Konkani language

Konkani[note 4] (Kōṅkaṇī) is an Indo-Aryan language spoken by the Konkani people, primarily along the western coastal region (Konkan) of India. It is one of the 22 Scheduled languages mentioned in the 8th schedule of the Indian Constitution[9] and the official language of the Indian state of Goa. The first Konkani inscription is dated 1187 A.D.[10] It is a minority language in Karnataka, Maharashtra, Kerala,[11] Gujarat and Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu.

| Konkani | |

|---|---|

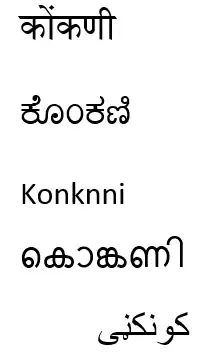

| कोंकणी / ಕೊಂಕಣಿ/ Konknni/ കോങ്കണീ/ کونکڼی | |

"Konkani" in Devanagari script | |

| Pronunciation | [kõkɳi] (in the language itself), [kõkɵɳi] (anglicised) |

| Native to | India |

| Region | Konkan (includes Goa and the coastal areas of Karnataka, Mangalore, Maharashtra and some parts of Kerala, Gujarat (Dang district) and Dadra and Nagar Haveli and Daman and Diu)[1][2] |

| Ethnicity | Konkani people |

Native speakers | 2.3 million (2011 census)[3] |

| Dialects |

|

| Past: Brahmi Nāgarī Goykanadi Modi script Present: Devanagari (official)[note 1] Roman[note 2] Kannada[note 3] Malayalam[5] | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

| Regulated by | Karnataka Konkani Sahitya Academy and the Government of Goa[7] |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-2 | kok |

| ISO 639-3 | kok – inclusive codeIndividual codes: gom – Goan Konkaniknn – Maharashtrian Konkani |

| Glottolog | goan1235 Goan Konkanikonk1267 Konkani |

Distribution of native Konkani speakers in India | |

Konkani is a member of the Southern Indo-Aryan language group. It retains elements of Vedic structures and shows similarities with both Western and Eastern Indo-Aryan languages.[12]

There are many fractured Konkani dialects spoken along and beyond the Konkan, from Damaon in the north to Cochin in the South, most of which are only partially mutually intelligible with one another due to a lack of linguistic contact and exchanges with the standard and principle forms of Konkani. Dialects such as Malvani, Chitpavani, East Indian Koli and Aagri in coastal Maharashtra, are also threatened by language assimilation into the linguistic majority of non-Konkani States of India.[13][14]

Classification

Konkani belongs to the Indo-Aryan language branch. It is a part of the Marathi-Konkani group of the Southern Indo-Aryan languages.[15] It is inflexive, and less distant from Sanskrit as compared to other modern Indo-Aryan languages. Linguists describe Konkani as a fusion of variety of Prakrits. This could be attributed to the confluence of immigrants that the Konkan coast has witnessed over the years.[16]

Names

It is quite possible that Old Konkani was just referred to as Prakrit by its speakers.[17] Reference to the name Konkani is not found in literature prior to the 13th century. The first reference of the name Konkani is in "Abhanga 263" of the 13th century Marathi saint poet, Namadeva (1270–1350).[18] Konkani has been known by a variety of names: Canarim, Concanim, Gomantaki, Bramana, and Goani. Learned Marathi speakers tend to call it Gomantaki.[19]

Konkani was commonly referred to as Lingua Canarim by the Portuguese[20] and Lingua Brahmana by Catholic missionaries.[20] The Portuguese later started referring to Konkani as Lingua Concanim.[20] The name Canarim or Lingua Canarim, which is how the 16th century European Jesuit, Thomas Stephens refers to it in the title of his famous work Arte da lingoa Canarim has always been intriguing. It is possible that the term is derived from the Persian word for coast, kinara; if so, it would mean "the language of the coast". The problem is that this term overlaps with Kanarese or Kannada.[21] All the European authors, however, recognised two forms of the language in Goa: the plebeian, called Canarim, and the more regular (used by the educated classes), called Lingua Canarim Brámana or simply Brámana de Goa. The latter was the preferred choice of the Europeans, and also of other castes, for writing, sermons, and religious purposes.[22]

There are different views as to the origin of the word Konkan and hence Konkani

- The word Konkan comes from the Kukkana (Kokna) tribe, who were the original inhabitants of the land where Konkani originated.[23]

- According to some texts of Hindu mythology, Parashurama shot his arrow into the sea and commanded the Sea God to recede up to the point where his arrow landed. The new piece of land thus recovered came to be known as Konkan meaning piece of earth or corner of earth, kōṇa (corner) + kaṇa (piece). This legend is mentioned in Sahyadrikhanda of the Skanda Purana.

History

Proposed substrate influences

The substratum of the Konkani language lies in the speech of Austroasiatic tribes called Kurukh, Oraon, and Kukni, whose modern representatives are languages like Kurukh and its dialects including Kurux, Kunrukh, Kunna, and Malto.[24] According to the Indian Anthropological Society, these Australoid tribes speaking Austro-Asiatic or Munda languages who once inhabited Konkan, migrated to Northern India (Chota Nagpur Plateau, Mirzapur) and are not found in Konkan any more.[25][26] Olivinho Gomes in his essay "Medieval Konkani Literature" also mentions the Mundari substratum.[27] Goan Indologist Anant Shenvi Dhume identified many Austro-Asiatic Munda words in Konkani, like mund, mundkar, dhumak, goem-bab.[28] This substratum is very prominent in Konkani.[29]

The grammatical impact of the Dravidian languages on the structure and syntax of Indo-Aryan languages is difficult to fathom. Some linguists explain this anomaly by arguing that Middle Indo-Aryan and New Indo-Aryan were built on a Dravidian substratum.[30] Some examples of Konkani words of Dravidian origin are: naall (coconut), madval (washerman), choru (cooked rice) and mulo (radish).[31] Linguists also suggest that the substratum of Marathi and Konkani is more closely related to Dravidian Kannada.[32][33]

Pre-history and early development

Migrations of Indo-Aryan vernacular speakers have occurred throughout the history of the Indian west coast. Around 2400 BC the first wave of Indo-Aryans dialect speakers might have occurred, with the second wave appearing around 1000–700 BC.[28] Many spoke old Indo-Aryan vernacular languages, which may be loosely related to Vedic Sanskrit; others still spoke Dravidian and Desi dialects. Thus the ancient Konkani Prakrit was born as a confluence of the Indo-Aryan dialects while accepting many words from Dravidian speech. Some linguists assume Shauraseni to be its progenitor whereas some call it Paisaci. The influence of Paisachi over Konkani can be proved in the findings of Dr. Taraporewala, who in his book Elements of Science of Languages (Calcutta University) ascertained that Konkani showed many Dardic features that are found in present-day Kashmiri.[16] Thus, the archaic form of old Konkani is referred to as Paishachi by some linguists.[23] This progenitor of Konkani (or Paishachi Apabhramsha) has preserved an older form of phonetic and grammatic development, showing a great variety of verbal forms found in Sanskrit and a large number of grammatical forms that are not found in Marathi. (Examples of this are found in many works like Dnyaneshwari, and Leela Charitra.[34]) Konkani thus developed with overall Sanskrit complexity and grammatical structure, which eventually developed into a lexical fund of its own.[34] The second wave of Indo-Aryans is believed to have been accompanied by Dravidians from the Deccan plateau.[28] Paishachi is also considered to be an Aryan language spoken by Dravidians.[35]

Goa and Konkan was ruled by the Konkan Mauryas and the Bhojas; as a result numerous migrations occurred from North, East and Western India. Immigrants spoke various vernaculars, which led to a mixture of features of Eastern and Western Prakrits. It was substantially influenced later by Magadhi Prakrit.[36] The overtones of Pali[34] (the liturgical language of the Buddhists) also played a very important role in the development of Konkani Apabhramsha grammar and vocabulary.[37] A major number of linguistic innovations in Konkani are shared with Eastern Indo-Aryan languages like Bengali and Oriya, which have their roots in Magadhi.[38]

Maharashtri Prakrit is the ancestor of Marathi and Konkani,[39] it was the official language of the Satavahana Empire that ruled Goa and Konkan in the early centuries of the Common Era. Under the patronage of the Satavahana Empire, Maharashtri became the most widespread Prakrit of its time. Studying early Maharashtri compilations, many linguists have called Konkani "the first-born daughter of Maharashtri".[40] This old language that was prevalent contemporary to old Marathi is found to be distinct from its counterpart.[40]

The Sauraseni impact on Konkani is not as prominent as that of Maharashtri. Very few Konkani words are found to follow the Sauraseni pattern. Konkani forms are rather more akin to Pali than the corresponding Sauraseni forms.[41] The major Sauraseni influence on Konkani is the ao sound found at the end of many nouns in Sauraseni, which becomes o or u in Konkani.[42] Examples include: dando, suno, raakhano, dukh, rukhu, manisu (from Prakrit), dandao, sunnao, rakkhakao, dukkhao, vukkhao, vrukkhao, and mannisso. Another example could be the sound of ण at the beginning of words; it is still retained in many Konkani words of archaic Shauraseni origin, such as णव (nine). Archaic Konkani born out of Shauraseni vernacular Prakrit at the earlier stage of the evolution (and later Maharashtri Prakrit), was commonly spoken until 875 AD, and at its later phase ultimately developed into Apabhramsha, which could be called a predecessor of old Konkani.[37]

Although most of the stone inscriptions and copper plates found in Goa (and other parts of Konkan) from the 2nd century BC to the 10th century AD are in Prakrit-influenced Sanskrit (mostly written in early Brahmi and archaic Dravidian Brahmi), most of the places, grants, agricultural-related terms, and names of some people are in Konkani. This suggests that Konkani was spoken in Goa and Konkan.[43]

Though it belongs to the Indo-Aryan group, Konkani was influenced by a language of the Dravidian family. A branch of the Kadambas, who ruled Goa for a long period, had their roots in Karnataka. Konkani was never used for official purposes.[44] Another reason Kannada influenced Konkani was the proximity of original Konkani-speaking territories to Karnataka.[45] Old Konkani documents show considerable Kannada influence on grammar as well as vocabulary. Like southern Dravidian languages, Konkani has prothetic glides y- and w-.[46] The Kannada influence is more evident in Konkani syntax. The question markers in yes/no questions and the negative marker are sentence final.[46] Copula deletion in Konkani is remarkably similar to Kannada.[46] Phrasal verbs are not so commonly used in Indo-Aryan languages; however, Konkani spoken in Dravidian regions has borrowed numerous phrasal verb patterns.[47]

The Kols, Kharwas, Yadavas, and Lothal migrants all settled in Goa during the pre-historic period and later. Chavada, a tribe of warriors (now known as Chaddi or Chaddo), migrated to Goa from Saurashtra, during the 7th and 8th century AD, after their kingdom was destroyed by the Arabs in 740.[48] Royal matrimonial relationships between the two states, as well as trade relationships, had a major impact on Goan society. Many of these groups spoke different Nagar Apabhramsha dialects, which could be seen as precursors of modern Gujarati.

- Konkani and Gujarati have many words in common, not found in Marathi.[49]

- The Konkani O (as opposed to the Marathi A, which is of different Prakrit origin), is similar to that in Gujarati.[49]

- The case terminations in Konkani, lo, li, and le, and the Gujarati no, ni, and ne have the same Prakrit roots.[49]

- In both languages the present indicatives have no gender, unlike Marathi.[49]

Early Konkani

An inscription at the foot of the colossal Jain monolith Bahubali (The word gomateshvara apparently comes from Konkani gomaṭo which means "beautiful" or "handsome" and īśvara "lord".[50]) at Shravanabelagola of 981 CE reads, in a variant of Nāgarī:[51]

"śrīcāvuṇḍarājē̃ kara viyālē̃, śrīgaṅgārājē̃ suttālē̃ kara viyālē̃" (Chavundaraya got it done, Gangaraya got the surroundings done).[note 5][note 6]

The language of these lines is Konkani according to S.B. Kulkarni (former head of Department of Marathi, Nagpur University) and Jose Pereira (former professor, Fordham University, USA).

Another inscription in Nāgarī, of Shilahara King Aparaditya II of the year 1187 AD in Parel reportedly contains Konkani words, but this has not been reliably verified.[52]

Many stone and copper-plate inscriptions found in Goa and Konkan are written in Konkani. The grammar and the base of such texts is in Konkani, whereas very few verbs are in Marathi.[53] Copper plates found in Ponda dating back to the early 13th century, and from Quepem in the early 14th century, have been written in Goykanadi.[27] One such stone inscription or shilalekh (written Nāgarī) is found at the Nageshi temple in Goa (dating back to the year 1463 AD). It mentions that the (then) ruler of Goa, Devaraja Gominam, had gifted land to the Nagueshi Maharudra temple when Nanjanna Gosavi was the religious head or Pratihasta of the state. It mentions words like, kullgga, kulaagra, naralel, tambavem, and tilel.[54]

A piece of hymn dedicated to Lord Narayana attributed to the 12th century AD says:

"jaṇẽ rasataḷavāntũ matsyarūpē̃ vēda āṇiyēlē̃. manuśivāka vāṇiyēlē̃. to saṁsārasāgara tāraṇu. mōhō to rākho nārāyāṇu". (The one who brought the Vedas up from the ocean in the form of a fish, from the bottoms of the water and offered it to Manu, he is the one Saviour of the world, that is Narayana my God.).

A hymn from the later 16th century goes

vaikuṇṭhācē̃ jhāḍa tu gē phaḷa amṛtācē̃, jīvita rākhilē̃ tuvē̃ manasakuḷācē̃.[55]

Early Konkani was marked by the use of pronouns like dzo, jī, and jẽ. These are replaced in contemporary Konkani by koṇa. The conjunctions yedō and tedō ("when" and "then") which were used in early Konkani are no longer in use.[56] The use of -viyalẽ has been replaced by -aylẽ. The pronoun moho, which is similar to the Brijbhasha word mōhē has been replaced by mākā.

Medieval Konkani

This era was marked by the invasion of Goa and subsequent exodus to Marhatta territory, Canara (today's coastal Karnataka), and Cochin.

- Exodus (between 1312–1327) when General Malik Kafur of the Delhi Sultans, Alauddin Khalji, and Muhammed bin Tughlaq destroyed Govepuri and the Kadambas

- Exodus subsequent to 1470 when the Bahamani kingdom captured Goa, and subsequent capture in 1492 by Sultan Yusuf Adil Shah of Bijapur

- Exodus due to the Christianization of Goa by Portuguese subsequent to 1500

- Hindu, Muslim, and Neo-Catholic Christian exodus during the Goa Inquisition, which was established in 1560 and abolished in 1812.

These events caused the Konkani language to evolve into multiple dialects. The exodus to coastal Karnataka and Kerala required Konkani speakers in these regions to learn the local languages. This caused penetration of local words into the dialects of Konkani spoken by these speakers. Examples include dār (door) giving way to the word bāgil. Also, the phoneme "a" in the Salcette dialect was replaced by the phoneme "o".

Other Konkani communities came into being with their own dialects of Konkani. The Konkani Muslim communities of Ratnagiri and Bhatkal came about due to a mixture of intermarriages of Arab seafarers and locals as well as conversions of Hindus to Islam.[57] Another migrant community that picked up Konkani are the Siddis, who are descended from Bantu peoples from South East Africa that were brought to the Indian subcontinent as slaves by Portuguese merchants.[58]

Contemporary Konkani

Contemporary Konkani is written in Devanagari, Kannada, Malayalam, Persian, and Roman scripts. It is written by speakers in their native dialects. However, the Goan Antruz dialect in the Devanagari script has been promulgated as Standard Konkani.

Konkani revival

Konkani was in a sorry state, due to the use of Portuguese as the official and social language among the Christians, the predominance of Marathi over Konkani among Hindus, and the Konkani Christian-Hindu divide. Seeing this, Vaman Raghunath Varde Valaulikar set about on a mission to unite all Konkanis, Hindus as well as Christians, regardless of caste or religion. He saw this movement not just as a nationalistic movement against Portuguese rule, but also against the pre-eminence of Marathi over Konkani. Almost single-handedly he crusaded, writing a number of works in Konkani. He is regarded as the pioneer of modern Konkani literature and affectionately remembered as Shenoi Goembab.[59] His death anniversary, 9 April, is celebrated as World Konkani Day (Vishwa Konkani Dis).[60]

Madhav Manjunath Shanbhag, an advocate by profession from Karwar, who with a few like-minded companions travelled throughout all the Konkani speaking areas, sought to unite the fragmented Konkani community under the banner of "one language, one script, one literature". He succeeded in organising the first All India Konkani Parishad in Karwar in 1939.[61] Successive Adhiveshans of All India Konkani Parishad were held at various places in subsequent years. 27 annual Adhiveshans of All India Konkani Parishad have been held so far.

Pandu Putti Kolambkar an eminent social worker of Kodibag, Karwar strove for the upliftment of Konkani in Karwar (North Kanara) and Konkan.

Post-independence period

Following India's independence and its subsequent annexation of Goa in 1961, Goa was absorbed into the Indian Union as a Union Territory, directly under central administration.

However, with the reorganisation of states along linguistic lines, and growing calls from Maharashtra, as well as Marathis in Goa for the merger of Goa into Maharashtra, an intense debate was started in Goa. The main issues discussed were the status of Konkani as an independent language and Goa's future as a part of Maharashtra or as an independent state. The Goa Opinion Poll, a plebiscite, retained Goa as an independent state in 1967.[59] However, English, Hindi, and Marathi continued to be the preferred languages for official communication, while Konkani was sidelined.[6]

Recognition as an independent language

With the continued insistence of some Marathis that Konkani was a dialect of Marathi and not an independent language, the matter was finally placed before the Sahitya Akademi. Suniti Kumar Chatterji, the president of the Akademi appointed a committee of linguistic experts to settle the dispute. On 26 February 1975, the committee came to the conclusion that Konkani was indeed an independent and literary language, classified as an Indo-European language, which in its present state was heavily influenced by the Portuguese language.

Official language status

All this did not change anything in Goa. Finally fed up with the delay, Konkani activists launched an agitation in 1986, demanding official status for Konkani. The agitation turned violent in various places, resulting in the death of six agitators from the Catholic community: Floriano Vaz from Gogal Margao, Aldrin Fernandes, Mathew Faria, C. J. Dias, John Fernandes, and Joaquim Pereira, all from Agaçaim. Finally, on 4 February 1987, the Goa Legislative Assembly passed the Official Language Bill, making Konkani the official language of Goa.[6]

Konkani was included in the Eighth Schedule to the Constitution of India as per the Seventy-First Amendment on 20 August 1992, adding it to the list of national languages.

Geographical distribution

The Konkani language originated and is spoken widely in the western coastal region of India known as Konkan. The native lands historically inhabited by Konkani people include the Konkan division of Maharashtra, the state of Goa and the territory of Damaon, the Uttara Kannada (North Canara), Udupi& Dakshina Kannada (South Canara) districts of Karnataka, along with many districts in Kerala such as Kasaragod (formerly part of South Canara), Kochi (Cochin), Alappuzha (Allepey), Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum), and Kottayam. Each the region's and areas have a developed distinct dialects, pronunciation and prose styles, vocabulary, tone and sometimes, significant differences in grammar.[62]

According to the 2001 estimates of the Census Department of India, there were 2,489,016 Konkani speakers in India.[63] The Census Department of India, 2011 figures put the number of Konkani speakers in India as 2,256,502 making up 0.19% of India's population. Out of these, 788,294 were in Karnataka, 964,305 in Goa,[64] 399,255 in Maharashtra, and 69,449 in Kerala. It ranks 19th on the List of Scheduled Languages by strength. The number of Konkani speakers in India fell by 9.34% in the decade 2001-2011. It is the only scheduled language apart from Urdu to have a negative growth rate in the decade. A very large number of Konkanis live outside India, either as expatriates (NRIs) with work visas or as naturalised citizens and permanent residents of other host countries (immigrants). Determining their numbers is difficult since Konkani is a minority language that is very often not recognised by censuses and surveys of various government agencies and NGOs catering to Indians abroad.

During the days of Portuguese Goa and British rule in Pre-Partition India many Goans and non-Goan Konkani people went to foreign countries as economic migrants to the Portuguese and British Empires, and to the Pakistan of Pre-Partition India. The migratory trend has continued well into the post-colonial era and a significant number of Konkani people are found in Kenya, Uganda, Pakistan, the Persian Gulf countries, Portugal and the European Union, and the British Isles and the rest of the Anglosphere. Many families still continue to speak different Konkani dialects that their ancestors spoke, which are now highly influenced by the languages of the dominant majority.

Current status

The Konkani language has been in danger of dying out over the years for many of the following reasons:

- The fragmentation of Konkani into various, sometimes mutually unintelligible, dialects.

- The Portuguese influence in Goa, especially on Catholics.

- The strong degree of bilingualism of Konkani Hindus in Goa and coastal Maharashtra with Marathi.

- Progressive inroads made by Urdu into the Muslim communities.

- Mutual animosity among various religious and caste groups; including a secondary status of Konkani culture to religion.

- The migration of Konkanis to various parts of India and around the world.

- The lack of opportunities to study Konkani in schools and colleges. Even until recently there were few Konkani schools in Goa. Populations outside the native Konkani areas have absolutely no access to Konkani education, even informally.

- The preference among Konkani parents to speak to their children in Potaachi Bhas (language of the stomach) over Maaim Bhas (mother tongue). They sometimes speak primarily in English to help their children gain a grip on English in schools.[5]

Efforts have been made to stop this downward trend of usage of Konkani, starting with Shenoi Goembab's efforts to revive Konkani. There has been a renewed interest in Konkani literature. The recognition granted by Sahitya Akademi to Konkani and the institution of an annual award for Konkani literature has helped.

Some organisations, such as the Konkan Daiz Yatra, organised by Konkani Bhasha Mandal, and the newer Vishwa Konkani Parishad have laid great stress on uniting all factions of Konkanis.

Opposition to Konkani language

Karnataka MLC Mr. Ivan D'Souza attempted to speak in Konkani at the Karnataka State Legislative Council, but was however urged not to by the Chairman D H Shankaramurthy as most of the audience did not know Konkani. Even though Mr. D'Souza pleaded that Konkani was amongst the 22 official languages recognised by the Indian Constitution, he was not given permission to continue in Konkani.[65][66][67][68]

Even though there are substantial Konkani Catholics in Bengaluru, efforts to celebrate mass in Konkani have met with opposition by Kannada activists. Konkani mass has been held in the Sabbhavana and Saccidananda chapels of the Carmelite and Capuchin Fathers respectively, in Yeswanthpur and Rajajinagar. These services are under constant threat from Kannada activists who do not want mass to be celebrated in any other language other than Kannada, even though Kannada Catholics constitute only 20% of the Catholic population in the Archdiocese. Konkani speakers of Mysore and Shimoga districts have been demanding Konkani-language Mass celebrations for a long time.[69][70][71][72][73] Konkani is, however, still the official language of the Mangalore Archdiocese.[74]

Multilingualism

According to the Census Department of India, Konkani speakers show a very high degree of multilingualism. In the 1991 census, as compared to the national average of 19.44% for bilingualism and 7.26% for trilingualism, Konkani speakers scored 74.20% and 44.68% respectively. This makes Konkanis the most multilingual community of India.

This has been due to the fact that in most areas where Konkanis have settled, they seldom form a majority of the population and have to interact with others in the local tongue. Another reason for bilingualism has been the lack of schools teaching Konkani as a primary or secondary language.

While bilingualism is not by itself a bad thing, it has been misinterpreted as a sign that Konkani is not a developed language. The bilingualism of Konkanis with Marathi in Goa and Maharashtra has been a source of great discontent because it has led to the belief that Konkani is a dialect of Marathi[5][75] and hence has no bearing on the future of Goa.

Konkani–Marathi dispute

José Pereira, in his 1971 work Konkani – A Language: A History of the Konkani Marathi Controversy, pointed to an essay on Indian languages written by John Leyden in 1807, wherein Konkani is called a “dialect of Maharashtra” as an origin of the language controversy.[5]

Another linguist to whom this theory is attributed is Grierson. Grierson's work on the languages of India, the Linguistic Survey of India, was regarded as an important reference by other linguists. In his book, Grierson had distinguished between the Konkani spoken in coastal Maharashtra (then, part of Bombay) and the Konkani spoken in Goa as two different languages. He regarded the Konkani spoken in coastal Maharashtra as a dialect of Marathi and not as a dialect of Goan Konkani itself. In his opinion, Goan Konkani was also considered a dialect of Marathi because the religious literature used by the Hindus in Goa was not in Konkani itself, but in Marathi.

S. M. Katre's 1966 work, The Formation of Konkani, which utilised the instruments of modern historical and comparative linguistics across six typical Konkani dialects, showed the formation of Konkani to be distinct from that of Marathi.[5][75] Shenoi Goembab, who played a pivotal role in the Konkani revival movement, rallied against the pre-eminence of Marathi over Konkani amongst Hindus and Portuguese amongst Christians.

Goa's accession to India in 1961 came at a time when Indian states were being reorganised along linguistic lines. There were demands to merge Goa with Maharashtra. This was because Goa had a sizeable population of Marathi speakers and Konkani was also considered to be a dialect of Marathi by many. Konkani Goans were opposed to the move. The status of Konkani as an independent language or as a dialect of Marathi had a great political bearing on Goa's merger, which was settled by a plebiscite in 1967 (the Goa Opinion Poll).[5]

The Sahitya Akademi (a prominent literary organisation in India) recognised it as an independent language in 1975, and subsequently Konkani (in Devanagari script) was made the official language of Goa in 1987.

Script and dialect issues

The problems posed by multiple scripts and varying dialects have come as an impediment in the efforts to unite Konkani people. The Goa state's decision to use Devnagari as the official script and the Antruz dialect has been met with opposition both within Goa and outside it.[6] Critics contend that the Antruz dialect is unintelligible to most Goans, let alone other Konkani people outside Goa, and that Devanagari is used very little as compared to Romi Konkani in Goa or Konkani in the Kanarese script.[6] Prominent among the critics are Konkani Christians in Goa, who were at the forefront of the Konkani agitation in 1986–87 and have for a long time used the Roman script, including producing literature in Roman script. They are demanding that Roman script be given equal status to Devanagari.[76]

In Karnataka, which has the largest number of Konkani speakers, leading organisations and activists have similarly demanded that Kanarese script be made the medium of instruction for Konkani in local schools instead of Devanagari.[77] The government of Karnataka has given its approval for teaching of Konkani as an optional third language from 6th to 10th standard students either in Kannada or Devanagari scripts.[78]

Phonology

The Konkani language has 16 basic vowels (excluding an equal number of long vowels), 36 consonants, 5 semi-vowels, 3 sibilants, 1 aspirate, and many diphthongs. Like the other Indo-Aryan languages, it has both long and short vowels and syllables with long vowels may appear to be stressed. Different types of nasal vowels are a special feature of the Konkani language.[79]

- The palatal and alveolar stops are affricates. The palatal glides are truly palatal but otherwise the consonants in the palatal column are alveopalatal.[80]

- The voiced/voiceless contrasts are found only in the stops and affricates. The fricatives are all voiceless and the sonorants are all voiced.[80]

- The initial vowel-syllable is shortened after the aspirates and fricatives. Many speakers substitute unaspirated consonants for aspirates.[80]

- Aspirates in a non-initial position are rare and only occur in careful speech. Palatalisation/non-palatisation is found in all obstruents, except for palatal and alveolars. Where a palatalised alveolar is expected, a palatal is found instead. In the case of sonorants, only unaspirated consonants show this contrast, and among the glides only labeo-velar glides exhibit this. Vowels show a contrast between oral and nasal ones[80]

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i ĩ | u ũ | |

| Close-mid | e ẽ | ɵ ɵ̃ | o õ |

| Open-mid | ɛ ɛ̃ | ʌ ʌ̃ | ɔ ɔ̃ |

| Open | (æ) | a ã |

One of the most distinguishing features of Konkani phonology is the use of /ɵ/, the close-mid central vowel, instead of the schwa found in Hindustani and Marathi.

Whereas many Indian languages use only one of the three front vowels, represented by the Devanagari grapheme ए, Konkani uses three: /e/, /ɛ/ and /æ/.

Nasalizations exist for all vowels except for /ʌ/.

Grammar

Konkani grammar is similar to other Indo-Aryan languages. Notably, Konkani grammar is also influenced by Dravidian languages. Konkani is a language rich in morphology and syntax. It cannot be described as a stress-timed language, nor as a tonal language.[82]

- Speech can be classified into any of the following parts:[83]

- naam (noun)

- sarvanaam (pronoun)

- visheshan (adjective)

- kriyapad (verb)

- kriyavisheshana (adverb)

- ubhayanvayi avyaya

- shabdayogi avyaya

- kevalaprayogi avyaya

Like most of the Indo-Aryan languages, Konkani is an SOV language, meaning among other things that not only is the verb found at the end of the clause but also modifiers and complements tend to precede the head and postpositions are far more common than prepositions. In terms of syntax, Konkani is a head-last language, unlike English, which is an SVO language.[84]

- Almost all the verbs, adverbs, adjectives, and the avyayas are either tatsama or tadbhava.[83]

Verbs

Verbs are either tatsama or tadbhava:[83]

| Konkani verbs | Sanskrit/Prakrit Root | Translation | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| वाच vaach (tatsama) | वच् vach | read | ||

| आफय, आपय aaphay, aapay (tatsama) | आव्हय् aavhay | call, summon | ||

| रांध raandh (tatsama) | रांध् raandh | cook | ||

| बरय baray (tadbhav) | वर्णय् varnay | write | ||

| व्हर vhar (tadbhav) | हर har | take away | ||

| भक bhak (tadbhav) | भक्ष् bhaksh | eat | ||

| हेड hedd (tadbhav) | अट् att | roam | ||

| ल्हेव lhev (tadbhav) | लेह् leh | lick | ||

| शीन sheen (tadbhav) | छिन्न chinna | cut | ||

| Source: Koṅkaṇî Dhatukosh[83] | ||||

- Present indefinite of the auxiliary is fused with present participle of the primary verb, and the auxiliary is partially dropped.[83] When the southern dialects came in contact with Dravidian languages this difference became more prominent in dialects spoken in Karnataka whereas Goan Konkani still retains the original form.

For example, "I eat" and "I am eating" sound similar in Goan Konkani, due to loss of auxiliary in colloquial speech. "Hāv khātā" corresponds to "I am eating". On the other hand, in Karnataka Konkani "hāv khātā" corresponds to "I eat", and "hāv khātoāsā" or "hāv khāter āsā" means "I am eating".

- Out of eight grammatical cases, Konkani has totally lost the dative, the locative, and the ablative.[83] It has partially lost the accusative and the instrumental cases too.[83] So the preserved cases are: the nominative, the genitive, and the vocative case.[83]

Konkani Apabhramsha and Metathesis

- Like other languages, the Konkani language has three genders. Use of the neuter gender is quite unique in Konkani. During the Middle Ages, most of the Indo-Aryan languages lost their neuter gender, except Maharashtri, in which it is retained much more in Marathi than Konkani.[83] Gender in Konkani is purely grammatical and unconnected to sex.[83]

Metathesis is a characteristic of all the middle and modern Indo-Aryan languages including Konkani. Consider the Sanskrit word "स्नुषा" (daughter-in law). Here, the ष is dropped, and स्नु alone is utilised, स्नु-->स/नु and you get the word सुन (metathesis of ukar).[85]

- Unlike Sanskrit, anusvara has great importance in Konkani. A characteristic of Middle Indo-Aryan dialects, Konkani still retains the anusvara on the initial or final syllable.[83] Similarly visarga, is totally lost and is assimilated with उ and/or ओ. For example, in Sanskrit दीपः becomes दिवो and दुःख becomes दुख.

- Konkani retains the pitch accent, which is a direct derivative of Vedic accent, which probably would account for "nasalism" in Konkani.[83] The "Breathed" accent is retained in most of the tatsamas than the tadbhavas.[83] Declension also affects the accent.[83]

- Konkani has lost its passive voice, and now the transitive verbs in their perfects are equivalent to passives.

- Konkani has rejected ऋ, ॠ, ऌ, ॡ, ष, and क्ष, which are assimilated with र, ख, ह, श and स.[83]

- Sanskrit compound letters are avoided in Konkani. For example, in Sanskrit द्वे, प्राय, गृहस्थ, उद्योत become बे, पिराय, गिरेस्त, and उज्जो respectively in Konkani.[83]

Vocabulary

The vocabulary from Konkani comes from a number of sources. The main source is Prakrits. So Sanskrit as a whole has played a very important part in Konkani vocabulary. Konkani vocabulary is made of tatsama (Sanskrit loanwords without change), tadhbhava (evolved Sanskrit words), deshya (indigenous words) and antardeshya (foreign words). Other sources of vocabulary are Arabic, Persian, and Turkish. Finally Kannada, Marathi, and Portuguese have enriched its lexical content.[84]

Loanwords

Since Goa was a major trade centre for visiting Arabs and Turks, many Arabic and Persian words infiltrated the Konkani language.[45] A large number of Arabic and Persian words now form an integral part of Konkani vocabulary and are commonly used in day-to-day life; examples are karz (debt), fakt (only), dusman (enemy), and barik (thin).[45] Single and compound words are found wherein the original meaning has been changed or distorted. Examples include mustaiki (from Arabic mustaid, meaning "ready"), and kapan khairo ("eater of one's own shroud", meaning "a miser").

Most of the old Konkani Hindu literature does not show any influence from the Portuguese language. Even the spoken dialects by the majority of Goan Hindus has a very limited Portuguese influence. On the other hand, the spoken dialects of the Catholics from Goa (as well as the Canara to some extent), and their religious literature shows a strong Portuguese influence. They contain a number of Portuguese lexical items, but these are almost all religious terms. Even in the context of religious terminology, the missionaries adapted native terms associated with Hindu religious concepts. (For example, krupa for grace, Yamakunda for hell, Vaikuntha for paradise and so on). The syntax used by Goan Catholics in their literature shows a prominent Portuguese influence. As a result, many Portuguese loanwords are now commonly found in common Konkani speech.[86][87] The Portuguese influence is also evident in the Marathi–Konkani spoken in the former Northern Konkan district, Thane a variant of Konkani used by East Indians Catholic community.

Sanskritisation

Konkani is not highly Sanskritised like Marathi, but still retains Prakrit and apabhramsa structures, verbal forms, and vocabulary. Though the Goan Hindu dialect is highly Prakritised, numerous Sanskrit loanwords are found, while the Catholic dialect has historically drawn many terms from Portuguese. The Catholic literary dialect has now adopted Sanskritic vocabulary itself, and the Catholic Church has also adopted a Sanskritisation policy.[80] Despite the relative unfamiliarity of the recently introduced Sanskritic vocabulary to the new Catholic generations, there has not been wide resistance to the change.[80] On the other hand, southern Konkani dialects, having been influenced by Kannada − one of the most Sanskritised languages of Dravidian origin − have undergone re-Sanskritisation over time.[80]

Writing systems

Konkani has been compelled to become a language using a multiplicity of scripts, and not just one single script used everywhere. This has led to an outward splitting up of the same language, which is spoken and understood by all, despite some inevitable dialectal convergences.[88]

Past

The Brahmi script for Konkani fell into disuse.[89] Later, some inscriptions were written in old Nagari. However, owing to the Portuguese conquest in 1510 and the restrictions imposed by the inquisition, some early form of Devanagari was disused in Goa.[88] The Portuguese promulgated a law banning the use of Konkani and Nagari scripts.[20]

Another script, called Kandevi or Goykandi, was used in Goa since the times of the Kadambas, although it lost its popularity after the 17th century. Kandevi/Goykandi is very different from the Halekannada script, with strikingly similar features.[90] Unlike Halekannada, Kandevi/Goykandi letters were usually written with a distinctive horizontal bar, like the Nagari scripts. This script may have been evolved out of the Kadamba script, which was extensively used in Goa and Konkan.[91] The earliest known inscription in Devanagari dates to 1187 AD.[55] The Roman script has the oldest preserved and protected literary tradition, beginning from the 16th century.

Present

Konkani is written in five scripts: Devanagari, Roman, Kannada, Malayalam, and Perso-Arabic.[5] Because Devanagari is the official script used to write Konkani in Goa and Maharashtra, most Konkanis (especially Hindus) in those two states write the language in Devanagari. However, Konkani is widely written in the Roman script (called Romi Konkani) by many Konkanis, (especially Catholics).[46] This is because for many years, all Konkani literature was in the Latin script, and Catholic liturgy and other religious literature has always been in the Roman script. Most people of Karnataka use the Kannada script; however, the Saraswats of Karnataka use the Devanagari script in the North Kanara district. Malayalam script was used by the Konkani community in Kerala, but there has been a move towards the usage of the Devanagari script in recent years.[92] Konkani Muslims around Bhatkal taluka of Karnataka use Arabic script to write Konkani. There has been to trend towards the usage of the Arabic script among Muslim communities; this coincides with them mixing more Urdu and Arabic words into their Konkani dialects. When the Sahitya Akademi recognised Konkani in 1975 as an independent and literary language, one of the important factors was the literary heritage of Romi Konkani since the year 1556. However, after Konkani in the Devanagari script was made the official language of Goa in 1987, the Sahitya Akademi has supported only writers in the Devanagari script. For a very long time there has been a rising demand for official recognition of Romi Konkani by Catholics in Goa because a sizeable population of the people in Goa use the Roman script. Also a lot of the content on the Internet and the staging of the famed Tiatr is written in Romi Konkani. In January 2013, the Goa Bench of the Bombay High Court issued a notice to the state government on a Public Interest Litigation filed by the Romi Lipi Action Front seeking to amend the Official Language Act to grant official language status to Romi Konkani but has not yet been granted.[93]

Alphabet or the Varṇamāḷha

The vowels, consonants, and their arrangement are as follows:[94]

| अ | a /ɐ/ |

आ | ā /ɑː/ |

इ | i /i/ |

ई | ī /iː/ |

उ | u /u/ |

ऊ | ū /uː/ |

ए | e /eː/ |

ऐ | ai /aːi/ |

ओ | o /oː/ |

औ | au /aːu/ |

अं | aṃ /ⁿ/ |

अः | aḥ /h/ |

| क | ka /k/ |

ख | kha /kʰ/ |

ग | ga /ɡ/ |

घ | gha /ɡʱ/ |

ङ | ṅa /ŋ/ |

| च | ca /c, t͡ʃ/ |

छ | cha /cʰ, t͡ʃʰ/ |

ज | ja /ɟ, d͡ʒ/ |

झ | jha /ɟʱ, d͡ʒʱ/ |

ञ | ña /ɲ/ |

| ट | ṭa /ʈ/ |

ठ | ṭha /ʈʰ/ |

ड | ḍa /ɖ/ |

ढ | ḍha /ɖʱ/ |

ण | ṇa /ɳ/ |

| त | ta /t̪/ |

थ | tha /t̪ʰ/ |

द | da /d̪/ |

ध | dha /d̪ʱ/ |

न | na /n/ |

| प | pa /p/ |

फ | pha /pʰ/ |

ब | ba /b/ |

भ | bha /bʱ/ |

म | ma /m/ |

| य | ya /j/ |

र | ra /r/ |

ल | la /l/ |

व | va /ʋ/ | ||

| ष | ṣa /ʂ/ |

श | śa /ɕ, ʃ/ |

स | sa /s/ |

ह | ha /ɦ/ | ||

| ळ | ḷha //ɭʱ// |

क्ष | kṣa /kʃ/ |

ज्ञ | jña /ɟʝɲ/ |

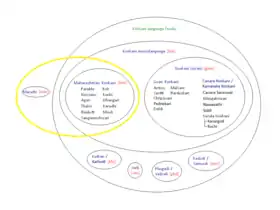

Dialects

Konkani, despite having a small population, shows a very high number of dialects. The dialect tree structure of Konkani can easily be classified according to the region, religion, caste, and local tongue influence.[5]

Based on the historical events and cultural ties of the speakers, N. G. Kalelkar has broadly classified the dialects into three main groups:[5]

- Northern Konkani: Dialects spoken in the Sindhudurga district of Maharashtra with strong cultural ties to Marathi; i.e. Malvani

- Central Konkani: Dialects in Goa and Northern Karnataka, where Konkani came in close contact with Portuguese language and culture and Kannada.

- Southern Konkani: Dialects spoken in the Canara region (Mangalore,Udupi) of Karnataka and Kasaragod of Kerala, which came in close contact with Tulu and Kannada.

Goan Konkani

- Under the ISO 639-3 classification, all the dialects of the Konkani language except for those that come under Maharashtrian Konkani are collectively assigned the language code ISO 639:gom and called Goan Konkani. In this context, it includes dialects spoken outside the state of Goa, such as Mangalorean Konkani, Chitpavani Konkani Malvani Konkani and Karwari Konkani.

- In common usage, Goan Konkani refers collectively only to those dialects of Konkani spoken primarily in the state of Goa, e.g. the Antruz, Bardeskari and Saxtti dialects.

Organisations

There are organisations working for Konkani but, primarily, these were restricted to individual communities. The All India Konkani Parishad founded on 8 July 1939, provided a common ground for Konkani people from all regions.[95] A new organisation known as Vishwa Konkani Parishad, which aims to be an all-inclusive and pluralistic umbrella organisation for Konkanis around the world, was founded on 11 September 2005.

Mandd Sobhann is the premier organisation that is striving hard to preserve, promote, propagate, and enrich the Konkani language and culture. It all began with the experiment called ‘Mandd Sobhann’ – a search for a Konkani identity in Konkani music in 30 November 1986 at Mangalore. What began as a performance titled ‘Mandd Sobhann’, grew into a movement of revival and rejuvenation of Konkani culture; and solidified into an organization called Mandd Sobhann. Today, Mandd Sobhann boasts of all these 3 identities namely - a performance, a movement and an organization.https://www.manddsobhann.org/

The Konkan Daiz Yatra, started in 1939 in Mumbai, is the oldest Konkani organisation. The Konkani Bhasha Mandal was born in Mumbai on 5 April 1942, during the Third Adhiveshan of All India Konkani Parishad. On 28 December 1984, Goa Konkani Akademi (GKA) was founded by the government of Goa to promote Konkani language, literature, and culture.[96] The Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr (TSKK) is a popular research institute based in the Goan capital Panaji. It works on issues related to the Konkani language, literature, culture, and education.[97] The Dalgado Konkani Academy is a popular Konkani organisation based in Panaji.

The Konkani Triveni Kala Sangam is one more famed Konkani organisation in Mumbai, which is engaged in the vocation of patronising Konkani language through the theatre movement. The government of Karnataka established the Karnataka Konkani Sahitya Akademy on 20 April 1994.[98] The Konkani Ekvott is an umbrella organisation of the Konkani bodies in Goa.

The First World Konkani Convention was held in Mangalore in December 1995. The Konkani Language and Cultural Foundation came into being immediately after the World Konkani Convention in 1995.[99]

The World Konkani Centre built on a three-acre plot called Konkani Gaon (Konkani Village) at Shakti Nagar, Mangalore was inaugurated on 17 January 2009,[100] "to serve as a nodal agency for the preservation and overall development of Konkani language, art, and culture involving all the Konkani people the world over.”

The North American Konkani Association (NAKA) serves to unite Konkanis across the United States and Canada. It serves as a parent organization for smaller Konkani associations in various states. Furthermore, the Konkani Young Adult Group serves as a platform under NAKA to allow young adults across America (18+) of Konkani descent to meet each other and celebrate their heritage. Every 2-4 years, a Konkani Sammelan, where Konkanis from across the continent attend, is held in a different city in the US. A Konkani Youth Convention is held yearly. Past locations have included NYC and Atlanta; the upcoming youth convention is slated to be held in Chicago, IL in June.

Literature

.jpg.webp)

During the Goa Inquisition which commenced in 1560, all books found in the Konkani language were burnt, and it is possible that old Konkani literature was destroyed as a consequence.[101]

The earliest writer in the history of Konkani language known today is Krishnadas Shama from Quelossim in Goa. He began writing 25 April 1526, and he authored Ramayana, Mahabharata, and Krishnacharitrakatha in prose style. The manuscripts have not been found, although transliterations in Roman script are found in Braga in Portugal. The script used by him for his work is not known.[102]

The first known printed book in Konkani was written by an English Jesuit priest, Fr. Thomas Stephens in 1622, and entitled Doutrina Christam em Lingoa Bramana Canarim (Old Portuguese for: Christian Doctrine in the Canarese Brahman Language). The first book exclusively on Konkani grammar, Arte da Lingoa Canarim, was printed in 1640 by Father Stephens in Portuguese.[23]

Konkani media

Radio

All India Radio started broadcasting Konkani news and other services. Radio Goa Pangim started a Konkani broadcast in 1945. AIR Mumbai and Dharwad later started Konkani broadcasts in the years 1952 and 1965 respectively. Portuguese Radio, Lisbon started services in 1955 for India, East Africa, and Portugal. Similarly Trivandrum, Alleppey, Trichur, and Calicut AIR centres started Konkani broadcasts.[23]

In Manglore and Udupi, many weekly news magazines are published in Konkani. Rakno, Daize, and a few others are very famous among the Christian community. Every Roman Catholic parish will publish 3–4 magazines in a year.

Print

"Udentichem Sallok" was the first Konkani periodical published in 1888, from Poona, by Eduardo Bruno de Souza. It started as a monthly and then as a fortnightly. It closed down in 1894.[103]

Dailies

"Sanjechem Nokhetr" was started in 1907, by B. F. Cabral, in 1907 in Bombay, and is the first Concanim newspaper. It contained detailed news of Bombay, as it was published from there. In 1982, "Novem Goem" was a daily edited by Gurunath Kelekar, Dr. F. M. Rebello and Felisio Cardozo. It was started due to people's initiative. In 1989, Fr. Freddy J. da Costa, began a Konkani daily "Goencho Avaz". It became a monthly after one and a half year. Presently there is just a single Konkani daily newspaper, called Bhaangar Bhuin. For a long time, there was another Konkani daily, Sunaparant, which was published in Panjim.

Weeklies

"O Luzo-Concanim" was a Concanim (Konkani)- Portuguese bilingual weekly, begun in 1891, by Aleixo Caitano José Francisco. From 1892 to 1897, "A Luz", "O Bombaim Esse", "A Lua", "O Intra Jijent" and "O Opinião Nacional" were bilingual Concanim- Portuguese weeklies published. In 1907 "O Goano" was putblished from Bombay, by Honorato Furtado and Francis Xavier Furtado. It was a trilingual weekly in Portuguese, Konkani and English.

The Society of the Missionaries of Saint Francis Xavier, publish the Konkani weekly (satollem) named Vauraddeancho Ixtt, from Pilar. It was started in 1933 by Fr. Arsencio Fernandes and Fr. Graciano Moraes. Amcho Avaz is a weekly which began in 2013, in Panjim.

Fortnightly

There is a fortnightly published newspaper since 2007 called Kodial Khaber Edited by Venkatesh Baliga Mavinakurve and Published by: Baliga Publications, Mangalore. "ARSO" Konkani - Kannada Fortnightly is being published from 2013 from Mangalore. Editor / Publisher : H M Pernal

Monthlies

Katolik Sovostkai was stated in 1907 by Roldão Noronha. It later became a fortnightly before ceasing publication. In 1912 "Konakn Magazine" was started by Joaquim Campos.

Dor Mhoineachi Rotti is the oldest running current Konkani periodical. It is dedicated to the spreading of the devotion to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, and was initially named Dor Muineachi Rotti Povitra Jesucha Calzachem Devoçãõ Vaddounchi. Note that the til (tilde mark) over ãõ in Devoçãõ is one single til. Fr. Vincent Lobo, from Sangolda in Goa, who was then curator at the St. Patrick's Church in Karachi, began it in 1915, to feed the spiritual thirst and hunger of the large number of Konkani speaking people there, on noticing the absence of Konkani spiritual literature. The name was changed subsequently to "Dor Muiniachi Rotti, Concanim Messenger of the Sacred Heart". On Fr. Vincent Lobo's passing away on 11 November 1922, Fr. António Ludovico Pereira, also from Sangolda, took over the responsibility. Dor Mhoineachi Rotti had an estimated readership of around 12,000 people then. After the passing away of Fr. António Ludovico Pereira on 26 July 1936, Fr. Antanasio Moniz, from Verna, took over. On his passing away in 1953, Fr. Elias D'Souza, from Bodiem, Tivim in Goa became the fourth editor of Dor Mhoineachi Rotti. After shifting to Velha Goa in Goa around 1964, Fr. Moreno de Souza was editor for around 42 years. Presently the Dor Mhuineachi Rotti is owned by the Jesuits in Goa, edited by Fr. Vasco do Rego, S. J. and printed and published by Fr. Jose Silveira, S.J. on behalf of the Provincial Superior of the Jesuits in Goa. Dor Mhoineachi Rotti will complete 100 years on 1 January 2015.

Gulab is a monthly from Goa. It was started by late Fr. Freddy J. da Costa in 1983, and was printed in colour, then uncommon. "Bimb"", "Jivit", "Panchkadayi" and ""Poddbimb" are some other monthlies.

Konkani periodicals published in Goa include Vauraddeancho Ixtt (Roman script, weekly), Gulab (Roman script, monthly), Bimb (Devanagari script, monthly), Panchkadayi (Kannada script, monthly) and Poddbimb (Roman script, monthly). Konkani periodicals published in Mangalore include "Raknno" (Kannada script, weekly), "DIVO" (Kannada Script, weekly from Mumbai), "Kutmacho Sevak" (Kannada script, monthly), "Dirvem" (Kannada script, monthly),"Amcho Sandesh" (Kannada script, monthly) and "Kajulo" (Kannda script, children's magazine, monthly). Konkani periodical published in Udupi include "Uzwad" (Kannada script, monthly) and Naman Ballok Jezu (Kannada script, monthly). Ekvottavorvim Uzvadd (Devanagari Script, monthly) is published from Belgaum since 1998. Panchkadayi Konkani Monthly magazine from Manipal since 1967.

Digital/Websites/E-Books/Audio Books in Konkani

The first complete literary website in Konkani started in 2001 using Kannada script was www.maaibhaas.com by Naveen Sequeira of Brahmavara. In 2003 www.daaiz.com started by Valley Quadros Ajekar from Kuwait, this literary portal was instrumental in creating a wider range of readers across the globe, apart from various columns, literary contests, through Ashawadi Prakashan, he published several books in Konkani, including the first e-book 'Sagorachea Vattecheo Zori' released by Gerry DMello Bendur in 2005 at Karkala.

www.poinnari.com is the first literary webportal in Konkani using three scripts (Kannada, Nagari and Romi), started in 2015, is also conducted the first National level literary contest in dual scripts in Konkani in 2017.

'Sagorachea Vattecheo Zori' is the first e-book in Konkani, a compilation of 100 poems digitally published by www.daaiz.com and digitally published in 2005 by Ashawadi Prakashan in Karkala.

'Kathadaaiz' is the first digital audio book digitally published in 2018 by www.poinnari.com. This audio book is also available in the YouTube channel of Ashawari Prakashan.

'Pattim Gamvak' is the first e-Novel written in Kannada script Konkani in 2002 by Valley Quadros Ajekar from Kuwait, published in www.maaibhaas.com in 2002-3.

'Veez' is the first digital weekly in Konkani, started in 2018 by Dr.Austine D'Souza Prabhu in Chicago, USA. Veez is the only magazine publishing Konkani in 4 scripts; Kannada, Nagari, Romi and Malayalam.

Television

The Doordarshan centre in Panjim produces Konkani programs, which are broadcast in the evening. Many local Goan channels also broadcast Konkani television programs. These include: Prudent Media, Goa 365, HCN, RDX Goa, and others.

Konkani film

In popular culture

Many Konkani songs of the Goan fisher-folk appear recurrently in a number of Hindi films. Many Hindi movies feature characters with a Goan Catholic accent. A famous song from the 1957 movie Aasha, contains the Konkani words "mhaka naka" and became extremely popular. Children were chanting "Eeny, meeny, miny, moe", which inspired C Ramchandra and his assistant John Gomes to create the first line of the song, "Eena Meena Deeka, De Dai Damanika". Gomes, who was a Goan, added the words "maka naka" (Konkani for "I don't want"). They kept on adding more nonsense rhymes until they ended with "Rum pum po!".[104][105]

An international ad campaign by Nike for the 2007 Cricket World Cup featured a Konkani song "Rav Patrao Rav" as the background theme. It was based on the tune of an older song "Bebdo", composed by Chris Perry and sung by Lorna Cordeiro. The new lyrics were written by Agnello Dias (who worked in the ad agency that made the ad), recomposed by Ram Sampat, and sung by Ella Castellino.

A Konkani cultural event, Konkani Nirantari organised by Mandd Sobhann, was held in Mangalore on 26 and 27 January 2008 , and entered the Guinness Book of World Records for holding a 40-hour-long non-stop musical singing marathon, beating a Brazilian musical troupe who had previously held the record of singing non-stop for 36 hours.[106]

See also

- Canara Konkani

- Konkani in the Roman script

- Konkani Language Agitation

- Konkani people

- Konkani phonology

- Konkani Poets

- Konkani Script

- Konkani words from other languages

- Languages of India

- Languages with official status in India

- List of Indian languages by total speakers

- Maharashtri

- Malvani dialect

- Malvani people

- Marathi–Konkani languages

- Paisaci

- Sahitya Akademi Award to Konkani Writers

- World Konkani Centre

- World Konkani Hall of Fame

Footnotes

- Devanagari has been promulgated as the official script.

- Roman script is not mandated as an official script by law. However, an ordinance passed by the government of Goa allows the use of Roman script for official communication. This ordinance has been put into effect by various ministries in varying degrees. For example, the Goa Panchayat Rules, 1996 stipulate that the various forms used in the election process must be in both the Roman and Devanagari script.

- The use of Kannada script is not mandated by any law or ordinance. However, in the state of Karnataka, Konkani is used in the Kannada script instead of the Devanagari script.

- Konkani is a name given to a group of several cognate dialects spoken along the narrow strip of land called Konkan, on the western coast of India. Geographically, Konkan is defined roughly as the area between the Daman Ganga River to the north and the Kali River to the south; the north–south length is about 650 km and the east–west breadth is about 50 km. The dialect spoken in Goa, coastal Karnataka and in some parts of Northern Kerala has distinct features and is rightly identified as a separate language called Konkani.[8]

- Chavundaraya was the military chief of the Ganga dynasty-era King Gangaraya. This inscription on the Bahubali statue draws attention to a Basadi (Jain Temple) initially built by him and then modified by Gangaraya in the 12th century AD. Ref: S. Settar in Adiga (2006), p256

- The above inscription has been quite controversial, and is touted as old-Marathi. But the distinctive instrumental viyalem ending of the verb is the hallmark of the Konkani language, and the verb sutatale or sutatalap is not prevalent in Marathi. So linguists and historians such as S.B. Kulkarni of Nagpur University, Dr V.P. Chavan (former vice-president of the Anthropological Society of Mumbai), and others have thus concluded that it is Konkani.

References

- Whiteley, Wilfred Howell (1974). Language in Kenya. Oxford University Press. p. 589.

- Kurzon, Denis (2004). Where East looks West: success in English in Goa and on the Konkan Coast Volume 125 of Multilingual matters. Multilingual Matters. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-85359-673-5.

- "Statement 1: Abstract of speakers' strength of languages and mother tongues - 2011". www.censusindia.gov.in. Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India. Retrieved 7 July 2018.

- Kapoor, Subodh (10 April 2002). The Indian Encyclopaedia: La Behmen-Maheya. Cosmo Publications. ISBN 9788177552713 – via Google Books.

- Mother Tongue blues – Madhavi Sardesai

- "Goanet :: Where Goans connect". 24 July 2011. Archived from the original on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 18 September 2020.

- "The Goa Daman and Diu Official Language Act" (PDF). Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2010.

- "Konkani Language and History". Language Information Service. 6 July 2009. Retrieved 18 March 2011.

- "Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages- India/ States/ Union Territories – 2001 Census".

- Administrator. "Department of Tourism, Government of Goa, India - Language". goatourism.gov.in.

- Cardona, Jain, George, Dhanesh (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 1088 pages (see page:803–804). ISBN 9780415772945.

- Cardona, Jain, George, Dhanesh (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 1088 pages (see page:834). ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

- "'Konkanis to be blamed for lingo's precarious state' - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Menezes, Vivek (8 September 2017). "Konkani: a language in crisis". mint. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- Masica, Colin P. (1991). The Indo-Aryan languages. p. 449.

- Menezes, Armando (1970). Essays on Konkani language and literature: Professor Armando Menezes felicitation volume. Konkani Sahitya Prakashan. pp. 118 pages (see page:2).

- Janardhan, Pandarinath Bhuvanendra (1991). A Higher Konkani grammar. P.B. Janardhan. pp. 540 pages.

- V.J.P. Saldanha. Sahitya Akademi. 2004. pp. 81 pages. ISBN 9788126020287.

- M. Saldanha 717. J. Thekkedath, however, quotes Jose Pereira to the following effect: "A lay brother of the College of St Paul around 1563 composed the first grammar of Konkani. His work was continued by Fr Henry Henriques and later by Fr Thomas Stephens. The grammar of Fr Stephens was ready in manuscript form before the year 1619." (Jose Pereira, ed., "Gaspar de S. Miguel’s Arte da Lingoa Canarim, parte 2a, Sintaxis copiossisima na lingoa Bramana e pollida," Journal of the University of Bombay [Sept. 1967] 3–5, as cited in J. Thekkedath, History of Christianity in India, vol. II: From the Middle of the Sixteenth to the End of the Seventeenth Century (1542–1700) [Bangalore: TPI for CHAI, 1982] 409).

- Sardessai, Manohar Rai (2000). "Missionary period". A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 30–70.

- Arte Canarina na lingoa do Norte. Anonymous MS, edited by Cunha Rivara under the title: Gramática da Lingua Concani no dialecto do Norte, composta no seculo XVII por um Missionário Portugues; e agora pela primeira vez dada à estampa (Nova Goa: Imprensa Nacional, 1858). Cunha Rivara suggested that the author was either a Franciscan or a Jesuit residing in Thana on the island of Salcete; hence the reference to a ‘Portuguese missionary’ in the title.

- Mariano Saldanha, "História de Gramática Concani," Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies 8 (1935–37) 715. See also M. L. SarDessai, A History of Konkani Literature: From 1500 to 1992 (New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi, 2000) 42–43.

- Saradesāya, Manohararāya (2000). A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. pp. 1–3. ISBN 978-81-7201-664-7.

- Singh, K.S. (1997). People of India Vol. III : Scheduled Tribes. Oxford University Press. pp. 522, 523. ISBN 978-0-19-564253-7.

- Indian Anthropological Society (1986). Journal of the Indian Anthropological Society, Volumes 21–22. Indian Anthropological Society. pp. See page 75.

- Enthoven, Reginald Edward (1990). The tribes and castes of Bombay, Volume 1. Asian Educational Services. pp. 195–198. ISBN 978-81-206-0630-2.

- Gomes, Olivinho (1997). Medieval Indian literature: an anthology, Volume 3 Medieval Indian Literature: An Anthology, K. Ayyappapanicker. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 256–290. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- Sinai Dhume, Anant Ramkrishna (1986). The cultural history of Goa from 10000 B.C.-1352 A.D. Ramesh Anant S. Dhume. pp. 355 pages.

- India. Office of the Registrar General (1961). Census of India, 1961, Volume 1, Issue 1 Census of India, 1961, India. Office of the Registrar General. Manager of Publications. p. 67.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003)The Dravidian Languages Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-77111-0 at pp. 40–41.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003) The Dravidian Languages Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-77111-0 at pp. 12.

- Encyclopaedia of Tamil Literature: Introductory articles. Institute of Asian Studies. 1990. pp. See Page 45.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003) The Dravidian Languages Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-77111-0 at pp.4–6.

- Ayyappapanicker, K. Medieval Indian literature: an anthology. Volume 3. Sahitya Akademi. p. 256.

- James Hastings; John Alexander Selbie; Louis Herbert Gray (1919). Encyclopædia of religion and ethics, Volume 10. T. & T. Clark. pp. see page 45.

- Wilford, Major F. (1812). "II". Asiatic researches or transactions of the society instituted in Bengal. Eleventh. p. 93.

- Gomes, Olivinho (1999). Old Konkani language and literature: the Portuguese role. Konkani Sorospot Prakashan, 1999. pp. 28, 29.

- Southworth, Franklin C. (2005). Linguistic archaeology of South Asia. Routledge. pp. 369 pages. ISBN 978-0-415-33323-8.

- "Roots of Konkani" (in English and Konkani). Goa Konkani Akademi. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2009.

- Ayyappapanicker, K. Medieval Indian literature: an anthology. Volume 3. Sahitya Akademi. p. 246.

- Bhat, V. Nithyanantha. The Konkani language: historical and linguistic perspectives. Sukṛtīndra Oriental Research Institute. p. 5.

- Bhat, V. Nithyanantha. The Konkani language: historical and linguistic perspectives. Sukṛtīndra Oriental Research Institute. p. 12.

- Sinai Dhume, Ananta Ramakrishna (2009). The cultural history of Goa from 10000 BC to 1352 AD. Panaji: Broadway book centre. pp. Chapter 6(pages 202–257). ISBN 9788190571678.

- Mitragotri, Vithal Raghavendra (1999). A socio-cultural history of Goa from the Bhojas to the Vijayanagara. Institute Menezes Braganza, 1999. p. 268.

- Sardessai, Manoharray (2000). "The foreign influence". A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992 (1st ed.). Sahitya Akademi. pp. 21–30. ISBN 978-81-7201-664-7.

- George, Cardona; Dhanesh Jain. The Indo-Aryan Languages. p. 840.

- ndo-Iranian journal. Mouton, 1977.

- Gune, V.T (1979). Gazetteer of the union territory of Goa Daman and Diu, part 3, Diu. Gazetteer of the union territory of Goa. p. 21.

- Saradesāya Publisher, Manohararāya (2000). A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 317 pages. ISBN 978-81-7201-664-7.

- Pereira, José (1977). Monolithic Jinas. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. see pages 47–48. ISBN 9788120823976.

- Chavan, Mahavir S. (1 April 2008). "Jainism Articles and Essays: The First Marathi Inscription at Shravanbelagola".

- Corpus Inscriptions Indicarum, p. 163, verses 22-24, https://archive.org/stream/corpusinscriptio014678mbp#page/n395/mode/2up

- D'Souza, Edwin. V.J.P. Saldanha. pp. 3–5.

- Da Cruz, Antonio (1974). Goa: men and matters. s.n., 1974. p. 321.

- Saradesāya, Manohararāya (2000). A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. New Delhi: Kendra Sahitya Akademi. pp. 8–10. ISBN 978-81-7201-664-7.

- Maffei, Agnelus F.X. (2003). A Konkani grammar. Asian Educational Services. p. 83. ISBN 978-81-206-0087-4.

- "Konkani History". Kokaniz.com. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- Shah, Anish M.; et al. (15 July 2011). "Indian Siddis: African Descendants with Indian Admixture". American Journal of Human Genetics. 89 (1): 154–161. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2011.05.030. PMC 3135801. PMID 21741027.

- "Goa News -". Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Goa News -". Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Kelekar 2003:14.

- Kurzon, Dennis. Where East looks West: success in English in Goa and on the Konkan Coast. pp. 25–30.

- "Abstract of Speakers' strengths of languages and mother tongues – 2001". Census of India. Archived from the original on 6 February 2012. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- "Census of India 2011, LANGUAGE" (PDF).

- "Mangaluru : MLC Ivan D'Souza told not to speak in Konkani". Mangalore Information. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "MLC Ivan D'Souza attempts to speak Konkani in the State Legislative Council". Kannadiga World. 17 December 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "MLC Ivan D'souza made a attempt to speak Konkani in Council". Mega Media News. 17 December 2014. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Ivan D'souza's determined effort to speak Konkani in Council, hindered by chairman". Divine World. 17 December 2014. Archived from the original on 18 January 2015. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Bangalore: Kannada Activists Target Konkani Catholics Again at Sadbhavana". Daijiworld Media Network. 2 December 2012. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- D'Souza, Edwin (19 November 2012). "Bangalore: Kannada Activists Attack Konkani Catholics over Language Issue". Dajiworld Media. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Soares, Jaison (3 December 2012). "Konkani Catholics targeted in Bangalore". Udupi Today Media Network. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Mysore, Shimoga districts demand mass in Konkani". The Times of India (Bangalore). 7 March 2013. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- "Bishop Moras Named New Archbishop Of Troubled Bangalore Archdiocese". UCA News. 23 July 2004. Retrieved 14 January 2015.

- Saldanha-Shet, I J (25 March 2014). "An exquisite edifice in Mangalore" (Bangalore). Deccan Herald. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- "Language in India". Language in India. 3 May 2001. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- PTI (20 February 2007). "Goa group wants Konkani in Roman script". Articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- "Kannada script must be used to teach Konkani". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 14 March 2006.

- "News headlines". Daijiworld.com. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Bhat, V. Nithyanantha. The Konkani language: historical and linguistic perspectives (in English and Konkani). Sukṛtīndra Oriental Research Institute. pp. 43, 44.

- Cardona, George (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. p. 1088. ISBN 978-0-415-77294-5.

-

- Masica, Colin (1991), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 97, ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Caroline Menezes. "The question of Konkani?" (PDF). Project D2, Typology of Information Structure". Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 April 2008. Retrieved 10 February 2008.

- Janardhan, Pandarinath Bhuvanendra (1991). A Higher Konkani grammar. Foreign Language Study / Indic Languages Konkani language About (in English and Konkani). P.B. Janardhan. pp. 540 pages.

- Kurzon, Dennis (2004). Where East looks West: success in English in Goa and on the Konkan Coast Volume 125 of Multilingual matters. Multilingual Matters. p. 158. ISBN 9781853596735.

- Pandarinath, Bhuvanendra Janardhan (1991). A Higher Konkani grammar. P.B. Janardhan. pp. 540 pages (see pages:377 and 384).

- Anvita Abbi; R. S. Gupta; Ayesha Kidwai (2001). Linguistic structure and language dynamics in South Asia: papers from the proceedings of SALA XVIII Roundtable. Motilal Banarsidass, 2001 – Language Arts & Disciplines -. pp. 409 pages(Chapter 4 Portuguese influence on Konkani syntax). ISBN 9788120817654.

- List of loanwords in Konkani

- Sardessai, Manohar Rai (2000). "Missionary period". A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. Sahitya Akademi. pp. 9–10.

- Bhat, V. Nithyanantha (2004). V. Nithyanantha Bhat, Ela Sunītā (ed.). The Konkani language: historical and linguistic perspectives. Konkani language. Volume 10 of Sukṛtīndra Indological series. Sukṛtīndra Oriental Research Institute. p. 52.

- Indian archives. Volume 34. National Archives of India. p. 1985.

- Ghantkar, Gajanana (1993). History of Goa through Gõykanadi script (in English, Konkani, Marathi, and Kannada). pp. Page x.

- George, Cardona; Dhanesh Jain. The Indo-Aryan Languages. p. 804.

- "HC notice to govt on Romi script". The Times of India. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Gomanta Bharati, yatta payali, Published by GOA BOARD OF SECONDARY AND HIGHER SECONDARY EDUCATION ALTO BETIM, page number:11

- "Goanobserver.com". www77.goanobserver.com. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011.

- "Goa Konkani Akademi – promoting the development of Konkani language, literature and culture". Goa Konkani Akademi. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- "Thomas Stephens Konknni Kendr". Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- "Konkani". Kalaangann, Mandd Sobhann (The Konkani Heritage Centre). Archived from the original on 24 February 2008. Retrieved 16 June 2008.

- "Encouragement for Vishwa Konkani Kendra". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 6 September 2005.

- "Mangalore Goa CM Dedicates World Konkani Centre to Konkani People". Daijiworld.com. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- Saradesāya, Manohararāya (2000). A history of Konkani literature: from 1500 to 1992. Sahitya Akademi. p. 317. ISBN 978-81-7201-664-7.

- Bhembre, Uday (September 2009). Konkani bhashetalo paylo sahityakar:Krishnadas Shama. Sunaparant Goa. pp. 55–57.

- "Romi Konknni: Hanging on a Cliff by Fr. Peter Raposo". Behind the News: Voices from Goa's Press. pp. 183–185.

- Joshi, Lalit Mohan (2002). Bollywood: popular Indian cinema. Dakini Books. pp. 351 pages (see page:66).

- Ashwin Panemangalore (16 June 2006). "The story of 'Eena Meena Deeka'". DNA. Archived from the original on 30 September 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2007.

- "Mangalore: Guinness Adjudicator Hopeful of Certifying Konkani Nirantari". Daijiworld Media Pvt Ltd Mangalore. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

Further reading

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Konkani. |

| Goan Konkani edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

| Look up Konkani in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Konkani phrasebook. |

- Vauraddeancho Ixtt, Konkani language site

- Konkani News, Konkani language site

- Kital, Konkani language site

- Chilume.com, Konkani Literature

- Niz Goenkar, Konkani-English bilingual site

- Learn Goan Konkani online

- Read Konkani News online

- Learn Mangalorean GSB Konkani online

- Learn Mangalorean Catholic Konkani online

- An excellent article on Konkani history and literature by Goa Konkani Academi

- Online Manglorean Konkani Dictionary Project

- Online Konkani (GSB) dictionary

- World Konkani Centre, Mangalore

- Konkanverter-Konkani script conversion utility