Southwest Chief

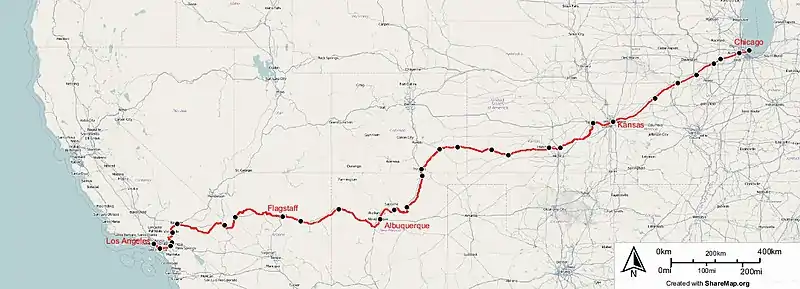

The Southwest Chief (formerly the Southwest Limited and Super Chief) is a passenger train operated by Amtrak on a 2,265-mile (3,645 km) route through the Midwestern and Southwestern United States. It runs between Chicago, Illinois and Los Angeles, California, passing through Illinois, Iowa, Missouri, Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona and California. Amtrak bills the route as one of its most scenic, with views of the Painted Desert and the Red Cliffs of Sedona, as well as the plains of Iowa, Kansas and Colorado. According to Amtrak, it affords views that are not possible while traveling along interstate highways.

The Southwest Chief at Los Cerrillos, New Mexico in 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Overview | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Service type | Long-distance higher speed rail | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Locale | Midwestern and Southwestern United States | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Super Chief, El Capitan | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| First service | March 7, 1974 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current operator(s) | Amtrak | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ridership | 1,006 daily – 367,267 annual (FY15)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Route | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Start | Chicago, Illinois | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Stops | 31 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| End | Los Angeles, California | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Distance travelled | 2,265 mi (3,645 km) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Average journey time | 43 hours, 15 minutes | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service frequency | 3 round trips weekly | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Train number(s) | 3 westbound, 4 eastbound | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| On-board services | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Class(es) | Coach, sleeper | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sleeping arrangements | 2-bed roomettes 2–4 bed bedrooms | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Catering facilities | Dining car, café | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Observation facilities | Lounge car | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Baggage facilities | Checked baggage (select stations) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Technical | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rolling stock | P42 locomotives Superliner cars | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Operating speed | 90 mph (145 km/h) maximum 55 mph (89 km/h) average (including stops) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Track owner(s) | BNSF Railway | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

During fiscal year 2019, the Southwest Chief carried 338,180 passengers, an increase of 2.1 percent from FY 2018.[2] The route grossed $43,184,176 in revenue during FY 2018, a 3.8 percent decrease from FY 2017.[3] Amtrak had plans for replacing the route between Albuquerque, New Mexico and Dodge City, Kansas with bus service, but as of October 2018, these are shelved.

History

The Southwest Chief is the successor to the Super Chief, inaugurated in 1936 as the flagship train of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. For most of its existence, it was "all-Pullman," carrying sleeping cars only. The Santa Fe merged the Super Chief with its all-coach counterpart, the El Capitan, in 1958. The merged train was known as the Super Chief/El Capitan, but retained the train numbers used by the Super Chief, 17 westbound and 18 eastbound.

Amtrak retained the Super Chief/El Capitan after taking over passenger rail service in 1971. During the summer of 1972, it was complimented by the Chief, reviving the name of another notable Chicago-Los Angeles sleeper operated by the Santa Fe. Amtrak dropped the El Capitan half in 1973. Then in March 1974, the Santa Fe forced Amtrak to discontinue using the Chief brand on its former trains because of a perceived decline in quality after the Amtrak takeover. The train was renamed the Southwest Limited that March 7. After subsequent improvements, the Santa Fe allowed Amtrak to change its name to the Southwest Chief on October 28, 1984.

National Chief

Amtrak operated the Southwest Chief in conjunction with the Capitol Limited, a daily Washington-Chicago service, in 1997 and 1998. The two trains used the same Superliner equipment sets, and passengers traveling on both trains could remain aboard during the layover in Chicago. Originally announced in 1996, Amtrak planned to call this through service the "National Chief" with its own numbers (15/16), although the name and numbers were never used. Amtrak dropped the practice with the May 1998 timetable.[4][5][6]

Accidents and incidents

- On October 2, 1979, the Southwest Limited derailed at Lawrence, Kansas. Of the 30 crew and 147 passengers on board, two people were killed and 69 were injured. The cause was excessive speed on a curve. Underlying causes were that the engineer was unfamiliar with the route, and that signage indicating the speed restriction had been removed during track repairs.[7]

- On August 9, 1997, the eastbound Southwest Chief derailed about 5 miles northeast of Kingman, Arizona, when a bridge, its undergirding washed out by a flash flood, collapsed under the weight of the train, which was traveling close to 90 miles per hour. While the lead locomotive stayed on the track, the three trailing locomotives, nine passenger cars, and seven baggage and mail cars derailed. All stayed upright. Of the 325 passengers and crew aboard, 154 people were injured and none were killed.[8]

- On October 16, 1999, the westbound Southwest Chief suffered a minor derailment near Ludlow, California, following the Hector Mine earthquake. All the cars stayed upright, and four passengers were injured.[9]

- On March 14, 2016, the Southwest Chief derailed 3 miles (4.8 km) from Cimarron, Kansas. Of 14 crew and 128 passengers, 20 were injured. Investigators determined the train derailed after the tracks were knocked out of alignment by a runaway truck from a nearby farm operation. The vehicle had rolled down a hill and struck the tracks after the owners had failed to secure the parking brake.[10][11]

Operations

Unique among all long-distance Superliner trains, the Southwest Chief is permitted to run up to a maximum of 90 mph (145 km/h) along significant portions of the route because of automatic train stop installed by the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. Given Amtrak's projected 41-hour travel time,[12] the average speed is in excess of 55 mph (89 km/h), including stops.

During the spring and summer, Volunteer Rangers with the Trails and Rails program from the National Park Service travel on board and provide a narrative between La Junta, Colorado, and Albuquerque, New Mexico. Starting in May 2013, Volunteer Rangers with Trails and Rails will also be on board, providing a narrative between Chicago and La Plata, Missouri.

From June through August, the Southwest Chief is used by Boy Scouts traveling to and from Philmont Scout Ranch via the Raton station. During those months, Raton station is staffed by Amtrak employees and handles checked baggage.

This route was one of five studied for possible performance improvements by Amtrak in FY 2012.[13]

Kansas downgrade

No BNSF freight service is offered between La Junta, Colorado and Lamy, New Mexico, and the railroad informed Amtrak that all maintenance costs are to be paid by the passenger carrier if it wished to continue to use the route.[14] BNSF also declared it will maintain trackage between Hutchinson, Kansas, and La Junta, at a Class III (60 mph passenger train maximum) speed instead of Class IV (79 mph passenger train maximum).

BNSF offered to host the Southwest Chief over its Southern Transcon via Wichita and Wellington, Kansas, Amarillo, Texas, and Clovis, New Mexico, once used by the San Francisco Chief. Amtrak sought help from the states involved to retain existing service on the train's historic route.[15] The states of Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico have since contributed money toward rebuilding the tracks and keeping the Chief on its current routing. Much of the funding for the rehabilitation projects has come from federal transportation grants.

In 2018, the Southwest Chief became the focal point of a struggle to determine whether to continue Amtrak as a national network or to operate regional stand-alone networks.[16]

The issue was provoked by Amtrak introducing new requirements for the third renewal grant and raising previously undiscussed technical issues regarding the midsection of the route.[17] A letter dated May 31, 2018, co-signed by 11 Senators condemned the action and urged providing the match.[18] Former Amtrak President and CEO Joseph H. Boardman in an open letter stated, "The Southwest Chief issue is the battleground whose outcome will determine the fate of American’s national interconnected rail passenger network."[16]

In June, Amtrak announced that it was considering the replacement of rail service along the Kansas portion of the Southwest Chief with Amtrak Thruway Motorcoach buses between Albuquerque and Dodge City, where train service east to Chicago would resume.[19] Senators in the affected area succeed in offering an amendment to a funding bill. Per a press release from the office of co-sponsor Senator Jerry Moran, "This amendment would provide resources for maintenance and safety improvements along the Southwest Chief route and would compel Amtrak to fulfill its promise of matching funding for the successful TIGER IX discretionary grant ... In addition, this amendment would effectively reverse Amtrak’s decision to substitute rail service with bus service over large segments of the route through FY2019."[20]

Composition

| August 23, 2019 | |

|---|---|

| Location | Raton, New Mexico |

| Train | 4 |

| |

A fourth Superliner coach may be added during peak travel periods. Usually a fourth coach is added and then removed in Kansas City, MO due to extra demand. The high-speeds along the BNSF Marceline Subdivision allow for considerable travel times from Kansas City to Chicago. Sometimes, private cars or deadhead cars can be seen riding along, also. http://on-track-on-line.com/amtkrinf-suprname.shtml

Route changes

Until 1979, the train traversed a different route from Kansas City to Emporia. That year, it was rerouted via Topeka, Kansas, to replace Amtrak service lost with the discontinuance of the Texas Chief. The reroute allowed Amtrak to maintain service to the Kansas state capital of Topeka and to Lawrence, home of the University of Kansas.

Prior to 1996, the Southwest Chief operated between Chicago and Galesburg, Illinois, via Joliet, Streator, and Chillicothe on the ATSF's Chillicothe Subdivision. Following the merger of the Burlington Northern and the Santa Fe in 1996, BNSF constructed a connector track at Cameron, Illinois, allowing for freight and passenger trains to connect from the BN Mendota Subdivision to the Chillicothe Subdivision.[21] The Chief was rerouted on the old Burlington Northern through Naperville, Princeton, and Mendota to Galesburg, a route shared with the California Zephyr, Illinois Zephyr, and Carl Sandburg.

In January 1994, the Southwest Chief was rerouted between San Bernardino and Los Angeles onto the Santa Fe Third District via Fullerton and Riverside. Previously, it served Pasadena and Pomona via the Santa Fe Pasadena subdivision, until that route was closed to all through traffic following the damage to a bridge over the eastbound lanes of Interstate 210 in Arcadia during the Northridge Earthquake. This resulted from ATSF selling that segment to the Los Angeles Metro for use as a light rail corridor. The Los Angeles Metro L Line now uses that stretch of right-of-way. A section of the track still exists, although it terminates in Irwindale adjacent to Interstate 210.

There were plans to add service to Pueblo and connecting with the proposed Front Range regional rail service between Denver and Pueblo. It would have also run along former Colorado & Southern tracks through Walsenburg, reconnecting with its current alignment at Trinidad. A more recent plan is to run a section of the train to Colorado Springs, Colorado via Pueblo.[22]

Ridership

| Ridership | Change over previous year | Ticket Revenue | Change over previous year | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007[23] | 316,668 | - | $37,935,113 | - |

| 2008[23] | 331,143 | $41,079,865 | ||

| 2009[23] | 318,025 | $38,033,503 | ||

| 2010[24] | 342,403 | $41,604,705 | ||

| 2011[24] | 354,912 | $44,184,060 | ||

| 2012[25] | 355,316 | $44,183,540 | ||

| 2013[25] | 355,815 | $45,129,813 | ||

| 2014[26] | 352,162 | $44,631,296 | ||

| 2015[26] | 367,267 | $44,904,314 | ||

| 2016[27] | 364,748 | $43,184,176 | ||

| 2017[28] | 363,000 | - | - | |

| 2018[29] | 331,239 | - | - | |

| 2019[29] | 338,180 | - | - | |

References

- "Amtrak FY15 Ridership & Revenue" (PDF). Amtrak. November 5, 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved November 30, 2016.

- https://media.amtrak.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/FY19-Year-End-Ridership

- http://media.amtrak.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/10/Amtrak-FY16-Ridership-and-Revenue-Fact-Sheet-4_17_17-mm-edits.pdf

- "Amtrak National Timetable". Timetables.org. November 10, 1996. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- "Amtrak National Timetable". Timetables.org. May 11, 1997. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- "Amtrak National Timetable". Timetables.org. May 17, 1998. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- "Derailment of Amtrak train No. 4 The Southwest Limited on the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway Company Lawrence, Kansas October 2, 1979" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. April 29, 1980. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 17, 2017. Retrieved March 15, 2016.

- Riccardi, Nicholas; Gorman, Tom (August 10, 1997). "Train From L.A. Derails in Arizona; 154 Injured". Los Angeles Times. ISSN 0458-3035. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016. Retrieved November 22, 2016.

- Dvorak, John (February 4, 2014). Earthquake Storms: An Unauthorized Biography of the San Andreas Fault. New York: Open Road Media. p. 264. ISBN 9781480447868. Archived from the original on November 22, 2016.

- "Amtrak train derails in Kansas". BBC News Online. Archived from the original on March 15, 2016. Retrieved March 14, 2016.

- ""Amtrak train derails near Cimarron". Dodge City Daily Globe. March 14, 2016. Archived from the original on June 3, 2018.

- "Southwest Chief Schedule" (PDF). Amtrak. May 30, 2018. Retrieved June 3, 2018.

- "PRIIA Section 210 FY12 Performance Improvement Plan" (PDF). Amtrak. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 19, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- Zimmermann, Karl (September 2, 2019). "Amtrak's Southwest Chief lives to ride the rails another day". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 3, 2019.

- Fred W. Frailey, "Minus its backbone, Amtrak makes a tempting target," Trains, August 2010, 18.

- Joseph A. Boardman, "Where is the public input? Where is the transparency?" Railway Age, May 10, 2018.

- Jim Souby, "Amtrak gets big boost from Congress, grant from DOT, reviews long-distance trains," ColoRail Passenger, Issue 84, 2018, 5.

- "We write to express our deep concern... "

- Ben Kuebrich, "Amtrak May End Passenger Rail Service In West Kansas. Moran: 'Amtrak Is Not Doing Its Job'", KCUR

- Senate Approves Moran, Udall Amendment to Maintain Southwest Chief Train Services Senator Jerry Moran official website Aug. 1, 2018

- "Galesburg to Streator". Donwinter.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved July 7, 2016.

- "Senators land $225k to study adding Amtrak spur in Colorado Springs". KOAA News 5 Southern Colorado. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- "Amtrak Fiscal Year 2009, Oct. 2008-Sept. 2009" (PDF). Trains Magazine.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on November 8, 2012. Retrieved July 30, 2012.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "AMTRAK SETS RIDERSHIP RECORD AND MOVES THE NATION'S ECONOMY FORWARD" (PDF).

- "Amtrak FY15 Ridership & Revenue" (PDF).

- "Amtrak FY16 Ridership & Revenue" (PDF). Amtrak. April 17, 2017.

- "Amtrak FY17 Ridership" (PDF).

- "Amtrak FY19 Ridership" (PDF).