Teyujagua

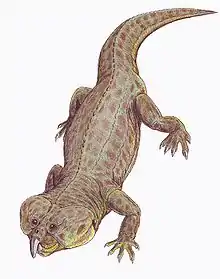

Teyujagua (named for Teyú Yaguá, a legendary beast from local Guaraní mythology) is an extinct genus of small, probably semi-aquatic archosauromorph reptile that lived in Brazil during the Early Triassic period. The genus contains the type and only known species, T. paradoxa. It is known from a well-preserved skull, and probably resembled a crocodile in appearance. It was an intermediary between the primitive archosauromorphs and the more advanced Archosauriformes, revealing the mosaic evolution of how the key features of the archosauriform skull were acquired. Teyujagua also provides additional support for a two-phase model of archosauriform radiation, with an initial diversification in the Permian followed by a second adaptive radiation in the Early Triassic.[1]

| Teyujagua | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skull in side view and dorsal view | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Neodiapsida |

| Clade: | Sauria |

| Clade: | Archosauromorpha |

| Clade: | Crocopoda |

| Genus: | †Teyujagua Pinheiro et al., 2016 |

| Type species | |

| †Teyujagua paradoxa Pinheiro et al., 2016 | |

Description

Teyujagua is known only from a well preserved skull with four associated cervical vertebrae, the only known postcranial material,[1] but it is inferred to have been a small, carnivorous quadruped that grew to a length of up to 1.5 metres (4.9 ft).[2]

Skull

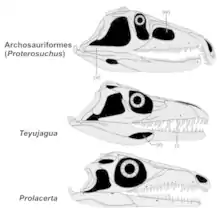

The skull of Teyujagua is exceptionally well preserved and almost complete, possessing several key features of the archosauriform skull. In total it measures approximately 115 millimetres (4.5 in), with a long, broad and flattened snout. Teyujagua possesses a mosaic of characteristics intermediate between basal archosauromorphs and Archosauriformes. Primitive features include the absence of an antorbital fenestra and an open lower temporal bar, however like Archosauriformes it has serrated teeth and an exposed mandibular fenestra on the lower jaw, features previously only found in Archosauriformes.[1]

The external nares are dorsally positioned and fused into a single large opening (confluent), a feature found in several aquatic and semi-aquatic Archosauriformes, although the orbits are positioned laterally and slightly forwards, providing limited binocular vision. The nasals are long and occupy much of the skull length, followed by short, broad frontals that are almost excluded from the margin of the orbit by the pre- and postfrontals. The postfrontal bones are sculpted, and the jugals are similarly adorned with longitudinal ridges. The parietal bones surround a small pineal foramen ("third eye"), a feature absent in most archosauriforms but sometimes found in the proterosuchid archosauriform Proterosuchus. The lower temporal fenestra is trapezoidal in shape, another characteristic previously on found in archosauriforms, while the upper temporal fenestrae are slender.[1]

A unique feature (autapomorphy) of Teyujagua is that the external mandibular fenestra is positioned unusually far forward on the lower jaw, directly beneath the eyes when the jaw is closed. The dentition is heterodont, bearing four small premaxillary teeth and a maximum of 15 larger maxillary teeth. The dentary tooth row is slightly shorter than the tooth row of the maxilla. The teeth are all laterally compressed and serrated, however unlike later Archosauriformes they are only serrated on their distal (rear) margins. The teeth are also unlike early archosauriform teeth in that they are loosely implanted in deep sockets (thecodont), whereas the earliest archosauriforms had teeth fused to their bony sockets (ankylothecodont).[1]

Discovery and Naming

The holotype material, UNIPAMPA 653, was collected from an exposure in the Sanga do Cabral Formation in Southern Brazil, informally known as Bica São Tomé, located in the Paraná Basin. The locality is composed of five outcrops, with UNIPAMPA 653 being found roughly 5 metres (16 ft) above the base of outcrop 5, in a layer rich in calcareous concretions. The specimen was collected by a team from the Paleobiology Laboratory of the Universidade Federal do Pampa (Unipampa) at the beginning of 2015,[2] and later described in a study co-authored by Dr. Felipe L. Pinheiro and others and published in Scientific Reports (Nature Publishing Group) in early 2016.[1]

The skull was noted to be exceptionally well preserved, as many other fossils from the Sanga do Cabral Formation are typically more fragmented and poorly preserved, having been reworked from slightly older sediments amongst layers of conglomerates.[1][3] In addition to its unusual completeness, the skull was also CT scanned to reveal further details of the fossil that were still hidden by the surrounding matrix, particularly areas of the left side of the skull, palatal and occipital regions.[1]

The genus name Teyujagua is derived from Teyú Yaguá, one of seven legendary monsters that are a part of Guaraní mythology. The Guaraní people occupied a large territory in central east South America, including an area of Southern Brazil where the type locality of Teyujagua is located. Teyú Yaguá is often depicted as a huge lizard with either seven or one large dog-head.[2] Pinheiro et al. named it for Teyú Yaguá with the intended literal translation of "fierce lizard", although "dog lizard" has been offered as the correct literal Guaraní translation.[4] The specific name is derived from Greek paradoxa ("paradoxical", "unexpected"), referring to its unusual combination of ancestral and derived archosauriform characteristics.[1]

Classification

In a phylogenetic analysis, Teyujagua was recovered as the sister taxon to Archosauriformes, in a more derived position than the Triassic Prolacerta. Pinheiro et al. performed the analysis using a novel data matrix assembled from two previous studies by Martin D. Ezcurra. Their analysis recovered two most parsimonious trees, both recovering a clade made up of Teyujagua and Archosauriformes. This clade is supported by five synapomorphies. The results of their analysis are reproduced and simplified below.

| Archosauromorpha |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

They also performed another analysis that included the enigmatic and poorly known Permian Eorasaurus, thought to be the oldest known archosauriform. The inclusion of Eorasaurus produced a broadly similar topology to the first analysis, with Teyujagua still occupying a sister position with Archosauriformes. However, it recovered Eorasaurus in an unresolved polytomy with Koilamasuchus, Fugusuchus, erythrosuchids and a clade composed of Euparkeriidae, Proterochampsia and Archosauria. This provides further support of archosauriform affinities for Eorasaurus, and so also supports the presence of archosauriform and archosauromorph ghost lineages extending back into the Permian period, at least into the middle Wuchiapingian of the late Permian.[1][5][6] Under these results, Teyujagua would represent a relict taxon that survived the end-Permian extinction from a prior evolutionary history in the late Permian.[1][3]

Evolutionary significance

Teyujagua provides a form of transitional morphology between Archosauriformes and other earlier archosauromorphs. Features previously considered unique to Archosauriformes, including the external mandibular fenestra and serrated teeth, are found in Teyujagua, and demonstrate that the key traits of Archosauriformes were acquired in a mosaic fashion, rather than evolving all at once. Furthermore, these features broadly relate to dietary adaptations, suggesting that archosauriform skulls were first being adapted for a predatory, hypercarnivorous lifestyle prior to the acquisition of features relating to pneumaticity (e.g. the antorbital fenestra and a closed temporal bar) that characterise later Archosauriformes.[1]

Teyujagua also supports a two-phase radiation model of archosauriform evolution at the end of the Permian and into the Triassic. The first of these radiations occurred as a phylogenetic diversification during the Lopingian, possibly as a response to the end-Guadalupian extinction event, where archosauriforms evolved as disaster taxa to fill minor predatory roles in Permian ecosystems, alongside their archosauromorph relatives. The second radiation follows the end-Permian extinction, where archosauriforms increased in size, abundance and species richness, coming to occupy the dominant terrestrial roles in Triassic ecosystems. The presence of the archosauriform Eorasaurus and proterosuchid Archosaurus in the Late Permian supports the initial diversification model,[5] and Teyujagua provides unique insight to the initial acquisition of traits in their early evolution in the Permian, as the skeletal records for Permian archosauriforms are rare and fragmentary.[1][6]

Palaeoecology

The Sanga do Cabral Formation is interpreted as representing a broad, semiarid plain with localised shallow braided stream channels. The most common vertebrate fauna are the procolophonoid parareptiles, particularly the genus Procolophon, as well as the fragmentary remains of temnospondyl amphibians, including the rhytidosteid Sangaia and the capitosauroid Tomeia.[7] Less common are the postcranial remains of other archosauromorphs, and possibly synapsids. The formation is roughly coeval with the Lystrosaurus Assemblage Zone in Karoo, South Africa, and shares a similar composition of Early Triassic fauna.[3]

Teyujagua may have been a semi-aquatic ambush predator along the margins of lakes and streams, as suggested by the dorsally positioned nares, similar to some later Crocodyliformes.[2] The serrated teeth and external mandibular fenestra imply the development of a hypercarnivorous lifestyle as in later Archosauriformes,[1] although the limited binocular vision suggests it was a visually oriented terrestrial predator.[8]

References

- Pinheiro, Felipe L.; França, Marco A. G.; Lacerda, Marcel B.; Butler, Richard J.; Schultz, Cesar L. (2016). "An exceptional fossil skull from South America and the origins of the archosauriform radiation". Scientific Reports. 6: 22817. Bibcode:2016NatSR...622817P. doi:10.1038/srep22817. PMC 4786805. PMID 26965521.

- "Palaeontologists discover 250 million year old new species of reptile in Brazil". University of Birmingham. March 11, 2016.

- Dias-da-Silva, Sérgio; Pinheiro, Felipe L.; Da-Rosa, Átila Augusto Stock; Martinelli, Agustín G.; Schultz, Cesar L.; Silva-Neves, Eduardo; Modesto, Sean P. (2017). "Biostratigraphic reappraisal of the Lower Triassic Sanga do Cabral Supersequence from South America, with a description of new material attributable to the parareptile genus Procolophon". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 79 (7): 281–296. Bibcode:2017JSAES..79..281D. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2017.07.012.

- Ortiz, Alberto Rodrigo Molinas (March 13, 2016). "Re: An exceptional fossil skull from South America and the origins of the archosauriform radiation". Scientific Reports. 6: 22817. Bibcode:2016NatSR...622817P. doi:10.1038/srep22817. PMC 4786805. PMID 26965521.

- Ezcurra, M. N. D.; Scheyer, T. M.; Butler, R. J. (2014). "The Origin and Early Evolution of Sauria: Reassessing the Permian Saurian Fossil Record and the Timing of the Crocodile-Lizard Divergence". PLoS ONE. 9 (2): e89165. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...989165E. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089165. PMC 3937355. PMID 24586565.

- Massimo Bernardi; Hendrik Klein; Fabio Massimo Petti; Martín D. Ezcurra (2015). "The origin and early radiation of archosauriforms: integrating the skeletal and footprint record". PLoS ONE. 10 (6): e0128449. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1028449B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0128449. PMC 4471049. PMID 26083612.

- Eltink, Estevan; Da-Rosa, Átila A Stock; Dias-da-Silva, Sérgio (2016). "A capitosauroid from the Lower Triassic of South America (Sanga do Cabral Supersequence: Paraná Basin), its phylogenetic relationships and biostratigraphic implications". Historical Biology. 29 (7): 863–874. doi:10.1080/08912963.2016.1255736.

- Oliveira, Daniel de Simão; Pinheiro, Felipe L. (2016). "O arcossauromorfo Teyujagua paradoxa possuía visão binocular?" (PDF). Boletim de Resumos. X Simpósio Brasileiro de Paleontologia de Vertebrados. 10. Rio de Janeiro. p. 121.

External links

- Brian Switek: Teyú Yaguá, in: National Geographic: Paleo Profile (25 March 2016)