Roman Question

The Roman Question (Italian: Questione romana; Latin: Quaestio Romana)[1] was a dispute regarding the temporal power of the popes as rulers of a civil territory in the context of the Italian Risorgimento. It ended with the Lateran Pacts between King Victor Emmanuel III of Italy and Pope Pius XI in 1929.

|

| This article is part of a series on |

| Vatican City |

|---|

International interest

On 9 February 1849, the Roman Republic took over the government of the Papal States. In the following July, an intervention by French troops restored Pope Pius IX to power, making the Roman Question a hotly debated one even in the internal politics of France.[2]

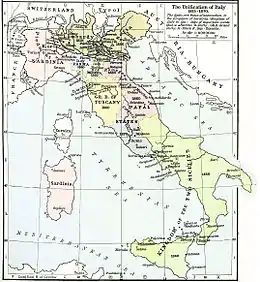

In July 1859, after France and Austria made an agreement that ended the short Second Italian War of Independence, an article headed "The Roman Question" in the Westminster Review expressed the opinion that the Papal States should be deprived of the Adriatic provinces and be restricted to the territory around Rome.[3] This became a reality in the following year, when most of the Papal States were annexed by what became the Kingdom of Italy.

Claims of the Kingdom of Italy

On February 18, 1861, the deputies of the first Italian Parliament assembled in Turin. On March 17, 1861, the Parliament proclaimed Victor Emmanuel II King of Italy, and on March 27, 1861, Rome was declared Capital of the Kingdom of Italy. However, the Italian Government could not take its seat in Rome because a French garrison (which had overthrown the Roman Republic), maintained there by Napoleon III of France, commanded by general Christophe Léon Louis Juchault de Lamoricière, was defending Pope Pius IX. Following the signing of the September Convention, the seat of government was moved from Turin to Florence in 1865.

The Pope remained totally opposed to the designs on Rome of Italian nationalism. Beginning in December 1869, the First Vatican Council was held in the city. Some historians have argued that its proclamation of the doctrine of papal infallibility in July 1870 had political as well as theological causes.

In July 1870, the Franco-Prussian War began. In early August, Napoleon III recalled his garrison from Rome and could no longer protect what remained of the Papal States. Widespread public demonstrations demanded that the Italian government take Rome. The Italian government took no direct action until the collapse of Napoleon at the battle of Sedan. King Victor Emmanuel II then sent Count Gustavo Ponza di San Martino to Pius IX with a personal letter offering a proposal that would have allowed the peaceful entry of the Italian Army into Rome, under the guise of protecting the pope.

According to Raffaele De Cesare:

The Pope's reception of San Martino [10 September 1870] was unfriendly. Pius IX allowed violent outbursts to escape him. Throwing the King's letter upon the table he exclaimed, "Fine loyalty! You are all a set of vipers, of whited sepulchres, and wanting in faith." He was perhaps alluding to other letters received from the King. After, growing calmer, he exclaimed: "I am no prophet, nor son of a prophet, but I tell you, you will never enter Rome!" San Martino was so mortified that he left the next day.[4]

The Italian army, commanded by General Raffaele Cadorna, crossed the frontier on 11 September and advanced slowly toward Rome, hoping that an unopposed entry could be negotiated. The Italian army reached the Aurelian Walls on 19 September and placed Rome under a state of siege. Pius IX decided that the surrender of the city would be granted only after his troops had put up a token resistance, enough to make it plain that the takeover was not freely accepted. On 20 September, after a cannonade of three hours had breached the Aurelian Walls at Porta Pia, the Bersaglieri entered Rome (see capture of Rome). Forty-nine Italian soldiers and 19 Papal Zouaves died. Rome and the region of Lazio were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy after a plebiscite.

Again, according to Raffaele De Cesare:

The Roman question was the stone tied to Napoleon's feet—that dragged him into the abyss. He never forgot, even in August 1870, a month before Sedan, that he was a sovereign of a Catholic country, that he had been made emperor, and was supported by the votes of the conservatives and the influence of the clergy; and that it was his supreme duty not to abandon the pontiff.... For twenty years Napoleon III had been the true sovereign of Rome, where he had many friends and relations.... Without him the temporal power would never have been reconstituted, nor, being reconstituted, would have endured."[5]

Dilemma

Pope Pius IX and succeeding popes Leo XIII, Pius X, Benedict XV, and Pius XI took great care not to recognize the legitimacy of the Italian government following the capture of Rome. Several options were considered, including giving the city a status similar to that of Moscow at the time (which, despite being the capital of Russia, was not the seat of government), but there was widespread agreement that Rome must be the capital to ensure the survival of the new state. However, Victor Emmanuel II of Italy refused to take residence in the Quirinal Palace, and foreign powers were likewise uneasy with the move. The British ambassador noted the apparent contradiction of a secular government sharing the city with a religious government, while the French foreign minister wrote:

If [Italy] would consent to view Florence as the seat of government, it would solve the Papal question. It would show great sense, and the political credit it would thereby garner, as well as the honor, would offer a considerable advantage...Rome, under royal rule—an integral part of the Italian nation, but remaining Holy or, better yet, the Dominant center of the domain of the faith—would lose none of its prestige and would redound to Italy's credit. And conciliation would then come about naturally, because the pope would become accustomed to seeing himself as living in his own home, not having a king around.

However, the government refused such suggestions and the king eventually took up residence in the Quirinal Palace. Regarded by Roman citizens as the ultimate sign of authority in the city, the Quirinal had been built and used by previous popes. When asked for the keys, Pius IX reportedly said, "Whom do these thieves think they are kidding asking for the keys to open the door? Let them knock it down if they like. Bonaparte's soldiers, when they wanted to seize Pius VI, came through the window, but even they did not have the effrontery to ask for the keys". A locksmith was later hired.[6]

Law of Papal Guarantees

Italy's Law of Guarantees, passed by the senate and chamber of the Italian parliament on 13 May 1871, accorded the Pope certain honors and privileges similar to those enjoyed by the King of Italy, including the right to send and receive ambassadors who would have full diplomatic immunity, just as if he still had temporal power as ruler of a state. The law was intended to attempt to avoid further antagonizing the pope following unification and was roundly criticized by anti-clerical politicians across the political spectrum, particularly on the left. At the same time, it subjected the papacy to a law that the Italian parliament could modify or abrogate at any time.

Pope Pius IX and his successors refused to recognize the right of the Italian king to reign over what had formerly been the Papal States, or the right of the Italian government to decide his prerogatives and make laws for him.[7] Asserting that the Holy See needed to maintain clearly manifested independence from any political power in its exercise of spiritual jurisdiction, and that the Pope should not appear to be merely a "chaplain of the King of Italy",[8] Pius IX rejected the Law of Papal Guarantees with its offer of an annual financial payment to the Pope.

Despite the Italian state's repeated assurances of the Pope's absolute liberty of movement within Italy and abroad, the popes refused to set foot outside the walls of the Vatican and thereby put themselves under the protection of the Italian forces of law and order, an implicit recognition of the changed situation. Consequently, the description "prisoners of the Vatican" was applied to them,[9] until the Lateran Treaty of 1929 settled the Roman Question by establishing Vatican City as an independent state.

During this time, Italian nobility who owed their titles to the Holy See rather than the Kingdom of Italy became known as the Black Nobility as they were considered to be in mourning.

Plans to leave Rome

Several times during his pontificate, Pius IX considered leaving Rome a second time. He had fled Rome in disguise in November 1848, following the assassination of his Minister of Finance, Count Pellegrino Rossi. One occurrence was in 1862, when Giuseppe Garibaldi was in Sicily gathering volunteers for a campaign to take Rome under the slogan Roma o Morte (Rome or Death). On 26 July 1862, before Garibaldi and his volunteers were stopped at Aspromonte,

Pius IX confided his fears to Lord Odo Russell, the British Minister in Rome, and asked whether he would be granted political asylum in England after the Italian troops had marched in. Odo Russell assured him that he would be granted asylum if the need arose, but said that he was sure that the Pope's fears were unfounded.[10]

Another instance and rumours of others occurred after the Capture of Rome and the suspension of the First Vatican Council. These were confided by Otto von Bismarck to Julius Hermann Moritz Busch:

As a matter of fact, he has already asked whether we could grant him asylum. I have no objection to it—Cologne or Fulda. It would be passing strange, but after all not so inexplicable, and it would be very useful to us to be recognised by Catholics as what we really are, that is to say, the sole power now existing that is capable of protecting the head of their Church. [...] But the King [later to become Wilhelm I, German Emperor] will not consent. He is terribly afraid. He thinks all Prussia would be perverted and he himself would be obliged to become a Catholic. I told him, however, that if the Pope begged for asylum he could not refuse it. He would have to grant it as ruler of ten million Catholic subjects who would desire to see the head of their Church protected.[11]

Rumours have already been circulated on various occasions to the effect that the Pope intends to leave Rome. According to the latest of these the Council, which was adjourned in the summer, will be reopened at another place, some persons mentioning Malta and others Trient. [...] Doubtless the main object of this gathering will be to elicit from the assembled fathers a strong declaration in favour of the necessity of the Temporal Power. Obviously a secondary object of this Parliament of Bishops, convoked away from Rome, would be to demonstrate to Europe that the Vatican does not enjoy the necessary liberty, although the Act of Guarantee proves that the Italian Government, in its desire for reconciliation and its readiness to meet the wishes of the Curia, has actually done everything that lies in its power.[12]

Lateran Treaty

The Lateran Treaty resolved the Roman Question in 1929; the Holy See acknowledged Italian sovereignty over the former Papal States and Italy recognized papal sovereignty over Vatican City. The Holy See limited its request for indemnity for the loss of the Papal States and of ecclesiastical property confiscated by the Italian State to much less than would have been due to it under the Law of Guarantees.[13]

Literature

Historical novels such as Fabiola and Quo Vadis have been interpreted as comparing the treatment of the popes by the newly formed Kingdom of Italy to the persecution of early Christians in the Roman Empire.[14]

See also

Notes

- Brendel, Otto (1942). Washington University Studies: New series, Language and literature. Washington University.

- Pyat, Félix (1849). Question romaine: affaire du 13 juin: lettre aux électeurs de la Seine, de la Nièvre et du Cher. Lausanne: Société éditrice l'Union. Retrieved 22 February 2015.

- "The Roman Question" in The Westminster Review, No. CXLI, July 1859, pp. 120–121

- De Cesare, 1909, p. 444.

- De Cesare, 1909, pp. 440–443.

- Kertzer 2004, pp. 79–83.

- "Law of Guarantees". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2007-02-18.

- Pollard, 2005, p. 11.

- Kertzer, David I. (2006-02-20). Prisoner of the Vatican: The Popes, the Kings, and Garibaldi's Rebels in the Struggle to Rule Modern Italy. HMH. ISBN 9780547347165.

- Jasper Ridley, Garibaldi, Viking Press, New York (1976) p. 535

- Moritz Busch, Bismarck: Some Secret Pages of His History, Vol. I, Macmillan (1898) p. 220, entry for 8 November 1870

- Moritz Busch, Bismarck: Some Secret Pages of His History, Vol. II, Macmillan (1898) pp. 43–44, entry for 3 March 1872

- "Text of the Lateran Treaty of 1929". www.aloha.net. Retrieved 2018-08-07.

- Pollard, 2005, p. 10.

References

- About, Edmond (1859). The Roman Question. London: W. Jeffs.

- De Cesare, Raffaele (1909). The Last Days of Papal Rome. London: Archibald Constable & Co. p. 449.

the last days of papal rome.

- Hebblethwaite, Peter (1987). Pope John XXIII: Shepherd of the Modern World. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-17298-2.

- Kertzer, David (2004). Prisoner of the Vatican. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-618-22442-4.

- Kertzer, David I. (2014). The Pope and Mussolini: The Secret History of Pius XI and the Rise of Fascism in Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198716167.

- Pollard, John F. (2005). Money and the Rise of the Modern Papacy: Financing the Vatican, 1850–1950. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81204-6.

- Russell, Odo William Leopold (1980). The Roman Question: Extracts from the Despatches of Odo Russell from Rome, 1858-1870. Wilmington DE USA: M. Glazier. ISBN 9780894531507. (reprint of 1962 ed.)

- Scott, Ivan (1969). The Roman Question and the Powers, 1848–1865. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands. ISBN 9789401575416.

.jpg.webp)