People's Republic of Mozambique

The People's Republic of Mozambique (Portuguese: República Popular de Moçambique) was a socialist state that existed in present day Mozambique from 1975 to 1990.

People's Republic of Mozambique República Popular de Moçambique | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1975–1990 | |||||||||

Motto: Unidade, Trabalho, Vigilância (English: "Unity, Work, Vigilance") | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Capital | Lourenço Marques (1975-1976) Maputo (1976-1990) | ||||||||

| Largest city | Maputo | ||||||||

| Official languages | Portuguese | ||||||||

| Religion | State atheism (de facto) Roman Catholicism, Islam | ||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Mozambican | ||||||||

| Government | Unitary Marxist–Leninist one-party socialist republic | ||||||||

| President | |||||||||

• 1975–1986 | Samora Machel | ||||||||

• 1986 | Political Bureau | ||||||||

• 1986–1990 | Joaquim Chissano | ||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||

• 1986–1990 | Mário da Graça | ||||||||

| Legislature | People's Assembly | ||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||

| 8 September 1974 | |||||||||

• Independence from Portugal | 25 June 1975 | ||||||||

• Mozambican Civil War begins | 30 May 1976 | ||||||||

| 30 November 1990 | |||||||||

| Area | |||||||||

• Total | 801,590 km2 (309,500 sq mi) | ||||||||

• Water (%) | 2.2 | ||||||||

| Currency | Escudo (MZE) (1975–1980) Metical (MZM) (1980–1990) | ||||||||

| Driving side | left | ||||||||

| Calling code | +258 | ||||||||

| ISO 3166 code | MZ | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The People's Republic of Mozambique was established when the country gained independence from Portugal in June 1975 and the Mozambican Liberation Front ("FRELIMO") established a one-party socialist state led by Samora Machel. After a few years of peaceful development it quickly became engaged in a deadly war of destabilization with the Mozambique National Resistance ("MNR"), a pseudo-guerrilla anti-communist movement created and initially financed by Rhodesia (present-day Zimbabwe), but later supplanted by the then apartheid regime of South Africa, who continued to support and finance the group until the signing of the Rome General Peace Accords in 1992.[2]

The People's Republic of Mozambique enjoyed close relations with the People's Republic of Angola,[3] the Soviet Union,[4] and the German Democratic Republic, which were socialist states at the time.[5] The People's Republic of Mozambique was also an observer of the COMECON ("Council for Mutual Economic Assistance"), which was an economic organization of socialist states.[6] However in its final years the People's Republic sought rapprochement with the United States of America, the International Monetary Fund and the German Federal Republic after the death of Samora Machel and the beginning of economic reforms under Joaquim Chissano.

Geographically the People's Republic of Mozambique is the exact same as the present day Republic of Mozambique, located on the southeast coast of Africa. Bordered by Eswatini to the south, South Africa to the southwest, Zimbabwe to the west, Zambia and Malawi to the northwest, Tanzania to the north and the Indian Ocean to the east.

History

Liberation struggle

Lusaka Accord and independence

Following the collapse of the corporatist Estado Novo regime during the Carnation Revolution in Portugal in 1974 the new Portuguese government began a slow process of withdrawal from Africa. In initial negotiations with the new Portuguese government FRELIMO and Samora Machel rejected attempts for a ceasefire and referendum insisting these would impose in Mozambique a neo-colonial solution. Samora Machel laid out three main prerequisites for peace: recognition of FRELIMO as the Mozambican people's legitimate representative; recognition of the Mozambican people's right to complete independence; and the transfer of power to FRELIMO. The talks were initially broken off before quietly being resumed later in the year.[7][8]

By mid-1974 Portugal's imperial power in Mozambique was quickly crumbling. White settlers were quickly abandoning the country and troops were either deserting, refusing to fight or pleading with FRELIMO for ceasefires. As this was occurring FRELIMO forces continued to penetrate further south into the country, putting pressure on the Portuguese government to find a solution to the Mozambique issue. On 7 September 1974, The Lusaka Accord on the independence of Mozambique was signed by Samora Machel for FRELIMO and Mozambique, and by Ernesto Melo Antunes and several colleagues for Portugal after months of public and private negotiation. A transitional government led by Joaquim Chissano was then installed on 20 September 1974 composed of six FRELIMO and four Portuguese members. It served as a caretaker government until independence came on 25 June 1975.[9]

Within hours of the signing of the Lusaka Accord the first of many groups of rebels appeared. A group of former Portuguese commandos calling themselves "The Dragons of Death" seized the radio station in Lourenço Marques and attempted to stage a coup.[10] They released about 200 detained PIDE agents in Lourenço Marques while other supporters of the Dragons began touring black townships in open vehicles, shooting at black Mozambicans randomly. The coup attempt lasted one weekend until the FRELIMO controlled Portuguese managed to force the rebels to leave the country.

During this transitional period FRELIMO had to find ways of creating a structure for people's power in the country. FRELIMO chose to do this through workplace democracy and with its own invention of grupos dinamizadores or "dynamizing groups." These groups were formed to agitate, organise and educate Mozambicans about FRELIMO, socialism and the problems facing the country.[11] The dynamic groups quickly grew in size and most workplaces and towns had their own local grupo dinamizador by Independence in 1975.

The Central Committee of FRELIMO adopted the constitution of the People's Republic of Mozambique on June 20, which established that power belongs to the workers and peasants "united and led by FRELIMO and by the organs of people's power." The country's independence was officially proclaimed five days later. Under the new system, FRELIMO was officially the "leading force of the state and society," the President was automatically president of the Republic, President of the People's Assembly, and, until in 1986, head of government. Mozambique had a planned economy. The state recognized private property, but stated that it "cannot be used against the interests defined the constitution." The territory was divided into provinces headed by governors appointed by the president and governed "in accordance with FRELIMO and the government." The governors had authority over the district administrators and local administrators.[12]

The first months of the presidency of Samora Machel were marked by a series of radical measures: land, education and health were nationalized; three radio stations were abolished and replaced by a national state radio; and the press fell under the control of the government and the party.[13] The independent state continued FRELIMO's policy of alliance with communist countries, which it considered its "natural allies."[12][14]

War of Destabilisation

Climate

The People's Republic of Mozambique had a tropical climate with two seasons, a wet season from October to March and a dry season from April to September. Climatic conditions varied depending on altitude. Rainfall was typically heavy along the coast and decreased in the north and south. Annual precipitation varied from 500 to 900 mm (19.7 to 35.4 in) depending on the region, with an average of 590 mm (23.2 in). Cyclones were common during the wet season. Average temperature ranges in Maputo were from 13 to 24 °C (55.4 to 75.2 °F) in July and from 22 to 31 °C (71.6 to 87.8 °F) in February.

The People's Republic of Mozambique experienced numerous extreme weather events, most notable were Tropical Storm Domoina in 1984 and an extensive drought and famine from 1985 to 1987.

Politics

Armed Forces of Mozambique – FPLM

Upon independence in 1975 the guerilla forces of FRELIMO, the People's Forces for the Liberation of Mozambique (Forças Populares de Libertação de Moçambique - FPLM) was reorganised into the Armed Forces of Mozambique (Forças Armadas de Moçambique - FAM), the official designation being "Forças Armadas de Moçambique - FPLM."

The FAM was initially organised along similar lines to its predecessor, with no formal ranks[15] besides from a system of "comandantes" who were elected to the position by fellow soldiers. FRELIMO and the FAM/FPLM were virtually indistinguishable from each other following their close relationship through the liberation struggle. In December 1975 Mozambique was rocked by an abortive rebellion in Lourenço Marques (Maputo) when 400 troops of the FAM occupied strategic positions in Machava before being forced back by loyal police, military and civilians. The rebellion was in response to a crackdown and purge on corruption within the military and party.[16]

Because of the FAM/FPLM's close connection with the Mozambican people, corruption was rarely an issue and abuses of power were often reported with harsh punishments, with 8 soldiers arrested and imprisoned in March 1977 after reports of serious abuses against the people.[17]

Education

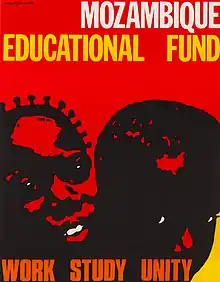

Public schools lacked basic supplies, and fundraising efforts began by groups like the Mozambique Educational Fund in the United States.[18][19]

Culture

Public holidays

| Date | English Name |

|---|---|

| 1 January | New Year's Day |

| 3 February | Heroes' Day |

| 7 April | Mozambican Women's Day |

| 1 May | Workers' Day |

| 25 June | Independence Day |

| 7 September | Victory Day |

| 25 September | Revolution Day |

| 25 December | Family Day |

Gallery

.svg.png.webp) Flag (1975–1983)

Flag (1975–1983).svg.png.webp) Flag (1983)

Flag (1983) Flag (1983–1990)

Flag (1983–1990)

.svg.png.webp) Emblem (1975–1982)

Emblem (1975–1982).svg.png.webp) Emblem (1982–1990)

Emblem (1982–1990)

Bibliography

- Priestland, David (2009). The Red Flag: a History of Communism. New York: Grove Press. ISBN 9780802145123.

- Christie, Iain (1988). Machel of Mozambique. Harare: Zimbabwe Publishing House. ISBN 9780949225597.

- Isaacman, Allen & Barbara (1983). Mozambique: From Colonialism to Revolution. Boulder: Westview Press, Inc. ISBN 9780566005480.

References

- "The Constitution of the Republic of Mozambique, 1990" (PDF). World Bank. 2 November 1990. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- "Mozambique". Encarta. Archived from the original on 28 October 2009.

- de la Fosse Wiles, Peter John (1982). The New Communist Third World. Croom Helm. ISBN 978-0709927099.

- "Soviet Union-Mozambique". May 1989.

- "Angola: Communist nations". February 1989.

- Burant, Stephen R. "Appendix B: The Council for Mutual Economic Assistance". East Germany : a country study (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 300. LCCN 87600490.

- Houser, George; Shore, Herb (1975). MOZAMBIQUE: Dream the Size of Freedom (PDF). The Africa Fund.

- Mario, Mouzinho; Nandja, Debora (2006). "Literacy in Mozambique: education for all challenges". UNESCO.

- "O Governo Transitório Moçambicana" Tempo Magazine, 1974.

- "Mozambique Radio Seized by Ex‐Portuguese Soldiers". The New York Times. 7 September 1974.

- CEEC, "Os Grupos Dinamizadores Em Moçambique" February 1975

- "Constituição Da República Popular De Moçambique" (PDF) (in Portuguese). June 1975.

- Madeley, R.; Jelley, D.; O'Keefe, P. (1983). "The Advent of Primary Health Care in Mozambique". Ambio. 12 (6, The Indian Ocean): 322–325. JSTOR 4312958.

- Müller, Tanja R. (2014). Legacies of Socialist Solidarity: East Germany in Mozambique. Lexington Books. ISBN 978-0739179420.

- Costa Kumalija, "Frelimo to abolish army ranks" Daily News (DSM), 5 June 1975

- Costa Kumalija, "Storm in a Teacup" Africa no 55, March 1976

- "Maputo reports on arrest of eight FPLM members" Summary of World Broadcasts VII Southern Africa, 25 March 1977

- "Letter/Mozambique Educational Fund". ASA News. Cambridge University Press. October 1977. pp. 10–11. ISSN 0278-2219.

- Isaacman, Allen (5 December 1977). "Letter" (PDF). African Activist Archive.