Roman Catholic Kshatriya

The Roman Catholic Kshatriya is a caste among the Goan and Mangalorean Catholics, of modern-day descendants of Goan Kshatriya and Vaishya converts to Roman Catholicism.[1][2][3] They are known as Chardo in the Goan Catholic dialects of Konkani[4] (Devanagari: चारड्डो), Charodi (Kannada: ಚರೋಡಿ; Tsāroḍi[1]) in the Mangalorean Catholic dialect of Konkani, and Chardó in Portuguese. They are an endogamous group and have traditionally avoided inter-marriage with Catholics of other castes.[5][6]

Chardo | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| approx 135,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Goa | 100,000 |

| Mangalore | 10,000 |

| Rest of India | 3,000 |

| Languages | |

| Konkani and Portuguese | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly: Roman Catholic | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Hindu Kshatriyas | |

Etymology

The precise etymology of the word Chardo is unclear. The two most probable explanations are as follows:[7]

- The roots of this Konkani word probably lies in the Prakrit word Chavada, which the name of a tribe of warriors who migrated to Goa from Saurashtra in the 7th and 8th centuries, after their kingdom was destroyed by the Arabs in 740 AD.[7]

- Another explanation given by historian B.D. Satoskar is that the Konkani word comes from the Sanskrit word Chatur-rathi or the Prakrit Chau-radi, which literally means "the ones who ride a chariot yoked with four horses".[7]

Origins

The Kshatriyas of Goa constituted the nobility and warrior class, and ranked second in the Hindu Varna system. Those involved in the trading profession were known as Chattim, which was an occupational appellation common to Brahmins as well.[2] The origins of a Christian caste can be traced back to the Christianisation of the Velhas Conquistas (Portuguese: Old Conquests) that was undertaken by the Portuguese during the 16th and 17th centuries.[2] It was during this period that the Jesuit, Franciscan and Dominican missionaries converted many Kshatriyas to Christianity.[8] The caste appellation of Chardo eventually fell into disuse among the Hindu Kshatriyas, who began calling themselves Maratha (Konkan Marathas), to differentiate themselves from those Kshatriyas who had embraced Christianity.[2] Another reason for the name change was because of the ascendancy of the Marathas in the political arena of the Maratha Confederacy.[2] The Marathas and Vaishya Vanis who were among the last to convert, were incorporated into the Chardo caste.[2]

The earliest known instance of Kshatriya conversions to Christianity took place in 1560, when 700 Kshatriyas were baptised en masse in Carambolim, Tiswadi. Their decision to embrace Christianity was made after deliberation of the village assembly, and came about as they were subjects of the Portuguese government.[9] Another instance of a Kshatriya group seeking conversion to Christianity is mentioned in a letter of a Jesuit missionary Luís Fróis, dated 13 November 1560:[9]

"Mass baptisms in this village (Batim in Bardez) took place on 25 August 1560. The priests who had been sent to make preparations for the christening were asleep when at midnight of the 24th (August) more than 200 persons (men, women and children) knocked at their door and declared that they wished to become Christians. The women were very well dressed and wore plenty of gold. The men were also well dressed with feathers in their caps and guns on their shoulders. This group was led by one man named Camotim (Kamat). He wore scarlet satin pants, had a silver sword at his waist and a gun on his shoulder. All of them were baptised on the above-mentioned day. These people belonged to the Chardo class, consisting of warriors, men of a much better personality than the Brahmins."

The Charodis form the second largest group in the Mangalorean Catholic community.[1] In South Canara, many Charodis took up service in the army of the Keladi Nayakas, and came to constitute the bulk of the Christian soldiers in their army. The Lewis-Naik family of Kallianpur near Udupi, produced many distinguished soldiers and officers in the Keladi army. In recognition of their service, the Nayakas rewarded them with large tracts of land in Kallianpur.[10] During the Indian independence struggle, Chardos were perceived by Indian nationalists to be more sympathetic to Indian nationalist leanings and less likely to be pro-Portuguese loyalists than Bamonns.[11] In his autobiography, Indian nationalist Eddie Pereira (himself of Chardo heritage) stated about the origins of the Chardos:[12]

"If records are to be trusted, the Chardo Kshatriya lineage had its origin in the annals of the epic narratives of the Ramayana.

Our ancestors derived their inspiration from the heroes of Raghuvamsha... We all call ourselves Chalukya Chardo Kshatriyas and so we belong to a warrior caste of the fourfold social order in ancient India... Shri Ramachandra, King of Ayodhya, is the hero of the Ramayana, one of the sacred epics of India. This Ayodhya of Ramchandra was the Chardo place of origin. Chardos are mainly found in Goa and the surrounding area out of Goa. Fallen as the Chardo Kshatriyas were from the high ideals of unity and freedom, they have in them the spirit of bravery of their indomitable ancestors. They never held their personal life dear, but welcomed even death in the later years of their struggle.

Yet they had to migrate from place to place to keep their tradition, culture and the way of life intact."

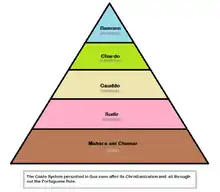

The Chardos have traditionally been an endogamous group, and while they traditionally did not inter-marry or mingle with the low caste Sudirs (Konkani: Shudras), Mahars and Chamars, the statutes and norms of the Roman Catholic church restrained them from discriminating against the latter.[13]

See also

- Christianisation of Goa

- Christianity in Goa

- Christianity in Karnataka

- Cuncolim Revolt

- Caste system among Indian Christians

- Roman Catholicism in Goa

- Roman Catholicism in Mangalore

- Padval

- Forward caste

- Konkani people

- Konkan Marathas

- Roman Catholic Brahmin

Citations

- Silva & Fuchs 1965, p. 4

- Gomes 1987, pp. 77–78

- Risley & Crooke 1915, p. 80

- Pinto 1999, p. 165

- Silva & Fuchs 1965, p. 15

- Robinson 2003, p. 78

- Gune & Goa, Daman and Diu (India). Gazetteer Dept 1979, p. 21

- Prabhu 1999, p. 133

- Pinto 1999, p. 166

- Pinto 1999, p. 180

- Desai 2000, p. 5

- Pereira

- Sinha 2002, p. 74

References

- Desai, Nishtha (2000). "The Denationalisation of Goans: An Insight into the Construction of Cultural Identity" (PDF). Lusotopie: 469–476. Archived from the original (PDF, 36 KB) on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 19 April 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gomes, Olivinho (1987). "Village Goa: a study of Goan social structure and change". S. Chand. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). - Gune, Vithal Trimbak; Goa, Daman and Diu (India). Gazetteer Dept (1979). "Gazetteer of the Union Territory Goa, Daman and Diu: district gazetteer, Volume 1". Gazetteer Dept., Govt. of the Union Territory of Goa, Daman and Diu. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). - Pereira, Benegal, The life and times of Eddie Sadashiva Pereira: An extraordinary Goenkar (1915–1995), Goacom.com, archived from the original on 27 September 2011, retrieved 19 April 2011

- Pinto, Pius Fidelis (1999). "History of Christians in coastal Karnataka, 1500–1763 A.D.". Mangalore: Samanvaya Prakashan. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link). - Prabhu, Alan Machado (1999). Sarasvati's Children: A History of the Mangalorean Christians. I.J.A. Publications. ISBN 978-81-86778-25-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

- Risley, Herbert Hope; Crooke, William (1915). The people of India. Thacker & Co. Retrieved 15 February 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Robinson, Rowena (2003). Christians of India. SAGE. ISBN 978-0-7619-9822-8. Retrieved 19 April 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Silva, Severine; Fuchs, Stephan (1965). "The Marriage Customs of the Christians in South Canara, India" (PDF). Asian Ethnology. 2. 24: 1–52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 March 2012. Retrieved 1 January 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Sinha, Arun (2002). Goa Indica: a critical portrait of postcolonial Goa. Bibliophile South Asia. ISBN 978-81-85002-31-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).

Further reading

- Morenas, Zenaides (2002). "The Mussoll dance of Chandor: the dance of the Christian Kshatriyas". Clarissa Vaz e Morenas Konkani Research Fellowship Endowment Fund. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help)CS1 maint: ref=harv (link).