Maple syrup urine disease

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is an autosomal recessive[1] metabolic disorder affecting branched-chain amino acids. It is one type of organic acidemia.[2] The condition gets its name from the distinctive sweet odor of affected infants' urine, particularly prior to diagnosis and during times of acute illness.[3]

| Maple syrup urine disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Branched-chain ketoaciduria |

| |

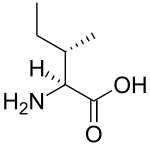

| Isoleucine (pictured above), leucine, and valine are the branched-chain amino acids that build up in MSUD. | |

| Specialty | Medical genetics |

Classification

Maple syrup urine disease can be classified by its pattern of signs and symptoms, or by its genetic cause. The most common and severe form of this disease is the classic type, which appears soon after birth, and as long as it remains untreated, gives rise to progressive and unremitting symptoms. Variant forms of the disorder may become apparent only later in infancy or childhood, with typically less severe symptoms that may only appear during times of fasting, stress or illness, but still involve mental and physical problems if left untreated.

Sub-divisions of MSUD:

- Classic MSUD

- Intermediate MSUD

- Intermittent MSUD

- Thiamine-responsive MSUD

Generally, majority of patients will be classified into one of these four categories but some patients affected by MSUD do not fit the criteria for the listed sub-divisions and will be deemed unclassified MSUD.[4]

Signs and symptoms

The disease is named for the presence of sweet-smelling urine, similar to maple syrup, when the person goes into metabolic crisis. Along with the smell being present in ear wax of an affected individual during metabolic crisis. In populations to whom maple syrup is unfamiliar, the aroma can be likened to fenugreek, and fenugreek ingestion may impart the aroma to urine.[5] Symptoms of MSUD varies between patients and is greatly related to the amount of residual enzyme activity.

Classic MSUD

Infants with classic MSUD will display subtle symptoms within the first 24–48 hours. Subtle symptoms include poor feeding, either bottle or breast, lethargy, and irritability. The infant will then experience increased focal neurologic signs. These neurologic signs include athetoid, hypertonia, spasticity, and opisthotonus that lead to convulsions and coma. If MSUD is left untreated, central neurologic function and respiratory failure will occur and lead to death. Although MSUD can be stabilized, there are still threats of metabolic decompensation and loss of bone mass that can lead to osteoporosis, pancreatitis, and intracranial hypertension. Additional signs and symptoms that can be associated with classic MSUD include intellectual limitation and behavioral issues.[4]

Intermediate MSUD

Intermediate MSUD has greater levels of residual enzyme activity than classic MSUD. The majority of children with intermediate MSUD are diagnosed between the ages of 5 months and 7 years. Symptoms associated with classic MSUD also appear in intermediate MSUD.[4]

Intermittent MSUD

Contrary to classic and intermediate MSUD, intermittent MSUD individuals will have normal growth and intellectual development. Symptoms of lethargy and characterized odor of maple syrup will occur when the individual experiences stress, does not eat, or develops an infection. Metabolic crisis leading to seizures, coma, and brain damage is still a possibility.[4]

Thiamine-response MSUD

Symptoms associated with thiamine-response MSUD are similar to intermediate MSUD. Newborns rarely present with symptoms.[4]

Later onset

The symptoms of MSUD may also present later depending on the severity of the disease.[5] Untreated in older individuals, and during times of metabolic crisis, symptoms of the condition include uncharacteristically inappropriate, extreme or erratic behaviour and moods, hallucinations, lack of appetite, weight loss,[5] anemia, diarrhea, vomiting, dehydration, lethargy,[5] oscillating hypertonia and hypotonia,[5] ataxia,[5] seizures,[5] hypoglycaemia, ketoacidosis, opisthotonus, pancreatitis,[6] rapid neurological decline, and coma.[5] Death from cerebral edema will likely occur if there is no treatment.[5] Additionally, MSUD patients experience an abnormal course of diseases in simple infections that can lead to permanent damage.

Causes

Mutations in the following genes cause maple syrup urine disease:

- BCKDHA (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 608348)

- BCKDHB (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 248611)

- DBT (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 248610)

- DLD (Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): 238331)

These four genes produce proteins that work together as the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex. The complex is essential for breaking down the amino acids leucine, isoleucine, and valine. These are present in some quantity in almost all kinds of food, but in particular, protein-rich foods such as dairy products, meat, fish, soy, gluten, eggs, nuts, whole grains, seeds, avocados, algae, edible seaweed, beans, and pulses. Mutation in any of these genes reduces or eliminates the function of the enzyme complex, preventing the normal breakdown of isoleucine, leucine, and valine. As a result, these amino acids and their by-products build up in the body. Because high levels of these substances are toxic to the brain and other organs, this accumulation leads to the serious medical problems associated with maple syrup urine disease.

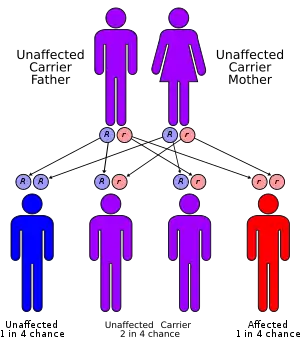

This condition has an autosomal recessive inheritance pattern, which means the defective gene is located on an autosome, and two copies of the gene – one from each parent – must be inherited to be affected by the disorder. The parents of a child with an autosomal recessive disorder are carriers of one copy of the defective gene, but are usually not affected by the disorder.

Pathophysiology

MSUD is a metabolic disorder caused by a deficiency of the branched-chain alpha-keto acid dehydrogenase complex (BCKAD), leading to a buildup of the branched-chain amino acids (leucine, isoleucine, and valine) and their toxic by-products (ketoacids) in the blood and urine.The buildup of these BCAAS will lead to the maple syrup odor that is associated with MSUD. The BCKAD complex begins by breaking down leucine, isoleucine, and valine through the use of branch-chain aminotransferase into their relevant α-ketoacids. The second step involves the conversion of α-ketoacids into acetoacetate, acetyl-CoA, and succinyl-CoA through oxidative decarboxylation of α-ketoacids. The BCKAD complex consists of four subunits designated E1α, E1β, E2, and E3. The E3 subunit is also a component of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and oxoglutarate dehydrogenase complex.[7] MSUD can result from mutations in any of the genes that code for these enzyme subunits, E1α, E1β, E2, and E3. Mutations of these enzyme subunits will lead to the BCKAD complex unable to break down leucine, isoleucine, and valine. The levels of these branched chain amino acids will become elevated and lead to the symptoms associated with MSUD. Glutamate levels are maintained in the brain by BCAA metabolism functions and if not properly maintained can lead to neurological problems that are seen in MSUD individuals. High levels of leucine has also been shown to affect water homeostasis within subcortical gray matter leading to cerebral edema, which occurs in MSUD patients if left untreated.

Diagnosis

Prior to the easy availability of plasma amino acid measurement, diagnosis was commonly made based on suggestive symptoms and odor. Affected individuals are now often identified with characteristic elevations on plasma amino acids which do not have the characteristic odor.[5] The compound responsible for the odor is sotolon (sometimes spelled sotolone).[6]

On 9 May 2014, the UK National Screening Committee (UK NSC) announced its recommendation to screen every newborn baby in the UK for four further genetic disorders as part of its NHS Newborn Blood Spot Screening programme, including maple syrup urine disease.[8] The disease is estimated to affect 1 out of 185,000 infants worldwide and its frequency increases with certain heritages.[3]

Newborn screening for maple syrup urine disease involves analyzing the blood of 1–2 day-old newborns through tandem mass spectrometry. The blood concentration of leucine and isoleucine is measured relative to other amino acids to determine if the newborn has a high level of branched-chain amino acids. Once the newborn is 2–3 days old the blood concentration of branched-chain amino acids like leucine is greater than 1000 μmol/L and alternative screening methods are used. Instead, the newborn's urine is analyzed for levels of branched-chain alpha-hydroxyacids and alpha-ketoacids.[6]

The amount and type of enzyme activity in an affected individual with MSUD will determine which classification the affected individual will identify with.

Classic MSUD: Less than 2% of normal enzyme activity

Intermediate MSUD: 3-8% normal enzyme activity

Intermittent MSUD: 8-15% of normal enzyme activity

Thiamine-Responsive MSUD: Large doses of thiamine will increase enzyme activity.[9]

Prevention

There are no methods for preventing the manifestation of the pathology of MSUD in infants with two defective copies of the BCKD gene. However, genetic counselors may consult with couples to screen for the disease via DNA testing. DNA testing is also available to identify the disease in an unborn child in the womb.[10]

Treatment

Monitoring

Keeping MSUD under control requires careful monitoring of blood chemistry, both at home and in a hospital setting. DNPH or specialised dipsticks may be used to test the patient's urine for ketones (a sign of metabolic decompensation), when metabolic stress is likely or suspected. Fingerstick tests are performed regularly and sent to a laboratory to determine blood levels of leucine, isoleucine, and valine. Regular metabolic consultations, including blood-draws for full nutritional analysis, are recommended; especially during puberty and periods of rapid growth. MSUD management also involves a specially tailored metabolic formula, a modified diet, and lifestyle precautions such as avoiding fatigue and infections, as well as consuming regular, sufficient calories in proportion to physical stress and exertion. Without sufficient calories, catabolism of muscle protein will result in metabolic crisis. Those with MSUD must be hospitalised for intravenous infusion of sugars and nasogastric drip-feeding of formula, in the event of metabolic decompensation, or lack of appetite, diarrhea or vomiting. Food avoidance, rejection of formula and picky eating are all common problems with MSUD. Some patients may need to receive all or part of their daily nutrition through a feeding tube.

Diet control

A diet with carefully controlled levels of the amino acids leucine, isoleucine, and valine must be maintained at all times in order to prevent neurological damage. Since these three amino acids occur in all natural protein, and most natural foods contain some protein, any food intake must be closely monitored, and day-to-day protein intake calculated on a cumulative basis, to ensure individual tolerance levels are not exceeded at any time. As the MSUD diet is so protein-restricted, and adequate protein is a requirement for all humans, tailored metabolic formula containing all the other essential amino acids, as well as any vitamins, minerals, omega-3 fatty acids and trace elements (which may be lacking due to the limited range of permissible foods), are an essential aspect of MSUD management. These complement the MSUD patient's natural food intake to meet normal nutritional requirements without causing harm.[11] If adequate calories cannot be obtained from natural food without exceeding protein tolerance, specialised low protein products such as starch-based baking mixtures, imitation rice and pasta may be prescribed, often alongside a protein-free carbohydrate powder added to food and/or drink, and increased at times of metabolic stress. MSUD patients with thiamine- responsive MSUD can have a higher protein intake diet with administration of high doses of thiamine, a cofactor of the enzyme that causes the condition. The typical dosage amount of thiamine-responsive MSUD depends on the enzyme activity present and can range from 10 mg - 100 mg daily.

Liver transplantation

Usually MSUD patients are monitored by a dietitian. Liver transplantation is a treatment option that can completely and permanently normalise metabolic function, enabling discontinuation of nutritional supplements and strict monitoring of biochemistry and caloric intake, relaxation of MSUD-related lifestyle precautions, and an unrestricted diet. This procedure is most successful when performed at a young age, and weaning from immunosuppressants may even be possible in the long run. However, the surgery is a major undertaking requiring extensive hospitalisation and rigorous adherence to a tapering regimen of medications. Following transplant, the risk of periodic rejection will always exist, as will the need for some degree of lifelong monitoring in this respect. Despite normalising clinical presentation, liver transplantation is not considered a cure for MSUD. The patient will still carry two copies of the mutated BKAD gene in each of their own cells, which will consequently still be unable to produce the missing enzyme. They will also still pass one mutated copy of the gene on to each of their biological children. As a major surgery the transplant procedure itself also carries standard risks, although the odds of its success are greatly elevated when the only indication for it is an inborn error of metabolism. In absence of a liver transplant, the MSUD diet must be adhered to strictly and permanently. However, in both treatment scenarios, with proper management, those afflicted are able to live healthy, normal lives without suffering the severe neurological damage associated with the disease.

Pregnancy

Control of metabolism is vital during pregnancy of women with MSUD. To prevent detrimental abnormalities in development of the embryo or fetus, dietary adjustments should be made and plasma amino acid concentrations of the mother should be observed carefully and frequently. Amino acid deficiency can be detected through fetal growth, making it essential to monitor development closely.[6]

Prognosis

If left untreated, MSUD will lead to death due to central neurological function failure and respiratory failure. Early detection, diet low in branched-chain amino acids, and close monitoring of blood chemistry can lead to a good prognosis with little or no abnormal developments. Even with proper treatment, metabolic crisis is still likely to occur and can lead to death without immediate medical treatment.

Epidemiology

Maple syrup urine disease (MSUD) is a rare, inherited metabolic disorder. Its prevalence in the United States population is approximately 1 newborn out of 180,000 live births. However, in populations where there is a higher frequency of consanguinity, such as the Mennonites in Pennsylvania or the Amish, the frequency of MSUD is significantly higher at 1 newborn out of 176 live births. In Austria, 1 newborn out of 250,000 live births inherits MSUD.[12] It also is believed to have a higher prevalence in certain populations due in part to the founder effect[13] since MSUD has a much higher prevalence in children of Amish, Mennonite, and Jewish descent.[14][15][16]

Research directions

Gene therapy

Gene therapy to overcome genetic mutations cause MSUD has already been proven safe in animals studies with MSUD. The gene therapy involves a healthy copy of the gene causing MSUD is produced and inserted into a viral vector. The adeno-associated virus vector is delivered one-time to the patient intravenously. Hepatocytes will take up vector and functional copies of the affected gene is MSUD patients will be expressed. This will allow BCAA to be broken down properly and prevent toxic build up.[17]

Phenylbutyrate therapy

Sodium phenylacetate/benzoate or sodium phenylbutyrate has been shown to reduce BCAA in a clinical trial done February 2011. Phenylbutyrate treatment reduced the blood concentration of BCAA and their corresponding BCKA in certain groups of MSUD patients and may be a possible adjunctive treatment.[18]

References

- Podebrad F, Heil M, Reichert S, Mosandl A, Sewell AC, Böhles H (April 1999). "4,5-dimethyl-3-hydroxy-25H-furanone (sotolone)--the odour of maple syrup urine disease". Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 22 (2): 107–114. doi:10.1023/A:1005433516026. PMID 10234605. S2CID 6426166.

- Ogier de Baulny H, Saudubray JM (2002). "Branched-chain organic acidurias". Semin Neonatol. 7 (1): 65–74. doi:10.1053/siny.2001.0087. PMID 12069539.

- "Maple syrup urine disease". Genetics Home Reference. July 2017.

- "NORD - Maple Syrup Urine Disease". Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- "OMIM Entry - # 248600 - MAPLE SYRUP URINE DISEASE; MSUD". www.omim.org. Retrieved 2016-11-14.

- Strauss, Kevin A.; Puffenberger, Erik G.; Morton, D. Holmes (1993-01-01). Pagon, Roberta A.; Adam, Margaret P.; Ardinger, Holly H.; Wallace, Stephanie E.; Amemiya, Anne; Bean, Lora J.H.; Bird, Thomas D.; Fong, Chin-To; Mefford, Heather C. (eds.). Maple Syrup Urine Disease. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle. PMID 20301495.

- Pasquali, Marzia; Longo, Nicola (December 13, 2011). "58. Newborn screening and inborn errors of metabolism". In Burtis, Carl A.; Ashwood, Edward R.; Bruns, David E. (eds.). Tietz Textbook of Clinical Chemistry and Molecular Diagnostics (5th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 2062. ISBN 978-1-4160-6164-9.

- "New screening will protect babies from death and disability". screening.nhs.uk.

- "MSUD classifications".

- "Maple Syrup Urine Disease (MSUD)". Healthline. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- Hallam P, Lilburn M, Lee PJ (2005). "A new protein substitute for adolescents and adults with maple syrup urine disease (MSUD)". J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 28 (5): 665–672. doi:10.1007/s10545-005-0061-6. PMID 16151896. S2CID 24718350.

- "Maple Syrup Urine Disease (MSUD): Facts & Information". Disabled World. Retrieved 2016-11-10.

- Jaworski MA, Severini A, Mansour G, Konrad HM, Slater J, Henning K, Schlaut J, Yoon JW, Pak CY, Maclaren N, et al. (1989). "Genetic conditions among Canadian Mennonites: evidence for a founder effect among the old country (Chortitza) Mennonites". Clin Invest Med. 12 (2): 127–141. PMID 2706837.

- Mary Kugler, R.N. "Maple Syrup Urine Disease". About.com Health.

- Puffenberger EG (2003). "Genetic heritage of Old Order Mennonites in southeastern Pennsylvania". Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 121 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.20003. PMID 12888983. S2CID 25317649.

- "Maple Syrup Urine Disease (MSUD) - Jewish Genetic Disease". Retrieved 18 December 2015.

- "MSUD infographic - gene therapy". Retrieved 13 December 2019.

- Brunetti-Pierri, Nicola; Lanpher, Brendan; Erez, Ayelet; Ananieva, Elitsa A.; Islam, Mohammad; Marini, Juan C.; Sun, Qin; Yu, Chunli; Hegde, Madhuri; Li, Jun; Wynn, R. Max; Chuang, David T.; Hutson, Susan; Lee, Brendan (15 February 2011). "Phenylbutyrate therapy for maple syrup urine disease". Hum Mol Genet. 20 (4): 631–640. doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq507. PMC 3024040. PMID 21098507.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Maple syrup urine disease at NLM Genetics Home Reference

- msud at NIH/UW GeneTests