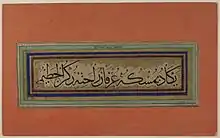

Thuluth

Thuluth (Arabic: ثُلُث, Ṯuluṯ or Arabic: خَطُّ الثُّلُث, Ḵaṭṭ-uṯ-Ṯuluṯ; Persian: ثلث, Sols; Turkish: Sülüs, from thuluth "one-third") is a script variety of Islamic calligraphy invented by Ibn Muqlah Shirazi.[1] The straight angular forms of Kufic were replaced in the new script by curved and oblique lines. In Thuluth, one-third of each letter slopes, from which the name (meaning "a third" in Arabic) comes. An alternative theory to the meaning is that the smallest width of the letter is one third of the widest part. It is an elegant, cursive script, used in medieval times on mosque decorations. Various calligraphic styles evolved from Thuluth through slight changes of form.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Islamic culture |

|---|

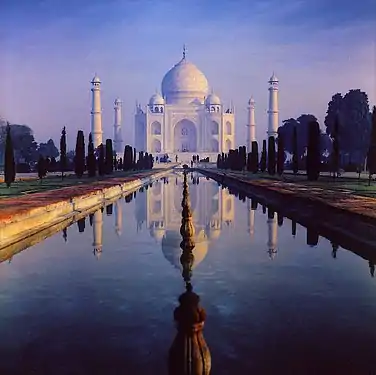

| Architecture |

| Art |

| Clothing |

| Holidays |

| Literature |

| Music |

| Theatre |

|

History

The greatest contributions to the evolution of the Thuluth script occurred in the Ottoman Empire in three successive steps that Ottoman art historians call "calligraphical revolutions":

- The first revolution occurred in the 15th century and was initiated by the master calligrapher Sheikh Hamdullah.[2][3]

- The second revolution resulted from the work of the Ottoman calligrapher Hâfız Osman in the 17th century.[4][5]

- Finally, in the late 19th century, Mehmed Şevkî Efendi gave the script the distinctive shape it has today.[6][7][8]

Artists

The best known artist to write the Thuluth script at its zenith is said to be Mustafa Râkım Efendi (1757–1826), a painter who set a standard in Ottoman calligraphy which many believe has not been surpassed to this day.[9]

_-_Google_Art_Project.jpg.webp)

Usage

Thuluth was used to write the headings of surahs, Qur'anic chapters. Some of the oldest copies of the Qur'an were written in Thuluth. Later copies were written in a combination of Thuluth and either Naskh or Muhaqqaq. After the 15th century Naskh came to be used exclusively.

The script is used in the Flag of Saudi Arabia where its text, Shahada al Tawhid, is written in Thuluth.

Style

An important aspect of Thuluth script is the use of harakat ("hareke" in Turkish) to represent vowel sounds and of certain other stylistic marks to beautify the script. The rules governing the former are similar to the rules for any Arabic script. The stylistic marks have their own rules regarding placement and grouping which allow for great creativity as to shape and orientation. For example, one grouping technique is to separate the marks written below letters from those written above.

Scripts developed from Thuluth

Since its creation, Thuluth has given rise to a variety of scripts used in calligraphy and over time has allowed numerous modifications. Jeli Thuluth was developed for use in large panels, such as those on tombstones. Muhaqqaq script was developed by widening the horizontal sections of the letters in Thuluth. Naskh script introduced a number of modifications resulting in smaller size and greater delicacy. Tawqi is a smaller version of Thuluth.

Ruq'ah was probably derived from the Thuluth and Naskh styles, the latter itself having originated from Thuluth.

See also

- Ibn Muqlah

- Islamic calligraphy

- Mohammad Hosni

References

- "Arabic Fonts - Development of the Thuluth Script". Retrieved 2019-02-07.

- "Hüseyin Kutlu: Hat sanatı kalemi şevk edebilmektir - Kalem Güzeli". www.kalemguzeli.net. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Pritchett, Frances. "hamdullah1500s". www.columbia.edu. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Üniversitesi, İstanbul. "İstanbul Üniversitesi - Tarihten Geleceğe Bilim Köprüsü - 145". www.istanbul.edu.tr. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Ali, Wijdan. "From the Literal to the Spiritual: The Development of Prophet Muhammad's Portrayal from 13th Century Ilkhanid Miniatures to 17th Century Ottoman Art Archived 2004-12-03 at the Wayback Machine". In Proceedings of the 11th International Congress of Turkish Art, eds. M. Kiel, N. Landman, and H. Theunissen. No. 7, 1–24. Utrecht, The Netherlands, August 23–28, 1999, p. 7

- "Mehmed Şevki Efendi". wordpress.com. 1 October 2006. Retrieved 17 April 2018.

- Türk Ýslam Sanatlarý - Tezyini Sanatlar Archived 2012-06-30 at Archive.today

- Journal of Ottoman Calligraphy :: RAKIM: “Mustafa Rakim” (1757 - 1826) :: April :: 2006 Archived 2008-03-06 at the Wayback Machine

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thuluth style. |

- Thuluth Script

- "Qur'anic Verses (56:77-9) on Carpet Page", dates back to the 14th century and utilizes Thuluth script, from the World Digital Library