Salome (opera)

Salome, Op. 54, is an opera in one act by Richard Strauss. The libretto is Hedwig Lachmann's German translation of the 1891 French play Salomé by Oscar Wilde, edited by the composer. Strauss dedicated the opera to his friend Sir Edgar Speyer.[1]

| Salome | |

|---|---|

| Opera by Richard Strauss | |

1910 poster by Ludwig Hohlwein | |

| Librettist | Oscar Wilde (Hedwig Lachmann's German translation of the French play Salomé, edited by Richard Strauss) |

| Language | German |

| Premiere | |

The opera is famous (at the time of its premiere, infamous) for its "Dance of the Seven Veils". The final scene is frequently heard as a concert-piece for dramatic sopranos.

Composition history

Oscar Wilde originally wrote his Salomé in French. Strauss saw the play in Lachmann's version and immediately set to work on an opera. The play's formal structure was well-suited to musical adaptation. Wilde himself described Salomé as containing "refrains whose recurring motifs make it so like a piece of music and bind it together as a ballad".[2]

Strauss composed the opera to a German libretto, and that is the version that has become widely known. In 1907, Strauss made an alternate version in French (the language of the original Oscar Wilde play), which was used by Mary Garden, the world's most famous proponent of the role, when she sang the opera in New York, Chicago, Milwaukee, Paris, and other cities. Marjorie Lawrence sang the role both in French (for Paris) and in German (for the Metropolitan Opera, New York) in the 1930s. The French version is much less well known today, although it was revived in Lyon in 1990,[3] and recorded by Kent Nagano with Karen Huffstodt in the title role and José van Dam as Jochanaan.[4] In 2011, the French version was staged by Opéra Royal de Wallonie in Liège, starring June Anderson.

Performance history

The combination of the Christian biblical theme, the erotic and the murderous, which so attracted Wilde to the tale, shocked opera audiences from its first appearance. Some of the original performers were very reluctant to handle the material as written and the Salome, Marie Wittich, "refused to perform the 'Dance of the Seven Veils'", thus creating a situation where a dancer stood in for her.[3] This precedent has been largely followed, one early notable exception being that of Aino Ackté, whom Strauss himself dubbed "the one and only Salome".[5]

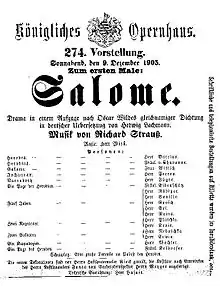

Salome was first performed at the Königliches Opernhaus in Dresden on 9 December 1905, and within two years, it had been given in 50 other opera houses.[3]

Gustav Mahler could not gain the consent of the Vienna censor to have it performed; therefore it was not given at the Vienna State Opera until 1918. The Austrian premiere was given at the Graz Opera in 1906 under the composer, with Arnold Schoenberg, Giacomo Puccini, Alban Berg, and Gustav Mahler in the audience.

Salome was banned in London by the Lord Chamberlain's office until 1907. When it was given its premiere performance at Covent Garden in London under Thomas Beecham on 8 December 1910,[3] it was modified, much to Beecham's annoyance and later amusement.

The United States premiere took place at a special performance by the Metropolitan Opera with Olive Fremstad in the title role with the dance performed by Bianca Froehlich on 22 January 1907.[6][7] The mixed reviews were summarized "that musicians were impressed by the power displayed by the composer" but "the story is repugnant to Anglo-Saxon minds."[8] Afterwards, under pressure from wealthy patrons, "further performances were cancelled"[3] and it was not performed there again until 1934.[6] These patrons entreated the visiting Edward Elgar to lead the objections to the work, but he refused point-blank, stating that Strauss was "the greatest genius of the age".[9]

In 1930, Strauss took part in a festival of his music at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, and conducted Salome on 5 November in a version with a slightly reduced orchestration (dictated by the size of the pit).

Today, Salome is a well-established part of the operatic repertoire; there are numerous recordings. It has a typical duration of 100 minutes.[10]

Roles

| Role | Voice type | Premiere cast, 9 December 1905[11] Conductor: Ernst von Schuch |

|---|---|---|

| Herodes, Tetrarch of Judaea and Perea | tenor | Karel Burian |

| Herodias, his wife (and sister-in-law) | mezzo-soprano | Irene von Chavanne |

| Salome, his stepdaughter (and niece) | soprano | Marie Wittich |

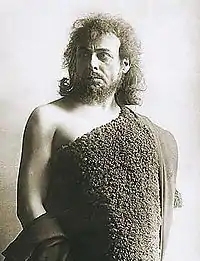

| Jochanaan (John the Baptist) | baritone | Karl Perron |

| Narraboth, Captain of the Guard | tenor | Rudolf Ferdinand Jäger |

| The Page of Herodias | contralto | Riza Eibenschütz |

| First Jew | tenor | Hans Rüdiger |

| Second Jew | tenor | Hans Saville |

| Third Jew | tenor | Georg Grosch |

| Fourth Jew | tenor | Anton Erl |

| Fifth Jew | bass | Leon Rains |

| First Nazarene | bass | Friedrich Plaschke |

| Second Nazarene | tenor | Theodor Kruis |

| First soldier | bass | Franz Nebuschka |

| Second soldier | bass | Hans Erwin (Hans Erwin Hey) |

| A Cappadocian | bass | Ernst Wachter |

| A slave | soprano/tenor | Maria Keldorfer |

| Royal guests (Egyptians and Romans), and entourage, servants, soldiers (all silent) | ||

Synopsis

A great terrace in the Palace of Herod, set above the banqueting hall. Some soldiers are leaning over the balcony. To the right there is a gigantic staircase, to the left, at the back, an old cistern surrounded by a wall of green bronze. The moon is shining very brightly.

Narraboth gazes from a terrace in Herod's palace into the banquet hall at the beautiful Princess Salome; he is in love with her, and apotheosizes her, much to the disgusted fearfulness of the Page of Herodias. The voice of the Prophet Jochanaan is heard from his prison in the palace cistern; Herod fears him and has ordered that no one should contact him, including Jerusalem's High Priest.

Tired of the feast and its guests, Salome flees to the terrace. When she hears Jochanaan cursing her mother (Herodias), Salome's curiosity is piqued. The palace guards will not honor her petulant orders to fetch Jochanaan for her, so she teasingly works on Narraboth to bring Jochanaan before her. Despite the orders he has received from Herod, Narraboth finally gives in after she promises to smile at him.

Jochanaan emerges from the cistern and shouts prophecies regarding Herod and Herodias that no one understands, except Salome when the Prophet refers to her mother. Upon seeing Jochanaan, Salome is filled with an overwhelming desire for him, praising his white skin and asking to touch it, but he rejects her. She then praises his black hair, again asking to touch it, but is rejected once more. She finally begs for a kiss from Jochanaan's lips, and Narraboth, who cannot bear to hear this, kills himself. As Jochanaan is returned to the well, he preaches salvation through the Messiah.

Herod enters, followed by his wife and court. He slips in Narraboth's blood and starts hallucinating. He hears the beating of wings. Despite Herodias' objections, Herod stares lustfully at Salome, who rejects him. Jochanaan harasses Herodias from the well, calling her incestuous marriage to Herod sinful. She demands that Herod silence him. Herod refuses, and she mocks his fear. Five Jews argue concerning the nature of God. Two Nazarenes tell of Christ's miracles; at one point they bring up the raising of Jairus' daughter from the dead, which Herod finds frightening.

Herod asks for Salome to eat with him, drink with him; indolently, she twice refuses, saying she is not hungry or thirsty. Herod then begs Salome to dance for him, Tanz für mich, Salome, though her mother objects. He promises to reward her with her heart's desire – even if it were one half of his kingdom.

After Salome inquires into his promise, and he swears to honor it, she prepares for the "Dance of the Seven Veils". This dance, very oriental in orchestration, has her slowly removing her seven veils, until she lies naked at his feet. Salome then demands the head of the prophet on a silver platter. Her mother cackles in pleasure. Herod tries to dissuade her with offers of jewels, peacocks, and the sacred veil of the Temple. Salome remains firm in her demand for Jochanaan's head, forcing Herod to accede to her demands. After a desperate monologue by Salome, an executioner emerges from the well and delivers the severed head as she requested.

Salome now declares her love for the severed head, caressing it and kissing the prophet's dead lips passionately. Horrified, Herod orders his soldiers, "Kill that woman!" They rush forward and crush Salome under their shields.

Instrumentation

Strauss scored Salome for the following large orchestra:

- Woodwinds: piccolo, 3 flutes, 2 oboes, English horn, heckelphone, E-flat clarinet, 2 clarinets in B-flat, 2 clarinets in A, bass clarinet, 3 bassoons, contrabassoon

- Brass: 6 horns in F, 4 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba

- Percussion (8–9 players): 5 timpani, snare drum, bass drum, cymbals, triangle, tam-tam, tambourine, castanets, glockenspiel, xylophone

- Keyboards: celesta, harmonium (offstage), organ (offstage)

- Strings: 2 harps, 16 violins I, 16 violins II, 10–12 violas, 10 violoncellos, 8 double basses

The instrumentation contains several notes for strings and woodwinds that are unplayable because they are too low; Strauss was aware of this.[13]

Music

The music of Salome includes a system of leitmotifs, or short melodies with symbolic meanings. Some are clearly associated with people such as Salome and Jochanaan (John the Baptist). Others are more abstract in meaning.[14] Strauss's use of leitmotifs is complex, with both symbolism and musical form subject to ambiguity and transformation. Some leitmotifs, especially those associated with Herod, change frequently in form and symbolic meaning, making it futile to pin them down to a specific meaning.[14] Strauss provided names for some of the leitmotifs, but not consistently, and other people have assigned a variety of names. These names often illustrate the ambiguity of certain leitmotifs. For example, Gilman's labels tend to be abstract (such as "Yearning", "Anger", and "Fear"),[15] while Otto Roese's are more concrete (he called Gilman's "Fear" leitmotif "Herod's Scale"). Regarding the important leitmotif associated with Jochanaan, which has two parts, Gilman called the first part "Jochanaan" and the second part "Prophecy", while Roese labels them the other way around. Labels for the leitmotifs are common, but there is no final authority. Derrick Puffett cautions against reading too much into any such labels.[14] In addition to the leitmotifs, there are many symbolic uses of musical color in the opera's music. For example, a tambourine sounds every time a reference to Salome's dance is made.[14]

The harmony of Salome makes use of extended tonality, chromaticism, a wide range of keys, unusual modulations, tonal ambiguity, and polytonality. Some of the major characters have keys associated with them, such as Salome and Jochanaan, as do some of the major psychological themes, such as desire and death.

Strauss edited the opera's libretto, in the process cutting almost half of Wilde's play, stripping it down and emphasizing its basic dramatic structure. The structural form of the libretto is highly patterned, notably in the use of symmetry and the hierarchical grouping of events, passages, and sections in threes. Examples of three-part structure include Salome's attempt to seduce Narraboth, in order to get him to let her see Jochanaan. She tries to seduce him three times, and he capitulates on the third. When Jochanaan is brought before Salome he issues three prophecies, after which Salome professes love for Jochanaan three times—love of his skin, his hair, and his lips, the last of which results in Jochanaan cursing her. In the following scene Herod three times asks Salome to be with him—to drink, eat, and sit with him. She refuses each time. Later Herod asks her to dance for him, again three times. Twice she refuses, but the third time Herod swears to give her whatever she wants in return and she accepts. After she dances and says she wants Jochanaan's head on a platter, Herod, not wanting to execute the Prophet, makes three offers—an emerald, peacocks, and finally, desperately, the Veil of the Sanctuary of the Holy of Holies. Salome rejects all three offers, each time more stridently insisting on Jochanaan's head. Three-part groupings occur elsewhere on both larger and smaller levels.[2]

In the final scene of the opera, after Salome kisses Jochanaan's severed head, the music builds to a dramatic climax, which ends with a cadence involving a very dissonant unorthodox chord one measure before rehearsal 361. This single chord has been widely commented on. It has been called "the most sickening chord in all opera", an "epoch-making dissonance with which Strauss takes Salome...to the depth of degradation", and "the quintessence of Decadence: here is ecstasy falling in upon itself, crumbling into the abyss".[16] The chord is often described as polytonal, with a low A7 (a dominant seventh chord) merged with a higher F-sharp major chord. It forms part of a cadence in the key of C-sharp major and is approached and resolved from C–sharp major chords. Not only is the chord shockingly dissonant, especially in its musical context and rich orchestration, it has broader significance due in part to Strauss's careful use of keys and leitmotifs to symbolize the opera's characters, emotions such as desire, lust, revulsion, and horror, as well as doom and death. A great deal has been written about this single chord and its function within the large-scale formal structure of the entire opera.[17]

The role of Salome

The vocal demands of the title-role are the same as those of an Isolde, Brünnhilde, or Turandot, in that, ideally, the role requires the volume, stamina, and power of a true dramatic soprano. The common theme of these four roles is the difficulty in casting an ideal soprano who has a truly dramatic voice as well as being able to register as a young woman.

Nevertheless, Maria Cebotari, Ljuba Welitsch, Birgit Nilsson, Leonie Rysanek, Éva Marton, Radmila Bakočević, Montserrat Caballé, Anja Silja, Phyllis Curtin, Karan Armstrong, Nancy Shade, Dame Gwyneth Jones, Catherine Malfitano, Hildegard Behrens, Maria Ewing, Teresa Stratas (only in a film version, not on stage), Olive Fremstad, Brenda Lewis, and Karita Mattila are among the most memorable who have tackled the role in the last half-century. Each of these singers has brought her own interpretation to the title character. Perhaps the two most famous recordings of the opera are Herbert von Karajan's EMI recording with Hildegard Behrens and Sir Georg Solti's Decca recording with Birgit Nilsson as Salome.

In addition to the vocal and physical demands, the role also calls for the agility and gracefulness of a prima ballerina when performing the opera's famous "Dance of the Seven Veils". Finding one individual with all of these qualities is extremely daunting. Due to the complexity of the role's demands, some of its performers have had a purely vocal focus by opting to leave the dancing to stand-ins who are professional dancers. Others have opted to combine the two and perform the dance themselves, which is closer to Strauss's intentions. In either case, at the end of the "Dance of the Seven Veils", some sopranos (or their stand-ins) wear a body stocking under the veils, while others (notably Malfitano, Mattila and Ewing) have appeared nude at the conclusion of the dance.

As for the required vocal range of the title role, it is an extraordinary case: The highest note is the high B5, not irregular for a soprano or mezzo-soprano to sing, while the lowest note is a low G♭3, in the contralto range and officially below the standard range for a mezzo-soprano. Considering this range, which is similar to many mezzo roles (such as Carmen and Amneris), one might assume that a high soprano is not essential to the piece, but it is; most of the relatively low sopranos who attempted this role found themselves straining their voices throughout the opera, and having reached the closing scene (the most important part of the opera for the title role) were very fatigued. This role is the classic example of the difference between tessitura and absolute vocal range: While mezzos can perform a high note (like Carmen), or even temporarily sustain a high tessitura, it is impossible for a singer to spend such a long time (with the needed strength and breath-control) in the second octave above the middle C unless she is a high soprano. Moreover, the low G♭ occurs twice in the opera, and in both cases it is in pianissimo—more of a theatrical effect than music—and can be growled instead of sung. The other low notes required are no lower than low A♮, and they are also quiet.

Transcriptions

The English composer Kaikhosru Shapurji Sorabji wrote in 1947 a piano transcription of the closing scene of the opera, entitled "Schluß-Szene aus Salome von Richard Strauss—Konzertmäßige Übertragung für Klavier zu zwei Händen" ("Final Scene from Salome by Richard Strauss – Concert Transcription arranged for Piano, two hands").

Recordings

See also

References

- "Salome". Boosey & Hawkes. Retrieved 6 June 2018.

Dedication: Meinem Freunde Sir Edgar Speyer

- Carpenter, Tethys (1989). "6. Tonal and dramatic structure". In Derrick Puffett (ed.). Richard Strauss, Salome. Cambridge University Press. pp. 92–93. ISBN 978-0-521-35970-2.

- Kennedy 2001, p. 889

- "Salome discography – Nagano 1991". operadis-opera-discography.org.uk.

- Charles Reid, Thomas Beecham: An Independent Biography, 1961, p. 103

- "Salome (1) Metropolitan Opera House: 01/22/1907". archives.metoperafamily.org. Metropolitan Opera. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Interpreters by Carl Van Vechten.

- "Comments on Events: Salome in New York". Musical News. 32 (836): 229–230. 9 March 1907. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- Liner notes to the recording of Salome with Birgit Nilsson and the Vienna Philharmonic under Georg Solti. Decca Records, 19XX

- "Salome – work details". Boosey & Hawkes.

- Casaglia, Gherardo (2005)."Salome, 9 December 1905". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- Cornell University College of Arts & Sciences News Letter

- Claudia Heine; Salome Reiser (2019). "Introduction" (PDF). Salome (critical ed.). Schott Music. p. XXIII. ISBN 978-3-7957-0980-8.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Carpenter, Tethys; Ayrey, Craig; et al. (1989). Derrick Puffett (ed.). Richard Strauss, Salome. Cambridge University Press. pp. 63, 68–69, 82. ISBN 978-0-521-35970-2.

- Gilman 1907, p. .

- Ayrey, Craig (1989). "7. Salome's final monologue". In Derrick Puffett (ed.). Richard Strauss, Salome. Cambridge University Press. pp. 123–130. ISBN 978-0-521-35970-2.

- See Puffett (1989), chapters 6 and 7.

Sources

- Gilman, Lawrence (1907). Strauss' Salome: A Guide to the Opera, with Musical Illustrations. J. Lane.

- Kennedy, Michael (2001). Holden, Amanda (ed.). The New Penguin Opera Guide. New York: Penguin Putnam. ISBN 0-14-029312-4.

Further reading

- Del Mar, Norman (1962). Richard Strauss. London: Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 0-214-15735-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salome (opera). |

- Salome, German libretto

- German libretto

- Documentation of libretto versions, Schott Music 2019 critical edition

- Salome: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project