Purple Line (Maryland)

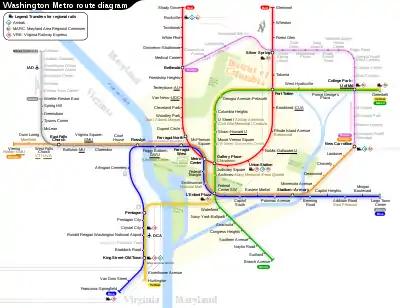

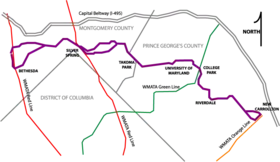

The Purple Line is a planned 16.2-mile (26.1 km) light rail line[3] intended to link the Maryland suburbs of Bethesda, Silver Spring, College Park, and New Carrollton, all in the Washington metropolitan area.[7] The line will allow riders to move between the Maryland branches of the Red, Green/Yellow, and Orange lines of the Washington Metro without needing to ride into central Washington, D.C., and will also offer transfers to all three lines of the MARC commuter rail system. Contrary to popular belief, and similarity of the name to some of the Metrorail lines, the project is being administered by the Maryland Transit Administration (MTA), an agency of the Maryland Department of Transportation, and not the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA/Metro).

Purple Line Transit Partners, a consortium headed by Fluor Enterprises, was formed to design and build the Purple Line, and subsequently operate and maintain it for 36 years.[8][3] Construction began in August 2017.[9] Work on the line ceased in September 2020, with the consortium intending to terminate its contract due to mounting delays and leaving the project incomplete without a general contractor.

Throughout the decades-long planning process, the project had been dogged by resistance, particularly from inhabitants of the upscale community of Chevy Chase. During the administration of Governor Bob Ehrlich plans were made to build a bus rapid transit line dubbed the Bi-County Transitway instead. Legal attempts to thwart the line continued even after construction had begun;[10] but in December 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled that Purple Line construction could continue despite these objections.[11][12]

History

Early studies, public debate, design

The "Purple Line" has been the name of two different transit proposals. In 1994, John J. Corley Jr., an architect with Harry Weese Associates (which designed the Washington Metro system) proposed a multibillion-dollar Metro line around the 64-mile (103 km) Capital Beltway. This would have served as a "ring" line, connecting suburb to suburb, as compared to the lines of the existing Metro system, which radiate from Washington.[13] (See Rapid transit#Network topologies.) In 1998, the Beltway Purple Line received considerable political support from Montgomery County Executive Douglas M. Duncan and then-Governor Parris Glendening, which was a $10 billion, 30-mile (48 km) line from National Harbor to Montgomery Mall.[14]

In 1987, after CSX expressed a desire to abandon the Georgetown Branch rail line, Maryland leaders immediately started planning to repurpose it for transit and a hiking trail.[15] The idea of adapting the railroad for a transit line dated back at least as far as 1970, when such a use was included in the October 1970 Master Plan for the Bethesda-Chevy Chase Planning Area.[16] Montgomery County purchased its portion of the railroad right-of-way from CSX in 1988.[17] Eventually, this proposal came known as the "Inner Purple Line" to distinguish it from the "Beltway Purple Line". By 2001, the "Beltway Purple Line" proposal had been abandoned as too costly and the name was attached to the Bethesda to New Carrollton line.[18]

Robert Flanagan, the Maryland State Secretary of Transportation under Governor Robert Ehrlich, merged the Purple Line proposal with the Georgetown Branch Light Rail Transit (GBLRT). The GBLRT was proposed as a light rail transit line from Silver Spring westward, following the former Georgetown Branch of the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad (now a short CSX siding and the Capital Crescent Trail) to Bethesda.[19]

.jpg.webp)

Both Governor Ehrlich and Secretary Flanagan introduced an alternative mode – bus rapid transit – that might have been utilized in lieu of light rail transit. To reflect this possibility, the administration changed the name of the project to the "Bi-County Transitway" in March 2003. Another reason that the "Purple Line" was discouraged by the Ehrlich administration was that its associations with the other color-oriented names of the Washington Metro system (which consists of heavy rail) might lead the public to expect a heavy rail option. The new name did not catch on, however, as several media outlets and most citizens continued to refer to the project as the Purple Line. As a result, Governor Martin O'Malley and Secretary of Transportation John Porcari opted to revert to "Purple Line" in 2007.[21]

In January 2008, the O'Malley administration allocated $100 million within a six-year capital budget to complete design documents for state approval and funding of the Purple Line.[22] In May 2008, it was projected that the Purple Line would have about 68,000 daily trips.[23]

A draft environmental impact study was issued on October 20, 2008.[24] On December 22, 2008, Montgomery County planners endorsed building a light rail line rather than a bus line. On January 15, 2009, the county planning board also endorsed the light rail option,[25] and County Executive Isiah Leggett has also expressed support.[26] On October 21, 2009, members of the National Capital Region Transportation Planning Board voted unanimously to approve the Purple Line light rail project for inclusion into the region's Constrained Long-Range Transportation Plan.[27]

Planners intend to utilize existing Washington Metro stations and to accept the WMATA's SmarTrip farecard.[28] Metro's 2008 annual report envisioned that the Purple Line would be fully integrated with the existing Washington Metro transit system by 2030.[29][30]

The proposed project prompted support and opposition in the community:

Support for Purple Line

- Purple Line Now is a non-profit advocating for the inside the beltway light rail Purple Line from Bethesda to New Carrollton to integrated with a hiker/biker trail from Bethesda to Silver Spring.[31]

- The Action Committee for Transit is a community group that supports the Purple Line.[32]

- The Washington Post editorial board endorsed the Purple Line light rail option in 2008.[33]

- The Montgomery County Council and Prince George's County Council voted unanimously in favor of the light rail option for the Purple Line in January 2009.[34]

- Maryland state officials (including former Governor Martin O'Malley, D-MD) are also strong Purple Line advocates. State officials say that a Purple Line, which would run primarily above ground, "would provide better east–west transit service, particularly for lower-income workers who cannot afford cars."[35]

- The development firm Chevy Chase Land Co. is a strong proponent of the construction of the Purple Line. The website for the pro-Purple umbrella group Purple Line NOW! lists Edward Asher as a member of its board of directors. The Washington Post indicates that the development firm would "no doubt profit from property it owns near at least one of the proposed stations."[35]

- The Sierra Club advocates a larger-scale rail system to parallel the Capital Beltway and link all existing Metro lines at their peripheries. This environmental group advocates rail transit over car use because carbon emissions are a major risk factor for global warming.[36]

- Some student leaders (the Student Government Association and Graduate Student Government) at the University of Maryland support transit alternatives to campus.[37][38]

- On January 27, 2009, the Montgomery County Council voted to support the light rail option.[39] Governor O'Malley announced his own approval on August 4, 2009.[1]

- The vice president of trail development for the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy has gone on record citing rail-trail combinations around the country and arguing that with proper design, the trail-purple-line combination can be "among the best in the nation." [40]

- Members of the Facebook group New Urbanist Memes for Transit-Oriented Teens were "irrationally excited for the forthcoming Maryland purple line."[41]

Support for bus

- A 2008 study by Sam Schwartz Engineering for the Town of Chevy Chase supported bus rapid transit using an alternate Jones Bridge Road alignment. The Chevy Chase study expressed concerns about the expected ridership numbers, carbon footprint, interruptions in recreation pathways, and the cost of bus and light rail proposals by the MTA involving a Capital Crescent Trail alignment. Although a Jones Bridge Road alignment was also proposed by the MTA, the study noted that features typical of bus rapid transit that were missing from the MTA proposal.[42]

Opposition to rail

- A not for profit local organization, Friends of the Capital Crescent Trail, has been collecting signatures on a petition opposing the MTA's Purple Line proposals since 2003 and filed a lawsuit in the Federal District Court in the District of Columbia in 2014 asserting failure by the Federal Transit Administration to comply with Federal environmental laws in initially approving a grant to help build the Purple Line. The organization's website explains that the MTA's light rail and bus rapid transit proposals will have significant environmental and safety impacts on the Capital Crescent Trail.[43] Alternatives suggested by the organization's website included the Jones Bridge Road alignment for bus rapid transit recommended by the Chevy Chase study.[42] Save the Trail Petition prefers alternatives, however, noting that a Jones Bridge Road alignment would also have some impact on the trail.[44]

- A leading opponent of the Purple Line was the Columbia Country Club, a golf course with land that occupies both sides of the planned route between Bethesda and Silver Spring.[45] Newly elected leaders of the Club signed an agreement not to oppose the Purple Line if its route were adjusted by 12 feet.

- Opponents in the Town of Chevy Chase cited the town's study of bus rapid transit alternatives. The study estimated a cost of less than $1 billion for a bus rapid transit system, compared with an estimated cost of $1.8 billion for light rail.[46] A 2011 news report placed the cost of the rail line at US$1.93 billion .[47]

- Residents around the Dale Wayne stop are concerned that doubling the size of the road, along with the county's "smart growth" policy around transit stops, will encourage commercial development in a residential neighborhood. Their concerns have also questioned whether the 1,427 daily boardings anticipated by the MTA by 2030 is a realistic figure for the Dale station.[48][49]

Procurement

The Purple Line was procured as a full design-build-finance-operate-maintain public–private partnership. On December 7, 2015, four teams composed of major American and international firms submitted their bids to realize the project:[50][51]

- "Maryland Purple Line Partners" composed of Vinci Concessions, Walsh Investors, InfraRed Capital, Alstom and Keolis,

- "Maryland Transit Connectors" composed of John Laing Investments, Kiewit Development Company, Edgemoor Infrastructure & Real Estate and RATP Dev,

- "Purple Line Transit Partners" composed of Meridiam, Fluor Corporation, Star America, CAF and Alternate Concepts,

- "Purple Plus Alliance" compose of Macquarie Capital Group, Skanska, Kinki Sharyo and Transdev.

Approval

.jpg.webp)

Governor Larry Hogan opposed the Purple Line project while campaigning in 2014 but approved it in June 2015. At the same time, Hogan cancelled its sister project, the Baltimore Red Line, citing excessive costs. Hogan reduced the state's contribution to the project from $700 million to $168 million, with the savings reallocated toward increased highway construction. The budget shortfall is expected to be covered by increased funds from Prince George's and Montgomery counties, as well as lower operational costs due to longer headways.[52]

On March 2, 2016, Hogan announced that the state has chosen a team of private companies to build, operate and maintain a light-rail Purple Line in the Washington suburbs for $3.3 billion over 36 years. Under the winning bid – proposed by the team Purple Line Transit Partners and led by construction giant Fluor Corporation – the six-year construction project began later that year, and the 16-mile line may be open for service by late 2022 (according to MTA officials), or else 2023 or 2024 (according to Purple Line Transit Partners).[53][54]

On April 6, 2016, the Maryland Board of Public Works – made up of Hogan, State Treasurer Nancy K. Kopp, and State Comptroller Peter Franchot – unanimously approved the contract, as expected.[55] The $5.6 billion contract is 876 pages long and, according to The Washington Post is "believed to be the most expensive government contract ever in Maryland" and "one of the largest public-private partnerships on a U.S. transportation project" ever.[55] The contract approval allows the Maryland Transit Administration to finalize $900 million in federal construction grants.[53][55]

In August 2016, U.S. District Court Judge Richard J. Leon found that the Maryland Transit Administration and the Federal Transit Administration did not study whether Metro's maintenance issues and ridership decline would affect the Purple Line.[56] Judge Leon decided to vacate the Purple Line's federal approval.[56] A federal funding agreement cannot be signed without the reinstatement of the environmental approval, and Maryland has said it cannot afford to build the Purple Line without sufficient federal funding.[56][57] On August 21, 2017, despite the ongoing court case over the environmental analysis, $900 million of federal funding was granted for the light rail project.[58] On December 19, 2017, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit ruled in favor of the Purple Line, specifically stating that declining ridership on the Washington Metro system does not require Maryland to complete a new environmental study for the Purple Line.[12] This federal appeals court ruling allowed for construction to continue and effectively ended the three-year legal battle surrounding the 16-mile light-rail line project.[11] On April 13, 2020, U.S. District Judge James Bredar dismissed the third and final lawsuit brought by opponents of the Purple Line.[59]

Purple Line Transit Partners quits

By 2020, the project had accrued over $800 million in change orders from Purple Line Transit Partners and the opening date had slipped 32 months.[60][61][62] The consortium sent a letter to the state on May 1 that year letting known their intent to cease work on the line and terminate their contract.[60] A temporary restraining order which had halted the company from quitting work was lifted in September,[63] and PLTP began packing up construction sites the following week.[64]

In November 2020, the Maryland Department of Transportation announced that MDOT and the Maryland Transit Administration have assumed many of the Purple Line’s contracts, including the manufacturing of light-rail cars, operations, and maintenance, as well as design and construction contracts.[65] On November 24, 2020, the Maryland Department of Transportation agreed to pay $250 million to settle the costs of overruns that caused the contractor to quit and to resume construction of the Purple Line.[66][67] In mid-December 2020, Maryland’s Board of Public Works officially and unanimously voted to approve the $250 million legal settlement to PLTP to resolve the contract disputes and resume construction within the next nine months.[68]

Route and station locations

The planned rail line will connect the existing Metro, MARC commuter rail, and Amtrak stations at:[7]

- Bethesda (Metro Red Line)

- Silver Spring (Metro Red Line, MARC Brunswick Line)

- College Park (Metro Green Line, Metro Yellow Line, MARC Camden Line)

- New Carrollton (Metro Orange Line, MARC Penn Line, Amtrak Northeast Regional, Amtrak Vermonter)

The following stations are part of the "Locally Preferred Alternative" route approved by Governor Martin O'Malley on August 9, 2009:[69]

| Station Name | Location | Connections | Facilities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bethesda station | 7450 Wisconsin Avenue, Bethesda, Maryland | ||

| Connecticut Avenue station | Capital Crescent Trail, Connecticut Avenue Chevy Chase, MD 20815 | ||

| Lyttonsville station | Lyttonsville Place, Lyttonsville, Silver Spring, MD 20910 | ||

| 16th Street–Woodside station | 16th Street Woodside, Silver Spring, MD 20910 | ||

| Silver Spring Transit Center | 8400 Colesville Road, Silver Spring, MD 20910 | Transit center (existing) | |

| Silver Spring Library station | 900 Wayne Avenue, Silver Spring, MD 20910 | ||

| Dale Drive station | Dale Drive and Wayne Avenue Silver Spring, MD 20910 | ||

| Manchester Place station | Wayne Avenue and Plymouth Street Silver Spring, MD 20910 | ||

| Long Branch station | 8736 Arliss St, Silver Spring, MD 20901 | ||

| Piney Branch Road station | Piney Branch Road and University Boulevard Silver Spring, MD 20903 | ||

| Takoma Langley Crossroads Transit Center | 7900 New Hampshire Ave, Langley Park, MD | ||

| Riggs Road station | Riggs Road and University Boulevard Langley Park/Hyattsville, MD 20903 | ||

| Adelphi Road–UMGC–UMD station | Adelphi Road and Campus Drive Adelphi/Hyattsville, MD 20903 | ||

| Campus Drive–UMD station | Campus Drive and Library Lane College Park, MD 20742 | ||

| Baltimore Avenue–College Park–UMD station | Baltimore Avenue and Rossborough Lane College Park, MD 20742 | ||

| College Park–University of Maryland station | 4931 Calvert Road and 7202 Bowdoin Avenue, College Park, Maryland | ||

| Riverdale Park North–UMD station | River Road and Haig Drive Riverdale, MD 20737 | ||

| Riverdale Park–Kenilworth station | East West Highway and Kenilworth Avenue Riverdale, MD 20737 | ||

| Beacon Heights–East Pines station | Riverdale Road and 67th Avenue Riverdale, MD 20737 | ||

| Glenridge station | Veterans Parkway and Annapolis Road Hyattsville, MD 20784 | ||

| New Carrollton station | 4300-4700 Garden City Drive, New Carrollton, Maryland | ||

Potential further expansion

Although the majority of discussions about the Purple Line describe the project as a 16-mile east–west line between Bethesda and New Carrollton,[7] there have been several proposals to expand the line further into Maryland or to mirror the Capital Beltway as a loop around the entire Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. The Sierra Club has argued for a Purple Line that would "encircle Washington, D.C." and "connect existing suburban metro lines."[36] Maryland Lieutenant Governor Anthony G. Brown, while campaigning in 2006, similarly stated that he would "like to see the Purple Line go from Bethesda to across the Woodrow Wilson Bridge," adding, "Let's swing that boy all the way around" (a reference to having the Purple Line circle through Virginia and back to the line's point of origin in Bethesda).[70]

An advocacy group known as "The Inner Purple Line Campaign" has stated that the Purple Line could be extended westward to Tysons Corner and eastward to Largo, and that it could eventually cross the new Wilson Bridge from Suitland through Oxon Hill to Alexandria, eventually forming a rail line that encircles the city.[32] The reconstruction of the Woodrow Wilson Bridge (I-495's southern crossing over the Potomac River) provides capacity for the bridge to carry a heavy or light rail line.[71] Suggested stops along this proposed Purple Line expansion include:[72]

- Largo Town Center

- Branch Avenue

- Oxon Hill (potentially near Rosecroft Raceway, at which Metro has at times had plans to build a stop since 1980[73])

- National Harbor

- Alexandria, potentially the King Street–Old Town Metro station

- Springfield

- Annandale

- Dunn Loring

- Tysons Corner

Rolling stock

The light rail vehicles designed to run on the Purple Line are being constructed by CAF at their Elmira, New York facility. Vehicles are 136 feet (41 m) long[74] and can carry up to 431 passengers. Cars are planned to enter the testing phase of operation in 2020.[75]

References

- "Governor O'Malley Announces Purple Line Locally Preferred Alternative" (Press release). New Carrollton, MD: MDOT. August 4, 2009. Archived from the original on September 14, 2015. Retrieved October 18, 2014.

- "CAF Awarded Supply of 26 LRVS For Maryland in the USA". June 28, 2016. Archived from the original on July 11, 2016. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- Freed, Benjamin (March 2, 2016). "Purple Line Construction to Start Later This Year". Washingtonian. Retrieved October 15, 2018.

- Request For Proposals Technical Provisions Part 2B, Design Build Requirements (Report). MDOT/MTA. pp. 2–203. Retrieved September 27, 2020.

- Shah, Dhaval R. Presale: Purple Line Transit Partners LLC. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: S&P Global Ratings. p. 14. Retrieved December 11, 2018.

- "MARYLAND LRV maximum speed". CAF. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- "Project Overview – Maryland Purple Line". purplelinemd.com. MTA. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- "Purple Line Contract Receives Green Light From Governor Larry Hogan". mymcmedia.org. March 2, 2016. Retrieved March 2, 2016.

- Shaver, Katherine (September 27, 2018). "Purple Line set to open in fall of 2022, despite year-long delay in construction start, Maryland official says". Washington Post. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- Metcaf, Andrew (December 19, 2016). "Transit Agencies Say Metro's Woes Won't Impact Purple Line". Bethesda Magazine. Retrieved January 7, 2017.

- Shaver, Katherine (December 19, 2017). "Federal appeals court ruling allows Purple Line construction to continue". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- Cloherty, Megan (December 19, 2017). "US appeals court clears a legal hurdle for Purple Line". WTOP. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- Fehr, Stephen (December 18, 1994). "A Palette of Proposals for Metro". The Washington Post.

- "A Governor's Purple Vision". The Washington Post. October 18, 1998. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2017.

- Mariano, Ann (June 13, 1987). "Study Favorable to CSX Rail Plans". The Washington Post.

- Bethesda : Central Business District Sector Plan. July 1975.

- Armao, Jo-Ann (December 9, 1988). "Rail Spur Purchase `Priceless'; Montgomery Weighs Hiking, Trolley Line". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 6, 2017.

- Layton, Lindsey (March 31, 2001). "Glendening Gives Pro-Metro Pep Talk". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 2, 2017.

- "What is the Purple Line – Maryland Purple Line". purplelinemd.com. MTA. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- "Officials Break Ground on Long-Awaited Purple Line Project; Construction Immediately Starts". Bethesda Magazine. August 28, 2017. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- "Project History – Maryland Purple Line". purplelinemd.com. MTA. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- Davis, Janel (January 18, 2008). "O'Malley allocates $100M for Purple Line planning". The Gazette. Maryland: Post-Newsweek Media. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- Shaver, Katherine (May 30, 2008). "Trips on Purple Line Rail Projected at 68,000 Daily". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- "Studies & Reports Maryland Purple Line". MTA. Retrieved July 25, 2015.

- Spivak, Miranda S. (January 16, 2009). "Montgomery Planners Back Rail". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- Shaver, Katherine (January 23, 2009). "Leggett Endorses Light-Rail Plan". The Washington Post. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- TPB News Vol XVII Issue 4 p. 1 (November 2009). "TPB Gives Final Approval to Purple Line Project" (PDF). Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- "Public Meeting on the Purple Line" (PDF). Town of Chevy Chase, Maryland. June 6, 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2013. Retrieved October 21, 2014.

- "2008 Annual Report" (PDF). Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority. Retrieved January 21, 2009.

- "Metro preparing for more people to shift to transit if gasoline prices continue to skyrocket". WMATA. May 22, 2008. Retrieved June 24, 2009.

- "Purple Line Now: Who We Are". Purple Line Now. Retrieved October 8, 2011.

- What is the Purple Line?, The Inner Purple Line Campaign, a project of the Action Committee for Transit (ACT), retrieved December 4, 2009

- "Full Speed Ahead". The Washington Post. November 16, 2008. Retrieved December 19, 2008.

- "News & Events". purplelinenow.org. Archived from the original on May 17, 2015. Retrieved January 6, 2010.

- Katherine Shaver (July 13, 2008). "Purple Line Foes Offer No Ideas, And No Names". The Washington Post. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- "Transportation (and how it relates to Smart Growth)". Sierra Club. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- Katherine Shaver (May 13, 2007). "Students Urge Stronger Backing of Purple Line". The Washington Post. p. C04.

- "Letter from student leaders to UMD President" (PDF). Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Shaver, Katherine (January 23, 2009). "Leggett Endorses Light-Rail Plan". The Washington Post. p. B03. Retrieved January 26, 2009.

- Maynard, Patrick (June 8, 2011). "Rails to Trails VP on Purple Line". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved June 19, 2011.

- Hunt, Elle (July 5, 2018). "Meet the Numtots: the millennials who find fixing public transit sexy". The Guardian. Guardian Media Group. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- "Analysis of MTA Purple Line". Sam Schwartz Engineering. April 23, 2008. Retrieved December 1, 2009.

- Save the Trail

- Save the Trail Petition: Alternatives Studies of alternatives to a Capital Crescent Trail alignment, retrieved December 2, 2009

- Katherine Shaver (January 16, 2005). "Fortunes Shift for East-West Rail Plan". The Washington Post. p. C01.

- Katherine Shaver (July 7, 2008). "Chevy Chase Says Buses Beat Trains on Purple Line". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 15, 2014.

- Luz Lazo (September 30, 2011), "In Langley Park, Purple Line brings promise, and fears, of change", The Washington Post, retrieved November 15, 2011

- Jason Tomassini (May 12, 2010). "MTA pushing for additional Purple Line stop in Silver Spring". The Gazette.

- Purple Line study report (August 2009). "An evaluation of the merits of an LRT station at Dale Drive and Wayne Avenue" (PDF). MTA Maryland. Retrieved July 13, 2010.

- Shaver, Katherine (December 8, 2015). "Four teams of private companies submit bids to build, operate Purple Line". The Washington Post.

- "Shortlisted Proposers Purple Line P3 Revised Third Party Contact Points" (PDF). Retrieved January 18, 2016.

- McCartney, Robert; Hicks, Joshua; Turque, Bill (June 25, 2015). "Hogan: Maryland will move forward on Purple Line, with counties' help". The Washington Post. Retrieved July 1, 2015.

- Shaver, Katherine (March 2, 2016). "Maryland chooses private team to build, operate light-rail Purple Line". The Washington Post. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- Neibauer, Michael (January 10, 2019). "Report: Purple Line construction delays adding $215M to price tag". Washington Business Journal.

- Katherine Shaver (April 6, 2016). "Maryland board approves $5.6 billion Purple Line contract". The Washington Post.

- Metcalf, Andrew (November 29, 2016). "Purple Line Groundbreaking on Hold Until Transit Agencies Can Find Lawsuit Solution". Bethesda Magazine. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Shaver, Katherine (March 16, 2017). "Federal money to build Purple Line in question under Trump budget plan". The Washington Post.

- Robert McCartney and Faiz Siddiqui (August 21, 2017). "Maryland to get $900-million federal full funding agreement for Purple Line". The Washington Post. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- Shaver, Katherine (April 14, 2020). "Judge dismisses third — and final — lawsuit against Purple Line project". Washington Post. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- Strupp & Barthel (June 24, 2020). "Purple Line Group Threatens To Quit If There's No Deal With Maryland On Delays, Cost Overruns". WAMU. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

The state says the eastern section, from New Carrollton to College Park, is now expected to open in late 2022 and the rest of the line, from College Park to Bethesda, will likely open in June 2023. However, PLTP has said the various delays will set the opening dates back at least another two and a half years.

- Phillips, Zachary (September 24, 2020). "Joint venture walks away from Maryland's Purple Line project". Construction Dive. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- Shaver, Katherine (July 18, 2020). "Purple Line project delays, cost overruns reveal long-brewing problems". Washington Post. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- Parsons, Jim; Rubin, Debra K. (September 11, 2020). "Court Ruling Clears P3 Team to Leave Disputed $2B Md. Purple Line Rail Project". Engineering News-Record. Retrieved September 25, 2020.

- Shaver, Katherine (September 24, 2020). "Purple Line construction workers will be packed up and ready to leave by mid-October, contractor says". The Washington Post. Retrieved September 26, 2020.

- "Pessoa Construction Performing Purple Line Utility Relocations Along Wayne Avenue". Source of the Spring. Retrieved November 6, 2020.

- Shaver, Katherine. "Maryland, Purple Line firms reach $250 million deal to keep project moving". Washington Post. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Campbell, Colin. "Maryland to pay $250 million to settle Purple Line disputes, replace construction contractor". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved November 24, 2020.

- Shaver, Katherine (December 16, 2020). "Maryland board approves $250 million legal deal to complete Purple Line construction". The Washington Post. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- "Stations – Maryland Purple Line". purplelinemd.com. MTA. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- Thomas Dennison and Douglas Tallman (October 4, 2006). "Brown's 'lofty' Purple Line plans draw fire from transportation officials". The Gazette. Retrieved December 4, 2009.

- Scott M. Kozel (February 25, 2009). "Woodrow Wilson Bridge (I-495 and I-95)". Roads to the Future. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- "Sierra Club Purple Line Map". Archived from the original on May 12, 2010.

- Scott M. Kozel (January 23, 2001). "Metrorail Branch Avenue Route Completion". Roads to the Future. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- Beckwith, Alison. "Get a Sneak Peek of the Purple Line on Route 1". The Hyattsville Wire. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- Shaver, Katherine (May 10, 2018). "Purple Line train tests will begin in Maryland in 2020 or after, contractor says". Washington Post. Retrieved July 6, 2018.

External links

- Official website

- Purple Line Montgomery County Planning Department