Prolidase deficiency

Prolidase deficiency (PD) is an extremely uncommon autosomal recessive disorder associated with collagen metabolism[1] that affects connective tissues and thus a diverse array of organ systems more broadly, though it is extremely inconsistent in its expression.

| Prolidase deficiency | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Hyperimidodipeptiduria |

| |

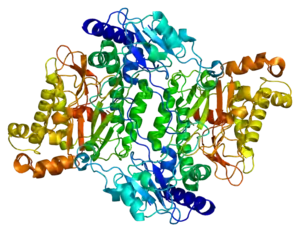

| Structure of functional prolidase enzyme, based on PDB data. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

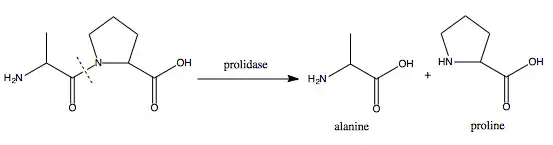

Collagen is a structural protein found i.a. in bone, skin and connective tissues that is broken down into iminodipeptides at the end of its lifecycle. Of these dipeptides, those containing C-terminal proline or hydroxyproline would normally be broken down further by the enzyme Prolidase, recovering and thus recycling the constituent amino acids.

Due to a genetic defect, prolidase activity in individuals with PD is either knocked out or severely reduced. Those affected therefore eliminate excessive amounts of iminodipeptides in their urine,[2] wasting this precious resource, with debilitating effects.

Symptoms

Prolidase deficiency generally becomes evident during infancy, but initial symptoms can first manifest anytime from birth to young adulthood. The condition results in a very diverse set symptoms,[3] the severity of which can vary significantly between patients, depending on the degree to which prolidase activity is hampered by the individual underlying mutation(s) in each case. It is even possible, though rare, for affected individuals to be asymptomatic, in which case the disorder can only be identified through laboratory screening of the prospective patient and/or their extended family.

One of the signature features of PD is the elimination of high quantities of peptides through urine.

In addition, most of those affected exhibit persistent skin lesions (starting from a mild rash) or ulcers, primarily on the legs and feet, the formation of which normally begins during childhood.[3] Clinically, these, among other dermatological issues, represent the most distinguishing and most frequent symptoms.[4] These may never recede, potentially leading to severe infections that can, in the worst case, necessitate amputation.

PD patients exhibit a weak immune system and markedly elevated vulnerability to infections in general, and particularly those of the respiratory system, leading some who suffer from PD to acquire recurrent lung disease. They may also have an enlarged spleen (splenomegaly), and on some occasions the spleen and liver may both be enlarged (hepatosplenomegaly).[3] Photosensitivity and hyperkeratosis have been associated with PD. Abnormal facial characteristics, consisting of pronounced eyes which are spaced far apart (hypertelorism), a high forehead, a compressed bridge of the nose or saddle nose, and a small lower jaw and chin (micrognathia), are also observed in the majority of cases.[3]

Those affected by PD can also suffer intellectual disabilities (approx. 75% of recorded cases do) ranging from mild to severe – mental development during childhood may therefore progress more slowly.

Causes and Genetics

Prolidase deficiency is the result of mutations on the PEPD gene, located on chromosome 19 and coding for the prolidase Enzyme, also known as peptidase-D.[3] At least 19 different mutations in the PEPD gene have been identified in individuals affected by the disorder.[5]

Prolidase is involved in the degradation of certain iminodipeptides (those containing C-terminal proline or hydroxyproline) formed during the breakdown of collagen, recycling the constituent amino acids (proline and hydroxyproline) and making them available for the cell to reuse – not least in the synthesis of new collagen. This recycling by prolidase, seen in the image above, is essential for maintaining proline-based systems in the cell, such as the collagen-rich extracellular matrix (ECM), which serves to physically support the structure of internal organs and connective tissues. Inadequate recycling due to a dysfunctional prolidase enzyme, caused by an appropriate mutation in the pertinent gene, leads to the deterioration of that support structure and therefore the connective tissue of the skin, capillaries, and the lymphatic tissue, as is the case in PD.

In particular, it has been proposed that the buildup of non-degraded dipeptides might induce programmed cell-death (apoptosis), whereafter the cell's contents would be expelled into the neighbouring tissue potentially resulting in inflammation and giving rise to the dermatological problems seen in PD. Similarly, a dysfunctional collagen metabolism will likely interfere with physiological remodelling processes of the extracellular matrix (which require collagen to be dynamically degraded and rebuilt), which might cause problems with the skin, as well.

The mental impairment observed in those with PD might reasonably arise from complications involving neuropeptides, proteins that have an abundance of proline and are involved with communication in the brain.

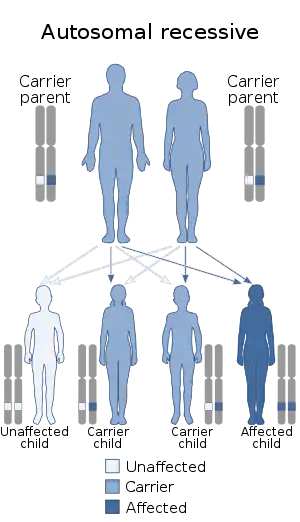

The condition is inherited in an autosomal recessive fashion, meaning that both copies of the gene contained in every cell (both alleles) are mutated. Each of the parents of the person who suffers from an autosomal recessive disorder possesses one copy of the mutant gene, but they usually do not exhibit the signs and symptoms of the disorder, as their other copy is functional and can compensate for any deleterious effects.[3]

Diagnosis

PD diagnosis is based primarily on the presence and position of ulcers on the skin, as well as identifying particular protein markers in urine. To confirm the diagnosis, a blood test is required to measure prolidase activity.

Treatment

No curative treatment is available for prolidase deficiency at this time, although palliative treatment is possible to some extent.

The latter mainly focuses on treating the skin lesions through standard methods and stalling collagen degradation (or boosting prolidase performance, where possible), so as to keep the intracellular dipeptide levels low and give the cells time to resynthesise or absorb what proline they cannot recycle so as to be able to rebuild what collagen does degrade. Patients can be treated orally with ascorbate (a.k.a. vitamin C, a cofactor of prolyl hydroxylase, an enzyme that hydroxylates proline, increasing collagen stability), manganese (a cofactor of prolidase), suppression of collagenase (a collagen degrading enzyme), and local applications of ointments that contain L-glycine and L-proline. The response to the treatment is inconsistent between affected individuals.[6]

A therapeutic approach based on enzyme replacement (administering functional prolidase) is under consideration.[7]

Due to the weakened immune response in PD cases, it is also of paramount importance to keep any infections under control, often with heavy antibiotics.

References

- Theriot, CM (2009). "Biotechnological applications of recombinant microbial prolidases". Adv Appl Microbiol. 68: 99–132. doi:10.1016/S0065-2164(09)01203-9. PMID 19426854.

- Saudubray, Jean-Marie. "Prolidase Deficiency" (PDF). Orpha Net. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- "Prolidase Deficiency". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- Andrews, James. "Prolidase Defiency". MD Consult. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- "PEPD". Genetics Home Reference. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- "Prolidase Deficiency" (PDF). Climb National Information Centre for Metabolic Diseases. Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- Viglio S, Annovazzi L, Conti B, Genta I, Perugini P, Zanone C, Casado B, Cetta G, Iadarola P (Feb 2006). "The role of emerging techniques in the investigation of prolidase deficiency: from diagnosis to the development of a possible therapeutical approach". Journal of Chromatography B. 832 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1016/j.jchromb.2005.12.049. PMID 16434239.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |