new Federal Inspection Services facility. With its Newark hub, United has the most service of any airline in the New York area. On March 6, 2014, United opened a new 132,000-square-foot (12,300 m2), $25 million hangar on a 3-acre (1.2 ha) parcel to accommodate United's wide body aircraft during maintenance.[31] In 2015, the airline announced plans to leave JFK altogether and streamline its transcontinental operations at Newark.[32] On July 7, 2016, the United States Department of Transportation announced that Newark was one of ten cities to first operate flights to José Martí International Airport in Havana, Cuba.[33]

As of 2012, United carried 71% of the airport's passengers. The two next-busiest airlines, Delta Air Lines and JetBlue, each had less than 5%.[34]

In 2016, the Port Authority approved and announced a redevelopment plan to replace Terminal A, set to fully open in 2022.[35] A $2.7 billion investment, Terminal One is expected to increase passenger flow and gate flexibility between airlines, and would also be accompanied by a replacement for the AirTrain Newark monorail system, scheduled for completion in 2024.[35]

Facilities

.jpg.webp)

Runways

The airport covers 2,027 acres (820 ha) and has three runways and one helipad:[37]

- 4L/22R: 11,000 by 150 feet (3,353 m × 46 m), asphalt/concrete, grooved

- 4R/22L: 10,000 by 150 feet (3,048 m × 46 m), asphalt, grooved

- 11/29: 6,726 by 150 feet (2,050 m × 46 m), asphalt, grooved

- Helipad H1: 54 by 54 feet (16 m × 16 m), asphalt

Runway 11/29 is one of the three runways built during World War II. In 1952 Runways 1/19 and 6/24 were closed and a new Runway 4/22 (now 4R/22L) opened at a length of 7,000 ft (2,100 m). After 1970 this runway was extended to 9,800 feet (3,000 m), shortened for a while to 9,300 ft (2,800 m) and finally reached its present length by 2000. Runway 4L/22R opened in 1970 at a length of 8,200 ft (2,500 m) and was extended to its current length by 2000.

All approaches except Runway 29 have Instrument Landing Systems and Runway 4R is certified for Category III approaches. Runway 22L had been upgraded to CAT III approach capability.[30]

Runway 4L/22R is primarily used for takeoffs while 4R/22L is primarily used for landings and 11/29 is used by smaller aircraft or when there are strong crosswinds on the two main runways. Newark's parallel runways (4L and 4R) are 950 feet (290 m) apart, the fourth smallest separation of major airports in the U.S., after San Francisco International Airport, Los Angeles International Airport and Seattle–Tacoma International Airport.

Unlike the other two major New York-area airports, JFK and LaGuardia, which are located directly next to large bodies of water (Jamaica Bay and the East River, respectively) and whose runways extend at least partially out into them, Newark Liberty, while located just across Interstate 95 from Newark Bay and not far from the Hudson River, does not directly front upon either body of water, so the airport and its runways are completely land-locked.

All of Newark's runways have displaced thresholds. Runways 4L/22R and 4R/22L have long displaced thresholds and often passenger aircraft will take off just at the threshold of the runway.

Terminals

Across the airport's three terminals, there are 121 gates: Terminal A has 29 gates, Terminal B has 24 gates, and Terminal C has 68 gates.[38]

Each terminal has three concourses: Terminal A, for instance, is divided into concourses A1, A2 and A3. Gate numbering starts in Terminal A with Gate 10 and ends in Terminal C with Gate 139. Wayfinding signage throughout the terminals was designed by Paul Mijksenaar, who also designed signage for LaGuardia and JFK Airports.[39]

Terminal A

Terminal A and Terminal B were both completed in 1973 and have four levels. Terminal A is operated by EWR Terminal One LLC, part of Flughafen München GmbH. Terminal A handles only domestic and Canadian flights served by JetBlue (including flights to the Caribbean), Air Canada, Air Canada Express, Alaska Airlines, American Airlines, American Eagle; and some United Express (i.e., ultra-short haul) flights.[40][41]

In Terminal A, ticket counters are on the top floor, baggage carousels are on the second floor, and parking is on the first floor. There is one United Club in Terminal A's second concourse. Gates and shops are on the third floor. Terminal A is the only terminal that has no immigration facilities; flights arriving from other countries cannot use Terminal A (except countries with U.S. customs preclearance), although some departing international flights use the terminal.

Terminal B

Terminal A and Terminal B were both completed in 1973 and have four levels. Terminal B is the only passenger terminal directly operated by the Port Authority. Terminal B exclusively handles foreign carriers; and also handles flights from the Caribbean through JetBlue, other carriers, such as Delta Airlines, Delta Connection, Sun Country, Elite Airways, Allegiant Air, Frontier Airlines and Spirit Airlines flights, and some of United's international arrivals.[41]

In Terminal B, ticket counters are on the top floor, except for the second-floor Aer Lingus, Frontier Airlines, Delta Air Lines and Icelandair counters and first-floor British Airways, Level, and Spirit Airlines. Baggage carousels are on the first floor for domestic arrivals and on the second floor for international arrivals. Terminal B also has an international arrivals lounge on the second floor. Gates and shops are on the third floor.

In 2008, Terminal B was renovated to increase capacity for departing passengers and passenger comfort. The renovations included expanding and updating the ticketing areas, building a new departure level for domestic flights and building a new arrivals hall.[42] In January 2012, Port Authority executive director Patrick Foye said $350 million would be spent on Terminal B, addressing complaints by passengers that they cannot move freely.[43] Further developments were made to Terminal B when the Port Authority installed new LED fixtures in 2014. The LED fixtures developed by Sensity Systems, use wireless network capabilities to collect and feed data into the software that can spot long lines, recognize license plates, and identify suspicious activity and alert the appropriate staff.[44]

Terminal C

Terminal C, designed by Grad Associates[45] was completed in 1988. Terminal C is exclusively operated by and for United Airlines and its regional carrier United Express for their global hub at EWR. The terminal has two ticketing levels, one for international check-in and one for domestic check-in. The main terminal building for Terminal C was built alongside Terminals A and B in the 1970s, but lay dormant until People Express Airlines took it over as a replacement for the former North Terminal when the airline's hub there outgrew the old facility. Upon opening, Terminal C had 41 gates, one departures level, one arrivals level, and an underground parking garage.

From 1998 to 2003, Terminal C was rebuilt and expanded in a $1.2 billion program known as the Continental Airlines Global Gateway Project.[46][47] The project, which was designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill,[46] doubled the available space for outbound travelers as the former baggage claim/arrivals hall was remodeled and turned into a second departures level. Probably most significant was the addition of International Concourse C-3, a spacious and airy new facility with capacity for a maximum of 19 narrowbody aircraft (or 12 widebody planes). Completion of this new concourse increased Terminal C's mainline jet gates to 57. Concomitant with Concourse C-3 is a new international arrivals facility. Also included in the project: a 3,400-space parking garage constructed in front of the terminal, a new airside corridor connecting Concourses C-1, C-2 and C-3, a new President's Club — now called United Polaris Lounge — for international Polaris Business and Polaris First flights between C-2 and C-3, and all-new baggage processing facilities, including reconstruction of the former underground parking area into a new baggage claim and arrivals hall.

The gates as well as food and shopping outlets are all located on a mezzanine level between the two check-in floors. Terminal C has multiple gates that can handle wide-body aircraft and narrow body aircraft. Gates C123 and C138 have two jet bridges, often used for Boeing 787 Dreamliner and Boeing 777 aircraft. During peak hours between 4-9 p.m., all gates are full and completely scheduled. During this time, gate availability often becomes scarce leading to delays for arriving and departing aircraft. When departing flights don't have a gate due to their wingspan, United will often put the flight at a smaller gate for the time during the delay, then move the flight to a wide-body gate once it becomes available.

In November 2014, airport amenity manager OTG announced a new $120 million renovation plan for terminal C that included installing 6,000 iPads and 55 new restaurants headed by celebrity chefs, with the first new restaurants opening in summer of 2015 and the whole project completed in 2016.[48]

Terminal One

In 2016, the Port Authority approved and announced a redevelopment plan to build a new Terminal A to replace the existing, which opened in 1973. Built on a site once occupied by United Parcel Service and the United States Postal Service,[35] the new terminal, named Terminal One, is expected to cost around $2.7 billion, and will include a new six-level, 3,000-car parking garage and rental center,[35] 33 gates, and a walkway to connect the AirTrain station, parking garage, and terminal building.[49][50][51][35] The project is expected to open in two phases, with the first in late-2021 and the second in late-2022.[35]

Designed by Grimshaw Architects, the redevelopment is expected to offer more traffic lanes at pick-up and drop-off points, closer check-in counters and security areas to the entrance, and more gate flexibility to allow planes to park at any gate in a "common-use" system.[35] Terminal One will have four levels: the departures level, the mezzanine level for offices, the arrivals level, and the ground floor, where baggage claim will be located.[35] The terminal will be operated as EWR Terminal One LLC by Munich Airport International, a subsidiary of Munich Airport, which will manage the terminal's operations, maintenance, and concessions in the 1 million square feet of retail space.[52] The redevelopment also comes with plans to replace the existing AirTrain monorail system, scheduled to open in 2024.[35]

Impact of COVID-19

As a result of the COVID-19 Pandemic, aircraft operations in Terminal A have drastically changed. Alaska Airlines trimmed its Newark schedule to just three daily flights and has leased their gates (A30 and A31) to JetBlue to accommodate their increased operations. In addition, United Airlines has vacated concourse A2 in favor of Terminal C for their operations. United has not yet announced when, or if, they will return to Terminal A. JetBlue currently utilizes Gates 15, 16, 16A, 17, 18, 21, 22, 30, and 31 in Terminal A and is now the dominant carrier of the Terminal.

Most international flights from the airport are still suspended with the exception of United's flights to major European, Latin American, and Caribbean destinations.

Ground transportation

Train

A monorail system, AirTrain Newark, connects the terminals with Newark Liberty International Airport Station. The station is served by New Jersey Transit's Northeast Corridor Line and North Jersey Coast Line, with connections to regional rail hubs such as Newark Penn Station, Secaucus Junction and New York Penn Station where transfers are available to any rail line in northern New Jersey or Long Island, New York. Amtrak's Northeast Regional and Keystone Service trains also stop at the Newark Liberty International Airport station. A fee for the AirTrain is included with rail ticket purchases, with the exception of children 11 and younger and customers using monthly passes with the airport as the origin or destination. Passengers can also ride the AirTrain for free between the terminals and the parking lots, parking garages, and rental car facilities.

In September 2012, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey announced that work would commence on a study to explore extending the PATH system to the station.[53] The new station would be located at ground level to the west of the existing NJ Transit station.[54] In 2014, the Board of Commissioners approved a formal proposal to extend the PATH to Newark Airport.[55] On January 11, 2017, the PANYNJ released its 10-year capital plan that included $1.7 billion for the extension. Under the plan, construction is projected to start in 2020, with service in 2026.[56][57]

In January 2019, New Jersey Governor Phil Murphy announced a plan for a $2 billion replacement project for AirTrain Newark. Murphy has stated that replacement is necessary because the system is reaching the end of its projected 25-year life and is subject to persistent delays and breakdowns. The Port Authority would be responsible for funding the project.[58] In October 2019, the Port Authority board approved the replacement project with an estimated cost of $2.05 billion. Construction is expected to start in 2021 and be completed in 2024.[59]

Bus

NJT buses operate northbound local service to Irvington, Downtown Newark and Newark Penn Station, where connections are available to the PATH and NJ Transit rail lines. The go bus 28 is a bus rapid transit line to Downtown Newark, Newark Broad Street Station and Bloomfield Station. Southbound service travels to Elizabeth, Lakewood, Toms River and intermediate points.

Olympia Trails operates express buses to the Port Authority Bus Terminal, Bryant Park and Grand Central Terminal in Manhattan,[60] and Super-Shuttle, Go Airport Shuttle and Go-link operate shared taxi services.[61]

Road

Private limousine, car service, and taxis also provide service to/from the airport. Taxis serving the airport charge a flat rate based on destination. For trips to/from New York, fares are set by the New York City Taxi and Limousine Commission.

The airport is served directly by U.S. Route 1/9, which provides connections to Route 81 and Interstate 78, both of which have interchanges with the New Jersey Turnpike (Interstate 95) at exits 13A and 14, respectively. Northbound, Route 1/9 becomes the Pulaski Skyway, which connects to Route 139. Route 139 continues east to the Holland Tunnel, which links Jersey City with Lower Manhattan.

The airport operates short and long term parking lots with shuttle buses and monorail access to the terminals. The shuttle bus fleet is slowly being upgraded to electric buses, with half the buses to be upgraded by the summer of 2019.[62]

A free cellphone lot waiting area is available for drivers picking up passengers at the airport.[63]

Airlines and destinations

Passenger

Cargo

Statistics

Top destinations

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Orlando, Florida | 595,000 | Frontier, JetBlue, Spirit, United |

| 2 | Fort Lauderdale, Florida | 455,000 | JetBlue, Spirit, United |

| 3 | Atlanta, Georgia | 422,000 | Delta, Frontier, Spirit, United |

| 4 | San Francisco, California | 411,000 | Alaska, JetBlue, United |

| 5 | Los Angeles, California | 406,000 | Alaska, JetBlue, United |

| 6 | Chicago–O'Hare, Illinois | 355,000 | American, Frontier, United |

| 7 | Charlotte, North Carolina | 343,000 | American, Spirit, United |

| 8 | Miami, Florida | 315,000 | American, Frontier, United |

| 9 | Houston–Intercontinental, Texas | 311,000 | Spirit, United |

| 10 | Denver, Colorado | 243,000 | Frontier, United |

| Rank | Airport | Passengers | Carriers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1,247,477 | United | |

| 2 | 1,045,933 | British Airways, United, Virgin Atlantic | |

| 3 | 619,855 | El Al, United | |

| 4 | 432,814 | Air Canada, United | |

| 5 | 408,596 | Porter Airlines | |

| 6 | 402,714 | United, Lufthansa | |

| 7 | 381,558 | JetBlue, United, VivaAerobus | |

| 8 | 374,317 | Air India, United | |

| 9 | 364,960 | Aer Lingus, United | |

| 10 | 325,001 | Cathay Pacific, United |

Airline market share

| Rank | Airline | Passengers | Share |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | United Airlines | 7,658,000 | 48.82% |

| 2 | JetBlue | 1,301,000 | 8.29% |

| 3 | American Airlines | 1,221,000 | 7.78% |

| 4 | Spirit Airlines | 1,051,000 | 6.70% |

| 5 | Delta Air Lines | 650,000 | 4.15% |

Annual traffic

| Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers | Year | Passengers |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 2010 | 33,107,041 | 2000 | 34,188,701 | |

| 2019 | 46,366,452 | 2009 | 33,424,110 | 1999 | 33,622,686 |

| 2018 | 46,065,175 | 2008 | 35,366,359 | 1998 | 32,575,874 |

| 2017 | 43,393,499 | 2007 | 36,367,240 | 1997 | 30,945,857 |

| 2016 | 40,351,331 | 2006 | 35,764,910 | 1996 | 29,117,464 |

| 2015 | 37,494,704 | 2005 | 33,078,473 | 1995 | 26,626,231 |

| 2014 | 35,600,108 | 2004 | 31,893,372 | 1994 | 28,019,984 |

| 2013 | 35,016,236 | 2003 | 29,428,899 | 1993 | 25,809,413 |

| 2012 | 34,014,027 | 2002 | 29,220,775 | 1992 | 24,284,248 |

| 2011 | 33,711,372 | 2001 | 31,100,491 | 1991 | 22,276,396 |

Airport information

Newark Airport, along with LaGuardia and Kennedy airports, uses a uniform style of signage throughout the airport properties. Yellow signs direct passengers to airline gates, ticketing and other flight services; green signs direct passengers to ground transportation services and black signs lead to restrooms, telephones and other passenger amenities. New York City traffic reporter Bernie Wagenblast provides the voice for the airport's radio station and curbside announcements, as well as the messages heard onboard AirTrain Newark and in its stations.

The airport has the IATA designation EWR, rather than a designation that begins with the letter 'N' because the designator of "NEW" is already assigned to Lakefront Airport in New Orleans, LA, and because the Department of the Navy uses three-letter identifiers beginning with N for its purposes.[116] The airport has no official area to view flight traffic, but the IKEA of Elizabeth (located on the East side of the New Jersey Turnpike) may be used as an unofficial vantage point for aircraft both departing and landing.

Accommodations

Within the Newark Liberty International Airport complex is a Marriott hotel, the only hotel located on airport property.[117] Shuttle vans operate between the hotel and terminals because the Marriott is not serviced by the monorail and there is no official walking route to the terminals, despite the Marriott's immediate proximity to the main parking lot between the terminals.

Accidents and incidents

- On March 17, 1929, a Colonial Western Airlines Ford Tri-Motor suffered a double engine failure during its initial climb after takeoff, failed to gain height, and crashed into a railroad freight car loaded with sand, killing 14 of the 15 people on board. At the time, it was the deadliest aviation accident in American history.[118]

- On January 14, 1933, Eastern Air Transport, a Curtiss Condor, crashed at Newark; two crewmembers were killed.[119]

- On May 4, 1947, Union Southern Airlines, a Douglas DC-3 with 12 passengers and crew, crashed on landing at Newark after overrunning the runway and into a ditch where it burned. Two crewmembers were killed.[120]

- On December 16, 1951, a Miami Airlines C-46 Commando (converted for passenger use) lost a cylinder on takeoff from Runway 28 and crashed in Elizabeth, killing 56.[14]

- On January 22, 1952, American Airlines Flight 6780, a Convair 240, crashed in Elizabeth on approach to Runway 6, killing 30.[15]

- On February 11, 1952, National Airlines Flight 101, a Douglas DC-6, crashed in Elizabeth after takeoff from Runway 24, killing 33.[17][121]

- On April 18, 1979, a New York Airways commuter helicopter on a routine flight to LaGuardia Airport and John F. Kennedy International Airport plunged 150 feet (46 m) into the area between Runways 4L/22R and 4R/22L, killing three passengers and injuring 15. It was later determined the crash was due to a failure in the helicopter's tail rotor.[122]

- On July 22, 1981, a railroad tank car carrying ethylene oxide caught fire at the Port Newark freight yard causing the evacuation of a one-mile radius, which included the evacuation of the North Terminal building of Newark International Airport.[123]

- On March 30, 1983, a Learjet 23 operated by Hughes Charter Air, a night check courier flight, crashed on landing at EWR during an unstabilized approach. Both crewmembers were killed. Marijuana was later found in their systems, impairing judgement.[124]

- On July 31, 1997, FedEx Flight 14, a McDonnell Douglas MD-11, crashed while landing after a flight from Anchorage International Airport. The Number 3 engine contacted the runway during a rough landing, which caused the aircraft to flip upside down. The aircraft was destroyed by fire. The two crewmembers and three passengers escaped uninjured.[125][126]

- On September 11, 2001, United Airlines Flight 93 took off from Newark. It was hijacked by four al-Qaeda terrorists and diverted towards Washington DC, with the intent of crashing the plane into either The Capitol or the White House. After learning of the previous attacks on the World Trade Center and The Pentagon, the passengers attempted to retake control of the plane. The passengers then forced the hijackers to crash the plane into a field in Pennsylvania.

- On January 10, 2010, United Airlines Flight 634, an Airbus A319, made an emergency landing after the aircraft's right main landing gear failed to deploy. No passengers or crew members were injured during the landing.[127] The aircraft sustained substantial damage in the accident.[128][129]

- On May 1, 2013, Scandinavian Airlines Flight 908, an A330-300 that was cleared for takeoff, collided with an ExpressJet Embraer ERJ-145 aircraft on the taxiway. The ERJ-145 lost its tail in the accident.[130]

- On May 18, 2013, a malfunctioning landing gear forced US Airways Flight 4560, a de Havilland Canada Dash 8-100, to make a belly landing. None of the passengers or crew were injured.[131]

- On March 2, 2019, Southwest Airlines Flight 6, a Boeing 737-700 registration N918WN, struck the tail of Southwest Flight 3133, a Boeing 737-700 parked at Gate A15 bound for Nashville, while taxiing to the runway. The incident is under review and both Southwest planes (N493WN and N918WN) were taken out of service for review. There were no injuries reported.[132]

- On June 15, 2019, United Airlines Flight 627, a Boeing 757-200 registration N26123, suffered fuselage damage on the nose landing gear from a hard landing. The aircraft reportedly skidded to the left side of runway 22L and the left main landing gear veered into the grass. Although no notable injuries were reported, the airport went into a complete ground stop, and flights were diverted to other airports. The Federal Aviation Administration is reviewing the incident.[133]

Notes

References

- "General Information". Panynj.gov. Retrieved 2019-03-07.

- "EWR (KEWR): NEWARK LIBERTY INTL, NEWARK , NJ - UNITED STATES". Aeronautical Information Services. Federal Aviation Administration. 27 February 2020. Retrieved 2 March 2020.

- "Census 2010: New Jersey - USATODAY.com". Usatoday30.usatoday.com. 2011-02-03. Archived from the original on 2017-07-29. Retrieved 2018-03-16.

- "Property owned and leased by the Port Authority" (PDF). January 16, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2015.

- Belson, Ken (10 July 2008). "Newark Liberty International Airport (NJ)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 15 May 2014. Retrieved 2011-04-12.

- "Airlines – Airport Guide". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on June 8, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Airlines Airport Guide" (Press release). PANYNJ. Archived from the original on July 11, 2017. Retrieved July 2, 2017.

- Aviation Department (September 15, 2014). July 2014 Traffic Study (PDF) (Report). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- "History of Newark Liberty International Airport". Newark Liberty International Airport. Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on June 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Comenas, Gary. "Abstract Expressionism: Arshile Gorky's Newark Airport Murals". Warholstars.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2012. Retrieved September 30, 2011.

- "Press Releases". Panynj.gov. Archived from the original on 2018-09-03. Retrieved 2018-09-02.

- "City Airport Opens Officially Tonight". The New York Times. December 1, 1939. p. 25. Archived from the original on July 26, 2018. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- The Official Aviation Guide (Timetables – Fares – Routes; General Information of the Airways; Air Mail – Passengers – Air Express). The Official Aviation Guide Company, Inc. Chicago, ILL. (Issued monthly). May, 1939 and August, 1940

- "Driscoll Demands Stricter Air Curbs; Says Crash That Killed 56 Shows the Need for Controls". The New York Times. December 19, 1951. p. 37. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved 2012-08-15.

- "Pilot Was on Instrument-Guided Approach; Ground Control 'Talks' Flier Off Course". The New York Times. January 23, 1952. p. 20. Archived from the original on April 4, 2017. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Accident Investigation Report, National Airlines, Inc., Elizabeth, New Jersey, February 11, 1952 (Report). Civil Aeronautics Board. May 16, 1952. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- Official Airline Guide, Washington DC: American Aviation Publications, 1957

- "EWR72". Departedflights.com. Archived from the original on 2018-01-19. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

- Avery, Brett (February 5, 2008). "30 and Counting: People Express". New Jersey Monthly. Archived from the original on August 31, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Wilson, Michael (August 22, 2002). "Governors Seek a Name Change for Newark Airport". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- Smothers, Ronald (August 30, 2002). "Port Authority Extends Lease of a Renamed Newark Airport". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2014. Retrieved March 13, 2010.

- "Singapore Airlines Ends Airbus A340-500 Service from late-Oct 2013". Routesonline.com. Archived from the original on 23 October 2018. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- Rosen, Eric. "World's New Longest Flight From Singapore to Newark Launches Today". Forbes.com. Archived from the original on 4 February 2019. Retrieved 23 January 2019.

- "Covid-19: Singapore Airlines and SilkAir Adjust Services in Response to Covid-19" (Press release). Singapore Airlines. 23 March 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-03-29. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "PAL to Fly to NY, Major US Cities". The Inquirer. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- "The longest non-stop flight in the world is returning to Newark". Nj.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-11. Retrieved 2015-12-07.

- "World's Longest Non-Stop Flight Returns To N.J. Airport". Patch.com. Archived from the original on 2015-12-10. Retrieved 2015-12-08.

- "Singapore Airlines will relaunch the world's longest flight, which will cover more than 10,000 miles and last 19 hours". Yahoo Finance. Archived from the original on May 31, 2018. Retrieved June 1, 2018.

- "Delay Reduction Plan (DRP)". New York Area Program Integration Office (NYAPIO). Federal Aviation Administration. Archived from the original on August 9, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Strunsky, Steve (March 6, 2014). "United Airlines throws open its new hangar doors at Newark airport". The Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 27, 2014. Retrieved May 26, 2014.

- "United Airlines Strengthens New York/New Jersey Hub with Move of p.s. Transcontinental Service to Newark" (Press release). United Airlines. June 16, 2015. Archived from the original on August 10, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- Newman, Richard; Alvarado, Monsy (7 July 2016). "Newark among 10 cities chosen for daily flights to Havana". NorthJersey.com. Archived from the original on 18 September 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- Todd, Susan (May 20, 2012). "United's dominance at Newark Liberty International Airport brings conveniences and higher fares". The Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey. Archived from the original on June 24, 2012. Retrieved October 26, 2012.

- Lynn, Kathleen (December 17, 2019). "Preparing for Takeoff: A Sneak Peek at Newark Airport's New Terminal". New Jersey Monthly. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- "United Airlines adding iPads at Newark airport gates, revolutionizes food ordering". Digital Trends. 2014-11-08. Archived from the original on 2018-05-14. Retrieved 2018-05-13.

- FAA Airport Form 5010 for EWR PDF, effective March 1, 2018.

- "Airport Guide – Newark Liberty International Airport". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on March 29, 2016. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- "A full information system for New York Airports". Mijksenaar. Archived from the original on October 16, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "Everything You Need to Know About Traveling Through Newark Airport". Travel + Leisure. Archived from the original on 4 August 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "Newark Airport Terminal A". www.airport-ewr.com. Archived from the original on 17 May 2019. Retrieved 12 September 2019.

- "Building a Better Airport". Newarkairport.com. Archived from the original on December 1, 2007. Retrieved 2013-06-28.

- Richards, Jodi (June 2014). "Top-To-Bottom Renovations Breathe New Life Into Newark Liberty". Airportimprovments.com. Retrieved 4 December 2020.

- Cardwell, Diane (February 17, 2014). "At Newark Airport, the Lights Are On, and They're Watching You". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 18 February 2014. Retrieved 18 February 2014.

- Read, Philip (March 25, 2010). "Architectural Firm That Shaped Newark, N.Y.C. Skylines Closes After 104 Years". The Star-Ledger. Newark, New Jersey. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved June 13, 2012.

- "Newark Liberty International Airport – old Continental Airlines Terminal C3 Expansion". SOM.com. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill. Archived from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "Continental Airlines Global Gateway Project". Binsky.com. Binsky & Snyder. Archived from the original on 4 May 2012. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- Green, Dennis (November 19, 2014). "Newark Airport Is Undergoing A Massive Renovation – Here's What It Will Look Like Inside". Business Insider. Archived from the original on May 24, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- "Port Authority has $6B plan for new airport terminals". NJ.com. Archived from the original on 2017-03-10. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- "The Port Authority of NY & NJ : Newark Liberty International Airport" (PDF). Panynj.gov. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-16. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- "Redevelopment – Newark Liberty Airport – The Port Authority of NY & NJ". Panynj.gov. Archived from the original on 2017-04-25. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- "Leading global airport operator to manage new 2.7 billion dollars Terminal One at Newark Libert". Munich Airport. July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 5, 2020.

- "PORT AUTHORITY TO UNDERTAKE STUDY ON EXTENDING PATH RAIL SERVICE TO NEWARK LIBERTY INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT" (Press release). PANYNJ. September 20, 2012. Archived from the original on October 11, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2012.

- "PATH Extension Project PUBLIC SCOPING MEETINGS National Environmental Policy Act" (PDF). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. November 28, 2017. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 29, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- "PORT AUTHORITY BOARD APPROVES HISTORIC $27.6 BILLION 10-YEAR CAPITAL PLAN THAT FOCUSES THE AGENCY ON ITS CORE TRANSPORTATION MISSION". Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. February 19, 2014. Archived from the original on February 22, 2017. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- PANYNJ Proposed Capital Plan 2017-2026 Archived 2017-02-02 at the Wayback Machine, page 38 January 11, 2017

- "What's the Plan for PATH Service to Newark Liberty Airport? - NJ Spotlight". Njspotlight.com. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- Reitmeyer, John. "Murphy Wants to Replace Newark Airport Monorail, No More 'Bubblegum' Fixes". Nj Spotlight. Retrieved February 11, 2019.

- Higgs, Larry (October 24, 2019). "Big money fixes coming to Newark airport's monorail, PATH stations". NJ.com.

- "Newark Airport Express". Coach USA. Archived from the original on May 25, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- "Connecticut Airport Shuttle Service". Go Airport Shuttle. Archived from the original on August 8, 2013. Retrieved August 30, 2015.

- Hutter, David (2019-04-23). "Airport shuttle bus fleets to be 50 percent electric by summer, PANYNJ says". NJBIZ. Archived from the original on 2019-04-28. Retrieved 2019-04-28.

- "Cellphone lot at Newark International Liberty Airport". Port Authority of NY & NJ. Archived from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 22 December 2016.

- "TImetables". Aer Lingus. Archived from the original on 2017-02-19. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Flight Schedules". Air Canada. Archived from the original on 2018-03-23. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Flight Timetable". Airchina.com. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Time Table - Air India". Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Flight Timetable". Alaskaair.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- https://airlinegeeks.com/2020/11/17/allegiant-announces-john-wayne-service-and-grand-rapids-additions/

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Allegiantair.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2011. Retrieved April 10, 2018.

- "Flight schedules and notifications". Aa.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Austrian Timetable". Austrian Airlines. Archived from the original on 2019-03-31. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Check itineraries". Avianca.com. Archived from the original on 5 March 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Timetables". British Airways. Archived from the original on 2017-03-30. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "FLIGHT SCHEDULES". Delta.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2015. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Flight Schedule". El Al. Archived from the original on 2018-11-18. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Flight status". Archived from the original on 9 April 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Flight Schedules". Emirates. Archived from the original on 2017-06-30. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Schedule - Fly Ethiopian". Archived from the original on 31 March 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- Liu, Jim. "French Bee delays New York service to late Dec 2020". Routesonline. Retrieved September 14, 2020.

- "Timetable - French Bee". Archived from the original on April 14, 2018. Retrieved April 13, 2018.

- https://www.flyfrontier.com/travel/my-trips/route-map/?mobile=true

- "Flight Schedule". Icelandair. Archived from the original on 2017-11-16. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "JetBlue adds 4 new cities, including Miami, in 24-route expansion". Retrieved December 17, 2020.

- "JetBlue Airlines Timetable". Archived from the original on 13 July 2013. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/288788/jet2com-4q20-newark-operation-changes-as-of-14jan20/?highlight=Jet2

- "La Compagnie - Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on 4 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- "Timetables". LOT Polish Airlines. Archived from the original on 2017-05-06. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Timetable - Lufthansa Canada". Lufthansa. Archived from the original on 2017-11-09. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Interactive Route Map". Archived from the original on 15 November 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Timetable - SAS". Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Flight schedules". Archived from the original on 12 May 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Spirit Airlines expands Austin / Nashville network in 1Q20". Routes Online. October 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2019.

- "Where We Fly". Spirit Airlines. Archived from the original on 23 December 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Route Map & Flight Schedule". Archived from the original on 15 August 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on 17 March 2018. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- "All Destinations". TAP Portugal. Archived from the original on 2017-05-12. Retrieved 2018-04-11.

- "Turkish Airlines continues to delay Newark / Vancouver service to Jan 2021". Routes Online. October 2020. Retrieved October 6, 2020.

- https://airwaysmag.com/airlines/united-barbados-winter-2021/?fbclid=IwAR2OA3heprIoumnSqhs5jRgoqO8qcwuwkQlF7a7tMLBn_AnUSMg_e4DpMa4

- Liu, Jim. "United NW20 Long-Haul operations as of 02OCT20". Airlineroute. Retrieved 3 October 2020.

- Liu, Jim. "United extends International / Guam / Micronesia Island Hopper interim schedule to Sep 2020". Airlineroute. Retrieved 5 July 2020.

- "United Airlines Plans to Increase Service on More than 40 Caribbean and Mexican Beach Routes in November". United. Retrieved October 2, 2020.

- https://www.routesonline.com/news/38/airlineroute/293996/united-adds-new-hawaii-routes-from-june-2021/

- "United S20 International service changes as of 22AUG19". Routes Online. August 2019. Archived from the original on September 2, 2019. Retrieved September 12, 2019.

- "Timetable". Archived from the original on 28 January 2017. Retrieved 10 April 2018.

- https://www.msn.com/en-us/travel/news/united-airlines-resumes-existing-adds-new-service-to-key-west/ar-BB196Ugg?li=BBnbklE

- "Viva Aerobus re activates 7 routes for the winter season" (in Spanish). EnElAire. December 2019. Retrieved December 3, 2019.

- "Newark, NJ: Newark Liberty International (EWR)". Bureau of Transportation Statistics. U.S. Department of Transportation. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- "BTS Air Carriers : T-100 International Market (All Carriers)". Archived from the original on June 15, 2018. Retrieved June 17, 2018.

- "Airport Traffic Report" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 May 2020. Retrieved 6 April 2019.

- Aviation Department. Monthly Summaries of Airport Activities (PDF) (Report). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- Aviation Department. December 2014 Traffic Report (PDF) (Report). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- "Facts & Information". Newark Liberty International Airport. Port Authority of New York & New Jersey. Archived from the original on May 26, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- Airport Traffic Report (PDF) (Report). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. 1997. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- Airport Traffic Report (PDF) (Report). Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. 2002. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- "Air Traffic Organization Policy" (PDF). Regulations & Policies. Federal Aviation Administration. June 25, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 6, 2015. Retrieved August 28, 2015.

- "Newark Liberty International Airport Marriott". Marriott.com. Archived from the original on July 23, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- "ASN Aircraft accident Ford 4-AT-B Tri-Motor NC7683 Newark Airport, NJ (EWR)". Aviation-safety.net. Archived from the original on 2016-12-21. Retrieved 2017-04-03.

- Accident description for NC185H at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on May 1, 2019.

- Accident description for NC53196 at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on May 1, 2019.

- "Elizabeth, NJ Plane Crash Kills 28, Jan 1952". The Post-Standard. Syracruse, New York. January 23, 1952. Archived from the original on September 1, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- Aircraft Accident Report, New York Airways, Inc., Sikorrsky S61-L, N618PA, Newark, New Jersey, April 18, 1979 (PDF) (Report). National transportation Safety Board. September 27, 1979. Archived from the original on October 4, 2012. Retrieved August 31, 2015.CS1 maint: unfit URL (link)

- People Exp. Airlines, Inc. v. Consolidated Rail, 100 N.J. 246 (N.J. 1985)

- Accident description for N51CA at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on May 1, 2019.

- "ASN Aircraft accident McDonnell Douglas MD-11F N611FE Newark International Airport, NJ (EWR)". Aviation-safety.net. Archived from the original on July 31, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- Aircraft Accident Report, Crash During Landing, Federal Express, Inc., McDonnell Douglas MD-11, N611FE, Newark International Airport, Newark, New Jersey, July 31, 1997 (Report). National transportation Safety Board. July 25, 2000. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- Sulzberger, A.G.; Schweber, Nate (January 10, 2010). "Plane Makes Emergency Landing at Newark Airport". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 13, 2010. Retrieved January 10, 2010.

- "Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Archived from the original on January 18, 2010. Retrieved January 11, 2010.

- Hutchinson, Bill (January 10, 2010). "Emergency landing by United Airlines Flight 634 shuts down Newark Liberty International Airport". Daily News (New York). Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "United Express, SAS planes clip each other at Newark". USA Today. Newark, New Jersey. May 2, 2013. Archived from the original on October 17, 2015. Retrieved August 31, 2015.

- "Plane Makes Belly Landing at Newark Airport". The New York Times. May 18, 2013. Archived from the original on June 12, 2013. Retrieved June 28, 2013.

- "2 Southwest airplanes clip wings at Newark airport". Archived from the original on 2019-03-03. Retrieved 2019-03-03.

- "Tires blow on United jet during Newark airport landing, no injuries" (3 ed.). New York City: Thomson Reuters. Reuters. 15 June 2019. Archived from the original on 27 June 2019. Retrieved 27 June 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Newark Liberty International Airport. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Newark Liberty International Airport. |

- Newark Liberty International Airport (official site)

- "World's Busiest Airport" Popular Mechanics, May 1937

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NJ-133, "Newark International Airport"

- How To Get To Newark Airport

- Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms, a National Park Service Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary

- FAA Airport Diagram (PDF), effective January 28, 2021

- Resources for this airport:

- AirNav airport information for KEWR

- ASN accident history for EWR

- FlightAware airport information and live flight tracker

- NOAA/NWS weather observations: current, past three days

- SkyVector aeronautical chart for KEWR

- FAA current EWR delay information

- OpenNav airspace and charts for KEWR

.jpg.webp)