Soviet Empire

The Soviet Empire or the New Russian Empire are informal terms that have two meanings. In the narrow sense, it expresses a view in Western Sovietology that the Soviet Union as a state was a colonial empire. The onset of this interpretation is traditionally attributed to Richard Pipes's book The Formation of the Soviet Union (1954).[1] In the wider sense, it refers to the country's perceived imperialist foreign policy during the Cold War. The other term is sometimes used since Vladimir Putin took office in 2000.[2]

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Politics of the Soviet Union |

|---|

|

|

|---|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Russian Federation |

|

|

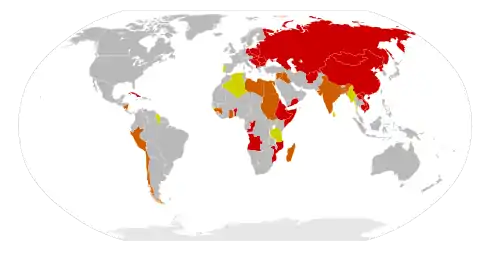

The nations said to be part of the Soviet Empire in the wider sense were officially independent countries with separate governments that set their own policies, but those policies had to remain within certain limits decided by the Soviet Union and enforced by threat of intervention by the Warsaw Pact (Hungary in 1956, Czechoslovakia in 1968 and Poland in 1980). Countries in this situation are often called satellite states. Similarly, the post-Soviet states and countries formerly allied with the Soviet Union continue to improve relations.

Characteristics

Although the Soviet Union was not ruled by an emperor and declared itself anti-imperialist and a people's democracy, critics[3][4] argue that it exhibited tendencies common to historic empires. Some scholars hold that the Soviet Union was a hybrid entity containing elements common to both multinational empires and nation states.[3] It has also been argued that the Soviet Union practiced colonialism as did other imperial powers.[4] Maoists argued that the Soviet Union had itself become an imperialist power while maintaining a socialist façade. The other dimension of "Soviet imperialism" is cultural imperialism. The policy of Soviet cultural imperialism implied the Sovietization of culture and education at the expense of local traditions.[5]

The history of relationship between Russia (the Soviet dominant republic) and these Eastern European countries helps to understand the reactions of the Eastern European countries to the remnants of Soviet culture, namely hatred and longing for eradication. Poland and the Baltic states epitomize the Soviet attempt at the uniformization of their cultures and political systems. According to Noren, Russia was seeking to constitute and reinforce a buffer zone between itself and Western Europe so as to protect itself from potential future attacks from hostile Western European countries.[6] It is important to remember that the 15 socialistic republics in the USSR lost between 26 and 27 million lives over the course the Second World War.[7] To this end, the Soviet Union needed to expand their influences so as to establish a hierarchy of dependence between the targeted states and itself. Such a purpose could be best achieved by means of the establishment of economic cronyism.

The penetration of the Soviet influence into the "socialist-leaning countries" was also of the political and ideological kind as rather than getting hold on their economic riches, the Soviet Union pumped enormous amounts of "international assistance" into them in order to secure influence,[8] eventually to the detriment of its own economy. The political influence they sought to pursue aimed at rallying the targeted countries to their cause in the case of another attack from Western countries and later as a support in the context of the Cold War.[9] After the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Russia declared itself successor and recognized $103 billion of Soviet foreign debt while claiming $140 billion of Soviet assets abroad.[8]

This does not mean that economic expansion did not play a significant role in the Soviet motivation to spread influence in these satellite territories. In fact, these new territories would ensure an increase in the global wealth which the Soviet Union would have a grasp on.[9] If we follow the theoretical communist ideology, this expansion would contribute to a higher portion for every Soviet citizen through the process of redistribution of wealth.

Soviet officials from the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic intertwined this economic opportunity with a potential for migration. In fact, they saw in these Eastern European countries the potential of a great workforce. They offered a welcome to them upon the only condition that they work hard and achieve social success. This ideology was shaped on the model of the meritocratic, 19th-century American foreign policy.[9]

Allies of the Soviet Union

Warsaw Pact

These countries were the closest allies of the Soviet Union and were members of the Comecon, a Soviet-led economic community founded in 1949, as well as the Warsaw Pact, sometimes called the Eastern Bloc in English and widely viewed as Soviet satellite states. These countries were occupied or had a period occupied by Soviet Army and their politics, military, foreign and domestic policies were dominated by the Soviet Union. The Soviet Empire is considered to have included the following states:[10][11]

.svg.png.webp) People's Socialist Republic of Albania (1946–1961)[lower-alpha 1]

People's Socialist Republic of Albania (1946–1961)[lower-alpha 1].svg.png.webp) People's Republic of Bulgaria (1946–1990)

People's Republic of Bulgaria (1946–1990) Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (1948–1990)

Czechoslovak Socialist Republic (1948–1990) German Democratic Republic (1949–1990)

German Democratic Republic (1949–1990) Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989)

Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) Polish People's Republic (1947–1989)

Polish People's Republic (1947–1989).svg.png.webp) Socialist Republic of Romania (1947–1968)[lower-alpha 2]

Socialist Republic of Romania (1947–1968)[lower-alpha 2]

In addition to the Soviet Union in the United Nations Security Council, the Soviet Union had two of its republics in the United Nations General Assembly:

Other Marxist–Leninist states allies with the Soviet Union

These countries were Marxist-Leninist states who were allied with the Soviet Union, but were not part of the Warsaw Pact.

.svg.png.webp) Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (1978–1991)

Democratic Republic of Afghanistan (1978–1991) People's Republic of Angola (1975–1991)[lower-alpha 3]

People's Republic of Angola (1975–1991)[lower-alpha 3].svg.png.webp) People's Republic of Benin (1975–1990)

People's Republic of Benin (1975–1990) People's Republic of China (1949–1961)[lower-alpha 4]

People's Republic of China (1949–1961)[lower-alpha 4] People's Republic of the Congo (1969–1991)

People's Republic of the Congo (1969–1991) Republic of Cuba (1959–1991)

Republic of Cuba (1959–1991).svg.png.webp) Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, then People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (1974–1991)

Provisional Military Government of Socialist Ethiopia, then People's Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (1974–1991) People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979–1989)

People's Republic of Kampuchea (1979–1989) People's Revolutionary Government of Grenada (1979–1983)

People's Revolutionary Government of Grenada (1979–1983) Democratic People's Republic of Korea (1948–1991, also allied with China)[12][lower-alpha 5]

Democratic People's Republic of Korea (1948–1991, also allied with China)[12][lower-alpha 5] Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–1991)

Lao People's Democratic Republic (1975–1991).svg.png.webp) Mongolian People's Republic (1924–1991)

Mongolian People's Republic (1924–1991).svg.png.webp) People's Republic of Mozambique (1975–1990)

People's Republic of Mozambique (1975–1990) Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977)[lower-alpha 6]

Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977)[lower-alpha 6].svg.png.webp) Tuvan People's Republic (1921–1944)[lower-alpha 7]

Tuvan People's Republic (1921–1944)[lower-alpha 7] Democratic Republic of Vietnam (1945–1976), then Socialist Republic of Vietnam (1976–1991)[lower-alpha 8]

Democratic Republic of Vietnam (1945–1976), then Socialist Republic of Vietnam (1976–1991)[lower-alpha 8].svg.png.webp) Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1948)[lower-alpha 9]

Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia (1945–1948)[lower-alpha 9] People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) (1967–1990)

People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (South Yemen) (1967–1990)

Non-Marxist–Leninist countries allied with the Soviet Union

Some countries in the Third World had pro-Soviet governments during the Cold War. In the political terminology of the Soviet Union, these were "countries moving along the socialist road of development" as opposed to the more advanced "countries of developed socialism" which were mostly located in Eastern Europe, but that also included Cuba and Vietnam. They received some aid, either military or economic, from the Soviet Union and were influenced by it to varying degrees. Sometimes, their support for the Soviet Union eventually stopped for various reasons and in some cases the pro-Soviet government lost power while in other cases the same government remained in power, but ultimately ended its alliance with the Soviet Union.[15]

Algeria (1962–1990)

Algeria (1962–1990) People's Republic of Bangladesh (1971–1975)

People's Republic of Bangladesh (1971–1975) Burkina Faso (1983–1987)

Burkina Faso (1983–1987).svg.png.webp) Burma (1962–1988)

Burma (1962–1988).svg.png.webp) Cape Verde (1975–1990)

Cape Verde (1975–1990) Chile (1970–1973)

Chile (1970–1973).svg.png.webp) Egypt (1954–1973)

Egypt (1954–1973).svg.png.webp) Ghana (1964–1966)

Ghana (1964–1966) Guinea (1960–1978)

Guinea (1960–1978) Guinea Bissau (1973–1991)

Guinea Bissau (1973–1991) Equatorial Guinea (1968–1979)

Equatorial Guinea (1968–1979) India (1971–1989)

India (1971–1989) Indonesia (1959–1965)

Indonesia (1959–1965)%253B_Flag_of_Syria_(1963%E2%80%931972).svg.png.webp) Iraq (1958–1963; 1968–1991)

Iraq (1958–1963; 1968–1991).svg.png.webp) Libya (1969–1991)

Libya (1969–1991) Democratic Republic of Madagascar (1972–1991)

Democratic Republic of Madagascar (1972–1991) Mali (1960–1968)

Mali (1960–1968) Nicaragua (1979–1990)

Nicaragua (1979–1990) Peru (1968–1975)

Peru (1968–1975) Sao Tome and Principe (1975–1991)

Sao Tome and Principe (1975–1991).svg.png.webp) Seychelles (1977–1991)

Seychelles (1977–1991) Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977)

Somali Democratic Republic (1969–1977) Sudan (1968–1972)

Sudan (1968–1972) Syria (1955–1991)

Syria (1955–1991)

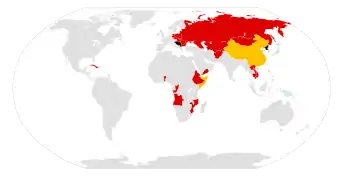

Marxist–Leninist states opposed to the Soviet Union

Some communist states were sovereign from the Soviet Union and criticized many policies of the Soviet Union. Relations were often tense, sometimes even to the point of armed conflict.

.svg.png.webp) Albania (1955–1991)

Albania (1955–1991) Cambodia (1975–1979)[lower-alpha 10]

Cambodia (1975–1979)[lower-alpha 10] China (1956–1991)

China (1956–1991).svg.png.webp) Romania (1968–1989)

Romania (1968–1989).svg.png.webp) Yugoslavia (1948–1991)

Yugoslavia (1948–1991)

Allies of Russia

CIS and CSTO

After the Cold War ended the following countries in the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) that have maintained close relations with the Russian Federation:

Armenia

Armenia Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan Belarus

Belarus Georgia[lower-alpha 11]

Georgia[lower-alpha 11] Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan Moldova

Moldova Tajikistan

Tajikistan Turkmenistan[lower-alpha 12]

Turkmenistan[lower-alpha 12] Ukraine[lower-alpha 13]

Ukraine[lower-alpha 13] Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

Within the former Soviet republics, there are partially recognized states fully or partially supported by Russia:

Russian-allied states

The following countries that have been aligned with Russia after the rise of Vladimir Putin in 2000.[16]

Neutral states

The position of Finland was complex. In World War II, Finland, after having signed the Moscow Peace Treaty in 1940, decided nevertheless to attack the Soviet Union as an ally of Nazi Germany in 1941, in what is known in Finland as the Continuation War. At the end of the war, Finland still remained in control of most of its territory, notwithstanding their status as losing powers. Finland also had a market economy, traded on the Western markets and joined the Western currency system. Nevertheless, although Finland was considered neutral, the Finno-Soviet Treaty of 1948 significantly limited the freedom of operation in Finnish foreign policy. It required Finland to defend the Soviet Union from attacks through its territory, which in practice prevented Finland from joining NATO and effectively gave the Soviet Union a veto in Finnish foreign policy. Thus, the Soviet Union could exercise "imperial" hegemonic power even towards a neutral state.[17] The Paasikivi–Kekkonen doctrine sought to maintain friendly relations with the Soviet Union and extensive bilateral trade developed. In the West, this led to fears of the spread of "Finlandization", where Western allies would no longer reliably support the United States and NATO.[18]

Post-Soviet era reactions to persisting Soviet and Russian influence

Ukraine

The process of decommunization and de-Sovietization started soon after dissolution of the Soviet Union in early 1990s by the President of Ukraine Leonid Kravchuk, a former high-rank party official.[19] After an early presidential election in 1994 that made a former "red director" Leonid Kuchma the President of Ukraine, the process came to near complete halt.

In April 2015, a formal decommunization process started in Ukraine after laws were approved which outlawed communist symbols, among other things.[20]

On 15 May 2015, President Petro Poroshenko signed a set of laws that started a six-month period for the removal of communist monuments (excluding World War II monuments) and renaming of public places named after communist-related themes.[21][22] At the time, this meant that 22 cities and 44 villages were set to get a new name.[23] Until 21 November 2015, municipal governments had the authority to implement this;[24] if they failed to do so, the provincial authorities had until 21 May 2016 to change the names.[24] If after that date the settlement had retained its old name, the Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine would wield authority to assign a new name to the settlement.[24] In 2016, 51,493 streets and 987 cities and villages were renamed, and 1,320 Lenin monuments and 1,069 monuments to other communist figures removed.[25]

Ukraine was also one of the most heavily influenced countries by the Soviet government and to this day by the Russian political power. The 41-year-old comedian Volodymyr Zelensky became the President-elect of Ukraine on 21 April 2019.[26] Zelensky unseated predecessor Petro Poroshenko, who became involved in the Ukrainian political life since 2004 and was appointed to different positions since then.[26] The Zelenskyi Presidency since election has been marred with controversies, due to his attempt to seek closer tie to Russia, and the approval of controversial autonomy law for Donetsk and Luhansk, believed to be helping Russia rather than Ukraine.[27] It is to be noted, however, that according to the Minsk Package of Implementation measures, the government of Ukraine should have in any case enshrined the autonomous status of the Donetsk and Luhansk areas in the Constitution by 2015.[28]

Poland

In 2018, Poland carries on with its project to continually demolish statues erected in favor of Soviet occupiers. Warsaw justifies such radical measures by its counter-reactionary approach to persisting domination of the Soviet culture in satellite states like itself. This has sparked fervent controversy with Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov and Director of the Information and Press Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation Maria Zakharova, who have lashed out at Warsaw officials for destroying the history that links the two countries together. On the other hand, Poland is seeking to eliminate all materialistic reminders of a persisting Soviet dominance as there have historically been many wars against the Russian Empire in the latter's efforts to invade Polish territory.[6]

Czech Republic

In April 2020, a statue of Soviet Marshal Ivan Konev was removed from Prague, which prompted criminal investigation by Russian authorities who considered it as an insult. Mayor of Prague's sixth municipal district Ondřej Kolář announced on Prima televize that he would be under police protection after a Russian man made attempts on his life. Prime Minister Andrej Babiš condemned that as foreign interference, while Kremlin Press Secretary Dmitry Peskov dismissed allegations of Russian involvement as "another hoax".[29]

See also

References

- Bekus, Nelly (2010). Struggle Over Identity: The Official and the Alternative "Belarusianness". p. 4.

- https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2014/03/21/292456952/former-white-house-official-putin-wants-new-russian-empire

- Beissinger, Mark R. (2006). "Soviet Empire as 'Family Resemblance'". Slavic Review. 65 (2): 294–303.

Dave, Bhavna (2007). Kazakhstan: Ethnicity, Language and Power. Abingdon, New York: Routledge. - Caroe, O. (1953). "Soviet Colonialism in Central Asia". Foreign Affairs. 32 (1): 135–144. doi:10.2307/20031013. JSTOR 20031013.

- Tsvetkova, Natalia (2013). Failure of American and Soviet Cultural Imperialism in German Universities, 1945-1990. Boston, Leiden: Brill.

- Noren, Dag Wincens (1990). The Soviet Union and eastern Europe : considerations in a political transformation of the Soviet bloc. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Amherst. pp. 27–38.

- Ellman, Michael; Maksudov, S. (1 January 1994). "Soviet deaths in the great patriotic war: A note". Europe-Asia Studies. 46 (4): 671–680. doi:10.1080/09668139408412190. ISSN 0966-8136. PMID 12288331.

- Trenin, Dmitri (2011). Post-Imperium: A Eurasian Story. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. p. 144–145.

- "Виталий Лейбин: Экономическая экспансия России и имперский госзаказ - ПОЛИТ.РУ" (in Russian). Politic. Retrieved 20 April 2019.

- Cornis-Pope, Marcel (2004). History of the Literary Cultures of East-Central Europe: Junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th centuries. John Benjamins. pp. 29. ISBN 978-90-272-3452-0.

- Dawson, Andrew H. (1986). Planning in Eastern Europe. Routledge. p. 295. ISBN 978-0-7099-0863-0.

- 『북한 사회주의헌법의 기본원리: 주체사상』(2010년, 법학연구) pp. 13-17

- Shin, Gi-Wook (2006). Ethnic Nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, Politics, and Legacy. Stanford University Press. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-8047-5408-8.

- Crockatt, Richard (1995). The Fifty Years War: The United States and the Soviet Union in World Politics. London and New York City, New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-10471-5.

- Friedman, Jeremy (2015). Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World.

- https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/25/magazine/russia-united-states-world-politics.html

- "The Empire Strikes Out: Imperial Russia, "National" Identity, and Theories of Empire" (PDF).

- "Finns Worried About Russian Border".

- Khotin, Rostyslav (26 November 2009). "Ukraine tears down controversial statue". BBC Ukrainian Service. BBC News. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- Motyl, Alexander J. (28 April 2015). "Decommunizing Ukraine". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- Poroshenko signed the laws about decomunization. Ukrayinska Pravda. 15 May 2015

Poroshenko signs laws on denouncing Communist, Nazi regimes, Interfax-Ukraine. 15 May 2015 - Shevchenko, Vitaly (14 April 2015). "Goodbye, Lenin: Ukraine moves to ban communist symbols". BBC News. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- (in Ukrainian) In Ukraine rename 22 cities and 44 villages, Ukrayinska Pravda (4 June 2015)

- (in Ukrainian) Komsomolsk in any case be renamed, depo.ua (1 October 2015)

- Decommunization reform: 25 districts and 987 populated areas in Ukraine renamed in 2016, Ukrinform (27 December 2016)

- Troianovski, Anton (21 April 2019). "Comedian Volodymyr Zelensky unseats incumbent in Ukraine's presidential election, exit poll shows". The Washington Post. Retrieved 22 April 2019.

- "Thousands protest Ukraine leader's peace plan".

- https://peacemaker.un.org/ukraine-minsk-implementation15

- "Prague district mayor says he is under police protection against Russian threat". Reuters. 29 April 2020.

Notelist

- Following the Soviet–Albanian split (1955–1961) and the Sino–Albanian split (1972–1978).

- After Nicolae Ceauşescu's refusal to participate in the Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968.

- With the Soviet intervention in the Angolan Civil War.

- Following the Sino-Soviet split (1956–1961).

- After Chinese intervention in the Korean War in 1950, North Korea remained a Soviet ally,[13] but rather used the Juche ideology to balance Chinese and Soviet influence, pursuing a highly isolationist foreign policy and not joining the Comecon or any other international organization of communist states following the withdrawal of Chinese troops in 1958.

- At the outbreak of the Somali invasion of Ethiopia in 1977, the Soviet Union ceased to support Somalia, with the corresponding change in rhetoric. In turn, Somalia broke diplomatic relations with the Soviet Union and the United States adopted Somalia as a Cold War ally.[14]

- It was annexed by Soviet Union in 1944.

- Unlike other countries and although leaning towards the Soviet side, Vietnam's domestic policy and foreign policy were not dominated by Soviet Union.

- It ended affiliation with the Soviet Union in 1948 due to Tito–Stalin split. After Joseph Stalin's death and the repudiation of his policies by Nikita Khrushchev, peace was made with Josip Broz Tito and Yugoslavia re-admitted into the international brotherhood of socialist states, although relations between the two countries were never completely rebuilt. See also the Informbiro period.

- Due to the Cambodian–Vietnamese War.

- Withdrew from the CIS after the Russo–Georgian War.

- Permanent neutrality declared since 1995 and is recognized by the United Nations.

- Withdrew from the CIS structures in 2018 after the War in Donbass.

- Supported by Armenia

- Evo Morales was an ally of Venezuela and Cuba from 2006 until his removal in 2019.

- See Bulgaria–Russia relations

- Part of the Russia–Syria–Iran–Iraq coalition

- See Russia–Serbia relations

- See Russia–Venezuela relations

Further reading

- Crozier, Brian. The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Empire (1999), long detailed popular history.

- Dallin, David J. Soviet Russia and the Far East (1949) online on China and Japan.

- Friedman, Jeremy. Shadow Cold War: The Sino-Soviet Competition for the Third World (2015).

- Librach, Jan. The Rise of the Soviet Empire: A Study of Soviet Foreign Policy (Praeger, 1965) online free, a scholarly history.

- Nogee, Joseph L. and Robert Donaldson. Soviet Foreign Policy Since World War II (4th ed. 1992).

- Service, Robert. Comrades! A history of world communism (2007).

- Ulam, Adam B. Expansion and Coexistence: Soviet Foreign Policy, 1917–1973, 2nd ed. (1974), a standard scholarly history online free.

- Zubok, Vladislav M. A Failed Empire: The Soviet Union in the Cold War from Stalin to Gorbachev (2007) excerpt and text search.