God in Catholicism

God in Catholicism is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.[1] The Catholic Church believes that there is one true and living God, the Creator and Lord of Heaven and Earth.

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic Church |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

Despite other opinions, God is All-Perfect; this infinite Perfection is viewed, successively, under various aspects, each of which is treated as a separate perfection and characteristic inherent to the Divine Substance, or Essence. A certain group of these, of paramount import, is called the Divine Attributes.

The position of the Catholic Church declared in the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), is again stated in the following pronouncement of the Vatican Council:

- "The Holy, Catholic, Apostolic, Roman Church believes and confesses that there is one, true, living God, Creator and Lord of heaven and earth, omnipotent, eternal, immense, incomprehensible, infinite in intellect and will, and in every perfection; who, although He is one, singular, altogether simple and unchangeable spiritual substance, must be proclaimed distinct in reality and essence from the world; most blessed in Himself and of Himself, and ineffably most high above all things which are or can be conceived outside Himself."

Names

God, being infinite and beyond human comprehension, surpasses any single name.[2] "God revealed himself progressively and under different names to his people, but the revelation that proved to be the fundamental one for both the Old and the New Covenants was the revelation of the divine name to Moses in the theophany of the burning bush..." [3] "I Am Who Am".[4] The word "God" is a translation of the Hebrew word Elohim, which is more of a designation of the deity, than a personal title. "Lord" derives from the Greek word "Kyrios". Jesus frequently used the term Abba, a familiar form of "Father". In 2008, the Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments issued a directive that in liturgical texts the Tetragrammaton is to be translated as "God", and Adonai/Kyrios as "Lord".[5][6]

"Jesus", the name of the second person of the Blessed Trinity, means "God saves" and was revealed by the angel Gabriel (Luke 1:31). It expresses both his identity and his mission.[7] Other names or titles found include "Christ" which means "the anointed one", and "Emmanuel" or "God is with us". Veneration of the Holy Name of Jesus is a particular devotion, promoted by Anselm of Canterbury as early as the 12th century.[8]

The proper name of the third person of the Trinity is the "holy Spirit", from the Hebrew word ruah, meaning breath, air, or wind. He is also called the "Paraclete" as in "advocate", sometimes translated as "consoler".[9]

Historical development

Around 180, in Against Heresies, Irenaeus wrote:

Of his own accord and by his own power he made all things and arranged and perfected them; and his will is the substance of all things. He alone, then, is found to be God; he alone is omnipotent, who made all things; he alone is Father, who founded and formed all things, visible and invisible, sensible and insensate, heavenly and earthly, by the Word of his power. And he has fitted and arranged all things by his wisdom; and while he comprehends all, he can be comprehended by none. He is himself the designer, himself the builder, himself the inventor, himself the maker, himself the Lord of all.[10]

Gregory of Nyssa was one of the first theologians to argue, in opposition to Origen, that God is infinite. His main argument for the infinity of God, which can be found in Against Eunomius, is that God's goodness is limitless, and as God's goodness is essential, God is also limitless.[11]

Thomas Aquinas blended Greek philosophy and Christian doctrine by suggesting that rational thinking and the study of nature, like revelation, were valid ways to understand truths pertaining to God. Faith and reason complement rather than contradict each other, each giving different views of the same truth.

The Deity who, because He is Infinite, cannot be comprehended by finite intelligence. Aquinas felt the best approach, commonly called the via negativa, is to consider what God is not. This led him to propose five statements about the divine qualities:

- God is simple, without composition of parts, such as body and soul, or matter and form.

- God is perfect, lacking nothing. That is, God is distinguished from other beings on account of God's complete actuality.

- God is infinite. That is, God is not finite in the ways that created beings are physically, intellectually, and emotionally limited.

- God is immutable, incapable of change on the levels of God's essence and character.

- God is one, without diversification within God's self. The unity of God is such that God's essence is the same as God's existence. In Thomas's words, "in itself the proposition 'God exists' is necessarily true, for in it subject and predicate are the same."[12]

Knowledge of God

Thomas Aquinas said that starting from movement, becoming, contingency, and the world's order and beauty, one can come to a knowledge of God as the origin and the end of the universe.[13] Aquinas expressed the doctrine that, is now the common teaching of Catholic theologians and philosophers. It may be summarized as follows: The idea of God is derived from our knowledge of finite beings.[14] Accordingly, God reveals himself through nature, so to study nature is to study God.The Church teaches that God can be known with certainty from the created world with human reason.[15]

Created things, by the properties and activities of their natures, manifest, as in a glass, darkly, the powers and perfections of the creator. But these refracted images of Him in finite things cannot furnish grounds for any adequate idea of the Infinite Being.[14] "Since our knowledge of God is limited, our language about him is equally so. We can name God only by taking creatures as our starting point,...Our human words always fall short of the mystery of God."[16]

Throughout the writings of the Fathers the spirituality of the Divine Nature, as well as the inadequacy of human thought to comprehend the greatness, goodness, and infinite perfection of God, is continually emphasized. At the same time, Catholic philosophy and theology set forth the idea of God by means of concepts derived chiefly from the knowledge of our own faculties, and our mental and moral characteristics. We reach our philosophic knowledge of God by inference from the nature of various forms of existence, our own included, that we perceive in the Universe. All created excellence, however, falls infinitely short of the Divine perfections, consequently our idea of God can never truly represent Him as He is, and, because He is infinite while our minds are finite, the resemblance between our thought and its infinite object must always be faint.[17]

Sometimes men are led by a natural tendency to think and speak of God as if He were a magnified creature — more especially a magnified man — and this is known as anthropomorphism. Thus God is said to see or hear, as if He had physical organs, or to be angry or sorry, as if subject to human passions: and this is a perfectly legitimate and more or less unavoidable use of metaphor.[18]

Revelation

"By natural reason man can know God with certainty, on the basis of his works. But there is another order of knowledge, which man cannot possibly arrive at by his own powers: the order of divine Revelation. Through an utterly free decision, God has revealed himself and given himself to man..."[19] By revealing himself God wishes to make man capable of responding to him, and of knowing him and of loving him far beyond their own natural capacity. God communicates himself to man gradually.[20]

According to Dei verbum, the Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation, God reveals himself through his Word;

- in Creation: "God, who through the Word creates all things (see John 1:3) and keeps them in existence, gives men an enduring witness to Himself in created realities (see Rom. 1:19-20)."[21]

- in Sacred Scripture: "Those divinely revealed realities which are contained and presented in Sacred Scripture have been committed to writing under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit."[22]

- through Jesus Christ: "Jesus perfected revelation by fulfilling it through his whole work of making Himself present and manifesting Himself: through His words and deeds, His signs and wonders, but especially through His death and glorious resurrection from the dead and final sending of the Spirit of truth."[23]

Nature

Reason teaches that God is one simple and infinitely perfect spiritual substance or nature. Sacred Scripture and the Church teach the same. The creeds usually begin with a profession of faith in the one true God, Who is the Creator and Lord of heaven and earth.[24] As stated by the First Vatican Council: "The Catholic Church believes that there is one true and living God, the Creator and Lord of heaven and earth, Almighty, Eternal, Immense, Incomprehensible, Infinite in intellect and will and in all perfection; who, being One, Individual, altogether simple and unchangeable Substance, must be asserted to be really and essentially distinct from the world, most happy (blessed) in Himself, and ineffably exalted above everything that exists or can be conceived."[4]

As a personal being, God is intelligent, free, and distinct from the created universe. According to Tatian, "“Our God has no introduction in time. He alone is without beginning, and is himself the beginning of all things. God is a spirit, not attending upon matter, but the maker of material spirits and of the appearances which are in matter. He is invisible, being himself the Father of both sensible and invisible things”God is Creator of all that exists.[25] Francis J. Beckwith explains, "God keeps the universe in existence at every moment, since a universe, even an everlasting and infinitely large one, consisting entirely of contingent beings in causal relationships with each other, could no more exist without some sustaining First Cause than could an alleged perpetual motion machine exist without an Unmoved Mover keeping its motion perpetual.[26]

John Henry Newman in the Grammar of Assent said,

"Conscience always involves the recognition of a living object towards which it is directed. Inanimate things cannot stir our affections; these are correlative with persons. If, as is the case, we feel responsibility, are ashamed, are frightened, at transgressing the voice of conscience, this implies that there is One to whom we are responsible, before whom we are ashamed, whose claims upon us we fear... we certainly have within us the image of some Person to whom our love and veneration look,... such as require for their exciting cause an Intelligent Being.[4]

It is in God's nature to love, to forgive, to heal, protect and save. Even when human beings do what is wrong or selfish or evil, God's nature does not change.[27]

Presence

The term the "Presence of God" refers to the belief that God is present by His Essence everywhere and in all things by reason of His Immensity. Psalm 139:7-8 reads: "Where can I go from your Spirit? Where can I flee from your presence? If I go up to the heavens, you are there; if I make my bed in the depths, you are there.'

It also refers to the belief that God is in a special manner really and substantially present in the souls of the just.[28] In devotion, to put oneself in the presence of God, or to live in the presence of God, as spiritual writers express it, means to become actually conscious of God as present, or at least so to live as though thus actually conscious.[28]

Another way to be mindful of His Presence is by the exercise of reason directed by faith. One sees God in the earth, the sea, the air and in all things; in heaven where He manifests His Glory, in hell where He carries out the law of His Justice.[28] A writer particularly associated with this devotion is Brother Lawrence, the author of The Practice of the Presence of God.

Way of eminence

The concept of a perfection derived from created things and freed of all defects, is, in its application to God, expanded without limit. God not only possesses every excellence discoverable in creation, but He also possesses it infinitely. To emphasize the transcendence of the Divine perfection, in some cases an abstract noun is substituted for the corresponding adjective; as, God is Intelligence; or, again, some word of intensive, or exclusive, force is joined to the attribute; as, God alone is good, God is goodness itself, God is all-powerful, or supremely powerful.

As God is transcendent of all temporal limitations, so also is He transcendent in relation to space. God is both immanent and transcendent; necessarily present everywhere in space as the immanent cause and sustainer of creatures, and on the other hand, He transcends the limitations of actual and possible space, and cannot be circumscribed or measured or divided by any spatial relations.[24]

Attributes

God is eternal in that in essence, life, and action he is altogether beyond temporal limits and relations. He has neither beginning, nor end, nor duration by way of sequence or succession of moments. There is no past or future for God — but only an eternal present. This is expressed by Christ when he says in John 8:58: "Before Abraham was, I am."[24] The eternity of God is a corollary from His self-existence and infinity. Time being a measure of finite existence, the infinite must transcend it. God, it is true, coexists with time, as He coexists with creatures, but He does not exist in time, so as to be subject to temporal relations: His self-existence is timeless.

The Deity, because he is Infinite, cannot be comprehended by finite intelligence. The Divine Perfection, one and invisible, is, in its infinity, the transcendental analogue of all actual and possible finite perfections. By means of an accumulation of analogous predicates methodically co-ordinated, it is possible to form an approximate conception of the Deity. Other attributes are simplicity, perfection, infinity, immutability, unity, truth, goodness, beauty, omnipresence, intellect and will.[29] According to Aquinas, the Simplicity of God means that God has no parts, that He is not composed in any way. In God, essence and existence are the same thing. His wisdom, justice, mercy, and all His attributes are not really distinct from each other nor from His essence.[30]

Only God's omnipotence is named in the Creed: his might is universal, for God who created everything also rules everything and can do everything.[31]

God is a spirit, an immaterial substance having intellect and will, although often described in anthropomorphic imagery. When the scriptures attribute to God human emotions such as of hatred, joy, pity, repentance, etc., they do so figuratively.[30]

Infinite

God is infinite in that he is unlimited in every kind of perfection or that every conceivable perfection belongs to him in the highest conceivable way. Given an infinite cause and finite effects, whatever pure perfection is discovered in the effects must first exist in the cause (via affirmationis) and at the same time that whatever imperfection is discovered in the effects must be excluded from the cause (via negationis vel exclusionis). These two principles do not contradict, but only balance and correct one another. What is contemplated directly is the portrait of God painted on the canvas of the universe and exhibiting in a finite degree various perfections, which, without losing their proper meaning for us, are seen to be capable of being realized in an infinite degree; and reason compels the inference that they must be and are so realized in Him who is their ultimate cause.[24]

Unity

Because a self-existent being as such is necessarily infinite, and there cannot be several infinities.[24]

Simplicity

Simplicity means that God is a simple being or substance excluding every kind of composition, physical or metaphysical. An infinite being cannot be substantially composite, for this would mean that infinity is made up of the union or addition of finite parts.[24]

Personal

To say that God is a personal being means that he is intelligent and free and distinct from the created universe.[24]

Trinity

The Trinity is the term employed to signify the central doctrine of the Christian religion — the truth that in the unity of the Godhead there are Three Persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, these Three Persons being truly distinct one from another. Thus, in the words of the Athanasian Creed: "the Father is God, the Son is God, and the Holy Spirit is God, and yet there are not three Gods but one God." In this Trinity of Persons the Son is begotten of the Father by an eternal generation, and the Holy Spirit proceeds by an eternal procession from the Father and the Son. Yet, notwithstanding this difference as to origin, the Persons are co-eternal and co-equal: all alike are uncreated and omnipotent.[32]

In Matthew 28:19 Jesus says, "Go, therefore,* and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the holy Spirit..." In John 1: 1-18, the evangelist identifies Jesus with the Word, the only-begotten of the Father, Who from all eternity exists with God, and Who is God.[32]

St. Basil the Great tells of an ancient custom among Christians when they lit the evening lamp to give thanks to God with the prayer: "We praise the Father, and the Son, and the Holy Spirit of God".[32] "The Christian begins his day, his prayers, and his activities with the Sign of the Cross: "in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Amen." The baptized person dedicates the day to the glory of God and calls on the Savior's grace which lets him act in the Spirit as a child of the Father."[33]

Jesus

The divinity of Christ is an essential teaching of the Catholic faith. Jesus has two distinct natures in one person; a Divine nature as God, and a human nature as man.[34] "The Gospels report that at two solemn moments, the Baptism and the Transfiguration of Christ, the voice of the Father designates Jesus his "beloved Son". Jesus calls himself the "only Son of God", and by this title affirms his eternal pre-existence."[35]

By the expression "He descended into hell", the Apostles' Creed confesses that Jesus, like all men, experienced death and through his death conquered death and the devil "who has the power of death".[36] The Nicean Creed states,

•I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; through him all things were made. For us men and for our salvation he came down from heaven, and by the Holy Spirit was incarnate of the Virgin Mary, and became man. For our sake he was crucified under Pontius Pilate, he suffered death and was buried, and rose again on the third day in accordance with the Scriptures. He ascended into heaven and is seated at the right hand of the Father. He will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead and his kingdom will have no end.[37]

Kingdom

In the New Testament, the phrase "Kingdom of God" or "Kingdom of Heaven" has various shades of meaning. It means, then, the ruling of God in the hearts of the faithful; those principles which distinguish believers from the kingdom of the world and the devil; the benign sway of grace; the Church as that Divine institution whereby one may make sure of attaining the spirit of Christ and so win that ultimate kingdom of God Where He reigns without end in "the holy city, the New Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God".[38]

In the Gospel of Matthew, Jesus explains that detaching oneself from the things of this world (Mt 19:24), doing the will of the Father (Mt 21:31), and bearing good fruit (Mt 21:43) are necessary to enter the Kingdom of God.[39] It refers to the effective rule of God over his people."In the expectation found in Jewish apocalyptic, the kingdom was to be ushered in by a judgment in which sinners would be condemned and perish,... This was modified in Christian understanding where the kingdom was seen as being established in stages, culminating with the Parousia of Jesus."[40] At the beginning of Jesus' ministry in Galilee, he proclaims "“This is the time of fulfillment. The kingdom of God is at hand. Repent, and believe in the gospel.”[41] The Proclamation of the Kingdom of God is the third Luminous Mystery.[42]

Jesus not only proclaims the coming of the kingdom by his word but in his actions of healing and forgiveness makes the kingdom actually present. "The kingdom is understood by most Roman Catholic theologians to be both present and future; it is both "now" and "not yet"."[43] "...the promised restoration which we are awaiting has already begun in Christ, is carried forward in the mission of the Holy Spirit and through Him continues in the Church.'[44]

Economy

The Fathers of the Church distinguish between theology (theologia) and economy (oikonomia). "Theology" refers to the mystery of God's inmost life within the Blessed Trinity and "economy" to all the works by which God reveals himself and communicates his life. Through the oikonomia the theologia is revealed to us; but conversely, the theologia illuminates the whole oikonomia. God's works reveal who he is in himself; the mystery of his inmost being enlightens our understanding of all his works. So it is, analogously, among human persons. A person discloses himself in his actions, and the better we know a person, the better we understand his actions.[45]

Depictions

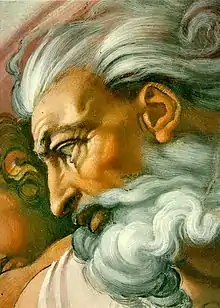

The Catholic Church has always defended the use of sacred images in churches, shrines, and homes, encouraging their veneration but distinguishing between veneration and worship. In Western art, God the Father is conventionally shown as a patriarch, with benign, yet powerful countenance and with long white hair and a beard, a depiction largely derived from the description of the Ancient of Days in the Old Testament.[46]

The Holy Spirit is almost always depicted as a dove.[47]

See also

Notes

- Catechism of the Catholic Church 203 and 205

- Kerper, Michael. "What is God's Name?", Parable Magazine", January/February 2011

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, §204

- Conway C.S.P., Bertrand L., "The Existence and Nature of God", 1929

- Congregation for Divine Worship and the Discipline of the Sacraments, "Letter to the Bishops' Conferences on the 'Name of God'", June 29, 2008

- "The Name of God in the Liturgy", USCCB

- CCC §430

- Reading in the Wilderness: Private Devotion and Public Performance in Late Medieval England by Jessica Brantley 2007 ISBN 0-226-07132-4 pages 178-193

- "The Name, Titles, and Symbols of the Holy Spirit", The Roman Catholic Diocese of Dallas, May 15, 2013

- Irenaeus. Against Heresies, 2:30:9

- The Brill Dictionary of Gregory of Nyssa. (Lucas Francisco Mateo-Seco and Giulio Maspero, eds.) 2010. Leiden: Brill, p. 424

- Kreeft, Peter (1990). Summa of the Summa. Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-300-X

- Toner, Patrick. "The Existence of God." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 16 April 2018

- Fox, James. "Divine Attributes." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 16 April 2018

- Catechism of the Catholic Church, §36

- CCC §§40, 42.

- Fox, James. "Anthropomorphism, Anthropomorphites." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 1. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 16 April 2018

- Toner, Patrick. "The Nature and Attributes of God." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 16 April 2018

- CCC §50.

- CCC §§52, 53.

- Pope Paul VI, Dei Verbum, §3, November 18, 1965

- Dei Verbum, §11.

- Dei Verbum, §4.

- Toner, Patrick. "The Nature and Attributes of God." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 6. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1909. 13 July 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Tatian, "Address to the Greeks

- Beckwith, Francis J., "Who is God?", The Catholic Thing, June 22, 2016

- Sánchez, Patricia Datchuck. "The Nature of God", National Catholic Reporter, March 28, 2014

- Devine, Arthur. "Presence of God." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1911. 23 September 2016

- Fox, James. "Divine Attributes." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 2. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1907. 13 July 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Coppens S.J., Charles. "God's Quiescent Attributes", The Catholic Religion

- CCC §268

- Joyce, George. "The Blessed Trinity." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 15. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1912. 13 July 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - CCC §2157

- Gaskin, Gerard. "Jesus Christ, the Person", The Catholic (Universal) Catechism

- CCC §444

- CCC §632

- "What do Catholics Believe?", Roman Catholic Diocese of Lansing

- Pope, Hugh. "Kingdom of God." The Catholic Encyclopedia Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 14 July 2019

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - Mirus, Jeff. "Entering the Kingdom of God: What Does This Mean?", Catholic Culture, May 22, 2014

- NAB, note to Matthew 3:2

- CCC §541

- "Third Luminous Mystery: Proclamation of the Kingdom of God", USCCB

- Dollard, Jerome R. “Eschatology: A Roman Catholic Perspective.” Review & Expositor, vol. 79, no. 2, May 1982, p. 367 doi:10.1177/003463738207900217

- Pope Paul VI. "Lumen gentium, Dogmatic Constitution on the Church", §48, November 21, 1964

- CCC §236.

- Bigham, Stephen. Image of God the Father in Orthodox Theology and Iconography, 1995. ISBN 1-879038-15-3

- Bourlier, Cyriil. "Introduction to Medieval Iconography", Artnet News, October 28, 2013

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Nature and Attributes of God". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "The Nature and Attributes of God". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Divine Attributes". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Divine Attributes". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.