Rowther

Rowther or Ravuttar (Tamil: இராவுத்தர்-Irauttar) title used by Prominent Military Cavalry community from Southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu.[1] they are descendants of Turks have Turkish Ancestry.[2] Ravuttars are clan based Martial population like the Maravars,[3] Rawthers are an Endogomous group.[4] The Rawthers remember their Ancient heroic valour in the marriage ceremonies and bridegroom is conducted in the procession on a horse, but this process is fast disappearing.[5] they constitute the multi-ethnic Tamil Muslim, an Islamic community spread across South India and South East Asia. Rowthers follow Hanafi school of Fiqh.[6] Now they are Entrepreneurs, Business peoples and mostly landlords.

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Singapore, Malaysia, Middle east, UK & USA | |

| Languages | |

| Tamil | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Indo-Turkic people |

Etymology

Ravuttar(Ravutta) is derived from the Sanksrit Raja-putra, in the sense of the 'Prince', 'Nobleman' or 'Horseman'. D.C.Sircar points out that Ravutta or Rahutta, as a title, means as a Subordinate Ruler.[7]

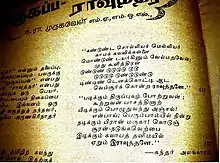

The etymology of the word 'Rowther' is meaning 'Brave Horseman'.[8] and some scholars claims that word come raja-putra (Prince) from Rathore (Muslim Rajputs). Sometimes spelt as Ravuthar/Rawther.They word Rowther might have originated from 'Ravoot', 'Raut' or 'Ravutta' which means 'king', 'Horseman', 'Nobleman', as they were Cavalry men in the army of a Chola king.[9] Rowthers is also known as 'Turukkiyar - துருக்கியர்' meaning Turks. 'Muttal Ravuttar' a Warlord with Ravuttar style dressed with sword in Draupathi temples. Ravuttars are Rulers,Cheftains and Cavalry force and they found as 15th to 18th-century southern Tamil poligers, zamindars and cheftains.[10]

Identity and origins

Chola kings, who dominated Tamil Nadu for over two centuries (approximately 950 AD to 1200 AD) waned, and Pandya kings had the upper hand for the next century (approximately 1200 AD to 1300 AD). King Maravarman Kulasekhara Pandyan (1268 - 1310) had two sons Jatavarman Sundara Pandyan and Jatavarman Veera Pandyan. The elder son, Sundara Pandyan, was by the king's wife and the younger, Veera Pandyan, was by a mistress. Contrary to tradition, the king proclaimed that the younger son would succeed him.This enraged Sundara Pandyan. He killed the father and became king in 1310. Some local chieftains in the kingdom swore allegiance to the younger brother Veera Pandian and a civil war broke out.

Sundara Pandyan was defeated and he fled the country. He sought help from the far off northern ruler Sultan Ala-ud-din Khilji, who was ruling much of northern India from Delhi. At that time, his army under General Malik Kafur was in the south at Dvarasamudra (far to the north of Tamil Nadu). Khilji agreed to help Sundara Pandyan and ordered Malik Kafur's army to march to Tamil Nadu. With Sundara Pandyan's assistance, this Muslim army from the north entered Tamil Nadu in 1311. Many historians believe that Malik Kafur, who was based in Dvarasamudra at that time, was not planning to march south all the way to Tamil Nadu, and that, but for Sundara Pandyan's request to Sultan Ala-ud-din Khilji, he would never have invaded Tamil Nadu. Thus the first invasion of Tamil Nadu from Delhi was a direct result of the internal quarrel in the Pandyan royal family.Once inside Tamil Nadu and his army well entrenched with not much opposition, Malik Kafur turned on Sundara Pandyan also, whom he came to help. The latter fled Madurai to southern Pandya Nadu. Sultan Ala-ud-din Khilji and Malik Kafur never intended to conquer and hold Tamil Nadu as part of the Delhi Sultanate; he did not occupy Tamil Nadu but turned back north. (Sundara Pandyan's uncle Vikrama Pandyan did win a couple of battles against Malik Kafur but many historians do not believe it to be the reason for Malik Kafur leaving Tamil Nadu.

Before invasion of Moghul, Chola King invited Turkish of the Seljuk Turks from Ottoman Empire from the Fractions of Hanafi school (Known as Rowther in South India) for Horse trade link in 1212 AD. A biggest armada of Turks traders and missionaries settled in Tharangambadi, Nagapattinam, Karaikal, Muthupet, Koothanallur and Podakkudi.[11] Turkish Rowthers were unable to convert Hindus in Tanjore regions since Hindus were very stubborn in their belief, so the Turkish mission and traders settled in this area's with their armada and expanded to a moderate size of Islam community. These new settlements were now added to the Rowther community. Hanafi franctions have a mix of fair and pale complexions because they were more closely connected with the Turkish than others in South, Rowther women wear Purdah same as Turks and Iranian compared to Marakkars ( sea traders) who just wear sarees. There are some Turkish Anatolian and Turkish Safavid Inscriptions found in wide area from Tanjore to Thiruvarur and in many villages. These inscriptions are seized by Madras Museum and are available for public viewing. Contact Archeologic Division at Madras Museum, for viewing and further research. Some Turkish inscriptions also stolen from Big Mosque of Koothanallur in 1850. And Last pandya kingdom great pandya kulashekara, the agent of the Horse trading Pandya Sultan Jamaludin (Horse Trader-Rowther),Governor of Shiraz, held the chief place in the region.he occupied, according to Muslim historians, a place even in the council of pandyas.[12]

There are two factions of Rowthers in Tamil Nadu, Sultan Ala-ud-din Khilji's (Moghul) clan descendants Turkish Sultans and their Rathore (Rajputs) warriors covers majority of Tamil Nadu while Seljuk Turkish clans remains in Tharangambadi (Nagapattinam), Karaikal, Muthupet, Koothanallur and Podakkudi. Both now Moghul and Turkish Hanafi expanded with Population and some circumstantial evidence in historical sources that the Rowther are part related to Maravar converts.[13] Ravuttars worked in the administration of the Vijayanagar Nayaks.[14]

Religious reconciliation code in Tamilnadu

The role of the Rowthers is very much in the religious harmony and social cohesion of Tamil Nadu[15]

The Tamil Muslim Ravuttars working in the administration of the Vijayanagar nayak somewhere In the Khurram kunda.The inscription details the dedication of the land by the Rowther Muslim to near a Murugan temple in cheyyur. The inscription not only reiterates the fact that Ravuttars (Rowthers) muslim in the part of the Vijayanagar administration, but also that their relationship went beyond religion, As can be seen by the donation to the temple.Much before the Tamil Muslim Ravuttars made the Contribution to the Murugan temple,

Arunagirinathar,the 15th Century Tamil poat,calls Lord Murugan as'Sur kondra Ravuttan' (the Ravuttan who vanquised the demon sur) in his kandar Alankaram and in kandar venba.[16]

Muttal Ravuttar

Muttal Ravuttar is that it is specifically as a Muslim that he figures as a kshatriya who"Protect the field" of the kindgom who ultimately Hindu ideal the Draupathi cult espouses with these consideration in mind, we may now look more closely at anomalous figure: First at the god himself and then myths, iconography,and rituals that define his relation to Draupathi and his role in her cult.

As we noted in chapter 3, The Muttal Ravuttar derives its Second element from a term meaning Muslim Rowther (Cavalier, Horseman,or trooper).the term comes from Urdu Raut, apparently via a prakit derivation from 'raja-putra' (Prince).[10]

References

- J. P. Mulliner. Rise of Islam in India. University of Leeds chpt. 9. Page re215

- People of India. Tamil Nadu. Singh, K. S., 1935–2006., Thirumalai, R., Manoharan, S., Anthropological Survey of India. Madras[17]

- Singh, Ashok Pratap. (2007). Psychological implications in industrial performance[4]

- People of India. India's communities. Singh, K. S., 1935-2006., Anthropological Survey of India. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press.[6]

- Sarandib: An Ethnology Muslims in srilanka Asiff Hussein[18]

- (J. B. Prashant) (1997): The political evolution of Muslims in Tamil Nadu and Madras, 1930-1947[1]

- Tschacher, Torsten. (2001). Islam in Tamilnadu : varia[13]

- Kerala. Singh, K. S., 1935-2006., Madhava Menon, T., Tyagi, D., 1943-, Kulirani, B. Francis., Anthropological Survey of India.[19]

- Mohan, Anupama. (2012). Utopia and the village in South Asian literatures[2]

- Bayly, Susan. (1989). Saints, goddesses, and kings : Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900[8]

- Madras, Chennai : a 400-year record of the first city of modern India Muthiah, S., 1930–2019., Association of British Scholars (India).[14]

- More, J. B. Prashant (1997). The political evolution of Muslims in Tamilnadu and Madras, 1930-1947. Hyderabad, India: Orient Longman. pp. 21–22. ISBN 81-250-1011-4. OCLC 37770527.

- Mohan, Anupama (2012). Utopia and the village in South Asian literatures. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 206. ISBN 978-0-230-35498-2. OCLC 785873604.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf. (1988-<1991>). The cult of Draupadī. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-226-34045-7. OCLC 16833684. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Singh, Ashok Pratap (2007). Psychological implications in industrial performance. Kumari, Patiraj, 1960- (1st ed.). New Delhi, India: Global Vision Pub. House. pp. 706–708. ISBN 81-8220-200-0. OCLC 295034951.

- Rājāmukamatu, Je (2005). Maritime History of the Coromandel Muslims: A Socio-historical Study on the Tamil Muslims 1750-1900. Director of Museums, Government Museum.

- Singh, K. S., ed. (1998). People of India: India's communities. New Delhi, India: Oxford University Press. pp. 3001–3002. ISBN 0-19-563354-7. OCLC 40849565.

- Rao, C. V. Ramachandra (1976). Administration and Society in Medieval Āndhra (A.D. 1038-1538) Under the Later Eastern Gaṅgas and the Sūryavaṁśa Gajapatis. Mānasa Publications. p. 88.

- Bayly, Susan (1989). Saints, goddesses, and kings : Muslims and Christians in South Indian Society, 1700-1900. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. p. 98. ISBN 0-521-37201-1. OCLC 70781802.

- Singh, K. S.; Madhava Menon, T.; Tyagi, D.; Kulirani, B. Francis (2002). Kerala. New Delhi: Affiliated East-West Press [for] Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1306. ISBN 81-85938-99-7. OCLC 50814919.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (1988–1991). The cult of Draupadī. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 13–14, 102. ISBN 0-226-34045-7. OCLC 16833684.

- Fragner, Bert G.; Kauz, Ralph; Ptak, Roderich; Schottenhammer, Angela. Pferde in Asien : Geschichte, Handel und Kultur [Horses in Asia : history, trade and culture]. Wien. pp. 150–160. ISBN 978-3-7001-6638-2. OCLC 1111579097.

- Arunachalam, S. (2011). The history of the pearl fishery of the Tamil coast. Pavai Publications. p. 96. ISBN 978-81-7735-656-4. OCLC 793080699.

- Tschacher, Torsten (2001). Islam in Tamilnadu : varia. Halle (Saale): Institut für Indologie und Südasienwissenschaften der Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg. p. 99. ISBN 3-86010-627-9. OCLC 50208020.

- Muthiah, S., ed. (2008). Madras, Chennai : a 400-year record of the first city of modern India (1st ed.). Chennai: Palaniappa Brothers. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8. OCLC 419265511.

- Anwar, Kombai S. (7 June 2018). "A secular temple in Kongu heartland". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 23 December 2020.

- Muthiah, S. (2008). Madras, Chennai : a 400-year record of the first city of modern India (1st ed.). Chennai: Palaniappa Brothers. p. 140. ISBN 978-81-8379-468-8. OCLC 419265511.

- Singh, K. S.; Thirumalai, R.; Manoharan, S., eds. (1997). People of India. Tamil Nadu. Madras: Affiliated East-West Press [for] Anthropological Survey of India. pp. 1259–1262. ISBN 81-85938-88-1. OCLC 48502905.

- Hussein, Asiff (2007). Sarandib : an ethnological study of the Muslims of Sri Lanka (1st ed.). Nugegoda: Asiff Hussein. ISBN 955-97262-2-6. OCLC 132681713.

- Singh, K. S.; Madhava Menon, T.; Tyagi, D.; Kulirani, B. Francis, eds. (2002). Kerala. New Delhi: Affiliated East-West Press [for] Anthropological Survey of India. p. 1306. ISBN 81-85938-99-7. OCLC 50814919.